ABSTRACT

The sustainable food system is dynamics process where the achievement of current food security will not hamper the capability of future generation to secure their food. The concept of healthy diets and circular economy approaches to reduce food loss and waste is addressed in the sustainable food system framework. Relate to this concept, circular agriculture is well known in Indonesia. It has been translated into sustainable and integrated farming system. Circular agriculture gives more benefits to farmers welfare than linear agriculture. Reinventing this concept by enhancing collaboration among agricultural stakeholders that is improving patron-client system between smallholder farmers and business is one of enablers factors in the transition of linear model business to circular model business. This study explores the relation between promoting eight principles of sustainable food system, encouraging Indonesian families to follow dietary plan, and reinventing circular agriculture. Circulating agricultural waste into new product or a source of energy could help unfortunate households to get decent livelihood and fulfilling nutritional intake for children. Hence, governance of food security by adopting circular agriculture to manage food loss and waste is simple action in the loop of complexity of sustainable food system. The holistic and inclusive approach of sustainable food system could reduce unhealthy diets across Indonesia families. The policy implementation to enabling these three aspects is not enough by launching regulation in taxes and subsidies, incentive and disincentive scheme, or other financial support system. The collaboration across farmer’s stakeholder in bio-conversion, research and development, and changes producer and consumer behaviors in the acceptance of bio-conversion product are also important. Early education on the important issues in promoting circular agriculture, healthy diets and food system at all stage level of education shall be prioritized in the government agenda.

Keywords: Circular Agriculture, Food Security, Healthy Diets.

INTRODUCTION

The overall score of Global Food Security Index (GPSI) for Indonesia is 59.2 in 2021. This score is lower than previous year and drop Indonesia rank from 62 to 69 out of 113 countries. This index employed four dimension that is called (1) availability; (2) affordability; (3) quality and safety; and (4) natural resources and resilience [1]. Food price is relatively affordable with sufficient food stock compare to other countries. However, infrastructure of food crops in Indonesia is below the average of global standard, in particular for nutrition and diverse healthy food, which have low scores. Moreover, natural resources management is insecure without strong government policy, and often suffer from the negative impact of climate change, extreme weather and environment degradation [1].

In 2021 measurements, GFIS introduced more than 20 questions in the country self-assessment to measure the efficacy of food safety mechanism. Based on the survey result, Indonesia needs a further assessment to obtain better food control system. Such assessment on the national standard on food security, legislation guidelines, laboratory capacity and tracing for food plans need to be improved. The government has taken some actions like developed food estate program. This program is intended to take benefit of commodity boom such as palm oil and rubber [2]. However, the fundamental issue to boost productivity in agriculture sector could not be solved by this policy. The fluctuation of food price and the less opportunity of land tenure by farmers has caused farmers difficulties to enhance productivity and meet the consumer demand for food.

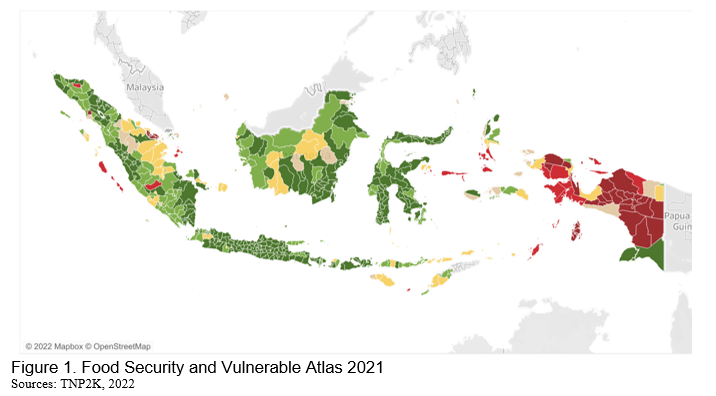

In this regard, the possibility of food insecurity may fall in the region with lack of vulnerable to get access and produce food. The Food Security and Vulnerability Atlas (FVSA) has been created by the World Food Program to help government in prioritizing resources to address crucial issues on food security in the Province and Regency/City [3]. The map below indicates the food security index of 514 districts in 2021. The result shows that 70 district in the five provinces namely, Maluku, North Maluku, East Nusa Tenggara, Papua and West Papua remained vulnerable to food insecurity (red color) [4].

Indonesia needs a comprehensive national food system which have a holistic agenda that serve all parties in the national food plans. Harmonizing the downstream to up stream of planning from each sector is challenging when each sector has its own planning and actions. Agriculture sector as a downstream level for instance, has long list of homework to be solved. First, the existing Food Act is not including women and marginalized groups have not been included. Second, genetic food resources have not been farmers’ common property; Organic farming is less common because it is hampered by certification aspect and the high-cost investment during the first three years; The determination of sustainable farm land and tenurial aspects (especially access to farm land) for the community has still not been fully guaranteed. Third, there is no food distribution mechanism from indigenous peoples to ‘conventional’ food markets; There have tendency that many local food (carbohydrate) sources, such as sorghum, millet, barley, and tubers been ignored. Fourth, the role of private sectors in food practices in Indonesia has been still low due to no clear mechanism for their participation. Fifth, the disparity between domestic rice price and of other countries indicates that the production of rice in Indonesia has still been inefficient, and such condition has pushed the practice of importing rice [5, 6, 7].

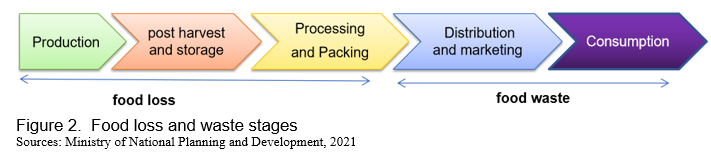

Moreover, one third of food production for human consumption is lost or wasted between the harvesting process and the consumption process (figure 2). It is predicted that food loss and waste (FLW) generation in Indonesia in 2000 - 2019 reached 23–48 million tons/year, or equivalent to 115–184 kg/capita/year. Food loss tend to decrease from 61% to 45% in the last 20 years. In contrast, the percentage of food waste shows increasing by 44% on average for the period 2000 - 2019 [8]. The largest critical loss of FLW generation is at the consumption stage, with food waste generation of 5–19 million tons/year. The largest contributor for FLW generation is crop sector, precisely rice and cereals, totaling 12-21 million tons/year. Further, the most inefficient type of food is the horticulture sector such as vegetables and fruit. The lost reaches 62.8% of the total domestic supply of vegetables in Indonesia. This figure put Indonesia as the world’s second largest food waster [9], while more than two million children suffer from malnutrition [10].

The potential economic loss of FLW generation, food poisoning and refusal of food export are also well calculated. The cost consists of direct health and non-health care cost and indirect non-health care cost. The overuse of some pesticides can cause several types of food poisoning bacteria and increase the risk of diarrhoea. The annual cases of diarrhoea due to food poisoning in Indonesia range from 4,157 to 9,170 cases/100,000 inhabitants, with an estimated loss of US$4.76–US$16.75 billion [11]. Further, the history of pesticides exposure probably could put pregnant women at risks to have stunted children [12,13]. The negative impact of stunting for future generations is well documented. The effect of stunting or malnutrition in the first 1,000 days of life, impairs brain development. In the long-term stunted children suffer from learning disabilities and are more likely to have lower capability to produce a high productivity [14].

Therefore, to address those issues, government has paying serious attention and strengthening regulation. The sustainable food system then believe could minimize environmental degradation and improve public health. By supporting a good food control system, the exposure of hazardous substance and malnutrition can be reduced. Protection against risk and strengthening institutional are important to be considered in assessing the food control system.

In this regard, implementing Penta helix approach to adopt circular economy and low carbon development concept in the framework of sustainable food system is considered in reinventing efficient sources and effective program in the agriculture system. Circular economy in the agri-food industry gives benefits for rural communities in reducing environmental impact [6], providing raw materials, combat climate change [14], regenerating the natural system [6, 14], increasing competitiveness, fostering innovation and economic growth [15].

This study explores reinventing circular agriculture in supporting healthy diets for all Indonesian. Circular agriculture approaches introduced new technologies and farming systems, which support food system particularly in reducing food loss and food waste. Regarding the food system, circular economy implies reducing the amount of waste generated in the food system, reuse of food, utilization of by products and waste, and nutrient recycling.

SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEM

A sustainable food system is defined as a dynamic process that supports food and nutrition security for future generation [16]. It can be guaranteed by the achievement of food and nutrition security in the current time. Three dimensions -economic, environment and social- are including at every stage of food system. From agriculture point of views, food system is climate-smart and should reducing global emission related to land use changes. Transformation of certain food particularly consumption of cereal, vegetables and fruit should consider balance nutrition. The calories and micro nutrition intake with appropriate composition can help balance diets as well as food and nutrition security [17].

In the downstream, the productive systems in agriculture are relying on diversifying farming practices. In some cases, agricultural diversification practices may increase output and make production more efficient [6]. To some degree, however, these practices may cause adverse effects on household welfare and the environment. The overuse of pesticides for instance, may cause health problems and damage the nutritional status of children. In the long-term, these environment-unfriendly practices potentially reduce soil quality and could have undesirable climate-change effects [7].

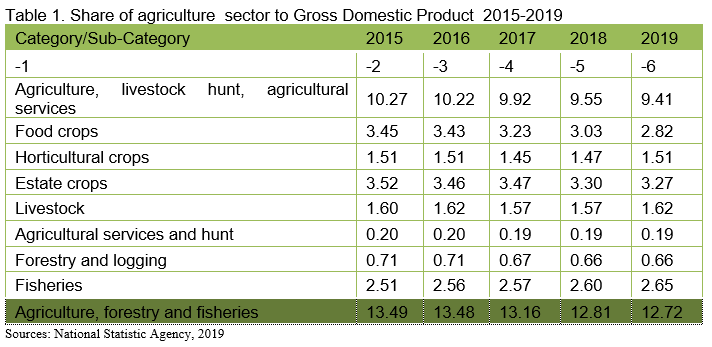

Table 1 shows the share of agriculture in several sub categories to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) based on market prices from 2015 to 2019. Although the share of the agriculture sector has decreased, the growth of agriculture has slightly increased particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. Food crops and estate crops are the leading sub-sector, which contribute to national GDP stable at 3%. Agricultural sector (13.2%) has the second largest contribution to 2021’s national GDP after the manufacturing sector (19.25%) [18]. In line with this, by applying circular economy, it is predicted that in 2030, circular economy contributes to additional 2.3 - 3 percent. However, it should be noted that the adoption of a circular economy could lead to reduced consumer demand, and lead to slower growth than business as usual [5, 15]. In terms of growth, agriculture remains the lowest compare to other sectors. Agriculture grew 1.25% in 2021, while trade and repair services grew more than 4%. Agriculture sector needs to grow close to 7% to be a leading sector in developing country, and this growth is expected sustain for the long period in the future [19].

Healthy diets from sustainable food system

Dietary risks increased by 18.7% between 2007 and 2017. Malnutrition's Triple Burden (calorie and protein deficiency, micronutrient deficiency, and an abundance of calories) have also haunted Indonesians citizens [20] . Global Hunger Index ranked first on a global scale. Indonesia is ranked 73rd out of 119 countries observed [1]. The burden of malnutrition represents a violation of the human right to food and continues to drive health and social inequalities. Diversifying diets with high quality, safe, and nutritious foods can help reduce micronutrient deficiencies by providing a rich source of nutrients all year [21].

National food systems, on the other hand, provide less diverse food. This is reflected in monotonous diets based on a few staple crops, while access to nutrient-rich sources of food, such as animal source foods, fruits and vegetables is a challenge. Moreover, unsynchronized food causes the paradox of system of planning. There is no interconnection in the planning, between upstream and downstream as well as the implementation of food practices in Indonesia.

Healthy diets from a sustainable food system are diets that are health-promoting and disease-preventing; diets that are available, affordable, accessible, and appealing to all, diets that are produced and distributed using methods that ensure decent work and sustain the planet, soil, water, and biodiversity [22]. Diet evolves over time, being influenced by many social and economic factors that interact in a complex manner to shape individual dietary patterns. These factors include income, food prices (which will affect the availability and affordability of healthy foods), individual preferences and beliefs, cultural traditions, and geographical and environmental aspects (including climate change). Therefore, promoting a healthy food environment – including food systems that promote a diversified, balanced and healthy diet – requires the involvement of multiple sectors and stakeholders, including government, and the public and private sectors [20].

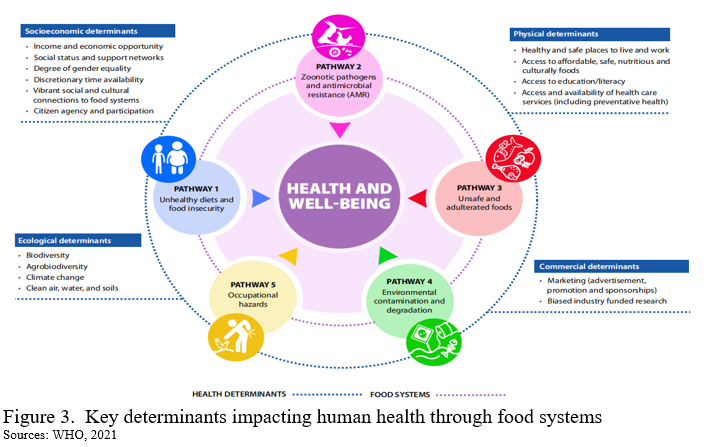

Figure 4 shows five pathways on the food system which can have a negative impact on health and well-being. This is a guideline from World Health Organization to manage food system in delivering better health diets [20]. The first pathway includes aspects of the food system that lead to unhealthy diets or food insecurity and thus contribute to malnutrition in all its forms. Animal pathogens and antibiotic resistance is the second pathways. This includes wildlife being caught in the food supply chains and the use of antibiotics leading to zoonotic diseases and antibiotic resistance, leading to infectious diseases and diseases not transmissible in humans.

Dangerous and adulterated food is the following pathway. This pathways in the food system are the cause of various diseases (e.g., micronutrient deficiencies, stunting, emaciation, infectious and non-communicable diseases and mental illness) when food and Drinking water contains infectious or toxic hazards, microbial pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses and parasites, or chemical residues, contaminants or biological toxins. These contaminants can appear in unsafe food supply chains or in unhealthy environments or as a result of unsafe behaviors.

The environment is polluted and degraded pathway includes environmental pollution through the use in the food supply chain and the food environment with fertilizers, manures, products containing heavy metals, endocrine disrupting chemicals or stimulants. growth hormone, can cause different conditions, such as mental illness and other diseases -infectious diseases and infectious diseases. This includes how food production, the food environment and the behavior of citizens degrade the environment by emitting air pollutants, greenhouse gases and microplastics, affecting health and well-being.

Occupational risk is a pathway in the food system which can cause many impacts on the physical and mental health for farmers, fishermen, agricultural workers and those working in the retail sector such as processing and food chains. Impacts include stress from heat and cold, trauma, exposure to chemicals through the use of pesticides, fertilizers and insecticides, biological hazards such as snake bites, infectious diseases and parasites, zoonotic diseases, ergonomic hazards and psycho-social risks leading to stress and mental illness, including suicide.

Transforming food system to deliver health should change the narrative and decision makers on food system. The policy support should govern systemic changes for better health by implementing three pillars; mainstreaming the concept of healthy, sustainable diets; democratic, transparent, accountable governance frameworks; and accessible, credible interdisciplinary research.

Indonesia sustainable food system

Sustainable food system, including ensuring inclusive access, sustainable production and consumption, as well as minimizing food loss and waste is a priority. In the Sustainable Development Goal 2, food becomes important agenda to end hunger, to achieve food security and to improve nutrition as well as to promote sustainable agriculture.

Currently, the farming practices which is supply-oriented rather than demand-oriented is one of the indicator that food system in Indonesia is less sustainable [4, 11]. The use of chemical instead of promoting organic farming due to government subsidized fertilizers is another indicator for less sustainable agriculture. Moreover, the national food logistical and distribution are also supporting such practices.

Indonesia has been most focusing food self-sufficiency on rice, corn and soybean and the ministry of agriculture has push exported for fruit and horticulture product. The paradox between the abundance of food quantity, non-communicable diseases associated with dietary risk is even becoming the highest risk factor for mortality and disability in Indonesia. Therefore, Indonesia needs to change the conventional paradigm on food system to be able to reach sustainable food system.

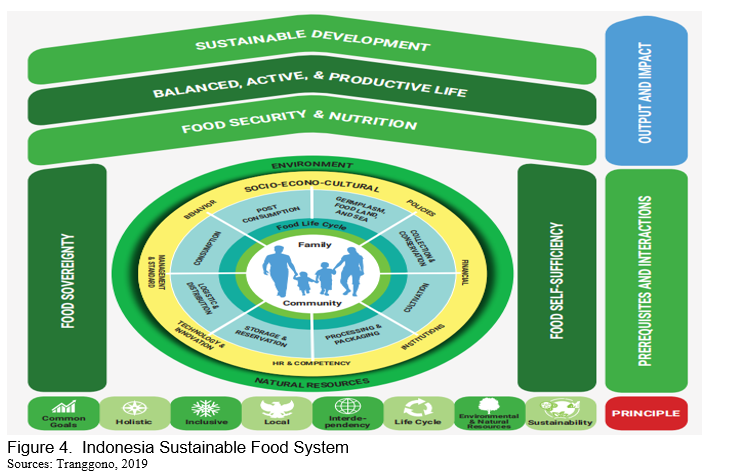

The sustainable food system or it is called Pangan Bijak Nusantara (Wise Foodways of the Archipelago) consist of eight principles. This mandatory principle includes holistic, inclusive, local, life-cycle, interdependence, environmental and natural resources system and sustainability [16]. Figure 4 displays the concept of Indonesia Sustainability Food System (ISFS), which is based on family as the smallest system in the community to implement it. Families are the cores and spearheads in developing healthy, diverse and responsible food consumption pattern. The interaction among food actors and stakeholders across the food life cycle is the common ground of sustainable food system. The production and consumption that considering social, economic and cultural factors should be implemented consistently sustainable [20].

Preserving environment and natural resources are also concerned in the sustainable food system. It confirms that the system must work within the potential limits of the environment and natural resources. Food autonomy component is associated with the right to food selection, whereas the food sovereignty component is related with a nation’s capacity to provide by itself with all or a certain amount of food. Both components are the prerequisites for the realization of sustainable food system [16, 23].

Food security and nutrition are essentially the outputs of a sustainable food system. Individuals who are active, healthy, and productive are the system's outcomes. Indonesian community must choose diverse, healthy, and sustainable food as the country's food consumption pattern. The nutrition security from the availability of safe food at any time in sufficient quantity is the goal of the system. A clean and healthy lifestyle are the key point to achieved by all actors and stakeholders.

ISFS covers all stages of the food life cycle, not just production. The state must play an active role in the food system, particularly in ensuring food availability and price stability as mandated by the Food Act [16]. To ensure the success of ISFS, the Indonesian government must devise an appropriate incentive and disincentive system. Furthermore, all actors and stakeholders must be accommodated and guaranteed to participate actively. In short, ISFS must be participatory by definition. It is believed that the holistic achievement of a sustainable food system will contribute to meet the current needs for healthy and diverse food without risk future generations' ability to meet their own needs.

INTERVENTION, INNOVATION AND POLICY CONSIDERATION

Reinventing circular agriculture

In the view of agricultural economics, the circular economy has been widely adopted in the form of a smallholder integrated farming system, but it lacks improvement [6]. Integrated farming systems have been proven to combine food crops, horticultural crops and raising cattle into one cycle of production. At this point, farmers are gaining the circular economy routine [7]. Further, the concept of circular economy is in line with the idea of sustainable agriculture [7]. In this regard, sustainable farming is developed by less external input, and long-lasting participation of farm households. The improvement of organic farming, biological farming, bio-circular agriculture, and regenerative agriculture are the direction of a sustainable farming system [6, 25].

Moreover, circular agriculture is a part of the sustainable agriculture concept. By definition, this terminology includes any production and consumption model, which involves sharing, renting, reusing, repairing, renovating and recycling existing materials and products for as long as possible [26] and reducing to the minimum of waste” [15], offering a better alternative to the current model of economic development, the “take, do and dispose of” model [16] with a view to economic, environmental, and social sustainability [5].

In short, the differences between Circular Business Models (CBMs) and Linear Business Models (LBMs) relate to three aspects that is ownership, responsibility, and budget structure [27]. The ownership of a product in a CBMs, including its waste, remains with the seller. Business responsibility in CBMs focuses on environmental, social, and financial value propositions. The adoption of CBMs leads to differences in budget structure which include both cost and revenue streams. Organic waste is one of the core wastes in agriculture sector that preferably needs biological treatment. The green revolution effect causes farmers to use pesticides, herbicides which are harmful for human health. The biological pest control is then a win for the environment [5]. In the case of Indonesia, new technologies and innovation like the use of drone spray or related internet of things to operate agricultural equipment are introduced lately. Indonesian smallholders’ farmers should take the opportunity to be able to use drone technology, but the cost is not affordable for poor farmers. If farmers are part of a large farmers group or a cooperative, on that level, they would be able to lease a drone. New business cases need to be developed to reach the majority of farmers in Indonesia. The Indonesian government has to make it easier, in relation to policies and regulations, to make these innovations available and in reach of farmers [25].

Indonesia government has implemented a national project named Nucleus Estate Smallholders (NES) over 30 years. However, maintaining continuity and sustainability of the program is hardest challenge. The smallholder farmers remain left behind and less acknowledgement in the form of patron-client relation with the government and companies [6]. Therefore, to enhance the performance of this NES program, evaluation and redesigning of the NES program is expected to find an improved outcome for better business partnership among the stakeholders. Several cases have applied the concept of circular agriculture by fostering partnership between farmer and company as displayed in Table 2. Most of the company activities follow the guidance of sustainability concepts that is deploying a triple bottom line i.e. planet, people and profit as suggested by John Elkington (1994). Further, NGO and CSO have participated in and take benefit from circular agriculture activities.

Due to these effects, the Indonesian private sector has become more aware of the circularity aspect in their business and is showing its commitment to adopt circular business models. A survey of 57 Indonesian firms conducted as part of this research highlighted that the vast majority (almost 80 percent) have a strong willingness to engage in the development of a national circular economy strategy [15].

Table 2. Some initiatives to implement a circular economy in agricultural sectors.

|

No

|

Company

|

Partner

|

Program

|

Business Model

|

Innovation

|

|

1

|

Multi Bintang Indonesia.

|

Local cooperation (CV langgang Dumadi and KUD Budi Raharjo)

|

“Brewing a better world”

|

-Circular supply chain

-Product life cycle extension

|

- Using rice husks as renewable energy sources in biomass plant

- Zero waste to landfill

- Returnable bottle system

|

|

2

|

BIOS Agrotekno

|

No local partner as farmers are too afraid to adopt the new system.

|

Precision irrigation

|

Sharing platform

|

Automatic irrigation using IOTs is called ENCOMOTION.

|

|

3

|

Sarihusada (Danone Indonesia)

|

Lembaga Pengembangan Teknologi Pedesaan (Rural Technology Development Institute) in Yogyakarta and Central Java

|

Regenerative agricultural practices

|

Resources recovery

|

Built large-scale bio-digester for communal sheds in Merapi project.

|

|

4

|

Re>Pal

|

Farmer in East Java

|

Zero waste pallets

|

Resources recovery

|

zero waste pallets are made from 100% waste plastic using Re>Pal’s unique Thermo Fusion technology process.

|

|

5

|

PT Bukit Asam

|

Farmers at Pagar Dewa Village, Muara Enim Regency, South Sumatera

|

Industrial Central of Bukit Asam (Sentral Industri Bukit Asam) Program

|

Resources Recovery

|

Changing waste to energy (Solar Cell) as an engine for operating rice mill units, rice polisher, etc.

|

|

6

|

Ministry of Marines and Fisheries working together with Republic of France (IRD/GDA/CRIA)

|

Fishers at Singkut village, Jambi

|

Maggot Bio-conversion for fish meal replacement

|

Resource recovery

|

Fish meal replacement: Pellet for red gurame and Vanname Shrimps

|

Sources: various publications, 2022

In the "Brewing" program, producing biomass facilities use rice husks, sourced from local rice mills and collectors, to produce thermal energy. The burning of rice husks heats the boilers used for brewing and other business activities in the company's production process. Rice husks were previously perceived as waste by farmers. Using rice husks as an energy source hand over for it is usually free to take depending on the time of a year, but there may be transport costs involved. For example, in April 2020, 116 tons of rice husks were used, leaving out only 23.2 tons of rice husk ash. The rice husk ash was not wasted, as it was used in other ways. Ash with high silica content can be used as an ingredient in construction, brick making, poultry bedding, and powerful organic fertilizers, and through BECIS Bioenergy's CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) initiative, rice husk ash is given to community for free. Communities in Trawas, Sudimoro, Mojoranu, and also Sampangagung used this ash for composting (63.8 tons), brick making (17.6 tons) and construction material (6.6 tons). In addition, the circularity of this waste can be produced as spent grains and spent yeast which is semi liquid material, difficult to transport. These high nutrients for farming were sold to local cooperation such as CV Langgeng Dumadi, KUD Tritunggal, and KUD Budi Raharjo. They re-sell spent grains to local farmers. While, other partnership with dairy company PT Greenfields who uses the spent grains to feed their cows. PT Maqpro Biotech Indonesia is another partner who buys only our spent yeast, processing it to make feed for fish and shrimps [26].

In addition, leading consumer goods companies such as Unilever, Nestle, Indofood, Coca-Cola, Danone and Tetra Pak have established PRAISE, an organization that aims to accelerate the adoption of a circular economy in the private sector in Indonesia [25]. The company goal is to reduce the company's emissions intensity by 50% by 2030 and to eventually achieve net-zero emissions across Danone's entire emissions footprint. In relation to circular agriculture, Danone (Sari Husada) has established e large-scale bio-digester for communal sheds in ‘Merapi Project’, located in Umbulharjo, Cangkringan, Sleman, Yogyakarta [26]. This project has objective to increase farmer awareness about how to manage dairy cow dung as well as help them produce high quality feed for their dairy cows. Forage that is of high quality is needed to increase the total solid content in fresh milk, which can give a farmer a better price for his milk. Total solid fertilizer potential produced from this facility is around 3,000 Kg per month. A small amount of organic fertilizer is used by farmers to their own grass land, and the rest they sell for getting additional income.

In this regard, the circular economy has been mutually providing benefits to farmers. However, to improved integrated farming systems as a recycle economic activity has not been adequately captured by introducing new farming systems approach. To apply CBMs may incur extra costs to recycle agricultural waste, at least cost to transport the recycle waste to product or energy from the company stations to farmer land or home. The absence of social pressures and the presence of practical constraints likely explains why the respondents have not implemented relevant business strategies. For example, having a good partner as the appropriate early adopter is a challenge for companies to implement 6R concepts (Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Remanufacturing, Recycle, and Recover).

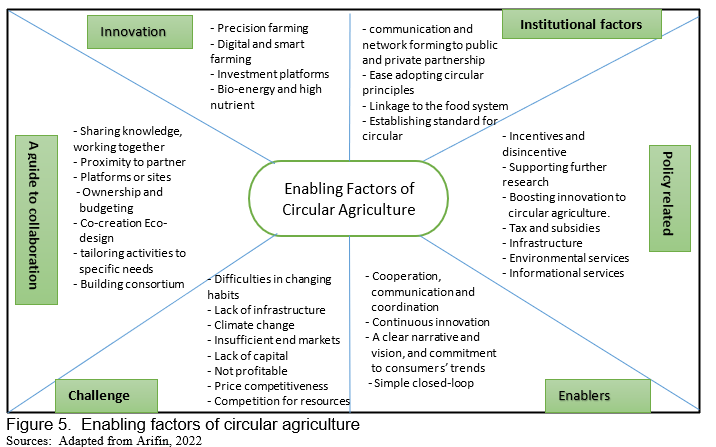

Enabling factor of circular agriculture

Business model in circular agriculture differs from classical business model. Maintaining good financial health, efficient use of resources and achieving long-term viability of the firm are the principle aims of this business model. It emphasizes the collaborative character, which require cooperation, communication and coordination with a wide range of stakeholders.

Figure 5 and Table 2 explain the barriers to implement circular agriculture practices. The critical success or barriers to implement circular agriculture are varied across firms, communities and nations. The complexity of sustainable food system is also reflected in this business model. Based on the literature reviews, there are some external and internal challenges that include lack of consumer acceptance of waste-based products, a missing willingness to invest in unsure and risky environmental innovations by businesses, a missing industry framework to seize and communicate sustainability to different stakeholders, climate change that causes investment fail, less profit compares to business as usual, price competitiveness with product without recycling process. Furthermore, Rizos et al. (2016) uncovered barriers for circular agriculture, including a lack of support from the supply and demand network, insufficient capital for investment, and also sometimes a lack of government support, of technical know-how or administrative burdens. Internal barriers were a lack of knowledge and technology, organizational and financial structures, and external barriers were related to the supply chain, markets and institutions (e.g., policies, standards) [28].

Meanwhile, the sequential factors for translating circular agriculture into a new business model are collaboration, continuous innovation, a clear history and vision, profitability, commitment to sustainability and external events such as consumers’ trends or food crises. An important way to promote circular systems that is to improve information connections across the food system from consumers to producers. Experience with the positive impact of organic certification and labeling programs on the development of the organic food industry demonstrates the potential of such policies to translate consumer demand for producers through positive price signals [29].

Setting standards for circular and sustainable food production practices and related product certification and labeling would provide a market-based mechanism to reward private investments in more circular and sustainable technologies and their adoption by farmers [25]. Hence, the development of more efficient food markets also requires public and private investments in better data and information systems that can credibly convey information on farm production practices across the food system to consumers. In doing so, having sustainable technology innovation center that is completely integrated into the production chain will benefit companies to sustain their business [28]. Building perspectives on the role of waste management service providers are positive as it can be tool to help them to be more effectively practicing good handling food management in their supply chain process. To convince farmers and other stakeholders to participate in this business, therefore, persuasive communication can be effective by helping farmer’s stakeholders to see the financial feasibility of adopting a circular economy model.

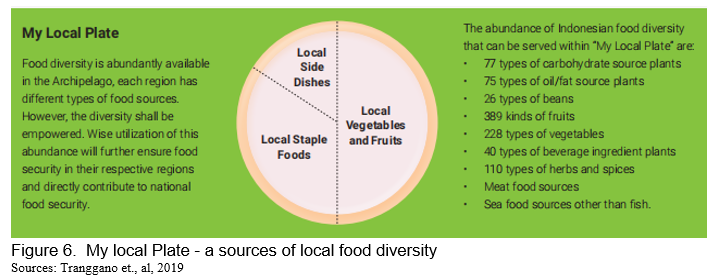

Diverse healthy food

Besides promoting circular agriculture, food diversity is also part of the strategy in a sustainable food system. The “Isi Piringku” (My Plate) initiative, a government program on healthy diets designed to support food diversity. Food diversity has been marginalized while at the same time dismissing local food potentials and its various wisdom that have been proven as high resilience [16, 23].

Indonesia enriches with local agri-food that provide nutrition and health among low-income urban and rural consumers. Agri-food value chains serve as a vehicle to connect producers who are often in rural areas, with consumers in peri-urban and urban areas. “My Plate” can be suited with food resources available in each region. Diversity of food across region can be served in the “my Plate” and “My local Plate” menu. Each region may differ in food type in term of its carbohydrate, protein, vegetables, fruits and even seasoning sources. However, the proportion of “My plate” shall include a half portion of vegetable and fruits, and a half another is staple food and side dishes [16].

A healthy diverse diet must be introduced since early age and accepted as habit or lifestyle. Indonesian families will therefore be the spearheads in developing healthy diverse eating habit and character. However, the paradox between abundance vegetables and fruit production and malnutrition of those food due to food loss or more export oriented, becomes paralyzed since the scarcity of food suppliers and lack of management in logistic and distribution.

The raising of awareness, understanding, and competency of the Indonesian families regarding “My Local Plate” shall be developed in a systematic and sustainable manner. In this context, the concept of “my plate” has to be adopted at all level of school to provide healthy diets at all level education. School canteens and process food may introduce the local diversity of food from each region and promote circular activities to reduce food waste. Another initiative to train children on the variety of local food is by introducing urban farming that is called Kebun sekolah (School Garden). The following program can be set up from this activity such as “Panen Beragam Sekolah” (School Diverse Harvest Day), and “Pesta Pangan Lokal” (Local Food Festival) as regular agenda [16, 23].

CONCLUSION

Circular economy has gained momentum in Indonesia’s economy during the corona virus pandemic. The linear approach “Take-Make-Waste” failed in maintaining sustainable world’s food stocks, thus promoting the circular economy approach “Make-Consume-Enrich” creates extended producer responsibility (EPR) to produce recycled products. This is a strategy to deploy multiple circular economies at local, regional, and global scale in different industrial sectors.

Circular agriculture is one of an alternative way in response to global issues on resource depletion that causes food insecurity. In the Indonesia sustainable food system framework, promoting circular agriculture is expected to reduce the unhealthy diets and malnutrition issues. Indonesia needs to solve many obstacles that improve agriculture productivity to end hunger as one of the targets in Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, increasing the performance of global food security index particularly in Eastern part of Indonesia shall be supported by shifting paradigm in the Indonesia food system.

The absence of holistic and inclusive food system seems to be the cause of food value chain series from upstream to downstream is not well managed. This study explores the relation between sustainable food system and reinventing circular agriculture to enhance healthy diets program to all Indonesian families. Some conclusion from this study emphasizes that enabling factors to tackle barriers in promoting circular agriculture as part of sustainable food systems are including these factors: (1) technical and logistic;, (2) economic, financial and marketing; (3) organizational and spatial; (4) institutional and legal; and (5) environmental, social and cultural. The innovative conversion with continuity and sustainability program needs joint investment between private and public sectors to pursue research and development. Regulation and policy action are also needed in order to provide such conducive climate for price competitiveness for bio-based products, space availability, subsidies, agricultural waste management regulations, local stakeholder involvement and acceptance of bio-based production processes.

Public awareness on healthy diets shall be encouraged by promoting education about sustainable food system particularly balance diets for younger age at elementary and secondary school. The curricula at all stages shall include promoting the diversity of local food by introducing organic farming practices, urban farming practicing and various type of food from many regions in Indonesia. Importantly, the strengthening governance to food and nutrition security should be in the front to support food system, which is more complex and need high level of coordination, communication and cooperation among a wide range of stakeholders.

1. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, Global Food Security Index: Measuring Food Security and the Impact of Resource Risks. 2021, The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, London, UK.

2. Suhartini, S., et al., Biorefining of oil palm empty fruit bunches for bioethanol and xylitol production in Indonesia: A review. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews, 2022. 154: p. 111817.

3. World Food Program, The Food Security and Vulnerability Atlas of Indonesia. 2021, World Food Program: Jakarta.

4. TNP2K, 2022, Pemantauan kondisi ketahanan pangan berdasarkan ketersediaan, akses, dan pemanfaatan bahan pangan, diunduh dari https://dashboard.stunting.go.id/ketahanan-dan-kerentanan-pangan/

5. Nattassha, R., et al., Understanding circular economy implementation in the agri-food supply chain: the case of an Indonesian organic fertiliser producer. Agriculture & food security, 2020. 9: p. 1.

6. Pasaribu, S.M., Factors Affecting Circular Economy Promotion in Indonesia: The Revival of Agribusiness Partnership in International Conference on Environment and Circular Economy. 2004: Nankai University, Tianjin.

7. Ilham, N. and S. K.D., Sistem Usahatani Terpadu dalam Menunjang Pembangunan Pertanian Berkelanjutan. Kasus Kabupaten Magetan, Jawa Timur in Dinamika Inovasi Sosial Ekonomi dan Kelembagaan Pertanian, A.R. I.W.Rusastra, et al., Editors. 1999, Pusat Penelitian Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian, Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pertanian, Departemen Pertanian.: Bogor.

8. BAPPENAS 2021 Laporan Kajian Food Loss and Waste di Indonesia dalam Rangka Mendukung Ekonomi Sirkular dan Pembangunan Rendah Karbon (Jakarta: BAPPENAS)

9. Bisara, D., Indonesia Second Largest Food Waster in Jakarta Globe. 2017, JAKARTAGLOBE: Jakarta.

10. Karana, K.P., Indonesia: Number of malnourished children could increase sharply due to COVID-19 unless swift action is taken. 2020, UNICEF Indonesia: Jakarta

11. Alim, K. Y., Rosidi, A., & Suhartono, S. (2018). Riwayat Paparan Pestisida Sebagai Faktor Risiko Stunting Pada Anak Usia 2-5 Tahun Di Daerah Pertanian. Gizi Indonesia, 41(2), 77-84.

12. Apriluana, G., & Fikawati, S. (2018). Analisis faktor-faktor risiko terhadap kejadian stunting pada balita (0-59 bulan) di negara berkembang dan asia tenggara. Media Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan, 28(4), 247-256.

13. Belinda Tanoto, Stunting prevention in Indonesia: Strategy, will and collective effort, in The Jakarta Post. 2020, PT Bina Media Tenggara: Jakarta.

14 Tansy Robertson Five benefits of a circular economy for food. Circular Economy, 2021.

15. Kementerian PPN/Bappenas, Embassy of Denmark Jakarta, and United Nation Development Program, Summary for Policymakers: The Economic, Social, and Environmental Benefits of a Circular Economy in Indonesia. 2021, Minister of National Planning and Development Indonesia/Bappenas: Jakarta

16. Tranggono Ario, Chandra Wirman, Any Sulistiowati and Teten Avianto, 2019, Strategy Paper Indonesia Sustainable Food System, Switchasia; Kementerian PPN/Bappenas; Pangan Bijak Nusantara; European Union; WWF; Hivos; NTFP Indonesia; ASPPUK, Jakarta:

17. Van Hoye, I. (2016). The European Innovation Partnership “Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability”-networking tools and ‘green economy’activities.

18. Statistic Indonesia, Official Statistics News in Indonesia Economic Growth Quarter IV - 2021. 2022, Badan Pusat Statistik: Jakarta.

19. Umi K. Yaumidin, Essays On Sustainable Agriculture In Indonesia, in the Economic Department. 2021, Australian National University: Canberra.

20. World Health Organization. (2021). Food systems delivering better health: executive summary.

21. Martianto, D. (2010). Food and nutrition security situation in Indonesia and its implication for the development of food, agriculture and nutrition education and research at Bogor Agricultural University. Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture, 5(1), 64-81.

22. Drewnowski, A., Finley, J., Hess, J. M., Ingram, J., Miller, G., & Peters, C. (2020). Toward healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4(6), nzaa083.

23. Arif, S., Isdijoso, W., Fatah, A. R., & Tamyis, A. R. (2020). Strategic Review of Food Security and Nutrition in Indonesia: 2019-2020 Update. Jakarta: SMERU Research Institute.

25. Santeramo, F.G., Circular and green economy: the state-of-the-art. Heliyon, 2022. 8(4): p. e09297-e09297.

26. Rossum, T.v., Circular Economy in The Indonesian Agricultural Sector: Case Studies from the Field for a Circular vision. 2020, Agrodite: Jakarta.

27. Auwalin, I., et al., Applying the Pro-Circular change model to restaurant and retail businesses’ preferences for circular economy: evidence from Indonesia. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 2022. 18: p. 97-113.

28. Rizos, V., Behrens, A., Van der Gaast, W., Hofman, E., Ioannou, A., Kafyeke, T., ... & Topi, C. (2016). Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and enablers. Sustainability, 8(11), 1212.

29. Antikainen, M., & Valkokari, K. (2016). A framework for sustainable circular business model innovation. Technology Innovation Management Review, 6(7).

Reinventing Circular Agriculture, Sustainable Food System and Healthy Diets in Indonesia

ABSTRACT

The sustainable food system is dynamics process where the achievement of current food security will not hamper the capability of future generation to secure their food. The concept of healthy diets and circular economy approaches to reduce food loss and waste is addressed in the sustainable food system framework. Relate to this concept, circular agriculture is well known in Indonesia. It has been translated into sustainable and integrated farming system. Circular agriculture gives more benefits to farmers welfare than linear agriculture. Reinventing this concept by enhancing collaboration among agricultural stakeholders that is improving patron-client system between smallholder farmers and business is one of enablers factors in the transition of linear model business to circular model business. This study explores the relation between promoting eight principles of sustainable food system, encouraging Indonesian families to follow dietary plan, and reinventing circular agriculture. Circulating agricultural waste into new product or a source of energy could help unfortunate households to get decent livelihood and fulfilling nutritional intake for children. Hence, governance of food security by adopting circular agriculture to manage food loss and waste is simple action in the loop of complexity of sustainable food system. The holistic and inclusive approach of sustainable food system could reduce unhealthy diets across Indonesia families. The policy implementation to enabling these three aspects is not enough by launching regulation in taxes and subsidies, incentive and disincentive scheme, or other financial support system. The collaboration across farmer’s stakeholder in bio-conversion, research and development, and changes producer and consumer behaviors in the acceptance of bio-conversion product are also important. Early education on the important issues in promoting circular agriculture, healthy diets and food system at all stage level of education shall be prioritized in the government agenda.

Keywords: Circular Agriculture, Food Security, Healthy Diets.

INTRODUCTION

The overall score of Global Food Security Index (GPSI) for Indonesia is 59.2 in 2021. This score is lower than previous year and drop Indonesia rank from 62 to 69 out of 113 countries. This index employed four dimension that is called (1) availability; (2) affordability; (3) quality and safety; and (4) natural resources and resilience [1]. Food price is relatively affordable with sufficient food stock compare to other countries. However, infrastructure of food crops in Indonesia is below the average of global standard, in particular for nutrition and diverse healthy food, which have low scores. Moreover, natural resources management is insecure without strong government policy, and often suffer from the negative impact of climate change, extreme weather and environment degradation [1].

In 2021 measurements, GFIS introduced more than 20 questions in the country self-assessment to measure the efficacy of food safety mechanism. Based on the survey result, Indonesia needs a further assessment to obtain better food control system. Such assessment on the national standard on food security, legislation guidelines, laboratory capacity and tracing for food plans need to be improved. The government has taken some actions like developed food estate program. This program is intended to take benefit of commodity boom such as palm oil and rubber [2]. However, the fundamental issue to boost productivity in agriculture sector could not be solved by this policy. The fluctuation of food price and the less opportunity of land tenure by farmers has caused farmers difficulties to enhance productivity and meet the consumer demand for food.

In this regard, the possibility of food insecurity may fall in the region with lack of vulnerable to get access and produce food. The Food Security and Vulnerability Atlas (FVSA) has been created by the World Food Program to help government in prioritizing resources to address crucial issues on food security in the Province and Regency/City [3]. The map below indicates the food security index of 514 districts in 2021. The result shows that 70 district in the five provinces namely, Maluku, North Maluku, East Nusa Tenggara, Papua and West Papua remained vulnerable to food insecurity (red color) [4].

Indonesia needs a comprehensive national food system which have a holistic agenda that serve all parties in the national food plans. Harmonizing the downstream to up stream of planning from each sector is challenging when each sector has its own planning and actions. Agriculture sector as a downstream level for instance, has long list of homework to be solved. First, the existing Food Act is not including women and marginalized groups have not been included. Second, genetic food resources have not been farmers’ common property; Organic farming is less common because it is hampered by certification aspect and the high-cost investment during the first three years; The determination of sustainable farm land and tenurial aspects (especially access to farm land) for the community has still not been fully guaranteed. Third, there is no food distribution mechanism from indigenous peoples to ‘conventional’ food markets; There have tendency that many local food (carbohydrate) sources, such as sorghum, millet, barley, and tubers been ignored. Fourth, the role of private sectors in food practices in Indonesia has been still low due to no clear mechanism for their participation. Fifth, the disparity between domestic rice price and of other countries indicates that the production of rice in Indonesia has still been inefficient, and such condition has pushed the practice of importing rice [5, 6, 7].

Moreover, one third of food production for human consumption is lost or wasted between the harvesting process and the consumption process (figure 2). It is predicted that food loss and waste (FLW) generation in Indonesia in 2000 - 2019 reached 23–48 million tons/year, or equivalent to 115–184 kg/capita/year. Food loss tend to decrease from 61% to 45% in the last 20 years. In contrast, the percentage of food waste shows increasing by 44% on average for the period 2000 - 2019 [8]. The largest critical loss of FLW generation is at the consumption stage, with food waste generation of 5–19 million tons/year. The largest contributor for FLW generation is crop sector, precisely rice and cereals, totaling 12-21 million tons/year. Further, the most inefficient type of food is the horticulture sector such as vegetables and fruit. The lost reaches 62.8% of the total domestic supply of vegetables in Indonesia. This figure put Indonesia as the world’s second largest food waster [9], while more than two million children suffer from malnutrition [10].

The potential economic loss of FLW generation, food poisoning and refusal of food export are also well calculated. The cost consists of direct health and non-health care cost and indirect non-health care cost. The overuse of some pesticides can cause several types of food poisoning bacteria and increase the risk of diarrhoea. The annual cases of diarrhoea due to food poisoning in Indonesia range from 4,157 to 9,170 cases/100,000 inhabitants, with an estimated loss of US$4.76–US$16.75 billion [11]. Further, the history of pesticides exposure probably could put pregnant women at risks to have stunted children [12,13]. The negative impact of stunting for future generations is well documented. The effect of stunting or malnutrition in the first 1,000 days of life, impairs brain development. In the long-term stunted children suffer from learning disabilities and are more likely to have lower capability to produce a high productivity [14].

Therefore, to address those issues, government has paying serious attention and strengthening regulation. The sustainable food system then believe could minimize environmental degradation and improve public health. By supporting a good food control system, the exposure of hazardous substance and malnutrition can be reduced. Protection against risk and strengthening institutional are important to be considered in assessing the food control system.

In this regard, implementing Penta helix approach to adopt circular economy and low carbon development concept in the framework of sustainable food system is considered in reinventing efficient sources and effective program in the agriculture system. Circular economy in the agri-food industry gives benefits for rural communities in reducing environmental impact [6], providing raw materials, combat climate change [14], regenerating the natural system [6, 14], increasing competitiveness, fostering innovation and economic growth [15].

This study explores reinventing circular agriculture in supporting healthy diets for all Indonesian. Circular agriculture approaches introduced new technologies and farming systems, which support food system particularly in reducing food loss and food waste. Regarding the food system, circular economy implies reducing the amount of waste generated in the food system, reuse of food, utilization of by products and waste, and nutrient recycling.

SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEM

A sustainable food system is defined as a dynamic process that supports food and nutrition security for future generation [16]. It can be guaranteed by the achievement of food and nutrition security in the current time. Three dimensions -economic, environment and social- are including at every stage of food system. From agriculture point of views, food system is climate-smart and should reducing global emission related to land use changes. Transformation of certain food particularly consumption of cereal, vegetables and fruit should consider balance nutrition. The calories and micro nutrition intake with appropriate composition can help balance diets as well as food and nutrition security [17].

In the downstream, the productive systems in agriculture are relying on diversifying farming practices. In some cases, agricultural diversification practices may increase output and make production more efficient [6]. To some degree, however, these practices may cause adverse effects on household welfare and the environment. The overuse of pesticides for instance, may cause health problems and damage the nutritional status of children. In the long-term, these environment-unfriendly practices potentially reduce soil quality and could have undesirable climate-change effects [7].

Table 1 shows the share of agriculture in several sub categories to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) based on market prices from 2015 to 2019. Although the share of the agriculture sector has decreased, the growth of agriculture has slightly increased particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. Food crops and estate crops are the leading sub-sector, which contribute to national GDP stable at 3%. Agricultural sector (13.2%) has the second largest contribution to 2021’s national GDP after the manufacturing sector (19.25%) [18]. In line with this, by applying circular economy, it is predicted that in 2030, circular economy contributes to additional 2.3 - 3 percent. However, it should be noted that the adoption of a circular economy could lead to reduced consumer demand, and lead to slower growth than business as usual [5, 15]. In terms of growth, agriculture remains the lowest compare to other sectors. Agriculture grew 1.25% in 2021, while trade and repair services grew more than 4%. Agriculture sector needs to grow close to 7% to be a leading sector in developing country, and this growth is expected sustain for the long period in the future [19].

Healthy diets from sustainable food system

Dietary risks increased by 18.7% between 2007 and 2017. Malnutrition's Triple Burden (calorie and protein deficiency, micronutrient deficiency, and an abundance of calories) have also haunted Indonesians citizens [20] . Global Hunger Index ranked first on a global scale. Indonesia is ranked 73rd out of 119 countries observed [1]. The burden of malnutrition represents a violation of the human right to food and continues to drive health and social inequalities. Diversifying diets with high quality, safe, and nutritious foods can help reduce micronutrient deficiencies by providing a rich source of nutrients all year [21].

National food systems, on the other hand, provide less diverse food. This is reflected in monotonous diets based on a few staple crops, while access to nutrient-rich sources of food, such as animal source foods, fruits and vegetables is a challenge. Moreover, unsynchronized food causes the paradox of system of planning. There is no interconnection in the planning, between upstream and downstream as well as the implementation of food practices in Indonesia.

Healthy diets from a sustainable food system are diets that are health-promoting and disease-preventing; diets that are available, affordable, accessible, and appealing to all, diets that are produced and distributed using methods that ensure decent work and sustain the planet, soil, water, and biodiversity [22]. Diet evolves over time, being influenced by many social and economic factors that interact in a complex manner to shape individual dietary patterns. These factors include income, food prices (which will affect the availability and affordability of healthy foods), individual preferences and beliefs, cultural traditions, and geographical and environmental aspects (including climate change). Therefore, promoting a healthy food environment – including food systems that promote a diversified, balanced and healthy diet – requires the involvement of multiple sectors and stakeholders, including government, and the public and private sectors [20].

Figure 4 shows five pathways on the food system which can have a negative impact on health and well-being. This is a guideline from World Health Organization to manage food system in delivering better health diets [20]. The first pathway includes aspects of the food system that lead to unhealthy diets or food insecurity and thus contribute to malnutrition in all its forms. Animal pathogens and antibiotic resistance is the second pathways. This includes wildlife being caught in the food supply chains and the use of antibiotics leading to zoonotic diseases and antibiotic resistance, leading to infectious diseases and diseases not transmissible in humans.

Dangerous and adulterated food is the following pathway. This pathways in the food system are the cause of various diseases (e.g., micronutrient deficiencies, stunting, emaciation, infectious and non-communicable diseases and mental illness) when food and Drinking water contains infectious or toxic hazards, microbial pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses and parasites, or chemical residues, contaminants or biological toxins. These contaminants can appear in unsafe food supply chains or in unhealthy environments or as a result of unsafe behaviors.

The environment is polluted and degraded pathway includes environmental pollution through the use in the food supply chain and the food environment with fertilizers, manures, products containing heavy metals, endocrine disrupting chemicals or stimulants. growth hormone, can cause different conditions, such as mental illness and other diseases -infectious diseases and infectious diseases. This includes how food production, the food environment and the behavior of citizens degrade the environment by emitting air pollutants, greenhouse gases and microplastics, affecting health and well-being.

Occupational risk is a pathway in the food system which can cause many impacts on the physical and mental health for farmers, fishermen, agricultural workers and those working in the retail sector such as processing and food chains. Impacts include stress from heat and cold, trauma, exposure to chemicals through the use of pesticides, fertilizers and insecticides, biological hazards such as snake bites, infectious diseases and parasites, zoonotic diseases, ergonomic hazards and psycho-social risks leading to stress and mental illness, including suicide.

Transforming food system to deliver health should change the narrative and decision makers on food system. The policy support should govern systemic changes for better health by implementing three pillars; mainstreaming the concept of healthy, sustainable diets; democratic, transparent, accountable governance frameworks; and accessible, credible interdisciplinary research.

Indonesia sustainable food system

Sustainable food system, including ensuring inclusive access, sustainable production and consumption, as well as minimizing food loss and waste is a priority. In the Sustainable Development Goal 2, food becomes important agenda to end hunger, to achieve food security and to improve nutrition as well as to promote sustainable agriculture.

Currently, the farming practices which is supply-oriented rather than demand-oriented is one of the indicator that food system in Indonesia is less sustainable [4, 11]. The use of chemical instead of promoting organic farming due to government subsidized fertilizers is another indicator for less sustainable agriculture. Moreover, the national food logistical and distribution are also supporting such practices.

Indonesia has been most focusing food self-sufficiency on rice, corn and soybean and the ministry of agriculture has push exported for fruit and horticulture product. The paradox between the abundance of food quantity, non-communicable diseases associated with dietary risk is even becoming the highest risk factor for mortality and disability in Indonesia. Therefore, Indonesia needs to change the conventional paradigm on food system to be able to reach sustainable food system.

The sustainable food system or it is called Pangan Bijak Nusantara (Wise Foodways of the Archipelago) consist of eight principles. This mandatory principle includes holistic, inclusive, local, life-cycle, interdependence, environmental and natural resources system and sustainability [16]. Figure 4 displays the concept of Indonesia Sustainability Food System (ISFS), which is based on family as the smallest system in the community to implement it. Families are the cores and spearheads in developing healthy, diverse and responsible food consumption pattern. The interaction among food actors and stakeholders across the food life cycle is the common ground of sustainable food system. The production and consumption that considering social, economic and cultural factors should be implemented consistently sustainable [20].

Preserving environment and natural resources are also concerned in the sustainable food system. It confirms that the system must work within the potential limits of the environment and natural resources. Food autonomy component is associated with the right to food selection, whereas the food sovereignty component is related with a nation’s capacity to provide by itself with all or a certain amount of food. Both components are the prerequisites for the realization of sustainable food system [16, 23].

Food security and nutrition are essentially the outputs of a sustainable food system. Individuals who are active, healthy, and productive are the system's outcomes. Indonesian community must choose diverse, healthy, and sustainable food as the country's food consumption pattern. The nutrition security from the availability of safe food at any time in sufficient quantity is the goal of the system. A clean and healthy lifestyle are the key point to achieved by all actors and stakeholders.

ISFS covers all stages of the food life cycle, not just production. The state must play an active role in the food system, particularly in ensuring food availability and price stability as mandated by the Food Act [16]. To ensure the success of ISFS, the Indonesian government must devise an appropriate incentive and disincentive system. Furthermore, all actors and stakeholders must be accommodated and guaranteed to participate actively. In short, ISFS must be participatory by definition. It is believed that the holistic achievement of a sustainable food system will contribute to meet the current needs for healthy and diverse food without risk future generations' ability to meet their own needs.

INTERVENTION, INNOVATION AND POLICY CONSIDERATION

Reinventing circular agriculture

In the view of agricultural economics, the circular economy has been widely adopted in the form of a smallholder integrated farming system, but it lacks improvement [6]. Integrated farming systems have been proven to combine food crops, horticultural crops and raising cattle into one cycle of production. At this point, farmers are gaining the circular economy routine [7]. Further, the concept of circular economy is in line with the idea of sustainable agriculture [7]. In this regard, sustainable farming is developed by less external input, and long-lasting participation of farm households. The improvement of organic farming, biological farming, bio-circular agriculture, and regenerative agriculture are the direction of a sustainable farming system [6, 25].

Moreover, circular agriculture is a part of the sustainable agriculture concept. By definition, this terminology includes any production and consumption model, which involves sharing, renting, reusing, repairing, renovating and recycling existing materials and products for as long as possible [26] and reducing to the minimum of waste” [15], offering a better alternative to the current model of economic development, the “take, do and dispose of” model [16] with a view to economic, environmental, and social sustainability [5].

In short, the differences between Circular Business Models (CBMs) and Linear Business Models (LBMs) relate to three aspects that is ownership, responsibility, and budget structure [27]. The ownership of a product in a CBMs, including its waste, remains with the seller. Business responsibility in CBMs focuses on environmental, social, and financial value propositions. The adoption of CBMs leads to differences in budget structure which include both cost and revenue streams. Organic waste is one of the core wastes in agriculture sector that preferably needs biological treatment. The green revolution effect causes farmers to use pesticides, herbicides which are harmful for human health. The biological pest control is then a win for the environment [5]. In the case of Indonesia, new technologies and innovation like the use of drone spray or related internet of things to operate agricultural equipment are introduced lately. Indonesian smallholders’ farmers should take the opportunity to be able to use drone technology, but the cost is not affordable for poor farmers. If farmers are part of a large farmers group or a cooperative, on that level, they would be able to lease a drone. New business cases need to be developed to reach the majority of farmers in Indonesia. The Indonesian government has to make it easier, in relation to policies and regulations, to make these innovations available and in reach of farmers [25].

Indonesia government has implemented a national project named Nucleus Estate Smallholders (NES) over 30 years. However, maintaining continuity and sustainability of the program is hardest challenge. The smallholder farmers remain left behind and less acknowledgement in the form of patron-client relation with the government and companies [6]. Therefore, to enhance the performance of this NES program, evaluation and redesigning of the NES program is expected to find an improved outcome for better business partnership among the stakeholders. Several cases have applied the concept of circular agriculture by fostering partnership between farmer and company as displayed in Table 2. Most of the company activities follow the guidance of sustainability concepts that is deploying a triple bottom line i.e. planet, people and profit as suggested by John Elkington (1994). Further, NGO and CSO have participated in and take benefit from circular agriculture activities.

Due to these effects, the Indonesian private sector has become more aware of the circularity aspect in their business and is showing its commitment to adopt circular business models. A survey of 57 Indonesian firms conducted as part of this research highlighted that the vast majority (almost 80 percent) have a strong willingness to engage in the development of a national circular economy strategy [15].

Table 2. Some initiatives to implement a circular economy in agricultural sectors.

No

Company

Partner

Program

Business Model

Innovation

1

Multi Bintang Indonesia.

Local cooperation (CV langgang Dumadi and KUD Budi Raharjo)

“Brewing a better world”

-Circular supply chain

-Product life cycle extension

- Using rice husks as renewable energy sources in biomass plant

- Zero waste to landfill

- Returnable bottle system

2

BIOS Agrotekno

No local partner as farmers are too afraid to adopt the new system.

Precision irrigation

Sharing platform

Automatic irrigation using IOTs is called ENCOMOTION.

3

Sarihusada (Danone Indonesia)

Lembaga Pengembangan Teknologi Pedesaan (Rural Technology Development Institute) in Yogyakarta and Central Java

Regenerative agricultural practices

Resources recovery

Built large-scale bio-digester for communal sheds in Merapi project.

4

Re>Pal

Farmer in East Java

Zero waste pallets

Resources recovery

zero waste pallets are made from 100% waste plastic using Re>Pal’s unique Thermo Fusion technology process.

5

PT Bukit Asam

Farmers at Pagar Dewa Village, Muara Enim Regency, South Sumatera

Industrial Central of Bukit Asam (Sentral Industri Bukit Asam) Program

Resources Recovery

Changing waste to energy (Solar Cell) as an engine for operating rice mill units, rice polisher, etc.

6

Ministry of Marines and Fisheries working together with Republic of France (IRD/GDA/CRIA)

Fishers at Singkut village, Jambi

Maggot Bio-conversion for fish meal replacement

Resource recovery

Fish meal replacement: Pellet for red gurame and Vanname Shrimps

Sources: various publications, 2022

In the "Brewing" program, producing biomass facilities use rice husks, sourced from local rice mills and collectors, to produce thermal energy. The burning of rice husks heats the boilers used for brewing and other business activities in the company's production process. Rice husks were previously perceived as waste by farmers. Using rice husks as an energy source hand over for it is usually free to take depending on the time of a year, but there may be transport costs involved. For example, in April 2020, 116 tons of rice husks were used, leaving out only 23.2 tons of rice husk ash. The rice husk ash was not wasted, as it was used in other ways. Ash with high silica content can be used as an ingredient in construction, brick making, poultry bedding, and powerful organic fertilizers, and through BECIS Bioenergy's CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) initiative, rice husk ash is given to community for free. Communities in Trawas, Sudimoro, Mojoranu, and also Sampangagung used this ash for composting (63.8 tons), brick making (17.6 tons) and construction material (6.6 tons). In addition, the circularity of this waste can be produced as spent grains and spent yeast which is semi liquid material, difficult to transport. These high nutrients for farming were sold to local cooperation such as CV Langgeng Dumadi, KUD Tritunggal, and KUD Budi Raharjo. They re-sell spent grains to local farmers. While, other partnership with dairy company PT Greenfields who uses the spent grains to feed their cows. PT Maqpro Biotech Indonesia is another partner who buys only our spent yeast, processing it to make feed for fish and shrimps [26].

In addition, leading consumer goods companies such as Unilever, Nestle, Indofood, Coca-Cola, Danone and Tetra Pak have established PRAISE, an organization that aims to accelerate the adoption of a circular economy in the private sector in Indonesia [25]. The company goal is to reduce the company's emissions intensity by 50% by 2030 and to eventually achieve net-zero emissions across Danone's entire emissions footprint. In relation to circular agriculture, Danone (Sari Husada) has established e large-scale bio-digester for communal sheds in ‘Merapi Project’, located in Umbulharjo, Cangkringan, Sleman, Yogyakarta [26]. This project has objective to increase farmer awareness about how to manage dairy cow dung as well as help them produce high quality feed for their dairy cows. Forage that is of high quality is needed to increase the total solid content in fresh milk, which can give a farmer a better price for his milk. Total solid fertilizer potential produced from this facility is around 3,000 Kg per month. A small amount of organic fertilizer is used by farmers to their own grass land, and the rest they sell for getting additional income.

In this regard, the circular economy has been mutually providing benefits to farmers. However, to improved integrated farming systems as a recycle economic activity has not been adequately captured by introducing new farming systems approach. To apply CBMs may incur extra costs to recycle agricultural waste, at least cost to transport the recycle waste to product or energy from the company stations to farmer land or home. The absence of social pressures and the presence of practical constraints likely explains why the respondents have not implemented relevant business strategies. For example, having a good partner as the appropriate early adopter is a challenge for companies to implement 6R concepts (Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Remanufacturing, Recycle, and Recover).

Enabling factor of circular agriculture

Business model in circular agriculture differs from classical business model. Maintaining good financial health, efficient use of resources and achieving long-term viability of the firm are the principle aims of this business model. It emphasizes the collaborative character, which require cooperation, communication and coordination with a wide range of stakeholders.

Figure 5 and Table 2 explain the barriers to implement circular agriculture practices. The critical success or barriers to implement circular agriculture are varied across firms, communities and nations. The complexity of sustainable food system is also reflected in this business model. Based on the literature reviews, there are some external and internal challenges that include lack of consumer acceptance of waste-based products, a missing willingness to invest in unsure and risky environmental innovations by businesses, a missing industry framework to seize and communicate sustainability to different stakeholders, climate change that causes investment fail, less profit compares to business as usual, price competitiveness with product without recycling process. Furthermore, Rizos et al. (2016) uncovered barriers for circular agriculture, including a lack of support from the supply and demand network, insufficient capital for investment, and also sometimes a lack of government support, of technical know-how or administrative burdens. Internal barriers were a lack of knowledge and technology, organizational and financial structures, and external barriers were related to the supply chain, markets and institutions (e.g., policies, standards) [28].

Meanwhile, the sequential factors for translating circular agriculture into a new business model are collaboration, continuous innovation, a clear history and vision, profitability, commitment to sustainability and external events such as consumers’ trends or food crises. An important way to promote circular systems that is to improve information connections across the food system from consumers to producers. Experience with the positive impact of organic certification and labeling programs on the development of the organic food industry demonstrates the potential of such policies to translate consumer demand for producers through positive price signals [29].

Setting standards for circular and sustainable food production practices and related product certification and labeling would provide a market-based mechanism to reward private investments in more circular and sustainable technologies and their adoption by farmers [25]. Hence, the development of more efficient food markets also requires public and private investments in better data and information systems that can credibly convey information on farm production practices across the food system to consumers. In doing so, having sustainable technology innovation center that is completely integrated into the production chain will benefit companies to sustain their business [28]. Building perspectives on the role of waste management service providers are positive as it can be tool to help them to be more effectively practicing good handling food management in their supply chain process. To convince farmers and other stakeholders to participate in this business, therefore, persuasive communication can be effective by helping farmer’s stakeholders to see the financial feasibility of adopting a circular economy model.

Diverse healthy food

Besides promoting circular agriculture, food diversity is also part of the strategy in a sustainable food system. The “Isi Piringku” (My Plate) initiative, a government program on healthy diets designed to support food diversity. Food diversity has been marginalized while at the same time dismissing local food potentials and its various wisdom that have been proven as high resilience [16, 23].

Indonesia enriches with local agri-food that provide nutrition and health among low-income urban and rural consumers. Agri-food value chains serve as a vehicle to connect producers who are often in rural areas, with consumers in peri-urban and urban areas. “My Plate” can be suited with food resources available in each region. Diversity of food across region can be served in the “my Plate” and “My local Plate” menu. Each region may differ in food type in term of its carbohydrate, protein, vegetables, fruits and even seasoning sources. However, the proportion of “My plate” shall include a half portion of vegetable and fruits, and a half another is staple food and side dishes [16].