Yoshihisa Godo

Professor, Meiji Gakuin University, Japan

Rice is the staple food in Japan. Thus, the Japanese government is paying special attention to rice contamination by cesium after the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident of March 2011. This article aims to describe the government’s attempts to prevent rice that is highly contaminated with cesium from reaching the markets.

On March 17, 2011, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) set the provisional regulation value for cesium contamination in rice at 500 Bq/kg1. Thereafter, in order to prevent rice contaminated beyond this level from being marketed, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) established regulations for rice planting. Specifically, rice planting was prohibited in the evacuation zone, the planned evacuation zone, and the emergency evacuation preparation zone2. In addition, assuming a cesium transfer rate from soil to rice grains of 0.1, rice planting was prohibited in paddy fields where the cesium level was more than 5,000 Bq/kg3.

For paddy fields where the cesium level was less than 5,000 Bq/kg, rice planting was permitted. However, the MAFF employed a system for monitoring cesium contamination levels of rice even after planting, as described in Figure 1. Before harvest, the MAFF conducted preliminary tests on cesium contamination levels to estimate the level of such contamination of rice at harvest. Thus, preliminary tests were performed at 824 sites in 17 prefectures, namely, Akita, Aomori, Chiba, Fukushima, Gunma, Ibaraki, Iwate, Kanagawa, Miyagi, Nagano, Niigata, Saitama, Shizuoka, Tochigi, Tokyo, Yamagata and Yamanashi. Of these sites, cesium contamination in rice at levels between 300 and 500 Bq/kg was found at 1 site, at levels between 100 and 200 Bq/kg was found at 5 sites, and at levels between 20 and 100 Bq/kg was found at 119 sites4. For the remaining 699 sites, the contamination level is referred to as “not detected (ND),” which means that cesium contamination was less than the limit of detection by sensors. In the preliminary tests, in no cases did the level of such contamination exceed the provisional regulation value. Apparently, this was a good sign for selling rice after harvest.

After harvest and before shipping, final tests were conducted at 3,215 sites in the 17 prefectures. At site 1, cesium contamination of rice was at a level between 300 and 500 Bq/kg (note 5). At site 7, such contamination was at levels between 100 and 200 Bq/kg (note 6). At 228 sites, it was at levels between 20 and 100 Bq/kg7. At the remaining 2,979 sites, this contamination was ND. At no site did the contamination exceed the level of regulation value (i.e., 500 Bq/kg). Based on the results of the final tests, many prefectures issued a “Declaration of Safety on Rice.” For example, Fukushima issued such a declaration on October 12, 2011.

However, these declarations did not remove consumers’ anxiety about radiation contamination of rice. Damage caused by rumors was one of the biggest problems for rice farmers, in particular, in East Japan. For example, there was a tendency among consumers to prefer rice produced in 2010 or 2011 in prefectures that were far from Fukushima. It was not rare for agricultural cooperatives, supermarkets, and cooperative stores to conduct their own radiation contamination tests on rice in addition to the MAFF’s official tests and to sell only rice that proved to be ND.

Sensational news appeared in November 16, 2011, eight months after the nuclear accident. Agricultural cooperatives in Fukushima conducted their own cesium tests for rice that had passed the MAFF’s monitoring system (shown in Figure 1) and was, therefore, allowed to be sold by the MAFF. The cooperatives found several cases in which the rice was actually contaminated with cesium at levels higher than the provisional regulation value set by the MHLW. The highest case showed contamination of 1,270 Bq/kg, which was more than double the provisional regulation value of 500 Bq/kg. While the number of such cases was quite limited, this news shocked consumers, who began to question critically the reliability of the MAFF and prefectural governments to monitor cesium contamination of rice.

To mitigate consumers’ anxiety, the Fukushima prefectural government responded quickly to this news and prohibited the shipping of rice harvested in the three Fukushima municipalities in which the highly contaminated rice was found. In addition, the prefectural government launched emergency tests on cesium contamination of rice for all rice bags (a bag usually contains 60 kg of rice) before shipping from the areas of suspected high contamination. By doing so, the Fukushima prefectural government gave the assurance that no rice shipped from Fukushima would be contaminated with cesium at a level higher than the regulation value (500 Bq/kg). In spite of these measures, the bad reputation of Fukushima rice persists to date8.

On October 28, 2011, the MHLW lowered the regulation value for cesium contamination to 100 Bq/kg from 500 Bq/kg. The new regulation value was scheduled to become effective on April 1, 20129. However, immediately after the MHLW’s announcement, the MAFF started to procure rice contaminated with cesium at levels between 100 Bq/kg and 500 Bq/kg for disposal.

The MAFF prohibited rice planting in 2012 at the evacuation zone, the planned evacuation zone, the emergency evacuation preparation zone, and areas where rice contaminated with more than 500 Bq/kg of cesium was produced. The MAFF allowed rice planting in areas where cesium contamination of rice was at levels between 100 Bq/kg and 500 Bq/kg, on condition of (1) special treatment to reduce the transfer of cesium from soil to rice grains and (2) cesium tests on all rice bags before shipping. These regulations for rice planting have been maintained principally up until now.

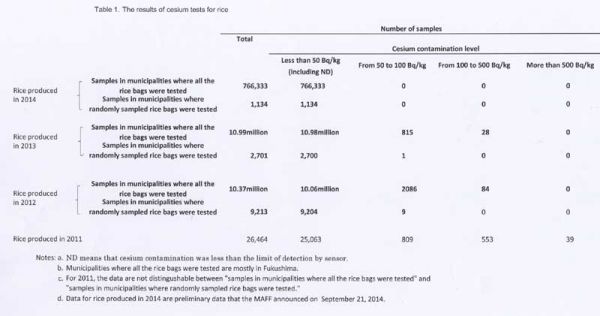

The results of the MAFF’s monitoring of cesium contamination of rice are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, the level of cesium contamination of rice has declined gradually.

FOOTNotes

- The basis of the regulation value of 500 Bq/kg is provided by Yoshihisa Godo, “Regulation values for radioactive materials in food after the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Database (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region), October 1, 2014.

- On April 22, 2011, the Nuclear Safety Commission designated the evacuation zone, the planned evacuation zone, and the emergency evacuation preparation zone based on the Act on Special Measures Concerning Nuclear Emergency Preparedness.

- The National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences conducted field studies on cesium in soil at 17 sites from 1959 to 2001. Based on the results of these studies, the MAFF estimated the cesium transfer rate from soil to rice grain at 0.1.

- Among the 119 sites, 8 sites were in Fukushima. 6 sites where cesium contamination of rice was more than 100 Bq/kg were in Fukushima.

- The site was in Fukushima.

- Among the 7 sites, 6 were in Fukushima.

- Among the 118 sites, 111 were in Fukushima.

- For example, see “Beika Kyuraku, Seisanhi no Han-ne (Sharp Drop in Rice Price, Covering only Half of Rice Production Costs),” Asahi Shimbun (Fukushima Edition), October 21, page 29.

- The basis of the new regulation value of 100 Bq/kg is given in Yoshihisa Godo, op. cit.

|

Date submitted: Oct. 29, 2014

Received, edited and uploaded: Nov. 4, 2014

|

Food Safety Measures to Cope with Cesium Contamination in Rice after the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident

Yoshihisa Godo

Professor, Meiji Gakuin University, Japan

Rice is the staple food in Japan. Thus, the Japanese government is paying special attention to rice contamination by cesium after the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident of March 2011. This article aims to describe the government’s attempts to prevent rice that is highly contaminated with cesium from reaching the markets.

On March 17, 2011, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) set the provisional regulation value for cesium contamination in rice at 500 Bq/kg1. Thereafter, in order to prevent rice contaminated beyond this level from being marketed, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) established regulations for rice planting. Specifically, rice planting was prohibited in the evacuation zone, the planned evacuation zone, and the emergency evacuation preparation zone2. In addition, assuming a cesium transfer rate from soil to rice grains of 0.1, rice planting was prohibited in paddy fields where the cesium level was more than 5,000 Bq/kg3.

For paddy fields where the cesium level was less than 5,000 Bq/kg, rice planting was permitted. However, the MAFF employed a system for monitoring cesium contamination levels of rice even after planting, as described in Figure 1. Before harvest, the MAFF conducted preliminary tests on cesium contamination levels to estimate the level of such contamination of rice at harvest. Thus, preliminary tests were performed at 824 sites in 17 prefectures, namely, Akita, Aomori, Chiba, Fukushima, Gunma, Ibaraki, Iwate, Kanagawa, Miyagi, Nagano, Niigata, Saitama, Shizuoka, Tochigi, Tokyo, Yamagata and Yamanashi. Of these sites, cesium contamination in rice at levels between 300 and 500 Bq/kg was found at 1 site, at levels between 100 and 200 Bq/kg was found at 5 sites, and at levels between 20 and 100 Bq/kg was found at 119 sites4. For the remaining 699 sites, the contamination level is referred to as “not detected (ND),” which means that cesium contamination was less than the limit of detection by sensors. In the preliminary tests, in no cases did the level of such contamination exceed the provisional regulation value. Apparently, this was a good sign for selling rice after harvest.

After harvest and before shipping, final tests were conducted at 3,215 sites in the 17 prefectures. At site 1, cesium contamination of rice was at a level between 300 and 500 Bq/kg (note 5). At site 7, such contamination was at levels between 100 and 200 Bq/kg (note 6). At 228 sites, it was at levels between 20 and 100 Bq/kg7. At the remaining 2,979 sites, this contamination was ND. At no site did the contamination exceed the level of regulation value (i.e., 500 Bq/kg). Based on the results of the final tests, many prefectures issued a “Declaration of Safety on Rice.” For example, Fukushima issued such a declaration on October 12, 2011.

However, these declarations did not remove consumers’ anxiety about radiation contamination of rice. Damage caused by rumors was one of the biggest problems for rice farmers, in particular, in East Japan. For example, there was a tendency among consumers to prefer rice produced in 2010 or 2011 in prefectures that were far from Fukushima. It was not rare for agricultural cooperatives, supermarkets, and cooperative stores to conduct their own radiation contamination tests on rice in addition to the MAFF’s official tests and to sell only rice that proved to be ND.

Sensational news appeared in November 16, 2011, eight months after the nuclear accident. Agricultural cooperatives in Fukushima conducted their own cesium tests for rice that had passed the MAFF’s monitoring system (shown in Figure 1) and was, therefore, allowed to be sold by the MAFF. The cooperatives found several cases in which the rice was actually contaminated with cesium at levels higher than the provisional regulation value set by the MHLW. The highest case showed contamination of 1,270 Bq/kg, which was more than double the provisional regulation value of 500 Bq/kg. While the number of such cases was quite limited, this news shocked consumers, who began to question critically the reliability of the MAFF and prefectural governments to monitor cesium contamination of rice.

To mitigate consumers’ anxiety, the Fukushima prefectural government responded quickly to this news and prohibited the shipping of rice harvested in the three Fukushima municipalities in which the highly contaminated rice was found. In addition, the prefectural government launched emergency tests on cesium contamination of rice for all rice bags (a bag usually contains 60 kg of rice) before shipping from the areas of suspected high contamination. By doing so, the Fukushima prefectural government gave the assurance that no rice shipped from Fukushima would be contaminated with cesium at a level higher than the regulation value (500 Bq/kg). In spite of these measures, the bad reputation of Fukushima rice persists to date8.

On October 28, 2011, the MHLW lowered the regulation value for cesium contamination to 100 Bq/kg from 500 Bq/kg. The new regulation value was scheduled to become effective on April 1, 20129. However, immediately after the MHLW’s announcement, the MAFF started to procure rice contaminated with cesium at levels between 100 Bq/kg and 500 Bq/kg for disposal.

The MAFF prohibited rice planting in 2012 at the evacuation zone, the planned evacuation zone, the emergency evacuation preparation zone, and areas where rice contaminated with more than 500 Bq/kg of cesium was produced. The MAFF allowed rice planting in areas where cesium contamination of rice was at levels between 100 Bq/kg and 500 Bq/kg, on condition of (1) special treatment to reduce the transfer of cesium from soil to rice grains and (2) cesium tests on all rice bags before shipping. These regulations for rice planting have been maintained principally up until now.

The results of the MAFF’s monitoring of cesium contamination of rice are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, the level of cesium contamination of rice has declined gradually.

FOOTNotes

Date submitted: Oct. 29, 2014

Received, edited and uploaded: Nov. 4, 2014