ABSTRACT

Despite being small, mutton is an essential industry in Malaysia, as it provides an alternative source of protein to people. This country produces around 4,000 tons of mutton yearly, or only sufficient to supply approximately 11.5% of the local needs. Malaysia imports more than 50,000 live goats and sheep and more than 30,000 tons of mutton from other countries. Mutton is the least consumed type of meat in Malaysia. The annual consumption per capita has been constant at around 1.2 kg/person for the past five years, and the demand is expected to reduce yearly. Mutton is not an attractive industry for an entrepreneur to invest in this business. Nevertheless, the supply chain of mutton from farms or ports has created business opportunities for some entrepreneurs. The mutton supply chain is divided into four levels: farm or port, national wholesale, state or district wholesale, manufacturer or processor, and retailers before it reaches end users. The supply chains of mutton enable the entrepreneurs to generate income, maximize profit, and supply the mutton to the consumers.

Keywords: supply chain, small ruminants, mutton industry, challenges in mutton industry

INTRODUCTION

The livestock industry is an essential component of the agricultural sector in Malaysia, as it provides the largest source of protein to the population, offers job opportunities, and contributes to the country's economic development. It helps secure sustainable food and improves the health of the people. The livestock industry in Malaysia is worth more than RM10.00 (US$2.39) billion a year, including domestic production, exports and imports of live livestock, frozen meat, and processed products. The livestock industry is divided into two categories: ruminants and non-ruminants. The ruminant sub-industry is divided into two: large ruminants, including cattle and buffalo, and small ruminants, such as goats and sheep. Although the value is small, approximately around RM173.46 (US$41.30) million (1.73%) of the total value of the livestock industry), small ruminants are still needed in Malaysia. Small ruminants offer an alternative source of protein to Malaysians.

This paper discusses the mutton industry in Malaysia. It highlights the mutton supply chain from farms or ports (importing commodities) to consumers. It aims to identify issues and challenges faced by the industry in supplying the commodity to the consumers. The mutton supply in Malaysia greatly depends on the farms outside the country in line with the increased purchasing power and population growth (Hifzan et al., 2018). The size of the local breed is smaller than the imported animals, so Malaysia needs more live animals to supply to the local consumers. Lack of land is one factor that hinders the development of Malaysia's livestock industry. Furthermore, the local climate, which is humid and wet, is also not inclined to develop small ruminants.

MUTTON INDUSTRY IN MALAYSIA

Production

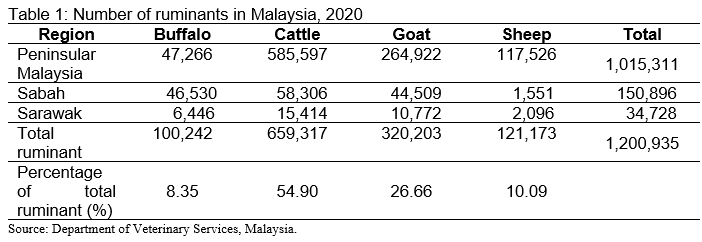

In general, mutton is a small industry in Malaysia. In 2020, the population of sheep and goats totaled around 441,000 heads, down from 478,500 in 2018. The number of animals represents approximately 36.75% of the total ruminants in Malaysia. However, these animals only contributed around 1.69% of the whole meat required by Malaysian consumers. Malaysia produced approximately 4,026.4 tons of mutton in 2020. Mutton production is very few compared to the domestic needs of 40,500 tons per year. Furthermore, red meat consumption in Malaysia is around 237,800 tons per year. The number of sheep and goats in comparison to other ruminants is presented in Table 1.

The number of goats and sheep has dropped significantly from year to year. For example, the number of goats has reduced from 416,530 in 2016 to around 320,000 animals in 2020. At the same time, the number of sheep also dropped from 138,480 animals to 121,170. One of the reasons for the reduction of animals is the close operation of small operators.

In general, goat breeds can be categorized into three functions, such as for meat production (Boer, Bean, Black Bengal, Savanna, Kalahari Red, and Jermasia breeds); for dairy (Alpine, Saanen, Toggenburg breeds), and dual function (for milk and meat) (Jamnapari and Anglo-Nubian breeds). High cost of production and less return on investment are two main factors that hinder the breeders from investing in goat/sheep breeding. Goat breeding is not an attractive business venture for investors in Malaysia. As a result, the number of breeders has reduced significantly. Farmers breed goats/sheep mainly for hobby or on a part-time basis.

Consumption

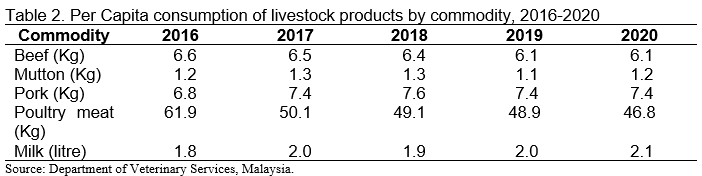

Mutton consumption has also slightly reduced from 35,686.7 tons in 2014 to 35,489.8 tons in 2020. Malaysian consumers generally do not favor mutton. The consumption per capita of mutton was only 1.2 kg/year in 2020, reduced from 1.3 kg/year in 2017. In comparison, the consumption per capita for beef was 6.1 kg/year, pork (7.4 kg/year), and poultry meat (53.6 kg/year) in the same year. Mutton is the least consumed type of meat in Malaysia. The consumption of meat in Malaysia is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that all meat consumption per capita has been constant for five years. The demand for mutton does not change much. The concern for healthy life seems to change the lifestyle and eating habits of Malaysian consumers. They prefer white meat more than red meat. The Malaysian people part take more fish in their diet. Malaysian people take more than 46.9 kg/year of fish, the second highest in Asia after Cambodia (63.2 kg/year).

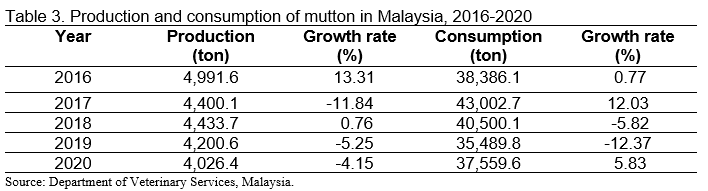

Many people perceive that mutton contains high cholesterol and will affect their health. Some consumers also don’t like the bad aroma of mutton, while others take mutton with precaution or in small amounts. On the other hand, scientific studies revealed that goat meat could reduce cholesterol levels in the blood, reducing the risk of atherosclerosis and heart disease, making it suitable for inclusion in a heart-healthy diet. The production and consumption of mutton are presented in Table 3.

The production of mutton has fluctuated due to a lack of live animals and is unable to supply the demand by local consumers. Table 3 shows that the production has dropped between -4.15% and -11.8% a year within five years. Consistent with the production, the consumption of mutton also decreased significantly. The consumption growth shows a negative trend in 2018 and 2019, with -5.82% and -12.37%, respectively. The drop in total consumption results from the decrease in consumption per capita from 1.3 kg/year in 2017 to 1.2 kg/year in 2020. The report from the Department of Statistics, Malaysia revealed that the consumption per capita dropped to 1.1 kg/year in 2021 (Statistics Malaysia, 2022). The perception that mutton contains high cholesterol and is not very good for health is one of the reasons for not part taking mutton. Another pushing factor is the price of mutton, which is relatively more expensive than other meats, such as beef and chicken.

Price also contributed to the decrease in demand for mutton. The price of local mutton has increased from RM26.80 (US$6.40)/kg in 2009 to RM41.85 (US$9.95)/kg. On the other hand, the imported mutton is also expensive and is sold at RM34.00 (US$8.10)/kg. Consumers have the option to shift their diets to other cheaper meats, such as local beef (RM32.00 (US$7.60)/kg) or imported beef (RM21.90 (US$5.20)/kg), or chicken (RM9.00 (US$2.15)/kg).

Trading

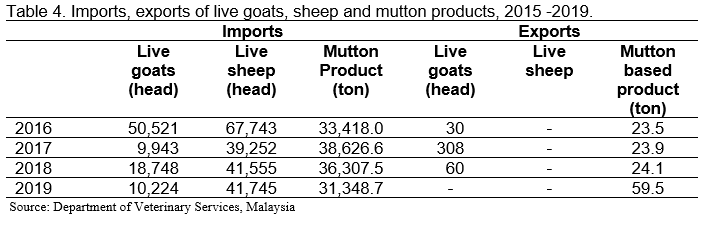

Malaysia still depends on its mutton from foreign countries as its self-sufficiency level for mutton is only 11.36%. Malaysia imports more than 60,300 live goats and sheep from various countries, especially Australia, New Zealand, Africa, and India. At the same time, Malaysia also imports more than 31,348 tons of frozen and processed mutton, valued at more than RM679.48 (US$161.78) million. Despite the lack of production, Malaysia is also exporting its mutton-based products. Malaysia exports more than 59.5 tons of fresh and processed mutton, valued at more than RM1.11 (US$0.264) million, in 2019. The data on the import and export of goats, sheep, and mutton products is presented in Table 4.

Malaysia exported live animals to neighboring countries such as Thailand and Brunei; and processed products to many countries, especially Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong, and Timor-Leste. Malaysia exports products in the categories of frozen lamb carcasses, fresh or chilled boneless cut sheep, and fresh or chilled cuts of sheep, with bone or without bone. In 2020, Malaysia's exported mutton value was around US$0.14 million, reduced from US$0.95 million or -85.25% in 2018.

Marketing chain

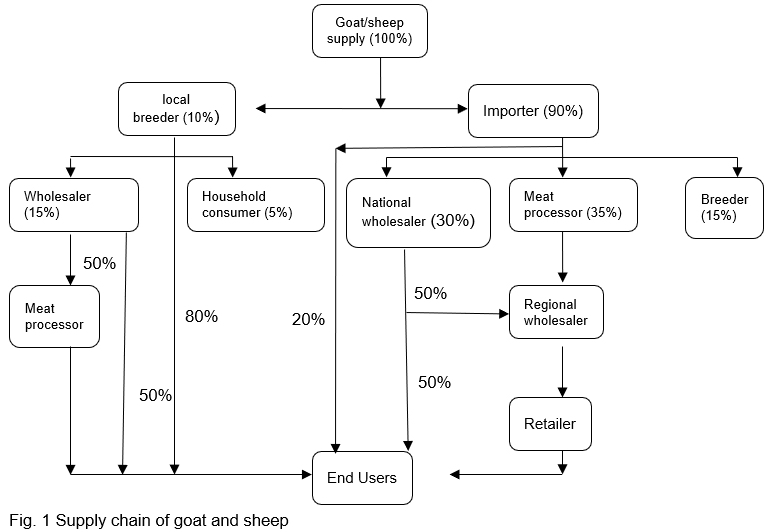

The value chain provides valuable information to understand the elements and stages involved from production to consumption, including the services involved in a business, including input materials, supply, production, handling, transportation, and processing. The marketing chain involves rural, urban, and international markets, and this chain will connect farmers with markets and marketing systems (Devendra, 2015). The marketing value chain from the farm or port to the consumer needs to be identified to know the real situation of Malaysia's goat/sheep industry. The mutton meat marketing chain is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the goats/sheep supply chain in Peninsular Malaysia. The marketing channel indicates the supply source from the breeder/importer to consumers. It generally contains four layers: breeders/importers, wholesalers, processors, and retailers. Almost 90% of mutton supply is from abroad, while domestic supply is only around 10%. This figure shows a very high dependence on imported sources. Local breeders sell almost 80% of live goats/sheep directly to end users, especially for aqikah and sacrifice by Muslim consumers. Aqikah refers to the slaughter of a goat or sheep as a sign of gratitude by Muslims when they obtain a new child. Islam prescribes that a parent needs to slaughter two goats/sheep if they get a boy or one goat/sheep if they get a girl. On the other hand, animal sacrifice is a religious duty in Islam. It is done on the 10th day of Eid Adha in Zulhijjah in the Islamic calendar to commemorate the submission of Prophet Ibrahim to the Divine Command to sacrifice his son, Prophet Ismail.

Meanwhile, 15% of live goats/sheep sales are made through wholesalers, and the remaining 5% of this livestock is sold directly to household users. The wholesaler sells around 50% of the meat directly to end users, while another 50% to the meat processors. Meat processors refer to small industry players that process meat into processed products, such as meatballs, burgers, and frankfurter.

The other cluster refers to live goats/sheep from importers. The supply of live sheep and goats is insufficient for local consumption. Thus, Malaysia imports live sheep and goats from other countries, mainly from New Zealand and Australia. Malaysia also imported live animals from Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia. Marketing channels from importers involve four groups consisting of processors (35%), wholesalers (30%), end users (20%), and local breeders (15%). Approximately 85% of the imported live goats/sheep are slaughtered, while the remaining 15% are sold for breeding. First-level wholesalers or national wholesalers distribute mutton supplies to second-level wholesalers (50%) in the state and district and end users (50%). End users buy live livestock from importers for aqiqah and Eid Adha purposes, while wholesalers and processors buy live livestock or frozen meat to be distributed to retailers. The processor refers to manufacturers or small and medium enterprises involved in the added value products, such as burgers, frozen food, and other products.

Some breeders imported premium goats/sheep from Australia for breeding with local breeds. They crossbreed the premium male goat or ram with the local ewe breed. The crossbreed animals are usually bigger and have a better quality of meat.

Marketing channel of imported frozen meat

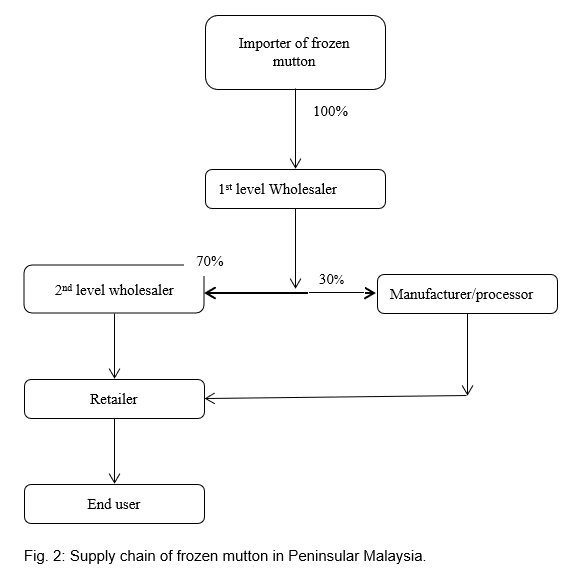

Malaysia also imports frozen meat from countries that include New Zealand, Australia, Bangladesh, and India. Malaysia only imports meat from certified halal slaughterhouses in countries. The Department of Islamic Development Malaysia, popularly known as JAKIM, will certify the slaughterhouse before the Malaysian companies apply for the Approval Permit (AP). The importing companies from Malaysia must present the halal certificate from the country's Halal Certification Institution before the Department of Veterinary Services produces the imported permit. Halal certification is critical because more than 65% of the end-users in Malaysia are Muslims. The supply chain of frozen mutton in Malaysia is presented in Figure 2.

Almost 100% of imported frozen meat is marketed through first-level wholesalers (national). Then, the national wholesaler sells approximately 70% of the mutton to second-level wholesalers before being sold to retailers and end users. At the same time, the national wholesalers sell the remaining 30% of frozen meat directly to industrial consumers who manufacture meat for value-added products.

Marketing margin of mutton

Marketing margin is the difference between a product’s purchase and selling price. The term “marketing margin” is used because it is often the job of a distributor or other third party to do marketing and advertising for the product, even if it is not the actual producer of the product. People trade mutton to maximize profit. At the same time, the success of a business is also determined by consumer satisfaction.

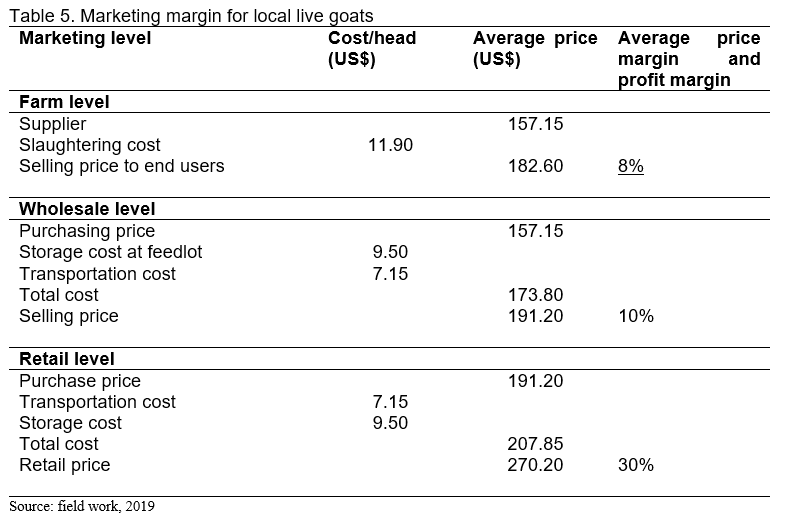

Local live goats

Most local breeders in Malaysia are small-scale operators. The goat breeds in Malaysia comprise small-framed animals made up of the original Katjang goat, with the addition of larger-framed exotic goats such as Jamnapari and Boer. The local indigenous Katjang goat has a reasonably high degree of tolerance to the local environment. On the other hand, the Boer, Jamnapari, and Savanna, which are breeds from other countries, are well adapted in Malaysia. The average size of a Katjang goat is 25-30kg. In comparison, the average weight of a Boar goat is between 35 and 45 kilograms. On the other hand, an adult Boar goat can weigh between 90 and 150 kilograms. The marketing margin for local goats is presented in Table 5.

The average price at the farm level for a local goat with an average weight of 35.00 kg is US$157.15/head. Considering the slaughtering cost of US$11.90 each, the selling price of goats slaughtered at the farm is US$169.04/head. With a profit margin of 8%/head, the selling price at the farm level to the end user is as much as US$182.60/head if the end users purchase directly from the breeder. Some wholesalers buy the animals from the breeders and sell it to retailers. The wholesaler's profit margin is about 10% of the purchase price, transportation, and storage costs. Therefore, the wholesale price is as much as US$191.20/head. The retailers make a 30% profit margin and sell the live goat for between US$270.20 and US$309.50. Some retailers provide slaughtering and cooking services to consumers, but they have to pay additional charges.

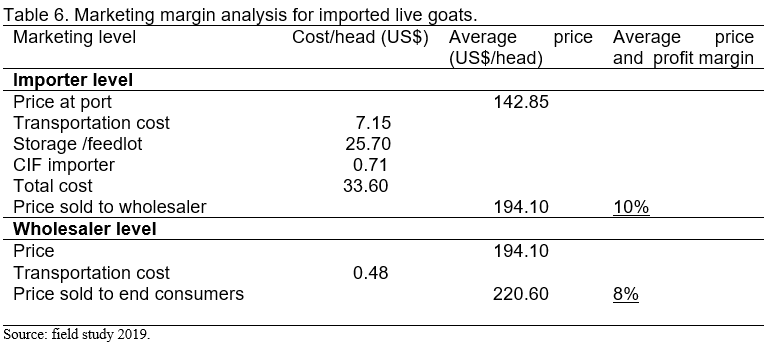

Imported live goats/sheep

Most imported live goats/sheep are slaughtered for meat. Only around 15% of the goats/sheep are used for breeding. The average price of imported live goats from Australia is US$142.85/head at the Malaysia port. Goats and sheep are imported by ship to reduce the cost of transportation. Sometimes, the importer uses air freight when the demand is high, such as during the Muslim festival. On average, importers charge transport costs of US$7.14/head, storage costs in the feedlot US$25.70, and Cost, Insurance, and Freight (CIF) charges US$0.71, making a profit of 10%. The price of a live goat sold to wholesalers amounted to US$194.10. The wholesaler, on average, charges US$0.48/head for transportation costs. Considering a profit margin of 8%, the market price of imported live goats is US$220.60/head. Marketing margin analysis for imported live goats is as in Table 6.

This marketing margin analysis shows that the price of imported goats is relatively lower than that of local goats. People preferred the imported live goats and sheep because the price is lower and the quality of meat is better than that of the local one.

Frozen mutton

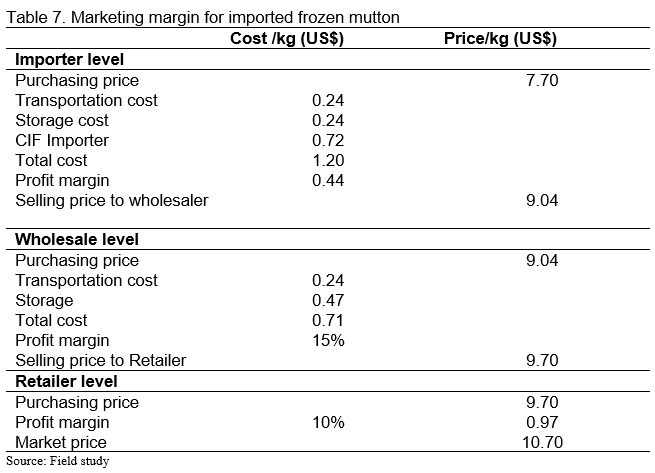

The importers also import frozen mutton from overseas markets. The products come in the form of carcasses or body parts meats. The price of a carcass goat is usually lower than the cut mutton. The average price of a frozen carcass goat is US$190.50. On the other hand, the average price of cut mutton at the importer level is US$7.70/kg (including transport costs, importer's CIF, and 5% profit margin).

Meanwhile, the wholesale price is US$9.04/kg (including storage and transportation costs), with a profit margin of 15%. The retail price is US$10.70/kg with a profit margin of 10%. The marketing margin for frozen mutton is presented in Table 7.

Consumer behavior toward mutton

Mat Amin et. al. (2019) conducted a study to understand consumers' perceptions toward mutton in Malaysia. The study revealed that about 43% of the respondents could not differentiate between mutton goats and sheep, while 34% did not bother about whether its goats or sheep. Around 64% of the respondents are aware of the benefits of mutton. However, most consumers do not favor the purchasing and consuming of mutton. About 44.4% of the respondents seldom buy mutton once within six months or once a year. Those who purchase mutton always obtain the supply from agro-market (52.42%) and supermarkets (29.84%). The statistic shows that the consumption per capita for mutton has been consistent at 1.1 kg/year for the past five years. The study revealed that about 28.3% of the respondents take mutton once a month, one time in two months (12.64%), within six months (11.55%), and 11.55% in a year. They seldom purchase and cook mutton at home. Around 37.90% take ready-to-eat or cooked mutton at the restaurant or during festivals where the organizer serves the food.

Several factors hinder consumers from partaking in mutton, such as not favoring its bad aroma, health reasons, cultural value, unpleasant taste, and high price. Respondents who have related health problems believed that eating mutton could cause high blood pressure and increase the cholesterol content in the body. In reality, the saturated fat content in goat’s meat is lower than that of beef, pork, and chicken. Therefore, mutton is a healthy alternative source of protein for Malaysians.

CHALLENGES IN MUTTON SUPPLY CHAIN

Mutton is an important industry as it is one of Malaysia's alternative protein sources. More than 300,000 people are involved in the industry, including breeders, suppliers, importers, wholesalers, and retailers. This industry also created a business opportunity for entrepreneurs and developed the socioeconomic of the people. Nevertheless, this industry is also facing many issues and challenges. The expertise in goat farming in Malaysia does not seem to stand out like that in other livestock. The latest information on goat farming is also less available from the organization concerned. The network of goat breeders is essential so that the flow of information is always obtained. Farmers also need to take the initiative to learn and find information about goat farming. Although the expertise in Malaysia is lacking, we can still use the expertise of foreign countries that conduct a lot of research on goat farming.

The problem of animal husbandry is the difficulty of obtaining goat’s feed. When the number of livestock is increasing, the issue of raising goats that farmers usually face is getting feed sources. Sufficient feed sources are mandatory to ensure the growth of each goat. Some breeders do not care about this matter. The meaning here is that they have no feed plan for their livestock for the coming days. When they face this problem, they start looking for an easy way out by releasing their livestock to find feed. The main feed for goats is grass. Ideally, grass storage should be sufficient for the next few months to ensure that there is no problem of running out of grass. There are many other alternatives besides giving fodder as goat’s feed.

The lack of veterinary facilities in the field condition is the major drawback for health care issues. Many goat farmers are suffering from diseases. Raising goats is impossible to escape the problem of raising diseased goats. Most of the diseases that often attack livestock are flatulence. If not controlled as early as possible, infected livestock can spread to other livestock. The cause of this infection is due to the goat overeating feed containing nitrogen. One example of high nitrogen feed is beans.

The industry is also facing a lack of financial aid. The goat farming industry is not new and has been in Malaysia for a long time. But many financial institutions are afraid to provide financial assistance to goat farmers. The lack of financial aid from the government and financial institutions resulted in a lack of people participating in this industry.

FUTURE DIRECTION

The livestock sub-sector is projected to contribute to gross domestic product (GDP) at a cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) of 6.00%, from RM17.15 (US$4.08) billion in 2021 to RM28.98 (US$6.90) billion in 2030. The sub-sector is also expected to contribute between 32.38% and 36.40% to the total GDP of the agro-food sector from 2021 to 2030. Under the National Agri-food Policy (NAP 2.0), the government emphasizes the industry in which Malaysia has a comparative advantage, such as broiler, eggs and pork, and beef. The government puts less emphasis on the development of the mutton industry. The NAP 2.0 does not spell out precisely the strategy and action plan for the mutton industry. The general objectives for the ruminant sector are as follows:

- Achieve the self-sufficiency level (SSL) target of 50% for beef and 100% for fresh milk;

- Increase the total number of ruminant livestock; and

- Increase the level of ruminant-oil palm integration

This strategy aims to ensure that the livestock sub-sector has alternatives and is not exposed to the uncertainty of the price of imported foods. For example, most of the cost of raising ruminants can be traced back to feed. Due to the difficulty of growing fodder such as corn locally due to the humidity and uncertainty during rainy season, the country had to import to meet the animal feed needs. In this regard, Palm Oil Kernels (PKC) have been identified as a cost-effective feed substitute for livestock and can be produced in large quantities due to the country's position as one of the leading palm oil producers. In addition, the correct formulation of feed ingredients is essential in achieving the optimal ratio of feed ingredients used to increase livestock weight. In addition, incentives for producing local animal feed materials will be encouraged to attract local investors and entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Mohd Zaffrie Mat Amin, Hairazi, Mohd Amirul, Mohd Tarmizi and Azahar (2019). Kajian rantaian bekalan dan penggunaan daging kambing dan biri-biri di Semenanjung malaysia - kajian kes. Laporan Kajian Sosioekonomi 2019. Pusat Penyelidikan enokonomi, Risikan Pasaran dan Agribusiness, MARDI.

Hifzan, R.M., Nor Amna A’liah M.N., Izuan Bahtiar, A.J., Amie Mariani A.B. dan Mohd Hafiz, A.W. (2018). Manipulasi kambing Katjang bagi menjamin kelestarian industri ruminan kecil di Malaysia. Buletin Teknologi MARDI Bil. 16 (2019) Khas Ternakan Lestari: 1 – 10

Devendra, C. (2015) Dynamics of Goat Meat Production in Extensive Systems in Asia: Improvement of Productivity and Transformation of Livelihoods. Agrotechnol 4:131. doi:10.4172/2168-9881.1000131

Department of Veterinary Services. (2019). Livestock statistics. Diperoleh pada 20 Disember 2019 dari http://agrolink.moa.my/jph/dvs/statistics/statidx.html

Supply Chain of Mutton in Malaysia: Challenges and the Way Forward

ABSTRACT

Despite being small, mutton is an essential industry in Malaysia, as it provides an alternative source of protein to people. This country produces around 4,000 tons of mutton yearly, or only sufficient to supply approximately 11.5% of the local needs. Malaysia imports more than 50,000 live goats and sheep and more than 30,000 tons of mutton from other countries. Mutton is the least consumed type of meat in Malaysia. The annual consumption per capita has been constant at around 1.2 kg/person for the past five years, and the demand is expected to reduce yearly. Mutton is not an attractive industry for an entrepreneur to invest in this business. Nevertheless, the supply chain of mutton from farms or ports has created business opportunities for some entrepreneurs. The mutton supply chain is divided into four levels: farm or port, national wholesale, state or district wholesale, manufacturer or processor, and retailers before it reaches end users. The supply chains of mutton enable the entrepreneurs to generate income, maximize profit, and supply the mutton to the consumers.

Keywords: supply chain, small ruminants, mutton industry, challenges in mutton industry

INTRODUCTION

The livestock industry is an essential component of the agricultural sector in Malaysia, as it provides the largest source of protein to the population, offers job opportunities, and contributes to the country's economic development. It helps secure sustainable food and improves the health of the people. The livestock industry in Malaysia is worth more than RM10.00 (US$2.39) billion a year, including domestic production, exports and imports of live livestock, frozen meat, and processed products. The livestock industry is divided into two categories: ruminants and non-ruminants. The ruminant sub-industry is divided into two: large ruminants, including cattle and buffalo, and small ruminants, such as goats and sheep. Although the value is small, approximately around RM173.46 (US$41.30) million (1.73%) of the total value of the livestock industry), small ruminants are still needed in Malaysia. Small ruminants offer an alternative source of protein to Malaysians.

This paper discusses the mutton industry in Malaysia. It highlights the mutton supply chain from farms or ports (importing commodities) to consumers. It aims to identify issues and challenges faced by the industry in supplying the commodity to the consumers. The mutton supply in Malaysia greatly depends on the farms outside the country in line with the increased purchasing power and population growth (Hifzan et al., 2018). The size of the local breed is smaller than the imported animals, so Malaysia needs more live animals to supply to the local consumers. Lack of land is one factor that hinders the development of Malaysia's livestock industry. Furthermore, the local climate, which is humid and wet, is also not inclined to develop small ruminants.

MUTTON INDUSTRY IN MALAYSIA

Production

In general, mutton is a small industry in Malaysia. In 2020, the population of sheep and goats totaled around 441,000 heads, down from 478,500 in 2018. The number of animals represents approximately 36.75% of the total ruminants in Malaysia. However, these animals only contributed around 1.69% of the whole meat required by Malaysian consumers. Malaysia produced approximately 4,026.4 tons of mutton in 2020. Mutton production is very few compared to the domestic needs of 40,500 tons per year. Furthermore, red meat consumption in Malaysia is around 237,800 tons per year. The number of sheep and goats in comparison to other ruminants is presented in Table 1.

The number of goats and sheep has dropped significantly from year to year. For example, the number of goats has reduced from 416,530 in 2016 to around 320,000 animals in 2020. At the same time, the number of sheep also dropped from 138,480 animals to 121,170. One of the reasons for the reduction of animals is the close operation of small operators.

In general, goat breeds can be categorized into three functions, such as for meat production (Boer, Bean, Black Bengal, Savanna, Kalahari Red, and Jermasia breeds); for dairy (Alpine, Saanen, Toggenburg breeds), and dual function (for milk and meat) (Jamnapari and Anglo-Nubian breeds). High cost of production and less return on investment are two main factors that hinder the breeders from investing in goat/sheep breeding. Goat breeding is not an attractive business venture for investors in Malaysia. As a result, the number of breeders has reduced significantly. Farmers breed goats/sheep mainly for hobby or on a part-time basis.

Consumption

Mutton consumption has also slightly reduced from 35,686.7 tons in 2014 to 35,489.8 tons in 2020. Malaysian consumers generally do not favor mutton. The consumption per capita of mutton was only 1.2 kg/year in 2020, reduced from 1.3 kg/year in 2017. In comparison, the consumption per capita for beef was 6.1 kg/year, pork (7.4 kg/year), and poultry meat (53.6 kg/year) in the same year. Mutton is the least consumed type of meat in Malaysia. The consumption of meat in Malaysia is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that all meat consumption per capita has been constant for five years. The demand for mutton does not change much. The concern for healthy life seems to change the lifestyle and eating habits of Malaysian consumers. They prefer white meat more than red meat. The Malaysian people part take more fish in their diet. Malaysian people take more than 46.9 kg/year of fish, the second highest in Asia after Cambodia (63.2 kg/year).

Many people perceive that mutton contains high cholesterol and will affect their health. Some consumers also don’t like the bad aroma of mutton, while others take mutton with precaution or in small amounts. On the other hand, scientific studies revealed that goat meat could reduce cholesterol levels in the blood, reducing the risk of atherosclerosis and heart disease, making it suitable for inclusion in a heart-healthy diet. The production and consumption of mutton are presented in Table 3.

The production of mutton has fluctuated due to a lack of live animals and is unable to supply the demand by local consumers. Table 3 shows that the production has dropped between -4.15% and -11.8% a year within five years. Consistent with the production, the consumption of mutton also decreased significantly. The consumption growth shows a negative trend in 2018 and 2019, with -5.82% and -12.37%, respectively. The drop in total consumption results from the decrease in consumption per capita from 1.3 kg/year in 2017 to 1.2 kg/year in 2020. The report from the Department of Statistics, Malaysia revealed that the consumption per capita dropped to 1.1 kg/year in 2021 (Statistics Malaysia, 2022). The perception that mutton contains high cholesterol and is not very good for health is one of the reasons for not part taking mutton. Another pushing factor is the price of mutton, which is relatively more expensive than other meats, such as beef and chicken.

Price also contributed to the decrease in demand for mutton. The price of local mutton has increased from RM26.80 (US$6.40)/kg in 2009 to RM41.85 (US$9.95)/kg. On the other hand, the imported mutton is also expensive and is sold at RM34.00 (US$8.10)/kg. Consumers have the option to shift their diets to other cheaper meats, such as local beef (RM32.00 (US$7.60)/kg) or imported beef (RM21.90 (US$5.20)/kg), or chicken (RM9.00 (US$2.15)/kg).

Trading

Malaysia still depends on its mutton from foreign countries as its self-sufficiency level for mutton is only 11.36%. Malaysia imports more than 60,300 live goats and sheep from various countries, especially Australia, New Zealand, Africa, and India. At the same time, Malaysia also imports more than 31,348 tons of frozen and processed mutton, valued at more than RM679.48 (US$161.78) million. Despite the lack of production, Malaysia is also exporting its mutton-based products. Malaysia exports more than 59.5 tons of fresh and processed mutton, valued at more than RM1.11 (US$0.264) million, in 2019. The data on the import and export of goats, sheep, and mutton products is presented in Table 4.

Malaysia exported live animals to neighboring countries such as Thailand and Brunei; and processed products to many countries, especially Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong, and Timor-Leste. Malaysia exports products in the categories of frozen lamb carcasses, fresh or chilled boneless cut sheep, and fresh or chilled cuts of sheep, with bone or without bone. In 2020, Malaysia's exported mutton value was around US$0.14 million, reduced from US$0.95 million or -85.25% in 2018.

Marketing chain

The value chain provides valuable information to understand the elements and stages involved from production to consumption, including the services involved in a business, including input materials, supply, production, handling, transportation, and processing. The marketing chain involves rural, urban, and international markets, and this chain will connect farmers with markets and marketing systems (Devendra, 2015). The marketing value chain from the farm or port to the consumer needs to be identified to know the real situation of Malaysia's goat/sheep industry. The mutton meat marketing chain is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the goats/sheep supply chain in Peninsular Malaysia. The marketing channel indicates the supply source from the breeder/importer to consumers. It generally contains four layers: breeders/importers, wholesalers, processors, and retailers. Almost 90% of mutton supply is from abroad, while domestic supply is only around 10%. This figure shows a very high dependence on imported sources. Local breeders sell almost 80% of live goats/sheep directly to end users, especially for aqikah and sacrifice by Muslim consumers. Aqikah refers to the slaughter of a goat or sheep as a sign of gratitude by Muslims when they obtain a new child. Islam prescribes that a parent needs to slaughter two goats/sheep if they get a boy or one goat/sheep if they get a girl. On the other hand, animal sacrifice is a religious duty in Islam. It is done on the 10th day of Eid Adha in Zulhijjah in the Islamic calendar to commemorate the submission of Prophet Ibrahim to the Divine Command to sacrifice his son, Prophet Ismail.

Meanwhile, 15% of live goats/sheep sales are made through wholesalers, and the remaining 5% of this livestock is sold directly to household users. The wholesaler sells around 50% of the meat directly to end users, while another 50% to the meat processors. Meat processors refer to small industry players that process meat into processed products, such as meatballs, burgers, and frankfurter.

The other cluster refers to live goats/sheep from importers. The supply of live sheep and goats is insufficient for local consumption. Thus, Malaysia imports live sheep and goats from other countries, mainly from New Zealand and Australia. Malaysia also imported live animals from Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia. Marketing channels from importers involve four groups consisting of processors (35%), wholesalers (30%), end users (20%), and local breeders (15%). Approximately 85% of the imported live goats/sheep are slaughtered, while the remaining 15% are sold for breeding. First-level wholesalers or national wholesalers distribute mutton supplies to second-level wholesalers (50%) in the state and district and end users (50%). End users buy live livestock from importers for aqiqah and Eid Adha purposes, while wholesalers and processors buy live livestock or frozen meat to be distributed to retailers. The processor refers to manufacturers or small and medium enterprises involved in the added value products, such as burgers, frozen food, and other products.

Some breeders imported premium goats/sheep from Australia for breeding with local breeds. They crossbreed the premium male goat or ram with the local ewe breed. The crossbreed animals are usually bigger and have a better quality of meat.

Marketing channel of imported frozen meat

Malaysia also imports frozen meat from countries that include New Zealand, Australia, Bangladesh, and India. Malaysia only imports meat from certified halal slaughterhouses in countries. The Department of Islamic Development Malaysia, popularly known as JAKIM, will certify the slaughterhouse before the Malaysian companies apply for the Approval Permit (AP). The importing companies from Malaysia must present the halal certificate from the country's Halal Certification Institution before the Department of Veterinary Services produces the imported permit. Halal certification is critical because more than 65% of the end-users in Malaysia are Muslims. The supply chain of frozen mutton in Malaysia is presented in Figure 2.

Almost 100% of imported frozen meat is marketed through first-level wholesalers (national). Then, the national wholesaler sells approximately 70% of the mutton to second-level wholesalers before being sold to retailers and end users. At the same time, the national wholesalers sell the remaining 30% of frozen meat directly to industrial consumers who manufacture meat for value-added products.

Marketing margin of mutton

Marketing margin is the difference between a product’s purchase and selling price. The term “marketing margin” is used because it is often the job of a distributor or other third party to do marketing and advertising for the product, even if it is not the actual producer of the product. People trade mutton to maximize profit. At the same time, the success of a business is also determined by consumer satisfaction.

Local live goats

Most local breeders in Malaysia are small-scale operators. The goat breeds in Malaysia comprise small-framed animals made up of the original Katjang goat, with the addition of larger-framed exotic goats such as Jamnapari and Boer. The local indigenous Katjang goat has a reasonably high degree of tolerance to the local environment. On the other hand, the Boer, Jamnapari, and Savanna, which are breeds from other countries, are well adapted in Malaysia. The average size of a Katjang goat is 25-30kg. In comparison, the average weight of a Boar goat is between 35 and 45 kilograms. On the other hand, an adult Boar goat can weigh between 90 and 150 kilograms. The marketing margin for local goats is presented in Table 5.

The average price at the farm level for a local goat with an average weight of 35.00 kg is US$157.15/head. Considering the slaughtering cost of US$11.90 each, the selling price of goats slaughtered at the farm is US$169.04/head. With a profit margin of 8%/head, the selling price at the farm level to the end user is as much as US$182.60/head if the end users purchase directly from the breeder. Some wholesalers buy the animals from the breeders and sell it to retailers. The wholesaler's profit margin is about 10% of the purchase price, transportation, and storage costs. Therefore, the wholesale price is as much as US$191.20/head. The retailers make a 30% profit margin and sell the live goat for between US$270.20 and US$309.50. Some retailers provide slaughtering and cooking services to consumers, but they have to pay additional charges.

Imported live goats/sheep

Most imported live goats/sheep are slaughtered for meat. Only around 15% of the goats/sheep are used for breeding. The average price of imported live goats from Australia is US$142.85/head at the Malaysia port. Goats and sheep are imported by ship to reduce the cost of transportation. Sometimes, the importer uses air freight when the demand is high, such as during the Muslim festival. On average, importers charge transport costs of US$7.14/head, storage costs in the feedlot US$25.70, and Cost, Insurance, and Freight (CIF) charges US$0.71, making a profit of 10%. The price of a live goat sold to wholesalers amounted to US$194.10. The wholesaler, on average, charges US$0.48/head for transportation costs. Considering a profit margin of 8%, the market price of imported live goats is US$220.60/head. Marketing margin analysis for imported live goats is as in Table 6.

This marketing margin analysis shows that the price of imported goats is relatively lower than that of local goats. People preferred the imported live goats and sheep because the price is lower and the quality of meat is better than that of the local one.

Frozen mutton

The importers also import frozen mutton from overseas markets. The products come in the form of carcasses or body parts meats. The price of a carcass goat is usually lower than the cut mutton. The average price of a frozen carcass goat is US$190.50. On the other hand, the average price of cut mutton at the importer level is US$7.70/kg (including transport costs, importer's CIF, and 5% profit margin).

Meanwhile, the wholesale price is US$9.04/kg (including storage and transportation costs), with a profit margin of 15%. The retail price is US$10.70/kg with a profit margin of 10%. The marketing margin for frozen mutton is presented in Table 7.

Consumer behavior toward mutton

Mat Amin et. al. (2019) conducted a study to understand consumers' perceptions toward mutton in Malaysia. The study revealed that about 43% of the respondents could not differentiate between mutton goats and sheep, while 34% did not bother about whether its goats or sheep. Around 64% of the respondents are aware of the benefits of mutton. However, most consumers do not favor the purchasing and consuming of mutton. About 44.4% of the respondents seldom buy mutton once within six months or once a year. Those who purchase mutton always obtain the supply from agro-market (52.42%) and supermarkets (29.84%). The statistic shows that the consumption per capita for mutton has been consistent at 1.1 kg/year for the past five years. The study revealed that about 28.3% of the respondents take mutton once a month, one time in two months (12.64%), within six months (11.55%), and 11.55% in a year. They seldom purchase and cook mutton at home. Around 37.90% take ready-to-eat or cooked mutton at the restaurant or during festivals where the organizer serves the food.

Several factors hinder consumers from partaking in mutton, such as not favoring its bad aroma, health reasons, cultural value, unpleasant taste, and high price. Respondents who have related health problems believed that eating mutton could cause high blood pressure and increase the cholesterol content in the body. In reality, the saturated fat content in goat’s meat is lower than that of beef, pork, and chicken. Therefore, mutton is a healthy alternative source of protein for Malaysians.

CHALLENGES IN MUTTON SUPPLY CHAIN

Mutton is an important industry as it is one of Malaysia's alternative protein sources. More than 300,000 people are involved in the industry, including breeders, suppliers, importers, wholesalers, and retailers. This industry also created a business opportunity for entrepreneurs and developed the socioeconomic of the people. Nevertheless, this industry is also facing many issues and challenges. The expertise in goat farming in Malaysia does not seem to stand out like that in other livestock. The latest information on goat farming is also less available from the organization concerned. The network of goat breeders is essential so that the flow of information is always obtained. Farmers also need to take the initiative to learn and find information about goat farming. Although the expertise in Malaysia is lacking, we can still use the expertise of foreign countries that conduct a lot of research on goat farming.

The problem of animal husbandry is the difficulty of obtaining goat’s feed. When the number of livestock is increasing, the issue of raising goats that farmers usually face is getting feed sources. Sufficient feed sources are mandatory to ensure the growth of each goat. Some breeders do not care about this matter. The meaning here is that they have no feed plan for their livestock for the coming days. When they face this problem, they start looking for an easy way out by releasing their livestock to find feed. The main feed for goats is grass. Ideally, grass storage should be sufficient for the next few months to ensure that there is no problem of running out of grass. There are many other alternatives besides giving fodder as goat’s feed.

The lack of veterinary facilities in the field condition is the major drawback for health care issues. Many goat farmers are suffering from diseases. Raising goats is impossible to escape the problem of raising diseased goats. Most of the diseases that often attack livestock are flatulence. If not controlled as early as possible, infected livestock can spread to other livestock. The cause of this infection is due to the goat overeating feed containing nitrogen. One example of high nitrogen feed is beans.

The industry is also facing a lack of financial aid. The goat farming industry is not new and has been in Malaysia for a long time. But many financial institutions are afraid to provide financial assistance to goat farmers. The lack of financial aid from the government and financial institutions resulted in a lack of people participating in this industry.

FUTURE DIRECTION

The livestock sub-sector is projected to contribute to gross domestic product (GDP) at a cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) of 6.00%, from RM17.15 (US$4.08) billion in 2021 to RM28.98 (US$6.90) billion in 2030. The sub-sector is also expected to contribute between 32.38% and 36.40% to the total GDP of the agro-food sector from 2021 to 2030. Under the National Agri-food Policy (NAP 2.0), the government emphasizes the industry in which Malaysia has a comparative advantage, such as broiler, eggs and pork, and beef. The government puts less emphasis on the development of the mutton industry. The NAP 2.0 does not spell out precisely the strategy and action plan for the mutton industry. The general objectives for the ruminant sector are as follows:

This strategy aims to ensure that the livestock sub-sector has alternatives and is not exposed to the uncertainty of the price of imported foods. For example, most of the cost of raising ruminants can be traced back to feed. Due to the difficulty of growing fodder such as corn locally due to the humidity and uncertainty during rainy season, the country had to import to meet the animal feed needs. In this regard, Palm Oil Kernels (PKC) have been identified as a cost-effective feed substitute for livestock and can be produced in large quantities due to the country's position as one of the leading palm oil producers. In addition, the correct formulation of feed ingredients is essential in achieving the optimal ratio of feed ingredients used to increase livestock weight. In addition, incentives for producing local animal feed materials will be encouraged to attract local investors and entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Mohd Zaffrie Mat Amin, Hairazi, Mohd Amirul, Mohd Tarmizi and Azahar (2019). Kajian rantaian bekalan dan penggunaan daging kambing dan biri-biri di Semenanjung malaysia - kajian kes. Laporan Kajian Sosioekonomi 2019. Pusat Penyelidikan enokonomi, Risikan Pasaran dan Agribusiness, MARDI.

Hifzan, R.M., Nor Amna A’liah M.N., Izuan Bahtiar, A.J., Amie Mariani A.B. dan Mohd Hafiz, A.W. (2018). Manipulasi kambing Katjang bagi menjamin kelestarian industri ruminan kecil di Malaysia. Buletin Teknologi MARDI Bil. 16 (2019) Khas Ternakan Lestari: 1 – 10

Devendra, C. (2015) Dynamics of Goat Meat Production in Extensive Systems in Asia: Improvement of Productivity and Transformation of Livelihoods. Agrotechnol 4:131. doi:10.4172/2168-9881.1000131

Department of Veterinary Services. (2019). Livestock statistics. Diperoleh pada 20 Disember 2019 dari http://agrolink.moa.my/jph/dvs/statistics/statidx.html