ABSTRACT

Philippine native pig meat is seen as a healthy alternative to commercial pig meat in the market and as a lucrative source of income for producers. However, despite the development of the country’s native industry, the goal of developing the native pig industry has not been achieved over time because several pig producers are still reluctant in producing native pigs. This study identified the marketing participants of native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan; described the marketing practices and strategies employed by the native pig raisers and intermediaries; determined the product and geographic flows of native pigs; and analyzed the cost and returns in marketing native pigs. A total of 106 market participants were interviewed in this study, including 30 native pig raisers, 12 traders, 11 wholesaler-retailers, 11 retailers, 11 processors, and 30 consumers. There were eight identified marketing channels in marketing native pigs in Sta. Maria but this study only discussed the two most common marketing channels used per season. Based on the study, the native pig raisers in Sta. Maria bought their material inputs from Malolos and Meycauayan. Meanwhile, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and retailers can be found in Sta. Maria and San Jose del Monte, and processors in Sta. Maria, San Jose del Monte, and Norzagaray, and Fairview, Quezon City. The practices employed by these key players include handling, transporting, slaughtering/butchering, packaging, storing, and processing. Results also showed that the average profit of native pig raisers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors differ depending on the season and marketing channel used.

Keywords: native, pigs, marketing, season

INTRODUCTION

Pigs, scientifically known as Sus scrofa domesticus, is the major source of protein to Filipinos, as it provides about 60% of the total animal meat consumption of Filipinos (Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development [DOST-PCAARRD], 2016). In 2017, the Philippine pig industry has contributed significantly to the world’s pig production; it ranked as the third top-pig producer in Asia, and eighth in the world. It is also the second-largest contributor to the total value of agricultural production in the country, contributing 18.28%, with a gross value of US$3.80 billion at current prices. The progress in the country’s pig industry is also notable since the hog inventory of the country went up to 12.71 million heads in 2018. This is a 0.83% increase in the country’s pig production as compared to 12.6 million pig production in 2017 (Philippine Statistics Authority [PSA], 2019). Moreover, according to the PSA, the country’s pig industry is dominated by backyard producers, which constitutes approximately 65% of the total production. Among the major hog-producing provinces in the Philippines, Cebu had the highest number of slaughtered hogs in 2018 with 908,114 heads slaughtered, followed by the province of Rizal (755,733), Pampanga (681,238) and Bulacan (673,397).

In 2011, Sta. Maria is classified as one of the top hog-producing municipalities in Bulacan (Bulacan Provincial Agriculture Office, 2012, as cited by Aspile et al., 2016). Sta. Maria has a generally warm climatic condition with average annual temperatures suitable for pig production (Aspile et al., 2016). It has also a relatively short distance away from market centers in the Philippines like Divisoria, which is just 35 kilometers away, and Pioneer Street Market, which is just 42 kilometers away. Because of these, Sta. Maria is deemed to have great potential in the expansion of backyard hog raising and native pig production.

One of the common breeds of pigs raised in backyard farms is the Philippine native pigs (Sus scrofa philippinensis). It is a small black pig with straight to low-set back and short legs and has a long snout and small, and erect ears (Manipol et al., 2014). This breed can be classified into two varieties called Ilocos and Jalajala, which are used in the development of other breeds such as Berkjala, Diani, Kaman, Koronadel, and Libtong. At present, it has four recognized species that may have evolved with the environment of the Philippine archipelago- Philippine warty pigs, Visayan warty pigs, Mindoro warty pigs, and Palawan bearded pigs (Mason, 1996).

Since Philippine native pigs are well-adapted to the country’s environmental condition, they do not require expensive housing and care, which makes them easier and cheaper to raise than commercial breeds (Guerrero III, 2016). Similarly, the Bureau of Animal Industry (2010) stated that raising a native pig incurs lower maintenance cost as it thrives well on locally-available feeds, and can be raised without the use of chemical inputs. Moreover, the native pig is also known to have good mothering ability and to be very prolific in terms of production (Mason, 1996).

Given its leaner and tastier meat and crispier roasted skin, native pigs are also being processed into lechon, a traditional Philippine delicacy. Consequently, the demand for native pigs has recently become more prominent, making it a practical source of income for pig producers with limited capital and are incapable of sustaining the expensive feeds used for commercial pigs (Manipol et al., 2014). In spite of this, several farmers are still hesitant to engage in native pig production because of their perception that it is not a profitable venture. This kind of perception towards native pig production is due to the fact that small-scale producers lack marketing knowledge about the potential buyers and the place where they could sell native pigs (Cabriga, 2016). Producers are also prompted not to grow native pigs because of the notion that native pig production is only profitable during peak seasons or festivals.

According to native pig producers, the price and the volume of native pigs being sold are high during the peak of demand but during the lean season, they are forced to drop the price, resulting in a high volume of unsold native pigs. In this case, the producers are compelled to use the unsold native pigs for personal or home consumption, while some are forced to sell their produce to neighbors on credit arrangement. This leads them to have little or no capital to use to finance their operations to meet the increasing demand for native pigs. Considering these scenarios, it is then imperative to have a clear understanding of the marketing practices of each participant in order to facilitate a smooth flow of information to native pig producers, traders, and consumers.

With a rising demand for organic products nowadays, the Philippine native pig meat is seen as a healthy alternative to commercial pig meat in the market and as a lucrative source of income for producers. These foreseeable economic value and potential of native pigs resulted in research and development programs from various government and non-government institutions. These institutions are working together to improve the native pig industry’s production and marketing aspects. The recent developments in native pig production resulted in genetically- improved native pigs having high uniformity in physical characteristics, an increase in litter size, and an increase in growth rate (DOST-PCAARRD, 2017).

The increasing popularity and demand for native pigs drive the need to increase production to cope with the demand of consumers and processors. However, despite the development of the country’s native pig industry, the goal of developing the native pig industry has not been achieved over time because several pig producers are still reluctant in producing native pigs.

In Sta. Maria, Bulacan, even though the municipality has a suitable topographic area and climatic condition for raising native pigs, native pig raisers are discouraged to increase their production because they are having difficulty in selling their produce. Moreover, according to the Municipal Agriculture Office (MAO) of Sta. Maria, Bulacan, the native pig growers in the municipality have decreased through the years due to land conversion, and due to the belief that commercial pig production is a more sustainable enterprise than native pig production. With pig raisers’ hesitancy in raising native pigs, the country is becoming more dependent on imported breeds in terms of local multiplication and production of commercial hybrids (Bondoc, Dominguez & Peñalba, 2013).

According to the Municipal Agriculture Office of Sta. Maria (2018), since the majority of these native pig raisers are small-scale producers and are dispersed in distant areas, directly transporting their produce to the market will be unprofitable and thus, some of these native pig producers are left with no choice but to sell their produce online. The native pigs produced by the farmers in distant farms pass several intermediaries such as village agents, hog dealers, and lechon processors before they reach households as target consumers. Losses and other marketing costs such as transportation costs, packaging costs, and storage costs are also incurred along the way, which are later translated to an unreasonably high selling price of the product for the consumers. Moreover, DOST-PCAARRD (2017) reported that the high demand for a consistent and stable supply of native pigs in the market is hardly met by the native pig producers. This unstable supply of native pigs in the country is reflected by the non-harmonious flow of information between producers and consumers. In this situation, vital information on the marketing of native pigs becomes essential.

Sta. Maria, Bulacan is a strategic area for native pig production however, the development of the native pig industry in the area is adversely affected by the asymmetry in information between producers and consumers. Given this, it is imperative to determine and analyze the different marketing practices of the native pig industry participants in Sta. Maria. A clear understanding of the marketing of native pigs can, in turn, help supply the growing demand for the product. To improve the effectiveness of information dissemination, there is also a need to determine what factors contribute to the asymmetry of information on the marketing of native pigs.

GEOGRAPHIC FLOW OF THE MARKETING NATIVE PIGS IN STA. MARIA, BULACAN

A complete list of native pig producers was obtained from the MAO of Sta. Maria, where simple random sampling was done to identify the respondents from the municipality’s major native pigs-producing barangays, Pulong Buhangin, Silangan, and Buenavista. These identified native pig producers served as the reference point in tracing the traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors. Moreover, purposive sampling was employed in selecting consumer-respondents. A total of 106 market participants were interviewed in this study, including 30 native pig raisers, 12 traders, 11 wholesaler-retailers, 11 retailers, 11 processors, and 30 consumers. The respondents can be found in four different locations namely: Sta. Maria (74 respondents), San Jose del Monte (13 respondents), and Norzagaray, Bulacan (7 respondents); and Fairview, Quezon City (12 respondents).

SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS

Socio-economic characteristics of native pig market participants

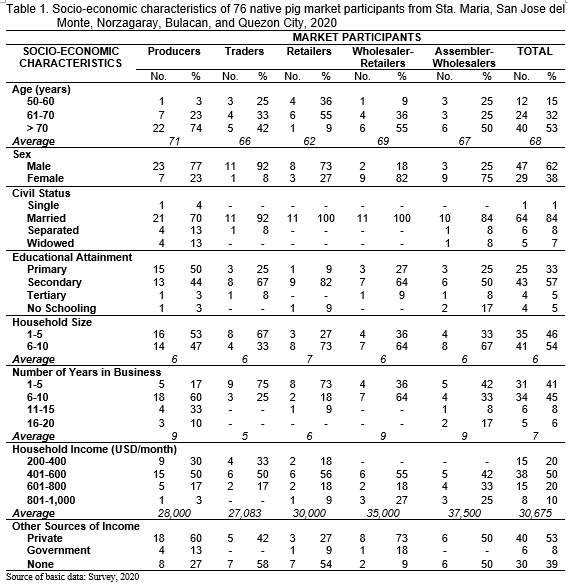

Based on the study, the mean age for the whole sample was 68-years old, with the youngest (minimum value) respondent at 50 years old while the oldest (maximum value) being 79-years old. Since the population of native pig raisers in the area is mostly from elderly groups, it is difficult for them to augment their operations because native pig raising requires intensive labor on the farm. The majority (77%) of the producer- respondents, majority of traders (92%), and retailers (73%) were comprised of male native pig raisers while the majority of native pig wholesaler-retailers (82%) and processors (75%) were comprised of females. Table 1 also shows that chain is mainly comprised of key participants that are married and have family members who can help them in raising and marketing native pigs.

Among the 76 respondents, only five percent (5%) were able to pursue tertiary education (college). Fifty-seven percent (57%) were able to reach and/or finish secondary education (high school), while 33% were only able to reach and/or finish primary education (elementary), and 5% did not go to school at all. It can also be observed that the native pig producers and market intermediaries still have relatively low work experience in the native pig enterprise. Based on the interviews, many of the respondents are originally involved in the production and marketing of the conventional white pigs but recently have been interested in raising and marketing native pigs as the demand in the market for native pig increases. Moreover, the majority of the key participants have 6-10 household size, half (50%) of the key participants have monthly household incomes ranging from US$400 to US$600 and 39% of the key participants have no other sources of income.

Socio-economic characteristics of native pig consumers

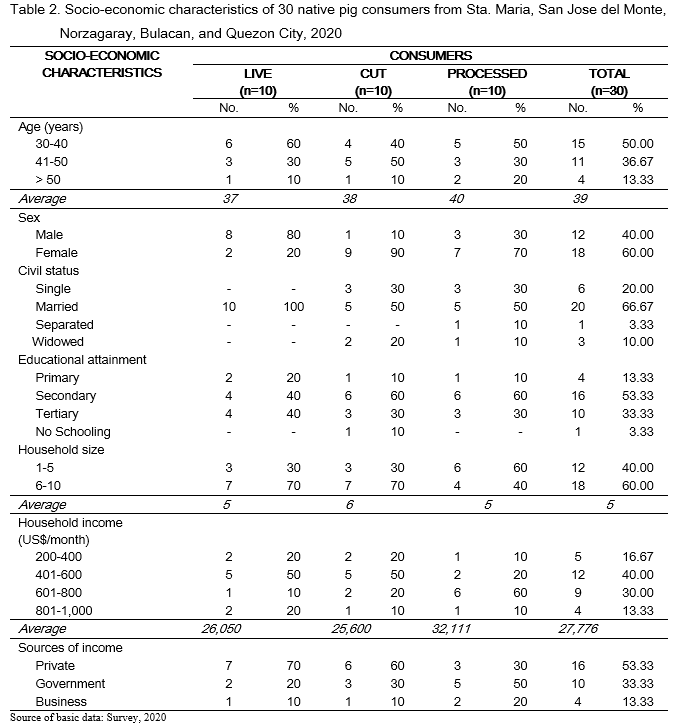

On the other hand, most (60%) of the live native pig consumers and half (50%) of processed native pig consumers were composed of individuals that are over the age of 30 to 40 years old. Meanwhile, 50% of the cut native pig consumer-respondents were composed of individuals that are over the age of 41 to 50 years old. The mean age for the whole sample was 39 years old, wherein the youngest respondent was 30 years old while the oldest was 54 years old. The majority (80%) of the live native pig consumers were comprised of male individuals who slaughter and cook the meat themselves. On the other hand, the majority of cut (90%) and processed (70%) native pig consumers were commonly comprised of females (Table 4). Most (60%) of the consumer respondents were comprised of females because they are usually the ones in-charge of food preparation. Hence, they are expected to be the ones who decide, buy, and make food for the household. Results also showed that most (67%) of the consumer-respondents were married. The average household size of the consumer-respondents was five, which shows that the chain has consumers who have households to feed (Table 2).

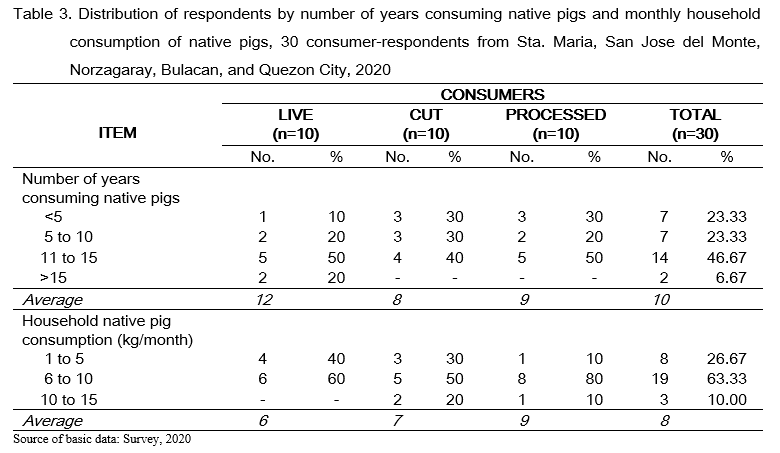

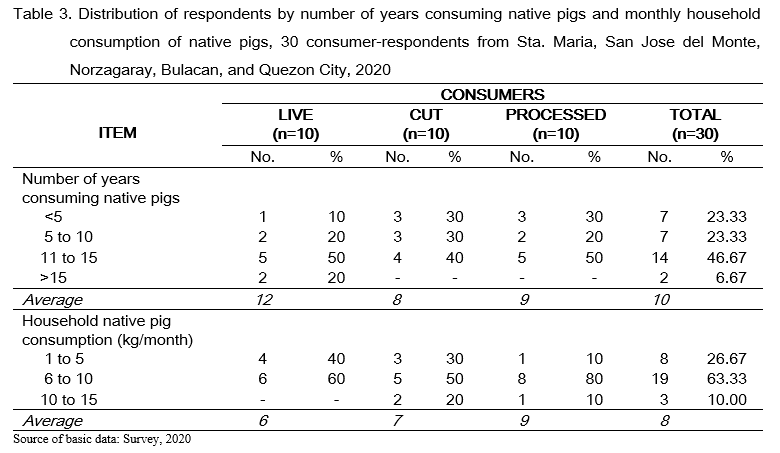

Meanwhile, Table 3 shows that 46.67% of the consumer-respondents have been consuming native pigs for 11 to 15 years, 23.33% each for less than 5 years, and 5 to 10 years, and 6.67% have been consuming native pigs for more than 15 years. Furthermore, the average monthly consumption of the households of respondents was approximately eight (8) kilograms per month.

MARKETING PRACTICES

The practices employed by the key players in the marketing of native pigs include handling, transporting, slaughtering/butchering, packaging, storing, and processing. Handling and packaging were performed by all the market participants while transporting was performed by the traders and wholesaler-retailers. Storing was done by wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors, while processing was only done by processors.

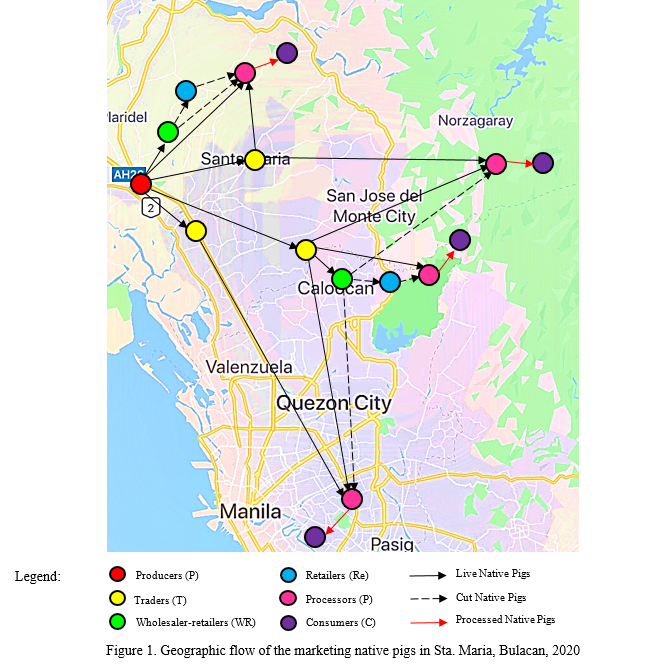

The product and geographic flows in the marketing of native pigs were identified using the forward tracing approach, from the native pig raisers to processors. The native pig raisers, who are located in Sta. Maria bought their material inputs from the input suppliers in Malolos and Meycauayan, Bulacan. Meanwhile, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and retailers can be found in Sta. Maria and San Jose del Monte, Bulacan. Lastly, processors are located in Sta. Maria, San Jose del Monte, and Norzagaray, Bulacan, as well as Fairview, Quezon City.

COSTS AND RETURNS

Using forward tracing approach from the native pig raisers to processors, there were eight identified marketing channels used in marketing native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan: (1) Ra→T→WR→Re→P; (2) Ra→T→WR→P; (3) Ra→T→Re→P; (4) Ra→T→P; (5) Ra→WR→Re→P; (6) Ra→WR→P; (7) Ra→Re→P; and (8) Ra→P, where “Ra” stands for native pig raisers, “T” for traders, “WR” for wholesaler-retailers, “Re” for retailers, and “P” for processors.

However, this study only tackled the two most common marketing channels used per season. The marketing channels considered for regular season were: (1) Ra→T→WR→P; (2) Ra→WR→Re→P, while for the lean season: (1) Ra→T→WR→Re→P; (2) Ra→T→WR →P, and for peak season: (1) Ra→WR→P; (2) Ra→P.

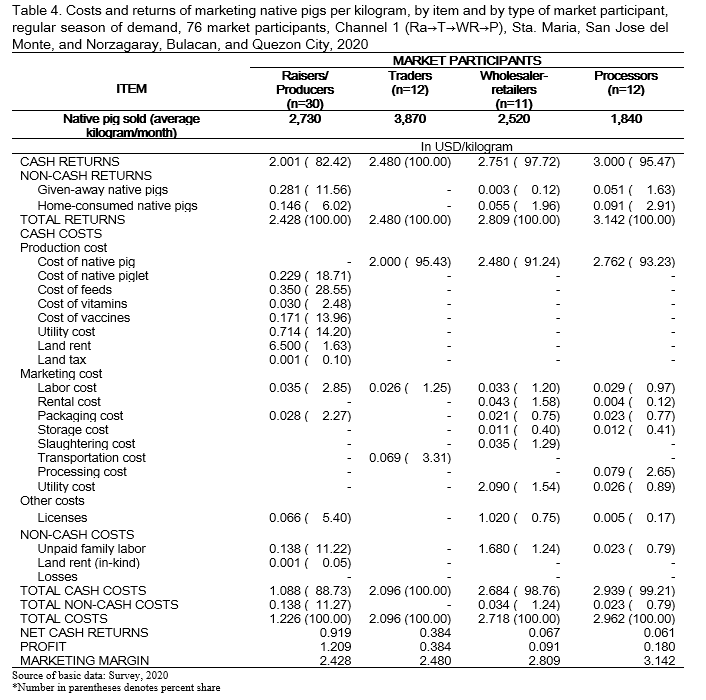

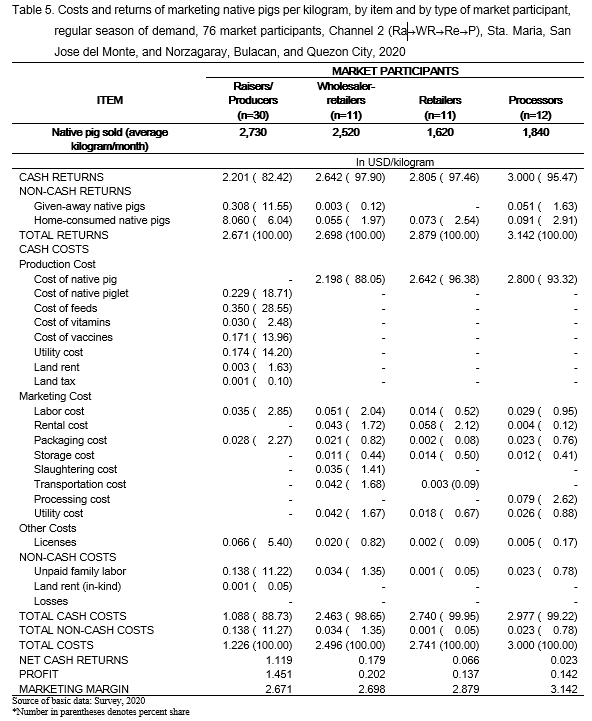

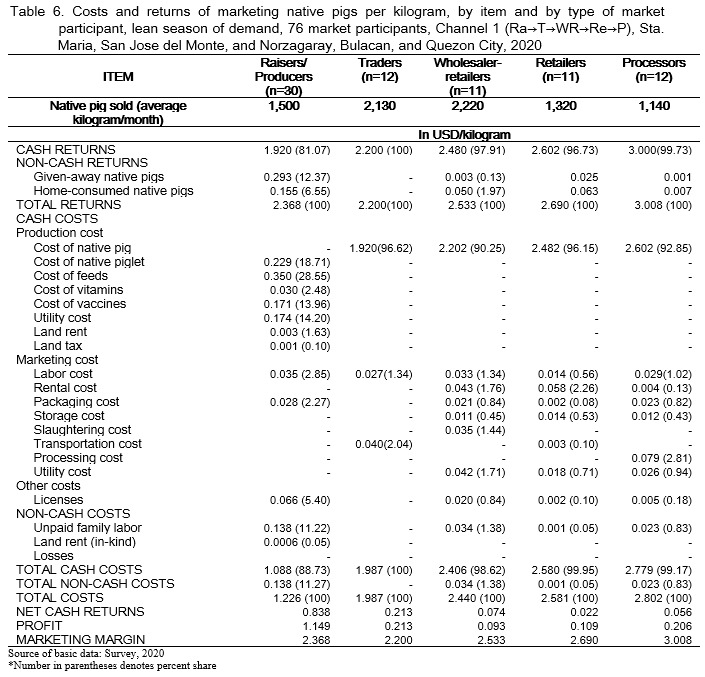

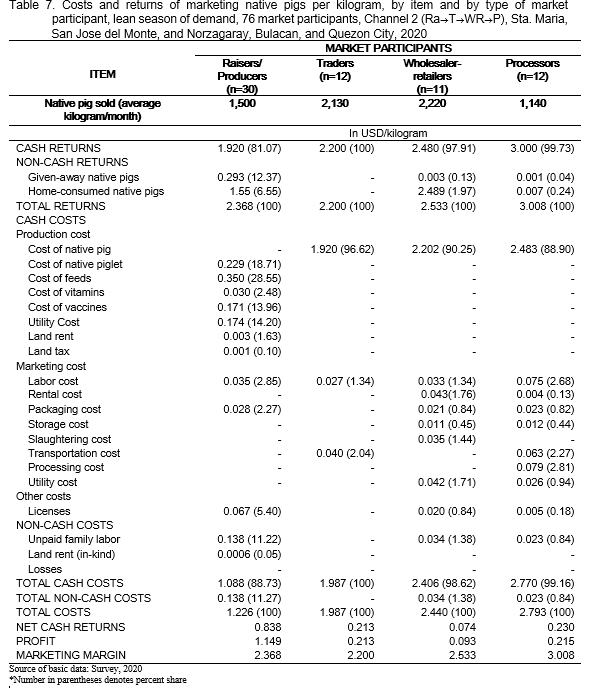

The costs and returns for the market participants of the native pig industry in Sta. Maria, Bulacan were computed to determine the profit gained by the participants per kilogram of native pigs. For native pig raisers, the profit was computed by getting the difference between the total returns and the total cost (production and marketing costs). For the traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors, the profit was computed by getting the difference between the total returns and the total marketing cost. In this study, both cash and non-cash costs were considered as part of production and marketing costs. The cash costs consisted of the production costs, transportation costs, handling costs, packaging costs, labor costs, rental costs, and other costs such as the cost of legal licenses. On the other hand, the non-cash costs included unpaid family labor, land rent (in-kind), given-away native pigs, and losses.

Costs and returns of marketing native pigs (regular season of demand)

The costs and returns in marketing channel 1 during regular season showed that the average profit from a kilogram of native pigs by the producers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and processors are US$1.21, US$0.38, US$0.09, and US$0.18, respectively. The costs and returns in marketing channel 2 during regular season showed that the average profit from a kilogram of native pigs by the producers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and processors are US$1.45, US$0.20, US$0.14, and US$0.14, respectively.

Costs and returns of marketing native pigs (lean season of demand)

During the lean season, the average profits earned by some marketing participants are relatively lower compared to their average profit during the regular season. The costs and returns in marketing channel 1 during lean season showed that the average profit from a kilogram of native pigs by the producers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors are US$ 1.15, US$ 0.21, US$ 0.09, US$ 0.11, and US$ 0.21, respectively. The costs and returns in marketing channel 2 during lean season showed that the market participant that gained the highest average profit was the native pig raisers at US$ 1.15 per kilogram. This is followed by processors, traders, and wholesaler-retailers at US$ 0.21, US$ 0.21, and US$ 0.09, respectively.

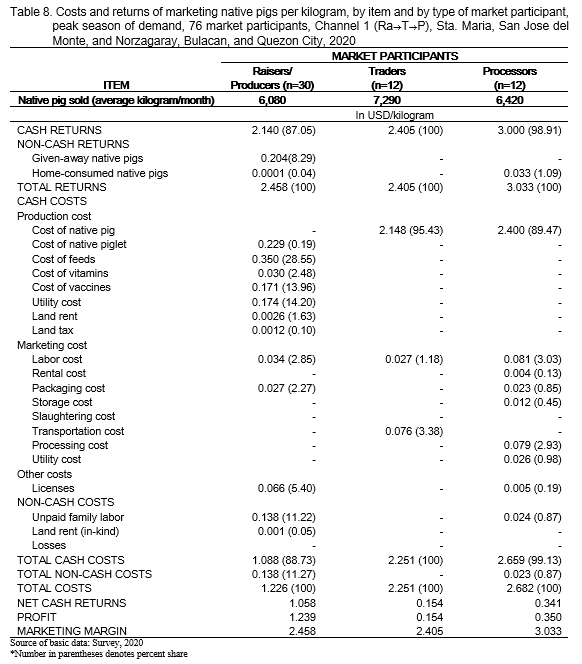

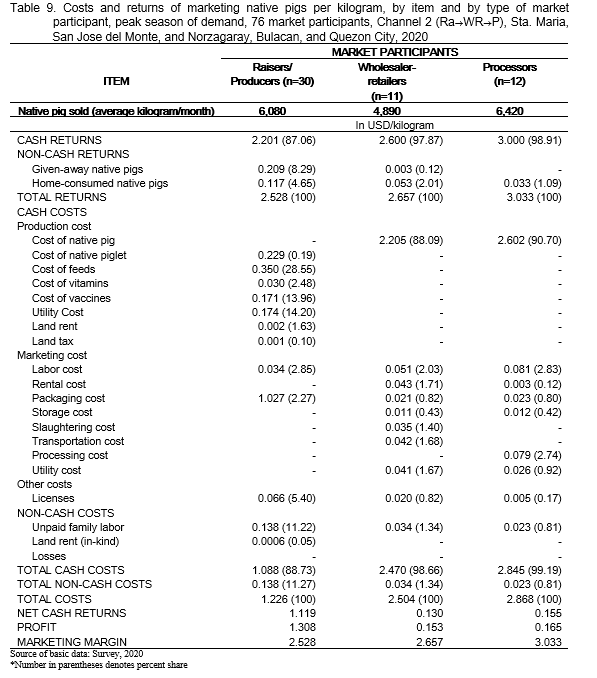

Costs and returns of marketing native pigs (peak season of demand)

During the peak season, the average profit earned by some marketing participants is relatively higher compared to their average profit during the regular season. The costs and returns in marketing channel 1 during peak season showed that the native pig raisers gained the highest average profit, at US$ 1.24 per kilogram, among the market participants. This is followed by processors, and traders at US$ 0.35 and US$ 0.15, respectively. The costs and returns in marketing channel 2 during peak season showed that average profit per kilogram of raisers, wholesaler-retailers, and processors are US$ 1.31, US$ 0.15, and US$ 0.16, respectively.

NATIVE PIG INDUSTRY SUPPLY-DEMAND GAP

The problems encountered by each marketing participants were also identified to understand the underlying causes in the supply-demand gap in the native pig industry. According to the native pig raisers, they have a problem with massive land conversion in Sta. Maria and a shortage of farm workers. Meanwhile, traders struggle from the economic repercussions of traffic jams and potholes in roads. Wholesaler-retailers, however, face problems in paying their rental costs and problems on the acquisition of the license. Likewise, retailers also encounter challenges in paying their rental costs for stalls in the market and securing native pig meat supply during peak season. Furthermore, problems in securing the supply of native pig ingredients have been the major concern for processors. They also face problems with the lack of information on standard pricing for native pigs.

To further determine the problems of the marketing participants, the Likert scale was also used in assessing the availability and accessibility of the logistics and support services provided to the market participants. Market participants were asked to rate the availability of credit, transportation, and support services from 1 (if it was very unavailable) to 5 (if it was very available). Moreover, they were asked to rate their answer for accessibility of the logistics and support services from 1 (if it was very inaccessible) to 5 (if it was very accessible). A high proportion of the market participants graded the availability and accessibility of credit and support services as very unavailable and very inaccessible. However, even though the availability and accessibility of transportation were rated as highly accessible and available, market participants stated that they are still not satisfied with the quality of the transportation provided to them, because of the substandard farm-to-market roads that negatively affects the quality of native pig meat.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In general, it was found that the production and marketing of native pigs has positive net returns for all of its marketing participants. However, the results show that the potential of the industry is not being maximized due to inadequate logistics and other support services provided for the marketing participants. Therefore, the following are recommended to improve the marketing of native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan:

Improvements in the marketing of native pigs

Results showed that the marketing of native pigs during lean and regular seasons will be more efficient if the processors would procure the native pig meat from the wholesaler-retailers and not from the retailers because of the expected lower marketing cost and the shorter marketing channel. Moreover, the marketing of native pigs during the peak season will be more efficient if the native lechon processors would procure the native pig meat from the traders and not from the native pig meat wholesaler-retailers. This is because lechon products are being roasted as a whole pig carcass, thus it does not require much of slaughtering and butchering activities performed by the wholesaler-retailers. On the other hand, the marketing of native pigs during the peak season will be more efficient for the native tocino and native chicharon processors if they would procure the native pig meat from the wholesaler-retailers and not from the traders. This is because tocino and chicharon products are being processed as cut native pig meats, thus require slaughtering and butchering activities performed by the wholesaler-retailers.

Formulation of a Comprehensive Land Use Plan

Since Sta. Maria is landlocked near Metro Manila, the municipality has been subjected to massive land conversions, wherein agricultural lands are being converted to commercial and residential areas. As a result, native pig raisers as well as other farmers, are facing the problem on expanding their farms and increasing their agricultural production. According to the Provincial Agriculture Office of Bulacan, this massive land conversion is also one of the reasons for the declining performance of the province in hog production. It is, therefore, recommended that the local government of Bulacan, together with the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) should work on formulating a comprehensive land use plan in Sta. Maria, Bulacan, specifically on the reclassification and conversion of agricultural lands. Protecting these land areas is essential in upholding agricultural viability and securing food production, especially since Bulacan is one of the main agricultural lands in the country.

Development of research and extension programs for native pig raising in Bulacan

Currently, native pig-related studies and programs of the government are solely focused in Region IV-A, which is not accessible for native pig raisers and market participants in Bulacan. According to the interviews, native pig raisers experienced losses on their initial years on native pig raising because of the lack of understanding and knowledge in native pig venture. Similar to the programs conducted in Region IV-A, an increase in farm productivity and efficiency is one of the main concerns of the native pig raisers in Sta. Maria. With this, the development of research and extension programs on native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan should also be prioritized by the Department of Agriculture (DA) and DOST-PCAARRD. These native pig-related seminars and projects will not only be beneficial to native pig raisers but can also help in promoting native pig raising to other hog raisers in Bulacan and nearby provinces.

REFERENCES

ASPILE, S., MANIPOL, N., DEPOSITARIO, D., & AQUINO, N. (2016). Profitability of swine enterprises by scale of operation and production system in two hog-producing towns in Bulacan, Philippines [Abstract]. Food Agriculture Organization of United Nations. Retrieved from http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=PH2017000484.

BAGUIO, S. S. (2017, July 03). R&D Activities to Improve Native Pig Production. Retrieved October 13, 2018, from http://www.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/home/portal/index.php/quick-information-d....

BARROGA, A. (2014). A Dynamic Philippine Swine Industry: Key to Meeting Challenges and Technological Innovations. Central Luzon State University. Retrieved October 16, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309549555_A_DYNAMIC_PHILIPPINE_SWINE_INDUSTRY_KEY_TO_MEETING_CHALLENGES_AND_TECHNOLOGICAL_INNOVATIONS.

BRION, A. B. (2018, January 25). Raising Native Animals. Business Diary Philippines. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://businessdiary.com.ph/6301/raising-native-animals/.

FAO–UNESCO (2002). Education for Rural Development in Asia: Experiences and Policy Lessons. Bangkok, Thailand. http://www.fao.org/sd/2002/KN1201en. htm.

GEROMO FB (1993). Survey and evaluation of indigenous pig production and management practices in the Zamboanga Peninsula [Philippines].

GUERRERO, R. D., III. (2016, February 1). Agriculture: 2016-02-01-Currents. PressReader. Retrieved October 29, 2018, from https://www.pressreader.com/philippines/agriculture/2016 0201/282458527993394.

GUERRERO, R. D., III. (2018, July 29). Raising Native Pigs is Profitable and Environmentally Friendly. Retrieved October 23, 2018, from http://agriculture.com.ph/2018/07/29/raising-native-pigs-is-profitable-a....

GURU, F. (2016, October 3). Philippine Natives: Wealth & Treasures Transforming Lives. Alternative Journalism.

ISSUES ON PHILIPPINE NATIVE ANIMALS TACKLED. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2018, from http://www.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/home/portal/index.php/quick-informationdi... issues-on-philippine-native-animalstackled?fbclid=IwAR2Q5lrHF6kpcpURv41YfggiA1jjPaN9DPqpGB2_nhvHc4-qM0GEfUFUklU.

HOBBYIST TURN NATIVE PIG FARMING SUCCESS INTO BUSINESS. (2018, April18). AgriMag. Retrieved October 28, 2018, from http://agriculture.com.ph/201 8/04/18/hobbyist-turns-pig-farming-success-into-business.

KOHL, R., & UHL, J. (2005). Analysis of Marketing Function, Marketing Efficiency and Spatial Co-Integration of Rohu (Labeo rohita) Fish in Some Selected Areas of Bangladesh. European Journal of Business and Management. Retrieved October 02, 2018, from http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/119374/15/15_chapter 6.pdf.

LEE, S. (2016). Utilization of native animals for building rural enterprise in warm climate zone [Abstract]. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center. Retrieved November 17, 2018, from http://www.fftc.agnet.org/library.php?func=view&id=20120103110958.

LOGMAO, J. A. (2019). Marketing of Tilapia in Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro, 2019 (Unpublished thesis). College of Economics and Management, University of the Philippines Los Baños Laguna.

MADDUL, S. B. (1991). Production management and characteristics of native pigs in the Cordillera (Master's thesis, University of the Philippines Los Baños). Food and Agriculture of the United Nations.

MANIPOL, N. P., FLORES, M., TAN, R., AQUINO, N., & BATICADOS, G. (2014). Value Chain Analysis of Philippine Native Swine (Sus Scrofa Philippinensis) Processed as Lechon in Major Production Areas in the Philippines. Journal of Global Business and Trade, 10, 77-91. Retrieved October 2, 2018, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_id=2999245.

MASON, I.L. 1996. A World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types and Varieties. Fourth Edition.C.A.B International. 273 pp.

MONLEON AM (2011). Local Conservation Efforts for the Philippine Native Pig (Sus domesticus) in Marinduque. Philippine Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences. 32(1).

MUNICIPALITY OF SANTA MARIA. (2007). Retrieved October 8, 2018, from https://www.bulacan.gov.ph/santamaria/index.php.

NATIVE PIG PRODUCTION. (n.d.). Retrieved October 03, 2018, from http://www.nzdl.org/gsdlmod?e= d-00000-00---off-0hdl--00-0----0-10-0---0---0direct-10---4-------0-1l--11-en-50---20 about --- 00-0-1-00-0--4----0-0-11-10-0utfZz 00&cl=CL1.10&d=H ASH01e4aed98f2087737 04 e3548.11>=1.

NORONHA, A. C. (2017, December). Productivity of Native Pigs in Subsistence Farming and Their Roles in Community Development in Timor-Leste. Retrieved October 02, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321409814_Productivity_of_Nativ....

OH, J. (2014). Genetic Analysis of Philippine Native Pigs (Sus scrofa L.) Using Microsatellite Loci [Abstract]. Philippine Journal of Science,143(1), 87-94. Retrieved November 23, 2018, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4c26/ffe732e243c134028fa249794cc63a79ed....

SLAVIN, J. (2012). Health Benefits of Fruits and Vegetables [Abstract]. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 4. doi:10.3945/an.112.002154.

THE DIFFERENT BREEDS OF SWINE. (n.d.). Retrieved September 15, 2018, from http://www.thepigsite.com/ focus/advertiser/4499/the-different-breeds-of-swine-philippine-native philippine- native-pig-breed-philippine-native-gilts-sows-and-boars.

THE POTENTIAL IN RAISING NATIVE PIGS. (2016, September 1). PressReader. Retrieved October 8, 2018, from https://www.pressreader.com/philippines/agriculture/20160901/28222660016....

VILLANUEVA, J. J. O., & SULABO, R. C. (2018). Production, Feeding and Marketing Practices of Native Pig Raisers in Selected Regions of the Philippines. Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 7(12), 383–392.

YAP, J. (2017, November 21). NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE PHILIPPINE SWINE INDUSTRY. Retrieved September 19, 2018, from http://agriculture.com.ph/2017/11/21/new-opportunities-for-the-philippin....

Marketing of Native Pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan, 2020

ABSTRACT

Philippine native pig meat is seen as a healthy alternative to commercial pig meat in the market and as a lucrative source of income for producers. However, despite the development of the country’s native industry, the goal of developing the native pig industry has not been achieved over time because several pig producers are still reluctant in producing native pigs. This study identified the marketing participants of native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan; described the marketing practices and strategies employed by the native pig raisers and intermediaries; determined the product and geographic flows of native pigs; and analyzed the cost and returns in marketing native pigs. A total of 106 market participants were interviewed in this study, including 30 native pig raisers, 12 traders, 11 wholesaler-retailers, 11 retailers, 11 processors, and 30 consumers. There were eight identified marketing channels in marketing native pigs in Sta. Maria but this study only discussed the two most common marketing channels used per season. Based on the study, the native pig raisers in Sta. Maria bought their material inputs from Malolos and Meycauayan. Meanwhile, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and retailers can be found in Sta. Maria and San Jose del Monte, and processors in Sta. Maria, San Jose del Monte, and Norzagaray, and Fairview, Quezon City. The practices employed by these key players include handling, transporting, slaughtering/butchering, packaging, storing, and processing. Results also showed that the average profit of native pig raisers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors differ depending on the season and marketing channel used.

Keywords: native, pigs, marketing, season

INTRODUCTION

Pigs, scientifically known as Sus scrofa domesticus, is the major source of protein to Filipinos, as it provides about 60% of the total animal meat consumption of Filipinos (Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development [DOST-PCAARRD], 2016). In 2017, the Philippine pig industry has contributed significantly to the world’s pig production; it ranked as the third top-pig producer in Asia, and eighth in the world. It is also the second-largest contributor to the total value of agricultural production in the country, contributing 18.28%, with a gross value of US$3.80 billion at current prices. The progress in the country’s pig industry is also notable since the hog inventory of the country went up to 12.71 million heads in 2018. This is a 0.83% increase in the country’s pig production as compared to 12.6 million pig production in 2017 (Philippine Statistics Authority [PSA], 2019). Moreover, according to the PSA, the country’s pig industry is dominated by backyard producers, which constitutes approximately 65% of the total production. Among the major hog-producing provinces in the Philippines, Cebu had the highest number of slaughtered hogs in 2018 with 908,114 heads slaughtered, followed by the province of Rizal (755,733), Pampanga (681,238) and Bulacan (673,397).

In 2011, Sta. Maria is classified as one of the top hog-producing municipalities in Bulacan (Bulacan Provincial Agriculture Office, 2012, as cited by Aspile et al., 2016). Sta. Maria has a generally warm climatic condition with average annual temperatures suitable for pig production (Aspile et al., 2016). It has also a relatively short distance away from market centers in the Philippines like Divisoria, which is just 35 kilometers away, and Pioneer Street Market, which is just 42 kilometers away. Because of these, Sta. Maria is deemed to have great potential in the expansion of backyard hog raising and native pig production.

One of the common breeds of pigs raised in backyard farms is the Philippine native pigs (Sus scrofa philippinensis). It is a small black pig with straight to low-set back and short legs and has a long snout and small, and erect ears (Manipol et al., 2014). This breed can be classified into two varieties called Ilocos and Jalajala, which are used in the development of other breeds such as Berkjala, Diani, Kaman, Koronadel, and Libtong. At present, it has four recognized species that may have evolved with the environment of the Philippine archipelago- Philippine warty pigs, Visayan warty pigs, Mindoro warty pigs, and Palawan bearded pigs (Mason, 1996).

Since Philippine native pigs are well-adapted to the country’s environmental condition, they do not require expensive housing and care, which makes them easier and cheaper to raise than commercial breeds (Guerrero III, 2016). Similarly, the Bureau of Animal Industry (2010) stated that raising a native pig incurs lower maintenance cost as it thrives well on locally-available feeds, and can be raised without the use of chemical inputs. Moreover, the native pig is also known to have good mothering ability and to be very prolific in terms of production (Mason, 1996).

Given its leaner and tastier meat and crispier roasted skin, native pigs are also being processed into lechon, a traditional Philippine delicacy. Consequently, the demand for native pigs has recently become more prominent, making it a practical source of income for pig producers with limited capital and are incapable of sustaining the expensive feeds used for commercial pigs (Manipol et al., 2014). In spite of this, several farmers are still hesitant to engage in native pig production because of their perception that it is not a profitable venture. This kind of perception towards native pig production is due to the fact that small-scale producers lack marketing knowledge about the potential buyers and the place where they could sell native pigs (Cabriga, 2016). Producers are also prompted not to grow native pigs because of the notion that native pig production is only profitable during peak seasons or festivals.

According to native pig producers, the price and the volume of native pigs being sold are high during the peak of demand but during the lean season, they are forced to drop the price, resulting in a high volume of unsold native pigs. In this case, the producers are compelled to use the unsold native pigs for personal or home consumption, while some are forced to sell their produce to neighbors on credit arrangement. This leads them to have little or no capital to use to finance their operations to meet the increasing demand for native pigs. Considering these scenarios, it is then imperative to have a clear understanding of the marketing practices of each participant in order to facilitate a smooth flow of information to native pig producers, traders, and consumers.

With a rising demand for organic products nowadays, the Philippine native pig meat is seen as a healthy alternative to commercial pig meat in the market and as a lucrative source of income for producers. These foreseeable economic value and potential of native pigs resulted in research and development programs from various government and non-government institutions. These institutions are working together to improve the native pig industry’s production and marketing aspects. The recent developments in native pig production resulted in genetically- improved native pigs having high uniformity in physical characteristics, an increase in litter size, and an increase in growth rate (DOST-PCAARRD, 2017).

The increasing popularity and demand for native pigs drive the need to increase production to cope with the demand of consumers and processors. However, despite the development of the country’s native pig industry, the goal of developing the native pig industry has not been achieved over time because several pig producers are still reluctant in producing native pigs.

In Sta. Maria, Bulacan, even though the municipality has a suitable topographic area and climatic condition for raising native pigs, native pig raisers are discouraged to increase their production because they are having difficulty in selling their produce. Moreover, according to the Municipal Agriculture Office (MAO) of Sta. Maria, Bulacan, the native pig growers in the municipality have decreased through the years due to land conversion, and due to the belief that commercial pig production is a more sustainable enterprise than native pig production. With pig raisers’ hesitancy in raising native pigs, the country is becoming more dependent on imported breeds in terms of local multiplication and production of commercial hybrids (Bondoc, Dominguez & Peñalba, 2013).

According to the Municipal Agriculture Office of Sta. Maria (2018), since the majority of these native pig raisers are small-scale producers and are dispersed in distant areas, directly transporting their produce to the market will be unprofitable and thus, some of these native pig producers are left with no choice but to sell their produce online. The native pigs produced by the farmers in distant farms pass several intermediaries such as village agents, hog dealers, and lechon processors before they reach households as target consumers. Losses and other marketing costs such as transportation costs, packaging costs, and storage costs are also incurred along the way, which are later translated to an unreasonably high selling price of the product for the consumers. Moreover, DOST-PCAARRD (2017) reported that the high demand for a consistent and stable supply of native pigs in the market is hardly met by the native pig producers. This unstable supply of native pigs in the country is reflected by the non-harmonious flow of information between producers and consumers. In this situation, vital information on the marketing of native pigs becomes essential.

Sta. Maria, Bulacan is a strategic area for native pig production however, the development of the native pig industry in the area is adversely affected by the asymmetry in information between producers and consumers. Given this, it is imperative to determine and analyze the different marketing practices of the native pig industry participants in Sta. Maria. A clear understanding of the marketing of native pigs can, in turn, help supply the growing demand for the product. To improve the effectiveness of information dissemination, there is also a need to determine what factors contribute to the asymmetry of information on the marketing of native pigs.

GEOGRAPHIC FLOW OF THE MARKETING NATIVE PIGS IN STA. MARIA, BULACAN

A complete list of native pig producers was obtained from the MAO of Sta. Maria, where simple random sampling was done to identify the respondents from the municipality’s major native pigs-producing barangays, Pulong Buhangin, Silangan, and Buenavista. These identified native pig producers served as the reference point in tracing the traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors. Moreover, purposive sampling was employed in selecting consumer-respondents. A total of 106 market participants were interviewed in this study, including 30 native pig raisers, 12 traders, 11 wholesaler-retailers, 11 retailers, 11 processors, and 30 consumers. The respondents can be found in four different locations namely: Sta. Maria (74 respondents), San Jose del Monte (13 respondents), and Norzagaray, Bulacan (7 respondents); and Fairview, Quezon City (12 respondents).

SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS

Socio-economic characteristics of native pig market participants

Based on the study, the mean age for the whole sample was 68-years old, with the youngest (minimum value) respondent at 50 years old while the oldest (maximum value) being 79-years old. Since the population of native pig raisers in the area is mostly from elderly groups, it is difficult for them to augment their operations because native pig raising requires intensive labor on the farm. The majority (77%) of the producer- respondents, majority of traders (92%), and retailers (73%) were comprised of male native pig raisers while the majority of native pig wholesaler-retailers (82%) and processors (75%) were comprised of females. Table 1 also shows that chain is mainly comprised of key participants that are married and have family members who can help them in raising and marketing native pigs.

Among the 76 respondents, only five percent (5%) were able to pursue tertiary education (college). Fifty-seven percent (57%) were able to reach and/or finish secondary education (high school), while 33% were only able to reach and/or finish primary education (elementary), and 5% did not go to school at all. It can also be observed that the native pig producers and market intermediaries still have relatively low work experience in the native pig enterprise. Based on the interviews, many of the respondents are originally involved in the production and marketing of the conventional white pigs but recently have been interested in raising and marketing native pigs as the demand in the market for native pig increases. Moreover, the majority of the key participants have 6-10 household size, half (50%) of the key participants have monthly household incomes ranging from US$400 to US$600 and 39% of the key participants have no other sources of income.

Socio-economic characteristics of native pig consumers

On the other hand, most (60%) of the live native pig consumers and half (50%) of processed native pig consumers were composed of individuals that are over the age of 30 to 40 years old. Meanwhile, 50% of the cut native pig consumer-respondents were composed of individuals that are over the age of 41 to 50 years old. The mean age for the whole sample was 39 years old, wherein the youngest respondent was 30 years old while the oldest was 54 years old. The majority (80%) of the live native pig consumers were comprised of male individuals who slaughter and cook the meat themselves. On the other hand, the majority of cut (90%) and processed (70%) native pig consumers were commonly comprised of females (Table 4). Most (60%) of the consumer respondents were comprised of females because they are usually the ones in-charge of food preparation. Hence, they are expected to be the ones who decide, buy, and make food for the household. Results also showed that most (67%) of the consumer-respondents were married. The average household size of the consumer-respondents was five, which shows that the chain has consumers who have households to feed (Table 2).

Meanwhile, Table 3 shows that 46.67% of the consumer-respondents have been consuming native pigs for 11 to 15 years, 23.33% each for less than 5 years, and 5 to 10 years, and 6.67% have been consuming native pigs for more than 15 years. Furthermore, the average monthly consumption of the households of respondents was approximately eight (8) kilograms per month.

MARKETING PRACTICES

The practices employed by the key players in the marketing of native pigs include handling, transporting, slaughtering/butchering, packaging, storing, and processing. Handling and packaging were performed by all the market participants while transporting was performed by the traders and wholesaler-retailers. Storing was done by wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors, while processing was only done by processors.

The product and geographic flows in the marketing of native pigs were identified using the forward tracing approach, from the native pig raisers to processors. The native pig raisers, who are located in Sta. Maria bought their material inputs from the input suppliers in Malolos and Meycauayan, Bulacan. Meanwhile, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and retailers can be found in Sta. Maria and San Jose del Monte, Bulacan. Lastly, processors are located in Sta. Maria, San Jose del Monte, and Norzagaray, Bulacan, as well as Fairview, Quezon City.

COSTS AND RETURNS

Using forward tracing approach from the native pig raisers to processors, there were eight identified marketing channels used in marketing native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan: (1) Ra→T→WR→Re→P; (2) Ra→T→WR→P; (3) Ra→T→Re→P; (4) Ra→T→P; (5) Ra→WR→Re→P; (6) Ra→WR→P; (7) Ra→Re→P; and (8) Ra→P, where “Ra” stands for native pig raisers, “T” for traders, “WR” for wholesaler-retailers, “Re” for retailers, and “P” for processors.

However, this study only tackled the two most common marketing channels used per season. The marketing channels considered for regular season were: (1) Ra→T→WR→P; (2) Ra→WR→Re→P, while for the lean season: (1) Ra→T→WR→Re→P; (2) Ra→T→WR →P, and for peak season: (1) Ra→WR→P; (2) Ra→P.

The costs and returns for the market participants of the native pig industry in Sta. Maria, Bulacan were computed to determine the profit gained by the participants per kilogram of native pigs. For native pig raisers, the profit was computed by getting the difference between the total returns and the total cost (production and marketing costs). For the traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors, the profit was computed by getting the difference between the total returns and the total marketing cost. In this study, both cash and non-cash costs were considered as part of production and marketing costs. The cash costs consisted of the production costs, transportation costs, handling costs, packaging costs, labor costs, rental costs, and other costs such as the cost of legal licenses. On the other hand, the non-cash costs included unpaid family labor, land rent (in-kind), given-away native pigs, and losses.

Costs and returns of marketing native pigs (regular season of demand)

The costs and returns in marketing channel 1 during regular season showed that the average profit from a kilogram of native pigs by the producers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and processors are US$1.21, US$0.38, US$0.09, and US$0.18, respectively. The costs and returns in marketing channel 2 during regular season showed that the average profit from a kilogram of native pigs by the producers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, and processors are US$1.45, US$0.20, US$0.14, and US$0.14, respectively.

Costs and returns of marketing native pigs (lean season of demand)

During the lean season, the average profits earned by some marketing participants are relatively lower compared to their average profit during the regular season. The costs and returns in marketing channel 1 during lean season showed that the average profit from a kilogram of native pigs by the producers, traders, wholesaler-retailers, retailers, and processors are US$ 1.15, US$ 0.21, US$ 0.09, US$ 0.11, and US$ 0.21, respectively. The costs and returns in marketing channel 2 during lean season showed that the market participant that gained the highest average profit was the native pig raisers at US$ 1.15 per kilogram. This is followed by processors, traders, and wholesaler-retailers at US$ 0.21, US$ 0.21, and US$ 0.09, respectively.

Costs and returns of marketing native pigs (peak season of demand)

During the peak season, the average profit earned by some marketing participants is relatively higher compared to their average profit during the regular season. The costs and returns in marketing channel 1 during peak season showed that the native pig raisers gained the highest average profit, at US$ 1.24 per kilogram, among the market participants. This is followed by processors, and traders at US$ 0.35 and US$ 0.15, respectively. The costs and returns in marketing channel 2 during peak season showed that average profit per kilogram of raisers, wholesaler-retailers, and processors are US$ 1.31, US$ 0.15, and US$ 0.16, respectively.

NATIVE PIG INDUSTRY SUPPLY-DEMAND GAP

The problems encountered by each marketing participants were also identified to understand the underlying causes in the supply-demand gap in the native pig industry. According to the native pig raisers, they have a problem with massive land conversion in Sta. Maria and a shortage of farm workers. Meanwhile, traders struggle from the economic repercussions of traffic jams and potholes in roads. Wholesaler-retailers, however, face problems in paying their rental costs and problems on the acquisition of the license. Likewise, retailers also encounter challenges in paying their rental costs for stalls in the market and securing native pig meat supply during peak season. Furthermore, problems in securing the supply of native pig ingredients have been the major concern for processors. They also face problems with the lack of information on standard pricing for native pigs.

To further determine the problems of the marketing participants, the Likert scale was also used in assessing the availability and accessibility of the logistics and support services provided to the market participants. Market participants were asked to rate the availability of credit, transportation, and support services from 1 (if it was very unavailable) to 5 (if it was very available). Moreover, they were asked to rate their answer for accessibility of the logistics and support services from 1 (if it was very inaccessible) to 5 (if it was very accessible). A high proportion of the market participants graded the availability and accessibility of credit and support services as very unavailable and very inaccessible. However, even though the availability and accessibility of transportation were rated as highly accessible and available, market participants stated that they are still not satisfied with the quality of the transportation provided to them, because of the substandard farm-to-market roads that negatively affects the quality of native pig meat.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In general, it was found that the production and marketing of native pigs has positive net returns for all of its marketing participants. However, the results show that the potential of the industry is not being maximized due to inadequate logistics and other support services provided for the marketing participants. Therefore, the following are recommended to improve the marketing of native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan:

Improvements in the marketing of native pigs

Results showed that the marketing of native pigs during lean and regular seasons will be more efficient if the processors would procure the native pig meat from the wholesaler-retailers and not from the retailers because of the expected lower marketing cost and the shorter marketing channel. Moreover, the marketing of native pigs during the peak season will be more efficient if the native lechon processors would procure the native pig meat from the traders and not from the native pig meat wholesaler-retailers. This is because lechon products are being roasted as a whole pig carcass, thus it does not require much of slaughtering and butchering activities performed by the wholesaler-retailers. On the other hand, the marketing of native pigs during the peak season will be more efficient for the native tocino and native chicharon processors if they would procure the native pig meat from the wholesaler-retailers and not from the traders. This is because tocino and chicharon products are being processed as cut native pig meats, thus require slaughtering and butchering activities performed by the wholesaler-retailers.

Formulation of a Comprehensive Land Use Plan

Since Sta. Maria is landlocked near Metro Manila, the municipality has been subjected to massive land conversions, wherein agricultural lands are being converted to commercial and residential areas. As a result, native pig raisers as well as other farmers, are facing the problem on expanding their farms and increasing their agricultural production. According to the Provincial Agriculture Office of Bulacan, this massive land conversion is also one of the reasons for the declining performance of the province in hog production. It is, therefore, recommended that the local government of Bulacan, together with the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) should work on formulating a comprehensive land use plan in Sta. Maria, Bulacan, specifically on the reclassification and conversion of agricultural lands. Protecting these land areas is essential in upholding agricultural viability and securing food production, especially since Bulacan is one of the main agricultural lands in the country.

Development of research and extension programs for native pig raising in Bulacan

Currently, native pig-related studies and programs of the government are solely focused in Region IV-A, which is not accessible for native pig raisers and market participants in Bulacan. According to the interviews, native pig raisers experienced losses on their initial years on native pig raising because of the lack of understanding and knowledge in native pig venture. Similar to the programs conducted in Region IV-A, an increase in farm productivity and efficiency is one of the main concerns of the native pig raisers in Sta. Maria. With this, the development of research and extension programs on native pigs in Sta. Maria, Bulacan should also be prioritized by the Department of Agriculture (DA) and DOST-PCAARRD. These native pig-related seminars and projects will not only be beneficial to native pig raisers but can also help in promoting native pig raising to other hog raisers in Bulacan and nearby provinces.

REFERENCES

ASPILE, S., MANIPOL, N., DEPOSITARIO, D., & AQUINO, N. (2016). Profitability of swine enterprises by scale of operation and production system in two hog-producing towns in Bulacan, Philippines [Abstract]. Food Agriculture Organization of United Nations. Retrieved from http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=PH2017000484.

BAGUIO, S. S. (2017, July 03). R&D Activities to Improve Native Pig Production. Retrieved October 13, 2018, from http://www.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/home/portal/index.php/quick-information-d....

BARROGA, A. (2014). A Dynamic Philippine Swine Industry: Key to Meeting Challenges and Technological Innovations. Central Luzon State University. Retrieved October 16, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309549555_A_DYNAMIC_PHILIPPINE_SWINE_INDUSTRY_KEY_TO_MEETING_CHALLENGES_AND_TECHNOLOGICAL_INNOVATIONS.

BRION, A. B. (2018, January 25). Raising Native Animals. Business Diary Philippines. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://businessdiary.com.ph/6301/raising-native-animals/.

FAO–UNESCO (2002). Education for Rural Development in Asia: Experiences and Policy Lessons. Bangkok, Thailand. http://www.fao.org/sd/2002/KN1201en. htm.

GEROMO FB (1993). Survey and evaluation of indigenous pig production and management practices in the Zamboanga Peninsula [Philippines].

GUERRERO, R. D., III. (2016, February 1). Agriculture: 2016-02-01-Currents. PressReader. Retrieved October 29, 2018, from https://www.pressreader.com/philippines/agriculture/2016 0201/282458527993394.

GUERRERO, R. D., III. (2018, July 29). Raising Native Pigs is Profitable and Environmentally Friendly. Retrieved October 23, 2018, from http://agriculture.com.ph/2018/07/29/raising-native-pigs-is-profitable-a....

GURU, F. (2016, October 3). Philippine Natives: Wealth & Treasures Transforming Lives. Alternative Journalism.

ISSUES ON PHILIPPINE NATIVE ANIMALS TACKLED. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2018, from http://www.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/home/portal/index.php/quick-informationdi... issues-on-philippine-native-animalstackled?fbclid=IwAR2Q5lrHF6kpcpURv41YfggiA1jjPaN9DPqpGB2_nhvHc4-qM0GEfUFUklU.

HOBBYIST TURN NATIVE PIG FARMING SUCCESS INTO BUSINESS. (2018, April18). AgriMag. Retrieved October 28, 2018, from http://agriculture.com.ph/201 8/04/18/hobbyist-turns-pig-farming-success-into-business.

KOHL, R., & UHL, J. (2005). Analysis of Marketing Function, Marketing Efficiency and Spatial Co-Integration of Rohu (Labeo rohita) Fish in Some Selected Areas of Bangladesh. European Journal of Business and Management. Retrieved October 02, 2018, from http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/119374/15/15_chapter 6.pdf.

LEE, S. (2016). Utilization of native animals for building rural enterprise in warm climate zone [Abstract]. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center. Retrieved November 17, 2018, from http://www.fftc.agnet.org/library.php?func=view&id=20120103110958.

LOGMAO, J. A. (2019). Marketing of Tilapia in Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro, 2019 (Unpublished thesis). College of Economics and Management, University of the Philippines Los Baños Laguna.

MADDUL, S. B. (1991). Production management and characteristics of native pigs in the Cordillera (Master's thesis, University of the Philippines Los Baños). Food and Agriculture of the United Nations.

MANIPOL, N. P., FLORES, M., TAN, R., AQUINO, N., & BATICADOS, G. (2014). Value Chain Analysis of Philippine Native Swine (Sus Scrofa Philippinensis) Processed as Lechon in Major Production Areas in the Philippines. Journal of Global Business and Trade, 10, 77-91. Retrieved October 2, 2018, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_id=2999245.

MASON, I.L. 1996. A World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types and Varieties. Fourth Edition.C.A.B International. 273 pp.

MONLEON AM (2011). Local Conservation Efforts for the Philippine Native Pig (Sus domesticus) in Marinduque. Philippine Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences. 32(1).

MUNICIPALITY OF SANTA MARIA. (2007). Retrieved October 8, 2018, from https://www.bulacan.gov.ph/santamaria/index.php.

NATIVE PIG PRODUCTION. (n.d.). Retrieved October 03, 2018, from http://www.nzdl.org/gsdlmod?e= d-00000-00---off-0hdl--00-0----0-10-0---0---0direct-10---4-------0-1l--11-en-50---20 about --- 00-0-1-00-0--4----0-0-11-10-0utfZz 00&cl=CL1.10&d=H ASH01e4aed98f2087737 04 e3548.11>=1.

NORONHA, A. C. (2017, December). Productivity of Native Pigs in Subsistence Farming and Their Roles in Community Development in Timor-Leste. Retrieved October 02, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321409814_Productivity_of_Nativ....

OH, J. (2014). Genetic Analysis of Philippine Native Pigs (Sus scrofa L.) Using Microsatellite Loci [Abstract]. Philippine Journal of Science,143(1), 87-94. Retrieved November 23, 2018, from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4c26/ffe732e243c134028fa249794cc63a79ed....

SLAVIN, J. (2012). Health Benefits of Fruits and Vegetables [Abstract]. National Center for Biotechnology Information, 4. doi:10.3945/an.112.002154.

THE DIFFERENT BREEDS OF SWINE. (n.d.). Retrieved September 15, 2018, from http://www.thepigsite.com/ focus/advertiser/4499/the-different-breeds-of-swine-philippine-native philippine- native-pig-breed-philippine-native-gilts-sows-and-boars.

THE POTENTIAL IN RAISING NATIVE PIGS. (2016, September 1). PressReader. Retrieved October 8, 2018, from https://www.pressreader.com/philippines/agriculture/20160901/28222660016....

VILLANUEVA, J. J. O., & SULABO, R. C. (2018). Production, Feeding and Marketing Practices of Native Pig Raisers in Selected Regions of the Philippines. Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 7(12), 383–392.

YAP, J. (2017, November 21). NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE PHILIPPINE SWINE INDUSTRY. Retrieved September 19, 2018, from http://agriculture.com.ph/2017/11/21/new-opportunities-for-the-philippin....