ABSTRACT

In Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS), candidate sites, and potential candidate sites, it is important to take into account the characteristics of the area and the characteristics of the goods and services that can be sold in order to conserve the agro-cultural system and promote the area, as well as management measures. For this reason, this study proposes options for agro-cultural system management measures and methods for regional development according to each region's natural and cultural characteristics, the conditions of the actors involved, and the potential for administrative support. Using the concepts of ‘excludability’ and ‘scarcity,’ the paper provides an overview of the management initiatives by entities involved in these initiatives. Further, by classifying the entities into "public" (national and local governments), "non-profit" (NGO or non-profit associations/councils, etc.), and "private" (farmers and citizens, agricultural cooperatives, etc.), we take a look at each of the management approach. The paper’s discussion will be useful for other countries that are considering applying for GIAHS.

Keywords: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS), public goods, management approaches

INTRODUCTION

Traditional rural landscapes and diverse flora and fauna, rural unique cultural, historical agriculture constructs, and traditional technology of agricultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, have been maintained and inherited by ‘the agricultural system’ that is cultured by ‘agri-cultural’ practices where agriculture, biodiversity, and life and history are intertwined. However, region-specific agricultural and cultural systems have been weakened through the modernization of agriculture, the decline and aging of the rural population, and the diversification of lifestyle, and they are on the verge of loss.

While many valuable traditional features and traditional cultural practices of the rural landscapes are rapidly disappearing, Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) was created in 2002 by FAO to recognize and certify agricultural land use systems and the rural landscape that conserve biodiversity and agricultural culture should leave to posterity (FAO, 2006). A feature of GIAHS is that, while the UNESCO World Heritage Site is intended for the protection and preservation of monuments, historic buildings, and memories, GIAHS recognizes the sustainable utilization and conservation of traditional agriculture's "system" to be inherited by the next generation as its purpose. The “system” includes both tangible and intangible things like knowledge and skills.

As of October 2024, 86 systems in 26 countries are certified. While 3 in Africa, 10 in Europe and Central Asia, 7 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 9 in Near East and North Africa being certified, Asia and the Pacific has as many as 57 areas, especially 22 in China, followed by 15 in Japan, 7 in South Korea, and 6 in Iran. For Japan, the Noto area in Ishikawa Prefecture and the Sado region of Niigata Prefecture were certified in June 2011 for the first time. In May 2013, the Kakegawa area in Shizuoka Prefecture, Kunisaki Peninsula Usa in Oita Prefecture, and the Aso area in Kumamoto Prefecture were also certified, followed by 10 sites.

This study, in response to the movement of domestic and overseas over GIAHS, aims to assess the choices of various support policies by both public and non-public entities to support and preserve the agricultural culture system, further connecting the GIAHS designation to regional development. Therefore, this paper provides an overview of the management initiatives by entities involved in these initiatives. Further, by classifying the actors into "public" (national and local governments), "non-profit" (NGO or non-profit associations/councils, etc.), and "private" (farmers and citizens, agricultural cooperatives, etc.), we take a look at each of the management approach. The GIAHS sites used were the ones designated in the early phase of GIAHS between 2002 and 2013 in the Philippines, China, South Korea, and Japan.

CLASSIFICATION OF MANAGEMENT INITIATIVES

In this overview, the term “non-excludability” can be useful to classify management initiatives. 'Exclusiveness' is used to explain an economic concept of “goods.” It refers to the property of a good, such that if a person uses a particular good, the good itself or its services are not available unless they pay the price. On the other hand, agricultural systems, including the GIAHS, are considered public goods. As such, they are available to everyone free of charge, and no one can be excluded from utilizing them (non-excludable). As long as it is freely available and is enjoyed by anyone without any fee, no one is responsible for managing it. Eventually, it causes deterioration of the system or a problem in managing them.

Suppose goods and services originating from the agro-cultural system and applying exclusionary characteristics are supplied. In that case, conservation measures and promotion measures using 'market approaches,' such as differentiation in the sale of agricultural products or entrance fees, are possible. On the other hand, if goods and services with exclusionary characteristics are not provided, the 'non-market approaches,' namely the 'institutional approach' and the 'citizen participation approach,' are mainly applicable. In the former, governments and local authorities are the main actors of the management and use methods such as subsidies and regulation. In the latter, citizens take the lead in forming councils and other organizations to preserve and promote agro-cultural systems. The former is more generally applicable for supporting nationwide uniform initiatives, while the latter is suited to cases where region-specific targets are; however, the reverse cases can be observed in practice. Furthermore, what was initially a citizen participation approach may be combined with a market approach by supplying market goods.

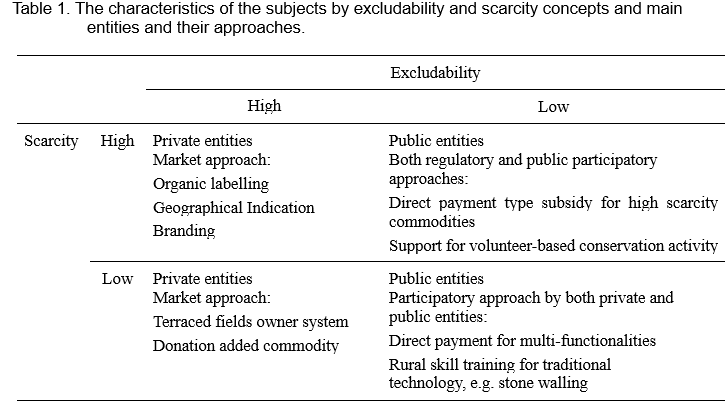

Adding the 'scarcity' perspective of the conservation object/target to this 'excludability' perspective, the following four categories are considered in relation to the conservation direction and related private or public support activities (see Table 1). Scarcity means when the resource or practices concerned are not abundant and rather scares. The subject cannot be easily found in other places or the subject itself is scares. Then, we systematically analyze the present status of GIAHS sites’ management system by actual conservation approaches namely market approach, regulatory approach and participatory approach. By analyzing both management system and regulatory framework determine whether the GIAHS are sustainably managed.

SELECTION OF INITIATIVES WITH CASE STUDIES

This section applies the above concepts and presents examples of GIAHS in practice based on each category.

High excludability and high scarcity

The market approach is effective if agricultural products in GIAHS-certified regions can be sold at a high price. In other words, the consumers are willing to pay higher prices for agricultural products in GIAHS-designated sites as they appreciate the heritage value of the system. In that case, the consumer appreciates services that cannot be enjoyed in other areas and brand products that are famous and available only in the specific area. Thus, the incentive to conserve an agricultural culture system actively emerges among farmers and cooperative organizations.

An example is a rice-fish symbiotic system Qingtian County, Zhejiang, China, with a 1,200-year-old history of production in practice (Min & Zhang, 2020). Before the GIAHS designation in 2005, the sale price was around RMB25 (approximately US$3.13[1]) per kg of fish in 2005. In 2015, the sale price increased to RMB70-80 (approximately US$10.77 to 12.31 in 2015[2]) per kg of fish. The rice was also traded for around RMB2,500 (approximately US$312.5 in 2005) per ton of husked rice before GIAHS designation; the price increased to RMB5,000 (approximately US$769.2 in 2015) per ton of husked rice value. The rice is packed as a gift and sold at a higher value-added price.

Another example is the terraced landscape of Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province (Gu et al., 2012). The terraced rice field landscape itself is less exclusionary as it is generally easily visible to everyone. However, Hani terraced rice fields can be given exclusivity with an observatory in the middle of a cliff with a good view when the terraced rice fields are not easily visible by planting standing trees on the road. The terraced rice fields cannot be seen from the road easily, but only on terraces. By secluding the viewpoint from the observatory, it is possible to impose the entrance fee, and it enables putting a market value to the rice paddy terrace landscape. Further, part of the admission fee income has been redistributed to the farmers for their landscape maintenance activities.

As methods to support and strengthen these management efforts to maintain the quality of the agricultural system, there are "geographical indications," "organic certification," and "other certification or labeling such as fair-trade.” Also, efforts have been made to promote agricultural products in these areas through "public relations" and "branding." This category involves discussions of how to expand the promotion of agricultural and cultural systems that utilize such a market-good approach.

Tea produced by Shizuoka's GIAHS tea grassland farming method is certified in three categories of farmers who practice tea grassland farming according to the ratio of the area of tea grassland they manage to the area of their tea gardens, and tea-related products they sell are labelled with the certification seal (Hidehiro & Yoshinobu, 2014). The high price-forming effect of GIAHS labelling on agricultural products and processed agricultural products with the seal of certification was shown to appear higher for gift-giving than for private use (Kurokawa et al., 2019). Thus, in the case of rare market goods, GIAHS registration is expected to be effective in price formation by storing the value of local agricultural products and processed agricultural products, and by promoting their value and contribution to agricultural culture, particularly for gift products.

Low excludability and high scarcity

Applying excludability to rural biodiversity and landscape is rather challenging as they are considered public goods. Therefore, a non-market approach to the conservation of GIAHS systems should be promoted. In the institutional approach, direct payments are made to the efforts of advanced biodiversity conservation for higher levels of conservation initiatives. One example is the agri-environment payment scheme in the UK, Japan, South Korea, and others (Legg, 2009). Although it is not an example of a GIAHS site, it is a national policy to conserve farmland biodiversities and other multiple functions or ecological services that it provides.

Ecological services, or ecosystem services, means the benefits humans receive from nature and its ecosystems (Daily, 1997). Also, other national governments aggregated regulatory authority for conservation and economic activity for a national park, and the national park committees provide governance, planning, policy, and programs that efficiently conserve the landscape and ecosystems. The introduction of these management initiatives requires financial support, which is inevitably limited to a certain extent depending on the country or area concerned. Still, the selection of initiatives is "subsidies to the landscape component," "volunteers and NPO activities support," and "conservation and economic activity aggregated to regulatory authority." These policy options in this category are worth considering.

As a citizen participatory approach, it includes landscape conservation by the NGOs and volunteers. In addition, it applies the use of citizen volunteers in scenic area conservation and its conservation activities. The volunteers also conserve both biodiversity and landscape in combination with a market approach, where they charge admission to the scenic area. In case of Aso grassland, the grasslands of Aso exist as the result of enormous volcanic activity that occurred long ago coupled with careful conservation and maintenance by the locals. NGO called “the Aso Green Stock” organizes and trains volunteers for grassland burning activities, which are essential for maintaining the grassland ecosystem. They do it by “Noyaki,” the controlled burning, in early spring. This large-scale activity has been ongoing for over 20 years, with approximately 2,000 volunteers participating annually. These volunteers undergo training to understand the risks and techniques involved in grassland burning, ensuring safe and effective management of the grasslands (Takahashi et al., 2017).

High excludability and low scarcity

Because excludability exists, it is possible to promote a market approach. However, despite the high price value of agricultural products in high excludability and high scarcity conditions, scarcity in this category is not high. In this case, an appropriate approach is to select financial resources acquisition toward conservation by the mass sale at a low value-added rate of each agricultural product. In other words, each product’s added value might be slim, however, the mass sale of the product can still acquire the finance necessary for conservation activities, and therefore a broad and shallow support is sought (Nomura & Yabe, 2014). Examples include products with a small environmental donation. Examples include Aeon's prepaid electronic money card of Aso, Kumamoto and the Senmaida owner system of Sado, Niigata.

The first example in this category is the prepaid electronic money card of AEON retail company, a specialist shopping mall developer in Japan. The AEON prepaid electronic money card is a pre-paid, rechargeable card. When you first purchase an AEON card, you can select the area where one wants to donate. Each time you purchase using the card, part of the utilization amount is donated to the fund-raising entity of the area selected. Thus, as a participatory approach, the fund-raising body can approach new customers to select the conservation area card. As the number of consumers with the card increases, the amount of donations that go to the area increases. More than a hundred cards from locals are registered and are supporting local activities, including one of the GIAHS sites for "Aso grassland regeneration fund-raising."

Another example is the Sado Ogura thousand rice terrace Ownership System. It asks consumers to be patrons of a rice-terraced paddy and support the local effort to maintain the rice terrace. In Japan, the rice terrace owner system has grown its popularity. It involves urban dwellers who provide financial and labor support to become owners of rice terraces and at the same time gain experience of being part of production and enjoy the rural environment. The city dwellers and farmers also can communicate with each other to understand the importance of conserving rural landscapes. The financial support is then used for the maintenance and restoration of the landscapes (Saito & Ichikawa, 2014). The selection of other measures in this High excludability and low scarcity category includes "certification system," "public relations," "quality improvement, and quantitative expansion of the production base." The challenge is expanding this approach further with a broad base.

Low excludability and low scarcity

From an ecological point of view or prevention of landslides, for example, sometimes maintenance activities for the agricultural system in the large scale of land area participation become important from the perspective of strengthening the foundation of the system. Important, however, that it is hard to limit the area and it is difficult to limit productivity, and therefore, scarcity of the product produced decreases. One example of the institutional approach is the maintenance support of general biodiversity through direct payment, such as in less favored areas. Such direct payment typically refers to financial assistance provided by governments or organizations to support agricultural activities in regions that face challenges such as poor soil quality, limited access to water, or harsh climatic conditions like hilly areas. These payments are often aimed at ensuring food security, promoting sustainable agriculture, and supporting rural development in areas where farming may be economically unviable without additional support. The choice of initiatives and support ranged from “direct payment system,” “support that strengthens volunteer activities,” and “human resource development” for learning support of traditional techniques. How to expand such initiative efforts can be a critical issue in maintaining the agricultural system's integrity.

One of the interesting cross GIAHS collaborations for human resource development is Ifugao Satoyama Meister Training Program (Buot, 2021). The Ifugao Satoyama Meister Training Program is a human capacity building initiative aimed at the sustainable development and conservation of the Ifugao Rice Terraces. This program was implemented in 2014 by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) through Kanazawa University, in collaboration with the Ifugao State University, University of the Philippines Open University, and the Provincial Government of Ifugao. It is an internaitonal collaboration program that focuses on empowering local stakeholders by providing them with the necessary knowledge and skills for sustainable development through research, seminars, skills training, and field exposures. The program supports numerous research projects, including assessments of the cultural and ecological significance of the Ifugao Rice Terraces. The program has developed through multiple phases, with Phase 2 starting in 2017, which included a twinning initiative with Japan’s Noto’s Satoyama and Satoumi. Currently, Phase 3 has been launched in 2021 to continue ongoing research and capacity building efforts.

SYSTEMS AND CONDITIONS FOR IMPLEMENTING SUPPORT MEASURES

This paper organizes approaches for agro-cultural conservation based on exclusiveness and scarcity. However, first, a means of assessing 'exclusiveness' and 'scarcity' and a system for implementing the considered approaches are needed. From this perspective, the selection of indicators for the assessment of agri-cultural diversity and the cooperation system between the relevant institutions are addressed.

Indicator for assessing the level and quality of agri-‘cultural’ diversity

Indicators are selected to facilitate a simple assessment of the level and quality of agri-‘cultural’ diversity within the agro-cultural system. By following changes in these indicators, the status of diversity and the effectiveness of specific conservation or management activities can then be conveniently assessed. Conservation activities are implemented as a menu of initiatives within the management, institutional, and public participation approaches financed by the market approach.

Institutionalization

A system is necessary for the market, institutional, and citizen participatory approaches to be implemented in an integrated and effective manner. For example, National Parks in Japan incorporate a wide range of relevant agencies, including local authorities, public bodies, and private organizations. These bodies are not merely named there but have their own areas of responsibility and tasks. The government should actively seek partnerships with NPOs, citizens' groups involved in conservation, and even private companies. It is also necessary to bring in volunteers from outside rather than managing within the registered area with a limited number of civil servants and other staff. If the relevant organizations lack the know-how to attract volunteers, they could reinforce this weakness by adding organizations that specialize in such activities as partners.

CONCLUSION

As described above, it is important for Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems and candidate sites, or potential candidate sites, to take into account the characteristics of the area and the characteristics of the goods and services that can be sold in order to conserve and manage the agro-cultural system and promote the area, as well as support measures. Therefore, this study proposed options for agro-cultural system conservation measures and regional development methods according to each region's natural and cultural characteristics, the actors' conditions, and the potential for administrative support.

REFERENCES

Buot, I. E. (2021). Its Organic Agriculture Practices, Current Challenges, and Initiatives. Journal of Nature Studies, 20(2), 22–32.

Daily, G. C. (1997). Introduction: what are ecosystem services. Nature’s services: Societal dependence on natural ecosystems, 1(1).

FAO. (2006). Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) -A Heritage for the Future-. www.fao.org/icatalog/inter-e.htm

Gu, H., Jiao, Y., & Liang, L. (2012). Strengthening the socio-ecological resilience of forest-dependent communities: The case of the Hani Rice Terraces in Yunnan, China. Forest Policy and Economics, 22, 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2012.04.004

Hidehiro, I., & Yoshinobu, K. (2014). Assessment of GIAHS in Shizuoka: The Traditional Tea-Grass Integrated System. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 5(4), 398–401. https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2014.04.017

Hisako, N., & Mitsuyasu, Y. (2014). Private Provision of Environmental Public Goods: A Pilot Program for Agricultural Heritage Conservation. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 5(4), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2014.04.009

Kurokawa, T., Yabe, M., Nomura, H., & Takahashi, Y. (2019). Consumer Valuation of Green Tea Leaves Produced through Chagusaba Farming: A Case of GIAHS in Shizuoka. Journal of Rural Problems, 55(2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.7310/arfe.55.81

Legg, W. (2009). Payments for agri-environmental services: an OECD perspective. In New Perspectives on Agri-environmental Policies (pp. 55-65). Routledge.

Min, Q., & Zhang, B. (2020). Research progress in the conservation and development of china-nationally important agricultural heritage systems (China-NIAHS). Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010126

Saito, O., & Ichikawa, K. (2014). Socio-ecological Systems in Paddy Dominated Landscapes in Asian Monsoon. In Nishikawa Usio & Miyashita Tadashi (Eds.), Social-ecological Restoration in Paddy-Dominated Landscapes: Springer, Tokyo (pp. 1–311).

Takahashi, Y., Neef, A., & Yokogawa, H. (2017). Conservation and Restoration of traditional grasslands in the Mount Aso Region of Kyushu, Japan -The Role of collaborative management and public policy support. In M. Cairns (Ed.), Shifting cultivation policies: Balancing environmental and social sustainability. CABI. (pp. 1–1057). CABI. https://cabidigitallibrary.org

[1] 8 RMB = about 1 US dollar in 2005

[2] 6.5 RMB = about 1 US dollar in 2015

Framework for the Management Initiatives of the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems

ABSTRACT

In Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS), candidate sites, and potential candidate sites, it is important to take into account the characteristics of the area and the characteristics of the goods and services that can be sold in order to conserve the agro-cultural system and promote the area, as well as management measures. For this reason, this study proposes options for agro-cultural system management measures and methods for regional development according to each region's natural and cultural characteristics, the conditions of the actors involved, and the potential for administrative support. Using the concepts of ‘excludability’ and ‘scarcity,’ the paper provides an overview of the management initiatives by entities involved in these initiatives. Further, by classifying the entities into "public" (national and local governments), "non-profit" (NGO or non-profit associations/councils, etc.), and "private" (farmers and citizens, agricultural cooperatives, etc.), we take a look at each of the management approach. The paper’s discussion will be useful for other countries that are considering applying for GIAHS.

Keywords: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS), public goods, management approaches

INTRODUCTION

Traditional rural landscapes and diverse flora and fauna, rural unique cultural, historical agriculture constructs, and traditional technology of agricultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, have been maintained and inherited by ‘the agricultural system’ that is cultured by ‘agri-cultural’ practices where agriculture, biodiversity, and life and history are intertwined. However, region-specific agricultural and cultural systems have been weakened through the modernization of agriculture, the decline and aging of the rural population, and the diversification of lifestyle, and they are on the verge of loss.

While many valuable traditional features and traditional cultural practices of the rural landscapes are rapidly disappearing, Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) was created in 2002 by FAO to recognize and certify agricultural land use systems and the rural landscape that conserve biodiversity and agricultural culture should leave to posterity (FAO, 2006). A feature of GIAHS is that, while the UNESCO World Heritage Site is intended for the protection and preservation of monuments, historic buildings, and memories, GIAHS recognizes the sustainable utilization and conservation of traditional agriculture's "system" to be inherited by the next generation as its purpose. The “system” includes both tangible and intangible things like knowledge and skills.

As of October 2024, 86 systems in 26 countries are certified. While 3 in Africa, 10 in Europe and Central Asia, 7 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 9 in Near East and North Africa being certified, Asia and the Pacific has as many as 57 areas, especially 22 in China, followed by 15 in Japan, 7 in South Korea, and 6 in Iran. For Japan, the Noto area in Ishikawa Prefecture and the Sado region of Niigata Prefecture were certified in June 2011 for the first time. In May 2013, the Kakegawa area in Shizuoka Prefecture, Kunisaki Peninsula Usa in Oita Prefecture, and the Aso area in Kumamoto Prefecture were also certified, followed by 10 sites.

This study, in response to the movement of domestic and overseas over GIAHS, aims to assess the choices of various support policies by both public and non-public entities to support and preserve the agricultural culture system, further connecting the GIAHS designation to regional development. Therefore, this paper provides an overview of the management initiatives by entities involved in these initiatives. Further, by classifying the actors into "public" (national and local governments), "non-profit" (NGO or non-profit associations/councils, etc.), and "private" (farmers and citizens, agricultural cooperatives, etc.), we take a look at each of the management approach. The GIAHS sites used were the ones designated in the early phase of GIAHS between 2002 and 2013 in the Philippines, China, South Korea, and Japan.

CLASSIFICATION OF MANAGEMENT INITIATIVES

In this overview, the term “non-excludability” can be useful to classify management initiatives. 'Exclusiveness' is used to explain an economic concept of “goods.” It refers to the property of a good, such that if a person uses a particular good, the good itself or its services are not available unless they pay the price. On the other hand, agricultural systems, including the GIAHS, are considered public goods. As such, they are available to everyone free of charge, and no one can be excluded from utilizing them (non-excludable). As long as it is freely available and is enjoyed by anyone without any fee, no one is responsible for managing it. Eventually, it causes deterioration of the system or a problem in managing them.

Suppose goods and services originating from the agro-cultural system and applying exclusionary characteristics are supplied. In that case, conservation measures and promotion measures using 'market approaches,' such as differentiation in the sale of agricultural products or entrance fees, are possible. On the other hand, if goods and services with exclusionary characteristics are not provided, the 'non-market approaches,' namely the 'institutional approach' and the 'citizen participation approach,' are mainly applicable. In the former, governments and local authorities are the main actors of the management and use methods such as subsidies and regulation. In the latter, citizens take the lead in forming councils and other organizations to preserve and promote agro-cultural systems. The former is more generally applicable for supporting nationwide uniform initiatives, while the latter is suited to cases where region-specific targets are; however, the reverse cases can be observed in practice. Furthermore, what was initially a citizen participation approach may be combined with a market approach by supplying market goods.

Adding the 'scarcity' perspective of the conservation object/target to this 'excludability' perspective, the following four categories are considered in relation to the conservation direction and related private or public support activities (see Table 1). Scarcity means when the resource or practices concerned are not abundant and rather scares. The subject cannot be easily found in other places or the subject itself is scares. Then, we systematically analyze the present status of GIAHS sites’ management system by actual conservation approaches namely market approach, regulatory approach and participatory approach. By analyzing both management system and regulatory framework determine whether the GIAHS are sustainably managed.

SELECTION OF INITIATIVES WITH CASE STUDIES

This section applies the above concepts and presents examples of GIAHS in practice based on each category.

High excludability and high scarcity

The market approach is effective if agricultural products in GIAHS-certified regions can be sold at a high price. In other words, the consumers are willing to pay higher prices for agricultural products in GIAHS-designated sites as they appreciate the heritage value of the system. In that case, the consumer appreciates services that cannot be enjoyed in other areas and brand products that are famous and available only in the specific area. Thus, the incentive to conserve an agricultural culture system actively emerges among farmers and cooperative organizations.

An example is a rice-fish symbiotic system Qingtian County, Zhejiang, China, with a 1,200-year-old history of production in practice (Min & Zhang, 2020). Before the GIAHS designation in 2005, the sale price was around RMB25 (approximately US$3.13[1]) per kg of fish in 2005. In 2015, the sale price increased to RMB70-80 (approximately US$10.77 to 12.31 in 2015[2]) per kg of fish. The rice was also traded for around RMB2,500 (approximately US$312.5 in 2005) per ton of husked rice before GIAHS designation; the price increased to RMB5,000 (approximately US$769.2 in 2015) per ton of husked rice value. The rice is packed as a gift and sold at a higher value-added price.

Another example is the terraced landscape of Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province (Gu et al., 2012). The terraced rice field landscape itself is less exclusionary as it is generally easily visible to everyone. However, Hani terraced rice fields can be given exclusivity with an observatory in the middle of a cliff with a good view when the terraced rice fields are not easily visible by planting standing trees on the road. The terraced rice fields cannot be seen from the road easily, but only on terraces. By secluding the viewpoint from the observatory, it is possible to impose the entrance fee, and it enables putting a market value to the rice paddy terrace landscape. Further, part of the admission fee income has been redistributed to the farmers for their landscape maintenance activities.

As methods to support and strengthen these management efforts to maintain the quality of the agricultural system, there are "geographical indications," "organic certification," and "other certification or labeling such as fair-trade.” Also, efforts have been made to promote agricultural products in these areas through "public relations" and "branding." This category involves discussions of how to expand the promotion of agricultural and cultural systems that utilize such a market-good approach.

Tea produced by Shizuoka's GIAHS tea grassland farming method is certified in three categories of farmers who practice tea grassland farming according to the ratio of the area of tea grassland they manage to the area of their tea gardens, and tea-related products they sell are labelled with the certification seal (Hidehiro & Yoshinobu, 2014). The high price-forming effect of GIAHS labelling on agricultural products and processed agricultural products with the seal of certification was shown to appear higher for gift-giving than for private use (Kurokawa et al., 2019). Thus, in the case of rare market goods, GIAHS registration is expected to be effective in price formation by storing the value of local agricultural products and processed agricultural products, and by promoting their value and contribution to agricultural culture, particularly for gift products.

Low excludability and high scarcity

Applying excludability to rural biodiversity and landscape is rather challenging as they are considered public goods. Therefore, a non-market approach to the conservation of GIAHS systems should be promoted. In the institutional approach, direct payments are made to the efforts of advanced biodiversity conservation for higher levels of conservation initiatives. One example is the agri-environment payment scheme in the UK, Japan, South Korea, and others (Legg, 2009). Although it is not an example of a GIAHS site, it is a national policy to conserve farmland biodiversities and other multiple functions or ecological services that it provides.

Ecological services, or ecosystem services, means the benefits humans receive from nature and its ecosystems (Daily, 1997). Also, other national governments aggregated regulatory authority for conservation and economic activity for a national park, and the national park committees provide governance, planning, policy, and programs that efficiently conserve the landscape and ecosystems. The introduction of these management initiatives requires financial support, which is inevitably limited to a certain extent depending on the country or area concerned. Still, the selection of initiatives is "subsidies to the landscape component," "volunteers and NPO activities support," and "conservation and economic activity aggregated to regulatory authority." These policy options in this category are worth considering.

As a citizen participatory approach, it includes landscape conservation by the NGOs and volunteers. In addition, it applies the use of citizen volunteers in scenic area conservation and its conservation activities. The volunteers also conserve both biodiversity and landscape in combination with a market approach, where they charge admission to the scenic area. In case of Aso grassland, the grasslands of Aso exist as the result of enormous volcanic activity that occurred long ago coupled with careful conservation and maintenance by the locals. NGO called “the Aso Green Stock” organizes and trains volunteers for grassland burning activities, which are essential for maintaining the grassland ecosystem. They do it by “Noyaki,” the controlled burning, in early spring. This large-scale activity has been ongoing for over 20 years, with approximately 2,000 volunteers participating annually. These volunteers undergo training to understand the risks and techniques involved in grassland burning, ensuring safe and effective management of the grasslands (Takahashi et al., 2017).

High excludability and low scarcity

Because excludability exists, it is possible to promote a market approach. However, despite the high price value of agricultural products in high excludability and high scarcity conditions, scarcity in this category is not high. In this case, an appropriate approach is to select financial resources acquisition toward conservation by the mass sale at a low value-added rate of each agricultural product. In other words, each product’s added value might be slim, however, the mass sale of the product can still acquire the finance necessary for conservation activities, and therefore a broad and shallow support is sought (Nomura & Yabe, 2014). Examples include products with a small environmental donation. Examples include Aeon's prepaid electronic money card of Aso, Kumamoto and the Senmaida owner system of Sado, Niigata.

The first example in this category is the prepaid electronic money card of AEON retail company, a specialist shopping mall developer in Japan. The AEON prepaid electronic money card is a pre-paid, rechargeable card. When you first purchase an AEON card, you can select the area where one wants to donate. Each time you purchase using the card, part of the utilization amount is donated to the fund-raising entity of the area selected. Thus, as a participatory approach, the fund-raising body can approach new customers to select the conservation area card. As the number of consumers with the card increases, the amount of donations that go to the area increases. More than a hundred cards from locals are registered and are supporting local activities, including one of the GIAHS sites for "Aso grassland regeneration fund-raising."

Another example is the Sado Ogura thousand rice terrace Ownership System. It asks consumers to be patrons of a rice-terraced paddy and support the local effort to maintain the rice terrace. In Japan, the rice terrace owner system has grown its popularity. It involves urban dwellers who provide financial and labor support to become owners of rice terraces and at the same time gain experience of being part of production and enjoy the rural environment. The city dwellers and farmers also can communicate with each other to understand the importance of conserving rural landscapes. The financial support is then used for the maintenance and restoration of the landscapes (Saito & Ichikawa, 2014). The selection of other measures in this High excludability and low scarcity category includes "certification system," "public relations," "quality improvement, and quantitative expansion of the production base." The challenge is expanding this approach further with a broad base.

Low excludability and low scarcity

From an ecological point of view or prevention of landslides, for example, sometimes maintenance activities for the agricultural system in the large scale of land area participation become important from the perspective of strengthening the foundation of the system. Important, however, that it is hard to limit the area and it is difficult to limit productivity, and therefore, scarcity of the product produced decreases. One example of the institutional approach is the maintenance support of general biodiversity through direct payment, such as in less favored areas. Such direct payment typically refers to financial assistance provided by governments or organizations to support agricultural activities in regions that face challenges such as poor soil quality, limited access to water, or harsh climatic conditions like hilly areas. These payments are often aimed at ensuring food security, promoting sustainable agriculture, and supporting rural development in areas where farming may be economically unviable without additional support. The choice of initiatives and support ranged from “direct payment system,” “support that strengthens volunteer activities,” and “human resource development” for learning support of traditional techniques. How to expand such initiative efforts can be a critical issue in maintaining the agricultural system's integrity.

One of the interesting cross GIAHS collaborations for human resource development is Ifugao Satoyama Meister Training Program (Buot, 2021). The Ifugao Satoyama Meister Training Program is a human capacity building initiative aimed at the sustainable development and conservation of the Ifugao Rice Terraces. This program was implemented in 2014 by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) through Kanazawa University, in collaboration with the Ifugao State University, University of the Philippines Open University, and the Provincial Government of Ifugao. It is an internaitonal collaboration program that focuses on empowering local stakeholders by providing them with the necessary knowledge and skills for sustainable development through research, seminars, skills training, and field exposures. The program supports numerous research projects, including assessments of the cultural and ecological significance of the Ifugao Rice Terraces. The program has developed through multiple phases, with Phase 2 starting in 2017, which included a twinning initiative with Japan’s Noto’s Satoyama and Satoumi. Currently, Phase 3 has been launched in 2021 to continue ongoing research and capacity building efforts.

SYSTEMS AND CONDITIONS FOR IMPLEMENTING SUPPORT MEASURES

This paper organizes approaches for agro-cultural conservation based on exclusiveness and scarcity. However, first, a means of assessing 'exclusiveness' and 'scarcity' and a system for implementing the considered approaches are needed. From this perspective, the selection of indicators for the assessment of agri-cultural diversity and the cooperation system between the relevant institutions are addressed.

Indicator for assessing the level and quality of agri-‘cultural’ diversity

Indicators are selected to facilitate a simple assessment of the level and quality of agri-‘cultural’ diversity within the agro-cultural system. By following changes in these indicators, the status of diversity and the effectiveness of specific conservation or management activities can then be conveniently assessed. Conservation activities are implemented as a menu of initiatives within the management, institutional, and public participation approaches financed by the market approach.

Institutionalization

A system is necessary for the market, institutional, and citizen participatory approaches to be implemented in an integrated and effective manner. For example, National Parks in Japan incorporate a wide range of relevant agencies, including local authorities, public bodies, and private organizations. These bodies are not merely named there but have their own areas of responsibility and tasks. The government should actively seek partnerships with NPOs, citizens' groups involved in conservation, and even private companies. It is also necessary to bring in volunteers from outside rather than managing within the registered area with a limited number of civil servants and other staff. If the relevant organizations lack the know-how to attract volunteers, they could reinforce this weakness by adding organizations that specialize in such activities as partners.

CONCLUSION

As described above, it is important for Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems and candidate sites, or potential candidate sites, to take into account the characteristics of the area and the characteristics of the goods and services that can be sold in order to conserve and manage the agro-cultural system and promote the area, as well as support measures. Therefore, this study proposed options for agro-cultural system conservation measures and regional development methods according to each region's natural and cultural characteristics, the actors' conditions, and the potential for administrative support.

REFERENCES

Buot, I. E. (2021). Its Organic Agriculture Practices, Current Challenges, and Initiatives. Journal of Nature Studies, 20(2), 22–32.

Daily, G. C. (1997). Introduction: what are ecosystem services. Nature’s services: Societal dependence on natural ecosystems, 1(1).

FAO. (2006). Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) -A Heritage for the Future-. www.fao.org/icatalog/inter-e.htm

Gu, H., Jiao, Y., & Liang, L. (2012). Strengthening the socio-ecological resilience of forest-dependent communities: The case of the Hani Rice Terraces in Yunnan, China. Forest Policy and Economics, 22, 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2012.04.004

Hidehiro, I., & Yoshinobu, K. (2014). Assessment of GIAHS in Shizuoka: The Traditional Tea-Grass Integrated System. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 5(4), 398–401. https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2014.04.017

Hisako, N., & Mitsuyasu, Y. (2014). Private Provision of Environmental Public Goods: A Pilot Program for Agricultural Heritage Conservation. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 5(4), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2014.04.009

Kurokawa, T., Yabe, M., Nomura, H., & Takahashi, Y. (2019). Consumer Valuation of Green Tea Leaves Produced through Chagusaba Farming: A Case of GIAHS in Shizuoka. Journal of Rural Problems, 55(2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.7310/arfe.55.81

Legg, W. (2009). Payments for agri-environmental services: an OECD perspective. In New Perspectives on Agri-environmental Policies (pp. 55-65). Routledge.

Min, Q., & Zhang, B. (2020). Research progress in the conservation and development of china-nationally important agricultural heritage systems (China-NIAHS). Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010126

Saito, O., & Ichikawa, K. (2014). Socio-ecological Systems in Paddy Dominated Landscapes in Asian Monsoon. In Nishikawa Usio & Miyashita Tadashi (Eds.), Social-ecological Restoration in Paddy-Dominated Landscapes: Springer, Tokyo (pp. 1–311).

Takahashi, Y., Neef, A., & Yokogawa, H. (2017). Conservation and Restoration of traditional grasslands in the Mount Aso Region of Kyushu, Japan -The Role of collaborative management and public policy support. In M. Cairns (Ed.), Shifting cultivation policies: Balancing environmental and social sustainability. CABI. (pp. 1–1057). CABI. https://cabidigitallibrary.org

[1] 8 RMB = about 1 US dollar in 2005

[2] 6.5 RMB = about 1 US dollar in 2015