ABSTRACT

Japan has a unique place in the history of futures trading, as the Dojima Rice Market in Osaka, established in 1697 and authorized in 1730, is said to be the first case in the world that a futures market for any commodity was operated under the official government permission. This indicates the use of rice as quasi-money in the Tokugawa Shogunate period. Even after the Meiji Restoration (1868), the Dojima Rice Market had been an active social infrastructure. However, the government closed the Dojima Rice Market in 1939 when the government employed strict controls on rice marketing under a serious food shortage resulting from Japan’s expansion of military action. The government’s control on rice marketing continued into the American Army’s occupation immediately after the Second World War due to the continuing severe food shortage. While Japan regained sovereignty and became food abundant in the 1950s, the government continued its control on rice marketing by redirecting its intentions toward supporting farmers’ income. In 2003, as a part of the government’s deregulation policy, the government abolished most of its control on rice marketing. This created an atmosphere for re-opening the futures market for rice. The biggest obstacle to such a market is a prevailing negative public perception of futures markets. For years, dishonest traders made uninvited solicitations, using commodity futures market to cheat the public. This became a serious social problem. While the futures market for rice opened in 2011 under a temporary license from the government, it was eventually closed in 2021 although there were no uninvited solicitations at the futures market for rice between 2011 and 2021. If the Japanese general public had proper understanding on merits of futures markets, the rice futures market would have been kept active even now.

Keywords: Agricultural Cooperative Law, Commodity Futures Law, Food Control Law, Liberal Democratic Party, Staple Food Law

INTRODUCTION

A futures market for any commodity possesses merits on the free market economy (or a capitalist society). Thus, a futures market provides an opportunity for stabilizing income for those who want to avoid the risk of leaps and plunges in commodity prices. In addition, it provides an opportunity of high-risk but high-return in investments for those who can afford to take the risk of price fluctuations. Moreover, by observing the pricing results at a futures market, businesspersons and researchers share information on demand-supply condition of the commodity.

In spite of these merits, on August 7, 2021, the Japanese government decided to close the rice futures market. Why did the Japanese government make such a decision? By reviewing the long history of Japan’s rice market policy, this paper aims to explain the reason behind the closure of the country’s rice futures market.

JAPAN’S RICE POLICY FROM THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE PERIOD TO THE MIDDLE OF THE 1930s

Together with corn and wheat, rice is one of the three major crops in the world. For people in monsoon Asia, rice is an especially important crop. Japan is not an exception. Since ancient times, rice has been the staple food of the Japanese[1].

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s foremost priority was promotion of rice production. Farmers were not allowed to plant any crops other than rice unless they received special permission.

While the Tokugawa Shogunate employed the gold and silver bimetallism, rice also functioned as quasi-money. For example, farmers were obliged to pay tax with rice. Salaries of samurai were paid with rice. Merchandizers settle accounts by exchanging certificates of rice deposits in warehouses. The wealth (and economic ranking) of a han (feudal domain in the Tokugawa Shogunate period) was measured by how much rice a han was able to produce.

In the Tokugawa Shogunate period, Dojima, a hinterland of a major port in Osaka, became a prosperous and busy business district. In 1697, merchandizers in Dojima set up a permanent market for rice futures trading on their own. This was called the Dojima Rice Market. In 1730, recognizing the social merits of futures trading at the Dojima Rice Market, the Tokugawa Shogunate authorized the Dojima Rice Market by issuing a formal certificate, recognizing it as a social infrastructure. This is believed to be the first case in the world that a futures market obtained approval from the national authorities (or the ruler of the country)[2].

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 marked the turning point of Japanese society. The feudalistic authorities of the Tokugawa Shogunate collapsed and a new central government, called the Meiji government, started ruling over Japan. Meiji is the name of an imperial era from 1868 to 1912. A major objective of the Meiji government was the promotion of capitalistic economic development. To do so, the Meiji government abolished many of old customs. For example, the Meiji government required farmers to pay tax in cash, instead of paying with rice).

The Meiji government recognized that futures trading for rice was favorable for Japan’s capitalistic economic development. Thus, the Meiji government also made the Dojima Rice Market an official market. As the Meiji Emperor passed away in 1912, the imperial era name changed from Meiji to Taisho. When the Taisho Emperor passed away in 1926, the imperial era name changed from Taisho to Showa. Until around the middle of the 1930s, and through two name changes of the imperial period as mentioned above, the Japanese government’s top priority, i.e., capitalistic economic development, remained unchanged. Futures trading continued actively at the Dojima Rice Market, and the daily pricing results at the Dojima Rice Market had been used as a key indicator of the Japanese economy among businesspersons, researchers, and politicians.

RICE POLICY IN THE WARTIME PERIOD

Japan’s full-scale militarization, which started in the middle of 1930s brought a drastic change in the rice market[3]. According to the expansion of the war fronts, the Japanese government conscripted more and more young farmers into the army. In addition, the Japanese government prioritized the distribution of raw materials to military uses, instead of civilian uses such as equipment and materials for farming. As a result, rice became in short supply. Rice prices on the futures and real markets spiked to an intolerable level for the general public. As a part of the Japanese government’s reaction to the rice shortage, the government ordered the closure of the Dojima Rice Market in 1939[4].

In addition, as a part of the general mobilization policy, the government established a nationwide farmers’ organization, called Nogyokai, in 1943. Each municipality had to have a local office of Nogyokai, and the mayor of the municipality appointed a director. Every farmer was obliged to be part of the local office of Nogyokai in his or her municipality.

Using the Nogyokai system, the Japanese government established the government-laid rice marketing system, called Food Control System. All the rice marketing was controlled by the Food Distribution Corporation, a government-affiliated corporation. Every farmer sold all the rice in excess of his or her family’s consumption to the Food Distribution Corporation through Nogyokai. Then, all the rice was distributed to consumers through the channels designated by the Food Distribution Corporation. The Food Control Law provided the legal basis for the Food Control System.

RICE POLICY UNDER THE OCCUPATION AUTHORITIES’ RULE

In August 1945, Japan announced an unconditional surrender to the Allied Powers led by the United States. For four years and six months since then, the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) administered Japan. The top agenda of the GHQ’s administration was to reform Japan into a democratic country that is aligned with the Western (or anti-Communist) bloc.

Treatment of Nogyokai was one of the biggest problems for the GHQ. Two contrasting views on Nogyokai prevailed: One view was that Nogyokai should be maintained because Nogyokai played a key role of procuring rice from farmers in the Food Control System, which was essential in keeping Japanese people fed in the face of limited rice production capacity. Another view was that, since Nogyokai was a part of the previous militaristic regime, Nogyokai should be dissolved in order to democratize Japanese society.

The GHQ’s decision was the establishment a new farmers’ organization, called Nokyo, taking the place of Nogyokai in the Food Control System. The legal basis for Nokyo was (and still is) the Agricultural Cooperative Law promulgated in November 1947. Nogyokai was dissolved in August 1948.

In 1949, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) reorganized the entire departmental system[5]. As part of the revision, the Food Agency was established as an extra-ministerial bureau responsible for the Food Control System. This was the same responsibility that the Food Distribution Corporation had borne before the GHQ reined over Japan).

In 1951, Japan regained its sovereignty and the GHQ was dissolved. In the 1950s, the manufacturing industry grew faster than the agricultural sector then, the income gap between farmers in rural areas and salaried workers in urban areas increased to a politically intolerable level.

Japan recovered from the war damages, and food supply became sufficient in the 1950s. The timing was thought to be right for abolishing the Food Control System. However, the government kept the Food Control System by changing its purpose—to support farmers’ income level. The following sections show how farmers’ income was supported through the Food Control System.

THE NOKYO SYSTEM

Before talking more about the Food Control System, it should be useful to have a quick review of the Nokyo system.

Nokyo had (and still has) two faces: as a democratic organization whereby farmers work together for mutual economic benefits; and, as de facto sub-governmental body, which collaborates with the government in implementing the government’s agricultural policy.

The Nokyo system has a three-tier structure. Unit cooperatives in villages, towns, and cities constitute the first level. The unit cooperatives are in direct contact with farmers; each unit cooperative has its own jurisdiction and does not overlap with any other jurisdiction. Although there is no legal requirement, most farmers join Nokyo as regular members of the unit cooperatives where they live.

The second tier consists of two associations in each prefecture. One is the prefectural federation of agricultural cooperatives, which is engaged in economic activities such as joint shipping of agricultural commodities. The other is the prefectural union of agricultural cooperatives, which are engaged in political activities such as campaign for import tariffs on foreign agricultural products. All the unit cooperatives in each prefecture belong to both the prefectural union of agricultural cooperatives and prefectural federation of agricultural cooperatives (Japan consists of 47 prefectures). At the third tier, Nokyo has two associations (as described later, one of them was dissolved after the revision of the Agricultural Cooperative Law in 2015): the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, which integrates the 47 prefectural unions of agricultural cooperatives, and the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, which integrates the 47 prefectural federations of agricultural cooperatives. As such, Nokyo can be seen as a mammoth system for farmers’ economic and political activities. However, as mentioned later, the revision of the Agricultural Cooperative Law in 2015 deprived Nokyo of political power.

RICE POLICY IN THE 1960s

The Food Control System had been effective until 2003. During this period, it had occasionally received revisions. Major revisions took place twice: the first in 1970 and the second in 1994.

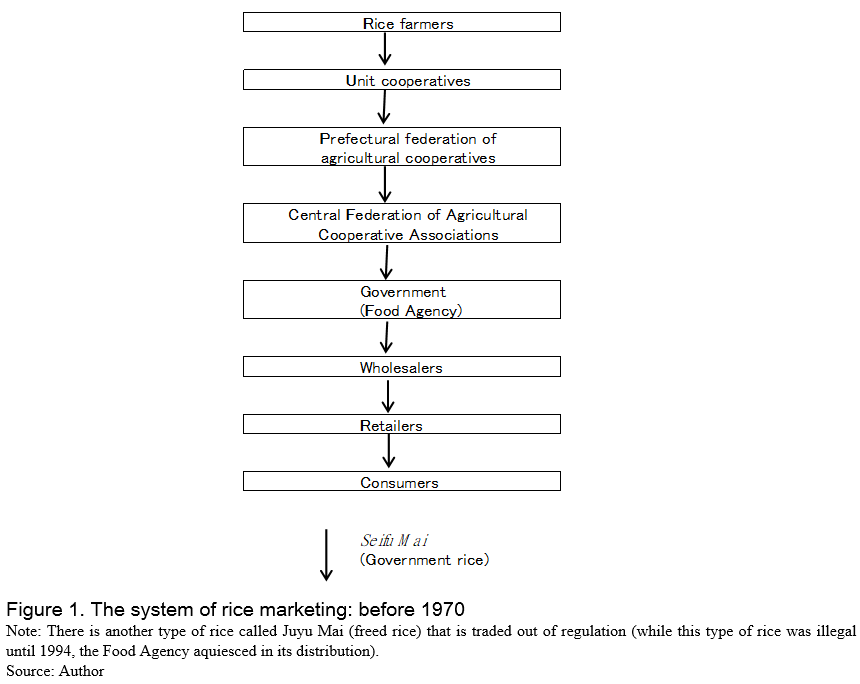

Figure 1 shows the structure of Food Control System until 1970. Farmers were obliged to supply rice to unit cooperatives in their villages. Then, through prefectural federations of agricultural cooperatives and the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, the Food Agency procured rice. Distribution channels from the Food Agency to consumers were also strictly regulated. The wholesalers and retailers of rice need licenses from the prefectural governors. The timing and volume of transaction between wholesalers and retailers were also controlled by the Food Agency.

The Food Agency’s selling and procurement prices were determined before the harvest season. In addition, the marketing margins for unit agricultural cooperatives, prefectural federation of agricultural cooperatives, the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, rice wholesalers, and rice retailers were also fixed by the Food Agency. In sum, the Food Agency controlled all rice transactions, from farmers to consumers.

In the early 1950s, Japan’s miraculous high-speed economic growth started. The annual economic growth rate in this period was nearly 10%. In particular, the manufacturing sector prospered by borrowing advanced technologies from European and North American countries. While agricultural productivity increased, the growth rate of the agriculture sector was much lower than that of the manufacturing sector. In addition, demands for manufactured commodities grew faster than that for agricultural commodities. As a result, the income gap – and living conditions – between farm households and their urban counterparts widened and became one of the biggest political concerns in the late 1950s.

In 1960, the government employed a unique rice price-determination formula called Production Cost Compensation Program. In this formula, the government procurement price was determined in a way that the cost of rice production is covered, including unpaid family labor which was estimated as the wage rate in the manufacturing sector. Based on this formula, the government raised its procurement price for rice corresponding to the rapid wage increases in the manufacturing sector. Accordingly, the ratio between domestic rice price and international price increased sharply. Since the government prohibited rice imports, foreign rice did not flow into Japan[6].

The government’s high procurement price stimulated rice production. Although the government set rice sales price lower than its procurement price, rice stocks accumulated. This is because the eating habits of Japanese consumers have become more western; consequently demand for rice decreased at an unexpectedly high speed. As a result, the burden of national budgets for rice price support increased in two ways. First, since the government sold rice with negative margin, the government allocated special budgets to fill the gap between sales price and procurement price. Second, the government bore the cost of rice storage (including disposal costs of old rice).

RICE POLICY IN THE 1970s

The national budgetary burden for rice price support increased to a politically intolerable level at the end of the 1960s. In addition, the average income of farmers exceeded that of salaried workers in urban areas around 1970 as a result of the government’s rice price support policy and increased income from off-farm employment.

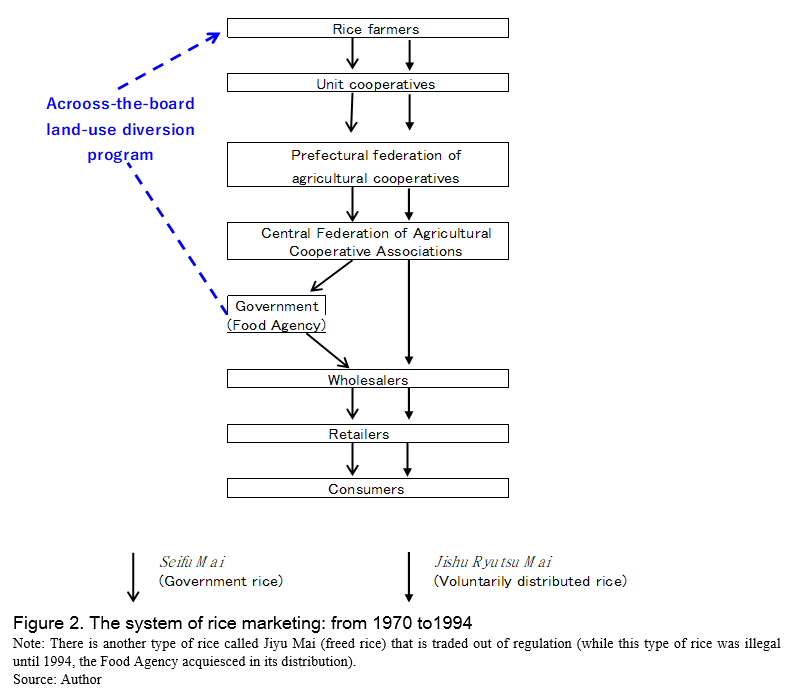

As such, around 1970 seemed an appropriate moment for the government to suspend rice price support and liberalize rice marketing by abandoning the Food Control System. However, that was not what the government chose to do. Instead, the government launched two measures to reduce the fiscal expenditure on rice marketing. First, the government allowed rice wholesalers to purchase rice directly from the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, bypassing the Food Agency. This type of rice was called voluntarily distributed rice (Jishu Ryutu Mai in Japanese). This new system encouraged production of high-quality rice (good taste rice) that could not be priced adequately in the procurement of the Food Agency.

The rice purchased by the Food Agency was called government rice (Seifu Mai in Japanese). Besides government rice and voluntarily distributed rice, some rice was illegally distributed out of the Food Control Law. Such rice was called freed rice (Jiyu Mai in Japanese).

It should be noted that consumers’ requests on the quality of rice became more and more diversified in the 1960s as consumers became more discriminating in their tastes for rice. However, the Food Control System was too strict, even after the introduction of voluntarily distributed rice. Thus, the government often connived with those engaged in buying and/or selling rice out of the framework of the Food Control System. Figure 2 illustrates the system of the Japanese rice market after 1970.

Another measure for curbing the national budgetary burden was the across-the-board land use diversion program. This program can be seen as a government-led rice production cartel. The government at first set the target acreage that should be diverted from rice planting so as to prevent excess supply of rice. With the collaboration of Nokyo, the target acreage was allocated into all the villages. All farmers in the villages collaborated to achieve the allocated acreages.

While the government provided financial support to rice farmers according to the acreage diverted from rice planting, it did not fully compensate the reduction of rice income at the microeconomic level. But, in the aggregate, the cartel effect of the across-the-board land use diversion program benefitted rice farmers as high rice price was maintained[7]. As a result, the target acreage is achieved at nearly 100 % every year.

While the across-the-board land use diversion program was originally introduced in 1970 as an emergency (or temporary) countermeasure against the excess accumulation of old rice stock, it had continued for more than 30 years since then.

LIBERALIZATION OF RICE MARKETING

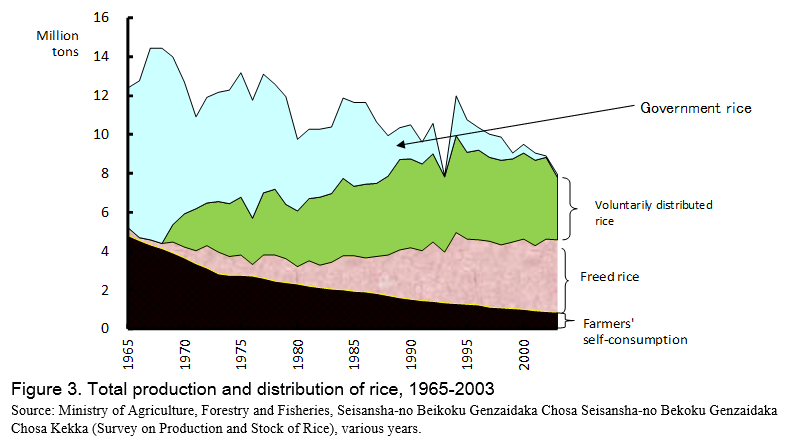

By the early 1990s, the percentage of government rice decreased to less than 5% in the rice market (Figure 3). In addition, although the legal basis for freed rice was not secure, the percentage of freed rice as well as that of voluntarily distributed rice kept increasing. Responding to this situation, the government submitted a new law, called Staple Food Law, to the Diet in 1994. The Staple Food Law came into force in 1995 and the Food Control Law was abolished then.

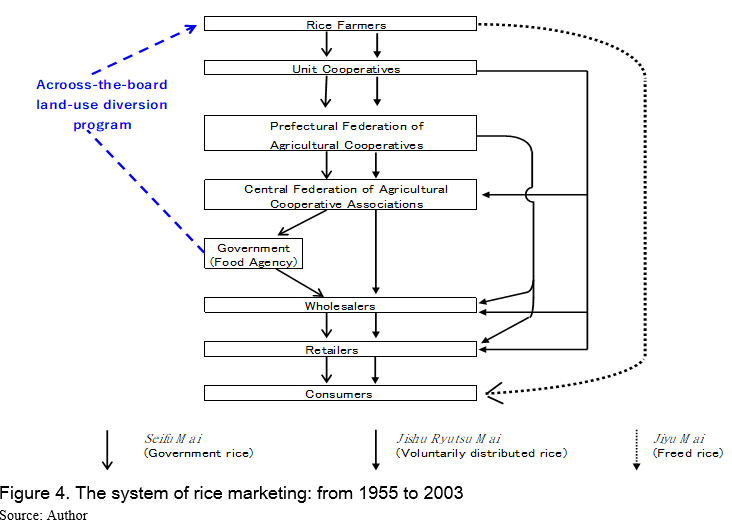

The new rice marketing system under the Staple Food Law is illustrated in Figure 4. Freed rice was legalized as unplanned traded rice. While government rice and voluntarily distributed rice were maintained as planned traded rice, regulations on market channels between rice traders were largely removed. In spite of such a large-scale revision, the rice market system continued to be called the Food Control System (probably because the Food Agency continued to be involved in rice marketing).

In September 2001, Jun-ichiro Koizumi, a known vigorous reformer based on the neoclassical economic thinking, came to power. He launched various deregulation policies during his term as Prime Minister (from September 2001 to September 2005). As a part of the Koizumi’s reform, the Staple Food Law had a major revision in 2004. By this revision, almost all regulations in rice marketing were removed. The terms, government rice, voluntarily distributed rice, freed rice disappeared from rice policy (and, accordingly, the rice market). The Food Agency was also dissolved. This revision of the Staple Food Law in 2003 was widely recognized as the end of the Food Control System.

Moreover, the across-the-board land-use diversion program was abolished. Instead, the government introduced a new system to curtail rice production. In this paper, it is hereinafter referred to as New Program. In the New Program, the government provides two options to farmers. One is not to grow rice in favor of receiving subsidies. The other is to grow rice freely instead of receiving subsidies. Unlike the across-the-board land-use diversion program, each farmer makes his or her own choice.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR OPENING A FUTURES MARKET FOR RICE

A futures market for any agricultural commodities had been closed during wartime and the early postwar period because the government employed food rationing. In the beginning of the 1950s, most of the food rationing systems was removed. Futures markets for agricultural commodities began in 1952 at the Tokyo Grain Exchange in Tokyo and the Osaka Dojima Exchange in Osaka[8]. Adzuki beans, soybeans, and wheat were listed at these commodities exchanges, but rice was not. This is because rice transactions (in terms of both volume and price) were controlled under the Food Control System.

The above-mentioned abolishment of the Food Control System in 2003 created an atmosphere conducive to the opening of a futures market for rice. Indeed, in 2005, the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange took such action. (note 8).

Those who run futures markets must follow procedures stipulated by the Commodity Futures Law. For futures market for agricultural commodities, the MAFF is the competent authority[9]. Institutions (such as the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange) intending to open a futures market for an agricultural commodity (in this case, rice) should submit a proposal for a temporary license to the MAFF. If the MAFF finds that the proposal satisfies the following two conditions, it issues a temporary license for futures market.

T1, the licensee will run the futures market fairly and transparently; and,

T2, the futures market will not disturb the government’s agricultural policy.

A temporary license is usually granted for a term of two or three years. During this period, the MAFF investigates the performance of the futures market and judges whether the temporary license should be replaced by a permanent license. The Commodity Futures Law stipulates the following two requirements for issuing a permanent license:

P1, the volume of trade at the futures market is sufficiently large; and,

P2, the futures market has positive effects on production and distribution of the agricultural commodity.

If the MAFF concludes that any of P1 and P2 is unsatisfied in the period of the temporary license, the futures market would be closed. If the MAFF needs more time to ascertain this, it extends the period of investigation by renewing the temporary license for another two or three years.

A problem is that these requirements (T1, T2, P1, and P2) are full of ambiguities. For example, the words of “fairly,” “transparently,” “disturb,” “sufficiently large,” and “promote” are unclear. Accordingly, there is a possibility that the MAFF becomes opportunistic, receiving informal (and/or implicit) pressures from politicians and the general public.

THE OPENING OF FUTURES MARKET FOR RICE IN 2011

On December 28, 2005, the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange jointly submitted a proposal for a temporary license for opening a futures market for rice. The Commodity Futures Law requires the MAFF to make the decision on whether to issue a temporary license within four months.

Previously, the MAFF always granted temporary licenses for futures market once it received a proposal. In addition, both the Tokyo Grain Exchange and Osaka Dojima Exchange had informal but close communications with the MAFF[10]. Thus, mass media expected that a temporary license would be issued. However, on March 28, 2006, the MAFF decided not to issue a temporary license.

On March 8, 2011, the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange submitted a joint proposal for a temporary license for a futures market. This time, the temporary license was granted and the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange opened futures markets for rice on August 8, 2011.

The MAFF did not explain why it decided favorably in 2011, but not in 2005. However, the Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu (2021b) provides useful underground information on the process of the MAFF’s decision making. The Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu (2021b) reported that the director general of the General Food Policy Bureau of the MAFF was responsible for the final decision on the issuance of temporary licenses. Interestingly, the same person was in the position both in 2005 and in 2011. The Editorial Board of Kome Ryutsu (2021b) concludes that if the MAFF routinely (or mechanically) applied the two requirements, T1 and T2 as mentioned earlier, to the proposal for a temporary license, there was no reason for the MAFF’s decision to change between 2005 and 2011. This implies the possibility that political pressure affected the MAFF’s decision making.

It should be noted that the Japanese general public has a negative perception on futures markets. In particular, since the burst of the bubble economy in the early 1990s, uninvited solicitations that cheated ordinary persons out of their savings has become a prevalent social problem. Commodities at futures markets have been occasionally used at uninvited solicitations. While this problem comes from uninvited solicitations instead of the futures market, the general public sometimes makes an erroneous conclusion that futures market is the root of all evils.

NOKYO’S OPPOSITION TO FUTURES TRADING FOR RICE

Nokyo repeatedly argues that Japan should not have a futures market for rice. Previously, Nokyo had enjoyed stable profits as a monopolistic rice collecting body under the Food Control System. However, the liberalization of rice market in 2003 drove Nokyo to fierce market competition, making it difficult to earn profits from rice collection. Thus, Nokyo pushed for the restoration of the government’s strict control on rice marketing. In other words, Nokyo tried to oppose to any attempts that promoted market competition. Even after the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange received a temporary license for rice futures market in 2011, the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperative Associations persuaded all the unit cooperatives not to participate in futures trading.

How much did Nokyo’s action affect the MAFF’s decision on futures market for rice? In considering this question, it would be useful to review the political relationship between Nokyo and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which was established in 1955 and had been almost entirely in power until 2009.

The LDP was regarded as the biggest conservative political party in Japan. In the 1950s, the agricultural sector had the largest proportion of Japan’s labor force. By designing pro-agriculture policies (such as rice price supports in the Food Control System), the LDP politicians drew support from farmers in elections. By organizing farmers nationwide, Nokyo functioned as one of the strongest voting groups for the LDP.

The total number of farmer votes has been declining since the 1950s due to the population migration from the agricultural to the commercial and industrial sectors[11]. However, Japan’s unique system helped Nokyo to maintain its importance as a voting group in elections for the members of the House of Representatives. The number of voters per representative was smaller in the rural areas than in the urban areas. More importantly, while each voter could cast only one vote, plural seats (usually between three and five based on the constituency) were allocated to a single constituency. This system is called a multi-seat constituency system. Under this system, the LDP needed to obtain multiple seats in a constituency in order to have a majority in the House of Representatives. Since Nokyo was good at allocating farmers’ votes among candidates from the LDP in each constituency, the LDP needed to collaborate with Nokyo in elections.

However, the election reform in the middle of 1990s changed the political structure. In 1994, the bill for the revision of the entire electoral system for the House of Representatives was passed by the Diet. The former multi-seat constituency system was replaced by a single-seat system. This meant that Nokyo’s strategy of allocating farmers’ votes to plural candidates from the LDP in the same constituency collapsed. Following this revision, the inequality of the value of a single vote was reduced by reducing the number of seats for the constituencies of the rural areas and increasing the seats for the constituencies in the urban areas. This also reduced the value of farmers’ (i.e., Nokyo members’) votes. As a result, while Nokyo continued to support the LDP after the electoral reform, its influence on the LDP became weaker. Individual LDP lawmakers who had received Nokyo’s support before the electoral reform may have remained sympathetic to Nokyo even after the electoral reform; however, such feelings would fade over time.

This author’s understanding is as follows. In 2005, when the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange submitted a proposal for a temporary license for opening a rice futures market, Nokyo’s influence was still strong enough to pressure the MAFF against issuing a license. However, in August 2009, the LDP lost in the general election and became an opposition party. In the election, by raising a slogan of “change,” the Democratic Party (DP) attracted voters and achieved a landslide victory. The DP had been the single ruling party until December 2012. Meanwhile, in designing economic policies, the DP government had been hardhearted to traditional voting groups for the LDP such as Nokyo. The Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries refused to meet Nokyo’s top officials, who wanted to have petitionary visits on agricultural policy. In addition, many agricultural subsidies were redesigned, becoming unfavorable to Nokyo. As such, the MAFF’s issuance of a temporary license for futures market in 2011 can be seen as one of the DP government’s hardline approaches to Nokyo.

The LDP came back to power at the end of 2012 under the leadership of Shinzo Abe, who had headed the LDP from September 2012 to June 2020. However, Nokyo continued to receive cold treatment from the administration, despite the return of the LDP to power. This was because Abe wanted to present himself to the general public as a reformer against the old guard. In fact, Nokyo had become already too weak to be called the old guard when the LDP came back to power in 2012, but the image of a politically powerful Nokyo still persisted among the general public. Thus, Nokyo was a good object for Abe to showcase his dauntless reformist attitude. In 2015, by revising the Agricultural Cooperative Law, Abe removed the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperative Associations from the Nokyo system. As of March 2022, while farmers are still allowed to participate in some political activities at Nokyo, it is no longer a key player in Japan’s agricultural political arena.

CLOSURE OF FUTURES MARKET FOR RICE IN 2021

In February 2013, as part of the derivative business society’s own reform, the Tokyo Grain Exchange was dissolved. The futures market for rice at the Tokyo Grain Exchange was transferred to the Osaka Dojima Exchange.

Since the opening of futures market for rice, the Osaka Dojima Exchange had been active in persuading the MAFF to replace the temporary license for futures market for rice with a permanent one. However, the MAFF postponed making its final decision by renewing the temporary license four times. Finally, in August 2021, the MAFF decided to close the futures market for rice by neither renewing the temporary license nor issuing a permanent license.

The Editorial Department of Kome Ryutsu (2021a) provides an interesting comparative study with the case of corn futures market. The Tokyo Grain Exchange started futures market for corn under a temporary license from the MAFF in April 1993. In April 1995, the temporary license was replaced by a permanent one. The Editorial Department of Kome Ryutsu (2021a) compares the performance of futures market for rice under the temporary license (i.e., from August 2011 to August 2021) and the performance of futures market for corn under the temporary license (i.e., from April 1993 to April 1995). It was concluded that the performance of the futures market for rice under the temporary license was satisfactory enough for a permanent license to be granted. Still, the MAFF decided not to issue a permanent license for rice, implying the possibility of some informal pressure affecting the MAFF’s decision making.

The discussion in the previous section implies that it is unlikely that Nokyo’s opposition against the futures market influenced the MAFF’s decision after the LDP’s return to power in 2012. Instead, it is likely the general public’s bad image of futures markets may have affected the LDP government’s decision. It is true that uninvited solicitations that cheat many citizens out of their savings in futures market is a serious social problem. Despite this, the series of such tragedies should logically be regarded as a problem of the uninvited solicitation (not of futures market). Unfortunately, politicians tend to exploit these to showcase a reformer attitude and unduly puts blame on the futures market.

The closure of futures market for rice disappointed those who were participating in futures trading (including farmers and rice merchandizers). In addition, According to Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu (2021c), the closure of the futures market made negative impacts on the real market spot market for rice: i.e., the fluctuations of spot price for rice became more violent after the closure of the futures market for rice.

CONCLUSION

For more than 60 years until 2004, Japan’s rice market had been under strict control of the government. In those days, rice price did not reflect supply–demand conditions. However, in 2004, the government removed most of its control on rice marketing. This motivated the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange to start futures market for rice. However, Japanese general public’s negative perception of the futures market was a major problem. As a result, the futures market for rice that opened in 2011 under temporary license from the MAFF, was eventually closed in 2021. It is possible that a more nuanced understanding of the futures market by the Japanese general public could have resulted in this market remaining active until the present.

REFERENCES

Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu, 2021a, “Hatsu Kuria shita Yoken Jubun-na.Torihikiryo (The Volume of Futures Trading Reached A Satisfactory Level) Kome to Ryutsu Vol. 46, No. 4.

Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu, 2021b, “Kakuritsu wa Gobugobu to Shitekubeki (It is a Toss-up Whether the Government Issues a Permanent License for the Futures Market for Rice),″Kome to Ryutsu Vol. 46, No. 5.

Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu, 2021c, “Shijo Fuzai no Beika (Rice Price without the Market Mechanizm),″ Kome to Ryutsu Vol. 46, No. 10.

Hayami, Y., and Y. Godo, 1997, “Economics and Politics of Rice Policy in Japan: A Perspective on the Uruguay Round” in Regionalism versus Multilateral Trade Agreements, eds. T. Ito and A. Krueger, University of Chicago Press.

[1] Since the 8th century, many historical books call Japan “the Land of Abundant Reed Plains and Rice Field,” which became its nickname.

[3] While China and Japan had been hostile to each other for nearly 10 years until Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, there was no official declaration of war between the two countries. Thus, it is difficult to determine the exact date when Japan’s full-scale-militarism started. Currently, a majority of historians consider that the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937 as the beginning of the full-scale militarism in Japan.

[4] Rice price hike was attributable to the rice shortage, and the closure of the Osaka Dojima Market could not solve the problem of rice price hike. However, the Dojima Rice Market was falsely accused for manipulating rice price.

[5] Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries was named Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry until 1978. For the sake of simplicity, this paper calls it Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries for the period before the renaming.

[6] According to the GATT Uruguay Round Final Agreements, Japan started importing rice in 1995. However, because of the Japanese government’s high trade barrier against foreign rice, the total imports of rice accounts for only around 7% of total rice consumption.

[7] Hayami and Godo (1997) provides their estimates on the cartel effects of the across-the-board land use diversion program.

[8] Until 2012, Osaka Dojima Exchange was named Kansai Commodity Exchange. For the sake of simplicity, this paper calls it Osaka Dojima Exchange for pre-2012 years, as well.

[9] For the futures market for non-agricultural commodities (e.g., aluminum, oil, and precious metals), the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is the competent authority.

[10] As of 2005, the chairpersons of the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange were former MAFF officials. Oftentimes, former MAFF officials keep informal but close communications with the MAFF even after their retirement from the MAFF.

[11] According to Japan’s population census, the number of farm households hit a peak in 1950.

Futures Market for Rice in Japan

ABSTRACT

Japan has a unique place in the history of futures trading, as the Dojima Rice Market in Osaka, established in 1697 and authorized in 1730, is said to be the first case in the world that a futures market for any commodity was operated under the official government permission. This indicates the use of rice as quasi-money in the Tokugawa Shogunate period. Even after the Meiji Restoration (1868), the Dojima Rice Market had been an active social infrastructure. However, the government closed the Dojima Rice Market in 1939 when the government employed strict controls on rice marketing under a serious food shortage resulting from Japan’s expansion of military action. The government’s control on rice marketing continued into the American Army’s occupation immediately after the Second World War due to the continuing severe food shortage. While Japan regained sovereignty and became food abundant in the 1950s, the government continued its control on rice marketing by redirecting its intentions toward supporting farmers’ income. In 2003, as a part of the government’s deregulation policy, the government abolished most of its control on rice marketing. This created an atmosphere for re-opening the futures market for rice. The biggest obstacle to such a market is a prevailing negative public perception of futures markets. For years, dishonest traders made uninvited solicitations, using commodity futures market to cheat the public. This became a serious social problem. While the futures market for rice opened in 2011 under a temporary license from the government, it was eventually closed in 2021 although there were no uninvited solicitations at the futures market for rice between 2011 and 2021. If the Japanese general public had proper understanding on merits of futures markets, the rice futures market would have been kept active even now.

Keywords: Agricultural Cooperative Law, Commodity Futures Law, Food Control Law, Liberal Democratic Party, Staple Food Law

INTRODUCTION

A futures market for any commodity possesses merits on the free market economy (or a capitalist society). Thus, a futures market provides an opportunity for stabilizing income for those who want to avoid the risk of leaps and plunges in commodity prices. In addition, it provides an opportunity of high-risk but high-return in investments for those who can afford to take the risk of price fluctuations. Moreover, by observing the pricing results at a futures market, businesspersons and researchers share information on demand-supply condition of the commodity.

In spite of these merits, on August 7, 2021, the Japanese government decided to close the rice futures market. Why did the Japanese government make such a decision? By reviewing the long history of Japan’s rice market policy, this paper aims to explain the reason behind the closure of the country’s rice futures market.

JAPAN’S RICE POLICY FROM THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE PERIOD TO THE MIDDLE OF THE 1930s

Together with corn and wheat, rice is one of the three major crops in the world. For people in monsoon Asia, rice is an especially important crop. Japan is not an exception. Since ancient times, rice has been the staple food of the Japanese[1].

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s foremost priority was promotion of rice production. Farmers were not allowed to plant any crops other than rice unless they received special permission.

While the Tokugawa Shogunate employed the gold and silver bimetallism, rice also functioned as quasi-money. For example, farmers were obliged to pay tax with rice. Salaries of samurai were paid with rice. Merchandizers settle accounts by exchanging certificates of rice deposits in warehouses. The wealth (and economic ranking) of a han (feudal domain in the Tokugawa Shogunate period) was measured by how much rice a han was able to produce.

In the Tokugawa Shogunate period, Dojima, a hinterland of a major port in Osaka, became a prosperous and busy business district. In 1697, merchandizers in Dojima set up a permanent market for rice futures trading on their own. This was called the Dojima Rice Market. In 1730, recognizing the social merits of futures trading at the Dojima Rice Market, the Tokugawa Shogunate authorized the Dojima Rice Market by issuing a formal certificate, recognizing it as a social infrastructure. This is believed to be the first case in the world that a futures market obtained approval from the national authorities (or the ruler of the country)[2].

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 marked the turning point of Japanese society. The feudalistic authorities of the Tokugawa Shogunate collapsed and a new central government, called the Meiji government, started ruling over Japan. Meiji is the name of an imperial era from 1868 to 1912. A major objective of the Meiji government was the promotion of capitalistic economic development. To do so, the Meiji government abolished many of old customs. For example, the Meiji government required farmers to pay tax in cash, instead of paying with rice).

The Meiji government recognized that futures trading for rice was favorable for Japan’s capitalistic economic development. Thus, the Meiji government also made the Dojima Rice Market an official market. As the Meiji Emperor passed away in 1912, the imperial era name changed from Meiji to Taisho. When the Taisho Emperor passed away in 1926, the imperial era name changed from Taisho to Showa. Until around the middle of the 1930s, and through two name changes of the imperial period as mentioned above, the Japanese government’s top priority, i.e., capitalistic economic development, remained unchanged. Futures trading continued actively at the Dojima Rice Market, and the daily pricing results at the Dojima Rice Market had been used as a key indicator of the Japanese economy among businesspersons, researchers, and politicians.

RICE POLICY IN THE WARTIME PERIOD

Japan’s full-scale militarization, which started in the middle of 1930s brought a drastic change in the rice market[3]. According to the expansion of the war fronts, the Japanese government conscripted more and more young farmers into the army. In addition, the Japanese government prioritized the distribution of raw materials to military uses, instead of civilian uses such as equipment and materials for farming. As a result, rice became in short supply. Rice prices on the futures and real markets spiked to an intolerable level for the general public. As a part of the Japanese government’s reaction to the rice shortage, the government ordered the closure of the Dojima Rice Market in 1939[4].

In addition, as a part of the general mobilization policy, the government established a nationwide farmers’ organization, called Nogyokai, in 1943. Each municipality had to have a local office of Nogyokai, and the mayor of the municipality appointed a director. Every farmer was obliged to be part of the local office of Nogyokai in his or her municipality.

Using the Nogyokai system, the Japanese government established the government-laid rice marketing system, called Food Control System. All the rice marketing was controlled by the Food Distribution Corporation, a government-affiliated corporation. Every farmer sold all the rice in excess of his or her family’s consumption to the Food Distribution Corporation through Nogyokai. Then, all the rice was distributed to consumers through the channels designated by the Food Distribution Corporation. The Food Control Law provided the legal basis for the Food Control System.

RICE POLICY UNDER THE OCCUPATION AUTHORITIES’ RULE

In August 1945, Japan announced an unconditional surrender to the Allied Powers led by the United States. For four years and six months since then, the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) administered Japan. The top agenda of the GHQ’s administration was to reform Japan into a democratic country that is aligned with the Western (or anti-Communist) bloc.

Treatment of Nogyokai was one of the biggest problems for the GHQ. Two contrasting views on Nogyokai prevailed: One view was that Nogyokai should be maintained because Nogyokai played a key role of procuring rice from farmers in the Food Control System, which was essential in keeping Japanese people fed in the face of limited rice production capacity. Another view was that, since Nogyokai was a part of the previous militaristic regime, Nogyokai should be dissolved in order to democratize Japanese society.

The GHQ’s decision was the establishment a new farmers’ organization, called Nokyo, taking the place of Nogyokai in the Food Control System. The legal basis for Nokyo was (and still is) the Agricultural Cooperative Law promulgated in November 1947. Nogyokai was dissolved in August 1948.

In 1949, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) reorganized the entire departmental system[5]. As part of the revision, the Food Agency was established as an extra-ministerial bureau responsible for the Food Control System. This was the same responsibility that the Food Distribution Corporation had borne before the GHQ reined over Japan).

In 1951, Japan regained its sovereignty and the GHQ was dissolved. In the 1950s, the manufacturing industry grew faster than the agricultural sector then, the income gap between farmers in rural areas and salaried workers in urban areas increased to a politically intolerable level.

Japan recovered from the war damages, and food supply became sufficient in the 1950s. The timing was thought to be right for abolishing the Food Control System. However, the government kept the Food Control System by changing its purpose—to support farmers’ income level. The following sections show how farmers’ income was supported through the Food Control System.

THE NOKYO SYSTEM

Before talking more about the Food Control System, it should be useful to have a quick review of the Nokyo system.

Nokyo had (and still has) two faces: as a democratic organization whereby farmers work together for mutual economic benefits; and, as de facto sub-governmental body, which collaborates with the government in implementing the government’s agricultural policy.

The Nokyo system has a three-tier structure. Unit cooperatives in villages, towns, and cities constitute the first level. The unit cooperatives are in direct contact with farmers; each unit cooperative has its own jurisdiction and does not overlap with any other jurisdiction. Although there is no legal requirement, most farmers join Nokyo as regular members of the unit cooperatives where they live.

The second tier consists of two associations in each prefecture. One is the prefectural federation of agricultural cooperatives, which is engaged in economic activities such as joint shipping of agricultural commodities. The other is the prefectural union of agricultural cooperatives, which are engaged in political activities such as campaign for import tariffs on foreign agricultural products. All the unit cooperatives in each prefecture belong to both the prefectural union of agricultural cooperatives and prefectural federation of agricultural cooperatives (Japan consists of 47 prefectures). At the third tier, Nokyo has two associations (as described later, one of them was dissolved after the revision of the Agricultural Cooperative Law in 2015): the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, which integrates the 47 prefectural unions of agricultural cooperatives, and the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, which integrates the 47 prefectural federations of agricultural cooperatives. As such, Nokyo can be seen as a mammoth system for farmers’ economic and political activities. However, as mentioned later, the revision of the Agricultural Cooperative Law in 2015 deprived Nokyo of political power.

RICE POLICY IN THE 1960s

The Food Control System had been effective until 2003. During this period, it had occasionally received revisions. Major revisions took place twice: the first in 1970 and the second in 1994.

Figure 1 shows the structure of Food Control System until 1970. Farmers were obliged to supply rice to unit cooperatives in their villages. Then, through prefectural federations of agricultural cooperatives and the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, the Food Agency procured rice. Distribution channels from the Food Agency to consumers were also strictly regulated. The wholesalers and retailers of rice need licenses from the prefectural governors. The timing and volume of transaction between wholesalers and retailers were also controlled by the Food Agency.

The Food Agency’s selling and procurement prices were determined before the harvest season. In addition, the marketing margins for unit agricultural cooperatives, prefectural federation of agricultural cooperatives, the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, rice wholesalers, and rice retailers were also fixed by the Food Agency. In sum, the Food Agency controlled all rice transactions, from farmers to consumers.

In the early 1950s, Japan’s miraculous high-speed economic growth started. The annual economic growth rate in this period was nearly 10%. In particular, the manufacturing sector prospered by borrowing advanced technologies from European and North American countries. While agricultural productivity increased, the growth rate of the agriculture sector was much lower than that of the manufacturing sector. In addition, demands for manufactured commodities grew faster than that for agricultural commodities. As a result, the income gap – and living conditions – between farm households and their urban counterparts widened and became one of the biggest political concerns in the late 1950s.

In 1960, the government employed a unique rice price-determination formula called Production Cost Compensation Program. In this formula, the government procurement price was determined in a way that the cost of rice production is covered, including unpaid family labor which was estimated as the wage rate in the manufacturing sector. Based on this formula, the government raised its procurement price for rice corresponding to the rapid wage increases in the manufacturing sector. Accordingly, the ratio between domestic rice price and international price increased sharply. Since the government prohibited rice imports, foreign rice did not flow into Japan[6].

The government’s high procurement price stimulated rice production. Although the government set rice sales price lower than its procurement price, rice stocks accumulated. This is because the eating habits of Japanese consumers have become more western; consequently demand for rice decreased at an unexpectedly high speed. As a result, the burden of national budgets for rice price support increased in two ways. First, since the government sold rice with negative margin, the government allocated special budgets to fill the gap between sales price and procurement price. Second, the government bore the cost of rice storage (including disposal costs of old rice).

RICE POLICY IN THE 1970s

The national budgetary burden for rice price support increased to a politically intolerable level at the end of the 1960s. In addition, the average income of farmers exceeded that of salaried workers in urban areas around 1970 as a result of the government’s rice price support policy and increased income from off-farm employment.

As such, around 1970 seemed an appropriate moment for the government to suspend rice price support and liberalize rice marketing by abandoning the Food Control System. However, that was not what the government chose to do. Instead, the government launched two measures to reduce the fiscal expenditure on rice marketing. First, the government allowed rice wholesalers to purchase rice directly from the Central Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations, bypassing the Food Agency. This type of rice was called voluntarily distributed rice (Jishu Ryutu Mai in Japanese). This new system encouraged production of high-quality rice (good taste rice) that could not be priced adequately in the procurement of the Food Agency.

The rice purchased by the Food Agency was called government rice (Seifu Mai in Japanese). Besides government rice and voluntarily distributed rice, some rice was illegally distributed out of the Food Control Law. Such rice was called freed rice (Jiyu Mai in Japanese).

It should be noted that consumers’ requests on the quality of rice became more and more diversified in the 1960s as consumers became more discriminating in their tastes for rice. However, the Food Control System was too strict, even after the introduction of voluntarily distributed rice. Thus, the government often connived with those engaged in buying and/or selling rice out of the framework of the Food Control System. Figure 2 illustrates the system of the Japanese rice market after 1970.

Another measure for curbing the national budgetary burden was the across-the-board land use diversion program. This program can be seen as a government-led rice production cartel. The government at first set the target acreage that should be diverted from rice planting so as to prevent excess supply of rice. With the collaboration of Nokyo, the target acreage was allocated into all the villages. All farmers in the villages collaborated to achieve the allocated acreages.

While the government provided financial support to rice farmers according to the acreage diverted from rice planting, it did not fully compensate the reduction of rice income at the microeconomic level. But, in the aggregate, the cartel effect of the across-the-board land use diversion program benefitted rice farmers as high rice price was maintained[7]. As a result, the target acreage is achieved at nearly 100 % every year.

While the across-the-board land use diversion program was originally introduced in 1970 as an emergency (or temporary) countermeasure against the excess accumulation of old rice stock, it had continued for more than 30 years since then.

LIBERALIZATION OF RICE MARKETING

By the early 1990s, the percentage of government rice decreased to less than 5% in the rice market (Figure 3). In addition, although the legal basis for freed rice was not secure, the percentage of freed rice as well as that of voluntarily distributed rice kept increasing. Responding to this situation, the government submitted a new law, called Staple Food Law, to the Diet in 1994. The Staple Food Law came into force in 1995 and the Food Control Law was abolished then.

The new rice marketing system under the Staple Food Law is illustrated in Figure 4. Freed rice was legalized as unplanned traded rice. While government rice and voluntarily distributed rice were maintained as planned traded rice, regulations on market channels between rice traders were largely removed. In spite of such a large-scale revision, the rice market system continued to be called the Food Control System (probably because the Food Agency continued to be involved in rice marketing).

In September 2001, Jun-ichiro Koizumi, a known vigorous reformer based on the neoclassical economic thinking, came to power. He launched various deregulation policies during his term as Prime Minister (from September 2001 to September 2005). As a part of the Koizumi’s reform, the Staple Food Law had a major revision in 2004. By this revision, almost all regulations in rice marketing were removed. The terms, government rice, voluntarily distributed rice, freed rice disappeared from rice policy (and, accordingly, the rice market). The Food Agency was also dissolved. This revision of the Staple Food Law in 2003 was widely recognized as the end of the Food Control System.

Moreover, the across-the-board land-use diversion program was abolished. Instead, the government introduced a new system to curtail rice production. In this paper, it is hereinafter referred to as New Program. In the New Program, the government provides two options to farmers. One is not to grow rice in favor of receiving subsidies. The other is to grow rice freely instead of receiving subsidies. Unlike the across-the-board land-use diversion program, each farmer makes his or her own choice.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR OPENING A FUTURES MARKET FOR RICE

A futures market for any agricultural commodities had been closed during wartime and the early postwar period because the government employed food rationing. In the beginning of the 1950s, most of the food rationing systems was removed. Futures markets for agricultural commodities began in 1952 at the Tokyo Grain Exchange in Tokyo and the Osaka Dojima Exchange in Osaka[8]. Adzuki beans, soybeans, and wheat were listed at these commodities exchanges, but rice was not. This is because rice transactions (in terms of both volume and price) were controlled under the Food Control System.

The above-mentioned abolishment of the Food Control System in 2003 created an atmosphere conducive to the opening of a futures market for rice. Indeed, in 2005, the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange took such action. (note 8).

Those who run futures markets must follow procedures stipulated by the Commodity Futures Law. For futures market for agricultural commodities, the MAFF is the competent authority[9]. Institutions (such as the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange) intending to open a futures market for an agricultural commodity (in this case, rice) should submit a proposal for a temporary license to the MAFF. If the MAFF finds that the proposal satisfies the following two conditions, it issues a temporary license for futures market.

T1, the licensee will run the futures market fairly and transparently; and,

T2, the futures market will not disturb the government’s agricultural policy.

A temporary license is usually granted for a term of two or three years. During this period, the MAFF investigates the performance of the futures market and judges whether the temporary license should be replaced by a permanent license. The Commodity Futures Law stipulates the following two requirements for issuing a permanent license:

P1, the volume of trade at the futures market is sufficiently large; and,

P2, the futures market has positive effects on production and distribution of the agricultural commodity.

If the MAFF concludes that any of P1 and P2 is unsatisfied in the period of the temporary license, the futures market would be closed. If the MAFF needs more time to ascertain this, it extends the period of investigation by renewing the temporary license for another two or three years.

A problem is that these requirements (T1, T2, P1, and P2) are full of ambiguities. For example, the words of “fairly,” “transparently,” “disturb,” “sufficiently large,” and “promote” are unclear. Accordingly, there is a possibility that the MAFF becomes opportunistic, receiving informal (and/or implicit) pressures from politicians and the general public.

THE OPENING OF FUTURES MARKET FOR RICE IN 2011

On December 28, 2005, the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange jointly submitted a proposal for a temporary license for opening a futures market for rice. The Commodity Futures Law requires the MAFF to make the decision on whether to issue a temporary license within four months.

Previously, the MAFF always granted temporary licenses for futures market once it received a proposal. In addition, both the Tokyo Grain Exchange and Osaka Dojima Exchange had informal but close communications with the MAFF[10]. Thus, mass media expected that a temporary license would be issued. However, on March 28, 2006, the MAFF decided not to issue a temporary license.

On March 8, 2011, the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange submitted a joint proposal for a temporary license for a futures market. This time, the temporary license was granted and the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange opened futures markets for rice on August 8, 2011.

The MAFF did not explain why it decided favorably in 2011, but not in 2005. However, the Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu (2021b) provides useful underground information on the process of the MAFF’s decision making. The Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu (2021b) reported that the director general of the General Food Policy Bureau of the MAFF was responsible for the final decision on the issuance of temporary licenses. Interestingly, the same person was in the position both in 2005 and in 2011. The Editorial Board of Kome Ryutsu (2021b) concludes that if the MAFF routinely (or mechanically) applied the two requirements, T1 and T2 as mentioned earlier, to the proposal for a temporary license, there was no reason for the MAFF’s decision to change between 2005 and 2011. This implies the possibility that political pressure affected the MAFF’s decision making.

It should be noted that the Japanese general public has a negative perception on futures markets. In particular, since the burst of the bubble economy in the early 1990s, uninvited solicitations that cheated ordinary persons out of their savings has become a prevalent social problem. Commodities at futures markets have been occasionally used at uninvited solicitations. While this problem comes from uninvited solicitations instead of the futures market, the general public sometimes makes an erroneous conclusion that futures market is the root of all evils.

NOKYO’S OPPOSITION TO FUTURES TRADING FOR RICE

Nokyo repeatedly argues that Japan should not have a futures market for rice. Previously, Nokyo had enjoyed stable profits as a monopolistic rice collecting body under the Food Control System. However, the liberalization of rice market in 2003 drove Nokyo to fierce market competition, making it difficult to earn profits from rice collection. Thus, Nokyo pushed for the restoration of the government’s strict control on rice marketing. In other words, Nokyo tried to oppose to any attempts that promoted market competition. Even after the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange received a temporary license for rice futures market in 2011, the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperative Associations persuaded all the unit cooperatives not to participate in futures trading.

How much did Nokyo’s action affect the MAFF’s decision on futures market for rice? In considering this question, it would be useful to review the political relationship between Nokyo and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which was established in 1955 and had been almost entirely in power until 2009.

The LDP was regarded as the biggest conservative political party in Japan. In the 1950s, the agricultural sector had the largest proportion of Japan’s labor force. By designing pro-agriculture policies (such as rice price supports in the Food Control System), the LDP politicians drew support from farmers in elections. By organizing farmers nationwide, Nokyo functioned as one of the strongest voting groups for the LDP.

The total number of farmer votes has been declining since the 1950s due to the population migration from the agricultural to the commercial and industrial sectors[11]. However, Japan’s unique system helped Nokyo to maintain its importance as a voting group in elections for the members of the House of Representatives. The number of voters per representative was smaller in the rural areas than in the urban areas. More importantly, while each voter could cast only one vote, plural seats (usually between three and five based on the constituency) were allocated to a single constituency. This system is called a multi-seat constituency system. Under this system, the LDP needed to obtain multiple seats in a constituency in order to have a majority in the House of Representatives. Since Nokyo was good at allocating farmers’ votes among candidates from the LDP in each constituency, the LDP needed to collaborate with Nokyo in elections.

However, the election reform in the middle of 1990s changed the political structure. In 1994, the bill for the revision of the entire electoral system for the House of Representatives was passed by the Diet. The former multi-seat constituency system was replaced by a single-seat system. This meant that Nokyo’s strategy of allocating farmers’ votes to plural candidates from the LDP in the same constituency collapsed. Following this revision, the inequality of the value of a single vote was reduced by reducing the number of seats for the constituencies of the rural areas and increasing the seats for the constituencies in the urban areas. This also reduced the value of farmers’ (i.e., Nokyo members’) votes. As a result, while Nokyo continued to support the LDP after the electoral reform, its influence on the LDP became weaker. Individual LDP lawmakers who had received Nokyo’s support before the electoral reform may have remained sympathetic to Nokyo even after the electoral reform; however, such feelings would fade over time.

This author’s understanding is as follows. In 2005, when the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange submitted a proposal for a temporary license for opening a rice futures market, Nokyo’s influence was still strong enough to pressure the MAFF against issuing a license. However, in August 2009, the LDP lost in the general election and became an opposition party. In the election, by raising a slogan of “change,” the Democratic Party (DP) attracted voters and achieved a landslide victory. The DP had been the single ruling party until December 2012. Meanwhile, in designing economic policies, the DP government had been hardhearted to traditional voting groups for the LDP such as Nokyo. The Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries refused to meet Nokyo’s top officials, who wanted to have petitionary visits on agricultural policy. In addition, many agricultural subsidies were redesigned, becoming unfavorable to Nokyo. As such, the MAFF’s issuance of a temporary license for futures market in 2011 can be seen as one of the DP government’s hardline approaches to Nokyo.

The LDP came back to power at the end of 2012 under the leadership of Shinzo Abe, who had headed the LDP from September 2012 to June 2020. However, Nokyo continued to receive cold treatment from the administration, despite the return of the LDP to power. This was because Abe wanted to present himself to the general public as a reformer against the old guard. In fact, Nokyo had become already too weak to be called the old guard when the LDP came back to power in 2012, but the image of a politically powerful Nokyo still persisted among the general public. Thus, Nokyo was a good object for Abe to showcase his dauntless reformist attitude. In 2015, by revising the Agricultural Cooperative Law, Abe removed the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperative Associations from the Nokyo system. As of March 2022, while farmers are still allowed to participate in some political activities at Nokyo, it is no longer a key player in Japan’s agricultural political arena.

CLOSURE OF FUTURES MARKET FOR RICE IN 2021

In February 2013, as part of the derivative business society’s own reform, the Tokyo Grain Exchange was dissolved. The futures market for rice at the Tokyo Grain Exchange was transferred to the Osaka Dojima Exchange.

Since the opening of futures market for rice, the Osaka Dojima Exchange had been active in persuading the MAFF to replace the temporary license for futures market for rice with a permanent one. However, the MAFF postponed making its final decision by renewing the temporary license four times. Finally, in August 2021, the MAFF decided to close the futures market for rice by neither renewing the temporary license nor issuing a permanent license.

The Editorial Department of Kome Ryutsu (2021a) provides an interesting comparative study with the case of corn futures market. The Tokyo Grain Exchange started futures market for corn under a temporary license from the MAFF in April 1993. In April 1995, the temporary license was replaced by a permanent one. The Editorial Department of Kome Ryutsu (2021a) compares the performance of futures market for rice under the temporary license (i.e., from August 2011 to August 2021) and the performance of futures market for corn under the temporary license (i.e., from April 1993 to April 1995). It was concluded that the performance of the futures market for rice under the temporary license was satisfactory enough for a permanent license to be granted. Still, the MAFF decided not to issue a permanent license for rice, implying the possibility of some informal pressure affecting the MAFF’s decision making.

The discussion in the previous section implies that it is unlikely that Nokyo’s opposition against the futures market influenced the MAFF’s decision after the LDP’s return to power in 2012. Instead, it is likely the general public’s bad image of futures markets may have affected the LDP government’s decision. It is true that uninvited solicitations that cheat many citizens out of their savings in futures market is a serious social problem. Despite this, the series of such tragedies should logically be regarded as a problem of the uninvited solicitation (not of futures market). Unfortunately, politicians tend to exploit these to showcase a reformer attitude and unduly puts blame on the futures market.

The closure of futures market for rice disappointed those who were participating in futures trading (including farmers and rice merchandizers). In addition, According to Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu (2021c), the closure of the futures market made negative impacts on the real market spot market for rice: i.e., the fluctuations of spot price for rice became more violent after the closure of the futures market for rice.

CONCLUSION

For more than 60 years until 2004, Japan’s rice market had been under strict control of the government. In those days, rice price did not reflect supply–demand conditions. However, in 2004, the government removed most of its control on rice marketing. This motivated the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange to start futures market for rice. However, Japanese general public’s negative perception of the futures market was a major problem. As a result, the futures market for rice that opened in 2011 under temporary license from the MAFF, was eventually closed in 2021. It is possible that a more nuanced understanding of the futures market by the Japanese general public could have resulted in this market remaining active until the present.

REFERENCES

Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu, 2021a, “Hatsu Kuria shita Yoken Jubun-na.Torihikiryo (The Volume of Futures Trading Reached A Satisfactory Level) Kome to Ryutsu Vol. 46, No. 4.

Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu, 2021b, “Kakuritsu wa Gobugobu to Shitekubeki (It is a Toss-up Whether the Government Issues a Permanent License for the Futures Market for Rice),″Kome to Ryutsu Vol. 46, No. 5.

Editorial Department of Kome to Ryutsu, 2021c, “Shijo Fuzai no Beika (Rice Price without the Market Mechanizm),″ Kome to Ryutsu Vol. 46, No. 10.

Hayami, Y., and Y. Godo, 1997, “Economics and Politics of Rice Policy in Japan: A Perspective on the Uruguay Round” in Regionalism versus Multilateral Trade Agreements, eds. T. Ito and A. Krueger, University of Chicago Press.

[1] Since the 8th century, many historical books call Japan “the Land of Abundant Reed Plains and Rice Field,” which became its nickname.

[2] Asahi Shimbun, ‘Japan ends 300 years of trading rice futures,’ dated August 7. 2021 [downloaded on 28 January 2022], available at https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14413055.

[3] While China and Japan had been hostile to each other for nearly 10 years until Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, there was no official declaration of war between the two countries. Thus, it is difficult to determine the exact date when Japan’s full-scale-militarism started. Currently, a majority of historians consider that the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937 as the beginning of the full-scale militarism in Japan.

[4] Rice price hike was attributable to the rice shortage, and the closure of the Osaka Dojima Market could not solve the problem of rice price hike. However, the Dojima Rice Market was falsely accused for manipulating rice price.

[5] Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries was named Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry until 1978. For the sake of simplicity, this paper calls it Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries for the period before the renaming.

[6] According to the GATT Uruguay Round Final Agreements, Japan started importing rice in 1995. However, because of the Japanese government’s high trade barrier against foreign rice, the total imports of rice accounts for only around 7% of total rice consumption.

[7] Hayami and Godo (1997) provides their estimates on the cartel effects of the across-the-board land use diversion program.

[8] Until 2012, Osaka Dojima Exchange was named Kansai Commodity Exchange. For the sake of simplicity, this paper calls it Osaka Dojima Exchange for pre-2012 years, as well.

[9] For the futures market for non-agricultural commodities (e.g., aluminum, oil, and precious metals), the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is the competent authority.

[10] As of 2005, the chairpersons of the Tokyo Grain Exchange and the Osaka Dojima Exchange were former MAFF officials. Oftentimes, former MAFF officials keep informal but close communications with the MAFF even after their retirement from the MAFF.

[11] According to Japan’s population census, the number of farm households hit a peak in 1950.