ABSTRACT

Agricultural cooperatives’ marketing business, especially on a pool basis, becomes more important as the agricultural market is increasingly globalized and concentrated by a few large-scale supermarkets. If agricultural cooperatives’ pooling is operated sufficiently in large, it would contribute to an efficiency-increase of the agricultural market through the ‘competitive yardstick’ role. Furthermore it would induce a reduction of marketing cost in all units of volume of the pooled products. Through the pooling’s effects, ultimately member-farmers would receive a higher price on raw products that they deliver. This paper introduces some successful pooling cases of agricultural cooperatives in Korea. Some factors, which include marketing agreements, quality management, fair pool-based payment, and education for farmers, are found to be important for successful pooling operations. Although a pooling program may be applied differently to agricultural cooperatives depending on each country, it can be an effective measure for member-farmers’ economic benefits, considering current market changes.

Key words: agricultural cooperative, pooling program, marketing efficiency

Introduction

Korea has experienced a significant transition in the agricultural market since the mid- 1990s. Since 1995, when the URAA (Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture) went into effect, the Korean agricultural market has been almost fully opened by converting import restrictions into tariffs. Furthermore, due to FTAs (Free Trade Agreements) with large countries in the agricultural industry, such as the USA and EU, import of agricultural products has significantly increased. From 1995 to 2014, imports of agricultural products increased by about 260% from $6.9 billion to $24.9 billion. Import of agricultural product is predicted to further increase as FTAs with many countries are implemented.

Moreover, the domestic agricultural marketing system has significantly changed in Korea. Since the early 2000’s, a few large supermarkets have rapidly grown in terms of retail-market share of agricultural products and their market power against farmers has been increasing. Thus, Korean farmers are now faced with the challenge of competing with foreign agricultural products while simultaneously coping with the increasing market power of the large-scale supermarkets. However, it is definitely not easy for farmers, particularly small-scale farmers, to do the tasks individually. Therefore, the role of agricultural cooperatives is becoming more important in the Korean agricultural market.

Agricultural cooperatives can contribute to an increase in member-farmers’ economic benefit by strengthening pooling operations. Pooling is a marketing practice specialized for cooperatives, which includes collecting, grading, packing, and distributing agricultural products as well as paying member-farmers on a group basis after selling their final products. By pooling, agricultural cooperatives can increase their bargaining power against large-scale buyers and reduce marketing costs throughout all stages from collection to final sale of the products. Therefore, pooling contributes to a higher price on raw products, so member-farmers receive increased returns.

It follows, then, that strengthening the cooperatives’ pooling system is one of the most important measures to effectively compete with imported agricultural products and cope with the increased buyers’ market power. Considering these points, Korean agricultural cooperatives have recently tried to establish more activated pooling organizations, which are operated by contracts or agreements between cooperatives and farmers. Furthermore, the agricultural cooperatives have pursued joint marketing among themselves in order to increase the pooling effects. As a result, a number of successful pooling cases have emerged and they are becoming good examples to other agricultural cooperatives in Korea.

The objective of this paper is to introduce some agricultural cooperatives’ pooling cases in Korea and derive implications for successful pooing operations. For this purpose, this paper first reviews some advantages of the cooperatives’ pooling operations, especially in terms of marketing efficiency, with brief theoretical concepts. It then overviews recent efforts of agricultural cooperatives to activate pooling operations and derives major factors for successful pooling operations through some useful cases. Then conclusions and implications are provided in the final section.

Some advantages of agricultural cooperatives’ pooling

The agricultural market, especially the vegetable and fruit markets, consists of a large number of small-scale farmers and a small number of large-scale buyers. This market condition is usually referred to as oligopsony in economics, and under such a condition, farmers are in a much weaker position than the buyers in terms of market power. Therefore, farmers usually receive a lower price in that market than they do in a competitive market. However, if farmers use a cooperative’s pooling system, they are expected to receive a higher price due to increased bargaining power by pooling.

If an agricultural cooperative constructs a strong pooling system in terms of volume and quality of raw product delivered by farmers, it would induce purchasing competition among the buyers and thereby contribute to farmers receiving higher prices. Ultimately, it would also contribute to an increase in efficiency of the agricultural market through making resource allocation more efficient. This is known as cooperative’s ‘competitive yardstick’ role. Another advantage of cooperative’s pooling operations is to improve efficiency of marketing-cost structure by both economies of scale and reduction of per-unit marketing cost. The cooperative’s pooling system allows farmers’ individual expenses related to activities after the harvest, such as grading, packing, and distribution, to spread out over a larger volume of raw product that they delivered to the cooperative.

The supply of raw product rises as the farmers participating in the cooperative’s pooling system grow in number. Figure 1 shows that the price of raw product goes up from r1 to r2 by economies of scale as the supply rises from S1 to S2.[1] Consider that the pooling of an agricultural cooperative is small scale. Then the cooperative faces an upward-sloping NARP (Net average revenue product) curve, or equivalently, a downward-sloping average processing cost curve. Hence, economies of scale are present in this case because the average processing cost falls as the quantity of raw product rises. Thus, making the pooling scale sufficiently large, through inducing more farmers’ participation, is an important task for the cooperative with a small pooling scale, as shown in Fig. 1.

Another possible choice for larger scale pooling is to build a joint marketing system among cooperatives. If this were feasible, per-unit marketing costs would be reduced in all units of volume of raw product that member-farmers deliver. Figure 2 shows that price of raw product goes up from r3 to r4 by reduction of per unit marketing cost in all units of volume. The NARP curve itself shifts upward as per unit marketing cost decreases in all units of volume. Thus, if the pooling scale is sufficiently large, farmers participating in the pooling system are expected to receive a higher price than before by both the increased supply and the shift upward of NARP in all units of volume as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1. Effects of cooperative’s pooling in terms of ‘economies of scale’

.jpg)

Fig. 2. Effects of cooperative’s pooling in terms of marketing-cost reduction

Cases of agricultural cooperatives’ pooling in Korea

Overview of pooling operations

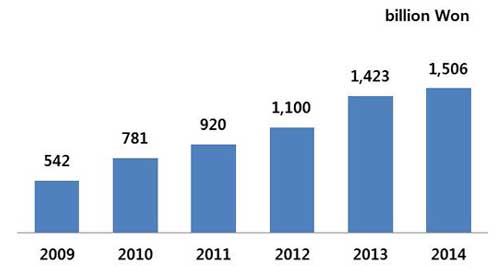

In general, member-farmers of the local agricultural cooperative have no obligation to deliver the raw products that they produce to their cooperatives. Thus, participation of member-farmers in the cooperative’s marketing business is not sufficient and usually their pooling scale is small. This is a structural problem in that cooperatives have difficulty sufficiently scaling marketing business. To overcome this problem, a number of local agricultural cooperatives have voluntarily established product-specific pooling organizations, which are operated by marketing agreements between the cooperatives and member-farmers, since the mid-2000s. Usually, a local agricultural cooperative operates the pooling organizations for more than one product. For example, a cooperative operates grape, peach, and potato pooling organizations separately. In 2014, there were about 1,900 pooling organizations in operation nationwide. Sales of the pooling organizations increased by 178% from 2009 to 2014 (Figure 3).

Korean agriculture is characterized by small-scale family farms. Per-farm household cultivation area is approximately 1.5ha on average. Because of this, a local cooperative can operate the pooling organization but it usually lacks marketing scaling large enough to have bargaining power against large-scale buyers. Hence, since the mid-2000s, some local agricultural cooperatives have tried to make the pooling scale be larger by pursuing joint marketing among the cooperatives. For this, they have established secondary marketing organizations by joint investments. Currently, about 50 secondary marketing organizations are being operated nationwide with marketing-specialized roles.

Fig. 3. Sales of pooling organizations in Korea during 2009~2014

Major factors in successful pooling cases

The agricultural cooperative needs to handle a sufficiently large volume with high-quality products in order to increase its marketing power against buyers. For this, the binding marketing contract or agreement between the cooperative and member-farmers is important in its marketing business. The agreement includes the rights, duties, and responsibilities of both parties relevant to the cooperative marketing.

The local agricultural cooperatives that operate the pooling organizations usually make the marketing agreement. In most cases, based on the agreement, farmers deliver all or part of their products to the cooperatives. Also, they cultivate a specific variety of a product and complete a study course for quality management. The cooperative, also according to the agreement, instructs members’ farming activities, such as variety choice, time control of sowing and harvesting, and cultivation techniques.

In general, the agreement sets a penalty, to be applied if farmers violate the rules, especially pertaining to volume of delivery and criteria of quality. In most cases, if a farmer does violate the rules, he is dismissed from the pooling organization directly or after a warning depending upon the marketing agreement. In the actual case of a local cooperative in 2011, about 60 percent of farmers who belonged to a grape pooling organization violated a delivery rule by selling their grape to other merchants. At that time, the organization held a general meeting and decided to disband itself. Then, the organization was newly established with the condition that if a farmer violates the rule even at one time, he is dismissed without any warning. Since then, the pooling organization has seen no violations of its rules.

Quality control of agricultural products is a key factor in stabilizing the cooperative’s marketing business. By providing good-quality products consistently with consideration of consumers’ preferences, the cooperative can enhance its marketing ability. If we look to a successful case, we can see that the pooling organization tries to manage quality of products throughout all pooling stages, from cultivation to delivery.

In the cultivation stage, the cooperative instructs farmers to unify a variety of a products, agricultural supplies, and cultivation techniques with expert consultation. After the harvest, the cooperative grades the farmers’ products following the selection standards including size, appearance, color, sugar content, etc. Grading is conducted in a marketing facility with functions of packing, storing, and distributing as well as grading. Any farmer is prohibited from being involved in the process of grading for fairness. After grading, the products that do not satisfy the selection standards are sold separately, being excluded from the pooled products. The following is an example of good quality management system.

Example: Quality management process of a local agricultural cooperative

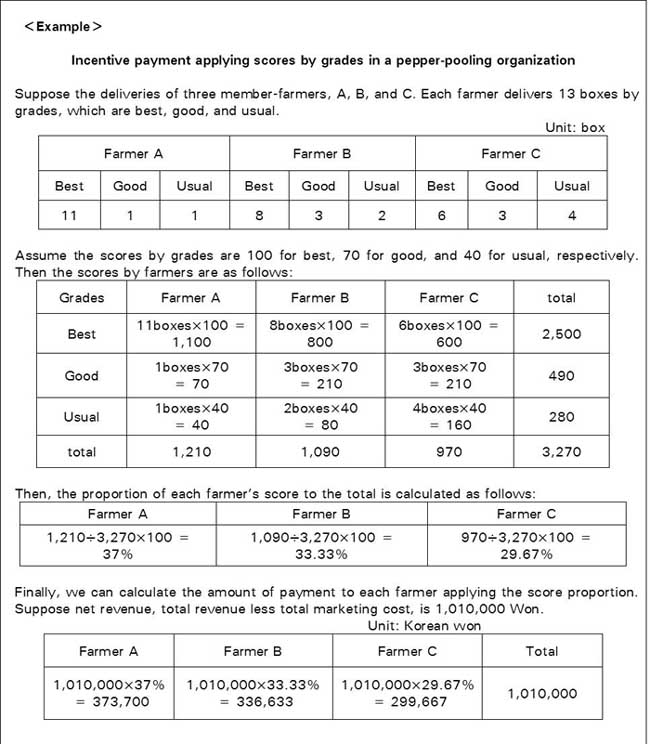

Fair payment after the sale of final products is a critical factor for the cooperative’s successful pooling operations. It prevents free-riders and increases the participation of better farmers in terms of product quality. If the same amount is paid to all member-farmers on the basis of average, regardless of quality, some farmers who delivered higher-quality products would make a loss and might secede from the pooling organization due to dissatisfaction with the payment.

The successful cooperatives in the pooling operations commonly emphasize fair payment. In many cases, an incentive is paid to farmers who delivered higher-quality products. This is of course facilitated by member-farmers’ consensus. The incentive-payment system would be useful for overall quality enhancement of raw products delivered by member-farmers, encouraging them to strive for quality management. The following is an example of the incentive-payment system of a local agricultural cooperative.

Member-farmers’ positive participation is important for the sustainable development of the cooperative’s pool marketing. The pooling effects, mentioned previously, can become greater if all member-farmers try to deliver high-quality products with a shared philosophy on pooling and a firm belief in cooperative’s pool marketing. Thus, the cooperative needs to operate an effective education system to pursue an increase in farmers’ understanding on pooling and thereby induce positive participation. An example of the education system is as follows:

Example: A six-step education system of a local agricultural cooperative

.jpg)

The price of agricultural products is usually inelastic with respect to supply and demand. Thus, even a little change in supply or demand can cause market prices of the products to fluctuate severely. Therefore, the agricultural cooperative needs to hedge against some unexpected changes, like a sharp fall in price, for its stable pool marketing. In some successful cases, the cooperative and member-farmers belonging to the pooling organization raise funds jointly in order to hedge against the risk like unexpected price-fall. The funds are also used for the purpose of joint activities, which are relevant to farming like pest control on a group basis, of the pooling organization. The cooperatives that operate the joint funding system usually raise amount by 0.5 or 1% of total sales. The joint funding is feasible only with consensus of member-farmers of the pooling organization.

Joint marketing among local agricultural cooperatives can increase market power and reduce marketing cost, thereby contributing greater economic benefit to member-farmers of each cooperative. Since the mid 2000s, some local agricultural cooperatives established secondary marketing organizations through joint investments, mostly on the county and city levels. In a successful case, systemization among the primary pooling organizations, the local cooperatives, and the secondary marketing organization is constructed with each having its role assignment as follows:

The member-farmers belonging to the pooling organizations deliver high-quality products to their local cooperatives according to marketing agreements. The local agricultural cooperatives provide member-farmers with support and education about cultivation technique, quality management, and other farming activities. Moreover, they jointly grade the delivered products in marketing facilities then consign the products to the secondary marketing organization that they invested in.

The secondary marketing organization is wholly responsible for marketing activities, including development of new buyers, sales strategies targeting each buyer, promotion of the joint brand, etc. Buyers generally include wholesale markets, large-scale supermarkets, food-processing companies, retail stores, etc. After finally selling the products, the secondary marketing organizations pay the joined local cooperatives on a pool basis. Then, each cooperative pays its member-farmers returns for the raw products they delivered. The following is a case of systemization among pooling organizations, local agricultural cooperatives, and their secondary marketing organization.

Example: A case of linkage among pooling organizations, local agricultural cooperatives, and secondary marketing organization

CONCLUSION

The main objective of agricultural cooperatives is to maximize member-farmers’ economic benefits. This can be achieved by providing member-farmers with greater returns on raw products through the cooperatives’ marketing business. Whether the objective can be achieved depends upon the extent of the cooperatives’ bargaining power against large-scale buyers, especially in an imperfect competition market. Thus, it is important that the cooperatives try to achieve a balance in market power with the buyers by establishing a large-scale pooling system. Pooling is a marketing activity distinct to cooperatives and generally includes collecting, grading, packing, storing, and selling agricultural products delivered by member-farmers then distributing payment on a group basis after selling the final products.

Agricultural cooperatives can increase their bargaining power with a sufficiently large pooling system and thereby induce the buyers’ purchasing competition. This makes the agricultural market more efficient, which is known as cooperative’s ‘competitive-yardstick’ role. Through this role, the cooperatives ultimately provide member-farmers with more returns on the raw products they delivered. The pooling system can also lead to a reduction of marketing costs in each volume unit of the products by spreading out the cost over the collected products, which also contributes to providing member-farmers with greater returns.

However, effectively operating a stable pooling system is more important than simply constructing the system. To consistently distribute a sufficient volume of high-quality products to the buyers is a key factor for a successful pooling operation. Successful pooling cases operate marketing contracts or agreements between member-farmers and cooperatives to make clear rights and duties of the two parties. The cases also show that the two parties endeavor to keep standards of quality specified in marketing agreements. Fair payment to member-farmers is definitely important for the successful pooling operations, especially in terms of prevention of free-riders and increase in participation of farmers with good-quality products. Education of member-farmers is also important because they need to understand cooperative’s identity and how its pooling system operates.

We outlined some successful cooperatives’ pooling cases in Korea. The cases might not be applied to cooperatives in other countries. How to construct the pooling program usually depends upon agricultural market characteristics of each country. A cooperative’s pooling program would be applied differently depending on characteristics of each product, composition of member-farmers, the market situation of each product, etc. However, agricultural cooperatives’ pooling would be important for the economic benefit of member-farmers in many countries, as their agricultural markets are increasingly globalized and concentrated by large-scale buyers.

REFERENCES

Buccola, S. T. 1994. Cooperatives. Encyclopedia of Agricultural Science vol.1: 431-440.

Chung J. H. and C. K. Yoo. 2014. Major factors for successful pool marketing of agricultural cooperatives and some implications (In Korean version). CEO Focus 335, Nonghyup Economic Research Institute.

Clark, E. 1952. Farmers Cooperatives and Economic Welfare, Journal of Farm Economics 34: 35-51.

Helmberger, P. and S. Hoos. 1962. Cooperative Enterprise and Organization theory. Journal of Farm Economics 44: 275-290.

LeVay, C. 1983a. Agricultural Co-operative Theory: A Review. Journal of Agricultural Economics 34(1983): 1-44.

LeVay, C. 1983b. Some problems of Agricultural Marketing Cooperatives’ Price/Output Determination in Imperfect Competition”, Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 31: 105-110.

Royer, J. S. 1987. Cooperative Theory: New Approaches. Service Report No. 18, Agricultural Cooperative Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Sexton, R. J., B. M. Wilson, and J. J. Wann, 1989. Some Tests of the Economic Theory of Cooperatives: Methodology and Application to Cotton Ginning, Western Journal of Agricultural Economics 14(1): 56-66.

Sexton, R. J. (1995). A perspective on Helmberger and Hoos’ theory of cooperatives. Journal of Cooperatives 10: 92-99.

Staatz, J. M. (1987). Recent development in the theory of agricultural cooperation. Journal of Agricultural Cooperation 2: 74-95.

[1] In figure 1 and 2, NARP (Net Average Revenue Product) is per-unit revenue less per-unit marketing cost such as grading, packing, and distribution, excluding the cost of raw product. Thus, NARP represents the full per-unit price that the cooperative can pay each farmer for raw product delivered. NMRP (Net Marginal Revenue Product) is the change in net revenue product, which is total revenue less marketing cost excluding cost of raw product, induced by an additional unit of raw product.

|

Submitted as a country report for the FFTC-NACF International Seminar on Improving Food Marketing Efficiency—the Role of Agricultural Cooperatives, Sept. 14-18, NACF, Seoul, Korea |

Agricultural Cooperatives’ Pooling Operations to Improve Marketing Efficiency in Korea

ABSTRACT

Agricultural cooperatives’ marketing business, especially on a pool basis, becomes more important as the agricultural market is increasingly globalized and concentrated by a few large-scale supermarkets. If agricultural cooperatives’ pooling is operated sufficiently in large, it would contribute to an efficiency-increase of the agricultural market through the ‘competitive yardstick’ role. Furthermore it would induce a reduction of marketing cost in all units of volume of the pooled products. Through the pooling’s effects, ultimately member-farmers would receive a higher price on raw products that they deliver. This paper introduces some successful pooling cases of agricultural cooperatives in Korea. Some factors, which include marketing agreements, quality management, fair pool-based payment, and education for farmers, are found to be important for successful pooling operations. Although a pooling program may be applied differently to agricultural cooperatives depending on each country, it can be an effective measure for member-farmers’ economic benefits, considering current market changes.

Key words: agricultural cooperative, pooling program, marketing efficiency

Introduction

Korea has experienced a significant transition in the agricultural market since the mid- 1990s. Since 1995, when the URAA (Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture) went into effect, the Korean agricultural market has been almost fully opened by converting import restrictions into tariffs. Furthermore, due to FTAs (Free Trade Agreements) with large countries in the agricultural industry, such as the USA and EU, import of agricultural products has significantly increased. From 1995 to 2014, imports of agricultural products increased by about 260% from $6.9 billion to $24.9 billion. Import of agricultural product is predicted to further increase as FTAs with many countries are implemented.

Moreover, the domestic agricultural marketing system has significantly changed in Korea. Since the early 2000’s, a few large supermarkets have rapidly grown in terms of retail-market share of agricultural products and their market power against farmers has been increasing. Thus, Korean farmers are now faced with the challenge of competing with foreign agricultural products while simultaneously coping with the increasing market power of the large-scale supermarkets. However, it is definitely not easy for farmers, particularly small-scale farmers, to do the tasks individually. Therefore, the role of agricultural cooperatives is becoming more important in the Korean agricultural market.

Agricultural cooperatives can contribute to an increase in member-farmers’ economic benefit by strengthening pooling operations. Pooling is a marketing practice specialized for cooperatives, which includes collecting, grading, packing, and distributing agricultural products as well as paying member-farmers on a group basis after selling their final products. By pooling, agricultural cooperatives can increase their bargaining power against large-scale buyers and reduce marketing costs throughout all stages from collection to final sale of the products. Therefore, pooling contributes to a higher price on raw products, so member-farmers receive increased returns.

It follows, then, that strengthening the cooperatives’ pooling system is one of the most important measures to effectively compete with imported agricultural products and cope with the increased buyers’ market power. Considering these points, Korean agricultural cooperatives have recently tried to establish more activated pooling organizations, which are operated by contracts or agreements between cooperatives and farmers. Furthermore, the agricultural cooperatives have pursued joint marketing among themselves in order to increase the pooling effects. As a result, a number of successful pooling cases have emerged and they are becoming good examples to other agricultural cooperatives in Korea.

The objective of this paper is to introduce some agricultural cooperatives’ pooling cases in Korea and derive implications for successful pooing operations. For this purpose, this paper first reviews some advantages of the cooperatives’ pooling operations, especially in terms of marketing efficiency, with brief theoretical concepts. It then overviews recent efforts of agricultural cooperatives to activate pooling operations and derives major factors for successful pooling operations through some useful cases. Then conclusions and implications are provided in the final section.

Some advantages of agricultural cooperatives’ pooling

The agricultural market, especially the vegetable and fruit markets, consists of a large number of small-scale farmers and a small number of large-scale buyers. This market condition is usually referred to as oligopsony in economics, and under such a condition, farmers are in a much weaker position than the buyers in terms of market power. Therefore, farmers usually receive a lower price in that market than they do in a competitive market. However, if farmers use a cooperative’s pooling system, they are expected to receive a higher price due to increased bargaining power by pooling.

If an agricultural cooperative constructs a strong pooling system in terms of volume and quality of raw product delivered by farmers, it would induce purchasing competition among the buyers and thereby contribute to farmers receiving higher prices. Ultimately, it would also contribute to an increase in efficiency of the agricultural market through making resource allocation more efficient. This is known as cooperative’s ‘competitive yardstick’ role. Another advantage of cooperative’s pooling operations is to improve efficiency of marketing-cost structure by both economies of scale and reduction of per-unit marketing cost. The cooperative’s pooling system allows farmers’ individual expenses related to activities after the harvest, such as grading, packing, and distribution, to spread out over a larger volume of raw product that they delivered to the cooperative.

The supply of raw product rises as the farmers participating in the cooperative’s pooling system grow in number. Figure 1 shows that the price of raw product goes up from r1 to r2 by economies of scale as the supply rises from S1 to S2.[1] Consider that the pooling of an agricultural cooperative is small scale. Then the cooperative faces an upward-sloping NARP (Net average revenue product) curve, or equivalently, a downward-sloping average processing cost curve. Hence, economies of scale are present in this case because the average processing cost falls as the quantity of raw product rises. Thus, making the pooling scale sufficiently large, through inducing more farmers’ participation, is an important task for the cooperative with a small pooling scale, as shown in Fig. 1.

Another possible choice for larger scale pooling is to build a joint marketing system among cooperatives. If this were feasible, per-unit marketing costs would be reduced in all units of volume of raw product that member-farmers deliver. Figure 2 shows that price of raw product goes up from r3 to r4 by reduction of per unit marketing cost in all units of volume. The NARP curve itself shifts upward as per unit marketing cost decreases in all units of volume. Thus, if the pooling scale is sufficiently large, farmers participating in the pooling system are expected to receive a higher price than before by both the increased supply and the shift upward of NARP in all units of volume as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1. Effects of cooperative’s pooling in terms of ‘economies of scale’

Fig. 2. Effects of cooperative’s pooling in terms of marketing-cost reduction

Cases of agricultural cooperatives’ pooling in Korea

Overview of pooling operations

In general, member-farmers of the local agricultural cooperative have no obligation to deliver the raw products that they produce to their cooperatives. Thus, participation of member-farmers in the cooperative’s marketing business is not sufficient and usually their pooling scale is small. This is a structural problem in that cooperatives have difficulty sufficiently scaling marketing business. To overcome this problem, a number of local agricultural cooperatives have voluntarily established product-specific pooling organizations, which are operated by marketing agreements between the cooperatives and member-farmers, since the mid-2000s. Usually, a local agricultural cooperative operates the pooling organizations for more than one product. For example, a cooperative operates grape, peach, and potato pooling organizations separately. In 2014, there were about 1,900 pooling organizations in operation nationwide. Sales of the pooling organizations increased by 178% from 2009 to 2014 (Figure 3).

Korean agriculture is characterized by small-scale family farms. Per-farm household cultivation area is approximately 1.5ha on average. Because of this, a local cooperative can operate the pooling organization but it usually lacks marketing scaling large enough to have bargaining power against large-scale buyers. Hence, since the mid-2000s, some local agricultural cooperatives have tried to make the pooling scale be larger by pursuing joint marketing among the cooperatives. For this, they have established secondary marketing organizations by joint investments. Currently, about 50 secondary marketing organizations are being operated nationwide with marketing-specialized roles.

Fig. 3. Sales of pooling organizations in Korea during 2009~2014

Major factors in successful pooling cases

The agricultural cooperative needs to handle a sufficiently large volume with high-quality products in order to increase its marketing power against buyers. For this, the binding marketing contract or agreement between the cooperative and member-farmers is important in its marketing business. The agreement includes the rights, duties, and responsibilities of both parties relevant to the cooperative marketing.

The local agricultural cooperatives that operate the pooling organizations usually make the marketing agreement. In most cases, based on the agreement, farmers deliver all or part of their products to the cooperatives. Also, they cultivate a specific variety of a product and complete a study course for quality management. The cooperative, also according to the agreement, instructs members’ farming activities, such as variety choice, time control of sowing and harvesting, and cultivation techniques.

In general, the agreement sets a penalty, to be applied if farmers violate the rules, especially pertaining to volume of delivery and criteria of quality. In most cases, if a farmer does violate the rules, he is dismissed from the pooling organization directly or after a warning depending upon the marketing agreement. In the actual case of a local cooperative in 2011, about 60 percent of farmers who belonged to a grape pooling organization violated a delivery rule by selling their grape to other merchants. At that time, the organization held a general meeting and decided to disband itself. Then, the organization was newly established with the condition that if a farmer violates the rule even at one time, he is dismissed without any warning. Since then, the pooling organization has seen no violations of its rules.

Quality control of agricultural products is a key factor in stabilizing the cooperative’s marketing business. By providing good-quality products consistently with consideration of consumers’ preferences, the cooperative can enhance its marketing ability. If we look to a successful case, we can see that the pooling organization tries to manage quality of products throughout all pooling stages, from cultivation to delivery.

In the cultivation stage, the cooperative instructs farmers to unify a variety of a products, agricultural supplies, and cultivation techniques with expert consultation. After the harvest, the cooperative grades the farmers’ products following the selection standards including size, appearance, color, sugar content, etc. Grading is conducted in a marketing facility with functions of packing, storing, and distributing as well as grading. Any farmer is prohibited from being involved in the process of grading for fairness. After grading, the products that do not satisfy the selection standards are sold separately, being excluded from the pooled products. The following is an example of good quality management system.

Example: Quality management process of a local agricultural cooperative

Fair payment after the sale of final products is a critical factor for the cooperative’s successful pooling operations. It prevents free-riders and increases the participation of better farmers in terms of product quality. If the same amount is paid to all member-farmers on the basis of average, regardless of quality, some farmers who delivered higher-quality products would make a loss and might secede from the pooling organization due to dissatisfaction with the payment.

The successful cooperatives in the pooling operations commonly emphasize fair payment. In many cases, an incentive is paid to farmers who delivered higher-quality products. This is of course facilitated by member-farmers’ consensus. The incentive-payment system would be useful for overall quality enhancement of raw products delivered by member-farmers, encouraging them to strive for quality management. The following is an example of the incentive-payment system of a local agricultural cooperative.

Member-farmers’ positive participation is important for the sustainable development of the cooperative’s pool marketing. The pooling effects, mentioned previously, can become greater if all member-farmers try to deliver high-quality products with a shared philosophy on pooling and a firm belief in cooperative’s pool marketing. Thus, the cooperative needs to operate an effective education system to pursue an increase in farmers’ understanding on pooling and thereby induce positive participation. An example of the education system is as follows:

Example: A six-step education system of a local agricultural cooperative

The price of agricultural products is usually inelastic with respect to supply and demand. Thus, even a little change in supply or demand can cause market prices of the products to fluctuate severely. Therefore, the agricultural cooperative needs to hedge against some unexpected changes, like a sharp fall in price, for its stable pool marketing. In some successful cases, the cooperative and member-farmers belonging to the pooling organization raise funds jointly in order to hedge against the risk like unexpected price-fall. The funds are also used for the purpose of joint activities, which are relevant to farming like pest control on a group basis, of the pooling organization. The cooperatives that operate the joint funding system usually raise amount by 0.5 or 1% of total sales. The joint funding is feasible only with consensus of member-farmers of the pooling organization.

Joint marketing among local agricultural cooperatives can increase market power and reduce marketing cost, thereby contributing greater economic benefit to member-farmers of each cooperative. Since the mid 2000s, some local agricultural cooperatives established secondary marketing organizations through joint investments, mostly on the county and city levels. In a successful case, systemization among the primary pooling organizations, the local cooperatives, and the secondary marketing organization is constructed with each having its role assignment as follows:

The member-farmers belonging to the pooling organizations deliver high-quality products to their local cooperatives according to marketing agreements. The local agricultural cooperatives provide member-farmers with support and education about cultivation technique, quality management, and other farming activities. Moreover, they jointly grade the delivered products in marketing facilities then consign the products to the secondary marketing organization that they invested in.

The secondary marketing organization is wholly responsible for marketing activities, including development of new buyers, sales strategies targeting each buyer, promotion of the joint brand, etc. Buyers generally include wholesale markets, large-scale supermarkets, food-processing companies, retail stores, etc. After finally selling the products, the secondary marketing organizations pay the joined local cooperatives on a pool basis. Then, each cooperative pays its member-farmers returns for the raw products they delivered. The following is a case of systemization among pooling organizations, local agricultural cooperatives, and their secondary marketing organization.

Example: A case of linkage among pooling organizations, local agricultural cooperatives, and secondary marketing organization

CONCLUSION

The main objective of agricultural cooperatives is to maximize member-farmers’ economic benefits. This can be achieved by providing member-farmers with greater returns on raw products through the cooperatives’ marketing business. Whether the objective can be achieved depends upon the extent of the cooperatives’ bargaining power against large-scale buyers, especially in an imperfect competition market. Thus, it is important that the cooperatives try to achieve a balance in market power with the buyers by establishing a large-scale pooling system. Pooling is a marketing activity distinct to cooperatives and generally includes collecting, grading, packing, storing, and selling agricultural products delivered by member-farmers then distributing payment on a group basis after selling the final products.

Agricultural cooperatives can increase their bargaining power with a sufficiently large pooling system and thereby induce the buyers’ purchasing competition. This makes the agricultural market more efficient, which is known as cooperative’s ‘competitive-yardstick’ role. Through this role, the cooperatives ultimately provide member-farmers with more returns on the raw products they delivered. The pooling system can also lead to a reduction of marketing costs in each volume unit of the products by spreading out the cost over the collected products, which also contributes to providing member-farmers with greater returns.

However, effectively operating a stable pooling system is more important than simply constructing the system. To consistently distribute a sufficient volume of high-quality products to the buyers is a key factor for a successful pooling operation. Successful pooling cases operate marketing contracts or agreements between member-farmers and cooperatives to make clear rights and duties of the two parties. The cases also show that the two parties endeavor to keep standards of quality specified in marketing agreements. Fair payment to member-farmers is definitely important for the successful pooling operations, especially in terms of prevention of free-riders and increase in participation of farmers with good-quality products. Education of member-farmers is also important because they need to understand cooperative’s identity and how its pooling system operates.

We outlined some successful cooperatives’ pooling cases in Korea. The cases might not be applied to cooperatives in other countries. How to construct the pooling program usually depends upon agricultural market characteristics of each country. A cooperative’s pooling program would be applied differently depending on characteristics of each product, composition of member-farmers, the market situation of each product, etc. However, agricultural cooperatives’ pooling would be important for the economic benefit of member-farmers in many countries, as their agricultural markets are increasingly globalized and concentrated by large-scale buyers.

REFERENCES

Buccola, S. T. 1994. Cooperatives. Encyclopedia of Agricultural Science vol.1: 431-440.

Chung J. H. and C. K. Yoo. 2014. Major factors for successful pool marketing of agricultural cooperatives and some implications (In Korean version). CEO Focus 335, Nonghyup Economic Research Institute.

Clark, E. 1952. Farmers Cooperatives and Economic Welfare, Journal of Farm Economics 34: 35-51.

Helmberger, P. and S. Hoos. 1962. Cooperative Enterprise and Organization theory. Journal of Farm Economics 44: 275-290.

LeVay, C. 1983a. Agricultural Co-operative Theory: A Review. Journal of Agricultural Economics 34(1983): 1-44.

LeVay, C. 1983b. Some problems of Agricultural Marketing Cooperatives’ Price/Output Determination in Imperfect Competition”, Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics 31: 105-110.

Royer, J. S. 1987. Cooperative Theory: New Approaches. Service Report No. 18, Agricultural Cooperative Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Sexton, R. J., B. M. Wilson, and J. J. Wann, 1989. Some Tests of the Economic Theory of Cooperatives: Methodology and Application to Cotton Ginning, Western Journal of Agricultural Economics 14(1): 56-66.

Sexton, R. J. (1995). A perspective on Helmberger and Hoos’ theory of cooperatives. Journal of Cooperatives 10: 92-99.

Staatz, J. M. (1987). Recent development in the theory of agricultural cooperation. Journal of Agricultural Cooperation 2: 74-95.

[1] In figure 1 and 2, NARP (Net Average Revenue Product) is per-unit revenue less per-unit marketing cost such as grading, packing, and distribution, excluding the cost of raw product. Thus, NARP represents the full per-unit price that the cooperative can pay each farmer for raw product delivered. NMRP (Net Marginal Revenue Product) is the change in net revenue product, which is total revenue less marketing cost excluding cost of raw product, induced by an additional unit of raw product.