ABSTRACT

The efficient tenure system and tenure security will lead to the productive use of lands which will ultimately foster increase in productivity. Therefore, this study analyzes the overview of this concept and its application in Myanmar’s context of identifying the rationales and providing recommendations. Tenure security is necessary for the incentives and the ability to farm intensively but nevertheless, it alone will not always lead to the more productive use of lands. In this context, efficient land market is necessary to allocate lands to the most effective users and to provide land with collateral value. The Farmland Law and the Virgin, Vacant and Fallow Land Management Law enacted in 2012 mainly influence the land tenure system in Myanmar. Land markets are mostly informal throughout the country. Most of them are share-contract types and usually among people with close relations. These types of land markets are less likely to bring efficiency-enhancing land transactions. Therefore, lands are less likely to be allocated to the best users and to have collateral value to access loans to invest in farming. Therefore, in Myanmar, for the more productive use of land, tenure should be more secure, and the land market needs to be more formal and efficient. First, the government needs to strengthen the laws and legislations to clearly assign and regulate property rights. Second, incorporating with development agencies, the government needs to provide a sound environment to facilitate the function of land market.

Keywords- Land tenure, land market, allocative efficiency, land policies

INTRODUCTION

Research rationale

Myanmar is a Southeast Asian country with non-negligible agricultural potential. In 2018, the country’s agricultural sector contributed by 30% of the GDP and provided about 56% of employment. The government has acknowledged agriculture development as a way to achieve sustainable development goal of reducing poverty and in 2018, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI) proposed the “5 Years Myanmar Agriculture Development Strategy and Investment Plan” to intervene rural development and increase national economy growth (Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Irrigation, 2018). Within this 5-Year plan, increasing productivity, good governance and competitiveness are seen as the main strategies to increase national food security and economy.

Intensive farming and productive use of lands are the necessary behaviors of farmers at the initial stage of increasing productivity. In this context, Feder, Onchan, and Chalamwong (1988) identified the relationship between efficiency in land use and land tenure stating that the efficient tenure system will lead to the productive use of lands which will ultimately foster increase in productivity. Therefore, it is important to analyze the concepts behind why and how the land tenure system has influences over productive use of land thereby, providing possible approaches to increase the extent of productive land-use to reach the goal of increasing productivity.

Research objectives

The first objective of this study is to analyze the concepts and implications of tenure security for the productive use of lands. Secondly, to apply these concepts to identify whether the existing tenure system in Myanmar has any significant influence upon productive use of lands. Finally, based on the results from the analysis, to provide recommendations to increase the extent of productive use of land in Myanmar.

ANALYSIS OF THE THEORIES AND CONCEPTS

Tenure system

Tenure system is the institutional arrangement for land that defines, allocates and regulates the property rights to land. As stated above, institutions may either be formal which is governed by law or informal which consists of conventions and code of behaviors. In terms of land tenure, the latter informal institutional arrangement is often regarded as customary tenure system. It usually contains a set of rules and regulations for property rights, which have been practiced through time by a community to manage their lands sustainably (FAO, 2002). These rules and regulations have become institutionalized for customary tenure system but they do not form part of statutory property rights system.

Roth and Haase (1998) pointed out that there are two related dimensions in the tenure system namely: property right definition and distribution. Definition refers to the security of land rights associated with tenure ownership and distribution refers to the type of owners who are entitled to receive these land rights. According to Dube and Guveya (2013), land tenure system includes static and dynamics components. Static refers to the applications for land administration and dynamic refers to the applications for land developments and reform processes.

Many researchers have pointed out the different tenure systems existing in different countries. According to Ncube (2018), some of the common tenure systems in effect over the world include but are not limited to the following: freehold, delayed freehold, registered leasehold, public rental, private rental, customary ownership, shared equity, shared ownership, Co-operative Tenure and Community Land Trusts (CLTS), non-formal tenure systems and religious tenure systems. These various types of tenure systems can be secure or insecure depending on the social, legal and administrative institutions of a given society.

Definition of tenure security

Feder et al. (1988) stated that ownership titles are synonymous with ownership security. However, Roth, Barrows, Carter, and Kanel (1989) argued that high level of tenure insecurity can exist even with the legal possession of land title and tenure security cannot be captured with the simple dichotomy between untitled and titled ownership. Kille and Lyne (1993) added that without efficient legal environment, registration of title-deeds served only to create confusion over property rights and reduced security of tenure. Therefore, tenure insecurity may exist even with legal ownership in situation where the authority lacks the incentive and ability to enforce these property rights. Tenure security in fact has a wide range of interpretations and therefore, it cannot be assumed by a simple variation between conventional and legal ownership. The owners should have the right to use, transfer, trade and subdivide their lands and the authority should have the rights and incentives to set rules and policies, to provide certainty, to enforce them and settle disputes. Tenure insecurity is likely to result if one of these is lacking.

Place, Roth, and Hazell (1994, p. 19) define tenure security as “the individual's perception of his/her rights to a piece of land on a continuous basis, free from imposition or interference from outside sources, as well as his/her ability to acquire the benefits of labor and capital invested in that land either in use or upon transfer to another holder. ” This definition includes three components: breadth; duration and assurance. The two former components imply definition and the latter implies enforcement of property rights.

Breadth refers to the quantity and scope of property rights contained in the tenure system. These generally include the rights to use, exclude and transfer. Duration of rights refers to the length of time or season during which a given right is legally validated. The length of time should be sufficiently long enough so that the landholders have the ability and confidence to recover the income stream generated by the investment. Therefore, the longevity of the aforementioned bundle of rights is important component of tenure security. Assurance refers to the legal, institutional and administrative provisions to recognize, guarantee and enforce the bundles of property rights and their durations. Landowners must feel confident that the prevailing legal system will uphold and enforce their land rights by protecting against the unlawful act of others and the result of such legal actions are easily forecasted. Even if the use rights and their durations are formally recorded in the customary or state laws, tenure is insecure if the assurance is lacking to provide certainty and compliance with these laws and to enforce property rights.

Tenure security and productive use of land

Nieuwoudt (1990) stated that the efficiency of land use firstly depends on the economic incentives to make investment, improvement and conservation in agriculture. Secondly, it depends on the ability to finance such investments and finally, the existence of efficient land market to allocate lands to the most effective users. In fact, these conditions are interrelated and dependent on each other.

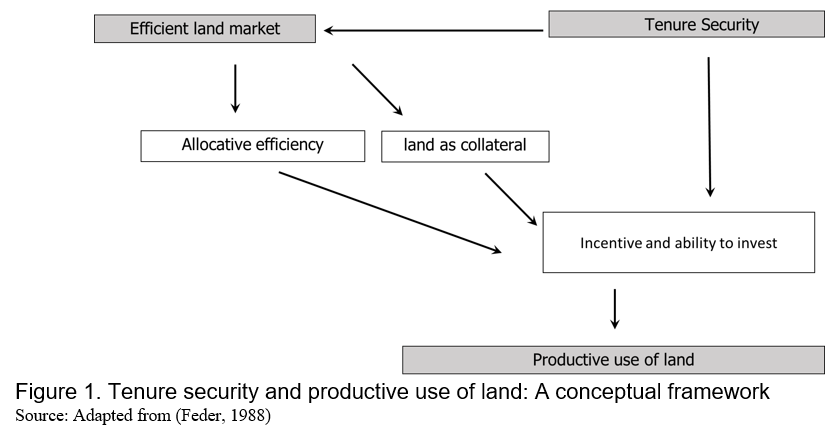

Figure 1 shows the relationship between tenure security, land market and productive use of land. The increase in tenure security facilitates the efficiency of land market. Efficient land market will increase allocative efficiency to shift lands to the more effective users and will provide lands with collateral value to access credit. Together with tenure security, these will increase incentive and ability to make investment for the productive use of land. According to Feder and Noronha (1987), the extent to which these conditions are met depends on the degree of tenure security shaped by the institutional environment within which the farmers operate.

LAND MARKET AND PRODUCTIVE USE OF LAND

Allocative efficiency

Deininger and Feder (2001) stated that in a situation in which individuals have differences in skills and endowments of production factors, market should help in optimizing such differences and increase efficiency by resource allocation. Therefore, with the well-functioned land market, the efficiency and equity enhancing land transfer could occur which offers benefits to both lessor and lessees.

An efficient land market will impose opportunity costs in the form of rents as farmers who own under-utilized lands may prefer to involve in the market than for missing out additional income (Dengu & Lyne, 2007). Allocative efficiency therefore improves by shifting lands from farmers who are either unwilling or unable to farm intensively to those who have the ability and incentives for intensive farming (Lyne & Nieuwoudt, 1991) as cited in (Dengu & Lyne, 2007). This improves farming efficiency by allowing farmers who are in need of land for massive farming purposes by accumulating lands, thereby reducing losses associated with fragmentation (Van Hung, MacAulay, & Marsh, 2007), unit transaction costs and benefiting from economies of scale (Kille & Lyne, 1993; Swinnen, Vranken, & Stanley, 2006).

Investment incentives

The land market, including rental contracts, will incentivize the landowners to make investments even when they have the short planning horizon as the benefits can be captured at any time through transacting lands as the current market value depends upon its expected productivity (Kille & Lyne, 1993). However, the tenants have lower incentives compared with the landowners owing to risks such as moral hazards (Binswanger et al., 1995). Therefore, the rental market might not increase efficiency in land use if the tenants lack the incentives to invest in land improvements or to apply sufficient inputs. For these reasons, Kille and Lyne (1993) stated that in terms of investment incentives, renting is the second best solution than selling.

Credit access

Land has traditionally been an ideal collateral asset where land is regarded as the scarce resource (Binswanger & Rosenzweig, 1986) as cited in (Feder, Lau, Lin, & Luo, 1990). However, collateral itself may be valuable only where there is land market that put value (Bruce & Dorner, 1982). Roth et al. (1989) described that two conditions such as the existence of land market and the feasibility of foreclosure are necessary for land to have collateral value. Lenders will be more likely to borrow only if the land has the collateral value and if the land market involves active land transactions for foreclosed land to be disposed of fairly easily. Increase in collateral value can increase the number of profitable lending opportunities and therefore better access to credit, increasing the landowners’ ability to make investment in farming. Kille and Lyne (1993) stated that the absence of sale market will not necessarily preclude the land use as collateral if there is rental market. According to Kerr (2004, pp. 290-291), the lessee with the consent of lessor is entitled to assign a lease to a third party. Therefore, with unique terms and conditions, the lease will be able to be used as collateral.

APPLICATIONS IN MYANMAR

Agricultural land in Myanmar

Myanmar has three main agro-ecological zones which have different land-use practices: the dry central zone focuses on livestock, crops and vegetable production, the lowland zone focuses on fisheries and rice production and the upland mountainous zone produces irrigated rice and rotational farming is practiced. In Myanmar, people’s relationship with their lands goes beyond economic interests and often involve a deep social security, cultural and spiritual connection (Franco, Twomey, Ju, Vervest, & Kramer, 2015). In 2012, The Farmland Law and The Vacant, Fallow and Virgin (VFV) Land Management Law were enacted in Myanmar.

Farmland Law and tenure security

The Farmland Law (2012) offers the landowners the exclusive ownership with the issuance of –Land Use Certificates-LUCs, where the use rights are freely transferable. The Law stipulates that the lands can be transacted on a land market with LUCs while transactions should be properly registered. Scurrah, Hirsch, & Woods, 2015 stated that the delivery of LUCs in the central and lowland zones have been comprehensive and efficient attributed to the existing land tenure systems developed in the colonial era. In these areas, the registration through LUCs have offered a certain degree of tenure security.

Myanmar has different types of customary tenure system which vary upon history, geography, resource base and ethnicity etc. Customary tenure system is mostly typical in Upland Zone of the country which represent 30-40% of the total land areas (Andersen, 2015). Agricultural land with rotational fallow farming and shifting cultivation is often considered as common property in upland communities (Srivinas & Hlaing, 2015). Such customary tenure system is maintained at the community level to govern themselves and have not been under the direct administration of the state. Importantly, during the colonial era, many ethnic communities in the upland zone gained autonomous status and enjoyed the de facto recognition of their customary tenure system (Food Security Working Group, 2011; Mark, 2016). This created an important issue in the modern era when the new Farmland law comes into effect in 2012, which brings the issuance of LUCs. The law challenges the de jure recognition of their customary tenure systems (von der Mühlen, 2018).

The law fails to recognize the customary tenure systems for most common property such as forest lands and lands use for grazing. Importantly, it fails to recognize shifting or swidden cultivations under farmland categories and, immediately labelled these areas as “wastelands” (Andersen, 2016; Boutry et al., 2017). Therefore, there has been serious political and civil conflicts in issuing LUCs for such shifting agricultural practices and people in the areas are lack of recognized statutory use rights. Ethnic upland communities are therefore under the real threat of losing their lands due to their lack of LUCs. Such lack of property rights to lands and tenure insecurity stresses the productive swidden and shifting cultivation in the uplands of Myanmar (Springate-Baginski, 2017).

VFV Law and tenure security

Despite the efforts to strengthen the tenure security with exclusive ownership through land titling system with LUCs, the VFV law poses the risks that undermine the degree of tenure security (Boutry et al., 2017). The VFV laws allow private sectors to obtain LUCs through land purchased or acquired by means of the government granting under the name of “vacant land” or “waste land”. VFV Law (2012) fails to recognize fallow lands used for shifting cultivation, considering them to be ‘vacant’, which leads to mis-classifications without due process, incorrect allocations and dispossession without prior consultation (Mark, 2016). Because of the absence of proper definition of VFV lands, the active fallow lands under rotation cycles can be legally declared as vacant and allocated to others (Scurrah et al., 2015). Such situation puts the landowners under the risk of losing their private and common property lands as their lands can be mistakenly labelled.

If this occurs, there is no formal independent mechanism to resolve conflicts (Tech, 2016). In addition, in most of these cases, the compensations are usually not satisfactory for the farmers (Mark, 2016). Tun, Kennedy, and Nischan (2015) stated that land confiscators were motivated by the growing value of land and have been able to use this VFV law to legitimize their actions, while further criminalizing smallholder farmers. Therefore, in the regions where there are lack of LUCs to claim exclusive ownership, VFV laws accelerate higher degree of tenure insecurity.

A report by DFID and FCO in 2013 as cited in (Henley, 2014) stated that several complaints to land administration committees for land grabbing and dispossessions were not less than 4,000 in number. In the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom with respect to Property Right, Myanmar stood in lower position compared with neighbouring countries (Kim & Holmes, 2016). The index is based on issues such as the performance of land titling, protection of private property and the independence of the legislature and judiciary. Therefore, lack of strong judiciary system to protect and enforce property rights is a cause of concern for tenure security in Myanmar.

Evidence of land market in Myanmar

According to the data from Hein, Lambrecht, Lwin, & Belton, 2017, in the country, most agricultural lands are owner-operated: 88% in upland and 91% in lowland parcels. The access to lands other than ownership are rare, with lease, shared and mortgaged accounting for only 3.4% of all land parcels operated in the central Myanmar. The data for land rental market in the country is very limited.

Srivinas and Hlaing (2015) found that in many rural areas, there is a growing trend of informal land market with higher land prices which offers the landowners with immediate high amount of cash. This situation entices small and marginal landowners to sell their lands and large landowners to sub-divide and sell a portion of their lands. Based on Agricultural Census 2010, they suggested that the reverse of landowners buying new lands and expanding their existing landholdings may not be occurring. This may be due to the difference between land prices and the net income stream from farming. Binswanger, Deininger, and Feder (1993) stated that if the difference is higher, the farmers will be more reluctant to buy lands and therefore voluntary transactions in sales are less likely to result in increased advantages.

The enactment of the new Farmland Law and the registration of LUCs are expected to strengthen the ownership property rights. LUCs offer transferable rights and are expected to facilitate efficient land market. However, the legal status of tenure has been insecure given the risks of land grabbing or VFM classification system (Baver et al., 2013; McCarthy, 2016; Srivinas & Hlaing, 2015). Despite such tenure insecurity, different forms of informal land transactions have been found out throughout the country.

According to Boutry et al. (2017), sharecropping is the common form of renting which is practiced throughout the country. They are usually made on a seasonal or annual basis. The landowners usually receive the proportion of the harvested produce or cash and receive half of the payment if they wish to obtain the rent ex-ante. Depending on the contractual arrangements, the proportion of the produce may vary from one-third to half. The scarcity of available lands strengthens the landowner’s bargaining power and let them to set the rental conditions and beneficial arrangements for them.

However, Hein et al. (2017) found that the land mortgage arrangement is more popular than sharecropping. In this form, the creditor obtains the land as a pledge for a loan given to the landowner. The creditor gets a temporary land use rights against a loan of a fixed amount and duration is usually several years and the price is usually two-thirds or half of land sale market price. Creditors can be landowners who are seeking to acquire land or landless entrepreneurs who are being unable to buy land at high prices.

There have been limited findings about fixed-rent type of contracting within the country. However, in recent years, mostly in the central part of the country, the landowners are making renting agreement with foreign investors to grow vegetables (Boutry et al., 2017). The agreements are usually fixed-rent, short-term with small-scale farmers. Srivinas and Hlaing (2015) stated that this practice is considered as illegal as the Farmland Law (2012) restrict transferring the use rights to foreigners without permission from the government. Despite this limitation, Antonio (2015) found out that within rental agreements between Chinese investors and local landowners in watermelon cultivations in the central zone, the landowners lease out their lands because of lower investment capacity and the uncertainty of climatic variations.

IMPACTS OF LAND TENURE SYSTEM ON THE PRODUCTIVE USE OF LAND

Impacts of land policies and tenure security

Jepsen, Palm, and Bruun (2019) pointed out that the uncertainty about tenure security in the upland zone because of the lack of statutory use rights is one of the factors that hampers the agricultural intensification. In recent years, there has been serious conflicts between large-scale land acquisition by private sectors and the dispossession of private property or common pool resource by smallholders (Willis, 2013). Mark (2016) found that there have been many discriminatory claiming of the private property or the common pool resources as VFV lands. This may stem from the lack of transparent recognition of existing rights to use the lands for a variety of purposes such as grazing, swiddening, fallowing and shifting cultivations and the poor identification of allocated lands in the VFV and Farmland Laws.

The “30 year Master Plan for the Agriculture Sector” launched in 2000 aimed to convert about 4 million hectares of what is defined as VFV lands into productive lands under private agribusiness (Chao, 2013). Such large-scale agricultural model has been promoted in Myanmar for agricultural development and the government has granted 1,568,547 hectares of VFV land for agriculture purposes (Henley, 2014). This poses a serious question regarding the efficiency of productive use of these granted lands. Thein, Diepart, Moe, and Allaverdian (2018) stated that only 14.89% of the VFV lands granted have actually been cultivated and the rest are left idle. He found out that in some companies, these lands are used as a pretext of agriculture to actually engage in other form of businesses. The rationales for the absence of land rental market for these underutilized VFV lands have not been widely known. According to Deininger and Feder (2001), the large landowners in some countries are reluctant to engage with multiple tenants due to concern for potential challenges to their property rights. The same situation might apply in Myanmar where there are weak tenure security, inefficient legal system, existing conflicts between the local smallholders and the large private businesses for these granted VFV lands. The other reason may be associated with the VFV laws which stated that the granted land use rights under VFV legislations do not contain the right to transfer or subdivide without permission from the government. This poses high unit transaction costs to register and obtain approval from the government for leasing out these lands. Such high transaction cost will attribute to the absence of land rental market for these underutilized granted VFV lands.

Impacts of land market

In Myanmar, most farm-households value their lands as a form of social security and therefore, the existence of rental market is a more reliable indicator of allocative efficiency than sale (Lyne et al., 1997). Renting facilitates productive use of land by transferring land to farmers who can use it more effectively. Deininger and Feder (2001) stated that in situations where the tenants have difficulties in accessing credits to pay up-front and the opportunities of risk-sharing against fluctuations in output, the share contract types are in favor than fixed-rent. This statement is applicable to the popularity of sharecropping in Myanmar where the farmers are facing difficulties in accessing affordable credits for investment, uncertainty of weather and market price for products (Boutry et al., 2 017).

However, Deininger and Feder (2001) also stated that under conditions of weakened enforceability of contracts, any type of contract other than fixed-rent would result in underinvestment of tenants. This is because with other types of contracts, tenants receive only a fraction of their marginal product which would incentivize them to exert less efforts and investment. Therefore, the share contract type of rental market may lead to the allocative efficiency but if the contracts are not strongly enforceable, the lands will not result in intensive use.

In addition, Boutry et al. (2017) found that the sharecropping type of renting in the country is usually among the family, neighbors and friends. Sadoulet, De Janvry, and Fukui (1997) stated that the extent of productive use of land depends on the relationship between the contractual parties. They found that the investments in input usage are higher in sharecropping between the close-kin than with non-kin. This may be associated with high ex-ante transaction costs of searching and negotiating with new contractual partner and the high ex-post transaction costs of enforcing the contracts in case of moral hazard. If the sharecropping is mostly between the close-kin because of high transaction costs, the lands will be less likely to be allocated to the most effective users. The seasonal fixed-renting contracts with foreign investors and mortgage arrangements are not necessarily personalized but sometimes, they are not mutually beneficial. In both of these cases, there are usually power asymmetry between the parties in terms of credit, bargaining power and market information (Boutry et al., 2017). Antonio (2015) found that because of the investment constraints, the landowners in the central Myanmar are subjected to distress renting even when the contracts are not satisfactorily winning in their favor, especially in terms of profitability. Therefore, this poses serious question regarding the effectiveness and productive use of lands whether by the landowners or the tenants under such tenancy arrangements.

Prior to the enactment of the Farmland Law (2012), land cannot be used as collateral to access credit. After issuance of LUCs, the Farmland Law allows banks to accept land as collateral for loans using LUCs. In this context these financial institutions should, theoretically, be able to expand finance for farmers to make investment for productive farming. However, Kirk and Tuan (2009) indicated the evidence in Vietnam where banks are still reluctant to accept land-use certificates as collateral due to the perceived difficulty of seizing land to cover loan defaults. Similarly, Myanmar still have poor legislations and lack of transparent strong legal procedure for the event of foreclosure (Tun et al., 2015) which would make the banks hesitate to offer loan products to farmers. However, evidence in aquaculture research by Boughton et al. (2015) indicated that LUCs are being used as the collateral to access credit but most of them are limited under certain authorized banks. Nevertheless, because of the increasing land grabbing by large agribusinesses and increase in land market value, the farmers who have exclusive ownership with LUCs are expected to have the ability to access credit from upcoming financial institutions.

CONCLUSION

This research intends to analyze how the institutional arrangements for land, in other words, how the tenure system influences the behavior of farmers in productive use of lands. The following section concludes the implications of the land tenure system especially tenure security and land market for the productive use of lands and applications of these concepts in Myanmar.

An efficient land market will impose opportunity costs to farmers who owns underutilized lands. Allocative efficiency therefore improves by shifting lands to the more effective users who can use them more productively. This improves farming efficiency by allowing farmers who are in need of lands for massive farming purposes to reduce unit transaction costs and to benefit from economy of scale. Land market will provide the land with the collateral value to access credit from financial institutions to make investment. In these ways, land market increases the ability and incentive of farmers to use the lands productively.

Myanmar is a Southeast Asia country where agriculture is the main industry, accounting for 22% of the GDP (Agricultureat a Glance 2020, DOP) and employing about 65% of the labor force. Historically, during the military regime (1962–2011), the land rights were under strict control on crop choices and marketing of produce was enforced. However, recent political and economic developments within the country have driven changes to the state land management system. In 2012, the Myanmar government introduced the Farmland Law and the Vacant Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law) which significantly altered how agricultural land is managed.

The Farmland Law allows landowners to have exclusive ownership through the issuance of Land Use Certificates (LUCs) which are transferable and marketable. This land titling system has been effective in the central and lowland zones of the country. However, it fails to recognize communal land ownership in the upland zone where the farmers practice shifting cultivations. The law does not recognize shifting cultivations under farmland categories and labels these cultivation areas as waste lands. Therefore, most landowners in the upland zone are lack of statutory ownership.

The VFV law allows farmers and private investors to apply and obtain vacant, fallow and virgin lands. However, it does not contain transparent due procedure in defining the VFV lands to be granted to the applicants and in some cases, misclassifies the common property or private property as vacant. Therefore, most landowners who lack legal ownership, usually those under customary tenure, are under the threat of losing their lands. By 2017, the government has granted nearly 4 million hectares of VFV lands, however, only 14% are under cultivation and the rest are left idle.

Most land market transactions in Myanmar are informal and usually among people with close relations. Sharecropping and mortgage arrangements are the common forms of access to lands apart from ownership. Fixed-rent types are rare throughout the country and the expected reasons may be due to the inability to access credit to pay upfront and due to the prospect of risk-sharing. However, Deininger and Feder (2001) have pointed out that farmers will not have strong incentives to exert efforts and make investment in case of share-rent as they receive only a fraction of their marginal product.

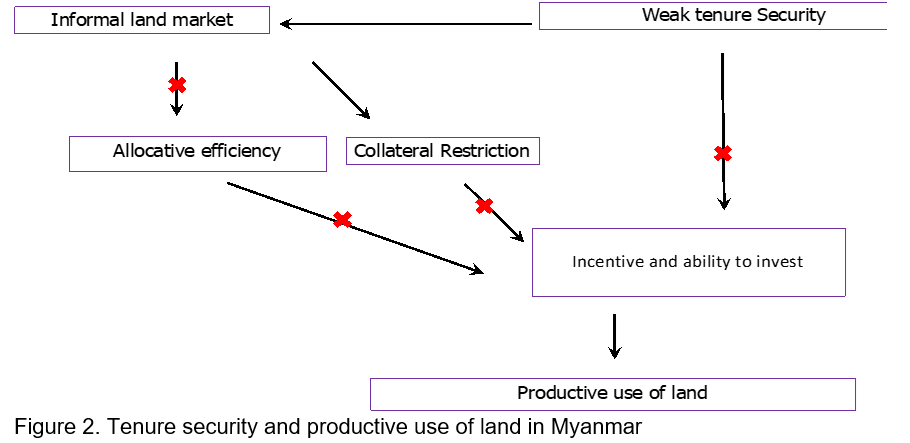

Figure 2 shows the summary of implications for Myanmar land tenure system and its impacts on productive use of lands. Landowners may not have incentives to make investment for the productive use of lands under weak tenure security. Such tenure insecurity combined with high transaction costs hinder the efficiency of land market. If the land market is not functioning efficiently, the land will not be allocated to the most effective farmers who will farm more productively. Due to the remaining concern about tenure security and the function of land market, farmers are facing challenges to access credit using the land as collateral. Therefore, farmers will have difficulties to make investment for productive farming.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the analysis, in Myanmar, for the more productive use of land, “tenure should be more secure, and the land rental market needs to be more formal and efficient.” The government needs to strengthen the laws and legislations to clearly assign and regulate property rights. It is important to ensure that these rights contain appropriate bundle of rights that are definite, durable and has assurance. It is important to understand that the sore focus of a particular tenure system should be the security, appropriateness and ability to facilitate the need of the society instead of being right or wrong and good or bad system. The followings are the recommendations for the government but not limited to:

- Resolve the current land conflicts and complaints between the farmers;

- Secure the existing titled lands;

- Allow and facilitate the issuance of LUCs for community or a group as a whole to recognize, register and document their customary tenure system;

- The Farmland law needs to make amendments to broaden the entitlement of “farmland” to include the lands held under agro-forestry, grazing, shifting cultivation systems which are managed under customary tenure system; and

- The VFV lands law need to make amendments to specify the terms and conditions for categorizing VFV lands.

The formation, efficiency and sustainability of the land rental market largely depend on the government intervention and commitments. The following approaches are the required preconditions for the development of efficient land rental market adapted from the strategies described by Thomson, 1996.

Willing lessors and lessees need to be identified and the lists should be publicized to reduce fixed ex-ante transaction costs of searching information. Rental transactions need to be recorded in the written lease contracts. The local authority needs to endorse and uphold these contracts, set up transparent legal system including dispute procedures to reduce variable ex-post transaction costs of enforcing the contracts and settling disputes. Imposing taxes for rental transactions would incentivize them and cover the costs for administering the contracts.

The information of market, the property rights, negotiations between rights and obligations of contractual parties, list of willing lessors and lessees, and dispute procedures should be disseminated through trainings or meetings. If necessary, the development agencies should provide capacity building and act as a mediator between the farmers and the authorities to facilitate the rental market.

REFERENCES

Andersen, K. E. (2015). Analysis of Customary Communal Tenure of Upland Ethnic Groups, Myanmar. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Burma/Myanmar Studies (pp. 24-26). Chiang Mai, Thailand

Andersen, K. E. (2016). Institutional Models for a Future Recognition and Registration of Customary (Communal) Tenure in Myanmar. In Proceedings of the 2016 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty (pp. 14-18). Washington DC, USA

Antonio, M. E. R. (2015). Patterns of access to land by Chinese agricultural investors and their impacts on rural households in Mandalay Region, Myanmar. University of Hohenheim.

Bardhan, P. (1987). Alternative approaches to the theory of institutions in economic development. In The Economic Theory of Agrarian Institutions: Oxford University Press, New York.

Baver, J., Jonveaux, B., Ju, R., Kitamura, K., Sharma, P., Wade, L., & Yasui, S. (2013). Securing livelihoods and land tenure in rural Myanmar. UN-Habitat and Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs.

Binswanger, H. P., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (1986). Behavioural and material determinants of production relations in agriculture. The Journal of Development Studies, 22(3), 503-539.

Binswanger, H. P., Deininger, K., & Feder, G. (1993). Agricultural land relations in the developing world. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 75(5), 1242-1248.

Binswanger, H. P., Deininger, K., & Feder, G. (1995). Power, distortions, revolt and reform in agricultural land relations. Handbook of Development Economics, 3, 2659-2772.

Boughton, D., Htoo, K., Kham, L. S., Reardon, T., Hein, A., Belton, B., & Nischan, U. (2015). Aquaculture in Transition: Value Chain Transformation, Fish and Food Security in Myanmar. Retrieved from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/259027/

Boutry, M., Allaverdian, C., Mellac, M., Huard, S., Thein, S., Win, T. M., & Sone, K. (2017). Land tenure in rural lowland Myanmar: From historical perspectives to contemporary realities in the Dry zone and the Delta. Retrieved from https://www.gret.org/wp-content/uploads/GRET_LandTenure_PDF_86844-319-9.pdf

Bruce, J. W., & Dorner, P. P. (1982). Agricultural land tenure in Zambia: Perspectives, problems, and opportunities. Wisconsin, U.S.A: Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Bruce, J. W., & Freudenberger, M. S. (1992). Institutional Constraints and Opportunities in African Land Tenure: Shifting from a" replacement" to an" adaptation" Paradigm. Wisconsin, U.S.A: Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Bryant, R. L. (1996). The greening of Burma: political rhetoric or sustainable development? Pacific Affairs, 341-359.

Chao, S. (2013). Agribusiness Large-scale Land Acquisitions and Human Rights in Southeast Asia: Updates from Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Cambodia, Timor-Leste and Burma, August 2013: Retrieved from https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/topics/agribusiness/publication/2013/agribusiness-large-scale-land-acquisitions-and-human-rights-sou

Dengu, T., & Lyne, M. C. (2007). Secure land rental contracts and agricultural investment in two communal areas of KwaZulu-Natal. Agrekon, 46(3), 398-409.

Deininger, K., & Feder, G. (2001). Land institutions and land markets. Handbook of Agricultural Economics, 1, 287-331.

DOP, 2020. Agricultureat a Glance 2020. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Myanmar.

Dube, L., & Guveya, E. (2013). Land tenure security and farm investments amongst small scale commercial farmers in Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 15(5), 107-121.

Ennion, J. D. (2015). From Conflicting to Complementing: The Formalisation of Customary Land Management Systems Governing Swidden Cultivation in Myanmar. Victoria University of Wellington.

FAO. (2002). Land tenure and rural development. In FAO Land Tenure Studies (3 ed.). Rome

Feder, G. (1988). Land policies and farm productivity in Thailand. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Feder, G., Lau, L. J., Lin, J. Y., & Luo, X. (1990). The relationship between credit and productivity in Chinese agriculture: A microeconomic model of disequilibrium. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 72(5), 1151-1157.

Feder, G., & Noronha, R. (1987). Land rights systems and agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa. The World Bank Research Observer, 2(2), 143-169.

Feder, G., Onchan, T., & Chalamwong, Y. (1988). Land policies and farm performance in Thailand's forest reserve areas. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 36(3), 483-501.

Food Security Working Group. (2011). Upland land tenure security in Myanmar: An overview: Author. Retrieved from https://www.burmalibrary.org/docs16/FSWG-Upland_Land_Tenure_Security-201...

Franco, J., Twomey, H., Ju, K. K., Vervest, P., & Kramer, T. (2015). The Meaning of Land in Myanmar. Transnational Institute Myanmar, 1-39.

Furnivall, J. S. (1957). An introduction to the political economy of Burma. Yangon, Myanmar: Peoples' Literature Committee & House.

Hein, A., Lambrecht, I., Lwin, K., & Belton, B. (2017). Agricultural Land in Myanmar’s Dry Zone. Retrieved from https://www.ifpri.org/cdmref/p15738coll2/id/132336/filename/132542.pdf

Henley, G. (2014). Case study on Land in Burma. Evidence on Demand: Overseas Development Instititue.

Huxley, A. (1995). Buddhism and law–The view from Mandalay. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 47-95.

Huxley, A. (1997). The importance of the Dhammathats in Burmese law and culture. Journal of Burma Studies, 1(1), 1-17.

Jepsen, M. R., Palm, M., & Bruun, T. B. (2019). What Awaits Myanmar’s Uplands Farmers? Lessons Learned from Mainland Southeast Asia. Land Cover/Land-Use Changes in South and Southeast Asia, 8(2), 29.

Kerr, A. J. (2004). The law of sale and lease (3 ed.). South Africa: LexisNexis Butterworths. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.nz/books/about/The_Law_of_Sale_and_Lease.html?id=HBJlAAAACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Kille, G., & Lyne, M. (1993). Investment on freehold and trust farms: Theory with some evidence from kwazulu/Beleggings op eienaar en Trust grond: Teorie met bewyse van KwaZulu. Agrekon, 32(3), 101-109.

Kim, A. B., & Holmes, K. R. (2016). 2014 Index of economic freedom. The Heritage Foundation in Partnership with Wall Street Journal.

Kirk, M., & Tuan, N. D. A. (2009). Land-tenure policy reforms: Decollectivization and the Doi Moi system in Vietnam: International Food Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/fpr/ifprid/927.html#download

Lyne, M., Troutt, B., & Roth, M. (1997). Land rental markets in sub-Saharan Africa: institutional change in customary tenure. In R. Rose, Tanner, C and Bellamy, M (Ed.), Issues in Agricultural Competitiveness: Markets and Policies (pp. 58-67). : Dartmouth Publishing Company, Aldershot.

Lyne, M., & Nieuwoudt, W. (1991). Inefficient land use in KwaZulu: Causes and remedies. Development Southern Africa, 8(2), 193-201.

Mark, S. (2016). Are the odds of justice “stacked” against them? Challenges and opportunities for securing land claims by smallholder farmers in Myanmar. Critical Asian Studies, 48(3), 443-460.

McCarthy, S. (2016). Land tenure security and policy tensions in Myanmar (Burma). AsiaPacific Issues(127).

McCarthy, S. (2018). Rule of law expedited: Land title reform and justice in Burma (Myanmar). Asian Studies Review, 42(2), 229-246.

Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Irrigation. (2018). Myanmar Agiculture Development Strategy and Investment Plan (2018-19~2022-23) Retrieved from https://www.lift-fund.org/sites/lift-fund.org/files/publication/MOALI_AD...

Nieuwoudt, W. (1990). Efficiency of land use/Doeltreffendheid van grondgebruik. Agrekon, 29(4), 210-215.

Place, F., Roth, M., & Hazell, P. (1994). Land tenure security and agricultural performance in Africa: Overview of research methodology. Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa, 15-39.

Roth, M., Barrows, R., Carter, M., & Kanel, D. (1989). Land ownership security and farm investment: Comment. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 71(1), 211-214.

Roth, M., & Haase, D. (1998). Land tenure security and agricultural performance in Southern Africa: Citeseer. Retrieved from Land tenure security and agricultural performance in Southern Africa

Swinnen, J., Vranken, L., & Stanley, V. (2006). Emerging challenges of land rental markets. Retrieved from http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2006/08/23/000090341_20060823150555/Rendered/PDF/369820Emerging0alMarkets0FullReport.pdf

Sadoulet, E., De Janvry, A., & Fukui, S. (1997). The meaning of kinship in sharecropping contracts. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(2), 394-406.

Scurrah, N., Hirsch, P., & Woods, K. (2015). The political economy of land governance in Myanmar. Mekong Region Land Governance and University of Sydney: Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic(27).

South, A. (2008). Displacement and dispossession: forced migration and land rights in Burma. Geneva, Switzerland: Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE).

Springate-Baginski, O. (2017). Rethinking swidden cultivation in Myanmar. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/71db/59ab0f8eb502c7c93fd487c88d43f9490a...

Srivinas, S., & Hlaing, U. S. (2015). Myanmar: Land Tenure Issues and the Impact on Rural Development: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs21/FAO-2015-05-Myanmar-land_tenure&rural...

Tech, T. (2016). Community land and resource tenure recognition: Review of country experiences. Retrieved from https://www.burmalibrary.org/docs21/USAID-2016-Myanmar_Community_Tenure_...

Thein, S., Diepart, J.-C., Moe, H., & Allaverdian, C. (2018). Large-scale land acquisitions for agricultural development in Myanmar: A review of past and current processes. Retrieved from https://www.mrlg.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/SanThein-etal_2018_LSLA-...

Thomson, D. N. (1996). A study of land rental markets and institutions in communal areas of rural KwaZulu-Natal. University of Natal Pietermaritzburg.

Tun, T., Kennedy, A., & Nischan, U. (2015). Promoting agricultural growth in Myanmar: A review of policies and an assessment of knowledge gaps. Retrieved from https://www.ifpri.org/cdmref/p15738coll2/id/129810/filename/130021.pdf

UN-Habitat. (2011). Guidance Note on Land Issues (Myanmar). Retrieved from https://www.burmalibrary.org/sites/burmalibrary.org/files/obl/docs12/Guidance_Note_on_Land_Issues-Myanmar.pdf

Van Hung, P., MacAulay, T. G., & Marsh, S. P. (2007). The economics of land fragmentation in the north of Vietnam. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 51(2), 195-211.

von der Mühlen, M. (2018). The fate of customary tenure systems of ethnic minority groups in upland Myanmar. Zürich, Switzerland: ETH Zürich, Centre for Development and Cooperation (NADEL).

Willis, N. (2013). Land disputes and the ongoing development of the substantive rule of law in Myanmar (Burma). International Journal of Public Law and Policy 4(4):321

Analysis of Implications of Agricultural Land Tenure System for Productive Use of Lands: Application in Myanmar

ABSTRACT

The efficient tenure system and tenure security will lead to the productive use of lands which will ultimately foster increase in productivity. Therefore, this study analyzes the overview of this concept and its application in Myanmar’s context of identifying the rationales and providing recommendations. Tenure security is necessary for the incentives and the ability to farm intensively but nevertheless, it alone will not always lead to the more productive use of lands. In this context, efficient land market is necessary to allocate lands to the most effective users and to provide land with collateral value. The Farmland Law and the Virgin, Vacant and Fallow Land Management Law enacted in 2012 mainly influence the land tenure system in Myanmar. Land markets are mostly informal throughout the country. Most of them are share-contract types and usually among people with close relations. These types of land markets are less likely to bring efficiency-enhancing land transactions. Therefore, lands are less likely to be allocated to the best users and to have collateral value to access loans to invest in farming. Therefore, in Myanmar, for the more productive use of land, tenure should be more secure, and the land market needs to be more formal and efficient. First, the government needs to strengthen the laws and legislations to clearly assign and regulate property rights. Second, incorporating with development agencies, the government needs to provide a sound environment to facilitate the function of land market.

Keywords- Land tenure, land market, allocative efficiency, land policies

INTRODUCTION

Research rationale

Myanmar is a Southeast Asian country with non-negligible agricultural potential. In 2018, the country’s agricultural sector contributed by 30% of the GDP and provided about 56% of employment. The government has acknowledged agriculture development as a way to achieve sustainable development goal of reducing poverty and in 2018, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI) proposed the “5 Years Myanmar Agriculture Development Strategy and Investment Plan” to intervene rural development and increase national economy growth (Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Irrigation, 2018). Within this 5-Year plan, increasing productivity, good governance and competitiveness are seen as the main strategies to increase national food security and economy.

Intensive farming and productive use of lands are the necessary behaviors of farmers at the initial stage of increasing productivity. In this context, Feder, Onchan, and Chalamwong (1988) identified the relationship between efficiency in land use and land tenure stating that the efficient tenure system will lead to the productive use of lands which will ultimately foster increase in productivity. Therefore, it is important to analyze the concepts behind why and how the land tenure system has influences over productive use of land thereby, providing possible approaches to increase the extent of productive land-use to reach the goal of increasing productivity.

Research objectives

The first objective of this study is to analyze the concepts and implications of tenure security for the productive use of lands. Secondly, to apply these concepts to identify whether the existing tenure system in Myanmar has any significant influence upon productive use of lands. Finally, based on the results from the analysis, to provide recommendations to increase the extent of productive use of land in Myanmar.

ANALYSIS OF THE THEORIES AND CONCEPTS

Tenure system

Tenure system is the institutional arrangement for land that defines, allocates and regulates the property rights to land. As stated above, institutions may either be formal which is governed by law or informal which consists of conventions and code of behaviors. In terms of land tenure, the latter informal institutional arrangement is often regarded as customary tenure system. It usually contains a set of rules and regulations for property rights, which have been practiced through time by a community to manage their lands sustainably (FAO, 2002). These rules and regulations have become institutionalized for customary tenure system but they do not form part of statutory property rights system.

Roth and Haase (1998) pointed out that there are two related dimensions in the tenure system namely: property right definition and distribution. Definition refers to the security of land rights associated with tenure ownership and distribution refers to the type of owners who are entitled to receive these land rights. According to Dube and Guveya (2013), land tenure system includes static and dynamics components. Static refers to the applications for land administration and dynamic refers to the applications for land developments and reform processes.

Many researchers have pointed out the different tenure systems existing in different countries. According to Ncube (2018), some of the common tenure systems in effect over the world include but are not limited to the following: freehold, delayed freehold, registered leasehold, public rental, private rental, customary ownership, shared equity, shared ownership, Co-operative Tenure and Community Land Trusts (CLTS), non-formal tenure systems and religious tenure systems. These various types of tenure systems can be secure or insecure depending on the social, legal and administrative institutions of a given society.

Definition of tenure security

Feder et al. (1988) stated that ownership titles are synonymous with ownership security. However, Roth, Barrows, Carter, and Kanel (1989) argued that high level of tenure insecurity can exist even with the legal possession of land title and tenure security cannot be captured with the simple dichotomy between untitled and titled ownership. Kille and Lyne (1993) added that without efficient legal environment, registration of title-deeds served only to create confusion over property rights and reduced security of tenure. Therefore, tenure insecurity may exist even with legal ownership in situation where the authority lacks the incentive and ability to enforce these property rights. Tenure security in fact has a wide range of interpretations and therefore, it cannot be assumed by a simple variation between conventional and legal ownership. The owners should have the right to use, transfer, trade and subdivide their lands and the authority should have the rights and incentives to set rules and policies, to provide certainty, to enforce them and settle disputes. Tenure insecurity is likely to result if one of these is lacking.

Place, Roth, and Hazell (1994, p. 19) define tenure security as “the individual's perception of his/her rights to a piece of land on a continuous basis, free from imposition or interference from outside sources, as well as his/her ability to acquire the benefits of labor and capital invested in that land either in use or upon transfer to another holder. ” This definition includes three components: breadth; duration and assurance. The two former components imply definition and the latter implies enforcement of property rights.

Breadth refers to the quantity and scope of property rights contained in the tenure system. These generally include the rights to use, exclude and transfer. Duration of rights refers to the length of time or season during which a given right is legally validated. The length of time should be sufficiently long enough so that the landholders have the ability and confidence to recover the income stream generated by the investment. Therefore, the longevity of the aforementioned bundle of rights is important component of tenure security. Assurance refers to the legal, institutional and administrative provisions to recognize, guarantee and enforce the bundles of property rights and their durations. Landowners must feel confident that the prevailing legal system will uphold and enforce their land rights by protecting against the unlawful act of others and the result of such legal actions are easily forecasted. Even if the use rights and their durations are formally recorded in the customary or state laws, tenure is insecure if the assurance is lacking to provide certainty and compliance with these laws and to enforce property rights.

Tenure security and productive use of land

Nieuwoudt (1990) stated that the efficiency of land use firstly depends on the economic incentives to make investment, improvement and conservation in agriculture. Secondly, it depends on the ability to finance such investments and finally, the existence of efficient land market to allocate lands to the most effective users. In fact, these conditions are interrelated and dependent on each other.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between tenure security, land market and productive use of land. The increase in tenure security facilitates the efficiency of land market. Efficient land market will increase allocative efficiency to shift lands to the more effective users and will provide lands with collateral value to access credit. Together with tenure security, these will increase incentive and ability to make investment for the productive use of land. According to Feder and Noronha (1987), the extent to which these conditions are met depends on the degree of tenure security shaped by the institutional environment within which the farmers operate.

LAND MARKET AND PRODUCTIVE USE OF LAND

Allocative efficiency

Deininger and Feder (2001) stated that in a situation in which individuals have differences in skills and endowments of production factors, market should help in optimizing such differences and increase efficiency by resource allocation. Therefore, with the well-functioned land market, the efficiency and equity enhancing land transfer could occur which offers benefits to both lessor and lessees.

An efficient land market will impose opportunity costs in the form of rents as farmers who own under-utilized lands may prefer to involve in the market than for missing out additional income (Dengu & Lyne, 2007). Allocative efficiency therefore improves by shifting lands from farmers who are either unwilling or unable to farm intensively to those who have the ability and incentives for intensive farming (Lyne & Nieuwoudt, 1991) as cited in (Dengu & Lyne, 2007). This improves farming efficiency by allowing farmers who are in need of land for massive farming purposes by accumulating lands, thereby reducing losses associated with fragmentation (Van Hung, MacAulay, & Marsh, 2007), unit transaction costs and benefiting from economies of scale (Kille & Lyne, 1993; Swinnen, Vranken, & Stanley, 2006).

Investment incentives

The land market, including rental contracts, will incentivize the landowners to make investments even when they have the short planning horizon as the benefits can be captured at any time through transacting lands as the current market value depends upon its expected productivity (Kille & Lyne, 1993). However, the tenants have lower incentives compared with the landowners owing to risks such as moral hazards (Binswanger et al., 1995). Therefore, the rental market might not increase efficiency in land use if the tenants lack the incentives to invest in land improvements or to apply sufficient inputs. For these reasons, Kille and Lyne (1993) stated that in terms of investment incentives, renting is the second best solution than selling.

Credit access

Land has traditionally been an ideal collateral asset where land is regarded as the scarce resource (Binswanger & Rosenzweig, 1986) as cited in (Feder, Lau, Lin, & Luo, 1990). However, collateral itself may be valuable only where there is land market that put value (Bruce & Dorner, 1982). Roth et al. (1989) described that two conditions such as the existence of land market and the feasibility of foreclosure are necessary for land to have collateral value. Lenders will be more likely to borrow only if the land has the collateral value and if the land market involves active land transactions for foreclosed land to be disposed of fairly easily. Increase in collateral value can increase the number of profitable lending opportunities and therefore better access to credit, increasing the landowners’ ability to make investment in farming. Kille and Lyne (1993) stated that the absence of sale market will not necessarily preclude the land use as collateral if there is rental market. According to Kerr (2004, pp. 290-291), the lessee with the consent of lessor is entitled to assign a lease to a third party. Therefore, with unique terms and conditions, the lease will be able to be used as collateral.

APPLICATIONS IN MYANMAR

Agricultural land in Myanmar

Myanmar has three main agro-ecological zones which have different land-use practices: the dry central zone focuses on livestock, crops and vegetable production, the lowland zone focuses on fisheries and rice production and the upland mountainous zone produces irrigated rice and rotational farming is practiced. In Myanmar, people’s relationship with their lands goes beyond economic interests and often involve a deep social security, cultural and spiritual connection (Franco, Twomey, Ju, Vervest, & Kramer, 2015). In 2012, The Farmland Law and The Vacant, Fallow and Virgin (VFV) Land Management Law were enacted in Myanmar.

Farmland Law and tenure security

The Farmland Law (2012) offers the landowners the exclusive ownership with the issuance of –Land Use Certificates-LUCs, where the use rights are freely transferable. The Law stipulates that the lands can be transacted on a land market with LUCs while transactions should be properly registered. Scurrah, Hirsch, & Woods, 2015 stated that the delivery of LUCs in the central and lowland zones have been comprehensive and efficient attributed to the existing land tenure systems developed in the colonial era. In these areas, the registration through LUCs have offered a certain degree of tenure security.

Myanmar has different types of customary tenure system which vary upon history, geography, resource base and ethnicity etc. Customary tenure system is mostly typical in Upland Zone of the country which represent 30-40% of the total land areas (Andersen, 2015). Agricultural land with rotational fallow farming and shifting cultivation is often considered as common property in upland communities (Srivinas & Hlaing, 2015). Such customary tenure system is maintained at the community level to govern themselves and have not been under the direct administration of the state. Importantly, during the colonial era, many ethnic communities in the upland zone gained autonomous status and enjoyed the de facto recognition of their customary tenure system (Food Security Working Group, 2011; Mark, 2016). This created an important issue in the modern era when the new Farmland law comes into effect in 2012, which brings the issuance of LUCs. The law challenges the de jure recognition of their customary tenure systems (von der Mühlen, 2018).

The law fails to recognize the customary tenure systems for most common property such as forest lands and lands use for grazing. Importantly, it fails to recognize shifting or swidden cultivations under farmland categories and, immediately labelled these areas as “wastelands” (Andersen, 2016; Boutry et al., 2017). Therefore, there has been serious political and civil conflicts in issuing LUCs for such shifting agricultural practices and people in the areas are lack of recognized statutory use rights. Ethnic upland communities are therefore under the real threat of losing their lands due to their lack of LUCs. Such lack of property rights to lands and tenure insecurity stresses the productive swidden and shifting cultivation in the uplands of Myanmar (Springate-Baginski, 2017).

VFV Law and tenure security

Despite the efforts to strengthen the tenure security with exclusive ownership through land titling system with LUCs, the VFV law poses the risks that undermine the degree of tenure security (Boutry et al., 2017). The VFV laws allow private sectors to obtain LUCs through land purchased or acquired by means of the government granting under the name of “vacant land” or “waste land”. VFV Law (2012) fails to recognize fallow lands used for shifting cultivation, considering them to be ‘vacant’, which leads to mis-classifications without due process, incorrect allocations and dispossession without prior consultation (Mark, 2016). Because of the absence of proper definition of VFV lands, the active fallow lands under rotation cycles can be legally declared as vacant and allocated to others (Scurrah et al., 2015). Such situation puts the landowners under the risk of losing their private and common property lands as their lands can be mistakenly labelled.

If this occurs, there is no formal independent mechanism to resolve conflicts (Tech, 2016). In addition, in most of these cases, the compensations are usually not satisfactory for the farmers (Mark, 2016). Tun, Kennedy, and Nischan (2015) stated that land confiscators were motivated by the growing value of land and have been able to use this VFV law to legitimize their actions, while further criminalizing smallholder farmers. Therefore, in the regions where there are lack of LUCs to claim exclusive ownership, VFV laws accelerate higher degree of tenure insecurity.

A report by DFID and FCO in 2013 as cited in (Henley, 2014) stated that several complaints to land administration committees for land grabbing and dispossessions were not less than 4,000 in number. In the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom with respect to Property Right, Myanmar stood in lower position compared with neighbouring countries (Kim & Holmes, 2016). The index is based on issues such as the performance of land titling, protection of private property and the independence of the legislature and judiciary. Therefore, lack of strong judiciary system to protect and enforce property rights is a cause of concern for tenure security in Myanmar.

Evidence of land market in Myanmar

According to the data from Hein, Lambrecht, Lwin, & Belton, 2017, in the country, most agricultural lands are owner-operated: 88% in upland and 91% in lowland parcels. The access to lands other than ownership are rare, with lease, shared and mortgaged accounting for only 3.4% of all land parcels operated in the central Myanmar. The data for land rental market in the country is very limited.

Srivinas and Hlaing (2015) found that in many rural areas, there is a growing trend of informal land market with higher land prices which offers the landowners with immediate high amount of cash. This situation entices small and marginal landowners to sell their lands and large landowners to sub-divide and sell a portion of their lands. Based on Agricultural Census 2010, they suggested that the reverse of landowners buying new lands and expanding their existing landholdings may not be occurring. This may be due to the difference between land prices and the net income stream from farming. Binswanger, Deininger, and Feder (1993) stated that if the difference is higher, the farmers will be more reluctant to buy lands and therefore voluntary transactions in sales are less likely to result in increased advantages.

The enactment of the new Farmland Law and the registration of LUCs are expected to strengthen the ownership property rights. LUCs offer transferable rights and are expected to facilitate efficient land market. However, the legal status of tenure has been insecure given the risks of land grabbing or VFM classification system (Baver et al., 2013; McCarthy, 2016; Srivinas & Hlaing, 2015). Despite such tenure insecurity, different forms of informal land transactions have been found out throughout the country.

According to Boutry et al. (2017), sharecropping is the common form of renting which is practiced throughout the country. They are usually made on a seasonal or annual basis. The landowners usually receive the proportion of the harvested produce or cash and receive half of the payment if they wish to obtain the rent ex-ante. Depending on the contractual arrangements, the proportion of the produce may vary from one-third to half. The scarcity of available lands strengthens the landowner’s bargaining power and let them to set the rental conditions and beneficial arrangements for them.

However, Hein et al. (2017) found that the land mortgage arrangement is more popular than sharecropping. In this form, the creditor obtains the land as a pledge for a loan given to the landowner. The creditor gets a temporary land use rights against a loan of a fixed amount and duration is usually several years and the price is usually two-thirds or half of land sale market price. Creditors can be landowners who are seeking to acquire land or landless entrepreneurs who are being unable to buy land at high prices.

There have been limited findings about fixed-rent type of contracting within the country. However, in recent years, mostly in the central part of the country, the landowners are making renting agreement with foreign investors to grow vegetables (Boutry et al., 2017). The agreements are usually fixed-rent, short-term with small-scale farmers. Srivinas and Hlaing (2015) stated that this practice is considered as illegal as the Farmland Law (2012) restrict transferring the use rights to foreigners without permission from the government. Despite this limitation, Antonio (2015) found out that within rental agreements between Chinese investors and local landowners in watermelon cultivations in the central zone, the landowners lease out their lands because of lower investment capacity and the uncertainty of climatic variations.

IMPACTS OF LAND TENURE SYSTEM ON THE PRODUCTIVE USE OF LAND

Impacts of land policies and tenure security

Jepsen, Palm, and Bruun (2019) pointed out that the uncertainty about tenure security in the upland zone because of the lack of statutory use rights is one of the factors that hampers the agricultural intensification. In recent years, there has been serious conflicts between large-scale land acquisition by private sectors and the dispossession of private property or common pool resource by smallholders (Willis, 2013). Mark (2016) found that there have been many discriminatory claiming of the private property or the common pool resources as VFV lands. This may stem from the lack of transparent recognition of existing rights to use the lands for a variety of purposes such as grazing, swiddening, fallowing and shifting cultivations and the poor identification of allocated lands in the VFV and Farmland Laws.

The “30 year Master Plan for the Agriculture Sector” launched in 2000 aimed to convert about 4 million hectares of what is defined as VFV lands into productive lands under private agribusiness (Chao, 2013). Such large-scale agricultural model has been promoted in Myanmar for agricultural development and the government has granted 1,568,547 hectares of VFV land for agriculture purposes (Henley, 2014). This poses a serious question regarding the efficiency of productive use of these granted lands. Thein, Diepart, Moe, and Allaverdian (2018) stated that only 14.89% of the VFV lands granted have actually been cultivated and the rest are left idle. He found out that in some companies, these lands are used as a pretext of agriculture to actually engage in other form of businesses. The rationales for the absence of land rental market for these underutilized VFV lands have not been widely known. According to Deininger and Feder (2001), the large landowners in some countries are reluctant to engage with multiple tenants due to concern for potential challenges to their property rights. The same situation might apply in Myanmar where there are weak tenure security, inefficient legal system, existing conflicts between the local smallholders and the large private businesses for these granted VFV lands. The other reason may be associated with the VFV laws which stated that the granted land use rights under VFV legislations do not contain the right to transfer or subdivide without permission from the government. This poses high unit transaction costs to register and obtain approval from the government for leasing out these lands. Such high transaction cost will attribute to the absence of land rental market for these underutilized granted VFV lands.

Impacts of land market

In Myanmar, most farm-households value their lands as a form of social security and therefore, the existence of rental market is a more reliable indicator of allocative efficiency than sale (Lyne et al., 1997). Renting facilitates productive use of land by transferring land to farmers who can use it more effectively. Deininger and Feder (2001) stated that in situations where the tenants have difficulties in accessing credits to pay up-front and the opportunities of risk-sharing against fluctuations in output, the share contract types are in favor than fixed-rent. This statement is applicable to the popularity of sharecropping in Myanmar where the farmers are facing difficulties in accessing affordable credits for investment, uncertainty of weather and market price for products (Boutry et al., 2 017).

However, Deininger and Feder (2001) also stated that under conditions of weakened enforceability of contracts, any type of contract other than fixed-rent would result in underinvestment of tenants. This is because with other types of contracts, tenants receive only a fraction of their marginal product which would incentivize them to exert less efforts and investment. Therefore, the share contract type of rental market may lead to the allocative efficiency but if the contracts are not strongly enforceable, the lands will not result in intensive use.

In addition, Boutry et al. (2017) found that the sharecropping type of renting in the country is usually among the family, neighbors and friends. Sadoulet, De Janvry, and Fukui (1997) stated that the extent of productive use of land depends on the relationship between the contractual parties. They found that the investments in input usage are higher in sharecropping between the close-kin than with non-kin. This may be associated with high ex-ante transaction costs of searching and negotiating with new contractual partner and the high ex-post transaction costs of enforcing the contracts in case of moral hazard. If the sharecropping is mostly between the close-kin because of high transaction costs, the lands will be less likely to be allocated to the most effective users. The seasonal fixed-renting contracts with foreign investors and mortgage arrangements are not necessarily personalized but sometimes, they are not mutually beneficial. In both of these cases, there are usually power asymmetry between the parties in terms of credit, bargaining power and market information (Boutry et al., 2017). Antonio (2015) found that because of the investment constraints, the landowners in the central Myanmar are subjected to distress renting even when the contracts are not satisfactorily winning in their favor, especially in terms of profitability. Therefore, this poses serious question regarding the effectiveness and productive use of lands whether by the landowners or the tenants under such tenancy arrangements.

Prior to the enactment of the Farmland Law (2012), land cannot be used as collateral to access credit. After issuance of LUCs, the Farmland Law allows banks to accept land as collateral for loans using LUCs. In this context these financial institutions should, theoretically, be able to expand finance for farmers to make investment for productive farming. However, Kirk and Tuan (2009) indicated the evidence in Vietnam where banks are still reluctant to accept land-use certificates as collateral due to the perceived difficulty of seizing land to cover loan defaults. Similarly, Myanmar still have poor legislations and lack of transparent strong legal procedure for the event of foreclosure (Tun et al., 2015) which would make the banks hesitate to offer loan products to farmers. However, evidence in aquaculture research by Boughton et al. (2015) indicated that LUCs are being used as the collateral to access credit but most of them are limited under certain authorized banks. Nevertheless, because of the increasing land grabbing by large agribusinesses and increase in land market value, the farmers who have exclusive ownership with LUCs are expected to have the ability to access credit from upcoming financial institutions.

CONCLUSION

This research intends to analyze how the institutional arrangements for land, in other words, how the tenure system influences the behavior of farmers in productive use of lands. The following section concludes the implications of the land tenure system especially tenure security and land market for the productive use of lands and applications of these concepts in Myanmar.

An efficient land market will impose opportunity costs to farmers who owns underutilized lands. Allocative efficiency therefore improves by shifting lands to the more effective users who can use them more productively. This improves farming efficiency by allowing farmers who are in need of lands for massive farming purposes to reduce unit transaction costs and to benefit from economy of scale. Land market will provide the land with the collateral value to access credit from financial institutions to make investment. In these ways, land market increases the ability and incentive of farmers to use the lands productively.

Myanmar is a Southeast Asia country where agriculture is the main industry, accounting for 22% of the GDP (Agricultureat a Glance 2020, DOP) and employing about 65% of the labor force. Historically, during the military regime (1962–2011), the land rights were under strict control on crop choices and marketing of produce was enforced. However, recent political and economic developments within the country have driven changes to the state land management system. In 2012, the Myanmar government introduced the Farmland Law and the Vacant Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (VFV Law) which significantly altered how agricultural land is managed.

The Farmland Law allows landowners to have exclusive ownership through the issuance of Land Use Certificates (LUCs) which are transferable and marketable. This land titling system has been effective in the central and lowland zones of the country. However, it fails to recognize communal land ownership in the upland zone where the farmers practice shifting cultivations. The law does not recognize shifting cultivations under farmland categories and labels these cultivation areas as waste lands. Therefore, most landowners in the upland zone are lack of statutory ownership.

The VFV law allows farmers and private investors to apply and obtain vacant, fallow and virgin lands. However, it does not contain transparent due procedure in defining the VFV lands to be granted to the applicants and in some cases, misclassifies the common property or private property as vacant. Therefore, most landowners who lack legal ownership, usually those under customary tenure, are under the threat of losing their lands. By 2017, the government has granted nearly 4 million hectares of VFV lands, however, only 14% are under cultivation and the rest are left idle.

Most land market transactions in Myanmar are informal and usually among people with close relations. Sharecropping and mortgage arrangements are the common forms of access to lands apart from ownership. Fixed-rent types are rare throughout the country and the expected reasons may be due to the inability to access credit to pay upfront and due to the prospect of risk-sharing. However, Deininger and Feder (2001) have pointed out that farmers will not have strong incentives to exert efforts and make investment in case of share-rent as they receive only a fraction of their marginal product.