ABSTRACT

Organic farming of coffee among Taiwan’s Indigenous communities has rapidly emerged as a vital farming occupation with the potential to provide much-needed socioeconomic support for this community. In Taiwan, Indigenous communities are often in marginalized positions. They make up less than 3% of the population and are mostly concentrated in rural regions, which are most likely to bear the brunt of the annual typhoons that the country suffers from. Organic coffee has emerged as a popular occupation among Indigenous farming communities. It has the potential to contribute significantly to improving the socio-economic welfare of these Indigenous communities. In this article, we discuss the socioeconomic issues facing Taiwan’s Indigenous communities and provide a background on their roles in Taiwan’s agriculture. In particular, we discuss the history and process of Indigenous communities adopting highland coffee production and the potential of this to tie in with government policy regarding conservation and its rural revitalization policies.

Keywords: Organic farming, Indigenous farming, Rural revitalization, Taiwan agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Organic farming and eco-tourism have the potential to solve or alleviate several of the socioeconomic challenges facing Indigenous Taiwan people—a community that can be described as economically marginalized. The unique nature of Indigenous culture and Indigenous territory makes them ripe or well-suited for organic farming and ecotourism. In addition, Taiwan’s government development and farming policy for organic farming, rural tourism, and rural revitalization also mean that Indigenous communities stand to benefit from adopting organic farming and eco-tourism.

Taiwan's Indigenous people are a marginalized group who make up less than 3% of the population of Taiwan. While the majority of Taiwan’s population are Han Chinese, Taiwan’s Indigenous people constitute 16 officially recognized Indigenous tribes. These tribes include Amis, Tsou, Paiwan, and so on. Most are located in three major regions of Taiwan—around the Central Mountain Range, in the East Rift Valley, or the east coastal area. These regions are mostly inland and mountainous, and these communities are faced with several socioeconomic challenges, such as aging populations, lack of social amenities, and high levels of poverty. They are susceptible to bearing the brunt of typhoons. Also, the mountainous areas of these regions make them difficult to farm, prone to erosion and landslides, and at high risk of typhoons and earthquakes (Bayrak, 2022). Moreover, because of the rural nature of the homelands of these Indigenous tribes, they also suffer heavily from the aging population phenomenon in Taiwan. This means there are not enough young people to work on farms and whatever other industries may still be intact in these areas, as young people migrate to the larger cities for better job opportunities.

A brief sociocultural history of farming among Taiwan’s Indigenous people

Taiwan’s Indigenous farming before Han migration revolved around plant cultivation (e.g., taro, millet cultivation), and the hunting of wild deer (Yen & Chen, 2016). Slash and burn agriculture (or Swidden cultivation) was a major part of Indigenous agriculture (Yen & Chen, 2016). This included clearing away woodlands by cutting down trees and vegetation and then burning it. Then, this newly cleared ground would be planted and harvested and after a few years of use would be allowed to rest or fallow, while the community moved to a new spot to repeat the same process all over again. Contact with Han Chinese communities quickly led to the adoption of rice farming (Kang, 2003). Today, most Indigenous communities are based in rural mountainous areas, with some located in coastal areas, and several communities with livelihoods that revolve around fishing and other marine-based economic activities. However, modern life and industry have been embraced by Taiwan’s Indigenous people, with many of them migrating to major urban areas to pursue livelihoods other than farming.

There are several challenges facing Indigenous peoples in terms of farming. Their farms are usually located in mountainous regions, which exposes them to high risks of soil erosion and landslides. In particular, the eastern and central regions in which the majority of Indigenous communities reside are the parts of Taiwan most frequently hit by typhoons during Taiwan’s typhoon season. Typhoons in the past have caused much damage to property and farms, including increasing the risks of erosions and landslides, in Indigenous areas, with the most notable example being Typhoon Morakot (Bayrak et al., 2023).

Characteristics of Indigenous farming in Taiwan today

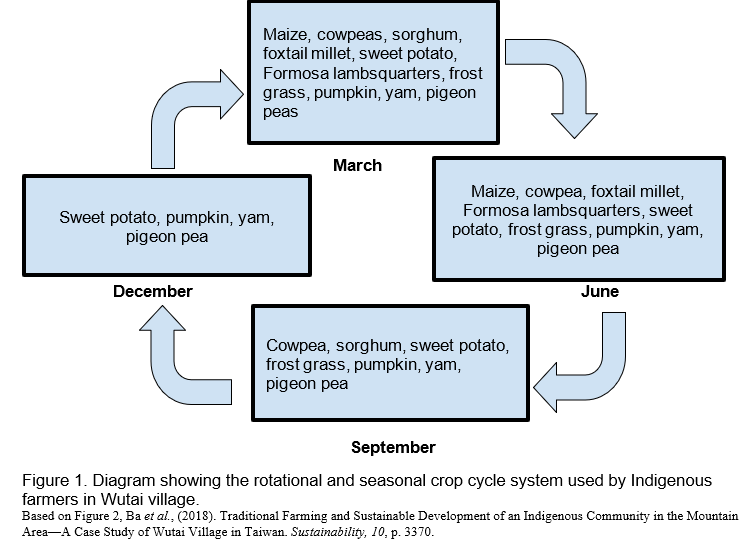

Farming among Taiwan’s Indigenous farmers was severely affected by Typhoon Morakot (Bayrak et al., 2023). This led to massive displacement of Indigenous farmers, often to urban areas for industrial or factory jobs. Since then, researchers have observed several case studies of Indigenous communities recovering or maintaining, to some extent, their past agrarian livelihoods into the present. Taiwan’s Indigenous farming today is typically characterized by intercropping, with several crops being grown at the same time according to the season or time of year. A fallow system is often practiced with cultivated plots taking a break from intensive cultivation while the community moves on to farm new plots. Figure 1 is a depiction of the rotational and intercropping system adopted among the Rukai Indigenous people in Wutai Village (Ba et al., 2018).

For example, Yen and Chen (2016) carried out a study on how the Tayal Indigenous community in Hsinchu practiced agroforestry. In this community, they retained the slash-and-burn method of agriculture. This includes finding appropriate hilly areas and trees that can be used as fertilizer as they do not use chemical fertilizers. They grow a variety of crops, including beans, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, millet, and taro, which are rotated based on the planting season for each of these crops. Yen and Chen (2016) described Tayal farming methods as a form of a responsible or sustainable agroforestry system. For example, they described how white poplars were used for natural fertilizers in between the fallow or resting periods for the cultivated plots. These cultivated plots are maintained for 10 years, and within that period, the white poplars rapidly grow to create lush forests. These poplars are selected especially for their specific ability to grow rapidly. So, whereas slash-and-burn agriculture is often seen as harmful to the environment, as carried out by the Tayal farming community it has the potential to represent sustainable agroforestry practice.

Huang et al., (2021) examined community resilience among Indigenous farming communities in Pingtung and observed how their adoption of Indigenous quinoa (Chenopodium formosanum) was simultaneously and paradoxically associated with both the re-agrarianization and de-peasantization of Taiwan’s Indigenous farmers. Young Indigenous farmers in choosing to cultivate a crop meant to meet a new market demand for a superfood were choosing to leave modern urban or industrial jobs in favor of agriculture while turning away from traditional farming practices. Also, the process led to significant enhancement in community resilience according to the authors. Chang (2019) also described how coffee cultivation among the Amis people in Kalala was taken on as an answer to the marginal socioeconomic conditions facing that community. Kalala, which is a tiny village located in East Taiwan, has always been at the center of coffee cultivation in Taiwan, especially during the period of Japanese colonization. With the increased local demand for specialty coffee in Taiwan, Kalala Amis farmers practice organic farming of coffee, which includes permaculture, a process of relying on cultivation systems that mimic natural or local ecosystems and a composting method invented by a Japanese agricultural expert—bokashi—which uses manuring strategies that promote the production of beneficial bacteria to increase fertility in a circular ecosystem.

Ba et al. (2016) studied Indigenous farming among the Rukai of Wutai village in Taiwan. They observed how several traditional farming practices were continued, such as rotational cropping, intercropping, and fallowing. In addition, this community continues to ensure that its agricultural practices are closely linked to traditional Rukai cultural activities and celebrations. For example, July, which represents the end of the year in the Rukai calendar, is also the end of the harvest season. August, the beginning of the Rukai calendar year, is dedicated to harvest celebrations, including major traditional ceremonies. The authors noted the success and potential of these farming methods in preserving traditional crop diversity and attracting eco- and agritourism, respectively.

THE POTENTIAL FOR ORGANIC FARMING AND AGRITOURISM AMONG INDIGENOUS FARMERS

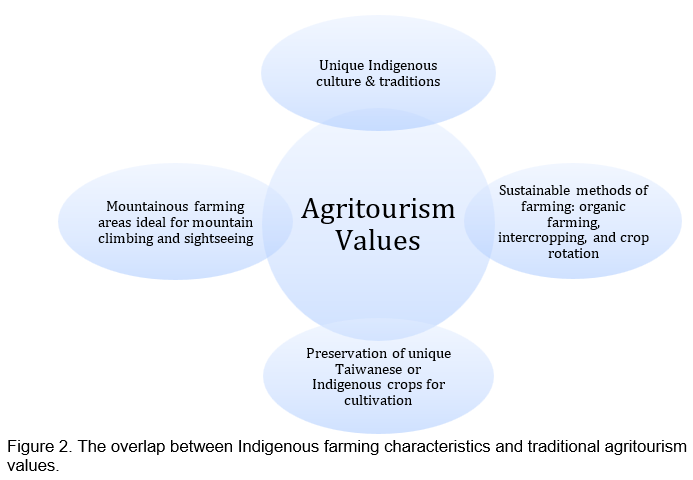

Although the mountainous nature and distant location of Indigenous farming territory may at first glance appear to be a disadvantage, several factors make these areas ideal for organic farming, agritourism, and ecotourism: 1) Indigenous farmers have a unique culture that can be attractive to both foreign and local tourists; 2) The mountainous areas are ideal for organic farming, which helps reduce soil erosion on steep slopes that characterize mountainous regions (Ba et al., 2018; Yen et al., 2016); and 3) Indigenous traditional farming methods, which make limited use of fertilizers and crop rotation (Ba et al., 2018; Yen et al., 2016), are in line with sustainable methods of cultivation that can support agritourism. Figure 2 illustrates how the traditional characteristics of Indigenous farming can fit well with agritourism values.

COFFEE: AN IDEAL CASH CROP FOR TAIWAN’s INDIGENOUS SMALL FARMERS?

In Taiwan, the coffee industry gained the attention of policymakers after the catastrophic 1999 earthquake (Wang et al., 2019). In counties like Yunlin and Nantou, betel nut and tea cultivation were replaced by coffee (Nicole, 2022). One of the underlying factors behind policymakers promoting coffee cultivation over betel nut, besides discouraging the consumption of the cancer-causing betel nut, was the fact that it protected the soil better. Coffee roots went deeper and were more protective of soils in hilly and mountainous regions; therefore, they were better at protecting against landslides and erosion than betel nut, which has a quite shallow root system (Taiwan Scene, 2022). This fact was emphasized by the massive soil erosion and landslides that resulted from frequent typhoons.

Taiwan’s Indigenous farmers have embraced the cultivation of coffee. As the demand for specialty coffee in Taiwan expanded, Indigenous farmers in Taiwan have adapted to new methods of cultivating coffee, which have often been led by younger generations who have migrated from urban areas back to their rural homelands (Wang et al., 2019). The new coffee industry is also characterized by an emphasis on appealing to the specialty coffee market. As a result, coffee contests have been set up by the state and other NGOs, which are meant to improve the quality of their coffee and to learn innovative ways of marketing coffee to consumers. Indigenous-owned coffee estates such as the Tsou estate in Ali-Shan have grown famous for the numerous awards that they have won for their specialty coffee (Antoine, 2023).

Indigenous farmers have increasingly adopted coffee in Taiwan as a non-traditional crop. The crop has great potential as an agritourism crop, especially if these farms adopt specialty coffee. Specialty coffee as opposed to commercial coffee refers to coffee grown sustainably. This would mean coffee grown on family farms, as opposed to large estates; coffee grown on farms that employ well-paid labor, instead of cheap underpaid labor; and coffee that protects the environment, for example, through limited use of pesticides and fertilizers or organic farming (Pico-Mendoza, 2020). Examples of specialty coffee culture include Costa Rica (Pico-Mendoza, 2020), Rwanda (van Kollenburg & van Weert, 2024), and Taiwan itself (Chang, 2019). Another aspect of specialty coffee refers to its taste. Commercial coffee is often considered to have a bitter taste because it is roasted dark to cover up any inconsistency due to mixed beans and being of inferior quality.

By contrast, in specialty coffee, there is an emphasis on the fruity or floral flavors of coffee, which are far different from the bitter taste profiles that are often associated with commercial coffee. A whole gourmet industry and culture similar to tea or wine has arisen around specialty coffee as a result of this. The specialty coffee industry has a grading system that qualifies different types of coffee according to their taste. The best quality often fetches a high price. For example, in Taiwan, the most expensive coffee went for a remarkable price of US$1,103.4 per kilogram in 2022 (Lin, 2022). Growing specialty coffee requires special training in recognizing its flavors and careful harvesting to ensure that only properly ripened beans are picked.

Although the volumes of specialty coffee can be much smaller than commercial coffee, for small farmers, specialty coffee can be an ideal crop to improve the incomes of small farmers. The volumes of specialty coffee are typically smaller because the crop is labor-intensive. It requires coffee berries to be picked by hand to ensure quality. Also, specialty coffee is often organic, which means limited or no use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. In other words, weeds and pests would have to be removed through intensive manual labor.

The agritourism potential of coffee in Taiwan

The potential for specialty coffee in Taiwan rests on the high demand for coffee in the country and the growing interest among Taiwan consumers in learning about specialty coffee or participating in gourmet coffee culture. The high price of specialty coffee is comparable to the premium prices associated with organic products. Indeed, much of the specialty coffee is already organic. In addition, the coffee farms can serve as agritourism sites, where tourists get the chance to learn about the process of making specialty coffee from bean to brewed cup. The coffee industry in Taiwan has been boosted by the massive demand for coffee among Taiwan’s consumers. For the first time in 2020, Taiwan consumers began consuming more coffee than tea, in a country where tea has been the national beverage for hundreds of years; according to the latest data available, Taiwan customers consumed approximately 2.85 billion cups of coffee a year (USDA, 2021).

The characteristics of specialty coffee also make it suitable for agritourism and ecotourism. Ethical-minded customers would want to see or verify the “sustainable” nature of the specialty coffee that they consume. Agritourism often involves visitors participating in farm activities and learning about the process that goes into the products that they consume. Specialty coffee focuses on tracing every batch or even cup of coffee back to the farm or lot on which it was grown. This trait fits in well with the sustainable motivations of agritourism. On a specialty coffee farm, visitors are allowed the opportunity to witness, verify, and experience firsthand the process of growing and making coffee in a manner that fits their sustainable values.

In addition, the culture around tasting specialty coffee means that visitors could also participate in coffee-tasting educational activities. The unique and complicated tasting profile of coffee invites curiosity and opportunities for education that are comparable to experiential tourism in the wine industry (Govindasamy & Kelley, 2014; Vaquero Piñeiro et al., 2022). Indeed, there is now a growing body of research indicating the potential of specialty coffee in experiential agritourism showing the potential of coffee in developing rural areas (Bowen, 2021). In the case of Taiwan’s Indigenous communities, their unique culture could contribute toward creating a unique agritourism experience centered around coffee farms.

The case study of Kalala: a rejuvenated coffee basket

Kalala, which is a small Indigenous Amis village located in East Taiwan provides an excellent example of the potential of coffee to meet the socioeconomic challenges faced by Indigenous communities in Taiwan as reported by Chang (2019). According to the author, this small rural community has a long history of coffee production; it was a major “coffee basket” during the Japanese colonial period. However, most of the coffee produced by Kalala was exported directly to Japan. The producers were not in any way involved with roasting the coffee, and most of them until recently had not even had a cup of coffee to taste themselves. This gap in knowledge and value between the farmer and his final product is comparable to cocoa production in West Africa, where farmers in countries like the Ivory Coast and Ghana are stuck at the lower end of the value chain and benefit in no way from the production of the high-value chocolate end product (Beg, 2017). After the collapse of Japanese colonial ruling, commercial coffee production in the area all but disappeared. In addition, the community can be described as aging, which means that the majority of its inhabitants are older residents. Many of the younger residents in that community had migrated to industrial hubs located in Changhua, Xizhi, and Taoyuan, seeking jobs in factories and the large industrial estates located there (Chang, 2019).

The community participated in the Rural Rejuvenation Program in 2005. However, they had been disappointed with the results, with many of them complaining that farmers who belonged to the Han majority were the only ones who benefited. After consulting with and taking advice from a team of experts from Dong Hwa University, they broke away from the wider farming group or cooperative associated with the Rejuvenation Program and created their cooperative organization. This organization relied on conventional cooperative methods and traditional Amis farming practices to sustain itself. In their attempts to rejuvenate their community, the Amis farmers revived the production of organic coffee, in which they were faced with several challenges.

As mentioned earlier, many of these farmers had never tasted a cup of coffee themselves; they simply stuck to production. However, the nature of specialty coffee necessitates that the farmer has knowledge of coffee quality as judged by taste. Other problems they faced included: 1) having limited funds to purchase or qualify for organic certification; 2) not having a large enough scale to support larger marketing efforts; 3) the advanced age of many farmers; and 4) rural emigration, with large numbers of working age young people living for better economic opportunities in bigger towns and cities.

These farmers have used a combination of modern methods and traditional Indigenous culture to achieve success in growing organic coffee. For example, they have pushed for organic certification and organized themselves into a farmers’ cooperative. In addition, they also practiced intercropping—a farming method that has been associated with traditional Indigenous farming and which guarantees a constant source of income throughout the year based on the crop that is in season. There has also been an emphasis on marketing and selling directly to consumers instead of relying on middlemen. The agritourism efforts in Kalala appear to be at the beginning stages. The cooperative has arranged for visitors to come to their farm, an initiative that is encouraged by their management of social media sites on Facebook. The visits were designed to “understand how the farm worked . . . to recover the local ecosystem by farming in a more natural way” (Chang, 2019, p. 197).

In short, the case study of Kalala highlights both the challenges and benefits that Indigenous farmers face in both organic farming and organic tourism. It shows that traditional Indigenous farming practices can match the values of organic farming and agritourism. For example, Indigenous farming practices that seek to preserve local plants with little perceived commercial value can be described as preserving biodiversity. In addition, to deal with the farming labor shortage in Kalala, they make use of malaplaiw—a traditional farming practice where labor is shared among farmers. That is, farmers take turns working on each other’s farms during periods of intensive labor, such as the harvesting season.

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Agritourism in Taiwan is a vibrant industry and is supported by the country’s large and dense urban populations, who often use agritourism farms as a break from the busyness of Taiwan’s large cities and an opportunity to interact with farm animals and engage in agricultural activity, such as fruit picking (Liang et al., 2021). The Council of Agriculture (COA, 2021), as of 2020 granted licenses to 486 leisure farms in Taiwan. Taiwan leisure farms are diverse. They include facilities and activities, such as fish farms, fruit orchard farms, animal ranches, bee farms, tea farms, and farm museums. Some of them are quite large, such as the Long Yun Farm, which measures up to 400 ha, whereas others are smaller and are typical of Taiwan’s family farms at less than 2 ha, such as the Forest 18 Leisure Farm. According to Taiwan’s Council of Agriculture (Hsieh & Antoine, 2023; COA, 2021), as of 2019, Taiwan saw 27.8 million tourist journeys to rural and leisure travel destinations; of that number, 77,000 were foreign tourists. In addition, the production value of these travels amounted to NT$10.9 billion (or just over US$341 million). These policies relate to objectives such as 1) regularizing and upgrading the leisure farm industry, 2) developing experiential niche agricultural activities, 3) marketing agritourism to tourists abroad, 4) increasing tourist numbers to local areas, and 5) providing subsidies to support agribusiness enterprises (Hsieh & Antoine, 2021).

Agritourism among Indigenous farmers in Taiwan has tremendous potential; however, this potential has yet to be fully exploited. Several factors support the agritourism potential for Indigenous communities: 1) Indigenous farming practices are often sustainable and eco-friendly; 2) Indigenous farming is community-based farming, which supports the needs of these communities; 3) Indigenous farming practices provide the ideal opportunity for educational activities that are typical of agritourism. Indigenous traditional farming often relies on permaculture, that is, an approach to farming that seeks to emulate natural ecosystems (Chang, 2019). This can be seen in the kind of agroforestry system practiced by the Tayal Indigenous community in Hsinchu (Yen & Chen, 2016). In addition, Indigenous communities practice other eco-friendly farming strategies such as intercropping, rotation, organic farming, and fallowing (i.e., allowing the land to rest for a certain period after harvest). All these practices are in line with the sustainability ethic that is often associated with agritourism.

Specialty coffee is an ideal crop for organic farming and agritourism. It has recently attracted attention because of its association with sustainability and the issue of traceability. Most commercial coffee exploits cheap labor and supports massive corporations, whereas specialty coffee is often seen as promoting local farmers and supporting local communities, who get paid higher wages because of the premium prices associated with specialty coffee. Also, specialty coffee belongs to a gourmet culture that can attract much curiosity and opportunities for learning in the context of agritourism. Lastly, because of the emphasis on sustainability, specialty coffee often relies on organic farming. Coffee was historically grown in Indigenous areas, and this provides unique opportunities for these Indigenous folks.

One of the core principles of agritourism and organic farming is community support (Sulistyowati, 2023). Because Indigenous communities are often rural people who suffer from problems like an aging population and high levels of unemployment, agritourism would be ideal. Agritourism has the potential to support farmers directly by allowing them to sell their produce directly. The increased economic opportunities may improve employment and even induce farmers to return from larger industrial centers to their hometowns. This was the case in Kalala, where aging farmers left the big cities when they were no longer of working age to return home to Kalala to take up organic coffee farming (Chang, 2019). Regarding educational activities, the process of growing organic crops provides an opportunity for visitors to learn and participate in sustainable farming practices.

Although there is much potential for organic farming within the context of agritourism among Indigenous communities, policy support from the government is required to fulfill said potential. For example, the cost of certification can be prohibitive, which means that farmers often struggle to obtain the certification necessary to sell their produce at premium prices. This is somewhat ironic considering that poor farmers typically farm without chemical pesticides and fertilizers because they are unable to afford them (Parrott et al., 2006). Subsidies to reduce the cost of certification for farmers would be helpful in that regard. Moreover, although Indigenous communities may have ideal characteristics, such as mountainous scenery and other picturesque rural landscapes, they require help with marketing to make these locations known to the public. Policymakers could think of providing farmers with the proper training in marketing.

Another major issue facing rural Indigenous communities and Taiwan in general is the labor shortage in the agricultural sector due to the aging population phenomenon (Chen, 2023). The remaining farmers in Taiwan are both too old and too few. This shortage of farmers poses a serious challenge to creating a viable agricultural industry in small rural Indigenous communities. Taiwan for other sectors of its economy, such as manufacturing, relies on foreign labor. Such a solution could be considered for its farming sector. Another long-term solution would involve coming up with policies to make organic farming and agritourism more attractive to young Indigenous people residing in the countryside. Making credit available to undertake modern farm enterprises would be one way of attracting these young folks back to their communities.

REFERENCES

Antoine, M. (2023, October). Coffee so green. https://bluedotliving.com/coffee-so-green/

Ba, Q.-X., Lu, D.-J., Kuo, W.H.-J., & Lai, P.-H. (2018). Traditional Farming and Sustainable Development of an Indigenous Community in the Mountain Area—A Case Study of Wutai Village in Taiwan. Sustainability, 10, 3370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103370

Bayrak, M.M. (2022). Does Indigenous tourism contribute to Indigenous resilience to disasters? A case study on Taiwan's highlands. Progress in Disaster Science, 14, 100220.

Bayrak, M. M., Hung, L. S., & Hsu, Y. Y. (2023). Living with typhoons and changing weather patterns: Indigenous resilience and the adaptation pathways of smallholder farmers in Taiwan. Sustainability Science, 18(2), 951–965.

Beg, M.S., Ahmad, S., Jan, K., & Bashir, K. (2017). Status, supply chain and processing of cocoa-A review. Trends in food science & technology, 66, 108–116.

Bowen, R. (2021). Cultivating coffee experiences in the Eje Cafetero, Colombia. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(3), pp. 328-339. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-08-2020-0184

Chang, C.W. (2019). An Alternative Agricultural Space in an Indigenous Community: Kalala, Taiwan. In: Leimgruber, W., Chang, Cy. (eds.), Rural Areas Between Regional Needs and Global Challenges. Perspectives on Geographical Marginality, vol 4. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04393-3_11

Chen, C.H. (2023). Taiwan’s Rapidly Aging Population: A Crisis in the Making? Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

Council of Agriculture [COA]. (n.d.) Overview. COA. https://eng.moa.gov.tw.

Diamond, J. (2000). Taiwan's gift to the world. Nature, 403, 709–710. https://doi.org/10.1038/35001685

Govindasamy, R. and Kelley, K. (2014). Agritourism consumers’ participation in wine tasting events: An econometric analysis. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 26(2), pp. 120-138. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-04-2013-0011

Hsieh, C. M., & Antoine, M. The Role of Agritourism in Taiwan's Rural Revitalization Strategy The Role of Agritourism in Taiwan's Rural Revitalization Strategy. FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform.

Huang, S. M., Che-Hao, H., & Chang, Y. H. (2021). The paradox of cultivating community resiliency: Re-agrarianisation and De-peasantisation of indigenous farmers in Taiwan. Journal of Rural Studies, 83, 96–105.

Kang, P. (2003). A Brief Note on the Possible Factors Contributing to the Large Village Size of the Siraya in the Early Seventeenth Century. In Leonard Blusse (ed.), Around and About Formosa. Taipei, SMC Publishing. pp. 111–127.

Liang, A. R. D., Hsiao, T. Y., Chen, D. J., & Lin, J. H. (2021). Agritourism: Experience design, activities, and revisit intention. Tourism Review, 76(5), 1181-1196.

Linton, A. (2008). A niche for sustainability? Fair labor and environmentally sound practices in the specialty coffee industry. Globalizations, 5(2), 231–245.

Liu, Shang-Yu, Chen-Ying Yen, Kuang-Nan Tsai, & Wei-Shuo Lo. (2017). A Conceptual Framework for Agri-Food Tourism as an Eco-Innovation Strategy in Small Farms. Sustainability 9(10), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101683

Nicole, L. (2022, September 19). Wake up to high-scoring coffees from Taiwan. Coffee Knowledge Hub. https://coffeeknowledgehub.com/it/news/wake-up-to-high-scoring-coffees-from-taiwan

Parrott, N., Olesen, J. E., & Høgh-Jensen, H. (2006). Certified and non-certified organic farming in the developing world. In Global development of organic agriculture: Challenges and prospects (pp. 153-179). Wallingford UK: CABI Publishing.

Pico-Mendoza, J., Pinoargote, M., Carrasco, B., & Limongi Andrade, R. (2020). Ecosystem services in certified and non-certified coffee agroforestry systems in Costa Rica. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44(7), 902-918.

Sulistyowati, C. A., Afiff, S. A., Baiquni, M., & Siscawati, M. (2023). Challenges and potential solutions in developing community supported agriculture: a literature review. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 47(6), 834-856.

Taiwan Scene. (January 18, 2022). How Taiwanese Coffee is Stimulating Sustainable Farming. Taiwan Scene.

https://taiwan-scene.com/how-taiwanese-coffee-is-stimulating-sustainable....

USDA (2021). Opportunities for US Coffee Percolate in Taiwan Brewing Market. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Opportunities%20for%20US%20Coffee%20Percolate%20in%20Taiwan%20Brewing%20Market_Taipei%20ATO_Taiwan_04-27-2021#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20recent%20survey,growth%20rate%20of%2020%20percent.

van Kollenburg, G., & van Weert, P. (2024). Coffee, climate, community: A holistic examination of specialty coffee supply chains in Rwanda (in press). Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3000

Wang, M. J., Chen, L. H., Su, P. A., & Morrison, A. M. (2019). The right brew? An analysis of the tourism experiences in rural Taiwan's coffee estates. Tourism management perspectives, 30, 147-158. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2211973619300200

Vaquero Piñeiro, M., Tedeschi, P., & Maffi, L. (2022). Italy Tasting: Wine, Tourism, and Landscape. In A History of Italian Wine: Culture, Economics, and Environment in the Nineteenth through Twenty-First Centuries (pp. 191-231). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Yen, A. C., & Yin-An, C. (2016). Agroforestry as sustainable agriculture: an observation of Tayal indigenous people’s collective action in Taiwan. The International Journal of Environmental Sustainability, 13(1), 1.

Yu, C.-Y. An Application of Sustainable Development in Indigenous People’s Revival: The History of an Indigenous Tribe’s Struggle in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093259

Agritourism Potential Among Taiwan’s Indigenous Communities, with Emphasis on Organic Coffee Farming

ABSTRACT

Organic farming of coffee among Taiwan’s Indigenous communities has rapidly emerged as a vital farming occupation with the potential to provide much-needed socioeconomic support for this community. In Taiwan, Indigenous communities are often in marginalized positions. They make up less than 3% of the population and are mostly concentrated in rural regions, which are most likely to bear the brunt of the annual typhoons that the country suffers from. Organic coffee has emerged as a popular occupation among Indigenous farming communities. It has the potential to contribute significantly to improving the socio-economic welfare of these Indigenous communities. In this article, we discuss the socioeconomic issues facing Taiwan’s Indigenous communities and provide a background on their roles in Taiwan’s agriculture. In particular, we discuss the history and process of Indigenous communities adopting highland coffee production and the potential of this to tie in with government policy regarding conservation and its rural revitalization policies.

Keywords: Organic farming, Indigenous farming, Rural revitalization, Taiwan agriculture

INTRODUCTION

Organic farming and eco-tourism have the potential to solve or alleviate several of the socioeconomic challenges facing Indigenous Taiwan people—a community that can be described as economically marginalized. The unique nature of Indigenous culture and Indigenous territory makes them ripe or well-suited for organic farming and ecotourism. In addition, Taiwan’s government development and farming policy for organic farming, rural tourism, and rural revitalization also mean that Indigenous communities stand to benefit from adopting organic farming and eco-tourism.

Taiwan's Indigenous people are a marginalized group who make up less than 3% of the population of Taiwan. While the majority of Taiwan’s population are Han Chinese, Taiwan’s Indigenous people constitute 16 officially recognized Indigenous tribes. These tribes include Amis, Tsou, Paiwan, and so on. Most are located in three major regions of Taiwan—around the Central Mountain Range, in the East Rift Valley, or the east coastal area. These regions are mostly inland and mountainous, and these communities are faced with several socioeconomic challenges, such as aging populations, lack of social amenities, and high levels of poverty. They are susceptible to bearing the brunt of typhoons. Also, the mountainous areas of these regions make them difficult to farm, prone to erosion and landslides, and at high risk of typhoons and earthquakes (Bayrak, 2022). Moreover, because of the rural nature of the homelands of these Indigenous tribes, they also suffer heavily from the aging population phenomenon in Taiwan. This means there are not enough young people to work on farms and whatever other industries may still be intact in these areas, as young people migrate to the larger cities for better job opportunities.

A brief sociocultural history of farming among Taiwan’s Indigenous people

Taiwan’s Indigenous farming before Han migration revolved around plant cultivation (e.g., taro, millet cultivation), and the hunting of wild deer (Yen & Chen, 2016). Slash and burn agriculture (or Swidden cultivation) was a major part of Indigenous agriculture (Yen & Chen, 2016). This included clearing away woodlands by cutting down trees and vegetation and then burning it. Then, this newly cleared ground would be planted and harvested and after a few years of use would be allowed to rest or fallow, while the community moved to a new spot to repeat the same process all over again. Contact with Han Chinese communities quickly led to the adoption of rice farming (Kang, 2003). Today, most Indigenous communities are based in rural mountainous areas, with some located in coastal areas, and several communities with livelihoods that revolve around fishing and other marine-based economic activities. However, modern life and industry have been embraced by Taiwan’s Indigenous people, with many of them migrating to major urban areas to pursue livelihoods other than farming.

There are several challenges facing Indigenous peoples in terms of farming. Their farms are usually located in mountainous regions, which exposes them to high risks of soil erosion and landslides. In particular, the eastern and central regions in which the majority of Indigenous communities reside are the parts of Taiwan most frequently hit by typhoons during Taiwan’s typhoon season. Typhoons in the past have caused much damage to property and farms, including increasing the risks of erosions and landslides, in Indigenous areas, with the most notable example being Typhoon Morakot (Bayrak et al., 2023).

Characteristics of Indigenous farming in Taiwan today

Farming among Taiwan’s Indigenous farmers was severely affected by Typhoon Morakot (Bayrak et al., 2023). This led to massive displacement of Indigenous farmers, often to urban areas for industrial or factory jobs. Since then, researchers have observed several case studies of Indigenous communities recovering or maintaining, to some extent, their past agrarian livelihoods into the present. Taiwan’s Indigenous farming today is typically characterized by intercropping, with several crops being grown at the same time according to the season or time of year. A fallow system is often practiced with cultivated plots taking a break from intensive cultivation while the community moves on to farm new plots. Figure 1 is a depiction of the rotational and intercropping system adopted among the Rukai Indigenous people in Wutai Village (Ba et al., 2018).

For example, Yen and Chen (2016) carried out a study on how the Tayal Indigenous community in Hsinchu practiced agroforestry. In this community, they retained the slash-and-burn method of agriculture. This includes finding appropriate hilly areas and trees that can be used as fertilizer as they do not use chemical fertilizers. They grow a variety of crops, including beans, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, millet, and taro, which are rotated based on the planting season for each of these crops. Yen and Chen (2016) described Tayal farming methods as a form of a responsible or sustainable agroforestry system. For example, they described how white poplars were used for natural fertilizers in between the fallow or resting periods for the cultivated plots. These cultivated plots are maintained for 10 years, and within that period, the white poplars rapidly grow to create lush forests. These poplars are selected especially for their specific ability to grow rapidly. So, whereas slash-and-burn agriculture is often seen as harmful to the environment, as carried out by the Tayal farming community it has the potential to represent sustainable agroforestry practice.

Huang et al., (2021) examined community resilience among Indigenous farming communities in Pingtung and observed how their adoption of Indigenous quinoa (Chenopodium formosanum) was simultaneously and paradoxically associated with both the re-agrarianization and de-peasantization of Taiwan’s Indigenous farmers. Young Indigenous farmers in choosing to cultivate a crop meant to meet a new market demand for a superfood were choosing to leave modern urban or industrial jobs in favor of agriculture while turning away from traditional farming practices. Also, the process led to significant enhancement in community resilience according to the authors. Chang (2019) also described how coffee cultivation among the Amis people in Kalala was taken on as an answer to the marginal socioeconomic conditions facing that community. Kalala, which is a tiny village located in East Taiwan, has always been at the center of coffee cultivation in Taiwan, especially during the period of Japanese colonization. With the increased local demand for specialty coffee in Taiwan, Kalala Amis farmers practice organic farming of coffee, which includes permaculture, a process of relying on cultivation systems that mimic natural or local ecosystems and a composting method invented by a Japanese agricultural expert—bokashi—which uses manuring strategies that promote the production of beneficial bacteria to increase fertility in a circular ecosystem.

Ba et al. (2016) studied Indigenous farming among the Rukai of Wutai village in Taiwan. They observed how several traditional farming practices were continued, such as rotational cropping, intercropping, and fallowing. In addition, this community continues to ensure that its agricultural practices are closely linked to traditional Rukai cultural activities and celebrations. For example, July, which represents the end of the year in the Rukai calendar, is also the end of the harvest season. August, the beginning of the Rukai calendar year, is dedicated to harvest celebrations, including major traditional ceremonies. The authors noted the success and potential of these farming methods in preserving traditional crop diversity and attracting eco- and agritourism, respectively.

THE POTENTIAL FOR ORGANIC FARMING AND AGRITOURISM AMONG INDIGENOUS FARMERS

Although the mountainous nature and distant location of Indigenous farming territory may at first glance appear to be a disadvantage, several factors make these areas ideal for organic farming, agritourism, and ecotourism: 1) Indigenous farmers have a unique culture that can be attractive to both foreign and local tourists; 2) The mountainous areas are ideal for organic farming, which helps reduce soil erosion on steep slopes that characterize mountainous regions (Ba et al., 2018; Yen et al., 2016); and 3) Indigenous traditional farming methods, which make limited use of fertilizers and crop rotation (Ba et al., 2018; Yen et al., 2016), are in line with sustainable methods of cultivation that can support agritourism. Figure 2 illustrates how the traditional characteristics of Indigenous farming can fit well with agritourism values.

COFFEE: AN IDEAL CASH CROP FOR TAIWAN’s INDIGENOUS SMALL FARMERS?

In Taiwan, the coffee industry gained the attention of policymakers after the catastrophic 1999 earthquake (Wang et al., 2019). In counties like Yunlin and Nantou, betel nut and tea cultivation were replaced by coffee (Nicole, 2022). One of the underlying factors behind policymakers promoting coffee cultivation over betel nut, besides discouraging the consumption of the cancer-causing betel nut, was the fact that it protected the soil better. Coffee roots went deeper and were more protective of soils in hilly and mountainous regions; therefore, they were better at protecting against landslides and erosion than betel nut, which has a quite shallow root system (Taiwan Scene, 2022). This fact was emphasized by the massive soil erosion and landslides that resulted from frequent typhoons.

Taiwan’s Indigenous farmers have embraced the cultivation of coffee. As the demand for specialty coffee in Taiwan expanded, Indigenous farmers in Taiwan have adapted to new methods of cultivating coffee, which have often been led by younger generations who have migrated from urban areas back to their rural homelands (Wang et al., 2019). The new coffee industry is also characterized by an emphasis on appealing to the specialty coffee market. As a result, coffee contests have been set up by the state and other NGOs, which are meant to improve the quality of their coffee and to learn innovative ways of marketing coffee to consumers. Indigenous-owned coffee estates such as the Tsou estate in Ali-Shan have grown famous for the numerous awards that they have won for their specialty coffee (Antoine, 2023).

Indigenous farmers have increasingly adopted coffee in Taiwan as a non-traditional crop. The crop has great potential as an agritourism crop, especially if these farms adopt specialty coffee. Specialty coffee as opposed to commercial coffee refers to coffee grown sustainably. This would mean coffee grown on family farms, as opposed to large estates; coffee grown on farms that employ well-paid labor, instead of cheap underpaid labor; and coffee that protects the environment, for example, through limited use of pesticides and fertilizers or organic farming (Pico-Mendoza, 2020). Examples of specialty coffee culture include Costa Rica (Pico-Mendoza, 2020), Rwanda (van Kollenburg & van Weert, 2024), and Taiwan itself (Chang, 2019). Another aspect of specialty coffee refers to its taste. Commercial coffee is often considered to have a bitter taste because it is roasted dark to cover up any inconsistency due to mixed beans and being of inferior quality.

By contrast, in specialty coffee, there is an emphasis on the fruity or floral flavors of coffee, which are far different from the bitter taste profiles that are often associated with commercial coffee. A whole gourmet industry and culture similar to tea or wine has arisen around specialty coffee as a result of this. The specialty coffee industry has a grading system that qualifies different types of coffee according to their taste. The best quality often fetches a high price. For example, in Taiwan, the most expensive coffee went for a remarkable price of US$1,103.4 per kilogram in 2022 (Lin, 2022). Growing specialty coffee requires special training in recognizing its flavors and careful harvesting to ensure that only properly ripened beans are picked.

Although the volumes of specialty coffee can be much smaller than commercial coffee, for small farmers, specialty coffee can be an ideal crop to improve the incomes of small farmers. The volumes of specialty coffee are typically smaller because the crop is labor-intensive. It requires coffee berries to be picked by hand to ensure quality. Also, specialty coffee is often organic, which means limited or no use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. In other words, weeds and pests would have to be removed through intensive manual labor.

The agritourism potential of coffee in Taiwan

The potential for specialty coffee in Taiwan rests on the high demand for coffee in the country and the growing interest among Taiwan consumers in learning about specialty coffee or participating in gourmet coffee culture. The high price of specialty coffee is comparable to the premium prices associated with organic products. Indeed, much of the specialty coffee is already organic. In addition, the coffee farms can serve as agritourism sites, where tourists get the chance to learn about the process of making specialty coffee from bean to brewed cup. The coffee industry in Taiwan has been boosted by the massive demand for coffee among Taiwan’s consumers. For the first time in 2020, Taiwan consumers began consuming more coffee than tea, in a country where tea has been the national beverage for hundreds of years; according to the latest data available, Taiwan customers consumed approximately 2.85 billion cups of coffee a year (USDA, 2021).

The characteristics of specialty coffee also make it suitable for agritourism and ecotourism. Ethical-minded customers would want to see or verify the “sustainable” nature of the specialty coffee that they consume. Agritourism often involves visitors participating in farm activities and learning about the process that goes into the products that they consume. Specialty coffee focuses on tracing every batch or even cup of coffee back to the farm or lot on which it was grown. This trait fits in well with the sustainable motivations of agritourism. On a specialty coffee farm, visitors are allowed the opportunity to witness, verify, and experience firsthand the process of growing and making coffee in a manner that fits their sustainable values.

In addition, the culture around tasting specialty coffee means that visitors could also participate in coffee-tasting educational activities. The unique and complicated tasting profile of coffee invites curiosity and opportunities for education that are comparable to experiential tourism in the wine industry (Govindasamy & Kelley, 2014; Vaquero Piñeiro et al., 2022). Indeed, there is now a growing body of research indicating the potential of specialty coffee in experiential agritourism showing the potential of coffee in developing rural areas (Bowen, 2021). In the case of Taiwan’s Indigenous communities, their unique culture could contribute toward creating a unique agritourism experience centered around coffee farms.

The case study of Kalala: a rejuvenated coffee basket

Kalala, which is a small Indigenous Amis village located in East Taiwan provides an excellent example of the potential of coffee to meet the socioeconomic challenges faced by Indigenous communities in Taiwan as reported by Chang (2019). According to the author, this small rural community has a long history of coffee production; it was a major “coffee basket” during the Japanese colonial period. However, most of the coffee produced by Kalala was exported directly to Japan. The producers were not in any way involved with roasting the coffee, and most of them until recently had not even had a cup of coffee to taste themselves. This gap in knowledge and value between the farmer and his final product is comparable to cocoa production in West Africa, where farmers in countries like the Ivory Coast and Ghana are stuck at the lower end of the value chain and benefit in no way from the production of the high-value chocolate end product (Beg, 2017). After the collapse of Japanese colonial ruling, commercial coffee production in the area all but disappeared. In addition, the community can be described as aging, which means that the majority of its inhabitants are older residents. Many of the younger residents in that community had migrated to industrial hubs located in Changhua, Xizhi, and Taoyuan, seeking jobs in factories and the large industrial estates located there (Chang, 2019).

The community participated in the Rural Rejuvenation Program in 2005. However, they had been disappointed with the results, with many of them complaining that farmers who belonged to the Han majority were the only ones who benefited. After consulting with and taking advice from a team of experts from Dong Hwa University, they broke away from the wider farming group or cooperative associated with the Rejuvenation Program and created their cooperative organization. This organization relied on conventional cooperative methods and traditional Amis farming practices to sustain itself. In their attempts to rejuvenate their community, the Amis farmers revived the production of organic coffee, in which they were faced with several challenges.

As mentioned earlier, many of these farmers had never tasted a cup of coffee themselves; they simply stuck to production. However, the nature of specialty coffee necessitates that the farmer has knowledge of coffee quality as judged by taste. Other problems they faced included: 1) having limited funds to purchase or qualify for organic certification; 2) not having a large enough scale to support larger marketing efforts; 3) the advanced age of many farmers; and 4) rural emigration, with large numbers of working age young people living for better economic opportunities in bigger towns and cities.

These farmers have used a combination of modern methods and traditional Indigenous culture to achieve success in growing organic coffee. For example, they have pushed for organic certification and organized themselves into a farmers’ cooperative. In addition, they also practiced intercropping—a farming method that has been associated with traditional Indigenous farming and which guarantees a constant source of income throughout the year based on the crop that is in season. There has also been an emphasis on marketing and selling directly to consumers instead of relying on middlemen. The agritourism efforts in Kalala appear to be at the beginning stages. The cooperative has arranged for visitors to come to their farm, an initiative that is encouraged by their management of social media sites on Facebook. The visits were designed to “understand how the farm worked . . . to recover the local ecosystem by farming in a more natural way” (Chang, 2019, p. 197).

In short, the case study of Kalala highlights both the challenges and benefits that Indigenous farmers face in both organic farming and organic tourism. It shows that traditional Indigenous farming practices can match the values of organic farming and agritourism. For example, Indigenous farming practices that seek to preserve local plants with little perceived commercial value can be described as preserving biodiversity. In addition, to deal with the farming labor shortage in Kalala, they make use of malaplaiw—a traditional farming practice where labor is shared among farmers. That is, farmers take turns working on each other’s farms during periods of intensive labor, such as the harvesting season.

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Agritourism in Taiwan is a vibrant industry and is supported by the country’s large and dense urban populations, who often use agritourism farms as a break from the busyness of Taiwan’s large cities and an opportunity to interact with farm animals and engage in agricultural activity, such as fruit picking (Liang et al., 2021). The Council of Agriculture (COA, 2021), as of 2020 granted licenses to 486 leisure farms in Taiwan. Taiwan leisure farms are diverse. They include facilities and activities, such as fish farms, fruit orchard farms, animal ranches, bee farms, tea farms, and farm museums. Some of them are quite large, such as the Long Yun Farm, which measures up to 400 ha, whereas others are smaller and are typical of Taiwan’s family farms at less than 2 ha, such as the Forest 18 Leisure Farm. According to Taiwan’s Council of Agriculture (Hsieh & Antoine, 2023; COA, 2021), as of 2019, Taiwan saw 27.8 million tourist journeys to rural and leisure travel destinations; of that number, 77,000 were foreign tourists. In addition, the production value of these travels amounted to NT$10.9 billion (or just over US$341 million). These policies relate to objectives such as 1) regularizing and upgrading the leisure farm industry, 2) developing experiential niche agricultural activities, 3) marketing agritourism to tourists abroad, 4) increasing tourist numbers to local areas, and 5) providing subsidies to support agribusiness enterprises (Hsieh & Antoine, 2021).

Agritourism among Indigenous farmers in Taiwan has tremendous potential; however, this potential has yet to be fully exploited. Several factors support the agritourism potential for Indigenous communities: 1) Indigenous farming practices are often sustainable and eco-friendly; 2) Indigenous farming is community-based farming, which supports the needs of these communities; 3) Indigenous farming practices provide the ideal opportunity for educational activities that are typical of agritourism. Indigenous traditional farming often relies on permaculture, that is, an approach to farming that seeks to emulate natural ecosystems (Chang, 2019). This can be seen in the kind of agroforestry system practiced by the Tayal Indigenous community in Hsinchu (Yen & Chen, 2016). In addition, Indigenous communities practice other eco-friendly farming strategies such as intercropping, rotation, organic farming, and fallowing (i.e., allowing the land to rest for a certain period after harvest). All these practices are in line with the sustainability ethic that is often associated with agritourism.

Specialty coffee is an ideal crop for organic farming and agritourism. It has recently attracted attention because of its association with sustainability and the issue of traceability. Most commercial coffee exploits cheap labor and supports massive corporations, whereas specialty coffee is often seen as promoting local farmers and supporting local communities, who get paid higher wages because of the premium prices associated with specialty coffee. Also, specialty coffee belongs to a gourmet culture that can attract much curiosity and opportunities for learning in the context of agritourism. Lastly, because of the emphasis on sustainability, specialty coffee often relies on organic farming. Coffee was historically grown in Indigenous areas, and this provides unique opportunities for these Indigenous folks.

One of the core principles of agritourism and organic farming is community support (Sulistyowati, 2023). Because Indigenous communities are often rural people who suffer from problems like an aging population and high levels of unemployment, agritourism would be ideal. Agritourism has the potential to support farmers directly by allowing them to sell their produce directly. The increased economic opportunities may improve employment and even induce farmers to return from larger industrial centers to their hometowns. This was the case in Kalala, where aging farmers left the big cities when they were no longer of working age to return home to Kalala to take up organic coffee farming (Chang, 2019). Regarding educational activities, the process of growing organic crops provides an opportunity for visitors to learn and participate in sustainable farming practices.

Although there is much potential for organic farming within the context of agritourism among Indigenous communities, policy support from the government is required to fulfill said potential. For example, the cost of certification can be prohibitive, which means that farmers often struggle to obtain the certification necessary to sell their produce at premium prices. This is somewhat ironic considering that poor farmers typically farm without chemical pesticides and fertilizers because they are unable to afford them (Parrott et al., 2006). Subsidies to reduce the cost of certification for farmers would be helpful in that regard. Moreover, although Indigenous communities may have ideal characteristics, such as mountainous scenery and other picturesque rural landscapes, they require help with marketing to make these locations known to the public. Policymakers could think of providing farmers with the proper training in marketing.

Another major issue facing rural Indigenous communities and Taiwan in general is the labor shortage in the agricultural sector due to the aging population phenomenon (Chen, 2023). The remaining farmers in Taiwan are both too old and too few. This shortage of farmers poses a serious challenge to creating a viable agricultural industry in small rural Indigenous communities. Taiwan for other sectors of its economy, such as manufacturing, relies on foreign labor. Such a solution could be considered for its farming sector. Another long-term solution would involve coming up with policies to make organic farming and agritourism more attractive to young Indigenous people residing in the countryside. Making credit available to undertake modern farm enterprises would be one way of attracting these young folks back to their communities.

REFERENCES

Antoine, M. (2023, October). Coffee so green. https://bluedotliving.com/coffee-so-green/

Ba, Q.-X., Lu, D.-J., Kuo, W.H.-J., & Lai, P.-H. (2018). Traditional Farming and Sustainable Development of an Indigenous Community in the Mountain Area—A Case Study of Wutai Village in Taiwan. Sustainability, 10, 3370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103370

Bayrak, M.M. (2022). Does Indigenous tourism contribute to Indigenous resilience to disasters? A case study on Taiwan's highlands. Progress in Disaster Science, 14, 100220.

Bayrak, M. M., Hung, L. S., & Hsu, Y. Y. (2023). Living with typhoons and changing weather patterns: Indigenous resilience and the adaptation pathways of smallholder farmers in Taiwan. Sustainability Science, 18(2), 951–965.

Beg, M.S., Ahmad, S., Jan, K., & Bashir, K. (2017). Status, supply chain and processing of cocoa-A review. Trends in food science & technology, 66, 108–116.

Bowen, R. (2021). Cultivating coffee experiences in the Eje Cafetero, Colombia. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(3), pp. 328-339. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-08-2020-0184

Chang, C.W. (2019). An Alternative Agricultural Space in an Indigenous Community: Kalala, Taiwan. In: Leimgruber, W., Chang, Cy. (eds.), Rural Areas Between Regional Needs and Global Challenges. Perspectives on Geographical Marginality, vol 4. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04393-3_11

Chen, C.H. (2023). Taiwan’s Rapidly Aging Population: A Crisis in the Making? Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

Council of Agriculture [COA]. (n.d.) Overview. COA. https://eng.moa.gov.tw.

Diamond, J. (2000). Taiwan's gift to the world. Nature, 403, 709–710. https://doi.org/10.1038/35001685

Govindasamy, R. and Kelley, K. (2014). Agritourism consumers’ participation in wine tasting events: An econometric analysis. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 26(2), pp. 120-138. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-04-2013-0011

Hsieh, C. M., & Antoine, M. The Role of Agritourism in Taiwan's Rural Revitalization Strategy The Role of Agritourism in Taiwan's Rural Revitalization Strategy. FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform.

Huang, S. M., Che-Hao, H., & Chang, Y. H. (2021). The paradox of cultivating community resiliency: Re-agrarianisation and De-peasantisation of indigenous farmers in Taiwan. Journal of Rural Studies, 83, 96–105.

Kang, P. (2003). A Brief Note on the Possible Factors Contributing to the Large Village Size of the Siraya in the Early Seventeenth Century. In Leonard Blusse (ed.), Around and About Formosa. Taipei, SMC Publishing. pp. 111–127.

Liang, A. R. D., Hsiao, T. Y., Chen, D. J., & Lin, J. H. (2021). Agritourism: Experience design, activities, and revisit intention. Tourism Review, 76(5), 1181-1196.

Linton, A. (2008). A niche for sustainability? Fair labor and environmentally sound practices in the specialty coffee industry. Globalizations, 5(2), 231–245.

Liu, Shang-Yu, Chen-Ying Yen, Kuang-Nan Tsai, & Wei-Shuo Lo. (2017). A Conceptual Framework for Agri-Food Tourism as an Eco-Innovation Strategy in Small Farms. Sustainability 9(10), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101683

Nicole, L. (2022, September 19). Wake up to high-scoring coffees from Taiwan. Coffee Knowledge Hub. https://coffeeknowledgehub.com/it/news/wake-up-to-high-scoring-coffees-from-taiwan

Parrott, N., Olesen, J. E., & Høgh-Jensen, H. (2006). Certified and non-certified organic farming in the developing world. In Global development of organic agriculture: Challenges and prospects (pp. 153-179). Wallingford UK: CABI Publishing.

Pico-Mendoza, J., Pinoargote, M., Carrasco, B., & Limongi Andrade, R. (2020). Ecosystem services in certified and non-certified coffee agroforestry systems in Costa Rica. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44(7), 902-918.

Sulistyowati, C. A., Afiff, S. A., Baiquni, M., & Siscawati, M. (2023). Challenges and potential solutions in developing community supported agriculture: a literature review. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 47(6), 834-856.

Taiwan Scene. (January 18, 2022). How Taiwanese Coffee is Stimulating Sustainable Farming. Taiwan Scene.

https://taiwan-scene.com/how-taiwanese-coffee-is-stimulating-sustainable....

USDA (2021). Opportunities for US Coffee Percolate in Taiwan Brewing Market. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Opportunities%20for%20US%20Coffee%20Percolate%20in%20Taiwan%20Brewing%20Market_Taipei%20ATO_Taiwan_04-27-2021#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20recent%20survey,growth%20rate%20of%2020%20percent.

van Kollenburg, G., & van Weert, P. (2024). Coffee, climate, community: A holistic examination of specialty coffee supply chains in Rwanda (in press). Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3000

Wang, M. J., Chen, L. H., Su, P. A., & Morrison, A. M. (2019). The right brew? An analysis of the tourism experiences in rural Taiwan's coffee estates. Tourism management perspectives, 30, 147-158. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2211973619300200

Vaquero Piñeiro, M., Tedeschi, P., & Maffi, L. (2022). Italy Tasting: Wine, Tourism, and Landscape. In A History of Italian Wine: Culture, Economics, and Environment in the Nineteenth through Twenty-First Centuries (pp. 191-231). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Yen, A. C., & Yin-An, C. (2016). Agroforestry as sustainable agriculture: an observation of Tayal indigenous people’s collective action in Taiwan. The International Journal of Environmental Sustainability, 13(1), 1.

Yu, C.-Y. An Application of Sustainable Development in Indigenous People’s Revival: The History of an Indigenous Tribe’s Struggle in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093259