ABSTRACT

In the 1940s, Singapore was a major center of research and experimentation for tilapia breeding and its ponds yielded promise for meeting food requirements. Tilapia was first brought into Singapore by the Japanese community during World War II and, when the tide of World War II turned for the Japanese Empire, its food provisions were running low for the troops and so it reared a unique “imperial fish” for food in occupied Singapore which was originally a tilapia species imported from Java Indonesia but specially bred in Singapore. In the post-war period during the decade of the 1960s, fishing was a major source of employment for Singapore. Fish farming continued to thrive into the 1970s in the Tampines countryside which was dotted with fish pens in fish farms before they were gradually relocated/resettled in phases. In Singapore, inland farming was restricted by land space and, by 1987, only 10 hectares were dedicated for freshwater food fish (Chou, 1994, p. 80). In 1985, the use of high technologies began the process of advanced research into high-density fish farming that would yield results in the 2000s. After 2010, advocates of fish farming argued that Singapore can pare down importation of fish and feed by focusing on high intensity fish farming and the humble tilapia has re-emerged as an important breed. By the end of the 2010s, indoor fish farming utilizing factory industrial spaces aerated by using nano-oxygen technology made high-density fish farming possible. The challenge that Singaporean tilapia breeders had to overcome was educating consumers on the merits of consuming tilapias. Fussy or picky eaters may point out taste or/and smell issues (muddiness, fishiness, staleness or/and foulness) with freshwater fishes like tilapia. After creating consumer awareness of the tilapia’s taste, Singaporean breeders were able to chalk up demand for their products, thereby making voluminous production possible. In Singapore, tilapia fish farms have even become part of rural tourism. Visitors to Singapore can take a farm tour and consume live tilapia catches at the fish farm’s in-house restaurant.

Keywords: tilapia, Singapore, nanobubble, farmed, space

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Tilapia cultivation first appeared in world history in the records of ancient Egypt millennia ago with an Egyptian hieroglyph that connotes this fish that has been around since ancient days (fromSGtoSG, 2020). It was only until mid-20th century that they were systematically bred for high yields as a food fish through the use of modern rational methods of scientific experimentation. International tilapia farming until the 1940s was characterized by experimental pond breeding in Indonesia whose farms reared O. mossambicus tilapias in brackish water ponds and rice paddies as meat proteins for its populations during World War II.

Due to the fog of war and loss of records, there are no precise information about the market size, value, cultivation areas and consumption of tilapia in Singapore. What can be gleaned from that period was one of the more prominent Japanese-owned fish farm joint venture was Taichong Farm (Shimizu, 1997, p. 337) though much of their fishes were caught by fishermen in the open seas. During the Japanese Occupation period, a Fisheries Training School was set up by the Shonan (Singapore's wartime occupation name) authorities where locals were trained in fish breeding (Shimizu, 1997, p. 344). We know that Singapore then was a major center of research and experimentation for tilapia breeding and its ponds yielded more than 1,300 kilograms per hectare which was a positive sign of the tilapias’ promise for meeting food requirements (IFPRI, undated). Tilapia was first brought into Singapore by the Japanese community during World War II and that may be why tilapias are known as ‘Je Pun He’ (Hokkien language for ‘Japanese fish’) in Singapore (Jules of Singapore, 2017). A photo album titled "Memories" curated by First Lieutenant Yuuto during his tour in Java and Singapore reveals more details about tilapia breeding in Singapore as he was placed in charge of this assignment during his time in Singapore (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017).

After the tide of World War II turned for the Japanese Empire, its food provisions were running low for the troops and so it reared a unique “imperial fish” for food in occupied Singapore which was originally a tilapia species imported from Java Indonesia but specially bred in Singapore by a combined military expert team of Japanese and Taiwanese working with local farmers (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017).

However, Singapore’s tropical downpour soon resulted in flooded tilapia farms and the fishes found their way into canals and started to interbreed with other species of tilapia, becoming the wild hybrid tilapia found in Singapore’s drainage system thereafter (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017). They became known as one of the ‘long kau’ fish (pidgin Hokkien local parlance for ‘drain fishes’). After the end of the Pacific War in 1945, two Taiwanese (Guo Qizhang and Wu Zhenhu) who served in Japanese military returned back to the tilapia farms and brought the cultivated fish fry back to Taiwan in 1946 (12 eventually survived) (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017).

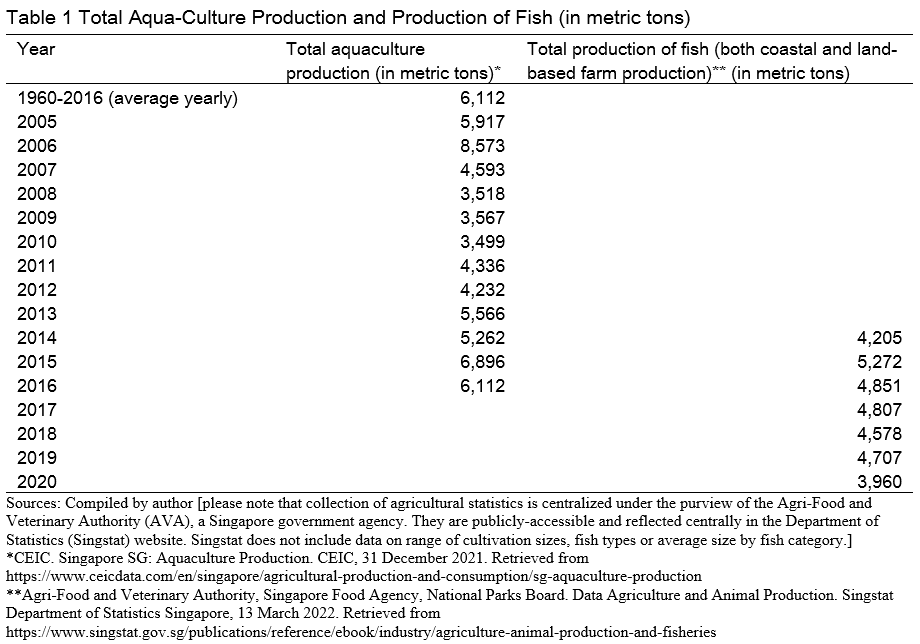

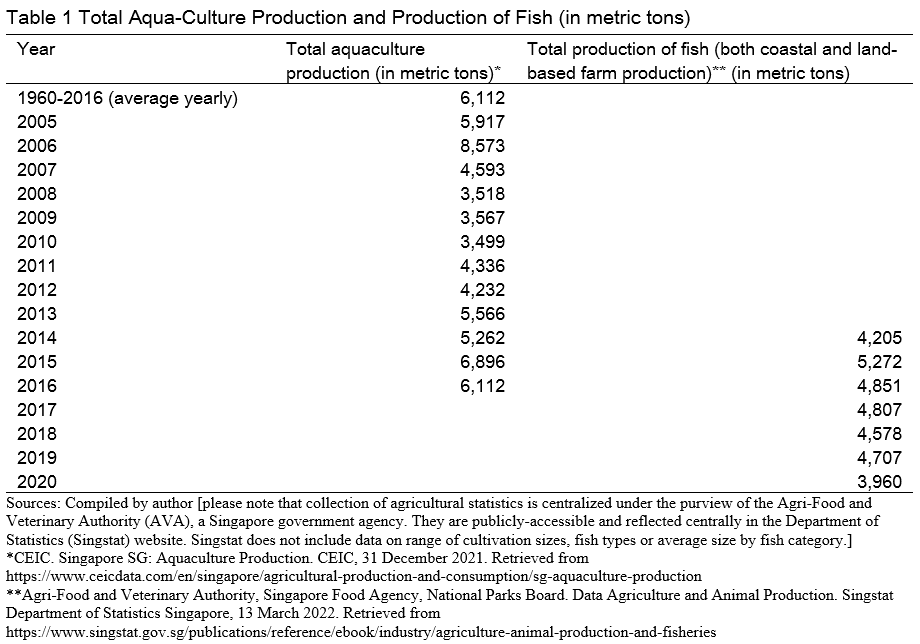

In the post-war period during the decade of the 1960s, fishing was a major source of employment for Singapore, with 20,000 farms in approximately 14,000 ha of land space (AVA, 2015). See Table 1. Besides tilapia, the other fishes bred in Singapore included the marine food fish of Grouper, Seabass, Snapper and Milkfish found in the coastal farms while inland freshwater food fish farms focused on snakehead, tilapia, catfish etc. (Singapore Food Agency, 2021). Fish farming continued to thrive into the 1970s in the Tampines countryside which was dotted with fish pens in fish farms before they were gradually relocated/resettled in phases (National Library Board, 2022). In Singapore, inland farming was restricted by land space and, by 1987, only 3,300 hectares of land were slated for aqua-farming activities and many were brackish water shrimp ponds with smaller than 10 hectares dedicated for freshwater food fish (Chou, 1994, p. 80).

In 1985, the Singapore government began to encourage the use of agro-technology with the deployment of high-tech techniques in sizable intensive farming systems to enhance yields greater than from conventional farming while the authorities turned farming spaces into agro-technology parks (Chou, 1994, p. 80). The use of high technologies began the process of advanced research into high-density fish farming that would yield results in the 2000s.

In 2010, farming came back to vogue again. This was due to a lesson learned just before the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) when a global food crisis happened and increased basic food global prices by 60% while grain prices doubled in 2006-2008, resulting in Thailand and Vietnam limiting exports to shore up domestic supplies (Oi, 2010). This experience reminded Singapore of how much it relied on imported food and fish farms were seen as a way to overcome this challenge (Oi, 2010).

Advocates of fish farming argue that Singapore can pare down importation of fish and feed by focusing on breeding fish species that occupy less space, demand less food supply and are suitable for densely-packed fish farming (Jules of Singapore, 2017). Despite the island-nation’s space constraints, Singapore has a modest but active food fish breeding sector. Amongst the freshwater fish farms, the humble tilapia has re-emerged as an important breed.

By the end of the 2010s, stakeholders of indoor fish farming argued that factory industrial spaces indoor farming has the advantage of sheltering the fish from potential environmental dangers such as plankton bloom and water pollution (fromSGtoSG, 2020). In fact, Singaporean engineer Ng Yiak Say who designs indoor farm environment argued that all organisms, including humans (from the Neanderthals onwards), had instinctively regarded indoor spaces as being safer than outdoors (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

Singaporean engineer Ng Yiak Say conceptualized the Blue Ocean Aquaculture Technology (BOAT) and converted a Tuas industrial area into a fish farm by using nano-oxygen technology to make high-density fish farming possible in densely-populated restrictive spaces (fromSGtoSG, 2020). There are two locally-developed technologies in Singapore that makes high density fish farming possible and BOAT is the only one that uses nano-oxygen technology for indoor fish farming. It is already a world leader in high-density shrimp breeding technology and pioneering in research on high-density rainbow trout breeding (Responsible Seafood Advocate, 2022). Another major company like Singapore Aquaculture Technologies (SAT) specializes more on sea-farm technologies, less relevant to the discussion on tilapia breeding.

Optimal water conditions are necessary for the well-being and the flavor of the fish and so BOAT creates this optimal breeding environment by using nanobubble technology to form an oxygenated space in the tanks with bubbles that are about 100 nanometers and invisible to the human eye as they dissolve instead of bubbling up to the surface, in the process enriching the water and eliminating bacteria (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The 1-3 cm hatchlings are introduced to BOAT at the age of 31 days and reared to adult fish over the next 6-8 months with an indoor environment that can best track the eggs hatching process and genetic development of the tilapias (from nursery to fry to fingerling and then adult phases) (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The BOAT fishes are channelled within an entire production chain process between three autonomous tanks based on their dimensions and maturity before they are harvested, sliced up, de-scaled, vacuum sealed and frozen to lock in the quality and freshness and prevent any foul conditions from emerging (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The challenge that the Singaporean tilapia breeders had to overcome was educating consumers on the merits of consuming tilapias. Fussy or picky eaters may point out taste or/and smell issues (muddiness, fishiness, staleness or/and foulness) with freshwater fishes like Tilapia. Such views are disputed by tilapia fish farmers in Singapore. For example, Alex Siow, the operator of Opal Resources Pte Ltd fish farm at Neo Tiew Lane 1 retorted: Tilapia is not one of the foodie’s choices, reason being, the tilapia that we import, mainly from Malaysia, are mostly grown in freshwater pond. Some foodies claim that there is a trace of mud taste in it. But this issue can be solved with a proper management of the water quality and the use of good feed. The fish is as good as what you feed them. The strangest thing is, Singaporeans often eat grilled fish sold on the streets of Bangkok without knowing it is tilapia. Many restaurants in Singapore also serve the pink tilapia (紅尼羅) …I think children’s taste buds are very sensitive. Perhaps that is why they are usually the picky ones in the family. Kids are able to pick up the slightest fishy taste. I guess live fish which are less fishy is acceptable to them (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

After creating consumer awareness of the tilapia’s taste, Singaporean breeders were able to chalk up demand for their products, thereby making voluminous production possible. BOAT can contribute up to 18 tons of fish (mostly red tilapia and jade perch) to Singapore's fish supply at the current stage (SFA, 2022). General studies on nano-oxygen application indicate that there is lessened operating expenses due to higher stocking densities arising from efficient oxygen production, optimal water quality and lesser energy costs (van Beijnen, Jonah and Gregg Yan, 2021). The case study of Cooke Aquaculture Chile indicated oxygenating one salmon tank with more than 1.5 million fish using three oxygen cones utilizing 134 litres per minute cost US$200 daily to run, compared with a single 10HP nanobubble generator and one oxygen cone using 54 litres of oxygen per minute costing US$100 daily (monthly savings came up to more than US$3,100 and reduce electricity usage by 50%) (van Beijnen, Jonah and Gregg Yan, 2021). Ng’s BOAT output of 18 tons of jade perch (green hued dorsal scale fish) and red tilapia yearly supplies some of Singapore’s most popular fresh seafood chain eateries like the TungLok Group and Paradise Group and supermarkets like RedMart by ordering online (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The soft and sweetish tilapia meat (frozen or live) is getting popular, even replacing salmon meat for some and the flesh can be further marinated with seasoning; in addition, the fillets are well-priced at approximately S$4 (US$2.98) for 4 fillets bigger than the palm sizes and they are good for storage at densely-populated city states because they do not permeate the room with fish smell like the more costly cod or mackerel saba fish (Jules of Singapore, 2017). For the hard-core marine fish eaters, selective breeding made it possible to create the saltwater marine farmed tilapia as Alex Siow (operator of Opal Resources Pte Ltd fish farm at Neo Tiew Lane 1) indicated:

We have worked together with a few kelong [traditional Malay floating fish farms] owners to run a few trials, and the result was fantastic with an astonishing survival rate of more than 90%. We look forward to work closely with the authorities to see how we can scale up the growing of saltwater tilapia (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

All the above-mentioned measures can go some ways in trimming down Singapore’s overreliance on fish imports. Some worry about the overreliance on fish imports in Singapore as a large majority of live or chilled fishes are imported from Indonesia and Malaysia and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) indicated that Singapore acquires 2,500 tons of tilapia annually from Malaysia, China and Indonesia (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

In Singapore, tilapia fish farms have even become part of rural tourism. For visitors to Singapore keen on trying out the farmed tilapias, they can take a farm tour with Opal Resources Pte Ltd fish farm at Neo Tiew Lane 1, request for live tilapia catches, cooked them at the D’Kranji Resort restaurant, including the popular Teochew steamed method that can accentuate their freshness and retain unadulterated taste (and even expose any staleness or foulness) (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

POLICY IMPLICATIONS/CONCLUSION

The Singapore authorities’ initiatives will continue to target high-tech applications for greater yields. It may be possible to seize on the momentum of pandemic-era supply chain disruptions (including food) to foster more self-reliance in food supply, just as it had happened in 1997 (AFC) and 2008 (Lehman Shocks). The policy initiatives are likely to target more at indoor fish farms with converted industrial spaces, given that Singapore’s lower value-added industries are likely to continue to shift to other lower-costs ASEAN economies (e.g. SIJORI growth triangle, Vietnam, etc.). Former industrial spaces can therefore be used for higher value-added activities, given the wealthy, increasing number of lifestyle restaurants and rising socioeconomic middle classes’ penchant for fine food. Moreover, technologies like nanobubble generation can contribute to Singapore’s carbon neutrality goals by saving electricity. In addition, the less fussy procedures of such high-tech farming can also save manpower in Singapore which is an aging population. The authorities can continue to work with farmers and foodies alike (and other stakeholders like restauranteurs) to promote more culinary choices for tilapia consumption. It may be possible to continue to scale up the operations to reach the greater self-reliance goals. All these may also eventually contribute to the macro objectives of saving the Earth’s maritime environment by preventing overfishing, a sustainable development goal that responsible nations like Singapore hold dearly.

REFERENCES

Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA). Celebrating AVA's Excellence Through the Years. AVA, 31 Dec 2015. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-for-thought/article/detail/celebrating-ava's-excellence-through-the-years-(2000-2015)

Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority, Singapore Food Agency, National Parks Board. Data Agriculture and Animal Production. Singstat Department of Statistics Singapore, 13 March 2022. Retrieved from https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/reference/ebook/industry/agricu...

CEIC. Singapore SG: Aquaculture Production. CEIC, 31 December 2021. Retrieved from https://www.ceicdata.com/en/singapore/agricultural-production-and-consum...

Chou, Renee. Aquaculture Development in Singapore. Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC), 1994. Retrieved from https://repository.seafdec.org.ph/bitstream/handle/10862/104/adsea91p079...

fromSGtoSG. Blue Ocean Aquaculture Technology. fromSGtoSG, 21 August 2020. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/fromSGtoSG/farms/farm/Detail/blue-ocean-aquacultu...

Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ). The Tilapia in Singapore. Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ), 31 December 2017. Retrieved from https://www.criticalzoologists.org/thebizarrehonour/tilapia.html

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Global History of Tilapia. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), undated. Retrieved from https://ebrary.ifpri.org

Jules of Singapore. Why Would Singaporeans Buy Fish From a Farmer Instead of A Fisherman? Medium.com, 28 March 2017. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@julesofSG/why-would-singaporeans-buy-fish-from-a-far...

National Library Board (NLB). Fish farming in rural Tampines, 1970s. National Library Board (LNB) Government of Singapore, 31 December 2022. Retrieved from https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/image.aspx?id=45339268-f9b1-...

Oi, Mariko. Farming fish in Singapore self-sufficiency drive. BBC News, 3 May 2010. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/10095333

Responsible Seafood Advocate. Blue Aqua to develop Singapore’s first high-tech trout farm. Global Seafood Alliance, 11 January 2022. Retrieved from https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/blue-aqua-to-develop-singapores-f...

Shimizu, Hiroshi. The Japanese Fisheries Based in Singapore, 1892-1945. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, September 1997. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20071952.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ad1045...

Singapore Food Agency (SFA). Coastal Fish Farming in Singapore. Singapore Food Agency (SFA), 9 November 2021. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-farming/food-farms/coastal-fish-farming-in-s...

Singapore Food Agency (SFA). Blue Ocean Aqua Technology. Singapore Food Agency (SFA) A Singapore Government Agency Website, 17 February 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/fromSGtoSG/farms/farm/Detail/blue-ocean-aquacultu...

van Beijnen, Jonah and Gregg Yan. A breath of fresh air: how nanobubbles can make aquaculture more sustainable. The Fish Site, 13 October 2021. Retrieved from https://thefishsite.com/articles/a-breath-of-fresh-air-how-nanobubbles-c...

Development of Tilapia Farming in Singapore

ABSTRACT

In the 1940s, Singapore was a major center of research and experimentation for tilapia breeding and its ponds yielded promise for meeting food requirements. Tilapia was first brought into Singapore by the Japanese community during World War II and, when the tide of World War II turned for the Japanese Empire, its food provisions were running low for the troops and so it reared a unique “imperial fish” for food in occupied Singapore which was originally a tilapia species imported from Java Indonesia but specially bred in Singapore. In the post-war period during the decade of the 1960s, fishing was a major source of employment for Singapore. Fish farming continued to thrive into the 1970s in the Tampines countryside which was dotted with fish pens in fish farms before they were gradually relocated/resettled in phases. In Singapore, inland farming was restricted by land space and, by 1987, only 10 hectares were dedicated for freshwater food fish (Chou, 1994, p. 80). In 1985, the use of high technologies began the process of advanced research into high-density fish farming that would yield results in the 2000s. After 2010, advocates of fish farming argued that Singapore can pare down importation of fish and feed by focusing on high intensity fish farming and the humble tilapia has re-emerged as an important breed. By the end of the 2010s, indoor fish farming utilizing factory industrial spaces aerated by using nano-oxygen technology made high-density fish farming possible. The challenge that Singaporean tilapia breeders had to overcome was educating consumers on the merits of consuming tilapias. Fussy or picky eaters may point out taste or/and smell issues (muddiness, fishiness, staleness or/and foulness) with freshwater fishes like tilapia. After creating consumer awareness of the tilapia’s taste, Singaporean breeders were able to chalk up demand for their products, thereby making voluminous production possible. In Singapore, tilapia fish farms have even become part of rural tourism. Visitors to Singapore can take a farm tour and consume live tilapia catches at the fish farm’s in-house restaurant.

Keywords: tilapia, Singapore, nanobubble, farmed, space

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Tilapia cultivation first appeared in world history in the records of ancient Egypt millennia ago with an Egyptian hieroglyph that connotes this fish that has been around since ancient days (fromSGtoSG, 2020). It was only until mid-20th century that they were systematically bred for high yields as a food fish through the use of modern rational methods of scientific experimentation. International tilapia farming until the 1940s was characterized by experimental pond breeding in Indonesia whose farms reared O. mossambicus tilapias in brackish water ponds and rice paddies as meat proteins for its populations during World War II.

Due to the fog of war and loss of records, there are no precise information about the market size, value, cultivation areas and consumption of tilapia in Singapore. What can be gleaned from that period was one of the more prominent Japanese-owned fish farm joint venture was Taichong Farm (Shimizu, 1997, p. 337) though much of their fishes were caught by fishermen in the open seas. During the Japanese Occupation period, a Fisheries Training School was set up by the Shonan (Singapore's wartime occupation name) authorities where locals were trained in fish breeding (Shimizu, 1997, p. 344). We know that Singapore then was a major center of research and experimentation for tilapia breeding and its ponds yielded more than 1,300 kilograms per hectare which was a positive sign of the tilapias’ promise for meeting food requirements (IFPRI, undated). Tilapia was first brought into Singapore by the Japanese community during World War II and that may be why tilapias are known as ‘Je Pun He’ (Hokkien language for ‘Japanese fish’) in Singapore (Jules of Singapore, 2017). A photo album titled "Memories" curated by First Lieutenant Yuuto during his tour in Java and Singapore reveals more details about tilapia breeding in Singapore as he was placed in charge of this assignment during his time in Singapore (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017).

After the tide of World War II turned for the Japanese Empire, its food provisions were running low for the troops and so it reared a unique “imperial fish” for food in occupied Singapore which was originally a tilapia species imported from Java Indonesia but specially bred in Singapore by a combined military expert team of Japanese and Taiwanese working with local farmers (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017).

However, Singapore’s tropical downpour soon resulted in flooded tilapia farms and the fishes found their way into canals and started to interbreed with other species of tilapia, becoming the wild hybrid tilapia found in Singapore’s drainage system thereafter (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017). They became known as one of the ‘long kau’ fish (pidgin Hokkien local parlance for ‘drain fishes’). After the end of the Pacific War in 1945, two Taiwanese (Guo Qizhang and Wu Zhenhu) who served in Japanese military returned back to the tilapia farms and brought the cultivated fish fry back to Taiwan in 1946 (12 eventually survived) (Institute of Critical Zoologists, 2017).

In the post-war period during the decade of the 1960s, fishing was a major source of employment for Singapore, with 20,000 farms in approximately 14,000 ha of land space (AVA, 2015). See Table 1. Besides tilapia, the other fishes bred in Singapore included the marine food fish of Grouper, Seabass, Snapper and Milkfish found in the coastal farms while inland freshwater food fish farms focused on snakehead, tilapia, catfish etc. (Singapore Food Agency, 2021). Fish farming continued to thrive into the 1970s in the Tampines countryside which was dotted with fish pens in fish farms before they were gradually relocated/resettled in phases (National Library Board, 2022). In Singapore, inland farming was restricted by land space and, by 1987, only 3,300 hectares of land were slated for aqua-farming activities and many were brackish water shrimp ponds with smaller than 10 hectares dedicated for freshwater food fish (Chou, 1994, p. 80).

In 1985, the Singapore government began to encourage the use of agro-technology with the deployment of high-tech techniques in sizable intensive farming systems to enhance yields greater than from conventional farming while the authorities turned farming spaces into agro-technology parks (Chou, 1994, p. 80). The use of high technologies began the process of advanced research into high-density fish farming that would yield results in the 2000s.

In 2010, farming came back to vogue again. This was due to a lesson learned just before the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) when a global food crisis happened and increased basic food global prices by 60% while grain prices doubled in 2006-2008, resulting in Thailand and Vietnam limiting exports to shore up domestic supplies (Oi, 2010). This experience reminded Singapore of how much it relied on imported food and fish farms were seen as a way to overcome this challenge (Oi, 2010).

Advocates of fish farming argue that Singapore can pare down importation of fish and feed by focusing on breeding fish species that occupy less space, demand less food supply and are suitable for densely-packed fish farming (Jules of Singapore, 2017). Despite the island-nation’s space constraints, Singapore has a modest but active food fish breeding sector. Amongst the freshwater fish farms, the humble tilapia has re-emerged as an important breed.

By the end of the 2010s, stakeholders of indoor fish farming argued that factory industrial spaces indoor farming has the advantage of sheltering the fish from potential environmental dangers such as plankton bloom and water pollution (fromSGtoSG, 2020). In fact, Singaporean engineer Ng Yiak Say who designs indoor farm environment argued that all organisms, including humans (from the Neanderthals onwards), had instinctively regarded indoor spaces as being safer than outdoors (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

Singaporean engineer Ng Yiak Say conceptualized the Blue Ocean Aquaculture Technology (BOAT) and converted a Tuas industrial area into a fish farm by using nano-oxygen technology to make high-density fish farming possible in densely-populated restrictive spaces (fromSGtoSG, 2020). There are two locally-developed technologies in Singapore that makes high density fish farming possible and BOAT is the only one that uses nano-oxygen technology for indoor fish farming. It is already a world leader in high-density shrimp breeding technology and pioneering in research on high-density rainbow trout breeding (Responsible Seafood Advocate, 2022). Another major company like Singapore Aquaculture Technologies (SAT) specializes more on sea-farm technologies, less relevant to the discussion on tilapia breeding.

Optimal water conditions are necessary for the well-being and the flavor of the fish and so BOAT creates this optimal breeding environment by using nanobubble technology to form an oxygenated space in the tanks with bubbles that are about 100 nanometers and invisible to the human eye as they dissolve instead of bubbling up to the surface, in the process enriching the water and eliminating bacteria (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The 1-3 cm hatchlings are introduced to BOAT at the age of 31 days and reared to adult fish over the next 6-8 months with an indoor environment that can best track the eggs hatching process and genetic development of the tilapias (from nursery to fry to fingerling and then adult phases) (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The BOAT fishes are channelled within an entire production chain process between three autonomous tanks based on their dimensions and maturity before they are harvested, sliced up, de-scaled, vacuum sealed and frozen to lock in the quality and freshness and prevent any foul conditions from emerging (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The challenge that the Singaporean tilapia breeders had to overcome was educating consumers on the merits of consuming tilapias. Fussy or picky eaters may point out taste or/and smell issues (muddiness, fishiness, staleness or/and foulness) with freshwater fishes like Tilapia. Such views are disputed by tilapia fish farmers in Singapore. For example, Alex Siow, the operator of Opal Resources Pte Ltd fish farm at Neo Tiew Lane 1 retorted: Tilapia is not one of the foodie’s choices, reason being, the tilapia that we import, mainly from Malaysia, are mostly grown in freshwater pond. Some foodies claim that there is a trace of mud taste in it. But this issue can be solved with a proper management of the water quality and the use of good feed. The fish is as good as what you feed them. The strangest thing is, Singaporeans often eat grilled fish sold on the streets of Bangkok without knowing it is tilapia. Many restaurants in Singapore also serve the pink tilapia (紅尼羅) …I think children’s taste buds are very sensitive. Perhaps that is why they are usually the picky ones in the family. Kids are able to pick up the slightest fishy taste. I guess live fish which are less fishy is acceptable to them (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

After creating consumer awareness of the tilapia’s taste, Singaporean breeders were able to chalk up demand for their products, thereby making voluminous production possible. BOAT can contribute up to 18 tons of fish (mostly red tilapia and jade perch) to Singapore's fish supply at the current stage (SFA, 2022). General studies on nano-oxygen application indicate that there is lessened operating expenses due to higher stocking densities arising from efficient oxygen production, optimal water quality and lesser energy costs (van Beijnen, Jonah and Gregg Yan, 2021). The case study of Cooke Aquaculture Chile indicated oxygenating one salmon tank with more than 1.5 million fish using three oxygen cones utilizing 134 litres per minute cost US$200 daily to run, compared with a single 10HP nanobubble generator and one oxygen cone using 54 litres of oxygen per minute costing US$100 daily (monthly savings came up to more than US$3,100 and reduce electricity usage by 50%) (van Beijnen, Jonah and Gregg Yan, 2021). Ng’s BOAT output of 18 tons of jade perch (green hued dorsal scale fish) and red tilapia yearly supplies some of Singapore’s most popular fresh seafood chain eateries like the TungLok Group and Paradise Group and supermarkets like RedMart by ordering online (fromSGtoSG, 2020).

The soft and sweetish tilapia meat (frozen or live) is getting popular, even replacing salmon meat for some and the flesh can be further marinated with seasoning; in addition, the fillets are well-priced at approximately S$4 (US$2.98) for 4 fillets bigger than the palm sizes and they are good for storage at densely-populated city states because they do not permeate the room with fish smell like the more costly cod or mackerel saba fish (Jules of Singapore, 2017). For the hard-core marine fish eaters, selective breeding made it possible to create the saltwater marine farmed tilapia as Alex Siow (operator of Opal Resources Pte Ltd fish farm at Neo Tiew Lane 1) indicated:

We have worked together with a few kelong [traditional Malay floating fish farms] owners to run a few trials, and the result was fantastic with an astonishing survival rate of more than 90%. We look forward to work closely with the authorities to see how we can scale up the growing of saltwater tilapia (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

All the above-mentioned measures can go some ways in trimming down Singapore’s overreliance on fish imports. Some worry about the overreliance on fish imports in Singapore as a large majority of live or chilled fishes are imported from Indonesia and Malaysia and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) indicated that Singapore acquires 2,500 tons of tilapia annually from Malaysia, China and Indonesia (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

In Singapore, tilapia fish farms have even become part of rural tourism. For visitors to Singapore keen on trying out the farmed tilapias, they can take a farm tour with Opal Resources Pte Ltd fish farm at Neo Tiew Lane 1, request for live tilapia catches, cooked them at the D’Kranji Resort restaurant, including the popular Teochew steamed method that can accentuate their freshness and retain unadulterated taste (and even expose any staleness or foulness) (Jules of Singapore, 2017).

POLICY IMPLICATIONS/CONCLUSION

The Singapore authorities’ initiatives will continue to target high-tech applications for greater yields. It may be possible to seize on the momentum of pandemic-era supply chain disruptions (including food) to foster more self-reliance in food supply, just as it had happened in 1997 (AFC) and 2008 (Lehman Shocks). The policy initiatives are likely to target more at indoor fish farms with converted industrial spaces, given that Singapore’s lower value-added industries are likely to continue to shift to other lower-costs ASEAN economies (e.g. SIJORI growth triangle, Vietnam, etc.). Former industrial spaces can therefore be used for higher value-added activities, given the wealthy, increasing number of lifestyle restaurants and rising socioeconomic middle classes’ penchant for fine food. Moreover, technologies like nanobubble generation can contribute to Singapore’s carbon neutrality goals by saving electricity. In addition, the less fussy procedures of such high-tech farming can also save manpower in Singapore which is an aging population. The authorities can continue to work with farmers and foodies alike (and other stakeholders like restauranteurs) to promote more culinary choices for tilapia consumption. It may be possible to continue to scale up the operations to reach the greater self-reliance goals. All these may also eventually contribute to the macro objectives of saving the Earth’s maritime environment by preventing overfishing, a sustainable development goal that responsible nations like Singapore hold dearly.

REFERENCES

Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA). Celebrating AVA's Excellence Through the Years. AVA, 31 Dec 2015. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-for-thought/article/detail/celebrating-ava's-excellence-through-the-years-(2000-2015)

Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority, Singapore Food Agency, National Parks Board. Data Agriculture and Animal Production. Singstat Department of Statistics Singapore, 13 March 2022. Retrieved from https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/reference/ebook/industry/agricu...

CEIC. Singapore SG: Aquaculture Production. CEIC, 31 December 2021. Retrieved from https://www.ceicdata.com/en/singapore/agricultural-production-and-consum...

Chou, Renee. Aquaculture Development in Singapore. Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC), 1994. Retrieved from https://repository.seafdec.org.ph/bitstream/handle/10862/104/adsea91p079...

fromSGtoSG. Blue Ocean Aquaculture Technology. fromSGtoSG, 21 August 2020. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/fromSGtoSG/farms/farm/Detail/blue-ocean-aquacultu...

Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ). The Tilapia in Singapore. Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ), 31 December 2017. Retrieved from https://www.criticalzoologists.org/thebizarrehonour/tilapia.html

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Global History of Tilapia. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), undated. Retrieved from https://ebrary.ifpri.org

Jules of Singapore. Why Would Singaporeans Buy Fish From a Farmer Instead of A Fisherman? Medium.com, 28 March 2017. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@julesofSG/why-would-singaporeans-buy-fish-from-a-far...

National Library Board (NLB). Fish farming in rural Tampines, 1970s. National Library Board (LNB) Government of Singapore, 31 December 2022. Retrieved from https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/printheritage/image.aspx?id=45339268-f9b1-...

Oi, Mariko. Farming fish in Singapore self-sufficiency drive. BBC News, 3 May 2010. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/10095333

Responsible Seafood Advocate. Blue Aqua to develop Singapore’s first high-tech trout farm. Global Seafood Alliance, 11 January 2022. Retrieved from https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/blue-aqua-to-develop-singapores-f...

Shimizu, Hiroshi. The Japanese Fisheries Based in Singapore, 1892-1945. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, September 1997. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20071952.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ad1045...

Singapore Food Agency (SFA). Coastal Fish Farming in Singapore. Singapore Food Agency (SFA), 9 November 2021. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-farming/food-farms/coastal-fish-farming-in-s...

Singapore Food Agency (SFA). Blue Ocean Aqua Technology. Singapore Food Agency (SFA) A Singapore Government Agency Website, 17 February 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sfa.gov.sg/fromSGtoSG/farms/farm/Detail/blue-ocean-aquacultu...

van Beijnen, Jonah and Gregg Yan. A breath of fresh air: how nanobubbles can make aquaculture more sustainable. The Fish Site, 13 October 2021. Retrieved from https://thefishsite.com/articles/a-breath-of-fresh-air-how-nanobubbles-c...