ABSTARCT

The objective of the paper is to examine the major reforms implemented in agricultural marketing to regulate marketing of farm produce in the country; and the extent these reforms helped in achieving market -linked price realization for the farm produce by providing competitive price discovery platform. Furthermore, the market density, market arrivals, infrastructural facilities and use pattern and e-trading performance were analyzed in order to assess the performance of regulated markets and draw future policy directions for performing and non-performing states using the Agricultural Marketing and Farmers Friendly Reform Indices. Data were sourced from previous studies, websites and a research study conducted by the authors. Number of villages and area served by each regulated market is found low and varies across the states. Establishment of new markets to increase the market density is critical, however, e-commodity arrivals in the majority of regulated markets continue to be poor except in few states not only due to inaccessibility but also due to poor infrastructure facilities. Revamping the low/ non arrivals regulated markets is vital for better performance. Feasibility of expansion of Primary Producing Centre (PPC) facilities with focus crops in some of regulated markets can be explored under cluster approach depending upon the capacity utilization of the existing facilities. Though there is an upward trend in the growth of Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs), but the numbers of FPCs are insufficient for the 120 million farmers in India. FPCs seem to falter in terms of risk mitigation, as all the members of FPCs view sudden collapse in market price as their biggest fear. One of the biggest challenges for FPCs is its ineptness in accessing capital. In order to improve the functioning of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) as Market Integrated Partners for successful functioning of PPC, providing handholding services like credit is critical. Lack of quick assaying facilities and non-participation of distant traders resulting no significant increase in competition in e-trading. This emphasizes the need for increasing the participation of the stakeholders like FPOs, farmers groups and the private sector. In many of the markets with e-trading facilities, only few of notified commodities were e-traded. Attracting arrival of a greater number of notified commodities is vital so that by higher level participation of traders, FPOs and unified license holders, additional fee can be collected for the use of e-trading facilities. Upgrading of facilities like cold storage with solar power, construction of market shops, drying yard and rural godowns, installation of solar dryer are vital in the selection of regulated markets by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs) based on the requirements and availability to attract more commodity arrivals and revenue generation. We also observed that the states with high level of reform score are better performers in terms of attracting investments on various segments of supply chain, suggesting that complete implementation of APMC reforms would, no doubt, fetch expected outcome.

Key Words: Agricultural Marketing and Farmers Friendly Reform Indices (AMFFRI), market density, electronic National Agricultural Marketing (eNAM), unified license holders, Primary Processing Centers (PPCs)

INTRODUCTION

For Indian farmers, getting access to the markets at right time then selling their produce at remunerative price continues to be an unresolving issue even today. India’s dominant small famers, accounting for 85% of the total landholdings and hold close to 40% share in the total marketable surpluses (www.downtoearh.org.in), have been suffering much due to lack of remunerative prices for their produce even after implementation of various marketing reforms since independence in order to minimize the marketing costs and margins. The average share of farmers in the consumers' rupee is abysmally low due to high margin and costs and it is found to be in a range of 28% and 78% for various agricultural commodities (Bhoi, et.al. 2019). This is mainly because of uneconomical size of marketable surplus of majority of the farmers as a result of aggregation of their farm produce to move to the nearest market. It is considered a great task due to low and variation in the market density. Though the market density and infrastructure facilities improved over time, inaccessibility and either low or poor utilization of infrastructure facilities of Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMC) continue to be the major concerns resulting in poor market arrivals. Under this background, this policy paper focuses on the status of major agricultural marketing reforms that have been introduced over the period, the extent of adoption of those reforms and existing gaps in attracting commodity arrivals. The paper also suggests future policy directions for improving the performance of APMCs in the country.

FOCUS AND DATA SOURCES

Main objective of the paper is to examine the major reforms implemented in agricultural marketing to regulate marketing of farm produce in the country over the period; and to what extent these reforms helped in achieving the objective of market-linked price realization of the farm produce by providing competitive price discovery platform. The gaps in terms of adoption of market reforms by various states in India and the consequent output in terms of market arrivals and unitization of infrastructural facilities are also analyzed. Finally, the future policy directions are drawn for strategic implementation. Data were sourced from previous studies, websites and a research study conducted by the authors (Selvaraj, et.al. 2021).

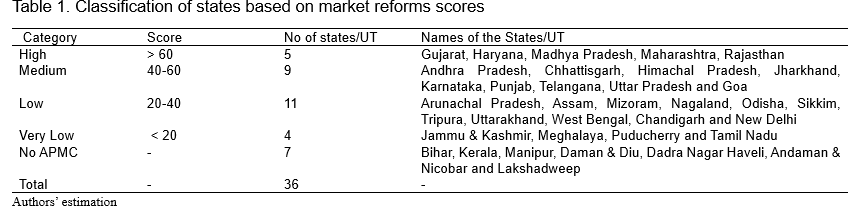

Agricultural Marketing and Farmer Friendly Reforms Indices (AMFFRI) were constructed taking into consideration various factors to compare the status of reforms in agriculture sector across states and Union Territories (UTs) (Chand and Singh, 2016). The indices were developed for each state since adoption of reforms across the states varied significantly and one third of the states and UTs did not adopt any of the APMC reforms and half of the states did not notify the changes in the act. Based on the index we have classified the states into high, medium, low, very low and no APMC states (Table 1) and further analyses were carried out to assess the market density, market arrivals, infrastructure facilities and use pattern and e-trading performance in order to assess the performance of regulated markets and draw future policy directions.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE MARKETING REFORMS IN INDIA

Market regulation in India started as early 1886 with the establishment of Karanjia Cotton Market under the Hyderabad Residency order. Subsequently the Berar Cotton and Grain Market Act was passed in 1897. Prior to independence the Royal Commission on Agriculture (1928) was constituted to suggest regulations in agriculture and marketing keeping in view the importance of agriculture in Indian economy. Thereafter, the Central Banking Enquiry Committee (1931) was constituted in 1931 and the Directorate of Marketing and Inspection was established in 1935 to bring the regulatory mechanisms in agricultural marketing (www.agricoop.nic.in).

The first APMC Act was enacted in 1963 by various states and under this act, agricultural markets in most parts of the country were established and regulated by the Market Committees which was constituted by each State Governments. The whole geographical area of the state was declared as market area restricting the wholesale marketing activities as no person or agency was allowed freely to undertake marketing agricultural commodities in the market area. A monopoly nature of regulation prevented the farmers to adopt innovative marketing system and technologies resulted in noncompetitive marketing system (www.agricoop.nic.in).

Trade openness necessitated to integrate farm production with national and international markets. Recognizing the importance of liberalized agriculture markets, Agricultural Produce Marketing (Development and Regulation) Act, 2003 was enacted to promote new and competitive agricultural market. Amendments were brought in for establishment of private markets/ yards, direct purchase centers, consumer/farmers markets for direct sale and promotion of public private partnership in the management and development of agricultural markets. Provisions were also made for the establishment of special markets for perishable commodities like onions, fruits, vegetables, flowers etc. The role of APMCs and State Agricultural Marketing Boards were redefined. The amendments in the act facilitate pledge financing, e-trading, direct purchasing, export, forward/future trading and introduction of negotiable warehousing receipt system for agricultural commodities (www.agricoop.nic.in).

Since many of states have not adopted the model act’s provisions, a new Model Act was enacted in 2017. The main features of the act are abolition of fragmentation of market within the State/ UT by removing the concept of notified market area, disintermediation of food supply chain by integration of farmers with processors, exporters, bulk retailers and consumers. Creation of a conducive environment for setting up and operating private wholesale market yards and farmer consumer market yards, enabling declaration of warehouses/ silos/ cold storages and other structures/ space as market sub–yard to provide better market access/ linkages to the farmers. Promotion of e-trading, provisions for single point levy of market fee across the state and unified single trading license including rationalization of market fee and commission charges (www.agricoop.nic.in).

With the main aim of facilitating barrier free inter and intra state trade across the country, GoI enacted three laws namely (i) Farmer's Produce, Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020; (ii) Farmers' (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services, 2020; and (iii) Essentials Commodities Amendment Act, 2020. These laws envisage that opening up of agricultural marketing outside the market mandis will create alternate marketing channels there by reducing marketing/ transportation cost and help the farmers in getting better prices. Further, the provisions under these laws provide the facilitative framework for electronic trading and promote barrier free inter-state, intra-state trade of farm produce. The farmers can enter into contract with agri-business firms, processors, wholesalers, exporters or large retailers for the sale of produce at pre-agreed price in order to transfer the risk of unpredictability from farmers to sponsors. Farmers can engage in direct marketing and that there is a third-party quality certification for monitoring and certifying the quality, grade and standards of farm produce and notification of registration authorities by the state government to provide electronic registration of the pre-agreed contracts.

Concerns are that each state will lose revenue since market fee cannot be collected for the produce if traded outside the notified area for the notified crops. If the entire farm trade moves out of the mandis due to this provision in the law, then this will eventually end up the Minimum Support Price (MSP) based procurement system. Furthermore, the facilities created under electronic National Agricultural Marketing (e-NAM) may be underutilized /unutilized, if the entire farm trade goes out of mandis. Also, the use of existing electronic facilities and their operations can also be affected as other than an individual can establish, manage and operate electronic trade and transaction platforms. APMC may incur revenue loss and thus throw many challenges for the APMCs. In our study (Selvaraj, et.al. 2021) we found that Cess collection (market fee for notified crops and notified area) is one of the major sources for market infrastructure development fund. Nearly 88 to 99% of revenue generated through market fee collection is from the sale of the produce outside the market yards due to notified area. There is likely the chance that the loss in revenue could be more than 90% if the present rate of market arrivals continues to exist. These acts were repelled due to various reasons and prolong agitation by the farmers due to the above said concerns.

MARKET REFORMS ADOPTION AND MARKET DENSITY

Access to adequate number of markets is critical as it improves the bargaining power of the farmers and such access enables the farmers to participate in the auction system for suitable price discovery. Since the local traders and agents become the aggregators to transit the produce to APMC, there is always of denial of remunerative prices to farmers for their produce if the market is inaccessible. Producers' share is the proportion of the price received by the farmers that are paid by the consumer and it was estimated by various studies for various marketing channels over the time for assessing the supply channel efficiency. The Millennium study conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture in 2004 indicates that the share of producers varies from 56% to 89% for paddy, 77% to 88% for wheat, 72% to 86% for coarse grains and 79% to 86% for pulses, 40% to 85% in oil seeds and 32% to 68% in case of fruits, vegetables and flowers (Acharya, 2004). Farmer’s share in consumer’s rupee over the last five decades have ranged between 30% and 89% across different crops in the country (Chengappa et al. 2012; Negi et.al,2018). The farmer’s share in consumer’s rupee in the case of fruits and vegetables ranged between 32% and – 68%, while for non-perishables (paddy, wheat, coarse grains, pulses, oilseeds) it ranged between 40% and 89% (GoI 2013). Several studies have shown that despite the implementation of various market reforms, price realization by the farmers continue to be lesser and there was not much increase in the share of producer’s share in consumer rupee due to inaccessibility, low market density, low value addition and low adoption of market reforms by the various states.

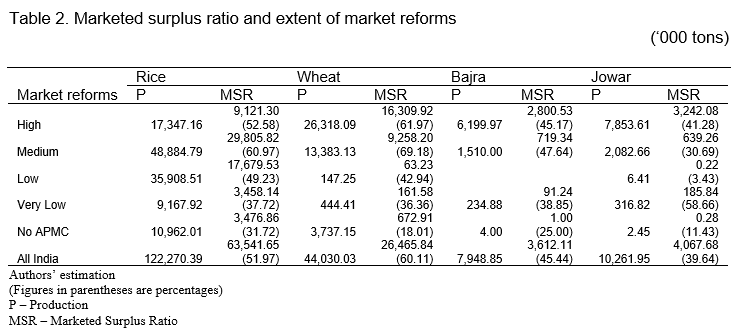

Market interventions through various means can improve the efficiency in the marketing systems and help the farmers to market their produce without any hassle. These interventions are as evident from the implementation of APMC act with various modifications based on the suggestions of the various committees constituted over the time in India. The government has increased market density to provide adequate number of markets to handle ever increasing marketed surplus (Table 2). However, we found that though marketed surplus has been increasing in all the states including low reforms adopted states due to increase in production resulting from technological resilience, the number of villages and area served by each market is low in poorly reforms adopted states. There were 236 regulated markets in India during 1950. There were 6,507 regulated wholesale markets and 20,868 rural primary markets during 2003 and average market density was 116 sq. km and average area served by the regulated market was 435 sq km. The market density varied between 115 and 11,215 sq. km in Punjab and Meghalaya, respectively. Today there are 6,946 (principal and sub-market yards) apart from 22,959 rural periodical markets.

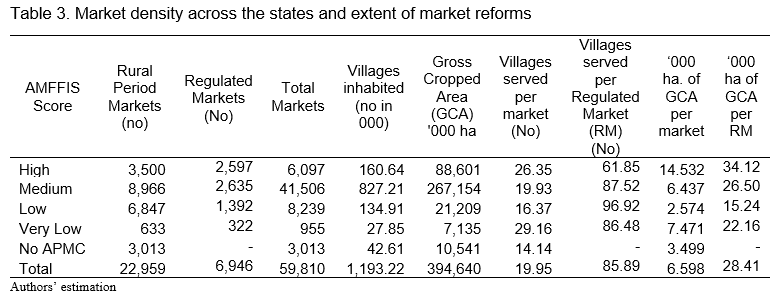

We found that number of villages served by the regulated market in those states with higher reforms (62 villages per market) is comparatively lower (Table 3). On other hand, coverage area is found higher serving 34,120 ha. Among states, there is wide variation in terms of density of markets. In Andhra Pradesh, there was one market for 146 villages, while in Uttar Pradesh there is one market for 17 villages. In Assam, a wholesale market covers about 6,442 sq. km (45 km radius), whereas in Punjab a market covers 116 sq. km of area (6 km radius). However, periodical rural markets are found higher in those states with low and medium score signifying that strict marketing regulatory mechanisms are in place in those states with higher reforms due to amendment of various provisions of the APMC act. It has been reported that market arrivals have increased at a much higher rate than the growth in production, indicating a widening gap between the increase in marketed surplus and the number of markets (Chand, 2012). The National Commission on Farmers suggested a market in a 5 km radius (www.agricoop.nic.in) and the Dalwai Committee has estimated that the country would require 30,000 markets comprising of wholesale and rural retail markets and there is a requirement for 10,130 wholesale markets functioning across the country (www.agricoop.nic.in). The existing numbers of regulated markets are not sufficient enough to cater to the expanding agricultural production of the country.

INFRASTRUCTURE FACILITIES AND ARRIVALS

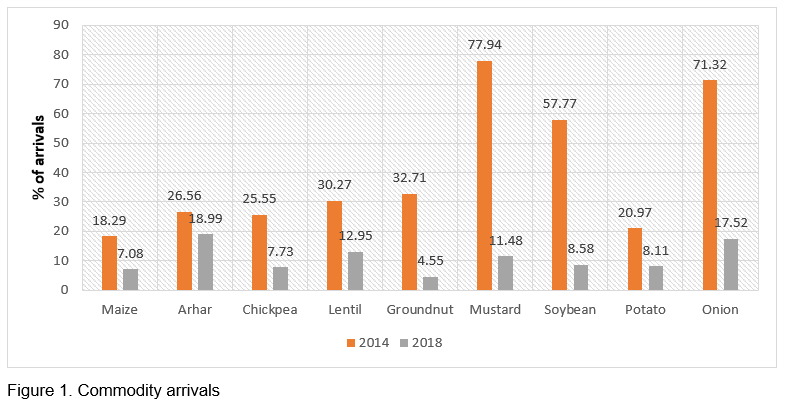

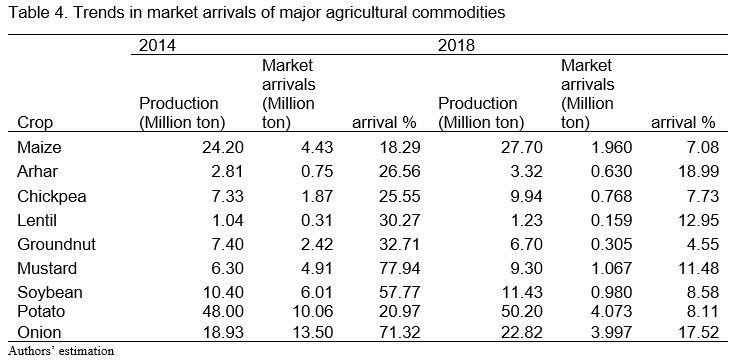

Though regulated markets have established adequate infrastructure facilities, functioning of regulated markets and utilization of existing facilities to its fullest capacity are either low or negligible in many of regulated markets throwing many challenges for effective utilization of available infrastructure facilities and successful functioning of the regulated markets. Arrivals of agricultural produce at regulated markets depends on the facilities/amenities available rather than just the presence of regulated markets per se in the area and transport-connectivity of the market. Furthermore, better market infrastructure helps in curbing marketing losses. The fact was proven by many earlier studies. Both the high rate of investment in providing superior infrastructure facilities and transport connectivity of Rajkot market in Rajasthan attracted consistently high quantity of arrivals (Khunt and Gajipara, 2008). However, there were low market arrivals in four regulated markets in northern Karnataka due to improper weighing of produce and inadequate grading facilities (Vaikunthe, 2000). In Tamil Nadu sales at the market increased significantly with an improvement in market facilities and with decrease in travel time from the village to the market (Shilpi and Umali-Deininger, 2007). Inadequate market infrastructure leads to higher marketing costs and results in low share of producer in consumer’s rupee (Bala, 2009). Improvement in market facilities and increase in market density are facts remain for upward trends in commodity arrivals in the market yards only in few commodities (Table 4) that led us to analyze the availability of infrastructure facilities and utilization pattern.

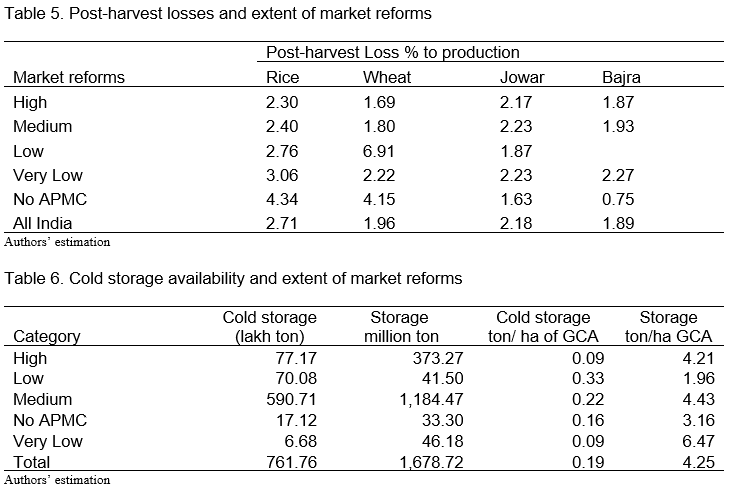

Post-production infrastructure facilities were created for holding inventory for extended durations in the form of rural godowns with ledge loan facilities and cold storages to reduce post-harvest losses thereby ensuring remunerative prices to the farmers. There is still lack of conducive market infrastructure facilities for the sale of agricultural produce and several markets are still found to be poorly equipped to handle the agricultural produce as evident from the market arrivals and post-harvest losses (Tables 5 and 6). It was reported as early as 2004 that there was considerable gap in terms of the facilities created in these yards, even auction platforms were not available in one-third of these markets and common drying facilities were not available in 74% of markets (Acharya 2004). Even after almost two decades many studies have reported that only two-thirds of the regulated markets are equipped with covered and open auction platforms; only one-fourth of the markets have common drying yards (Government of India 2011). It was estimated that post-harvest loss incurred, in per cent of production, in cereals is in the range of 4.65% to 5.99%, in oilseeds and pulses 3.08% to 9.96%, in spices 1.18% to 7.89%, in livestock and fishery produce (milk, meats, fish) 0.92% to 10.52%, and in fruits & vegetables at 4.58% to 15.88% ( Jha, et.a 2015). Our estimates show that after many years of establishment of Agmark Grading Facilities in the country, the grading for export has improved marginally (0.48% of the total quantity of produce graded during 2008 -09 and it was 1.71% during 2017-18).

The proven fact is that there has been dietary diversity that the consumers are moving away from the cereal-centric consumption to more diversified diet including processed food. Increase in per-capita income and changing food habits of the consumers resulted in increase in the domestic demand and export for processed foods for the last couple of decades and further expected to increase many-folds and that led to growth in food-processing industries. Among the numerous initiatives under Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sampada Yojana, Supply Chain Management of Fruits, Vegetables and other Perishables scheme was implemented recently across the states to integrate the farmers with major market centers, processors and consumers and provide the infrastructure facilities for perishable fruits and vegetables in order to reduce post-harvest losses and improve value addition. However, many factors such as fragmented chain, larger number of intermediaries, inadequate infrastructure facilities including cold chain, insufficient mandi system, high cost of packaging, and weak linkages in the supply chain continue to hamper fruit and vegetable supply chains leading to large amount of harvest losses and wastages. Establishment of a greater number of primary and secondary processing units with cluster approach is imperative for value addition of the fruits and vegetables thereby post-harvest losses can be minimized.

Government of India launched a scheme on agro-processing cluster, which aims at development of modern infrastructure and common facilities to encourage group of entrepreneurs to set up food processing units based on cluster approach by linking groups of producers/ farmers to the processors and markets through well-equipped supply chain with modern infrastructure. Each agro processing clusters under the scheme have two basic components i.e. Basic Enabling Infrastructure (roads, water supply, power supply, drainage, ETP etc.), Core Infrastructure/ Common facilities (ware houses, cold storages, IQF, tetra pack, sorting, grading etc.). Every state in the country established Primary Processing Centers in various clusters and these primary processing centers were equipped with state-of-the-art facilities for cleaning, washing, sorting, grading, packing and forward transactions using single/ multiple vegetable and fruit process lines. Further, post-harvest infrastructure facilities such as pack house, cold storage, storage godowns, facilities like Gamma Radiation processing, Individually Quick Freezing (IQF), Vapor heat treatment and pack houses were also created. The established pack houses were also accredited by the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) to meet the standards of the export market. A quality control lab is also provided for the assessment of the quality of produce before and after processing. This is to ensure the high quality standards of the produce delivered from the processing centers. Further, it is expected that there would be 100% price realization with 10% on savings from less process loss, saving of 15% of the cost on market handling charges, 5% direct savings on quality and quantity specific deterioration and overall savings is 20% with 100% price realization for graded produce.

Realizing the importance of FPOs, Farmer Producer Organizations have been selected as Market Integration Partners (MIP) to operate the Primary Processing Centers in order to encourage farmers’ participation. Market Integration Partner is a successful bidder (Farmer Producer Organization or Company registered under any of the following legal provisions, or as Consortium of FPCs or as Federation of FPOs) who has been awarded the contract to operate the particular PPC for 3 years. By utilizing the facilities of PPC by FPOs, it is expected that farmers get better remunerative prices for their produce and by sale of processed produce to retail fruits and vegetable shops including online trading and export, FPOs can earn sizeable profits through margins. However, our experiences with FPOs as MIP in the state of Tamil Nadu is that of all the 25 PPCs, which were handed over to FPOs, many of them are still not effectively functioning.

One of the major reforms is eNAM and the objective of promoting e-trading in the regulated marketing system is to facilitate farmers, traders, buyers, exporters and processors with a common e-platform for trading commodities to ensure remunerative prices for the farmers since this provides access to farmers and traders to national markets. E-markets increase competition among traders across India and provide a national marketplace for free and fair price discovery for agricultural commodities. As on 31 August 2022 eNAM has been integrated with regulated markets in 21states. About 17 million farmers, 0.23 million traders and 0.11 million commission agents have registered with e-NAM. About 43.1 million tons of commodities were e-traded with a value of 1,313.90 million USD [Rs. 107,530 million] as on March 31st 2021 (www.enam.gov.in). The majority of the eNAM integrated markets have godowns or warehouses and very few have modern facilities to handle perishable produce. Scientific assaying, packaging and pre-conditioning of produce, is not readily possible at these centers.

Since many of the facilities created under eNAM are not utilized properly, we conducted a case study to assess the possibility of leasing out the e-trading facilities. Various performance indicators in terms of number of farmers/ traders participated in e-trading since inception, quantity e-traded and value of e-trade and fees collected from traders, initial establishment cost associated with creating facilities such as grading, sorting and assaying were examined and compared with the other regulated markets with e-trading facilities in the state of Tamil Nadu. Consequently, an alternative measure of effectively utilizing the e-trading facilities created is leasing. Therefore, it is critically important to assess the performance of those markets created with -e-trading facilities before the suggestion is made for alternative use e - NAM was implemented. There are three regulated markets presently functioning in the select districts with e-trading facilities in Tamil Nadu State. Cumbam regulated market of Theni district was integrated with common e-platform for e-trading of commodities at the national level during 2017, while Harur regulated market in Dharmapuri district and Theni regulated market in Theni district were subsequently integrated with common e-platform for trading of commodities in 2020.

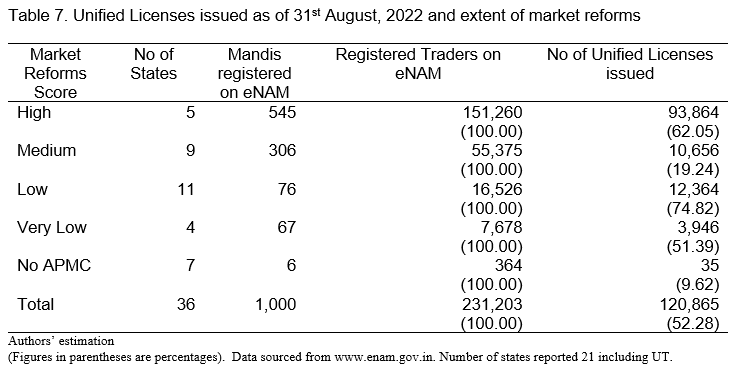

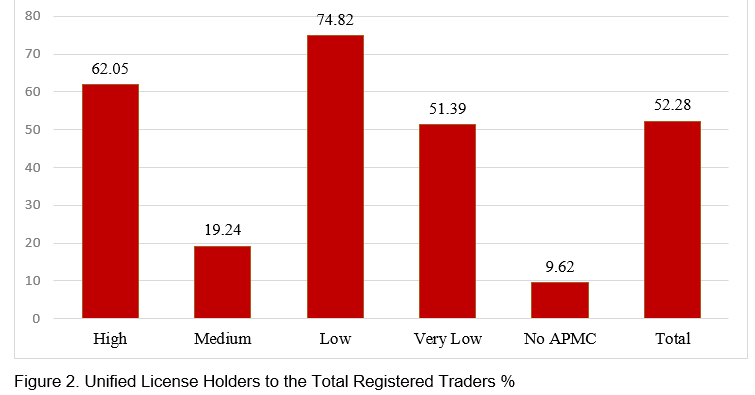

Cumbam regulated market, which was integrated with e-NAM since 2017 has been attracting a large number of farmers to market their produce by e-trading. There were only 50 farmers who participated in e-trading during the inception year and the participation rate increased substantially during the second year with 176 farmers traded their produce through e-NAM platform (www.enam.gov.in). However, farmers' participation declined in the subsequent years and not much improvement in traders' participation and a maximum of only 10-12 traders participated in e-trading per year. The FPOs participation in e-trading in Cumbam regulated market was remarkably low and there is no marked improvement in FPO participation despite the fact that there are 12 FPOs presently functioning in the district itself. We observe that the number is only 50% of the registered traders that have been issued with unified license and varied across the states (Table 7). However, we found that in some states with high reform score have lesser number of unified licenses holders and even none of the registered traders issued with unified license in the case of Maharashtra. In some states with low and medium reforms score, all the registered traders are unified license holders namely Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Telangana and Uttarakhand. In the state of Tamil Nadu, 3,946 unified single licenses have been issued to the traders. We found that there are only 2 unified license holders in the Cumbam regulated market participated in the e-trading (Selvaraj, et.al., 2022)

FUTURE CHALLENGES AND POLICY DIRECTIONS

The country requires higher physical infrastructure facilities including logistics for the effective market linkages to reduce post production losses and benefit the farmers in realizing the remunerative prices. The number of villages and areas served by each regulated market is found low and varies across the states. But the country has to be very cautious in establishing new markets to increase the market density since the commodity arrivals in the majority of regulated markets continue to be poor except for a few states which do not have available infrastructure facilities. Therefore, measures are to be taken to revamp the low/ nonarrivals regulated markets. Feasibility of expansion of PPC facilities with focus crops to some of regulated markets can be explored depending upon the capacity utilization of the existing facilities since the country has already implemented the cluster approach. Though there is an upward trend in the growth of FPCs, but the numbers of FPCs are insufficient for the 120 million farmers in India. FPCs seem to falter in terms of risk mitigation, as all the members of FPCs view sudden collapse in market price as their biggest fear. One of the biggest challenges for FPCs is its ineptness in accessing capital. In order to improve the functioning of FPOs as Market Integrated Partners for successful functioning of PPC, providing handholding services like credit is critical.

The fact remains that e-trading led to increase in prices received by the farmers and timely online payment of sale proceeds to the farmers by reducing the chances of collusion among traders. However, lack of quick assaying facilities and non-participation of distant traders resulting in no significant increase in competition. This emphasizes the need for increasing the participation of the stakeholders like FPOs, farmers groups and private sector. In many of the markets with e-trading facilities, only few of notified commodities were e-traded. Attracting arrival of a greater number of notified commodities is vital so that by higher level participation of traders, FPOs and unified license holders additional fee can be collected for the use of e-trading facilities. Upgrading of facilities like cold storage with solar power, construction of market shops, drying yard and rural godowns, installation of solar dryers are vital in selected APMCs based on the requirements and availability to attract more commodity arrivals and revenue generation. We also observed that the states with high level of reform scores are better performers in terms of attracting investments on various segments of the supply chain suggesting that complete implementation of APMC reforms would, no doubt, fetch expected outcome.

REFERENCES

Acharya, S.S. (2004). State of the Indian farmer, A millennium study on Agricultural Marketing, Department of Agricultural and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, and Academic Foundation, New Delhi.

Bala, B. (2009). Marketing efficiency of cooperative marketing societies in Himachal Pradesh: A case study of vegetables. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing.vol.23: pp: 99-108.

Bhoi B. Binod, Sujata Kundu, Vimal Kishore and D. Suganthi (2019). Supply chain dynamics and food inflation in India. RBI Bulletin. October 2019. pp: 95-111.

Chand, R. (2012). Development policies and agricultural markets. Economic and Political Weekly. Vol.47: pp: 53-63

Chand Ramesh and Jaspal Singh (2016). Study report on agricultural marketing and farmer friendly reforms across Indian States and UTs. National Institution for Transforming India, NITI Aayog, New Delhi, October, 2016.

Chengappa, P.G., A.V., Manjunatha, V. Dimble and K. Shah (2012). Competitive assessment of onion markets in India. Agricultural Development and Rural Transformation Centre Institute for Social and Economic Change, Nagarabhavi, Bangalore.

Down to Earth, Fortnightly Magazine, 17th January, 2018. The Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi, India. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/india-needs-30-000-agri-markets-to-give-fair-deal-to-farmers-59513.

GoI (2013), ‘Final Report of Committee of State Ministers, In-charge of Agriculture Marketing to Promote Reforms’, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture and Co-operation, Government of India, New Delhi.

ICAR-CIPHET. (2015). Assessment of quantitative harvest and post-harvest losses of major crops and commodities in India. ICAR, New Delhi.

Khunt, K., Vekariya, S., and Gajipara, H. (2008). Performance and problems of regulated markets in Gujarat. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, Vol.22(1). pp: 82-98.

National Agricultural Market, Small Farmers Agribuiness Consortium. Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.enam.gov.in

National Commission on Farmers Serving: Farmers and Saving Farming 2006: Year of Agricultural Renewal. Third Report. Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI.

National Paper -PLP-2020-21. Market linkages for Agricultural Commodities. pp: 1-8. National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development, Mumbai www.nabard.org.

Negi, D.S, P.S. Birthal, D. Roy and M.T. Khan (2018), ‘Farmers’ Choice of Market Channels and Producer Prices in India: Role of Transportation and Communication Networks’, Food Policy, Vol. 81, pp. 106-121.

NITI Policy Paper No.1/2017: Doubling of Farmers income Rationale, Strategy Prospects and Action Plan, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.agricoop.nic.in/en/doubling-farmers.

Ranjit Kumar, Sanjiv Kumar, PC Meena, B Ganesh Kumar and N Sivaramane (2021). Strengthening e-NAM in India: way forward. National Academy of Agricultural Research Management, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Reddy A. Amarender (2018). Electronic national agricultural markets: the way forward. Current Science. Vol 115(5). pp: 826 -837.

Report of the Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income (2017). Volume IV “Post-production interventions: Agricultural Marketing” Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers’ Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers. August. 2017.

Selvaraj, K. N, K.R.Ashok and R.Parimalarangan (2021). Feasibility study for improving the performance of regulated markets in Tamil nadu. Research Report/Policy Briefs. Department of Agricultural Marketing and Agribusiness, Government of Tamil Nadu.

Selvaraj, K.N., R.Parimalarangan and Susmitha Burigi (2022). E-trading facilities utilization pattern in regulated markets of Tamil nadu and feasibility of converting low/non-arrival regulated markets into primary processing centres. Agricultural Situation in India. Vol. LXXIX (2). pp:21-33.

Shilpi, F., and Umali-Deininger, D. (2007). Where to sell? market facilities and agricultural marketing. Policy Research Working Paper 4455. The World Bank.

Vaikunthe, L. (2000). Regulatory framework for agricultural marketing-a case study of APMCs in Karnataka. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, Vol.14(3). pp: 1-7.

The draft model legislation titled the State Agricultural Produce Marketing (Development and Regulation) Act, 2003. Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.agricoop.nic.in/default/files/apmc, 2003.

The State/UT Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion & Facilitation) Act, 2017, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.agricoop.nic.in/default/files/ apmc, 2017.

Agricultural Marketing Reforms in India – Future Challenges and Opportunities

ABSTARCT

The objective of the paper is to examine the major reforms implemented in agricultural marketing to regulate marketing of farm produce in the country; and the extent these reforms helped in achieving market -linked price realization for the farm produce by providing competitive price discovery platform. Furthermore, the market density, market arrivals, infrastructural facilities and use pattern and e-trading performance were analyzed in order to assess the performance of regulated markets and draw future policy directions for performing and non-performing states using the Agricultural Marketing and Farmers Friendly Reform Indices. Data were sourced from previous studies, websites and a research study conducted by the authors. Number of villages and area served by each regulated market is found low and varies across the states. Establishment of new markets to increase the market density is critical, however, e-commodity arrivals in the majority of regulated markets continue to be poor except in few states not only due to inaccessibility but also due to poor infrastructure facilities. Revamping the low/ non arrivals regulated markets is vital for better performance. Feasibility of expansion of Primary Producing Centre (PPC) facilities with focus crops in some of regulated markets can be explored under cluster approach depending upon the capacity utilization of the existing facilities. Though there is an upward trend in the growth of Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs), but the numbers of FPCs are insufficient for the 120 million farmers in India. FPCs seem to falter in terms of risk mitigation, as all the members of FPCs view sudden collapse in market price as their biggest fear. One of the biggest challenges for FPCs is its ineptness in accessing capital. In order to improve the functioning of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) as Market Integrated Partners for successful functioning of PPC, providing handholding services like credit is critical. Lack of quick assaying facilities and non-participation of distant traders resulting no significant increase in competition in e-trading. This emphasizes the need for increasing the participation of the stakeholders like FPOs, farmers groups and the private sector. In many of the markets with e-trading facilities, only few of notified commodities were e-traded. Attracting arrival of a greater number of notified commodities is vital so that by higher level participation of traders, FPOs and unified license holders, additional fee can be collected for the use of e-trading facilities. Upgrading of facilities like cold storage with solar power, construction of market shops, drying yard and rural godowns, installation of solar dryer are vital in the selection of regulated markets by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs) based on the requirements and availability to attract more commodity arrivals and revenue generation. We also observed that the states with high level of reform score are better performers in terms of attracting investments on various segments of supply chain, suggesting that complete implementation of APMC reforms would, no doubt, fetch expected outcome.

Key Words: Agricultural Marketing and Farmers Friendly Reform Indices (AMFFRI), market density, electronic National Agricultural Marketing (eNAM), unified license holders, Primary Processing Centers (PPCs)

INTRODUCTION

For Indian farmers, getting access to the markets at right time then selling their produce at remunerative price continues to be an unresolving issue even today. India’s dominant small famers, accounting for 85% of the total landholdings and hold close to 40% share in the total marketable surpluses (www.downtoearh.org.in), have been suffering much due to lack of remunerative prices for their produce even after implementation of various marketing reforms since independence in order to minimize the marketing costs and margins. The average share of farmers in the consumers' rupee is abysmally low due to high margin and costs and it is found to be in a range of 28% and 78% for various agricultural commodities (Bhoi, et.al. 2019). This is mainly because of uneconomical size of marketable surplus of majority of the farmers as a result of aggregation of their farm produce to move to the nearest market. It is considered a great task due to low and variation in the market density. Though the market density and infrastructure facilities improved over time, inaccessibility and either low or poor utilization of infrastructure facilities of Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMC) continue to be the major concerns resulting in poor market arrivals. Under this background, this policy paper focuses on the status of major agricultural marketing reforms that have been introduced over the period, the extent of adoption of those reforms and existing gaps in attracting commodity arrivals. The paper also suggests future policy directions for improving the performance of APMCs in the country.

FOCUS AND DATA SOURCES

Main objective of the paper is to examine the major reforms implemented in agricultural marketing to regulate marketing of farm produce in the country over the period; and to what extent these reforms helped in achieving the objective of market-linked price realization of the farm produce by providing competitive price discovery platform. The gaps in terms of adoption of market reforms by various states in India and the consequent output in terms of market arrivals and unitization of infrastructural facilities are also analyzed. Finally, the future policy directions are drawn for strategic implementation. Data were sourced from previous studies, websites and a research study conducted by the authors (Selvaraj, et.al. 2021).

Agricultural Marketing and Farmer Friendly Reforms Indices (AMFFRI) were constructed taking into consideration various factors to compare the status of reforms in agriculture sector across states and Union Territories (UTs) (Chand and Singh, 2016). The indices were developed for each state since adoption of reforms across the states varied significantly and one third of the states and UTs did not adopt any of the APMC reforms and half of the states did not notify the changes in the act. Based on the index we have classified the states into high, medium, low, very low and no APMC states (Table 1) and further analyses were carried out to assess the market density, market arrivals, infrastructure facilities and use pattern and e-trading performance in order to assess the performance of regulated markets and draw future policy directions.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE MARKETING REFORMS IN INDIA

Market regulation in India started as early 1886 with the establishment of Karanjia Cotton Market under the Hyderabad Residency order. Subsequently the Berar Cotton and Grain Market Act was passed in 1897. Prior to independence the Royal Commission on Agriculture (1928) was constituted to suggest regulations in agriculture and marketing keeping in view the importance of agriculture in Indian economy. Thereafter, the Central Banking Enquiry Committee (1931) was constituted in 1931 and the Directorate of Marketing and Inspection was established in 1935 to bring the regulatory mechanisms in agricultural marketing (www.agricoop.nic.in).

The first APMC Act was enacted in 1963 by various states and under this act, agricultural markets in most parts of the country were established and regulated by the Market Committees which was constituted by each State Governments. The whole geographical area of the state was declared as market area restricting the wholesale marketing activities as no person or agency was allowed freely to undertake marketing agricultural commodities in the market area. A monopoly nature of regulation prevented the farmers to adopt innovative marketing system and technologies resulted in noncompetitive marketing system (www.agricoop.nic.in).

Trade openness necessitated to integrate farm production with national and international markets. Recognizing the importance of liberalized agriculture markets, Agricultural Produce Marketing (Development and Regulation) Act, 2003 was enacted to promote new and competitive agricultural market. Amendments were brought in for establishment of private markets/ yards, direct purchase centers, consumer/farmers markets for direct sale and promotion of public private partnership in the management and development of agricultural markets. Provisions were also made for the establishment of special markets for perishable commodities like onions, fruits, vegetables, flowers etc. The role of APMCs and State Agricultural Marketing Boards were redefined. The amendments in the act facilitate pledge financing, e-trading, direct purchasing, export, forward/future trading and introduction of negotiable warehousing receipt system for agricultural commodities (www.agricoop.nic.in).

Since many of states have not adopted the model act’s provisions, a new Model Act was enacted in 2017. The main features of the act are abolition of fragmentation of market within the State/ UT by removing the concept of notified market area, disintermediation of food supply chain by integration of farmers with processors, exporters, bulk retailers and consumers. Creation of a conducive environment for setting up and operating private wholesale market yards and farmer consumer market yards, enabling declaration of warehouses/ silos/ cold storages and other structures/ space as market sub–yard to provide better market access/ linkages to the farmers. Promotion of e-trading, provisions for single point levy of market fee across the state and unified single trading license including rationalization of market fee and commission charges (www.agricoop.nic.in).

With the main aim of facilitating barrier free inter and intra state trade across the country, GoI enacted three laws namely (i) Farmer's Produce, Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020; (ii) Farmers' (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services, 2020; and (iii) Essentials Commodities Amendment Act, 2020. These laws envisage that opening up of agricultural marketing outside the market mandis will create alternate marketing channels there by reducing marketing/ transportation cost and help the farmers in getting better prices. Further, the provisions under these laws provide the facilitative framework for electronic trading and promote barrier free inter-state, intra-state trade of farm produce. The farmers can enter into contract with agri-business firms, processors, wholesalers, exporters or large retailers for the sale of produce at pre-agreed price in order to transfer the risk of unpredictability from farmers to sponsors. Farmers can engage in direct marketing and that there is a third-party quality certification for monitoring and certifying the quality, grade and standards of farm produce and notification of registration authorities by the state government to provide electronic registration of the pre-agreed contracts.

Concerns are that each state will lose revenue since market fee cannot be collected for the produce if traded outside the notified area for the notified crops. If the entire farm trade moves out of the mandis due to this provision in the law, then this will eventually end up the Minimum Support Price (MSP) based procurement system. Furthermore, the facilities created under electronic National Agricultural Marketing (e-NAM) may be underutilized /unutilized, if the entire farm trade goes out of mandis. Also, the use of existing electronic facilities and their operations can also be affected as other than an individual can establish, manage and operate electronic trade and transaction platforms. APMC may incur revenue loss and thus throw many challenges for the APMCs. In our study (Selvaraj, et.al. 2021) we found that Cess collection (market fee for notified crops and notified area) is one of the major sources for market infrastructure development fund. Nearly 88 to 99% of revenue generated through market fee collection is from the sale of the produce outside the market yards due to notified area. There is likely the chance that the loss in revenue could be more than 90% if the present rate of market arrivals continues to exist. These acts were repelled due to various reasons and prolong agitation by the farmers due to the above said concerns.

MARKET REFORMS ADOPTION AND MARKET DENSITY

Access to adequate number of markets is critical as it improves the bargaining power of the farmers and such access enables the farmers to participate in the auction system for suitable price discovery. Since the local traders and agents become the aggregators to transit the produce to APMC, there is always of denial of remunerative prices to farmers for their produce if the market is inaccessible. Producers' share is the proportion of the price received by the farmers that are paid by the consumer and it was estimated by various studies for various marketing channels over the time for assessing the supply channel efficiency. The Millennium study conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture in 2004 indicates that the share of producers varies from 56% to 89% for paddy, 77% to 88% for wheat, 72% to 86% for coarse grains and 79% to 86% for pulses, 40% to 85% in oil seeds and 32% to 68% in case of fruits, vegetables and flowers (Acharya, 2004). Farmer’s share in consumer’s rupee over the last five decades have ranged between 30% and 89% across different crops in the country (Chengappa et al. 2012; Negi et.al,2018). The farmer’s share in consumer’s rupee in the case of fruits and vegetables ranged between 32% and – 68%, while for non-perishables (paddy, wheat, coarse grains, pulses, oilseeds) it ranged between 40% and 89% (GoI 2013). Several studies have shown that despite the implementation of various market reforms, price realization by the farmers continue to be lesser and there was not much increase in the share of producer’s share in consumer rupee due to inaccessibility, low market density, low value addition and low adoption of market reforms by the various states.

Market interventions through various means can improve the efficiency in the marketing systems and help the farmers to market their produce without any hassle. These interventions are as evident from the implementation of APMC act with various modifications based on the suggestions of the various committees constituted over the time in India. The government has increased market density to provide adequate number of markets to handle ever increasing marketed surplus (Table 2). However, we found that though marketed surplus has been increasing in all the states including low reforms adopted states due to increase in production resulting from technological resilience, the number of villages and area served by each market is low in poorly reforms adopted states. There were 236 regulated markets in India during 1950. There were 6,507 regulated wholesale markets and 20,868 rural primary markets during 2003 and average market density was 116 sq. km and average area served by the regulated market was 435 sq km. The market density varied between 115 and 11,215 sq. km in Punjab and Meghalaya, respectively. Today there are 6,946 (principal and sub-market yards) apart from 22,959 rural periodical markets.

We found that number of villages served by the regulated market in those states with higher reforms (62 villages per market) is comparatively lower (Table 3). On other hand, coverage area is found higher serving 34,120 ha. Among states, there is wide variation in terms of density of markets. In Andhra Pradesh, there was one market for 146 villages, while in Uttar Pradesh there is one market for 17 villages. In Assam, a wholesale market covers about 6,442 sq. km (45 km radius), whereas in Punjab a market covers 116 sq. km of area (6 km radius). However, periodical rural markets are found higher in those states with low and medium score signifying that strict marketing regulatory mechanisms are in place in those states with higher reforms due to amendment of various provisions of the APMC act. It has been reported that market arrivals have increased at a much higher rate than the growth in production, indicating a widening gap between the increase in marketed surplus and the number of markets (Chand, 2012). The National Commission on Farmers suggested a market in a 5 km radius (www.agricoop.nic.in) and the Dalwai Committee has estimated that the country would require 30,000 markets comprising of wholesale and rural retail markets and there is a requirement for 10,130 wholesale markets functioning across the country (www.agricoop.nic.in). The existing numbers of regulated markets are not sufficient enough to cater to the expanding agricultural production of the country.

INFRASTRUCTURE FACILITIES AND ARRIVALS

Though regulated markets have established adequate infrastructure facilities, functioning of regulated markets and utilization of existing facilities to its fullest capacity are either low or negligible in many of regulated markets throwing many challenges for effective utilization of available infrastructure facilities and successful functioning of the regulated markets. Arrivals of agricultural produce at regulated markets depends on the facilities/amenities available rather than just the presence of regulated markets per se in the area and transport-connectivity of the market. Furthermore, better market infrastructure helps in curbing marketing losses. The fact was proven by many earlier studies. Both the high rate of investment in providing superior infrastructure facilities and transport connectivity of Rajkot market in Rajasthan attracted consistently high quantity of arrivals (Khunt and Gajipara, 2008). However, there were low market arrivals in four regulated markets in northern Karnataka due to improper weighing of produce and inadequate grading facilities (Vaikunthe, 2000). In Tamil Nadu sales at the market increased significantly with an improvement in market facilities and with decrease in travel time from the village to the market (Shilpi and Umali-Deininger, 2007). Inadequate market infrastructure leads to higher marketing costs and results in low share of producer in consumer’s rupee (Bala, 2009). Improvement in market facilities and increase in market density are facts remain for upward trends in commodity arrivals in the market yards only in few commodities (Table 4) that led us to analyze the availability of infrastructure facilities and utilization pattern.

Post-production infrastructure facilities were created for holding inventory for extended durations in the form of rural godowns with ledge loan facilities and cold storages to reduce post-harvest losses thereby ensuring remunerative prices to the farmers. There is still lack of conducive market infrastructure facilities for the sale of agricultural produce and several markets are still found to be poorly equipped to handle the agricultural produce as evident from the market arrivals and post-harvest losses (Tables 5 and 6). It was reported as early as 2004 that there was considerable gap in terms of the facilities created in these yards, even auction platforms were not available in one-third of these markets and common drying facilities were not available in 74% of markets (Acharya 2004). Even after almost two decades many studies have reported that only two-thirds of the regulated markets are equipped with covered and open auction platforms; only one-fourth of the markets have common drying yards (Government of India 2011). It was estimated that post-harvest loss incurred, in per cent of production, in cereals is in the range of 4.65% to 5.99%, in oilseeds and pulses 3.08% to 9.96%, in spices 1.18% to 7.89%, in livestock and fishery produce (milk, meats, fish) 0.92% to 10.52%, and in fruits & vegetables at 4.58% to 15.88% ( Jha, et.a 2015). Our estimates show that after many years of establishment of Agmark Grading Facilities in the country, the grading for export has improved marginally (0.48% of the total quantity of produce graded during 2008 -09 and it was 1.71% during 2017-18).

The proven fact is that there has been dietary diversity that the consumers are moving away from the cereal-centric consumption to more diversified diet including processed food. Increase in per-capita income and changing food habits of the consumers resulted in increase in the domestic demand and export for processed foods for the last couple of decades and further expected to increase many-folds and that led to growth in food-processing industries. Among the numerous initiatives under Pradhan Mantri Kisan Sampada Yojana, Supply Chain Management of Fruits, Vegetables and other Perishables scheme was implemented recently across the states to integrate the farmers with major market centers, processors and consumers and provide the infrastructure facilities for perishable fruits and vegetables in order to reduce post-harvest losses and improve value addition. However, many factors such as fragmented chain, larger number of intermediaries, inadequate infrastructure facilities including cold chain, insufficient mandi system, high cost of packaging, and weak linkages in the supply chain continue to hamper fruit and vegetable supply chains leading to large amount of harvest losses and wastages. Establishment of a greater number of primary and secondary processing units with cluster approach is imperative for value addition of the fruits and vegetables thereby post-harvest losses can be minimized.

Government of India launched a scheme on agro-processing cluster, which aims at development of modern infrastructure and common facilities to encourage group of entrepreneurs to set up food processing units based on cluster approach by linking groups of producers/ farmers to the processors and markets through well-equipped supply chain with modern infrastructure. Each agro processing clusters under the scheme have two basic components i.e. Basic Enabling Infrastructure (roads, water supply, power supply, drainage, ETP etc.), Core Infrastructure/ Common facilities (ware houses, cold storages, IQF, tetra pack, sorting, grading etc.). Every state in the country established Primary Processing Centers in various clusters and these primary processing centers were equipped with state-of-the-art facilities for cleaning, washing, sorting, grading, packing and forward transactions using single/ multiple vegetable and fruit process lines. Further, post-harvest infrastructure facilities such as pack house, cold storage, storage godowns, facilities like Gamma Radiation processing, Individually Quick Freezing (IQF), Vapor heat treatment and pack houses were also created. The established pack houses were also accredited by the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) to meet the standards of the export market. A quality control lab is also provided for the assessment of the quality of produce before and after processing. This is to ensure the high quality standards of the produce delivered from the processing centers. Further, it is expected that there would be 100% price realization with 10% on savings from less process loss, saving of 15% of the cost on market handling charges, 5% direct savings on quality and quantity specific deterioration and overall savings is 20% with 100% price realization for graded produce.

Realizing the importance of FPOs, Farmer Producer Organizations have been selected as Market Integration Partners (MIP) to operate the Primary Processing Centers in order to encourage farmers’ participation. Market Integration Partner is a successful bidder (Farmer Producer Organization or Company registered under any of the following legal provisions, or as Consortium of FPCs or as Federation of FPOs) who has been awarded the contract to operate the particular PPC for 3 years. By utilizing the facilities of PPC by FPOs, it is expected that farmers get better remunerative prices for their produce and by sale of processed produce to retail fruits and vegetable shops including online trading and export, FPOs can earn sizeable profits through margins. However, our experiences with FPOs as MIP in the state of Tamil Nadu is that of all the 25 PPCs, which were handed over to FPOs, many of them are still not effectively functioning.

One of the major reforms is eNAM and the objective of promoting e-trading in the regulated marketing system is to facilitate farmers, traders, buyers, exporters and processors with a common e-platform for trading commodities to ensure remunerative prices for the farmers since this provides access to farmers and traders to national markets. E-markets increase competition among traders across India and provide a national marketplace for free and fair price discovery for agricultural commodities. As on 31 August 2022 eNAM has been integrated with regulated markets in 21states. About 17 million farmers, 0.23 million traders and 0.11 million commission agents have registered with e-NAM. About 43.1 million tons of commodities were e-traded with a value of 1,313.90 million USD [Rs. 107,530 million] as on March 31st 2021 (www.enam.gov.in). The majority of the eNAM integrated markets have godowns or warehouses and very few have modern facilities to handle perishable produce. Scientific assaying, packaging and pre-conditioning of produce, is not readily possible at these centers.

Since many of the facilities created under eNAM are not utilized properly, we conducted a case study to assess the possibility of leasing out the e-trading facilities. Various performance indicators in terms of number of farmers/ traders participated in e-trading since inception, quantity e-traded and value of e-trade and fees collected from traders, initial establishment cost associated with creating facilities such as grading, sorting and assaying were examined and compared with the other regulated markets with e-trading facilities in the state of Tamil Nadu. Consequently, an alternative measure of effectively utilizing the e-trading facilities created is leasing. Therefore, it is critically important to assess the performance of those markets created with -e-trading facilities before the suggestion is made for alternative use e - NAM was implemented. There are three regulated markets presently functioning in the select districts with e-trading facilities in Tamil Nadu State. Cumbam regulated market of Theni district was integrated with common e-platform for e-trading of commodities at the national level during 2017, while Harur regulated market in Dharmapuri district and Theni regulated market in Theni district were subsequently integrated with common e-platform for trading of commodities in 2020.

Cumbam regulated market, which was integrated with e-NAM since 2017 has been attracting a large number of farmers to market their produce by e-trading. There were only 50 farmers who participated in e-trading during the inception year and the participation rate increased substantially during the second year with 176 farmers traded their produce through e-NAM platform (www.enam.gov.in). However, farmers' participation declined in the subsequent years and not much improvement in traders' participation and a maximum of only 10-12 traders participated in e-trading per year. The FPOs participation in e-trading in Cumbam regulated market was remarkably low and there is no marked improvement in FPO participation despite the fact that there are 12 FPOs presently functioning in the district itself. We observe that the number is only 50% of the registered traders that have been issued with unified license and varied across the states (Table 7). However, we found that in some states with high reform score have lesser number of unified licenses holders and even none of the registered traders issued with unified license in the case of Maharashtra. In some states with low and medium reforms score, all the registered traders are unified license holders namely Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Telangana and Uttarakhand. In the state of Tamil Nadu, 3,946 unified single licenses have been issued to the traders. We found that there are only 2 unified license holders in the Cumbam regulated market participated in the e-trading (Selvaraj, et.al., 2022)

FUTURE CHALLENGES AND POLICY DIRECTIONS

The country requires higher physical infrastructure facilities including logistics for the effective market linkages to reduce post production losses and benefit the farmers in realizing the remunerative prices. The number of villages and areas served by each regulated market is found low and varies across the states. But the country has to be very cautious in establishing new markets to increase the market density since the commodity arrivals in the majority of regulated markets continue to be poor except for a few states which do not have available infrastructure facilities. Therefore, measures are to be taken to revamp the low/ nonarrivals regulated markets. Feasibility of expansion of PPC facilities with focus crops to some of regulated markets can be explored depending upon the capacity utilization of the existing facilities since the country has already implemented the cluster approach. Though there is an upward trend in the growth of FPCs, but the numbers of FPCs are insufficient for the 120 million farmers in India. FPCs seem to falter in terms of risk mitigation, as all the members of FPCs view sudden collapse in market price as their biggest fear. One of the biggest challenges for FPCs is its ineptness in accessing capital. In order to improve the functioning of FPOs as Market Integrated Partners for successful functioning of PPC, providing handholding services like credit is critical.

The fact remains that e-trading led to increase in prices received by the farmers and timely online payment of sale proceeds to the farmers by reducing the chances of collusion among traders. However, lack of quick assaying facilities and non-participation of distant traders resulting in no significant increase in competition. This emphasizes the need for increasing the participation of the stakeholders like FPOs, farmers groups and private sector. In many of the markets with e-trading facilities, only few of notified commodities were e-traded. Attracting arrival of a greater number of notified commodities is vital so that by higher level participation of traders, FPOs and unified license holders additional fee can be collected for the use of e-trading facilities. Upgrading of facilities like cold storage with solar power, construction of market shops, drying yard and rural godowns, installation of solar dryers are vital in selected APMCs based on the requirements and availability to attract more commodity arrivals and revenue generation. We also observed that the states with high level of reform scores are better performers in terms of attracting investments on various segments of the supply chain suggesting that complete implementation of APMC reforms would, no doubt, fetch expected outcome.

REFERENCES

Acharya, S.S. (2004). State of the Indian farmer, A millennium study on Agricultural Marketing, Department of Agricultural and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, and Academic Foundation, New Delhi.

Bala, B. (2009). Marketing efficiency of cooperative marketing societies in Himachal Pradesh: A case study of vegetables. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing.vol.23: pp: 99-108.

Bhoi B. Binod, Sujata Kundu, Vimal Kishore and D. Suganthi (2019). Supply chain dynamics and food inflation in India. RBI Bulletin. October 2019. pp: 95-111.

Chand, R. (2012). Development policies and agricultural markets. Economic and Political Weekly. Vol.47: pp: 53-63

Chand Ramesh and Jaspal Singh (2016). Study report on agricultural marketing and farmer friendly reforms across Indian States and UTs. National Institution for Transforming India, NITI Aayog, New Delhi, October, 2016.

Chengappa, P.G., A.V., Manjunatha, V. Dimble and K. Shah (2012). Competitive assessment of onion markets in India. Agricultural Development and Rural Transformation Centre Institute for Social and Economic Change, Nagarabhavi, Bangalore.

Down to Earth, Fortnightly Magazine, 17th January, 2018. The Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi, India. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/india-needs-30-000-agri-markets-to-give-fair-deal-to-farmers-59513.

GoI (2013), ‘Final Report of Committee of State Ministers, In-charge of Agriculture Marketing to Promote Reforms’, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture and Co-operation, Government of India, New Delhi.

ICAR-CIPHET. (2015). Assessment of quantitative harvest and post-harvest losses of major crops and commodities in India. ICAR, New Delhi.

Khunt, K., Vekariya, S., and Gajipara, H. (2008). Performance and problems of regulated markets in Gujarat. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, Vol.22(1). pp: 82-98.

National Agricultural Market, Small Farmers Agribuiness Consortium. Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.enam.gov.in

National Commission on Farmers Serving: Farmers and Saving Farming 2006: Year of Agricultural Renewal. Third Report. Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI.

National Paper -PLP-2020-21. Market linkages for Agricultural Commodities. pp: 1-8. National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development, Mumbai www.nabard.org.

Negi, D.S, P.S. Birthal, D. Roy and M.T. Khan (2018), ‘Farmers’ Choice of Market Channels and Producer Prices in India: Role of Transportation and Communication Networks’, Food Policy, Vol. 81, pp. 106-121.

NITI Policy Paper No.1/2017: Doubling of Farmers income Rationale, Strategy Prospects and Action Plan, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.agricoop.nic.in/en/doubling-farmers.

Ranjit Kumar, Sanjiv Kumar, PC Meena, B Ganesh Kumar and N Sivaramane (2021). Strengthening e-NAM in India: way forward. National Academy of Agricultural Research Management, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Reddy A. Amarender (2018). Electronic national agricultural markets: the way forward. Current Science. Vol 115(5). pp: 826 -837.

Report of the Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income (2017). Volume IV “Post-production interventions: Agricultural Marketing” Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers’ Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers. August. 2017.

Selvaraj, K. N, K.R.Ashok and R.Parimalarangan (2021). Feasibility study for improving the performance of regulated markets in Tamil nadu. Research Report/Policy Briefs. Department of Agricultural Marketing and Agribusiness, Government of Tamil Nadu.

Selvaraj, K.N., R.Parimalarangan and Susmitha Burigi (2022). E-trading facilities utilization pattern in regulated markets of Tamil nadu and feasibility of converting low/non-arrival regulated markets into primary processing centres. Agricultural Situation in India. Vol. LXXIX (2). pp:21-33.

Shilpi, F., and Umali-Deininger, D. (2007). Where to sell? market facilities and agricultural marketing. Policy Research Working Paper 4455. The World Bank.

Vaikunthe, L. (2000). Regulatory framework for agricultural marketing-a case study of APMCs in Karnataka. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing, Vol.14(3). pp: 1-7.

The draft model legislation titled the State Agricultural Produce Marketing (Development and Regulation) Act, 2003. Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.agricoop.nic.in/default/files/apmc, 2003.

The State/UT Agricultural Produce and Livestock Marketing (Promotion & Facilitation) Act, 2017, Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, GoI. www.agricoop.nic.in/default/files/ apmc, 2017.