ABSTRACT

Rice is the staple food of Malaysian people. Malaysia produces more than 1.55 million tons of rice yearly, equivalent to 73% of the local requirement. The demand for rice is projected to increase due to the increase in population. However, rice production is decreasing every year. Rice production has been reduced from 1.80 million tons in 2017 to 1.51 million tons in 2021, and is projected to be further reduced if the government does not take any special action. Several factors contributed to the downtrend of paddy production in Malaysia, including reducing land areas and moderate adoption of mechanization technology. At the same time, farm productivity has decreased from 4.7 ton/ha to 3.5 ton/ha. Human factors are also critical in contributing to low farm productivity. This article highlights the sociological factors contributing to the yield gap in paddy production. A case study was carried out in the IADA Batang Lupar, Sarawak, one of the granary areas in Malaysia. Structure, process, and culture contribute to farmers' yield gap. Structure refers to infrastructure, process refers to agriculture practices, and culture determines the attitude of the farmers. Farmers’ agricultural knowledge is one of the essential factors in cultivating paddy and will determine the productivity of the farm. Knowledgeable farmers will follow good agriculture practices and protocols. The advice and assistance from the extension agents help farmers manage their farms through good agricultural practices. Subsidies received and used by the farmers also increased the yield. The more subsidies received and used, the higher the yield. Farm monitoring and maintenance also contributed to farm productivity. The farmers' attitude toward information and good agriculture practices is a determinant factor that must be addressed. Besides the infrastructure and capital, human factors are crucial in determining Malaysia's paddy production.

Keywords: Sociological issues, rice production, farm productivity, policy

INTRODUCTION

Rice is the staple food of Malaysian people. Every year, Malaysian people consume more than 2.4 million tons of rice and rice-based products such as vermicelli, and confectionery. The primary source of rice supply is paddy fields cultivated by agricultural entrepreneurs. In 2021, Malaysia produced more than 2.343 million tons of paddy that was converted to 1.512 million tons of rice. Rice production can only supply approximately 73% of the population's needs. Importing rice from Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, India, and other countries covers the need for more supply. In 2021, Malaysia imported more than 1.22 million tons of rice of various varieties, such as basmati, fragrant rice, and Japonica.

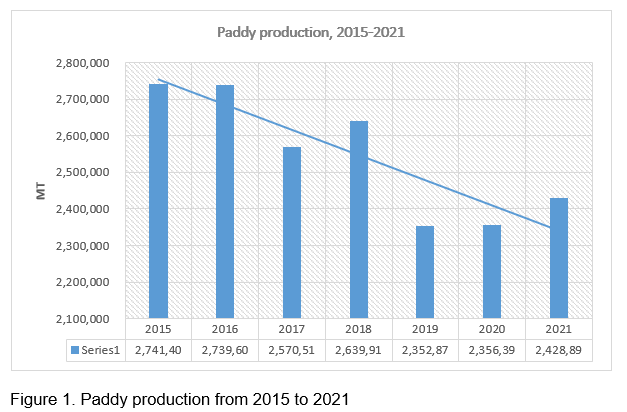

Malaysia's population is projected to increase from 32.8 million in 2021 to more than 38.1 million by 2030. Malaysia aims to become a developed and sustainable food secure country. The increase in population requires an additional supply of rice. Malaysia will face a threat to food security if the productivity of the paddy crop does not change. Statistics from the Department of Agriculture show that rice production has declined continuously since 2000. The paddy production has dropped from 2.74 million tons in 2015 to 2.43 million tons in 2021, a reduction of around 11.3% within six years. Production is expected to continue to decline in the coming years unless there is an action from the government. The decline in rice production is due to several factors, such as the reduction in cultivation areas, the effects of climate change, and a decrease in productivity.

The productivity of paddy production is currently low compared to the production target in the National Agrofood Policy 1.0, which is 5.0 ton/ha. Farm productivity has declined from 4.02 ton/ha in 2015 to 3.75 ton/ha in 2021. Among the causes of the decline in rice production productivity is the need for more technology and machinery in the production system. In 2018, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (MAFI) recorded that 86.2% of rice farmers in paddy granary areas own machinery worth less than RM10,000.00 (US$2,222.00). This situation shows that most agricultural entrepreneurs still use less farm machinery or rely on machinery rented from service providers. A study by MARDI showed that approximately 64% of agricultural entrepreneurs know the importance of paddy cultivation technology and have knowledge about the technology. However, 34% of them think that the price of paddy cultivation technology is high and is an obstacle for them to use it.

The country's rice industry is in a critical state and needs a new strategy to transform into a more dynamic and progressive one. Malaysia will experience a significant shortage of rice supply and will have to rely on external sources if the government does not implement new initiatives. The situation could be exacerbated in the event of a food crisis where supplier countries refuse to sell rice to Malaysia, which could jeopardize the country's food security. The rice industry needs government intervention and a new strategy involving all industry players, such as agribusinesses, regional farmers' organizations, machinery service providers, and rice manufacturers.

Despite many support programs, incentives, and subsidies provided by the government, the performance of the paddy industry could be much better. This article discusses issues and challenges Malaysia's rice industry faces from a sociological perspective. It highlights the human factors contributing to Malaysia's low paddy farm productivity. The analysis presented in this article is based on a study by MARDI in 2020.

PADDY PRODUCTION

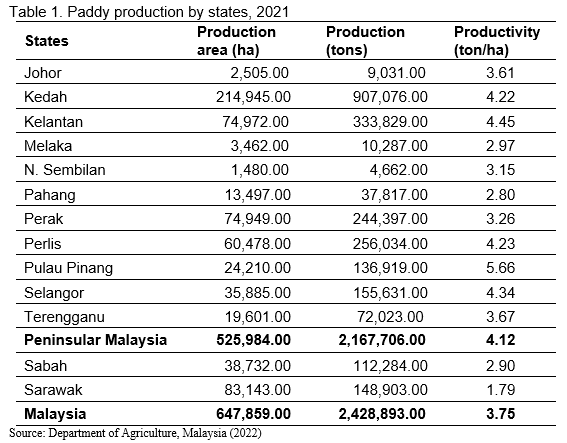

After oil palm and rubber, paddy is Malaysia's third most important cultivated crop. Malaysia acquired more than 647,859 hectares of paddy, involving more than 322,830 farmers in 2021. Paddy is cultivated in all states, as presented in Table 1. Malaysia produces more than 2.43 million tons of paddy yearly, equivalent to around 1.68 million tons of rice.

According to Table 1, the largest production area for paddy cultivation is in Kedah, followed by Sarawak, Kelantan, and Perak. More than 33.17% of the cultivation areas are in Kedah. Kedah is known as Malaysia's Rice Bowl. Sarawak is one of Malaysia's states located in Borneo Island. This state opened more than 83,143 hectares of land for paddy cultivation. However, Table 1 shows that the farm productivity in Sarawak is the lowest, amounting to only 1.79 ton/ha. The low farm productivity in Sarawak has reduced the national average of paddy production in Malaysia.

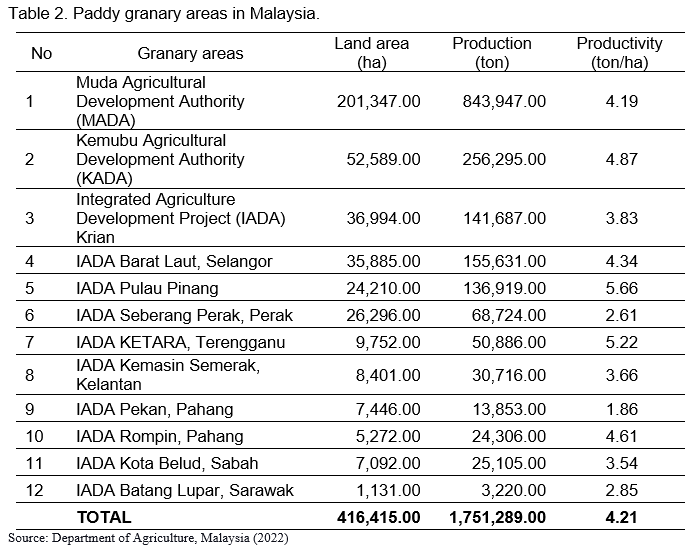

Paddy is mainly cultivated in granary areas. Around 64% or 416,415 hectares of paddy is cultivated in the granary areas, while the balance is outside these areas. Currently, there are twelve main paddy granary areas in Malaysia, which can be regarded as the nation's rice bowl and food security. The establishment of main granary areas under the National Agricultural Policy (NAP) of 1984–1991 was purposely reserved as designated wetland paddy areas. The granary areas received various support programs from the government and, in general, are more advanced in the production system. The current paddy granary areas are presented in Table 2.

MADA, located in Kedah, is Malaysia's largest granary area, with more than 201,347 hectares. This area also produces the most significant quantity of paddy every year. For example, MADA produced more than 843,947 tons or 48.19% of paddy in 2021. KADA produced 256,295 tons of paddy, followed by IADA Barat Laut in Selangor and IADA Krian in Perak. On the other hand, IADA Batang Lupar is the smallest granary in Malaysia, with a total land area of 1,131 hectares. The farm productivity of the Batang Lupar IADA is 2.85 ton/ha. The low farm productivity in Sarawak, especially in the granary area, resulted in low self-sufficiency level (SSL) of rice in the state. The Sarawak state only produces around 36% of its rice, and the balance must be imported from neighboring countries.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES IN PADDY PRODUCTION

Malaysia has a very comprehensive National Agro-food Policy for spearheading the agriculture sector. However, the performance of the sector in general is still discouraging. Most industries show a downward trend in production, including the paddy industry. The performance of paddy production is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that paddy production has declined continuously from 2.74 million tons in 2015 to 2.43 million tons in 2021. The downward trend indicates the discouraging performance of the paddy industry in Malaysia. The downward trend is expected to continue unless there is direct intervention from the stakeholders, including the departments and agencies, the industry players, and the farmers.

MARDI has conducted a study to understand the sociological factors contributing to this trend. The study focuses on the farmers' sociological aspects in the granary areas. The following section presents a case study on the issues of paddy production in one of the granary areas in Malaysia, the Integrated Agriculture Development Project (IADA), Batang Lupar, in Sarawak.

Case study in IADA Batang Lupar, Sarawak

The concept of integrated agricultural development, known as the Integrated Agricultural Development Project (IADA), was started in 1965 and spread out throughout almost the country. The integrated agricultural development approach prioritizes incorporating all efforts and activities between various departments and agencies under the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia (as well as the need for other ministries agencies). This integrated approach is needed to provide agricultural infrastructure facilities and related support services. The objectives of IADA are to:

l Increase productivity and maximize the income of the target group so that it can reduce income differences with other sectors;

l Modify the agricultural sector so that the production system is efficient, saving human energy, and can compete with domestic and foreign markets;

l Develop the target group to be a disciplined, self-reliant, progressive, and entrepreneurial society; and

l Increase the average production of paddy yield to 6.5 tons/ha per season

The scope of the IADA implementation includes the development of agricultural infrastructure and developing sub-sectors of the crop, fisheries, and livestock "in situ." The main functions of the IADA are:

l Develop agricultural infrastructure, especially irrigation and drainage systems for specific agricultural areas;

l Strengthen and expand agricultural support and agricultural management services;

l Coordinate advisory services and development services to target groups through human development/training programs; and

l Strengthen the services of implementation agencies in the development of agricultural and farmers institutions.

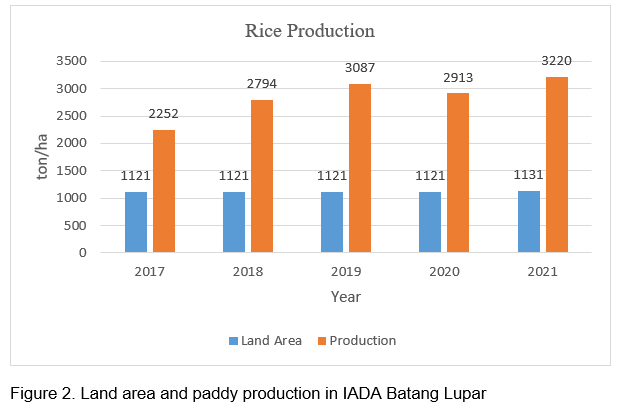

IADA Batang Lupar is one of the twelve granary areas in Malaysia. This granary area is located in Sri Aman, Sarawak. IADA Batang Lupar is a new gazette granary in addition to the existing granaries. The rice cultivation area in IADA Batang Lupar in 2021 was 1,131 ha, an increase from 1,121 ha in 2020 (Figure 2).

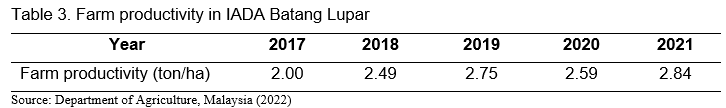

Figure 2 shows that between 2017 and 2021 paddy production at the IADA Batang Lupar did not differ significantly. The paddy cultivation area at IADA Batang Lupar was the same in 2017 and 2020 at 1,121 hectares, but there was a 10.5% increase in production in 2021 compared to the previous year. The paddy production is slightly increased from 2,252 tons in 2017 to 3,220 tons in 2021. The farm productivity of IADA Batang Lupar is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the average farm productivity at IADA Batang Lupar has slightly increased from 2.00 ton/ha in 2017 to 2.84 ton/ha in 2021. However, the farm productivity is below the target of 6 ton/ha. The farm productivity in IADA Batang Lupar is also one of the lowest among the granary areas in Malaysia.

To understand why the productivity is relatively low, three sociological scopes were look upon to factor that may influence the productivity are: the structure, process, and culture. The structure refers to the infrastructures and facilities provided by the government. The process refers to the activities carried out by farmers during the production processes. Culture determines the ability of farmers to perform the production process according to the production manual provided by the Department of Agriculture. The dimensions of the variable are as follows:

|

Structure

|

Process

|

Culture

|

- Location of farm plot near the source of irrigation.

|

- Farm maintenance and monitoring by farmers

|

- Skill gained from attending the course

|

|

|

- Farm activities according to planting guideline

|

- Trust to the source of information

|

- Participation in the training provided by government agencies

|

- The ability to solve the problem

|

- The effectiveness of the information provided by government agencies

|

|

|

|

|

- Government agencies involvement

|

|

|

- Rice check or cultivation manual

|

|

|

Out of all these dimensions, the study revealed that factors that contributed to the yield gap among farmers in IADA Batang Lupar are as follows:

Structure

- Farmers who attended or participated in courses or training provided by government agencies produce higher yields. The higher yield is associated with the knowledge of the farmers.

- However, only 9.5% of farmers in Batang Lupar attended training courses organized by government agencies such as the IADA and the Department of Agriculture. As a result, most of the farmers are lacking in agriculture knowledge. The lack of knowledge has led to bad operational practices and low farm yield.

- The government provided eleven types of subsidies: compound fertilizers, urea, additional fertilizers, pesticides, seed germination booster, foliar spray fertilizers, crop tonics, organic fertilizers, lime, wages, plowing, and price subsidy. However, most farmers in IADA Batang Lupar received only five types of subsidies, including compound fertilizers, urea, additional fertilizers, pesticides, and organic fertilizers. The government has changed the policies in 2017 where only selected subsidies were given to farmers, and it somehow related to subsidies for farmers in IADA Batang Lupar. The Department of Agriculture analyzed the input requirements in granary areas and proposed that subsidies should be given to the farmers in that particular areas. In other words, different granary areas will receive different types of subsidies. The lack of subsidies may result in low farm yield.

- Additional advisory assistance from government agencies such as MARDI, DOA, and Farmers Organization Authority contributed to higher yields. The more the extension officers visited and discussed with the farmers, the more their farm yielded. This finding shows the importance of extension agents in guiding farmers.

Process

- Farm monitoring is critical in paddy production. It involves many activities, from land preparation to harvesting the yield, such as plowing the land, maintaining the water lever, weeding the grass, controlling pests and diseases, and post-harvest handling. In general, farmers in IADA Batang Lupar do less farm maintenance. On average, they go three times a week to their farm. Lack of monitoring leads to pests and diseases attacks that cannot be identified early.

- Farmers need to follow the cultivation manual suggested by the DOA. The planting guidelines farmers do not follow perfectly are seed preparation, soil preparation, tillage, water management, weed management, and pest management. This weakness contributes to low yields.

- The farmers’ inability to solve capital costs, labor, input, diseases, and pests also reduced the yield. Farmers in Batang Lupar are small-scale farmers and need more capital to invest in modern technology or mechanization. Thus, they applied traditional methods that could be more efficient and productive.

- The low adoption of modern technology also contributed to low-yield.

Culture

- Culture is developed when a person performs the same habit continuously. When a farmer follows the cultivation practices suggested by a manual provided by the Department of Agriculture, it becomes the Culture. A good culture will result in good performance.

- Only 9.5% of farmers attended courses organized by the agencies. Thus, farmers do not benefit from the organized courses. As a result, only some farmers in the IADA Batang Lupar carried out the cultivation practice as suggested in the manual. Good agriculture is different from the practice of farmers in IADA Batang Lupar. As a result, they produce little yield.

- Farmers also very seldom use information provided by government agencies because they need help in understanding how to transform the information into action. As a result, they need to pay more attention to the information provided by the officers. In other words, training the trainers to convey the knowledge information to the farmers is necessary.

- As good agriculture practice is not the culture of the farmers, the study shows that the subsidies provided by the government do not significantly impact the farm productivity in IADA Batang Lupar.

- As a result, the paddy production does not improve the socioeconomic of the farmers in IADA Batang Lupar.

The case study in the IADA Batang Lupar represents the real issues and challenges in paddy production in Malaysia. Human factors are among the main contributors to low production productivity. The government has spent billions of Malaysian Ringgit to transform the paddy industry into a more dynamic, modern, and progressive industry. Besides the infrastructure and technology application, the government must address the sociological factors that could improve the industry.

WAY FORWARD

The focus of the agricultural sector in the 12th Malaysian Economic Development Plan is to increase the productivity and food security. The increase in rice production is closely related to the level of technology use, the efficiency of resource use, and the attitude of farmers. The government has allocated various incentives and subsidies to paddy farmers to support productivity improvement programs as a strategy to increase production throughout the country. Malaysia is worried that the significant dependence on rice supply sources can cause food insecurity and significantly impact the harmony of the people.

The government targeted that by 2030, total rice production will reach 2.32 million tons, with an increase of 53.6% compared to 1.51 million tons in 2019 and a target compounded average growth rate (CAGR) of 4.89%. The total production increase will contribute to the goal set, SSL 80.00%. The average yield of rice paddy per unit of paddy field area will be increased to 5.3 ton/ha compared to the current average yield of 3.5 ton/ha (2019), with a CAGR of 3.84%, to achieve this target.

In the next ten years, the productivity of the paddy and rice sub-sector will be boosted through better efficiency in using natural resources and improving the income levels of industry drivers across the value chain of this sub-sector, especially for the paddy fields. In addition, through a more conducive business environment, the competitiveness and capabilities of this sub-sector will be improved. This aspiration has been translated into five strategies to be implemented in the next ten years. These strategies consider the issues and challenges the paddy and rice sub-sector faces. The five strategies identified are:

- Increase productivity through better management of land and water use. Emphasis is placed on two primary natural resources in rice cultivation: land and water, especially in increasing resource use efficiency in achieving higher productivity;

- Utilize the potential of special local rice varieties. This strategy intends to develop the segment local variety specialty rice to give diversity in the choice of varieties for rice;

- Promote, encourage, train, and nurture the young generation to be involved in the paddy and rice sub-sector. Refine the current input and output assistant mechanism for rice farmers to encourage them to optimize agricultural operations based on knowledge and their own experience;

- Restructure existing financial assistance towards empowering producers in making business decisions and encouraging the participation of private operators in all scales across the value chain of the rice sub-sector; and

- Involve the participation of more private sector drivers along the value chain. Provide exposure and increase knowledge regarding the paddy and rice sub-sector for generations of young people who will be the driving force of the industry in the future.

The government also aspires to transform Sabah and Sarawak into new sources of rice production. More land areas will be opened and transformed into rice granary areas. The government plans to develop more than 50,000 ha of land in Sabah and Sarawak as Malaysia's new source of paddy production. In a short-term plan, the government is developing 4,839 ha of land in Sabah and Sarawak for paddy cultivation, which is 2,159 ha of land in Sabah, namely in Beluran and Kota Belud, and 2,680 ha in Batang Lupar in Sarawak.

The government will provide funds for improving infrastructure, including irrigation systems, farm roads, paddy mills, etc. To support paddy cultivation in the country, the government allocated RM1.57 (US$0.39) billion in the 2021 Budget to support the industry, including the legal paddy seed incentive, federal government paddy fertilizer scheme, paddy production incentive scheme, fertilizer scheme, pesticides for hill paddy and paddy price subsidy scheme. At the same time, the application of modern farm mechanization technologies will be intensified.

Quite recently, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MAFS) plans to boost the national rice production's Self-Sufficient Levels (SSL) to 80% within the 12th Malaysia Plan period. The ministry has launched a new rice cultivation approach called the Large-Scale Smart Paddy Cultivation (SMART SBB) initiative to achieve this target. The initiative unites paddy fields through contractual or rental agriculture via a management system that optimizes available resources for increased farming effectiveness and post-harvest production. The program aims to raise the average yield per hectare from the average current production of 3.5 ton/ha in 2019 to 7.0 ton/ha under the 12th Malaysian Plan. Technology like the Internet of Things (IoT) and economies of scale will uplift production per hectare. The new initiative has the potential to change the industry landscape to guarantee a secure and consistent national food supply.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture, Malaysia (2022). Booklet Statistics Tanaman (Sub-sektor Tanaman Makanan). Jabatan Pertanian Semenanjung Malaysia, Putrajaya.

Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industri (2020). Dasar Agromakanan Negara 2021-2030 (DAN 2.0):Pemodenan Agromakanan: Menjamin Masa Depan Sekuriti Makanan Negara

Zainol Abidin, A.Z, Sukimi, M.F, Engku Ariff, E. El, Ahmad Sobri A., Abdul Wahab, M.A.M and Suratman, N.H. (2020). Kajian Sosiologi pesawah padi inbred di kawasan IADA Batang Lupar, Sarawak dan IADA Kota Belud, Sabah. Laporan Kajian Sosioekonomi 2020. MARDI, Persiaran MARDI-UPM, 43400 Serdang.

Sociological Issues and Challenges of Rice Production in Malaysia

ABSTRACT

Rice is the staple food of Malaysian people. Malaysia produces more than 1.55 million tons of rice yearly, equivalent to 73% of the local requirement. The demand for rice is projected to increase due to the increase in population. However, rice production is decreasing every year. Rice production has been reduced from 1.80 million tons in 2017 to 1.51 million tons in 2021, and is projected to be further reduced if the government does not take any special action. Several factors contributed to the downtrend of paddy production in Malaysia, including reducing land areas and moderate adoption of mechanization technology. At the same time, farm productivity has decreased from 4.7 ton/ha to 3.5 ton/ha. Human factors are also critical in contributing to low farm productivity. This article highlights the sociological factors contributing to the yield gap in paddy production. A case study was carried out in the IADA Batang Lupar, Sarawak, one of the granary areas in Malaysia. Structure, process, and culture contribute to farmers' yield gap. Structure refers to infrastructure, process refers to agriculture practices, and culture determines the attitude of the farmers. Farmers’ agricultural knowledge is one of the essential factors in cultivating paddy and will determine the productivity of the farm. Knowledgeable farmers will follow good agriculture practices and protocols. The advice and assistance from the extension agents help farmers manage their farms through good agricultural practices. Subsidies received and used by the farmers also increased the yield. The more subsidies received and used, the higher the yield. Farm monitoring and maintenance also contributed to farm productivity. The farmers' attitude toward information and good agriculture practices is a determinant factor that must be addressed. Besides the infrastructure and capital, human factors are crucial in determining Malaysia's paddy production.

Keywords: Sociological issues, rice production, farm productivity, policy

INTRODUCTION

Rice is the staple food of Malaysian people. Every year, Malaysian people consume more than 2.4 million tons of rice and rice-based products such as vermicelli, and confectionery. The primary source of rice supply is paddy fields cultivated by agricultural entrepreneurs. In 2021, Malaysia produced more than 2.343 million tons of paddy that was converted to 1.512 million tons of rice. Rice production can only supply approximately 73% of the population's needs. Importing rice from Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, India, and other countries covers the need for more supply. In 2021, Malaysia imported more than 1.22 million tons of rice of various varieties, such as basmati, fragrant rice, and Japonica.

Malaysia's population is projected to increase from 32.8 million in 2021 to more than 38.1 million by 2030. Malaysia aims to become a developed and sustainable food secure country. The increase in population requires an additional supply of rice. Malaysia will face a threat to food security if the productivity of the paddy crop does not change. Statistics from the Department of Agriculture show that rice production has declined continuously since 2000. The paddy production has dropped from 2.74 million tons in 2015 to 2.43 million tons in 2021, a reduction of around 11.3% within six years. Production is expected to continue to decline in the coming years unless there is an action from the government. The decline in rice production is due to several factors, such as the reduction in cultivation areas, the effects of climate change, and a decrease in productivity.

The productivity of paddy production is currently low compared to the production target in the National Agrofood Policy 1.0, which is 5.0 ton/ha. Farm productivity has declined from 4.02 ton/ha in 2015 to 3.75 ton/ha in 2021. Among the causes of the decline in rice production productivity is the need for more technology and machinery in the production system. In 2018, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (MAFI) recorded that 86.2% of rice farmers in paddy granary areas own machinery worth less than RM10,000.00 (US$2,222.00). This situation shows that most agricultural entrepreneurs still use less farm machinery or rely on machinery rented from service providers. A study by MARDI showed that approximately 64% of agricultural entrepreneurs know the importance of paddy cultivation technology and have knowledge about the technology. However, 34% of them think that the price of paddy cultivation technology is high and is an obstacle for them to use it.

The country's rice industry is in a critical state and needs a new strategy to transform into a more dynamic and progressive one. Malaysia will experience a significant shortage of rice supply and will have to rely on external sources if the government does not implement new initiatives. The situation could be exacerbated in the event of a food crisis where supplier countries refuse to sell rice to Malaysia, which could jeopardize the country's food security. The rice industry needs government intervention and a new strategy involving all industry players, such as agribusinesses, regional farmers' organizations, machinery service providers, and rice manufacturers.

Despite many support programs, incentives, and subsidies provided by the government, the performance of the paddy industry could be much better. This article discusses issues and challenges Malaysia's rice industry faces from a sociological perspective. It highlights the human factors contributing to Malaysia's low paddy farm productivity. The analysis presented in this article is based on a study by MARDI in 2020.

PADDY PRODUCTION

After oil palm and rubber, paddy is Malaysia's third most important cultivated crop. Malaysia acquired more than 647,859 hectares of paddy, involving more than 322,830 farmers in 2021. Paddy is cultivated in all states, as presented in Table 1. Malaysia produces more than 2.43 million tons of paddy yearly, equivalent to around 1.68 million tons of rice.

According to Table 1, the largest production area for paddy cultivation is in Kedah, followed by Sarawak, Kelantan, and Perak. More than 33.17% of the cultivation areas are in Kedah. Kedah is known as Malaysia's Rice Bowl. Sarawak is one of Malaysia's states located in Borneo Island. This state opened more than 83,143 hectares of land for paddy cultivation. However, Table 1 shows that the farm productivity in Sarawak is the lowest, amounting to only 1.79 ton/ha. The low farm productivity in Sarawak has reduced the national average of paddy production in Malaysia.

Paddy is mainly cultivated in granary areas. Around 64% or 416,415 hectares of paddy is cultivated in the granary areas, while the balance is outside these areas. Currently, there are twelve main paddy granary areas in Malaysia, which can be regarded as the nation's rice bowl and food security. The establishment of main granary areas under the National Agricultural Policy (NAP) of 1984–1991 was purposely reserved as designated wetland paddy areas. The granary areas received various support programs from the government and, in general, are more advanced in the production system. The current paddy granary areas are presented in Table 2.

MADA, located in Kedah, is Malaysia's largest granary area, with more than 201,347 hectares. This area also produces the most significant quantity of paddy every year. For example, MADA produced more than 843,947 tons or 48.19% of paddy in 2021. KADA produced 256,295 tons of paddy, followed by IADA Barat Laut in Selangor and IADA Krian in Perak. On the other hand, IADA Batang Lupar is the smallest granary in Malaysia, with a total land area of 1,131 hectares. The farm productivity of the Batang Lupar IADA is 2.85 ton/ha. The low farm productivity in Sarawak, especially in the granary area, resulted in low self-sufficiency level (SSL) of rice in the state. The Sarawak state only produces around 36% of its rice, and the balance must be imported from neighboring countries.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES IN PADDY PRODUCTION

Malaysia has a very comprehensive National Agro-food Policy for spearheading the agriculture sector. However, the performance of the sector in general is still discouraging. Most industries show a downward trend in production, including the paddy industry. The performance of paddy production is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that paddy production has declined continuously from 2.74 million tons in 2015 to 2.43 million tons in 2021. The downward trend indicates the discouraging performance of the paddy industry in Malaysia. The downward trend is expected to continue unless there is direct intervention from the stakeholders, including the departments and agencies, the industry players, and the farmers.

MARDI has conducted a study to understand the sociological factors contributing to this trend. The study focuses on the farmers' sociological aspects in the granary areas. The following section presents a case study on the issues of paddy production in one of the granary areas in Malaysia, the Integrated Agriculture Development Project (IADA), Batang Lupar, in Sarawak.

Case study in IADA Batang Lupar, Sarawak

The concept of integrated agricultural development, known as the Integrated Agricultural Development Project (IADA), was started in 1965 and spread out throughout almost the country. The integrated agricultural development approach prioritizes incorporating all efforts and activities between various departments and agencies under the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia (as well as the need for other ministries agencies). This integrated approach is needed to provide agricultural infrastructure facilities and related support services. The objectives of IADA are to:

l Increase productivity and maximize the income of the target group so that it can reduce income differences with other sectors;

l Modify the agricultural sector so that the production system is efficient, saving human energy, and can compete with domestic and foreign markets;

l Develop the target group to be a disciplined, self-reliant, progressive, and entrepreneurial society; and

l Increase the average production of paddy yield to 6.5 tons/ha per season

The scope of the IADA implementation includes the development of agricultural infrastructure and developing sub-sectors of the crop, fisheries, and livestock "in situ." The main functions of the IADA are:

l Develop agricultural infrastructure, especially irrigation and drainage systems for specific agricultural areas;

l Strengthen and expand agricultural support and agricultural management services;

l Coordinate advisory services and development services to target groups through human development/training programs; and

l Strengthen the services of implementation agencies in the development of agricultural and farmers institutions.

IADA Batang Lupar is one of the twelve granary areas in Malaysia. This granary area is located in Sri Aman, Sarawak. IADA Batang Lupar is a new gazette granary in addition to the existing granaries. The rice cultivation area in IADA Batang Lupar in 2021 was 1,131 ha, an increase from 1,121 ha in 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows that between 2017 and 2021 paddy production at the IADA Batang Lupar did not differ significantly. The paddy cultivation area at IADA Batang Lupar was the same in 2017 and 2020 at 1,121 hectares, but there was a 10.5% increase in production in 2021 compared to the previous year. The paddy production is slightly increased from 2,252 tons in 2017 to 3,220 tons in 2021. The farm productivity of IADA Batang Lupar is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the average farm productivity at IADA Batang Lupar has slightly increased from 2.00 ton/ha in 2017 to 2.84 ton/ha in 2021. However, the farm productivity is below the target of 6 ton/ha. The farm productivity in IADA Batang Lupar is also one of the lowest among the granary areas in Malaysia.

To understand why the productivity is relatively low, three sociological scopes were look upon to factor that may influence the productivity are: the structure, process, and culture. The structure refers to the infrastructures and facilities provided by the government. The process refers to the activities carried out by farmers during the production processes. Culture determines the ability of farmers to perform the production process according to the production manual provided by the Department of Agriculture. The dimensions of the variable are as follows:

Structure

Process

Culture

Out of all these dimensions, the study revealed that factors that contributed to the yield gap among farmers in IADA Batang Lupar are as follows:

Structure

Process

Culture

The case study in the IADA Batang Lupar represents the real issues and challenges in paddy production in Malaysia. Human factors are among the main contributors to low production productivity. The government has spent billions of Malaysian Ringgit to transform the paddy industry into a more dynamic, modern, and progressive industry. Besides the infrastructure and technology application, the government must address the sociological factors that could improve the industry.

WAY FORWARD

The focus of the agricultural sector in the 12th Malaysian Economic Development Plan is to increase the productivity and food security. The increase in rice production is closely related to the level of technology use, the efficiency of resource use, and the attitude of farmers. The government has allocated various incentives and subsidies to paddy farmers to support productivity improvement programs as a strategy to increase production throughout the country. Malaysia is worried that the significant dependence on rice supply sources can cause food insecurity and significantly impact the harmony of the people.

The government targeted that by 2030, total rice production will reach 2.32 million tons, with an increase of 53.6% compared to 1.51 million tons in 2019 and a target compounded average growth rate (CAGR) of 4.89%. The total production increase will contribute to the goal set, SSL 80.00%. The average yield of rice paddy per unit of paddy field area will be increased to 5.3 ton/ha compared to the current average yield of 3.5 ton/ha (2019), with a CAGR of 3.84%, to achieve this target.

In the next ten years, the productivity of the paddy and rice sub-sector will be boosted through better efficiency in using natural resources and improving the income levels of industry drivers across the value chain of this sub-sector, especially for the paddy fields. In addition, through a more conducive business environment, the competitiveness and capabilities of this sub-sector will be improved. This aspiration has been translated into five strategies to be implemented in the next ten years. These strategies consider the issues and challenges the paddy and rice sub-sector faces. The five strategies identified are:

The government also aspires to transform Sabah and Sarawak into new sources of rice production. More land areas will be opened and transformed into rice granary areas. The government plans to develop more than 50,000 ha of land in Sabah and Sarawak as Malaysia's new source of paddy production. In a short-term plan, the government is developing 4,839 ha of land in Sabah and Sarawak for paddy cultivation, which is 2,159 ha of land in Sabah, namely in Beluran and Kota Belud, and 2,680 ha in Batang Lupar in Sarawak.

The government will provide funds for improving infrastructure, including irrigation systems, farm roads, paddy mills, etc. To support paddy cultivation in the country, the government allocated RM1.57 (US$0.39) billion in the 2021 Budget to support the industry, including the legal paddy seed incentive, federal government paddy fertilizer scheme, paddy production incentive scheme, fertilizer scheme, pesticides for hill paddy and paddy price subsidy scheme. At the same time, the application of modern farm mechanization technologies will be intensified.

Quite recently, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MAFS) plans to boost the national rice production's Self-Sufficient Levels (SSL) to 80% within the 12th Malaysia Plan period. The ministry has launched a new rice cultivation approach called the Large-Scale Smart Paddy Cultivation (SMART SBB) initiative to achieve this target. The initiative unites paddy fields through contractual or rental agriculture via a management system that optimizes available resources for increased farming effectiveness and post-harvest production. The program aims to raise the average yield per hectare from the average current production of 3.5 ton/ha in 2019 to 7.0 ton/ha under the 12th Malaysian Plan. Technology like the Internet of Things (IoT) and economies of scale will uplift production per hectare. The new initiative has the potential to change the industry landscape to guarantee a secure and consistent national food supply.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture, Malaysia (2022). Booklet Statistics Tanaman (Sub-sektor Tanaman Makanan). Jabatan Pertanian Semenanjung Malaysia, Putrajaya.

Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industri (2020). Dasar Agromakanan Negara 2021-2030 (DAN 2.0):Pemodenan Agromakanan: Menjamin Masa Depan Sekuriti Makanan Negara

Zainol Abidin, A.Z, Sukimi, M.F, Engku Ariff, E. El, Ahmad Sobri A., Abdul Wahab, M.A.M and Suratman, N.H. (2020). Kajian Sosiologi pesawah padi inbred di kawasan IADA Batang Lupar, Sarawak dan IADA Kota Belud, Sabah. Laporan Kajian Sosioekonomi 2020. MARDI, Persiaran MARDI-UPM, 43400 Serdang.