INTRODUCTION

In developed countries, many food processing companies and farms employ unskilled foreign laborers, whose wages are lower than domestic laborers. Japan is not an exception. However, unlike other developed countries in Europe, North America, and Australasia, it is often the case that Japanese companies and farms employ unskilled foreign laborers under the pretense of “training.” This is because the Japanese government holds an official position that unskilled foreign laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan. This paper aims to outline the legal framework of Japan’s training program and discuss problems with its application to unskilled foreign laborers.

Japanese government’s dilemma regarding foreign laborers

In Japan, there are heated debates as to whether the country should accept unskilled foreign laborers. There are strong demands for unskilled foreign laborers in so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) workplaces, such as garment factories, food processing factories, and farms. This is because the Japanese laborers’ lifestyle is now so urbanized that they have a trend toward avoiding manual labor.

Simultaneously, however, quite a few Japanese citizens show their strong wariness toward unskilled foreign laborers. In public polls, Japanese responders often express their strong concern that unskilled foreign laborers deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the social order of Japanese communities1.

Thus, the Japanese government is in a dilemma of relieving citizens’ anxiety on the negative sides of foreign laborers by imposing strict regulation on unskilled foreign laborers or mitigating the labor shortage by accepting unskilled foreign laborers.

Gap between Japanese government’s official position and actual policy on unskilled foreign laborers

The Japanese government takes a crafty approach to the above-mentioned dilemma. In particular, the government makes a distinction between its official view and its actual policy. As described below, while the government repeatedly shows a negative attitude toward accepting unskilled foreign laborers in its official announcements, in actuality, the government does not close loopholes through which domestic companies receive unskilled foreign laborers.

The Japanese government often refers to the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” (a 1999 Cabinet decision) as its official position on how Japan should accept foreign laborers. This plan classifies foreign laborers into two types: skilled and unskilled. Considering that skilled foreign laborers are useful human resources for Japanese society, the government is positive about accepting them, but it shows a negative view of accepting unskilled foreign laborers.

However, the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” does not reflect the government’s actual policy on unskilled foreign laborers. For example, as described below, the government does not prevent Japanese companies and farms from accepting unskilled foreign laborers under the pretext of “training” 2.

Types of training programs for foreigners

There are two types of training programs for foreigners: (i) Training Program (TP) and (ii) Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). A foreign laborer in TP and TITP are called a trainee and a technical intern trainee, respectively.

The following four sections discuss the legal frameworks and problems of TP and TITP.

Legal framework of TP

A person who wants to stay in Japan as a trainee needs to receive the status of “trainee” from the Japanese Ministry of Justice (MOJ). To do so, he/she needs to register as a regular member of a sending organization in his/her country. Then, he/she must submit a training plan to the MOJ. If the plan is approved, the MOJ gives the status of “trainee” to him/her. After entering Japan, he/she at first goes to a primary accepting organization for classroom learning. Then, he/she goes to a secondary accepting organization for practical training.

By registering itself as a secondary accepting organization, a Japanese company or a farm receives (an) unskilled laborer(s) in the name of a trainee(s). In the case of agricultural foreign laborers, a popular pattern is that an agricultural cooperative registers itself as a primary accepting organization and its member farmers register themselves as secondary accepting organizations.

Note that the Japanese government does not admit a labor-management relation between a trainee and a secondary accepting organization because the nature of TP is “training” (not earning money by working in jobs). Accordingly, the payment for a trainee’s work is determined as “compensation” for necessary expenses for his/her stay in Japan instead of “salary.” Therefore, the Labor Standards Act is not applicable to trainees in TP.

To receive an approval from the MOJ, a TP plan should satisfy the following requirements as stipulated in Ordinance No. 16 of the MOJ:

(1) Requirements for a sending organization

A sending organization must be one of the following three types:

(1-i) An affiliation to the government or the public sector;

(1-ii) A joint corporation or a local subsidiary of a primary accepting organization; and

(1-iii) An institution that has a partnership with a primary accepting organization for more than one year or has produced transaction of more than 1 billion yen with a primary accepting organization in the most recent year;

(2) Requirements for an accepting organization

An accepting organization must satisfy all of the following five conditions (for either case of a primary accepting organization or a secondary one):

(2-i) The accepting organization must provide lodging and training facilities for the trainee(s);

(2-ii) The number of trainees accepted by the accepting organization must be less than one-twentieth (1/20th) of the total number of full-time workers in the accepting organization3;

(2-iii) The accepting organization must have an adviser to assist trainees with living in Japan;

(2-iv) The accepting organization must provide measures to cope with the death, accident, or sickness of trainees during the training, such as private insurance or other means (except for industrial accident compensation insurance); and

(2-v) Safety and sanitation measures with respect to the training facilities must be secured as provided for by the Labor Safety and Sanitation Act.

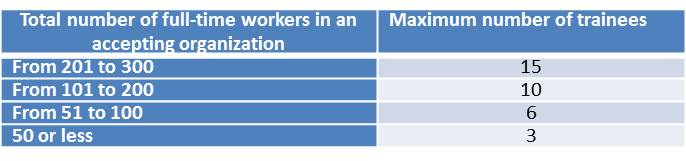

There is a special treatment on the regulation of the maximum number of trainees if the practical training is done under the supervision of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, an association of commerce and industry; an association of small businesses; or a vocational training corporation; and receives financial support from the public sector. Specifically, Table 1 is applied for the secondary accepting organization instead of (2-ii).

Table 1. Maximum number of trainees in accepting organization

(In case the training is arranged by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, an association of commerce and industry; a small business association; or a vocational training corporation)

(3) Requirements for a person listed for a trainee

A person listed for a trainee must satisfy all the following three conditions:

(3-i) The techniques, skills, and knowledge that he/she plans to acquire in Japan are not attainable thorough simple repeated practice;

(3-ii) He/she is 18 years old or older and is expected to return to his/her country after completing TP and perform jobs for which he/she receives training in TIP; and

(3-iii) The techniques, skills, and knowledge that he/she plans to acquire in Japan are difficult to attain in his/her country.

(4) Regulations on the duration for practical training

As mentioned earlier, the TP consists of two parts: (i) classroom learning at a primary accepting organization, and (ii) practical training at a secondary accepting organization. The Ordinance No. 16 of the MOJ requires, in principle, that the duration for practical training should be less than two-thirds of the total period of TP. However, if both the following two conditions are satisfied, the duration can be increased to four-fifths (4/5) of the total period of TP4.;

(i) The duration for practical training is four months or longer; and

(ii) Within the previous six months, an applicant has received over-160-hour-long classroom learning related to the training he/she is planning to receive in Japan.

Problems of TP

Apparently, the above-mentioned requirements present difficult hurdles for Japanese companies and farms to use TP. However, note that these requirements have some ambiguous content, and there is a room for arbitrary application of No. 16 Ordinance of the MOJ. For example, in applying (3-i), it depends on an observer’s viewpoint whether or not a job is regarded as “simple repeated practice.” Indeed, Fu (2011) argues that TP and below-mentioned TITP have been used in the way that accepting organizations want, which shows a strong demand for cheap foreign laborers.

In practice, a serious problem is that many of the trainees are in a significantly disadvantageous position. Oftentimes, a sending organization collects a large amount of money as a deposit from a person who wants to go to Japan as a trainee. In that case, the deposit will not be returned to the trainee unless he/she completes all the jobs (including jobs in TITP as described later) in Japan without any problem. In that sense, a Japanese company or a farm is in a stronger position than a trainee is. Indeed, it is alleged that trainees are often forced to do difficult jobs under tougher working conditions than what are written in the original training plans submitted to the MOJ. If such inappropriate practices become public, the training program will be canceled and the trainee will be required to return to his/her country without finishing all the scheduled jobs. Fearing that the sending organization will not return the deposit to him/her, a trainee keeps quiet even if he/she is treated badly in his/her workplace. Thus, it is alleged that trainees’ human rights are not protected. Such a problem has received great attention among human rights organizations both inside and outside Japan. For example, in the 94th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council that took place at Geneva in October 2008, Japan encountered severe criticisms for failure to protect human rights of TP trainees.

Legal framework of TITP

The length of the staying period for TP is limited to one year or less. However, when the remaining period of TP becomes one-sixth (1/6) of the entire period, by upgrading his/her status from a trainee in TP to a technical intern trainee in TITP, an unskilled foreign laborer is allowed to extend his/her staying period for another two years.

Ordinance No. 141 of the MOJ stipulates requirements for this upgrading as follows:

- The accepting organization must attest that the trainee has already acquired technical skills that are equivalent with the Basic 2-Level in the National Technical Skill Test;

- The trainee’s living conditions and working performance in TP are satisfactory; and

- The accepting organization that is responsible for his/her TP training has an appropriate plan for his/her TITP training

As is the case of Ordinance No. 16 of the MOJ, these requirements include some ambiguous points. For example, the meanings of “equivalent” in (i), “satisfactory” in (ii), and “appropriate” in (iii). In practice, Ordinance No. 141 of the MOJ is applied so flexibly that the upgrading from TP to TITP is not difficult. Usually, whether a trainee will continue receiving “training” as a technical intern trainee for another two years after completing one-year “training” is already determined in an unofficial procedure when he/she has a registration with a sending organization (i.e., before he/she comes to Japan).

Problems of TITP

The official explanation of the Japanese government is that the purpose of TP is the acquisition of basic knowledge and skills though “learning,” while that of TITP is the acquisition of practical skills through “laboring.” Accordingly, unlike the case of a trainee in TP, the relationship between a Japanese company or a farm and a technical intern trainee in TITP is officially recognized as labor relationships. Thus, the payment from a Japanese company or a farm to a technical intern trainee in TITP is salary (instead of compensation money for living expenses to a TP trainee). In addition, in theory, various regulations of the Labor Basic Act, such as maximum hours of overtime work and minimum wage, are imposed to protect workers’ rights.

In practice, however, technical intern trainees in TITP are often in a weak position for the same reason as the case of TP trainees. Thus, many human rights organizations (e.g., Japan Federation of Bar Associations [JFBA]) criticize not only TP but also TITP for the lack of workers’ rights protection5.

Complaints from Japanese companies and farms

The complaints on TP and TITP have been growing among Japanese companies and farms too. They find that some stipulations of TP and TITP are far from realistic. They request for deregulation in the following four points 6:

- The length of staying period should be extended;

It can take nearly a couple years to get accustomed to all the operations in a factory or a farm. However, in TP and TITP, the staying period of a foreign laborer is limited to three years or less. Therefore, it can happen that a foreign laborer returns to his/her country before adding power to the workplace.

- The regulation on types and places of operations should be relaxed.

A Japanese company or farm must list the types and places of operations before the TP or TITP starts. However, in practice, it can happen that the types and places of operations change according to changes in business conditions.

- The maximum number of trainees or technical intern trainees.

Labor shortage is very serious in 3D workplaces. In such workplaces, Japanese companies and farms find that the maximum number of trainees (shown in above-mentioned Table 1 and condition [2-ii]) is too restrictive.

- Classroom lesson may not be necessary.

Since trainees are de facto unskilled laborers, Japanese companies and farms prefer letting trainees to spend more time in factories and farms instead of classrooms.

Revision of TP and TITP in 2010

As a response to criticisms of the United Nations Human Rights Committee and others, the Japanese government revised the TP and TITP frameworks in July 2010. The essence of this revision is shown in Table 2. As can be seen, the government expanded the scope of TITP and divided TITP into two types: TITP Type 1 for the first year of TITP and TITP Type 2 for the second and third years of TITP. By this revision, unskilled foreign laborers are allowed to work as technical intern trainees in TITP (instead of trainees in TP) from the first year of their stay in Japan. Accordingly, the relationship between a Japanese company or a farm and an unskilled foreign laborer is recognized as labor relationships throughout his/her stay in Japan6.

Table 2. Statuses and programs for unskilled foreign laborers

However, the impacts of this revision are unclear because TITP trainees’ position remains weak, as discussed in Section 8. The JFBA (2013) asserts that this revision can be seen as a time serving remedy to the criticisms and produces no significant improvement for unskilled foreign laborers’ position. Studying 203 cases of violation of workers’ rights in TITP between July 2010 and June 2013, the JFBA (2013) concludes that the revision in 2010 is not effective in improving the living and working conditions of unskilled foreign laborers in Japan. The United States Department of State (2012) presents a similar view on this point with the JFBA (2013).

Total number of trainees and technical intern trainees and its breakdown by job types and country

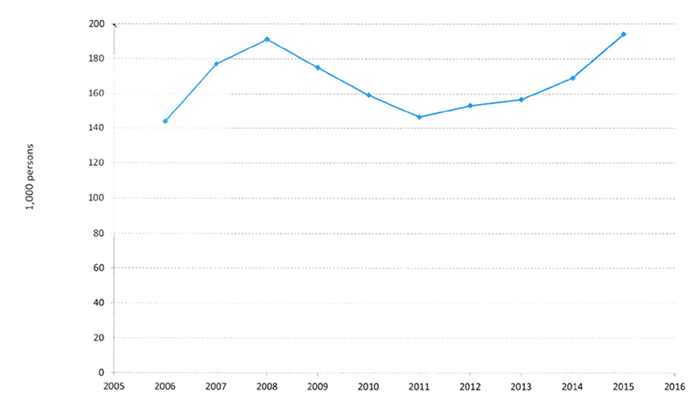

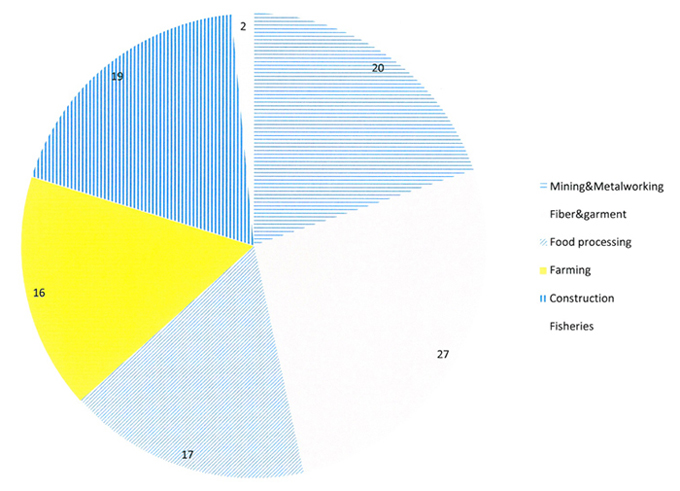

Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 show the total number of trainees and technical intern trainees for 2006-2015 and its breakdown by job types. The total number of trainees and technical intern trainees once declined from 2008 to 2011. There are two reasons for this decline. First, due to heavy damages from the global financial crisis, Japan’s labor demand shrank during these four years. Second, worrying that Japanese authorities such as the MOJ would become more serious in protecting workers’ rights, Japanese companies and farms were in a wait-and-see mode.

However, since 2012, the total number of trainees and technical intern trainees has been increasing. In particular, the agricultural and food industries have been increasing its demand for unskilled foreign workers since 2011.

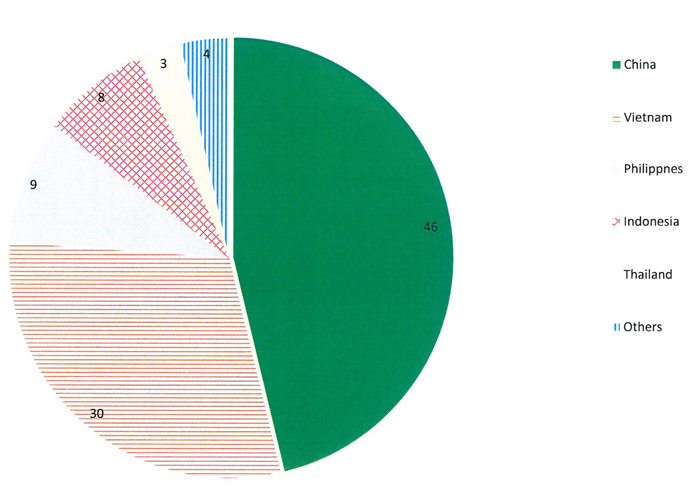

Fig. 3 shows the percentage composition of the total number of technical intern trainees by country. As can be seen, China and Viet Nam account for nearly three-fourths of the total.

Fig. 1. Total number of trainees and technical intern trainees.

Source: Ministry of Justice

Fig. 2. Percentage composition of trainees and technical intern trainees by job type (for 2015).

Source: Ministry of Justice.

Fig. 3. Percentage composition of trainees and technical intern trainees by country (for 2015).

Source: Ministry of Justice.

CONCLUSION

The Japanese government often refers to the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” as its official view on how Japan should accept foreign laborers. This plan classifies foreign laborers into two types: skilled and unskilled. Considering that foreign skilled laborers are useful human resources for Japanese society, the government is positive about accepting them. However, it shows a negative attitude toward accepting unskilled foreign laborers. This reflects the Japanese citizens’ strong anxiety that unskilled foreign laborers would deprive job opportunities of Japanese laborers and disturb their social order.

However, the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” does not reflect the government’s actual policy on unskilled foreign laborers. In fact, the government does not prevent Japanese companies and farms from employing unskilled foreign workers under the pretext of “training.” This is because the labor shortage in 3D workplaces is deepening.

Employing de facto unskilled foreign laborers in the pretext of “training” is creating various problems. Japanese employers complain on the inflexibility of the legal framework of the current “training” system. Moreover, human rights organizations point out that human rights of “trainees” are not protected adequately.

Criticisms toward Japan’s training system for foreigners have been growing both inside and outside of Japan. As a response to these criticisms, the Japanese government revised the training system in 2010. However, the JFBA (2013) asserts that this revision is a time serving remedy to the criticisms and has produced no significant change in the “training” system.

Currently, nearly 20,000 unskilled foreign laborers are staying in Japan, claiming that they are not laborers but “trainees.” Almost one-third (1/3) of them are working in food processing companies and farms. Considering the changing lifestyle and working ethics of Japanese laborers, it seems inevitable for Japan to increase its reliance on foreign laborers henceforth.

It seems necessary for the Japanese government to have an overall revision of its policy on unskilled foreign laborers. There are many views on this problem. Among them, a proposal of the JFBA (2013) presents an important basis for discussion. The JFBA (2013) asserts that the government should abandon the negative view of accepting unskilled foreign laborers, and officially open the Japanese labor market to developing countries by establishing a formal framework for receiving unskilled laborers.

FOOTNOTES

- For example, see a public poll on foreign laborers, which is conducted by the Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, in July 2010 (downloadable at http://survey.gov-online.go.jp/h12/gaikoku/2-3.html ).

- In addition to “trainees,” foreigner families who have Japanese parents or grandparents (e.g., descendants of immigrants from Japan to foreign countries) are allowed to stay in Japan as unskilled laborers for a certain period.

- There is a special treatment for farmers in applying this requirement. That is, if a farmer registers itself as a secondary accepting organization, the total number of trainees must be two or less.

- If a training program satisfies only one of conditions (i) and (ii), the duration for practical training can be increased to three-fourths of the total TP period.

- For example, see JFBA (2013).

- For example, see “Imin Shakai No Hajimari Ka” (Immigrants in Japan), Hakkyoku Tokuban (Documentary Series Made by a Team of the Eight Broadcast Companies in the Mainichi Broadcasting System), Mainichi Broadcasting System, May 5, 2008, Television.

- While the TP framework was not abolished in this revision, the MOJ changed its policy on application of TP. Particularly, since July 2010, TP has been used only for limited cases of providing “training” to foreigners in its original meaning (not for the purpose of receiving unskilled foreign laborers).

REFERENCES

Fu, Keiei, 2011, ‘Nihon Ni Okeru Gaikokujin Kenshusei Gino Jisshusei Seido Ni Kansuru Kenkyu’ (Foreign Trainees and Technical Intern Trainees in Japan), Nihon No Gaikokujin Ryugakusei Rodosha To Koyo Mondai (Foreign Students and Laborers and their Labor Problems in Japan), (ed.) Takashi Moriya, Kosho Shobo.

Japan Federation of Bar Association (JFBA), 2013, ‘Gaikokujin Gino Seido No Sokyu No Haishi Wo Motomeru Ikensho’ (A Proposal to Abolish Technical Intern Training Program).

United States Department of State, 2012, Trafficking in Persons Report 2012.

|

Date submitted: Aug. 1, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Aug. 3, 2016

|

Unskilled Foreign Laborers in Japanese Food Processing Companies and Farms Under the Pretense of Training

INTRODUCTION

In developed countries, many food processing companies and farms employ unskilled foreign laborers, whose wages are lower than domestic laborers. Japan is not an exception. However, unlike other developed countries in Europe, North America, and Australasia, it is often the case that Japanese companies and farms employ unskilled foreign laborers under the pretense of “training.” This is because the Japanese government holds an official position that unskilled foreign laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan. This paper aims to outline the legal framework of Japan’s training program and discuss problems with its application to unskilled foreign laborers.

Japanese government’s dilemma regarding foreign laborers

In Japan, there are heated debates as to whether the country should accept unskilled foreign laborers. There are strong demands for unskilled foreign laborers in so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) workplaces, such as garment factories, food processing factories, and farms. This is because the Japanese laborers’ lifestyle is now so urbanized that they have a trend toward avoiding manual labor.

Simultaneously, however, quite a few Japanese citizens show their strong wariness toward unskilled foreign laborers. In public polls, Japanese responders often express their strong concern that unskilled foreign laborers deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the social order of Japanese communities1.

Thus, the Japanese government is in a dilemma of relieving citizens’ anxiety on the negative sides of foreign laborers by imposing strict regulation on unskilled foreign laborers or mitigating the labor shortage by accepting unskilled foreign laborers.

Gap between Japanese government’s official position and actual policy on unskilled foreign laborers

The Japanese government takes a crafty approach to the above-mentioned dilemma. In particular, the government makes a distinction between its official view and its actual policy. As described below, while the government repeatedly shows a negative attitude toward accepting unskilled foreign laborers in its official announcements, in actuality, the government does not close loopholes through which domestic companies receive unskilled foreign laborers.

The Japanese government often refers to the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” (a 1999 Cabinet decision) as its official position on how Japan should accept foreign laborers. This plan classifies foreign laborers into two types: skilled and unskilled. Considering that skilled foreign laborers are useful human resources for Japanese society, the government is positive about accepting them, but it shows a negative view of accepting unskilled foreign laborers.

However, the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” does not reflect the government’s actual policy on unskilled foreign laborers. For example, as described below, the government does not prevent Japanese companies and farms from accepting unskilled foreign laborers under the pretext of “training” 2.

Types of training programs for foreigners

There are two types of training programs for foreigners: (i) Training Program (TP) and (ii) Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). A foreign laborer in TP and TITP are called a trainee and a technical intern trainee, respectively.

The following four sections discuss the legal frameworks and problems of TP and TITP.

Legal framework of TP

A person who wants to stay in Japan as a trainee needs to receive the status of “trainee” from the Japanese Ministry of Justice (MOJ). To do so, he/she needs to register as a regular member of a sending organization in his/her country. Then, he/she must submit a training plan to the MOJ. If the plan is approved, the MOJ gives the status of “trainee” to him/her. After entering Japan, he/she at first goes to a primary accepting organization for classroom learning. Then, he/she goes to a secondary accepting organization for practical training.

By registering itself as a secondary accepting organization, a Japanese company or a farm receives (an) unskilled laborer(s) in the name of a trainee(s). In the case of agricultural foreign laborers, a popular pattern is that an agricultural cooperative registers itself as a primary accepting organization and its member farmers register themselves as secondary accepting organizations.

Note that the Japanese government does not admit a labor-management relation between a trainee and a secondary accepting organization because the nature of TP is “training” (not earning money by working in jobs). Accordingly, the payment for a trainee’s work is determined as “compensation” for necessary expenses for his/her stay in Japan instead of “salary.” Therefore, the Labor Standards Act is not applicable to trainees in TP.

To receive an approval from the MOJ, a TP plan should satisfy the following requirements as stipulated in Ordinance No. 16 of the MOJ:

(1) Requirements for a sending organization

A sending organization must be one of the following three types:

(1-i) An affiliation to the government or the public sector;

(1-ii) A joint corporation or a local subsidiary of a primary accepting organization; and

(1-iii) An institution that has a partnership with a primary accepting organization for more than one year or has produced transaction of more than 1 billion yen with a primary accepting organization in the most recent year;

(2) Requirements for an accepting organization

An accepting organization must satisfy all of the following five conditions (for either case of a primary accepting organization or a secondary one):

(2-i) The accepting organization must provide lodging and training facilities for the trainee(s);

(2-ii) The number of trainees accepted by the accepting organization must be less than one-twentieth (1/20th) of the total number of full-time workers in the accepting organization3;

(2-iii) The accepting organization must have an adviser to assist trainees with living in Japan;

(2-iv) The accepting organization must provide measures to cope with the death, accident, or sickness of trainees during the training, such as private insurance or other means (except for industrial accident compensation insurance); and

(2-v) Safety and sanitation measures with respect to the training facilities must be secured as provided for by the Labor Safety and Sanitation Act.

There is a special treatment on the regulation of the maximum number of trainees if the practical training is done under the supervision of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, an association of commerce and industry; an association of small businesses; or a vocational training corporation; and receives financial support from the public sector. Specifically, Table 1 is applied for the secondary accepting organization instead of (2-ii).

Table 1. Maximum number of trainees in accepting organization

(In case the training is arranged by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, an association of commerce and industry; a small business association; or a vocational training corporation)

(3) Requirements for a person listed for a trainee

A person listed for a trainee must satisfy all the following three conditions:

(3-i) The techniques, skills, and knowledge that he/she plans to acquire in Japan are not attainable thorough simple repeated practice;

(3-ii) He/she is 18 years old or older and is expected to return to his/her country after completing TP and perform jobs for which he/she receives training in TIP; and

(3-iii) The techniques, skills, and knowledge that he/she plans to acquire in Japan are difficult to attain in his/her country.

(4) Regulations on the duration for practical training

As mentioned earlier, the TP consists of two parts: (i) classroom learning at a primary accepting organization, and (ii) practical training at a secondary accepting organization. The Ordinance No. 16 of the MOJ requires, in principle, that the duration for practical training should be less than two-thirds of the total period of TP. However, if both the following two conditions are satisfied, the duration can be increased to four-fifths (4/5) of the total period of TP4.;

(i) The duration for practical training is four months or longer; and

(ii) Within the previous six months, an applicant has received over-160-hour-long classroom learning related to the training he/she is planning to receive in Japan.

Problems of TP

Apparently, the above-mentioned requirements present difficult hurdles for Japanese companies and farms to use TP. However, note that these requirements have some ambiguous content, and there is a room for arbitrary application of No. 16 Ordinance of the MOJ. For example, in applying (3-i), it depends on an observer’s viewpoint whether or not a job is regarded as “simple repeated practice.” Indeed, Fu (2011) argues that TP and below-mentioned TITP have been used in the way that accepting organizations want, which shows a strong demand for cheap foreign laborers.

In practice, a serious problem is that many of the trainees are in a significantly disadvantageous position. Oftentimes, a sending organization collects a large amount of money as a deposit from a person who wants to go to Japan as a trainee. In that case, the deposit will not be returned to the trainee unless he/she completes all the jobs (including jobs in TITP as described later) in Japan without any problem. In that sense, a Japanese company or a farm is in a stronger position than a trainee is. Indeed, it is alleged that trainees are often forced to do difficult jobs under tougher working conditions than what are written in the original training plans submitted to the MOJ. If such inappropriate practices become public, the training program will be canceled and the trainee will be required to return to his/her country without finishing all the scheduled jobs. Fearing that the sending organization will not return the deposit to him/her, a trainee keeps quiet even if he/she is treated badly in his/her workplace. Thus, it is alleged that trainees’ human rights are not protected. Such a problem has received great attention among human rights organizations both inside and outside Japan. For example, in the 94th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council that took place at Geneva in October 2008, Japan encountered severe criticisms for failure to protect human rights of TP trainees.

Legal framework of TITP

The length of the staying period for TP is limited to one year or less. However, when the remaining period of TP becomes one-sixth (1/6) of the entire period, by upgrading his/her status from a trainee in TP to a technical intern trainee in TITP, an unskilled foreign laborer is allowed to extend his/her staying period for another two years.

Ordinance No. 141 of the MOJ stipulates requirements for this upgrading as follows:

As is the case of Ordinance No. 16 of the MOJ, these requirements include some ambiguous points. For example, the meanings of “equivalent” in (i), “satisfactory” in (ii), and “appropriate” in (iii). In practice, Ordinance No. 141 of the MOJ is applied so flexibly that the upgrading from TP to TITP is not difficult. Usually, whether a trainee will continue receiving “training” as a technical intern trainee for another two years after completing one-year “training” is already determined in an unofficial procedure when he/she has a registration with a sending organization (i.e., before he/she comes to Japan).

Problems of TITP

The official explanation of the Japanese government is that the purpose of TP is the acquisition of basic knowledge and skills though “learning,” while that of TITP is the acquisition of practical skills through “laboring.” Accordingly, unlike the case of a trainee in TP, the relationship between a Japanese company or a farm and a technical intern trainee in TITP is officially recognized as labor relationships. Thus, the payment from a Japanese company or a farm to a technical intern trainee in TITP is salary (instead of compensation money for living expenses to a TP trainee). In addition, in theory, various regulations of the Labor Basic Act, such as maximum hours of overtime work and minimum wage, are imposed to protect workers’ rights.

In practice, however, technical intern trainees in TITP are often in a weak position for the same reason as the case of TP trainees. Thus, many human rights organizations (e.g., Japan Federation of Bar Associations [JFBA]) criticize not only TP but also TITP for the lack of workers’ rights protection5.

Complaints from Japanese companies and farms

The complaints on TP and TITP have been growing among Japanese companies and farms too. They find that some stipulations of TP and TITP are far from realistic. They request for deregulation in the following four points 6:

It can take nearly a couple years to get accustomed to all the operations in a factory or a farm. However, in TP and TITP, the staying period of a foreign laborer is limited to three years or less. Therefore, it can happen that a foreign laborer returns to his/her country before adding power to the workplace.

A Japanese company or farm must list the types and places of operations before the TP or TITP starts. However, in practice, it can happen that the types and places of operations change according to changes in business conditions.

Labor shortage is very serious in 3D workplaces. In such workplaces, Japanese companies and farms find that the maximum number of trainees (shown in above-mentioned Table 1 and condition [2-ii]) is too restrictive.

Since trainees are de facto unskilled laborers, Japanese companies and farms prefer letting trainees to spend more time in factories and farms instead of classrooms.

Revision of TP and TITP in 2010

As a response to criticisms of the United Nations Human Rights Committee and others, the Japanese government revised the TP and TITP frameworks in July 2010. The essence of this revision is shown in Table 2. As can be seen, the government expanded the scope of TITP and divided TITP into two types: TITP Type 1 for the first year of TITP and TITP Type 2 for the second and third years of TITP. By this revision, unskilled foreign laborers are allowed to work as technical intern trainees in TITP (instead of trainees in TP) from the first year of their stay in Japan. Accordingly, the relationship between a Japanese company or a farm and an unskilled foreign laborer is recognized as labor relationships throughout his/her stay in Japan6.

Table 2. Statuses and programs for unskilled foreign laborers

However, the impacts of this revision are unclear because TITP trainees’ position remains weak, as discussed in Section 8. The JFBA (2013) asserts that this revision can be seen as a time serving remedy to the criticisms and produces no significant improvement for unskilled foreign laborers’ position. Studying 203 cases of violation of workers’ rights in TITP between July 2010 and June 2013, the JFBA (2013) concludes that the revision in 2010 is not effective in improving the living and working conditions of unskilled foreign laborers in Japan. The United States Department of State (2012) presents a similar view on this point with the JFBA (2013).

Total number of trainees and technical intern trainees and its breakdown by job types and country

Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 show the total number of trainees and technical intern trainees for 2006-2015 and its breakdown by job types. The total number of trainees and technical intern trainees once declined from 2008 to 2011. There are two reasons for this decline. First, due to heavy damages from the global financial crisis, Japan’s labor demand shrank during these four years. Second, worrying that Japanese authorities such as the MOJ would become more serious in protecting workers’ rights, Japanese companies and farms were in a wait-and-see mode.

However, since 2012, the total number of trainees and technical intern trainees has been increasing. In particular, the agricultural and food industries have been increasing its demand for unskilled foreign workers since 2011.

Fig. 3 shows the percentage composition of the total number of technical intern trainees by country. As can be seen, China and Viet Nam account for nearly three-fourths of the total.

Fig. 1. Total number of trainees and technical intern trainees.

Source: Ministry of Justice

Fig. 2. Percentage composition of trainees and technical intern trainees by job type (for 2015).

Source: Ministry of Justice.

Fig. 3. Percentage composition of trainees and technical intern trainees by country (for 2015).

Source: Ministry of Justice.

CONCLUSION

The Japanese government often refers to the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” as its official view on how Japan should accept foreign laborers. This plan classifies foreign laborers into two types: skilled and unskilled. Considering that foreign skilled laborers are useful human resources for Japanese society, the government is positive about accepting them. However, it shows a negative attitude toward accepting unskilled foreign laborers. This reflects the Japanese citizens’ strong anxiety that unskilled foreign laborers would deprive job opportunities of Japanese laborers and disturb their social order.

However, the “9th Basic Plan for Employment Measures” does not reflect the government’s actual policy on unskilled foreign laborers. In fact, the government does not prevent Japanese companies and farms from employing unskilled foreign workers under the pretext of “training.” This is because the labor shortage in 3D workplaces is deepening.

Employing de facto unskilled foreign laborers in the pretext of “training” is creating various problems. Japanese employers complain on the inflexibility of the legal framework of the current “training” system. Moreover, human rights organizations point out that human rights of “trainees” are not protected adequately.

Criticisms toward Japan’s training system for foreigners have been growing both inside and outside of Japan. As a response to these criticisms, the Japanese government revised the training system in 2010. However, the JFBA (2013) asserts that this revision is a time serving remedy to the criticisms and has produced no significant change in the “training” system.

Currently, nearly 20,000 unskilled foreign laborers are staying in Japan, claiming that they are not laborers but “trainees.” Almost one-third (1/3) of them are working in food processing companies and farms. Considering the changing lifestyle and working ethics of Japanese laborers, it seems inevitable for Japan to increase its reliance on foreign laborers henceforth.

It seems necessary for the Japanese government to have an overall revision of its policy on unskilled foreign laborers. There are many views on this problem. Among them, a proposal of the JFBA (2013) presents an important basis for discussion. The JFBA (2013) asserts that the government should abandon the negative view of accepting unskilled foreign laborers, and officially open the Japanese labor market to developing countries by establishing a formal framework for receiving unskilled laborers.

FOOTNOTES

REFERENCES

Fu, Keiei, 2011, ‘Nihon Ni Okeru Gaikokujin Kenshusei Gino Jisshusei Seido Ni Kansuru Kenkyu’ (Foreign Trainees and Technical Intern Trainees in Japan), Nihon No Gaikokujin Ryugakusei Rodosha To Koyo Mondai (Foreign Students and Laborers and their Labor Problems in Japan), (ed.) Takashi Moriya, Kosho Shobo.

Japan Federation of Bar Association (JFBA), 2013, ‘Gaikokujin Gino Seido No Sokyu No Haishi Wo Motomeru Ikensho’ (A Proposal to Abolish Technical Intern Training Program).

United States Department of State, 2012, Trafficking in Persons Report 2012.

Date submitted: Aug. 1, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Aug. 3, 2016