Yoshihisa GODO

Professor, Meiji Gakuin University, Japan

Japan is a mountainous country, with only 33% of its total land acreage as flat area. Japan’s flat land area is much smaller than that of other, major developed countries such as the United States with 70% of its total land area as flat land, United Kingdom with 90% flat land area, Italy with 77%, France with 73%, and Germany with 69%.

Japan’s predominantly mountainous landscape poses a problem for land use and has triggered a conflict between agricultural and non-agricultural land use of limited high-quality land. The favorable land conditions for farming are (1) flatness, (2) large well-shaped land block, (3) good access to roads, (4) presence of abundant sunlight, and (5) good water drainage system. These five conditions are also favorable for urban land uses such as construction of shopping centers, apartments, and public facilities.

Generally, profit per acreage for agriculture is much lower than potential for profits per acreage in non-agriculture. Thus, it would appear that most high-quality farmlands would inevitably be converted to non-agricultural purposes without regulation of land use. Farmlands have several economic externalities. First, farmlands have water retention function, which prevents flooding of rivers during periods of heavy rainfall. Second, farmland is a habitat for endangered species. Third, farmland is the foundation of rural life. Moreover, it is difficult to restore a farmland once it has been converted to non-agricultural purposes. Thus, it is reasonable for the government to set regulations of farmland conversion.

While it is not necessary to protect all farmlands from conversion for non-agricultural purposes, conversions should be carried out in a well-planned manner. Ensuring proper planning for farmland conversion is one of the most essential aspects of farmland policy.

In the early postwar period, the conflict between agricultural land use and non-agricultural land use was not very intense, primarily because of the de-urbanization process in the aftermath of the Pacific War. The war caused heavy damage in urban areas and large factories and urban infrastructure were major targets of US bombings. As a result, rural workers who had earlier migrated to urban areas lost their jobs and returned home. Japanese immigrants in the colonies and soldiers from overseas war fronts also returned to Japan and started farming enterprises, leading to further de-urbanization after the war.

However, the process of urbanization restarted when Japan entered the high growth era. The DID population increased from 41 million in 1965 to 47 million in 1970 and it was projected to reach around 100 million by 1985. Corresponding to this period of DID population rise, farmland was converted for non-agricultural purposes in unplanned ways. As a result of disorder in land use, shortages in public services such as water and power supply became an enormous problem in urban areas. Loss of high-quality farmland was also alleged to have led to food insecurity in Japan. In this situation, the Japanese government introduced the system of controlling farmland conversion in the early 1970s. Although the system has been revised a number of times since its introduction, its fundamental structure remains the same until today.

The system of controlling farmland conversion comprises many laws. Three major laws in this context are the City Planning Law (CPL), the Agricultural Land Law (ALL), and the Law concerning Construction of Agricultural Promotion Areas (LCAPA). The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation (MLIT) is responsible for implementing CPL and the Ministry of

The purpose of controlling land use is different for MLIT and MAFF. While the purpose of MAFF is to protect high-quality farmland from conversion, MLIT aims to ensure proper economic and living conditions for the urban dwellers/urbanite after the farmland is converted to non-agricultural purposes. For constructing non-agricultural facilities on farmland, one must satisfy both MAFF conditions for converting farmlands and MLIT conditions for constructing non-agricultural facilities.

CPL stipulates regulations for land development (for both farmland and non-farmland). Development here refers to the process of converting land for a new purpose by constructing buildings or making use of its resources. A landowner intending to develop his land must submit details of the development plan to the prefectural government, who will inspect feasibility and suitability of the plan for land use.

CPL has a zoning regulation on land (for both farmland and non-farmland), wherein prefectural governments set the zoning of the “area designated for urbanization” (ADU) and “urbanization control area” (UCA). Theoretically, under ADU, farmlands should be converted for non-agricultural purposes within a period of ten years.

In ADU, MAFF imposes no regulations on farmland conversion for non-agricultural purposes. Additionally, the preferential tax system for farmland is not applied under ADU. Access value of farmland in ADU is generally high because it is evaluated based on the potential value that can be obtained if the farmland was converted to non-agricultural purposes, rather than the earning capacity of the farmland from agriculture.

Farmers in ADU are usually under pressure for farmland conversion. Since the farmland size in ADU is too small to have the aforementioned economic externalities and ADU has high population density, it seems rational that farmland under ADU should be promptly converted to non-agricultural purposes. However, it is argued that farmlands in ADU need to be protected from conversion for a different set of reasons. First, greenery of farmlands adds to the comforts of urban life, improves the urban environment, and beautifies the urban landscape. Second, fresh vegetables from farmlands in ADU improve the health of urban dwellers. Third, farmlands in ADU could potentially serve as a place of safety for safeguarding urban dwellers against disasters (e.g., earthquakes and fires). Fourth, farmlands in ADU are convenient spots for building public facilities in the future. Although farmlands in ADU have these economic externalities, selective, and not all, farmlands should be targeted for protection. To this end, MLIT has a law called the Productive Green Land Act (PGLA), under which local governments in the three major metropolitan areas (Tokyo, Kinki, and Chubu) designate selected parcels of farmland in their jurisdictions as Productive Green Land (PGL). Once a parcel of farmland is designated as PGL, the owner (farmer) is obliged to continue farming in that farmland for the next 30 years. Since this law fixes land use for a period of 30 years, local governments must observe prudence in designating farmlands as PGL. The process involves close interaction between local governments and landowners for determining which farmlands should be designated as PGL. After the passage of 30 years since the designation of PGL, the landowner has the right to make a claim for the local government to purchase his farmland. In case the landowner waives the claim, the local government decides whether the PGL designation should be renewed for another 30 years. The asset tax structure imposed on farmlands in PGL is far less stringent than taxes on farmlands in ADU (the tax authority assesses taxes for farmlands in PGL based on their earning capacity for agricultural purpose). However, farmlands in PGL are, in principle, prohibited from conversion for non-agricultural purposes.

CPL stipulates that development plans should be approved for UCA only if there are rational reasons for not including those plans under ADU. Furthermore, it should be ensured that the plans do not prompt other development plans under the UCA umbrella. Development Investigation Committees established in every prefecture, ordinance-designated city, nucleated city, and special city, are responsible for ascertaining whether a particular plan qualifies for approval.

In addition to the MLIT zoning regulation of ADU and UCA, MAFF also has its own zoning regulation based on LCAPA. Under this system of regulation, municipal governments designate zoning of Exclusively Agricultural Area (EAA) for provision of preferential treatment entailing agricultural subsidies and tax reduction. In EAA, farmlands are prohibited from being converted. EAA comprises nearly 80% of total farmland area in Japan. Please note that while farmlands under ADU are not included in EAA, majority of farmlands covered by CPA is included in EAA.

Municipal governments revise EAA zoning as necessary. According to MAFF guidelines, every municipal government should incorporate EAA zoning plans in its ten-year plan and should not change the zoning system introduced for at least five years. However, this guideline is only recommendatory in nature and is not legally enforceable. As a result, majority of municipal governments do not observe strict adherence to this guideline and in actual practice, EAA zoning is frequently revised to entertain requests of farmland owners.

Conversion of farmlands under EAA and ADU for non-agricultural purpose is possible if landowners receive permission based on ALL. When a landowner seeks to convert a farmland area of more than 2.0 hectare, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries is responsible for issuing permission for farmland conversion. The responsibility rests with the prefectural governor in all other cases. ALL classifies farmlands into three categories according to quality of the farmland: Type I (high quality), Type II (medium quality), and Type III (low quality). Type III farmlands should be permitted for conversion unless there are special reasons for not doing so. In the case of EAA zoning, a landowner is aware whether his farmland is in EAA. On the contrary, classification into Types I, II, or III is done only after the landowner submits an application of farmland conversion plan. Farmlands of Types I and II should be ideally protected from farmland conversion. However, if the competent authority recognizes that the farmland conversion plan would potentially benefit the local community and there are no suitable alternatives available under Type III or both Types II and III, permission for conversion of Type II or Type I farmland may be issued.

As can be seen in Figure 1, farmland owners receive substantial capital gains from farmland conversion. The expectation of future opportunities for farmland conversion triggers a rise in farmland prices much higher than their earning capacity for farming. High prices prevail even in cases where farmlands are traded between farmers for agricultural purpose.

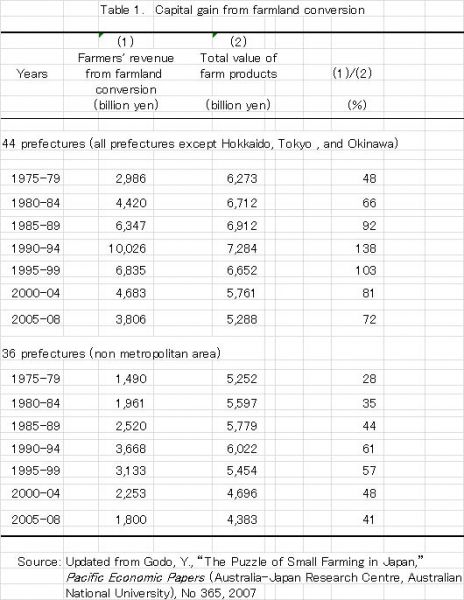

Although there are no official statistics on farmer revenues from farmland conversions, this study has estimated it based on various data sources (Godo, Y., “The Puzzle of Small Farming in Japan,” Pacific Economic Papers, No 365, 2007). The results are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, revenue from farmland conversions is nearly 40% of the total value of farm products even in non-metropolitan areas. Since farmers obtained (or inherited) their farmlands at a very low cost, this revenue can be considered a clear profit. Even rice production, Japan’s most important crop, shares only one-fourth of the total value of farm products. Thus, Table 1 shows that capital gains from farmland conversions are larger than profits made from crop production.

Additionally, Table 1 presents the downward trend in capital gains from farmland conversions over the past 15 years. This reflects the reduced rate of public constructions and large-scale development plans after the collapse of the “bubble” in the early 1990s. However, there is evidence that illegal farmland conversions have increased during the past 15 years. Since data in Table 1 pertains to legal farmland conversions, in real practice, capital gains may not have decreased over this period.

|

Date submitted: October 5, 2013

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: October 8, 2013

|

Regulation of Farmland Conversion in Japan

Yoshihisa GODO

Professor, Meiji Gakuin University, Japan

Japan is a mountainous country, with only 33% of its total land acreage as flat area. Japan’s flat land area is much smaller than that of other, major developed countries such as the United States with 70% of its total land area as flat land, United Kingdom with 90% flat land area, Italy with 77%, France with 73%, and Germany with 69%.

Japan’s predominantly mountainous landscape poses a problem for land use and has triggered a conflict between agricultural and non-agricultural land use of limited high-quality land. The favorable land conditions for farming are (1) flatness, (2) large well-shaped land block, (3) good access to roads, (4) presence of abundant sunlight, and (5) good water drainage system. These five conditions are also favorable for urban land uses such as construction of shopping centers, apartments, and public facilities.

Generally, profit per acreage for agriculture is much lower than potential for profits per acreage in non-agriculture. Thus, it would appear that most high-quality farmlands would inevitably be converted to non-agricultural purposes without regulation of land use. Farmlands have several economic externalities. First, farmlands have water retention function, which prevents flooding of rivers during periods of heavy rainfall. Second, farmland is a habitat for endangered species. Third, farmland is the foundation of rural life. Moreover, it is difficult to restore a farmland once it has been converted to non-agricultural purposes. Thus, it is reasonable for the government to set regulations of farmland conversion.

While it is not necessary to protect all farmlands from conversion for non-agricultural purposes, conversions should be carried out in a well-planned manner. Ensuring proper planning for farmland conversion is one of the most essential aspects of farmland policy.

In the early postwar period, the conflict between agricultural land use and non-agricultural land use was not very intense, primarily because of the de-urbanization process in the aftermath of the Pacific War. The war caused heavy damage in urban areas and large factories and urban infrastructure were major targets of US bombings. As a result, rural workers who had earlier migrated to urban areas lost their jobs and returned home. Japanese immigrants in the colonies and soldiers from overseas war fronts also returned to Japan and started farming enterprises, leading to further de-urbanization after the war.

However, the process of urbanization restarted when Japan entered the high growth era. The DID population increased from 41 million in 1965 to 47 million in 1970 and it was projected to reach around 100 million by 1985. Corresponding to this period of DID population rise, farmland was converted for non-agricultural purposes in unplanned ways. As a result of disorder in land use, shortages in public services such as water and power supply became an enormous problem in urban areas. Loss of high-quality farmland was also alleged to have led to food insecurity in Japan. In this situation, the Japanese government introduced the system of controlling farmland conversion in the early 1970s. Although the system has been revised a number of times since its introduction, its fundamental structure remains the same until today.

The system of controlling farmland conversion comprises many laws. Three major laws in this context are the City Planning Law (CPL), the Agricultural Land Law (ALL), and the Law concerning Construction of Agricultural Promotion Areas (LCAPA). The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation (MLIT) is responsible for implementing CPL and the Ministry of

The purpose of controlling land use is different for MLIT and MAFF. While the purpose of MAFF is to protect high-quality farmland from conversion, MLIT aims to ensure proper economic and living conditions for the urban dwellers/urbanite after the farmland is converted to non-agricultural purposes. For constructing non-agricultural facilities on farmland, one must satisfy both MAFF conditions for converting farmlands and MLIT conditions for constructing non-agricultural facilities.

CPL stipulates regulations for land development (for both farmland and non-farmland). Development here refers to the process of converting land for a new purpose by constructing buildings or making use of its resources. A landowner intending to develop his land must submit details of the development plan to the prefectural government, who will inspect feasibility and suitability of the plan for land use.

CPL has a zoning regulation on land (for both farmland and non-farmland), wherein prefectural governments set the zoning of the “area designated for urbanization” (ADU) and “urbanization control area” (UCA). Theoretically, under ADU, farmlands should be converted for non-agricultural purposes within a period of ten years.

In ADU, MAFF imposes no regulations on farmland conversion for non-agricultural purposes. Additionally, the preferential tax system for farmland is not applied under ADU. Access value of farmland in ADU is generally high because it is evaluated based on the potential value that can be obtained if the farmland was converted to non-agricultural purposes, rather than the earning capacity of the farmland from agriculture.

Farmers in ADU are usually under pressure for farmland conversion. Since the farmland size in ADU is too small to have the aforementioned economic externalities and ADU has high population density, it seems rational that farmland under ADU should be promptly converted to non-agricultural purposes. However, it is argued that farmlands in ADU need to be protected from conversion for a different set of reasons. First, greenery of farmlands adds to the comforts of urban life, improves the urban environment, and beautifies the urban landscape. Second, fresh vegetables from farmlands in ADU improve the health of urban dwellers. Third, farmlands in ADU could potentially serve as a place of safety for safeguarding urban dwellers against disasters (e.g., earthquakes and fires). Fourth, farmlands in ADU are convenient spots for building public facilities in the future. Although farmlands in ADU have these economic externalities, selective, and not all, farmlands should be targeted for protection. To this end, MLIT has a law called the Productive Green Land Act (PGLA), under which local governments in the three major metropolitan areas (Tokyo, Kinki, and Chubu) designate selected parcels of farmland in their jurisdictions as Productive Green Land (PGL). Once a parcel of farmland is designated as PGL, the owner (farmer) is obliged to continue farming in that farmland for the next 30 years. Since this law fixes land use for a period of 30 years, local governments must observe prudence in designating farmlands as PGL. The process involves close interaction between local governments and landowners for determining which farmlands should be designated as PGL. After the passage of 30 years since the designation of PGL, the landowner has the right to make a claim for the local government to purchase his farmland. In case the landowner waives the claim, the local government decides whether the PGL designation should be renewed for another 30 years. The asset tax structure imposed on farmlands in PGL is far less stringent than taxes on farmlands in ADU (the tax authority assesses taxes for farmlands in PGL based on their earning capacity for agricultural purpose). However, farmlands in PGL are, in principle, prohibited from conversion for non-agricultural purposes.

CPL stipulates that development plans should be approved for UCA only if there are rational reasons for not including those plans under ADU. Furthermore, it should be ensured that the plans do not prompt other development plans under the UCA umbrella. Development Investigation Committees established in every prefecture, ordinance-designated city, nucleated city, and special city, are responsible for ascertaining whether a particular plan qualifies for approval.

In addition to the MLIT zoning regulation of ADU and UCA, MAFF also has its own zoning regulation based on LCAPA. Under this system of regulation, municipal governments designate zoning of Exclusively Agricultural Area (EAA) for provision of preferential treatment entailing agricultural subsidies and tax reduction. In EAA, farmlands are prohibited from being converted. EAA comprises nearly 80% of total farmland area in Japan. Please note that while farmlands under ADU are not included in EAA, majority of farmlands covered by CPA is included in EAA.

Municipal governments revise EAA zoning as necessary. According to MAFF guidelines, every municipal government should incorporate EAA zoning plans in its ten-year plan and should not change the zoning system introduced for at least five years. However, this guideline is only recommendatory in nature and is not legally enforceable. As a result, majority of municipal governments do not observe strict adherence to this guideline and in actual practice, EAA zoning is frequently revised to entertain requests of farmland owners.

Conversion of farmlands under EAA and ADU for non-agricultural purpose is possible if landowners receive permission based on ALL. When a landowner seeks to convert a farmland area of more than 2.0 hectare, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries is responsible for issuing permission for farmland conversion. The responsibility rests with the prefectural governor in all other cases. ALL classifies farmlands into three categories according to quality of the farmland: Type I (high quality), Type II (medium quality), and Type III (low quality). Type III farmlands should be permitted for conversion unless there are special reasons for not doing so. In the case of EAA zoning, a landowner is aware whether his farmland is in EAA. On the contrary, classification into Types I, II, or III is done only after the landowner submits an application of farmland conversion plan. Farmlands of Types I and II should be ideally protected from farmland conversion. However, if the competent authority recognizes that the farmland conversion plan would potentially benefit the local community and there are no suitable alternatives available under Type III or both Types II and III, permission for conversion of Type II or Type I farmland may be issued.

As can be seen in Figure 1, farmland owners receive substantial capital gains from farmland conversion. The expectation of future opportunities for farmland conversion triggers a rise in farmland prices much higher than their earning capacity for farming. High prices prevail even in cases where farmlands are traded between farmers for agricultural purpose.

Although there are no official statistics on farmer revenues from farmland conversions, this study has estimated it based on various data sources (Godo, Y., “The Puzzle of Small Farming in Japan,” Pacific Economic Papers, No 365, 2007). The results are shown in Table 1. As can be seen, revenue from farmland conversions is nearly 40% of the total value of farm products even in non-metropolitan areas. Since farmers obtained (or inherited) their farmlands at a very low cost, this revenue can be considered a clear profit. Even rice production, Japan’s most important crop, shares only one-fourth of the total value of farm products. Thus, Table 1 shows that capital gains from farmland conversions are larger than profits made from crop production.

Additionally, Table 1 presents the downward trend in capital gains from farmland conversions over the past 15 years. This reflects the reduced rate of public constructions and large-scale development plans after the collapse of the “bubble” in the early 1990s. However, there is evidence that illegal farmland conversions have increased during the past 15 years. Since data in Table 1 pertains to legal farmland conversions, in real practice, capital gains may not have decreased over this period.

Date submitted: October 5, 2013

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: October 8, 2013