ABSTRACT

The 2026 Employment for Skill Development Program, Japan’s new program for the admission of foreign laborers, is expected to bring the legal status of foreign laborers into alignment with global standards. The program provides for special, favorable treatment of foreign nationals who are engaged in seasonal labor on Japanese farms. These provisions reflect the severe labor shortage in the Japanese agricultural sector and are expected to meet the increasing demand for and dependence on foreign labor.

Keywords: human rights, seasonal labor, Specified Skilled Worker, Technical Intern Training Program

INTRODUCTION

Japanese factories and farms have long accepted, de facto, foreign agricultural laborers as “technical intern trainees” under the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). However, the TITP does not secure the living and working conditions of technical intern trainees. In 2024, the Japanese government announced the replacement of the TITP with the Employment for Skill Development Program (ESDP), which is expected to go into effect in 2026. This article addresses two questions by reviewing Japan’s history of accepting foreign agricultural labor: What provisions for livelihood and working conditions does the ESDP provide to foreign labor? How will this revision affect Japan’s agricultural sector?

CURRENT SYSTEM FOR ACCEPTING FOREIGN LABOR

The author has already explained the current system of Japan’s foreign laborer policy in the FFTC-AP article titled “Japan’s New Policy on Foreign Laborers and Its Impact on the Agricultural Industry” in 2019. In understanding the Japanese government’s purposes of establishment of ESDP, it is necessary for readers to follow the historical sequence of Japan’s foreign laborer policy. Thus, this section provides a digest of the author’s previous article with updated information.

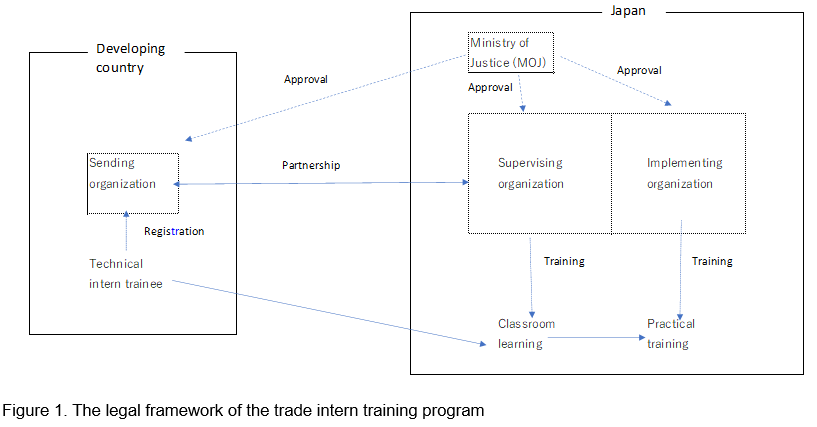

The TITP was established in 1993 and has undergone several revisions since then. The basic structure of the TITP, as it is currently in effect, was established in 2011 (see Figure 1).1 Under this system, a foreign national seeking to reside in Japan as a technical intern trainee must first register as a regular member of a “sending” organization in their country, which, in turn, arranges a “supervising” and an “implementing” organization in Japan. Each technical intern trainee submits their technical intern training plan (jointly signed by their sending, supervising, and implementing organizations) to the Ministry of Justice upon entering Japan. After entering Japan, the technical intern trainee attends classroom learning at the supervising organization, followed by practical training at the implementing organization. By registering themselves as implementing organizations, Japanese factories and farms receive foreign labor as technical intern trainees.

In the first year of the TITP, technical intern trainees are granted visa status as Technical Intern Trainee Type 1 (TIT Type 1). A foreign national who wants to continue working in Japan as a technical intern trainee for more than one year must upgrade their visa status from TIT Type I to TIT Type 2 at the end of their first year of the TITP. This upgrade has three requirements: (i) the technical intern trainee has already acquired technical skills that are equivalent to the Basic 2-Level of the National Technical Skill Test; (ii) the living conditions and work performance of the technical intern trainee are satisfactory; and (iii) the implementing organization that is responsible for the technical intern trainee’s training has an appropriate plan for further training. The TIT Type 2 visa status is valid for two years and non-renewable.

In 2017, the Japanese government established the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT), whose mandate is to review the performance of supervising and implementing organizations. If both the supervising and implementation organizations receive an “excellent” evaluation, the technical intern trainees under them may upgrade their visa status from TIT Type 2 to TIT Type 3, a new visa status valid for two years and non-renewable. This new revision allows technical intern trainees to legally stay in Japan for a maximum of five years (i.e., one year as TIT Type 1, two years as TIT Type 2, and another two years as TIT Type 3).

It is difficult for technical intern trainees to change their implementation organization during the TITP period, thereby weakening their position within the organization. Consider a case in which a technical intern trainee receives poor treatment by their implementation organization. If he or she reports the poor treatment to an authority, such as the Labor Standards Inspection Office, his or her technical intern training plan is automatically canceled, which will force him or her to immediately return to his or her country of nationality. Thus, technical intern trainees tend to be quiet, even if their living and/or working conditions are unsatisfactory. This phenomenon may compromise Japan’s obligation to protect the human rights of foreign nationals and has attracted criticism from international actors.

In response to this criticism, the Japanese government introduced a new visa category, the Specified Skilled Worker (SSW). Individuals holding this visa status are referred to as “specified skilled workers.” While each specified skilled worker may work only in one industrial field, unlike technical intern trainees, they may change workplaces without restriction, provided the workplace remains within the specified industrial field.

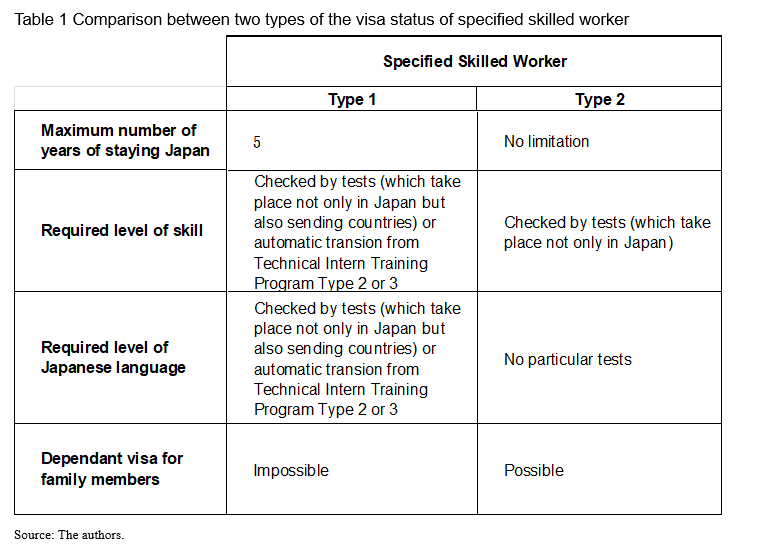

Two types of SSWs exist: SSW Type 1 and SSW Type 2 (see Table 1 for a comparison). The Japanese government has nominated 16 industrial fields open to foreigner labor under SSW Type 1: accommodation; agriculture; automobile repair and maintenance; automobile transportation; aviation; building cleaning management; construction; fishery and aquaculture; food service; forestry; industrial product manufacturing; manufacture of food and beverages; nursing care; railway, shipbuilding, and ship machinery; and the wood industry. Among them, automobile transportation, forestry, nursing care, railway, and wood industries are excluded from SSW Type 2, which covers the remaining 11 industrial fields.

Foreign nationals can obtain the SSW Type 1 visa status through two ways: (i) automatic transition from TIT Type 2 or Type 3 at the completion of the TITP period;2 (ii) take a Japanese language proficiency and working skills test (the content and levels differ according to the 14 industrial fields). Examinations for SSW Type 2 are held only in Japan, and only workers nearing the end of their SSW Type 1 period qualify.3 This way, technical intern trainees can extend their stay in Japan for five years by applying the SSW Type 1. If they upgrade their visa status from SSW Type 1 to SSW Type 2, they can remain in Japan without a time limit.

STATISTICAL REVIEW OF FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL LABOR

Table 2. Foreign nationals in agriculture and forestry as of October 31, 2024a

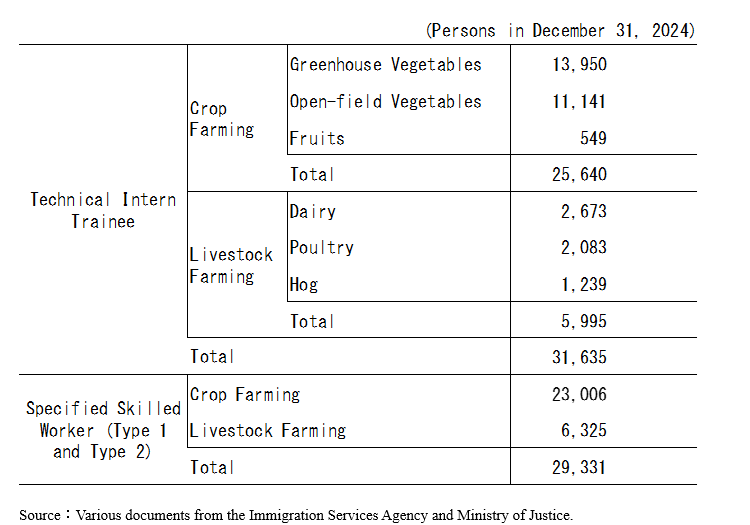

Table 3. Foreign agricultural laborers under the visa statuses of technical intern trainee and specified skilled worker

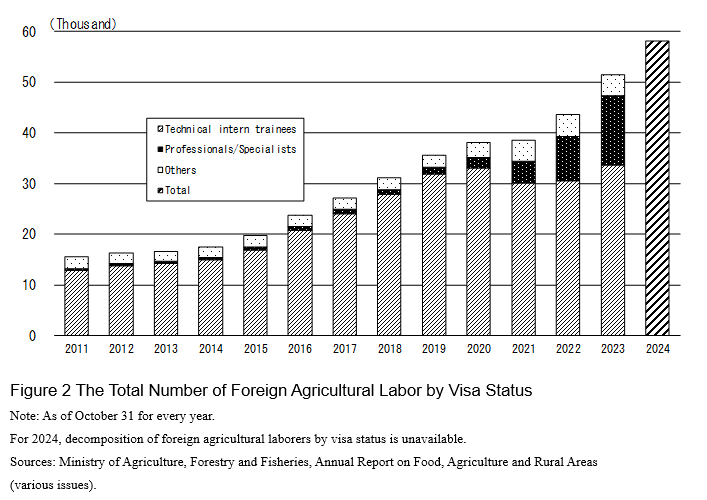

The Japanese government’s major publications refer to the total number of foreign labor, inclusive of all business fields. However, this does not preclude a statistical review of foreign agricultural labor. Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3 present data acquired from various governmental publications (including irregular local government publications).

As Figure 2 shows, the total number of foreign agricultural laborers has continued to increase over the last 14 years, even during the COVID-19 pandemic period. This is partly because foreign factory laborers who lost their jobs were allowed to work on farms as part of the Japanese government’s special measures to relieve the unemployed during the pandemic period.

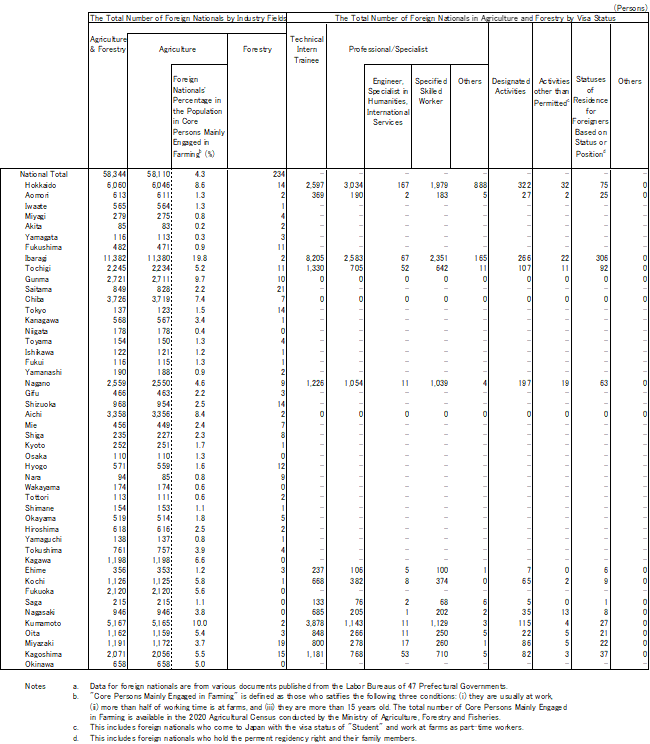

Japan comprises 47 prefectures (including Hokkaido and Tokyo). The Labor Bureaus of 16 prefectures provide data on the total number of foreign nationals employed in the agricultural and forestry industries by visa status (these data are available only for the combined agricultural and forestry industries). The remaining 31 prefectures provide data on the total number of foreign nationals (without visa status). These data are presented in Table 2.

In Japan, the number of agricultural labor is often measured by “core persons mainly engaged in farming” (CPMEF), which is defined as those who satisfy all of the following three conditions: (i) they are usually at work (not in school or housework), (ii) more than half of their working time is at farms, and (iii) they are older than 15 years of age. The total number of CPMEF is one of the core items in Japan’s Agricultural Censuses, which are conducted every five years under the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Based on the 2020 Agricultural Census results, the third column of Table 1 presents the percentage of foreign agricultural labor in the CPMEF. The percentages differed significantly between prefectures.

What is the primary reason for this discrepancy? Table 3 provides answers to this question. The overwhelming majority of foreign agricultural laborers engage in crop farming. Crop farming is particularly common in Hokkaido, Ibaraki, Gunma, Aichi, and Kumamoto. The percentage of foreign agricultural labor in CPMEF is also high in these five prefectures. The National Chamber of Agriculture provides data on the total number of successful and unsuccessful applicants of SSW tests for agriculture. From 2019 to 2024, 29,157 foreign nationals obtained the SSW Type 1 status in agriculture: 22,859 for crop farming and 6,298 for livestock farming. Among them, 15 and 972 were transitions from TITP, and 13,185 were transitions that passed the SSW Type 1 tests. The percentage of successful applicants for the SSW Type 1 test in the agricultural field was 88.7%. This ratio is believed to be much higher than that in non-agricultural industrial fields. It is not uncommon for those holding SSW Type I visa status to change their visa status during their stay in Japan. This implies that some foreign nationals apply for SSW Type 1 in agriculture to enter Japan and then seek better jobs outside agriculture once they arrive.

When the SSW visa was established in April 2019, agriculture was listed only as SSW Type 1. By 2023, agriculture was classified as an SSW Type 2 industrial sector. In 2023 and 2024, tests for SSW Type 2 for agriculture were conducted six times. Two of the 62 foreign nationals with SSW Type 1 applied for these tests. A total of 738 applicants passed the test: 511 in crop farming and 227 in livestock farming, yielding a 35.8% success rate for SSW Type 2 applicants in agriculture.

NEW SYSTEM FOR ACCEPTING FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL LABOR

In the official explanation from the Japanese government, the TITP aims to promote international cooperation through skill transfer. In reality, technical intern trainees have been treated as de facto manual laborers in workplaces (including farms), which has attracted criticism from human rights experts. In 2024, the Japanese government announced that it would replace the TITP with the ESDP by 2026.

The government declared that the ESDP was established to develop and secure human resources in industrial fields experiencing labor shortages, and to develop human resources with SSW Type 1-level skills through three-year employment provisions. Industrial fields that accept foreign nationals under the ESDP are referred to as “ESD industrial fields.” As of 2025, the government has designated the following 16 ESD industrial fields: agriculture, caregiving, restaurant, construction, building cleaning, food processing, hotel, foundry, ship building, fishery, industrial machinery assembly, automobile maintenance, electronic device assembly, aviation-related services, motor truck transportation, railway, forestry, and wood industry. Foreign nationals under the ESDP are referred to as “skill development employees.” Before receiving the ESDP, foreign nationals must register with a sending organization in their country of nationality (sending governments are required to sign a Memorandum of Cooperation with the Japanese government). Employers of employees engaged in skill development are called “accepting” organizations. Special organizations that encourage foreign nationals to accept organizations are called “Employment-for-Skill Development Organizations” (ESDOs). These ESDOs are required to prepare a three-year-long “Employment for Skill Development” plan for each skill-development employee and monitor whether the plan is adequately implemented.

If a skill development employee passes (i) the basic grade of the Trade Skill Test and (ii) the Japanese language proficiency test (the required level differs according to the industrial field), he or she obtains the freedom to change his or her employer in his or her industrial field. Accordingly, competition among employers to hire foreign nationals is expected to increase under the ESDP, thereby improving the working conditions (including wage rates) of foreign nationals.

If a skill development employee passes (i) Grade 9 of the Trade Skill Test or SSW Type 1 Equivalent Test and (ii) A2 or higher level of Japanese language proficiency test, he or she can obtain the SSW Type 1 visa. Even if they fail to pass these two types of tests, they are allowed to stay for up to one year additionally in order to retake the tests.

Foreign nationals are employed as seasonal labor in some types of farming. Since they are not allowed to repeat the TITP once they return to their country of nationality, employers of foreign labor for seasonal jobs only need to recruit different technical intern trainees every year. This imposes a heavy burden on employers. The ESDP provides a solution to these problems: temporary employment agencies are permitted to employ foreign agricultural labor and assign them to different farms at different times (busy seasons vary by crop and/or type of farming). This enables foreign agricultural laborers to remain in Japan for up to three years by changing employers.

CONCLUSION

Japan is now at the dawn of aggressive recruitment of foreign labor. By replacing the TITP with the ESDP, the Japanese government aims to secure a legal position for foreign labor that is at part with global standards, specifically allowing special treatment of workers in the agricultural sector. In short, seasonal labor is permitted in agriculture as an exception under the ESDP in response to the critical labor shortage in this sector. Unlike the TITP, the ESDP permits foreign nationals to change employers. This freedom will stimulate competition among Japanese farms to maintain good foreign agricultural labor, given the importance of labor management for sustainable farming.

Footnotes

1 For years, the government has held the principle that unskilled foreign labor should not be allowed to work in Japan—a principle that reflects Japanese citizens’ anxiety that foreign labor may deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the community’s social order. However, the rapid urbanization in Japan has led to a severe shortage of workers willing to do strenuous manual labor. In 1989, the government created the Industrial Training Program (ITP) to accept unskilled foreign labor as “trainees”; however, these trainees de facto labor and their work was legally treated as part of their training, placing them outside the protections of the Labor Standard Act. Human right groups both inside and outside Japan severely criticized this system as exploitation of foreign nationals. In 1993, the Japanese government established a new system, called the TITP, whereby trainees who completed a one-year training program in Japan could continue working at the same workplace for an additional two years as “technical intern trainees.” Unlike earlier trainees, these technical intern trainees were recognized as laborers whose welfare is protected by the Labor Standard Act. In 2011, Japan abolished the ITP and introduced a new program to accept foreign laborers as technical intern trainees from the first year of their entry into Japan, thereby establishing the TIT Type 1 visa.

2. Technical intern trainees can upgrade their visa status to SSW Type I without any examination of their industrial skills and Japanese language ability as long as the industrial field is the same as their TITP and they complete their technical intern training plan as scheduled.

3. Those who failed the examinations to upgrade their visa status from SSW Type 1 to SSW Type 2 are allowed to extend their visa status to SSW Type 1 for one year to retake the SSW Type 2 examinations in the following year.

Employment for Skill Development Program: A Global Labor Standard for Foreign Agricultural Workers in Japan

ABSTRACT

The 2026 Employment for Skill Development Program, Japan’s new program for the admission of foreign laborers, is expected to bring the legal status of foreign laborers into alignment with global standards. The program provides for special, favorable treatment of foreign nationals who are engaged in seasonal labor on Japanese farms. These provisions reflect the severe labor shortage in the Japanese agricultural sector and are expected to meet the increasing demand for and dependence on foreign labor.

Keywords: human rights, seasonal labor, Specified Skilled Worker, Technical Intern Training Program

INTRODUCTION

Japanese factories and farms have long accepted, de facto, foreign agricultural laborers as “technical intern trainees” under the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). However, the TITP does not secure the living and working conditions of technical intern trainees. In 2024, the Japanese government announced the replacement of the TITP with the Employment for Skill Development Program (ESDP), which is expected to go into effect in 2026. This article addresses two questions by reviewing Japan’s history of accepting foreign agricultural labor: What provisions for livelihood and working conditions does the ESDP provide to foreign labor? How will this revision affect Japan’s agricultural sector?

CURRENT SYSTEM FOR ACCEPTING FOREIGN LABOR

The author has already explained the current system of Japan’s foreign laborer policy in the FFTC-AP article titled “Japan’s New Policy on Foreign Laborers and Its Impact on the Agricultural Industry” in 2019. In understanding the Japanese government’s purposes of establishment of ESDP, it is necessary for readers to follow the historical sequence of Japan’s foreign laborer policy. Thus, this section provides a digest of the author’s previous article with updated information.

The TITP was established in 1993 and has undergone several revisions since then. The basic structure of the TITP, as it is currently in effect, was established in 2011 (see Figure 1).1 Under this system, a foreign national seeking to reside in Japan as a technical intern trainee must first register as a regular member of a “sending” organization in their country, which, in turn, arranges a “supervising” and an “implementing” organization in Japan. Each technical intern trainee submits their technical intern training plan (jointly signed by their sending, supervising, and implementing organizations) to the Ministry of Justice upon entering Japan. After entering Japan, the technical intern trainee attends classroom learning at the supervising organization, followed by practical training at the implementing organization. By registering themselves as implementing organizations, Japanese factories and farms receive foreign labor as technical intern trainees.

In the first year of the TITP, technical intern trainees are granted visa status as Technical Intern Trainee Type 1 (TIT Type 1). A foreign national who wants to continue working in Japan as a technical intern trainee for more than one year must upgrade their visa status from TIT Type I to TIT Type 2 at the end of their first year of the TITP. This upgrade has three requirements: (i) the technical intern trainee has already acquired technical skills that are equivalent to the Basic 2-Level of the National Technical Skill Test; (ii) the living conditions and work performance of the technical intern trainee are satisfactory; and (iii) the implementing organization that is responsible for the technical intern trainee’s training has an appropriate plan for further training. The TIT Type 2 visa status is valid for two years and non-renewable.

In 2017, the Japanese government established the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT), whose mandate is to review the performance of supervising and implementing organizations. If both the supervising and implementation organizations receive an “excellent” evaluation, the technical intern trainees under them may upgrade their visa status from TIT Type 2 to TIT Type 3, a new visa status valid for two years and non-renewable. This new revision allows technical intern trainees to legally stay in Japan for a maximum of five years (i.e., one year as TIT Type 1, two years as TIT Type 2, and another two years as TIT Type 3).

It is difficult for technical intern trainees to change their implementation organization during the TITP period, thereby weakening their position within the organization. Consider a case in which a technical intern trainee receives poor treatment by their implementation organization. If he or she reports the poor treatment to an authority, such as the Labor Standards Inspection Office, his or her technical intern training plan is automatically canceled, which will force him or her to immediately return to his or her country of nationality. Thus, technical intern trainees tend to be quiet, even if their living and/or working conditions are unsatisfactory. This phenomenon may compromise Japan’s obligation to protect the human rights of foreign nationals and has attracted criticism from international actors.

In response to this criticism, the Japanese government introduced a new visa category, the Specified Skilled Worker (SSW). Individuals holding this visa status are referred to as “specified skilled workers.” While each specified skilled worker may work only in one industrial field, unlike technical intern trainees, they may change workplaces without restriction, provided the workplace remains within the specified industrial field.

Two types of SSWs exist: SSW Type 1 and SSW Type 2 (see Table 1 for a comparison). The Japanese government has nominated 16 industrial fields open to foreigner labor under SSW Type 1: accommodation; agriculture; automobile repair and maintenance; automobile transportation; aviation; building cleaning management; construction; fishery and aquaculture; food service; forestry; industrial product manufacturing; manufacture of food and beverages; nursing care; railway, shipbuilding, and ship machinery; and the wood industry. Among them, automobile transportation, forestry, nursing care, railway, and wood industries are excluded from SSW Type 2, which covers the remaining 11 industrial fields.

Foreign nationals can obtain the SSW Type 1 visa status through two ways: (i) automatic transition from TIT Type 2 or Type 3 at the completion of the TITP period;2 (ii) take a Japanese language proficiency and working skills test (the content and levels differ according to the 14 industrial fields). Examinations for SSW Type 2 are held only in Japan, and only workers nearing the end of their SSW Type 1 period qualify.3 This way, technical intern trainees can extend their stay in Japan for five years by applying the SSW Type 1. If they upgrade their visa status from SSW Type 1 to SSW Type 2, they can remain in Japan without a time limit.

STATISTICAL REVIEW OF FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL LABOR

Table 2. Foreign nationals in agriculture and forestry as of October 31, 2024a

Table 3. Foreign agricultural laborers under the visa statuses of technical intern trainee and specified skilled worker

The Japanese government’s major publications refer to the total number of foreign labor, inclusive of all business fields. However, this does not preclude a statistical review of foreign agricultural labor. Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3 present data acquired from various governmental publications (including irregular local government publications).

As Figure 2 shows, the total number of foreign agricultural laborers has continued to increase over the last 14 years, even during the COVID-19 pandemic period. This is partly because foreign factory laborers who lost their jobs were allowed to work on farms as part of the Japanese government’s special measures to relieve the unemployed during the pandemic period.

Japan comprises 47 prefectures (including Hokkaido and Tokyo). The Labor Bureaus of 16 prefectures provide data on the total number of foreign nationals employed in the agricultural and forestry industries by visa status (these data are available only for the combined agricultural and forestry industries). The remaining 31 prefectures provide data on the total number of foreign nationals (without visa status). These data are presented in Table 2.

In Japan, the number of agricultural labor is often measured by “core persons mainly engaged in farming” (CPMEF), which is defined as those who satisfy all of the following three conditions: (i) they are usually at work (not in school or housework), (ii) more than half of their working time is at farms, and (iii) they are older than 15 years of age. The total number of CPMEF is one of the core items in Japan’s Agricultural Censuses, which are conducted every five years under the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Based on the 2020 Agricultural Census results, the third column of Table 1 presents the percentage of foreign agricultural labor in the CPMEF. The percentages differed significantly between prefectures.

What is the primary reason for this discrepancy? Table 3 provides answers to this question. The overwhelming majority of foreign agricultural laborers engage in crop farming. Crop farming is particularly common in Hokkaido, Ibaraki, Gunma, Aichi, and Kumamoto. The percentage of foreign agricultural labor in CPMEF is also high in these five prefectures. The National Chamber of Agriculture provides data on the total number of successful and unsuccessful applicants of SSW tests for agriculture. From 2019 to 2024, 29,157 foreign nationals obtained the SSW Type 1 status in agriculture: 22,859 for crop farming and 6,298 for livestock farming. Among them, 15 and 972 were transitions from TITP, and 13,185 were transitions that passed the SSW Type 1 tests. The percentage of successful applicants for the SSW Type 1 test in the agricultural field was 88.7%. This ratio is believed to be much higher than that in non-agricultural industrial fields. It is not uncommon for those holding SSW Type I visa status to change their visa status during their stay in Japan. This implies that some foreign nationals apply for SSW Type 1 in agriculture to enter Japan and then seek better jobs outside agriculture once they arrive.

When the SSW visa was established in April 2019, agriculture was listed only as SSW Type 1. By 2023, agriculture was classified as an SSW Type 2 industrial sector. In 2023 and 2024, tests for SSW Type 2 for agriculture were conducted six times. Two of the 62 foreign nationals with SSW Type 1 applied for these tests. A total of 738 applicants passed the test: 511 in crop farming and 227 in livestock farming, yielding a 35.8% success rate for SSW Type 2 applicants in agriculture.

NEW SYSTEM FOR ACCEPTING FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL LABOR

In the official explanation from the Japanese government, the TITP aims to promote international cooperation through skill transfer. In reality, technical intern trainees have been treated as de facto manual laborers in workplaces (including farms), which has attracted criticism from human rights experts. In 2024, the Japanese government announced that it would replace the TITP with the ESDP by 2026.

The government declared that the ESDP was established to develop and secure human resources in industrial fields experiencing labor shortages, and to develop human resources with SSW Type 1-level skills through three-year employment provisions. Industrial fields that accept foreign nationals under the ESDP are referred to as “ESD industrial fields.” As of 2025, the government has designated the following 16 ESD industrial fields: agriculture, caregiving, restaurant, construction, building cleaning, food processing, hotel, foundry, ship building, fishery, industrial machinery assembly, automobile maintenance, electronic device assembly, aviation-related services, motor truck transportation, railway, forestry, and wood industry. Foreign nationals under the ESDP are referred to as “skill development employees.” Before receiving the ESDP, foreign nationals must register with a sending organization in their country of nationality (sending governments are required to sign a Memorandum of Cooperation with the Japanese government). Employers of employees engaged in skill development are called “accepting” organizations. Special organizations that encourage foreign nationals to accept organizations are called “Employment-for-Skill Development Organizations” (ESDOs). These ESDOs are required to prepare a three-year-long “Employment for Skill Development” plan for each skill-development employee and monitor whether the plan is adequately implemented.

If a skill development employee passes (i) the basic grade of the Trade Skill Test and (ii) the Japanese language proficiency test (the required level differs according to the industrial field), he or she obtains the freedom to change his or her employer in his or her industrial field. Accordingly, competition among employers to hire foreign nationals is expected to increase under the ESDP, thereby improving the working conditions (including wage rates) of foreign nationals.

If a skill development employee passes (i) Grade 9 of the Trade Skill Test or SSW Type 1 Equivalent Test and (ii) A2 or higher level of Japanese language proficiency test, he or she can obtain the SSW Type 1 visa. Even if they fail to pass these two types of tests, they are allowed to stay for up to one year additionally in order to retake the tests.

Foreign nationals are employed as seasonal labor in some types of farming. Since they are not allowed to repeat the TITP once they return to their country of nationality, employers of foreign labor for seasonal jobs only need to recruit different technical intern trainees every year. This imposes a heavy burden on employers. The ESDP provides a solution to these problems: temporary employment agencies are permitted to employ foreign agricultural labor and assign them to different farms at different times (busy seasons vary by crop and/or type of farming). This enables foreign agricultural laborers to remain in Japan for up to three years by changing employers.

CONCLUSION

Japan is now at the dawn of aggressive recruitment of foreign labor. By replacing the TITP with the ESDP, the Japanese government aims to secure a legal position for foreign labor that is at part with global standards, specifically allowing special treatment of workers in the agricultural sector. In short, seasonal labor is permitted in agriculture as an exception under the ESDP in response to the critical labor shortage in this sector. Unlike the TITP, the ESDP permits foreign nationals to change employers. This freedom will stimulate competition among Japanese farms to maintain good foreign agricultural labor, given the importance of labor management for sustainable farming.

Footnotes

1 For years, the government has held the principle that unskilled foreign labor should not be allowed to work in Japan—a principle that reflects Japanese citizens’ anxiety that foreign labor may deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the community’s social order. However, the rapid urbanization in Japan has led to a severe shortage of workers willing to do strenuous manual labor. In 1989, the government created the Industrial Training Program (ITP) to accept unskilled foreign labor as “trainees”; however, these trainees de facto labor and their work was legally treated as part of their training, placing them outside the protections of the Labor Standard Act. Human right groups both inside and outside Japan severely criticized this system as exploitation of foreign nationals. In 1993, the Japanese government established a new system, called the TITP, whereby trainees who completed a one-year training program in Japan could continue working at the same workplace for an additional two years as “technical intern trainees.” Unlike earlier trainees, these technical intern trainees were recognized as laborers whose welfare is protected by the Labor Standard Act. In 2011, Japan abolished the ITP and introduced a new program to accept foreign laborers as technical intern trainees from the first year of their entry into Japan, thereby establishing the TIT Type 1 visa.

2. Technical intern trainees can upgrade their visa status to SSW Type I without any examination of their industrial skills and Japanese language ability as long as the industrial field is the same as their TITP and they complete their technical intern training plan as scheduled.

3. Those who failed the examinations to upgrade their visa status from SSW Type 1 to SSW Type 2 are allowed to extend their visa status to SSW Type 1 for one year to retake the SSW Type 2 examinations in the following year.