ABSTRACT

In Upper Northern Thailand, most of native chicken farmers in rural areas are elderly. This paper provides an analysis of commercial viability of native chicken farming as an alternative for job opportunities among elder farmers in Phayao Province. Since all processes could not be carried out by one person, chicken farmers got together to establish systematic production. As the group members were elder people, farmers supported one another by allocating activities according to their skills and experiences among the group members. The production system has changed from farming for household consumption and for local markets to semi-confinement system, requiring production planning as well as marketing planning in order to supply chickens to the market all-year round. Some representatives of the group piloted in marketing by selling 3-4 whole chickens/day at the market. Moreover, a processed chicken meat such as chicken noodles, stir-fried chicken, and Thai chicken sausage added value to the farming by selling chicken products in the community. Four groups of chicken farmers in Phayao Province showed over 1% of Return on Investment. This implied that raising chickens could be developed as commercial career. Nevertheless, marketing planning process still needed some support from the public sector. Hence, public and academic support on farming as well as providing necessary inputs could improve native chicken production. Enhancing the standard of raising chickens also ensured a stable market. As a result, developing quality standard farming will create better opportunity for native chicken business; thus, commercial native chicken farming has a potential for the elderly in rural areas for job creation and for sources of income.

Keywords: Native chicken, Ageing population, Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Completely aged society is a society or country in which the population aged 60 years or over exceeds 20% of the total population, or a population aged 65 years or over exceeds 14% of the total population. Data from the Ministry of Public Health reported that in 2020, Thai people aged 60 years or over is more than 12 million or 18% of the total population and are expected to rise to 20% by 2021. This implies that Thailand has already entered the aged society and it is becoming a completely aged society soon. The National Statistical Office anticipates that Thailand will enter the completely aged society in 2022, and in 2030, the proportion of elder population will increase to 26.9% of the total population (Department of Mental Health, 2020). This means that 1 in 4 people in Thailand will be an elderly. When Thailand has entered the aged society, the government has to provide for more welfare both in the form of quantity and quality to serve the increasing number of the elderly, as a result, the government has to spend more expense (Thailand Development Research Institute, 2021). Hence, the government sector must prepare suitable housing and environment, support financial and health planning after retirement, and secure the equal income in order to establish a fair and just aged society as well as provide equal welfare and promote career for the people (Thai Health Promotion Foundation, 2021).

Some guidelines for promoting career for Thai elderly are: 1) career education must be provided for career development; 2) information about career planning should be informed for career selecting consideration; and 3) career counseling should be formed to enable target determining, career planning, and career developing more appropriately (Chetsanee, 2018). According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, with physical, mental and social relations, suitable jobs for older people should be flexible with less physical demand and require less sensory perception or less memory skill. The jobs should have low-stress in terms of work situation, but create opportunity for older workers to be accepted to join a task with other colleagues and society (Patcharapong et al., 2018). From these reasons, native chicken farming is one of the suitable careers for supporting older persons in the rural areas. Rural population raise native chickens for food, for income, and for community rituals (Preeyanan, 2015). According to research about promoting raising native chickens for farmers in the Upper Northern Thailand, since 2015, it was revealed that most of native chicken farmers are older people who were used to raise chickens. These elderlies do not want to depend on their children. They want to earn their own incomes in order to enhance their self-esteem. However, the production system must be changed from raising chickens as a source of food for families and for the local market into semi-confinement system under production planning and marketing planning so that chickens can be supplied to the market all-year round. Since all processes cannot be carried out by one person, chicken farmers get together to establish systematic production. Regarding marketing planning, the groups need some advice from the government sector to reduce marketing risk (Bunyat and Monchai, 2012). This paper provides a case study of native chicken farming in Phayao Province to illustrate job opportunities for ageing population in rural area.

SCOPE OF THE STUDY

To illustrate the potential job opportunities for rural ageing farmers, the case study of native chicken farming covers native chicken farmers who joined the native chicken bank project of Phayao Provincial Livestock Office in Phayao Province located in Northern Thailand. The native chicken bank project of Phayao Provincial Livestock Office in Phayao Province was established in 2021 with budget of 10,000 THB/year. The objectives were to develop the career, distribute and conserve the native chickens as well as to form the link of farmers’ network and improve the standard farm (Good Agricutlural Practice). The project covered 9 districts. One hundred and twenty six farmers from 5 districts participated in the project. That included 2 persons from Muang, 68 persons from Chiang Kham, 33 persons from Chun, 12 persons from Pong, and 11 persons from Dok Kamtai. As the samples, rural ageing farmers participated in this project. Qualifications of applicants were Thai nationality, aged 18 years old or above, farming career and poor. The condition was that 2 free sets of chicken breeders were given to each member of the enterprise groups. Each set of chicken comprised of 1 male and 5 female chickens. Each farmer raised and multiplied the given chicken for 1 year, and then returned 20 chickens back to Phayao Provincial Livestock Office for subsequent distribution to other members. If chickens died, the farmers had to pay for the dead chicken according to the real price of broiler chickens sold at the market such as 80 THB/bird. There were 4 groups, 64 members in this project (Figure 1) as followed:

- 19 members of Bua Stan (BS) Community Enterprise, Huai Khao Kam sub-district, Chun district.

- 27 members of Waen Kong (WK) Community Enterprise, Fai Kwang sub-district, Chiang Kham district.

- 14 members of Doi Esan (DE) Community Enterprise, Angthong sub-district, Chiang Kham district.

- 4 mebers of Kok Nongnha Model (KNM), Chun sub-district, Chun district.

COST PROFIT AND RETURNS OF NATIVE CHICKEN FARMING IN PHAYAO PROVINCE

General information of native chicken farmer’s groups

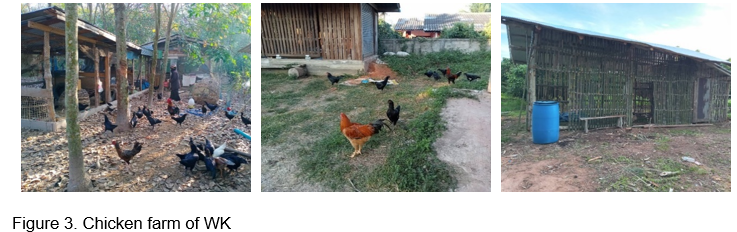

Farmers living in rural areas gathered together as community enterprise groups and then joined the native chicken bank project of Phayao Province. There were 64 members. 34 members (53.13%) were male whereas 30 members (46.88%) were female. There were 20 farmers (31.25%) aged over 60 years old, 18 farmers (28.13%) aged between 50 and 59 years old, 22 farmers (34.38%) aged between 40 and 49 years old. Most of them (54.69%) graduated from elementary school, and 51 persons (79.69%) are married (Table 1). Patterns of group setting and raising native chickens were divided into 4 groups as followed:

1) Bua Stan (BS) Community Enterprise. This group had been set up for 6 months. There were 30 native chickens per household. In this chicken farming system, hens were allowed to incubate their eggs naturally, and chickens were fed (Figure 2) for selling and returning to the native chicken bank within a year. Most of the farmers were 60-80 years old. The problems found included the high cost of raising native hens for egg, farmers had only very basic knowledge about raising chickens, farmers needed efficient egg incubator, they wanted to reduce cost of chicken feed, and they wanted good marketing for native chicken meat.

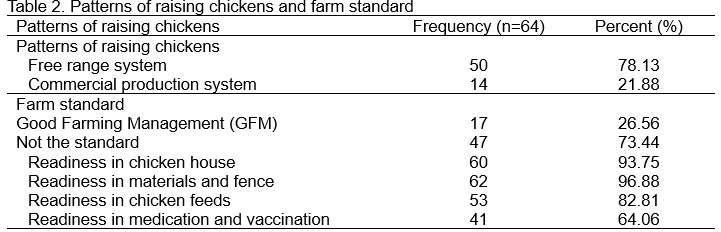

2) Waen Kong (WK) Community Enterprise. This group had been set up for 5 years. In these small-scale farms, chickens were raised to be breeders (Figure 3). The problems found included the lack of knowledge about raising chickens, constructing chicken houses, space for rearing chickens was limited to only 40 birds, and marketing problems.

3) Doi Esan (DE) Community Enterprise. They were small-scale chicken farms. Native chicken (Leung Bussarakham), bred by crossing native chicken breed with Huai Hong Khrai chickens (Figure 4), was considered the unique breed and symbol of Chiang Kham district (Geographical Indications: GI). Each member of this community enterprise group had to pay 500 THB for the venture. The problems found included the Huai Hong Khrai chicken breed was rare, and the lack of academic knowledge.

4) Kok Nongnha Model (KNM). The group had been set up for 3 months. Members were released from prison, and developed their career as chicken farmers to supplement their incomes. In these small-scale chicken farms, 30 chickens under native chicken bank project were given to each farmer (Figure 5). The farmers were 40-50 years old. They just started working in the farm, so they did not have any marketing plan. They had little knowledge about raising chickens, and there was no electricity in their farms.

Patterns of raising native chickens

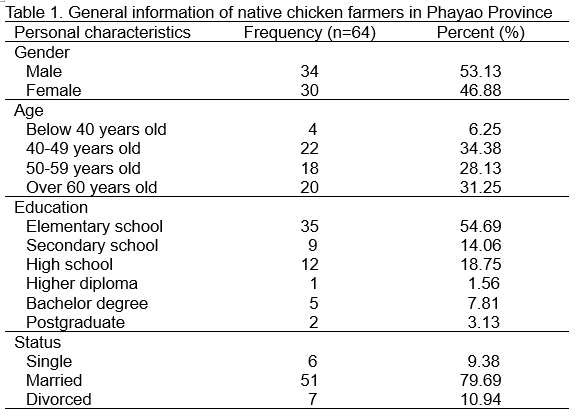

The selected enterprise groups were supported by Phayao Provincial Livestock Office under the native chicken bank project. The condition was that 2 free sets of chicken breeders were given to each member of the enterprise groups. Each set of chicken comprised of 1 male and 5 female chickens. Each farmer raised and multiplied the given chicken for 1 year, and then returned 20 chickens back to Phayao Provincial Livestock Office for subsequent giving to other members. If chickens died, the farmers had to pay for the dead chicken according to the real price of broiler chickens sold at the market such as 80 THB/bird[1]. All 4 groups of farmers who participated in the project had to prepare for raising chickens. Fences should be constructed to prevent dog and snake problems. Chickens raised under semi free-range system should be taken care about 4 hours/day – 2 hours in the morning, and 2 hours in the evening. 50 farmers (78.13%) raised chicken under the free range system while 14 farmers (21.88%) raised their chickens under commercial production system. Seven farms (26.56%) obtained Good Farming Management (GFM) standard while the rest were developing their practice so that they would meet the standard in the future. Sixty farmers (93.75%) had prepared their chicken houses. Sixty-two farmers (96.88%) had prepared the materials and fences. Fifty-three farmers (82.81%) were ready for chicken feed while 41 (64.06%) farmers prepared chicken medication and vaccination (Table 2). It took about 85 days to raise chicken for meat to maturity/round. The survival rate of fattening chickens was 70.04% in average. Some farmers kept some fattening chickens (6 birds/round) to be breeders. Knowledge about raising native chickens needed by farmers included how to raise chicken for consumption, incubation, knowledge about chicken disease and treatment, vaccination programs, and how to make chicken feed to reduce cost. Regarding the assistance in native chicken marketing, the farmers required constant marketing, and reasonable price or high selling price of chickens. As chickens were raised under the semi free-range system, they were free and happy. This resulted in better quality of chicken meat, and it also created networks in producing and selling. However, the enterprise groups still needed support on chicken breeders, chicken house, and standard incubator for better production.

Commercial opportunity to raise native chickens as a career

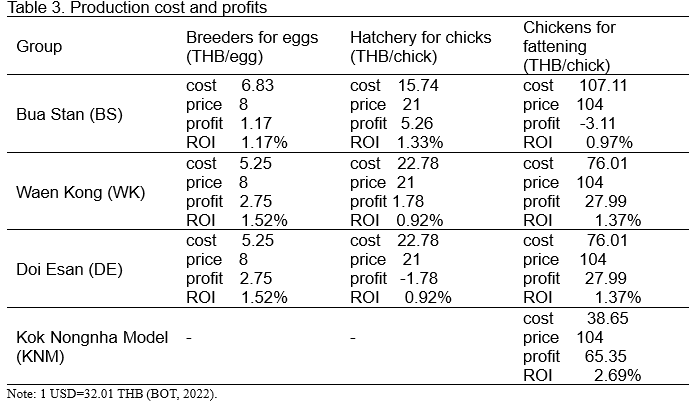

The cost of raising breeders for fertile chicken egg of BS group was 6.83 THB/egg. Each egg was 8 THB. The profit was 1.17 THB/egg. Return on Investment (ROI) was 1.17%. The farmers were encouraged to apply high quality incubator for better hatchability of eggs and reduce the pecking and sucking of the eggs by the hens. After the hatched chicks had received vaccination, they were sold at the price of 21 THB/chick. The cost was 15.74 THB/chick, profit was 5.26 THB/chick, ROI was 1.33%. However, some members, who raised fattening chickens, spent 107 THB/chick but the selling price was 104 THB/chick. So, they lost 3.11 THB/chick, ROI was 0.97%

Community enterprise group of WK and DE, both groups had the same cost and profit as they participated in native chicken bank project at the same time. The cost of raising breeders for fertile chicken egg was 5.25 THB/egg. The selling price of each egg was 8 THB/egg, profit was 2.75 THB/egg, ROI was 1.5%. Both groups were supported by incubators from Phayao Provincial Livestock Office. The cost was 22.78 THB/chick. The selling price was 21 THB/chick. So, they lost 1.75 THB/chick, ROI was 0.92%. While the members, who raised fattening chickens, spent the cost at 76.01 THB/chick. The selling price was 104 THB/chick. So, they got 27.99 THB/chick, ROI was 1.37%. KNM group said that the members were those who were released from prison and encouraged to work as chicken farmers for income earning. They were supported through the sales of fattening chickens from native chicken bank project. The cost was 38.65 THB/chick. The selling price was 104 THB/chick, the profit was 65.35 THB/chick, ROI was 2.69%.

The ROI of all 4 groups of chicken farmers was over 1%. This showed that raising native chickens for commerce could be developed to be a career or as an alternative career for older farmers in rural areas. For instance, Mr. Sukham, a representative from community enterprise group of BS, had piloted the marketing. He sold 3-4 whole chickens at the market every evening, and he got the profit at 20-30 THB/chick. So, his net income was 90-120 THB/day (Figure 6). Moreover, Mrs. Ampai, a representative from community enterprise group of WK, had piloted chicken meat processing such as chicken noodle, stir-fried chicken, Northern Thai chicken sausage, and Thai chicken sausage esan style for selling in community (Figure 7). The detailed income obtained from each menu was as followed:

1) Stir-fried chicken, 5 chickens (6 kg.)/pot were used in this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 600 THB, and ingredients cost 150 THB. Total cost for this menu was 750 THB/pot. The vendors scooped a portion of stir-fried chicken into a bag for a customer's order. It cost 50 THB/bag. Total income was 1,050 THB, profit was 300 THB/pot.

2) Chicken noodles, 5 chickens (5-6 kg.)/pot were used in this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 600 THB, and ingredients cost 200 THB. Total cost for this menu was 800 THB/noodle soup pot. It cost 30-40 THB/noodle bowl. Total income was 1,200 THB, profit was 400 THB/noodle soup pot.

3) Northern Thai chicken sausage, 2 chickens (1.5 kg.)/pot were used for this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 200 THB, and ingredients cost 100 THB. Total cost was 300 THB/pot. The sausage was sold at the price of 35 THB/gram. Total price was 560 THB, profit was 260 THB/pot.

4) Thai chicken sausage esan style, 2 chickens (1.5 kg.)/pot were used in this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 200 THB, and ingredients cost 60 THB. Total cost was 260 THB/pot. The sausage was sold at the price of 35 THB/gram. Total price was 560 THB, profit as 300 THB/pot.

The results revealed that selling broiler chickens, and processing chicken meat products could generate incomes for farmers in rural areas. However, it depended on the age and potential of each farmer. Some elderly, who were powerless, only raised chickens and then sold fattening chickens to other members who would kill and sold chicken meat at the market. This showed that the farmers mutually helped and cooperated in their group since they knew they had different potential and marketing skills. According to the research findings of Teeka et al. (2015), customers in Phrae Province in the Northern Thailand were willing to pay 107.88 THB/kg for chicken meat because it was widely available and had good quality. The study also showed that factors influencing consumers decision to buy Pradu Hang Dam chicken meat included customers’ education level and knowledge about Pradu Hang Dam chicken characteristics (Nalinee et al, 2018). Pradu Hang Dam chicken meat had higher protein content with low fat and low cholesterol. Its meat was characteristically tough and more delicious than other native chickens. Regarding career needs, the elderly in rural areas needed differently as compared from the elderly in Bangkok, who needed art-related jobs such as cooking, making desserts, and crafting (Apisada, 2011). On the other hand, socio-economic factors likely to influence local chicken production include the average number of chickens, ownership of chickens in the household, flock owner main activity, method of breeding stock acquisition, reason for keeping indigenous chicken and production objectives (Adoligbe et al., 2020). Thus, the opportunity of aging rural population can get a job of native chicken farming. Even though they were powerless but chicken got them the income they needed for living and happiness and also for their self esteem.

CONCLUSION

There is an opportunity for elder farmers in rural areas to raise native chickens for commerce. Native chicken farming shows positive pay offs, over 1% of ROI on average. As farmers can find chicken supplements in their local areas, this implies reduced production cost. Moreover, older farmers who have plenty of free time, can fully provide good care for chickens. Raising native chickens also helps in improving the health of older people, and reduced their depression and loneliness. However, raising chickens for commerce differs from backyard raising chickens. It requires more cost for constructing standard chicken houses as well as feeding system and vaccination. This case study shows that farmers who are members of community enterprise can obtain some assistance from government project. For example, the farmers under the native chicken bank project of Phayao Province have obtained academic drives from government sectors that include university, Department of Livestock Development which provide knowledge about raising chickens as well as materials such as standard incubator, vaccination management. These forms of support enable farmers to supply chickens to the market all-year round and improve quality which leads to marketing confidence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) for providing funding for this research study. We also would like to thank the Community Enterprises in Phayao Province for providing information and good cooperation in our field work. Finally, we would like to express our sincere thanks to Maejo University - Phrae Campus for allowing us to work on this research study.

REFERENCES

Adoligbe, C. et al. (2020). Native chicken farming: A tool for wealth creation and food security in Benin. International Journal of Livestock Production, 11(4): 146-162.

Apisada Lao Wattanapong. (2011). Needs and give direction to the social welfare policy among elderly people in the Bangkok Metropolitan area. Academic Services Journal, Prince of Songkla University, 22(3): 56-67.

Bank of Thailand (BOT). (2022). Exchange rate at Jan-Dec 2021. Retrived August, from Bank of Thailand: https://www.bot.or.th/App/BTWS_STAT/statistics/ReportPage.aspx?reportID=...

Bunyat Loaphaibool and Monchai Duangjinda. (2012). Native chicken: Past Present and Future. KHON KAEN AGR. J., 40: 309-312.

Chetsanee Chantawong. (2018). Career development of elderly in Thailand. In the preceding on conference ASEAN on the Path of Community. 3 December 2018 at Faculty of Political Science, Ramkhamhaeng University.

Department of Mental Health. (2020). Forward aged society in Thailand. Retrived February, from Department of Mental Health: https://www.dmh.go.th/news-dmh/view.asp?id=30476

Ketsara Phoyen. (2019). Aging Society: Opportunities for the Future Sustainable Business. Journal of Management Science Review, 21(1): 201-209.

Nalinee Kongsuban, Worasin Malaithong, Anugul Junkaew and Teeka Yotapakdee. (2018). Factors Influencing Consumer Purchasing Decision of Safety Pradu-Hangdum Chicken in Phrae Province. KHON KAEN AGR. J., 46(4): 675-686.

Preeyanan Prasertia. (2015). Management learning communities to engage in honest livelihood tambon Donyhoen ChengYern district, Mahasarakham province. Master degree of Educational Program, Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University.

Patcharapong Chuanchom, Thirawat Chantuk, and Phitak Siriwong. (2018). Job styles for older workers. VRU Research and Development Journal Science and Technology, 13(1): 107-116.

Teeka Yotapakdee, Nalinee Kongsubun, Worasin Malithong and Savichaya Supaudomlerk Trirat. (2015). Opportunity of Free-range Native Chickens for Rural Enterprise Development in Phrae Province. KAEN AGR. J., 43(Supplement 2, 2015), 63-66.

Thai Health Promotion Foundation. (2021). Awareness aged society and highly expenses. Retrived February, from Thai Health Promotion Foundation: https://resourcecenter.thaihealth.or.th/article

Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI). (2012). Aged society project and budget. Office of Promotion and Protection of Children, Youth, the Elderly and Vulnerable Groups.

[1] average exchange rate (Jan-Dec 2021) 1 USD=32.01 THB (BOT, 2022)

Ageing Rural Population and Job Opportunities: A Case of Native Chicken Farming

ABSTRACT

In Upper Northern Thailand, most of native chicken farmers in rural areas are elderly. This paper provides an analysis of commercial viability of native chicken farming as an alternative for job opportunities among elder farmers in Phayao Province. Since all processes could not be carried out by one person, chicken farmers got together to establish systematic production. As the group members were elder people, farmers supported one another by allocating activities according to their skills and experiences among the group members. The production system has changed from farming for household consumption and for local markets to semi-confinement system, requiring production planning as well as marketing planning in order to supply chickens to the market all-year round. Some representatives of the group piloted in marketing by selling 3-4 whole chickens/day at the market. Moreover, a processed chicken meat such as chicken noodles, stir-fried chicken, and Thai chicken sausage added value to the farming by selling chicken products in the community. Four groups of chicken farmers in Phayao Province showed over 1% of Return on Investment. This implied that raising chickens could be developed as commercial career. Nevertheless, marketing planning process still needed some support from the public sector. Hence, public and academic support on farming as well as providing necessary inputs could improve native chicken production. Enhancing the standard of raising chickens also ensured a stable market. As a result, developing quality standard farming will create better opportunity for native chicken business; thus, commercial native chicken farming has a potential for the elderly in rural areas for job creation and for sources of income.

Keywords: Native chicken, Ageing population, Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Completely aged society is a society or country in which the population aged 60 years or over exceeds 20% of the total population, or a population aged 65 years or over exceeds 14% of the total population. Data from the Ministry of Public Health reported that in 2020, Thai people aged 60 years or over is more than 12 million or 18% of the total population and are expected to rise to 20% by 2021. This implies that Thailand has already entered the aged society and it is becoming a completely aged society soon. The National Statistical Office anticipates that Thailand will enter the completely aged society in 2022, and in 2030, the proportion of elder population will increase to 26.9% of the total population (Department of Mental Health, 2020). This means that 1 in 4 people in Thailand will be an elderly. When Thailand has entered the aged society, the government has to provide for more welfare both in the form of quantity and quality to serve the increasing number of the elderly, as a result, the government has to spend more expense (Thailand Development Research Institute, 2021). Hence, the government sector must prepare suitable housing and environment, support financial and health planning after retirement, and secure the equal income in order to establish a fair and just aged society as well as provide equal welfare and promote career for the people (Thai Health Promotion Foundation, 2021).

Some guidelines for promoting career for Thai elderly are: 1) career education must be provided for career development; 2) information about career planning should be informed for career selecting consideration; and 3) career counseling should be formed to enable target determining, career planning, and career developing more appropriately (Chetsanee, 2018). According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, with physical, mental and social relations, suitable jobs for older people should be flexible with less physical demand and require less sensory perception or less memory skill. The jobs should have low-stress in terms of work situation, but create opportunity for older workers to be accepted to join a task with other colleagues and society (Patcharapong et al., 2018). From these reasons, native chicken farming is one of the suitable careers for supporting older persons in the rural areas. Rural population raise native chickens for food, for income, and for community rituals (Preeyanan, 2015). According to research about promoting raising native chickens for farmers in the Upper Northern Thailand, since 2015, it was revealed that most of native chicken farmers are older people who were used to raise chickens. These elderlies do not want to depend on their children. They want to earn their own incomes in order to enhance their self-esteem. However, the production system must be changed from raising chickens as a source of food for families and for the local market into semi-confinement system under production planning and marketing planning so that chickens can be supplied to the market all-year round. Since all processes cannot be carried out by one person, chicken farmers get together to establish systematic production. Regarding marketing planning, the groups need some advice from the government sector to reduce marketing risk (Bunyat and Monchai, 2012). This paper provides a case study of native chicken farming in Phayao Province to illustrate job opportunities for ageing population in rural area.

SCOPE OF THE STUDY

To illustrate the potential job opportunities for rural ageing farmers, the case study of native chicken farming covers native chicken farmers who joined the native chicken bank project of Phayao Provincial Livestock Office in Phayao Province located in Northern Thailand. The native chicken bank project of Phayao Provincial Livestock Office in Phayao Province was established in 2021 with budget of 10,000 THB/year. The objectives were to develop the career, distribute and conserve the native chickens as well as to form the link of farmers’ network and improve the standard farm (Good Agricutlural Practice). The project covered 9 districts. One hundred and twenty six farmers from 5 districts participated in the project. That included 2 persons from Muang, 68 persons from Chiang Kham, 33 persons from Chun, 12 persons from Pong, and 11 persons from Dok Kamtai. As the samples, rural ageing farmers participated in this project. Qualifications of applicants were Thai nationality, aged 18 years old or above, farming career and poor. The condition was that 2 free sets of chicken breeders were given to each member of the enterprise groups. Each set of chicken comprised of 1 male and 5 female chickens. Each farmer raised and multiplied the given chicken for 1 year, and then returned 20 chickens back to Phayao Provincial Livestock Office for subsequent distribution to other members. If chickens died, the farmers had to pay for the dead chicken according to the real price of broiler chickens sold at the market such as 80 THB/bird. There were 4 groups, 64 members in this project (Figure 1) as followed:

- 19 members of Bua Stan (BS) Community Enterprise, Huai Khao Kam sub-district, Chun district.

- 27 members of Waen Kong (WK) Community Enterprise, Fai Kwang sub-district, Chiang Kham district.

- 14 members of Doi Esan (DE) Community Enterprise, Angthong sub-district, Chiang Kham district.

- 4 mebers of Kok Nongnha Model (KNM), Chun sub-district, Chun district.

COST PROFIT AND RETURNS OF NATIVE CHICKEN FARMING IN PHAYAO PROVINCE

General information of native chicken farmer’s groups

Farmers living in rural areas gathered together as community enterprise groups and then joined the native chicken bank project of Phayao Province. There were 64 members. 34 members (53.13%) were male whereas 30 members (46.88%) were female. There were 20 farmers (31.25%) aged over 60 years old, 18 farmers (28.13%) aged between 50 and 59 years old, 22 farmers (34.38%) aged between 40 and 49 years old. Most of them (54.69%) graduated from elementary school, and 51 persons (79.69%) are married (Table 1). Patterns of group setting and raising native chickens were divided into 4 groups as followed:

1) Bua Stan (BS) Community Enterprise. This group had been set up for 6 months. There were 30 native chickens per household. In this chicken farming system, hens were allowed to incubate their eggs naturally, and chickens were fed (Figure 2) for selling and returning to the native chicken bank within a year. Most of the farmers were 60-80 years old. The problems found included the high cost of raising native hens for egg, farmers had only very basic knowledge about raising chickens, farmers needed efficient egg incubator, they wanted to reduce cost of chicken feed, and they wanted good marketing for native chicken meat.

2) Waen Kong (WK) Community Enterprise. This group had been set up for 5 years. In these small-scale farms, chickens were raised to be breeders (Figure 3). The problems found included the lack of knowledge about raising chickens, constructing chicken houses, space for rearing chickens was limited to only 40 birds, and marketing problems.

3) Doi Esan (DE) Community Enterprise. They were small-scale chicken farms. Native chicken (Leung Bussarakham), bred by crossing native chicken breed with Huai Hong Khrai chickens (Figure 4), was considered the unique breed and symbol of Chiang Kham district (Geographical Indications: GI). Each member of this community enterprise group had to pay 500 THB for the venture. The problems found included the Huai Hong Khrai chicken breed was rare, and the lack of academic knowledge.

4) Kok Nongnha Model (KNM). The group had been set up for 3 months. Members were released from prison, and developed their career as chicken farmers to supplement their incomes. In these small-scale chicken farms, 30 chickens under native chicken bank project were given to each farmer (Figure 5). The farmers were 40-50 years old. They just started working in the farm, so they did not have any marketing plan. They had little knowledge about raising chickens, and there was no electricity in their farms.

Patterns of raising native chickens

The selected enterprise groups were supported by Phayao Provincial Livestock Office under the native chicken bank project. The condition was that 2 free sets of chicken breeders were given to each member of the enterprise groups. Each set of chicken comprised of 1 male and 5 female chickens. Each farmer raised and multiplied the given chicken for 1 year, and then returned 20 chickens back to Phayao Provincial Livestock Office for subsequent giving to other members. If chickens died, the farmers had to pay for the dead chicken according to the real price of broiler chickens sold at the market such as 80 THB/bird[1]. All 4 groups of farmers who participated in the project had to prepare for raising chickens. Fences should be constructed to prevent dog and snake problems. Chickens raised under semi free-range system should be taken care about 4 hours/day – 2 hours in the morning, and 2 hours in the evening. 50 farmers (78.13%) raised chicken under the free range system while 14 farmers (21.88%) raised their chickens under commercial production system. Seven farms (26.56%) obtained Good Farming Management (GFM) standard while the rest were developing their practice so that they would meet the standard in the future. Sixty farmers (93.75%) had prepared their chicken houses. Sixty-two farmers (96.88%) had prepared the materials and fences. Fifty-three farmers (82.81%) were ready for chicken feed while 41 (64.06%) farmers prepared chicken medication and vaccination (Table 2). It took about 85 days to raise chicken for meat to maturity/round. The survival rate of fattening chickens was 70.04% in average. Some farmers kept some fattening chickens (6 birds/round) to be breeders. Knowledge about raising native chickens needed by farmers included how to raise chicken for consumption, incubation, knowledge about chicken disease and treatment, vaccination programs, and how to make chicken feed to reduce cost. Regarding the assistance in native chicken marketing, the farmers required constant marketing, and reasonable price or high selling price of chickens. As chickens were raised under the semi free-range system, they were free and happy. This resulted in better quality of chicken meat, and it also created networks in producing and selling. However, the enterprise groups still needed support on chicken breeders, chicken house, and standard incubator for better production.

Commercial opportunity to raise native chickens as a career

The cost of raising breeders for fertile chicken egg of BS group was 6.83 THB/egg. Each egg was 8 THB. The profit was 1.17 THB/egg. Return on Investment (ROI) was 1.17%. The farmers were encouraged to apply high quality incubator for better hatchability of eggs and reduce the pecking and sucking of the eggs by the hens. After the hatched chicks had received vaccination, they were sold at the price of 21 THB/chick. The cost was 15.74 THB/chick, profit was 5.26 THB/chick, ROI was 1.33%. However, some members, who raised fattening chickens, spent 107 THB/chick but the selling price was 104 THB/chick. So, they lost 3.11 THB/chick, ROI was 0.97%

Community enterprise group of WK and DE, both groups had the same cost and profit as they participated in native chicken bank project at the same time. The cost of raising breeders for fertile chicken egg was 5.25 THB/egg. The selling price of each egg was 8 THB/egg, profit was 2.75 THB/egg, ROI was 1.5%. Both groups were supported by incubators from Phayao Provincial Livestock Office. The cost was 22.78 THB/chick. The selling price was 21 THB/chick. So, they lost 1.75 THB/chick, ROI was 0.92%. While the members, who raised fattening chickens, spent the cost at 76.01 THB/chick. The selling price was 104 THB/chick. So, they got 27.99 THB/chick, ROI was 1.37%. KNM group said that the members were those who were released from prison and encouraged to work as chicken farmers for income earning. They were supported through the sales of fattening chickens from native chicken bank project. The cost was 38.65 THB/chick. The selling price was 104 THB/chick, the profit was 65.35 THB/chick, ROI was 2.69%.

The ROI of all 4 groups of chicken farmers was over 1%. This showed that raising native chickens for commerce could be developed to be a career or as an alternative career for older farmers in rural areas. For instance, Mr. Sukham, a representative from community enterprise group of BS, had piloted the marketing. He sold 3-4 whole chickens at the market every evening, and he got the profit at 20-30 THB/chick. So, his net income was 90-120 THB/day (Figure 6). Moreover, Mrs. Ampai, a representative from community enterprise group of WK, had piloted chicken meat processing such as chicken noodle, stir-fried chicken, Northern Thai chicken sausage, and Thai chicken sausage esan style for selling in community (Figure 7). The detailed income obtained from each menu was as followed:

1) Stir-fried chicken, 5 chickens (6 kg.)/pot were used in this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 600 THB, and ingredients cost 150 THB. Total cost for this menu was 750 THB/pot. The vendors scooped a portion of stir-fried chicken into a bag for a customer's order. It cost 50 THB/bag. Total income was 1,050 THB, profit was 300 THB/pot.

2) Chicken noodles, 5 chickens (5-6 kg.)/pot were used in this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 600 THB, and ingredients cost 200 THB. Total cost for this menu was 800 THB/noodle soup pot. It cost 30-40 THB/noodle bowl. Total income was 1,200 THB, profit was 400 THB/noodle soup pot.

3) Northern Thai chicken sausage, 2 chickens (1.5 kg.)/pot were used for this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 200 THB, and ingredients cost 100 THB. Total cost was 300 THB/pot. The sausage was sold at the price of 35 THB/gram. Total price was 560 THB, profit was 260 THB/pot.

4) Thai chicken sausage esan style, 2 chickens (1.5 kg.)/pot were used in this menu. The cost of chicken meat was 200 THB, and ingredients cost 60 THB. Total cost was 260 THB/pot. The sausage was sold at the price of 35 THB/gram. Total price was 560 THB, profit as 300 THB/pot.

The results revealed that selling broiler chickens, and processing chicken meat products could generate incomes for farmers in rural areas. However, it depended on the age and potential of each farmer. Some elderly, who were powerless, only raised chickens and then sold fattening chickens to other members who would kill and sold chicken meat at the market. This showed that the farmers mutually helped and cooperated in their group since they knew they had different potential and marketing skills. According to the research findings of Teeka et al. (2015), customers in Phrae Province in the Northern Thailand were willing to pay 107.88 THB/kg for chicken meat because it was widely available and had good quality. The study also showed that factors influencing consumers decision to buy Pradu Hang Dam chicken meat included customers’ education level and knowledge about Pradu Hang Dam chicken characteristics (Nalinee et al, 2018). Pradu Hang Dam chicken meat had higher protein content with low fat and low cholesterol. Its meat was characteristically tough and more delicious than other native chickens. Regarding career needs, the elderly in rural areas needed differently as compared from the elderly in Bangkok, who needed art-related jobs such as cooking, making desserts, and crafting (Apisada, 2011). On the other hand, socio-economic factors likely to influence local chicken production include the average number of chickens, ownership of chickens in the household, flock owner main activity, method of breeding stock acquisition, reason for keeping indigenous chicken and production objectives (Adoligbe et al., 2020). Thus, the opportunity of aging rural population can get a job of native chicken farming. Even though they were powerless but chicken got them the income they needed for living and happiness and also for their self esteem.

CONCLUSION

There is an opportunity for elder farmers in rural areas to raise native chickens for commerce. Native chicken farming shows positive pay offs, over 1% of ROI on average. As farmers can find chicken supplements in their local areas, this implies reduced production cost. Moreover, older farmers who have plenty of free time, can fully provide good care for chickens. Raising native chickens also helps in improving the health of older people, and reduced their depression and loneliness. However, raising chickens for commerce differs from backyard raising chickens. It requires more cost for constructing standard chicken houses as well as feeding system and vaccination. This case study shows that farmers who are members of community enterprise can obtain some assistance from government project. For example, the farmers under the native chicken bank project of Phayao Province have obtained academic drives from government sectors that include university, Department of Livestock Development which provide knowledge about raising chickens as well as materials such as standard incubator, vaccination management. These forms of support enable farmers to supply chickens to the market all-year round and improve quality which leads to marketing confidence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our gratitude to the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) for providing funding for this research study. We also would like to thank the Community Enterprises in Phayao Province for providing information and good cooperation in our field work. Finally, we would like to express our sincere thanks to Maejo University - Phrae Campus for allowing us to work on this research study.

REFERENCES

Adoligbe, C. et al. (2020). Native chicken farming: A tool for wealth creation and food security in Benin. International Journal of Livestock Production, 11(4): 146-162.

Apisada Lao Wattanapong. (2011). Needs and give direction to the social welfare policy among elderly people in the Bangkok Metropolitan area. Academic Services Journal, Prince of Songkla University, 22(3): 56-67.

Bank of Thailand (BOT). (2022). Exchange rate at Jan-Dec 2021. Retrived August, from Bank of Thailand: https://www.bot.or.th/App/BTWS_STAT/statistics/ReportPage.aspx?reportID=...

Bunyat Loaphaibool and Monchai Duangjinda. (2012). Native chicken: Past Present and Future. KHON KAEN AGR. J., 40: 309-312.

Chetsanee Chantawong. (2018). Career development of elderly in Thailand. In the preceding on conference ASEAN on the Path of Community. 3 December 2018 at Faculty of Political Science, Ramkhamhaeng University.

Department of Mental Health. (2020). Forward aged society in Thailand. Retrived February, from Department of Mental Health: https://www.dmh.go.th/news-dmh/view.asp?id=30476

Ketsara Phoyen. (2019). Aging Society: Opportunities for the Future Sustainable Business. Journal of Management Science Review, 21(1): 201-209.

Nalinee Kongsuban, Worasin Malaithong, Anugul Junkaew and Teeka Yotapakdee. (2018). Factors Influencing Consumer Purchasing Decision of Safety Pradu-Hangdum Chicken in Phrae Province. KHON KAEN AGR. J., 46(4): 675-686.

Preeyanan Prasertia. (2015). Management learning communities to engage in honest livelihood tambon Donyhoen ChengYern district, Mahasarakham province. Master degree of Educational Program, Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University.

Patcharapong Chuanchom, Thirawat Chantuk, and Phitak Siriwong. (2018). Job styles for older workers. VRU Research and Development Journal Science and Technology, 13(1): 107-116.

Teeka Yotapakdee, Nalinee Kongsubun, Worasin Malithong and Savichaya Supaudomlerk Trirat. (2015). Opportunity of Free-range Native Chickens for Rural Enterprise Development in Phrae Province. KAEN AGR. J., 43(Supplement 2, 2015), 63-66.

Thai Health Promotion Foundation. (2021). Awareness aged society and highly expenses. Retrived February, from Thai Health Promotion Foundation: https://resourcecenter.thaihealth.or.th/article

Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI). (2012). Aged society project and budget. Office of Promotion and Protection of Children, Youth, the Elderly and Vulnerable Groups.

[1] average exchange rate (Jan-Dec 2021) 1 USD=32.01 THB (BOT, 2022)