ABSTRACT

Contract farming has been in existence for many years as a means of organizing the commercial agricultural production of both large-scale and small-scale farmers. Thailand is one of the pioneers in contract farming in Asia. This article reviews the literature related to contract farming situation in Thailand. Special attention is also given to regulation roles played by the government for contract farming system in Thailand. The findings show that contract farming in Thailand has a long history. It has been instrumental in providing growers access to supply chains with market and price stability, as well as technical assistance. Market and price certainty for both parties and integrated farm-processing enhances the country’s competitiveness via improved quality products and an efficient supply chain. Today the Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017) provides specific rules on the formulation of contracts as well dispute resolution and mediation mechanisms for contract farming system in Thailand. The enhancement of knowledge and awareness of the legal regime applicable to contract farming operations is needed for related agencies, farmers and agaricultural entrepreneurs.

Keywords: Contract Farming, regulation

INTRODUCTION

Market liberalization policies tended to decrease market failures and boost the need for complementary actions to enhance the coordination of market participants. Since then, the transformation of food systems has shifted the focus on how private sector coordination mechanisms can promote access to modern value chains and include farmers in the process of economic growth. Among such coordination systems, contract farming presents an institutional solution to address transaction costs and market failures across commodities, inputs, credit, insurance and information. Contract farming arrangements are increasingly seen as a means to include smallholder farmers in remunerative markets for added value foods that are shaped by urbanization and income growth. Contract farming can also integrate these farmers into markets for export commodities that are driven by the expansion of global agri-food value chains. Moreover, as an institution, contract farming can link farmers to consumers through sophisticated supply chains that add value to food by transport, grading, marketing and processing, ensuring that food meets specific quality and safety requirements (FAO, 2020).

Of all the countries in Asia, Thailand probably has the most extensive experience in contract farming, with the widest range of crops (Glover, 1992). It also has the highest degree of private sector involvement in contract farming and the highest concentration of foreign direct investments in agriculture and agro-industry. Contract farming is a key element of the Thai government's development plan, reflecting a strategy of private-led integrated agricultural development. This new strategy reflects dissatisfaction with both arms length sales in open markets and costly integrated rural development led by the public sector. The strategy proposed is essentially a form of contract farming, in which private firms purchase farmers' output and provide inputs, credit, technical assistance and marketing of the final product (Glover, 1992). In the early stage, the Thai government was heavily involved in monitoring, facilitating and encouraging stakeholders in contractual arrangements. Over time, farmers gained skills, the market evolved, and a more flexible form of contract farming emerged (Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse, 2008). Former contract farmers could negotiate contracts based on their best opportunity till 2017. After the Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017) has been enact since 2017, the contract farming operations need to be under this Act.

Contract farming is generally recognized for its potential to sustain and develop the production sector by contributing to capital formation, technology transfer, increased agricultural production and yields, economic and social development and environmental sustainability. Final consumers, as well as all participants in the supply chain, may also draw substantial benefits from varied and stable sources of raw material supply, and efficient processing and marketing systems (UNIDROIT, FAO and IFAD, 2015). Moreover, contract farming is argued to be a mitigation to deal with the price fluctuation of agricultural commodities. The government, as well as international development agencies such as World Bank and Asian Development Bank, sees contract farming as an effective tool to raise the productivity of agriculture of developing countries, where small-scale farmers are the majority (Richard et al., 2019). However, there are criticisms on the negative impacts of contract farming. These criticisms include concerns about the fairness of economic distribution between small-scale farmers and businesses and its impacts on health and environment (Friend et al., 2019). In Thailand there were also some spectacularly successful examples of this practice, notably in poultry, but there were also many failures (Siamwalla, 1996 and Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse, 2008). There were many studies showing farmer’s socio-economics impact or risk management of contract farming in Thailand (Sribonchitta et al., 1996; Ruangsap, 1997; Ubonchit, 2004; Panchamlong, 2006; Tasanakulphan, 2011; Rakchat, 2011; Ekasingh et al., 2012 and Kitchaicharoen et al., 2014).

However, the purpose of this article is not to replicate past socio-economic studies on the subject of contract farming. Rather, the aim is to provide information on the contarct farming situation in Thailand and highlight the regulation related to contarct farming. This article reviews literature related to contarct farming in Thailand and adds updated information on Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act and its implementation.

SITUATION IN THAILAND: PAST TO PRESENT

Contract farming in Thailand has a long history. In the past, contract farming has been practiced in some form. For example, in 1967 the contract farming in form of agreement was initiated in the tobacco business in Thailand. According to the Tobacco Act of 1966, Thai farmers growing tobacco must sign contracts with the tobacco dryer, and the dryer must sign contracts with the company. This system was practiced in many provinces of the Northern Region. Later, it was used in field crop enterprises, for instance, pineapple plantations in Prachuap Khiri Khan, and poultry farms in Chon Buri Provinces (Makarabhirom and Mochida, 1999). In the mid-1970s the contract farming was first introduced to produce chicken and tomato. Charoen Pokphand (now knowing as Charoen Pokphand Foods Public Company Limited) was the first company that introduced the new biotechnology to grow high-yield broiler and recruited smallholders to grow the new variety of chicken through contract farming in that time. The contract was the effective extension means to recruit small growers to grow a modern variety of chicken, which required new farming knowhow and new arrangements of risk sharing between the growers and the agribusiness company. The contract guaranteed the price and quantity that the company promised to buy, thus providing strong incentive for the growers to join the scheme. As a result, the company has successfully used the non-market vertical coordination to expand its production to satisfy the planned export especially Japan market. The average farm size was 3,000–5,000 birds in the 1980s; it then increased rapidly to 20,000 – 30,000 birds in the early 2000s (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). The scale of operations of companies such as Charoen Pokphand Foods Public Company Limited have enormous significance for what occurs at the scale of rural households involved in contract farming production, and the refashioning of ecological landscapes where such production occurs (Friend et al., 2019).

At the same time in the mid-1970s, Thai government, with assistance from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), encouraged poor rice farmers in the northeast to grow contract tomato for the American company Adam (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). The objective is poverty reduction and to prevent the spread of communism. Contract farming was part of the irrigation development project aimed at generating rural employment and boosting the income of poor rice farmers who could grow only one crop of wet season rice. With irrigation, farmers can grow more than one crop per year. Since then, contract farming has been adopted to produce several products, i.e. vegetables (such as asparagus, baby corn, morning glory, etc.); chili; Japonica rice; corn seed; and others. Perhaps the 1990s and 2000s were the golden era of contract farming. The agricultural census showed that the number of contract farms increased from 0.16 million farms in 1993 to 0.26 million farms in 2003 (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019).

In the 1980s, the government tended to favor the use of contract farming as a means to reduce rural poverty because contract farming allowed farmers to switch from low-value crops such as rice to higher-value products, such as Japonica rice, Basmati rice, exportable vegetables, chicken, etc (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). However, the term ‘contract farming’ only appeared in formal state policy for the first time in the 6th National Economic and Social Development Plan (1987–1991). Under this Plan, the government augmented the so-called Four Sector Cooperation Plan, which includes agrobusinesses, farmers, financial institutions (the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperative – BAAC) and the state agencies. This policy framework provided the platform for early contract farming under the arrangement of the state. Although the Office of Agriculture noted some problems at the end of the 6th National Development Plan, it was recommended that contract farming be further promoted (Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse, 2008). There was no explicit mentioning of contract farming after the 8th National Development Plan (1997-2001), but the government agencies continue to implement this mechanism (Friend et al., 2019).

Contract farming is also widespread in the production of nonfood crops. The longest existing contract farming arrangements is in sugarcane and sugar production (Friend et al., 2019). Sugar factory contracts with farmers directly in form of contract farming and will provide farmers with the necessary inputs and credits to cover their expenses that occur during cultivation and harvesting to promote and support farmers to sell sugarcane to the factory. This contract farming can help reduce market risk for farmers in selling their sugarcane. At the same time, it reduces the risk of raw material procurement of sugar factories (Bank of Thailand, 2021).

Contract farming is also an essential part in securing a stable supply for modern suppliers, while providing reliable income for the farmers’ group. Often the production management plan and good practices are transferred from agribusinesses to farmers under contracts. Contracting community enterprises are allowed to sell vegetables to other wholesalers or suppliers as long as they supply the required order to the contractor first. This extra production volume provides stable sourcing capacity for the contractors and additional income for contracted farmers. Therefore, contract farming provides a formal flow of information and risk sharing between value chain actors (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). Now there are contract farming for other food crops and non-food crops that not mention above such as organic fruit and vegetable, soybean, rambutan, mangosteen, duriun, pineapple, cocoa, herbal, swine, fish, shrimp and energy crop (Depatment of Internal Trade, 2020, Kwankhao et al., 2020; GCF International Co., Ltd, 2021; Cocothai 2017 CO., LTD, 2021 and Bangkok Insight, 2021)

Contract farming can be constructed in a number of ways depending on the crops, the objectives and resources of the contractor and the experience of the farmers. The types of contract farming arrangements could fall into one of 5 models: the centralized model; the nucleus estate model; the multipartite model; the informal model; and the intermediary model. The centralized model is a vertically coordinated model where the sponsor purchases the crop from farmers and processes or packages and markets the product. The nucleus estates are a variation of the centralized model. In this case the sponsor of the project also owns and manages an estate plantation, which is usually close to the processing plant. The multipartite model usually involves statutory bodies and private companies jointly participating with farmers. Multipartite contract farming may have separate organizations responsible for credit provision, production, management, processing and marketing. The infomal model applies to individual entrepreneurs or small companies who normally make simple, informal production contracts with farmers on a seasonal basis, particularly for crops such as fresh vegetables, watermelons and tropical fruits. In intermediary model, sponsor control of material and technical inputs varies widely. The entrepreneurs purchase crops from individual “collectors” or from farmer committees, who have their own informal arrangements with farmers (FAO. 2001). Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse (2005) gave example of the cases of each model in Thailand by using FAO definitions as follows: the centralized model (Thai sugar industry), the nucleus estate model (rice, shrimp, hog and broiler business), the intermediary and multipartite model (the large food processing companies, frozen-vegetable industry and fresh vegetable (soybean, green beans, sweet corn, carrot, spinach, etc.)) and the informal model (vegetable, soybean, tomato, fresh vegetables, cabbage in the remote areas in the north, cut flowers including chemical-free vegetables and chrysanthemum for feeds are contracted for Chiang Mai and Bangkok markets).

CONTRACT FARMING REGULATION IN THAILAND

Before the "Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017)" was enacted, the structure of contract farming system lacked mechanism to involve government organization and suitable legal regulations into the contract farming system. It caused exploitative behavior and making unfair contracts. This greatly affected the economic status of smallholder farmers. At the same time, farmers who entered the system but lacked some capacity and did not comply with the terms of the contract also caused the problems to the business operator in the system. The main problems in contract farming were: 1) information inequality between farmers and companies; 2) inequality in taking risks; 3) inequality in benefit sharing; 4) inequality in law enforcement; and 5) farmers lack potential both in terms of understanding the contract, production capability management, risk management, and farmer group integration. As a result, some farmers did not comply with the terms specified in the contract caused the problems to the business operator in the contract farming system (National Reform Council, 2015).

Contract farming depends on either legal or informal agreements between the contracting parties. These, in turn, has to be backed up by appropriate laws and an efficient legal system. A relevant legal framework and an efficient legal system are preconditions (FAO, 2001). Before the Government of Thailand released Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act to support contract farming in the country in 2017, only Civil and Commercial Code were applicable for contract farming since contract farming could be considered as a contract in which the main focus in hiring is to produce certain product(s). However, the enforcement has limition because contracts in the contract farming system are characterized by a combination of contracts made of hiring, employing and selling agricultural products or providing service, which are complex and difficult to analyze the cost-effectiveness and cost of agricultural produce or services (Ngammuangsakul, 2018). Moreover, production risk and marketing risk of complying with the conditions stipulated in the contract could occur especially in the case where the parties to the contract are smallholders who may be inexperienced, unsophisticated in negotiating contracts, not have easy access to the relevant information surrounding the contract and have less bargaining power in contracts than agricultural business operators. For these reasons, it is necessary to have a specific regulation in order to prescribe rules for contracting in the covenant agricultural system to ensure fairness to all parties, including establishing mechanisms to enhance and develop the contract farming system. This Act can be seen as a tool to convert all the simple registeration and verbal agreement forms of contract farming to be formal agreement. It will also help build trust, cooperation to promote and develop the capacity to produce sustainable agricultural products or services.

Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act

The "Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017)" has come into force since September 2017. If the contract farming is established before the date, this law comes into force, then this law cannot be applied to the contract. In the case where any law specifically provides rules for making contracts and mediation or resolution of disputes with regard to contract farming, the provisions of law on such particular matter shall apply (Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017); Secion 3). In this Act the contract farming means: “the system for the production of agricultural produce or services arising from an agreement for producing the same kind of agricultural produce or services between, on one part, an agricultural business operator and, on the other part, at least ten natural persons who engage in an agricultural occupation or an agricultural co-operative or a group of farmers under the law on co-operatives or a community enterprise or a network of community enterprises under the law on community enterprise promotion, which engages in an agricultural occupation, whereby conditions are fixed as regards the production, distribution or employment for the purpose of producing any agricultural produce or services in a manner that farmers agree to produce, distribute or be employed to produce agricultural produce in accordance with the fixed quantity, quality, price or period of time and the agricultural business operator agrees to purchase such produce or pay remuneration fixed under the agreement, with the agricultural business operator having such involvement in the process of production as fixing methods of production or procuring varieties, seeds, agricultural products or production factors for farmers”

The act provides specific rules on the formulation of contracts as well as dispute resolution and mediation mechanisms in line with guiding principles for responsible contract farming operations of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO). This act is also following the UNIDROIT/FAO/IFAD Legal Guide on Contract that requires the establishment of legislative clarity, determination of remedial measures of the damage to the contract farming system, determination of dispute resolution measures between the parties, determining the powers and duties of government officials and defining important guidelines for the preparation of standard contracts that must be easily understood, be transparent and be able to verify (Ngammuangsakul, 2018). It is divided into several parts, such as Contract Farming Promotion and Development Commission, agricultural business operators, conclusion of contract farming agreements, dispute mediation, penalties and transitory provisions.

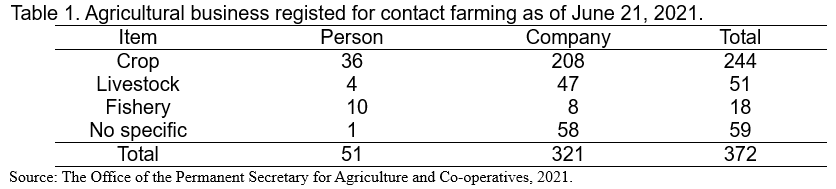

For an agricultural business operator who intends to operate the contract farming business shall notify the operation of business to the Office of the Permanent Secretary for Agriculture and Co-operatives prior to the commencement thereof (Section 16). This office shall prepare a register of agricultural business operators and disclose the same for public inspection, provided that the preparation and disclosure thereof must be made on information systems as well as other media feasibly accessible by the public and the register system must be consistently updated (Section 17). As of June 2021, there are 372 businesses registered under this Act (Table 1).

This Act also establishes a regulatory mechanism to achieve fairness between the parties by forcing the agricultural business operator to prepare a prospectus and a draft agreement in order to enable farmers who will enter into a contract farming agreement to have knowledge thereof in advance and must also certify accuracy of information presented in the prospectus and furnish one copy of such prospectus to the Office of the Permanent Secretary for Agriculture and Co-operatives for retention and reference in the interest of examination. This prospectus shall be deemed to be an integral part of the contract farming agreement. If any statement of an agreement which an agricultural business operator has made with a farmer is contrary to or inconsistent with statements in the prospectus, it shall be construed in favour of the farmer. A contract farming agreement must contain details such as exceptions to contractual performance in the event of force majeure or an unexpected or unavoidable situation beyond control of contractual parties; persons bearing risks in agricultural produce and trade risks in the case where agricultural produce is incapable of distribution at the prices fixed; and contractual parties’ rights to terminate the agreement.

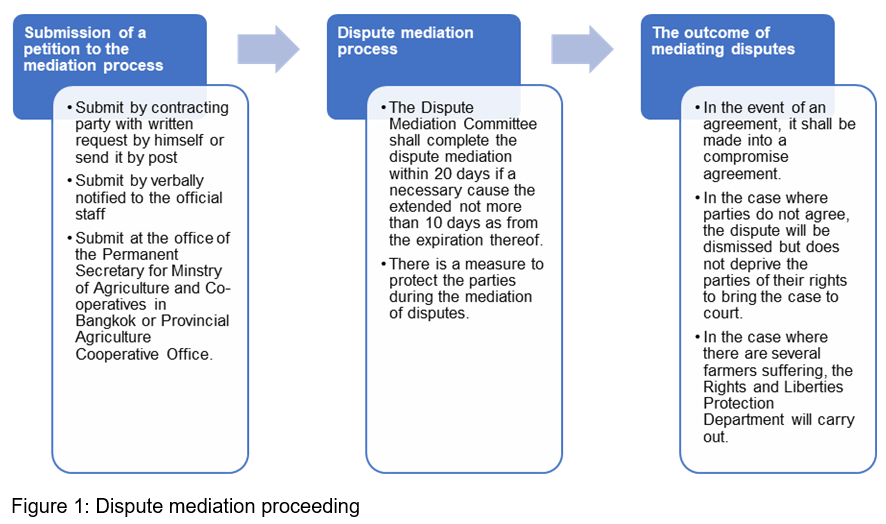

When a dispute arises from the performance of a contract farming agreement, if any party intends to resort to dispute mediation proceedings, both contractual parties shall first embark upon dispute mediation proceedings as provided in this Act before referring the dispute to arbitration or bringing an action before the Court (Section 29).

According to the information on website of the Office of the Secretariat of the Contract Farming System Promotion and Development Committee there have been the cases under dispute mediation process. This shows that this Act establishes the determination of dispute resolution measures between the parties. Eventhough there is some case that the parties do not agree, and the parties could bring their case to the court.

Even though the "Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017)" has come into force for 4 years, there are still challenges for implementation, promotion and development of this Act. For example, the definition of the Contract Farming System in this Act which specially defines that the making contracts are between agricultural business entrepreneurs and at least 10 natural persons who do agricultural occupations is narrower than the total goal of policy to control. This may be the channel for some agricultural business entrepreneurs allotting the contracts or finding other approaches to avoid the access to practice according to this Act (Weeraphan, 2019 and Banmueang, 2016). The legals drafting of Common Law issued according to this Act are also important and must be completed within the time frame determined by the legislation. To manage big data of contract farming including all related document under this Act and to promote the understaning of this Act to relevant agencies, farmers and agriculture entrepreneurs are also challenges (Banmueang, 2016).

CONCLUSION

Contract farming in Thailand has a long history. In the early stage, the government was heavily involved in monitoring, facilitating and encouraging stakeholders in contractual arrangements. Over time, farmers gained skills, the market evolved, and a more flexible form of contract farming emerged. Today the Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017) provides specific rules on the formulation of contracts as well dispute resolution and mediation mechanisms for contract farming systems in Thailand. Understanding how a particular agricultural production contract is regulated under this Act will help parties consider potentially applicable mandatory provisions and default rules, and thus draft better terms for their contract.

REFERENCES

Bangkok Insight. 2021. Contract farming for the sustainable of power plants and communities. https://www.thebangkokinsight.com/news/environmental-sustainability/535808/. [Accessed March 19, 2021]

Bank of Thailand. 2021. Step into a new context of the Thai cane and sugar industry. Bank of Thailand. Northeast branch. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/MonetaryPolicy/NorthEastern/DocLib_Research/0... 1 June 2021(in Thai). [Accessed April 19, 2021]

Banmueang, A. 2016. The Challenges of Implementing the Promotion and Development of Contract Farming System ACT B.E. 2560. An Independent Study submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Political Science, Faculty of Political Science, Thammasat University

CocoaThai 2017 Co., Ltd. 2021. Project to promote cocoa cultivation for sustainable occupation and income of Thai farmers. CocoaThai 2017 Co., Ltd. Thailand. Retrieved from https://www.cocoathai2017.co.th/about-us/. (in Thai). [Accessed March 19, 2021]

Ekasingh, B., Kitchaicharoen, J. and Suebpongsang, P. 2012. Risk in contract farming in Chiangmai and Lumpoon. Thai University for Healthy Public Policy and Thai Health Promotion Foundation.

Department of Internal Trade. 2020. Mangosteen under contract farming. Department of Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand.Department of Internal Trade’s new No.85 8 August 2020.

FAO. 2001. Contract farming Partnerships for growth. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 145. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Room.

FAO. 2020. The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2020. Agricultural markets and sustainable development: Global value chains, smallholder farmers and digital innovations. Rome, FAO. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4060/cb0665en. [Accessed May 19, 2021]

Friend, R.M., Thankappan, S., Doherty, B. et al. 2019. Agricultural and food systems in the Mekong region: Drivers of transformation and pathways of change [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Emerald Open Research 2019, 1:12 Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.12688/emeraldopenres.13104.1 [Accessed March 19, 2021]

GCF International Company Limited. 2021. Pineapple situation in Thailand: 2021 Outlook. GCF International Company Limited, Thailand. Retrieved from https://www.gcfood.com/news/0-13-Pineapple-situation-in-Thailand:-2021-O... 9 February 2021. [Accessed January 23, 2021]

Glover, D. 1992. Introduction. In Contract Farming in Southeast Asia: Three Country Studies, edited by D. Glover and L.T. Ghee. Kuala Lumpur: Institute Pengajian Tinggi/Institute for Advanced Studieshttps://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/10972/91544... [Accessed March 19, 2021]

Kitchaicharoen, J., Suebpongsang, P. and Jittham, V. 2014. Risks, Returns and Adaptation of Farmers in Swine Contract Farming in Northern Thailand presented at The International Conference on the 8th Thailand-Taiwan Bilateral conference and the 2nd UNTA Meeting on Science Technology and Innovation for Sustainable Tropical Agriculture and Food on June 26, 2014 at Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand

Kwankhao, P., Indaratna, K., Anuratpanich, L. and Riewpaiboon, A. 2020. Assessing the outcomes of farmers on promoting herbal medicine use. Pharmaceutical Sciences Asia 2020; 47 (1), 43-50 Retrieved from https://pharmacy.mahidol.ac.th/journal/_files/2020-47-1_043-050.pdf. [Accessed February 1, 2021]

Makarabhirom, P. and Mochida, H. 1999. A study on Contract Tree Farming inThailand. Bull. Tsukuba University No. 15’99. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56641831.pdf. [Accessed March 19, 2021]

National Reform Council. 2015. Special Reform Agenda 9: Reforming the Contract farming System to be Fair. The Secretarial of The Housse of Representatives. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.go.th/ewtadmin/ewt/parliament_parcy/download/parcy/011.pdf [Accessed July 16, 2021]

Ngammuangsakul, U. 2018. Legal Measures for the Protection, Promotion and Development for Contract Farming. Law Journal, Naresuan University. Retrieved from https://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/lawnujournal/article/view/140912/11.... [Accessed June 19, 2021]

Panchamlong, S. 2006. Informal Workers Network, Agricultural contracts and contracts fight against unfair contracts and welfare that have never been received from the state and the capitalists. Project to improve the quality of life of agricultural workers, Contract farming in 4 areas in the northeastern region.Retrieved from http://sathai.org/index.php?option=com_flexicontent&view=items&id=107:co... [Accessed March 1, 2021]

Poapongsakorn, N., Chokesomritpol, P. and Pantakua, K. 2019. Development of Food Value Chains in Thailand. ERIA Research Project Report2018, No. 5. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), Indonesia.

Rakchat, J. 2011. Rural Transformation and Public Policy: Middle-class farmers and landless workers under the Small production: “From farm agriculture to laying hens, commitment: the growth of the agri-food industry”. Chiang Mai : Chiang Mai University

Ruangsap, R. 1997. Potential of contractual agricultural expansion in Chiang Mai Province. Master of Economics. Economics graduate school, Chiang Mai University.

Siamwalla, A. 1996.“Thai Agriculture: From Engine of Growth to Sunset Status”. TDRI Quarterly Review 11, no. 4 (December 1996): 3–10.

Sriboonchitta, S. and Wiboonpoongse, A. 2005. Analysis of Contract Farming in Thailand. Chiang Mai University Journal (2005) Vol.4(3) page 361-382

Sriboonchitta, S. and Wiboonpoongse, A. 2008. Overview of Contract Farming in

Thailand: Lessons learned. ADBI Discussion Paper 112. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank

Institute. Retrieved from http://www.adbi.org/discussion-paper/

2008/07/16/2660.contract.farming.thailand/ [Accessed May 3, 2021]

Sriboonchitta, S., Wiboonpongse, A., Gypmantasiri, P. and Tongngam, K. 1996. Potentials of Contract Farming and Farmer Development Strategies. Bangkok: Institute of Human Resource Development, Thammasat University.

Tasanakulphan, T. 2011. Contract farming and the release of poverty. [Matichon online].

Retrieved from http://www.matichon.co.th/news_ detail.php? newsid=1307455177&grpid&catid=02&subcatid=0207 [Accessed June 7, 2021]

Ubonchit, P. 2004. Economic and Social Changes of Farmers Participating in the Promised Japanese Eggplant Planting Project of Leo Foods Co., Ltd., Chiang Mai Province. Independent research. Master of Science (Agriculture), Department of Agricultural Extension. Chiang Mai University.

UNIDROIT, FAO and IFAD. 2015. Legal Guide on Contract Farming. UNIDROIT/FAO/ IFAD, Rome

Weeraphan, P. 2019. Rights Protection of The Farmer on Contract Farming. Rajapark Journal vol. 13 No.31 October-December 2019 Retrieved from https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/RJPJ/article/view/215044/155182 [Accessed March 20, 2021]

Contract Farming Regulations and Situations in Thailand

ABSTRACT

Contract farming has been in existence for many years as a means of organizing the commercial agricultural production of both large-scale and small-scale farmers. Thailand is one of the pioneers in contract farming in Asia. This article reviews the literature related to contract farming situation in Thailand. Special attention is also given to regulation roles played by the government for contract farming system in Thailand. The findings show that contract farming in Thailand has a long history. It has been instrumental in providing growers access to supply chains with market and price stability, as well as technical assistance. Market and price certainty for both parties and integrated farm-processing enhances the country’s competitiveness via improved quality products and an efficient supply chain. Today the Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017) provides specific rules on the formulation of contracts as well dispute resolution and mediation mechanisms for contract farming system in Thailand. The enhancement of knowledge and awareness of the legal regime applicable to contract farming operations is needed for related agencies, farmers and agaricultural entrepreneurs.

Keywords: Contract Farming, regulation

INTRODUCTION

Market liberalization policies tended to decrease market failures and boost the need for complementary actions to enhance the coordination of market participants. Since then, the transformation of food systems has shifted the focus on how private sector coordination mechanisms can promote access to modern value chains and include farmers in the process of economic growth. Among such coordination systems, contract farming presents an institutional solution to address transaction costs and market failures across commodities, inputs, credit, insurance and information. Contract farming arrangements are increasingly seen as a means to include smallholder farmers in remunerative markets for added value foods that are shaped by urbanization and income growth. Contract farming can also integrate these farmers into markets for export commodities that are driven by the expansion of global agri-food value chains. Moreover, as an institution, contract farming can link farmers to consumers through sophisticated supply chains that add value to food by transport, grading, marketing and processing, ensuring that food meets specific quality and safety requirements (FAO, 2020).

Of all the countries in Asia, Thailand probably has the most extensive experience in contract farming, with the widest range of crops (Glover, 1992). It also has the highest degree of private sector involvement in contract farming and the highest concentration of foreign direct investments in agriculture and agro-industry. Contract farming is a key element of the Thai government's development plan, reflecting a strategy of private-led integrated agricultural development. This new strategy reflects dissatisfaction with both arms length sales in open markets and costly integrated rural development led by the public sector. The strategy proposed is essentially a form of contract farming, in which private firms purchase farmers' output and provide inputs, credit, technical assistance and marketing of the final product (Glover, 1992). In the early stage, the Thai government was heavily involved in monitoring, facilitating and encouraging stakeholders in contractual arrangements. Over time, farmers gained skills, the market evolved, and a more flexible form of contract farming emerged (Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse, 2008). Former contract farmers could negotiate contracts based on their best opportunity till 2017. After the Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017) has been enact since 2017, the contract farming operations need to be under this Act.

Contract farming is generally recognized for its potential to sustain and develop the production sector by contributing to capital formation, technology transfer, increased agricultural production and yields, economic and social development and environmental sustainability. Final consumers, as well as all participants in the supply chain, may also draw substantial benefits from varied and stable sources of raw material supply, and efficient processing and marketing systems (UNIDROIT, FAO and IFAD, 2015). Moreover, contract farming is argued to be a mitigation to deal with the price fluctuation of agricultural commodities. The government, as well as international development agencies such as World Bank and Asian Development Bank, sees contract farming as an effective tool to raise the productivity of agriculture of developing countries, where small-scale farmers are the majority (Richard et al., 2019). However, there are criticisms on the negative impacts of contract farming. These criticisms include concerns about the fairness of economic distribution between small-scale farmers and businesses and its impacts on health and environment (Friend et al., 2019). In Thailand there were also some spectacularly successful examples of this practice, notably in poultry, but there were also many failures (Siamwalla, 1996 and Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse, 2008). There were many studies showing farmer’s socio-economics impact or risk management of contract farming in Thailand (Sribonchitta et al., 1996; Ruangsap, 1997; Ubonchit, 2004; Panchamlong, 2006; Tasanakulphan, 2011; Rakchat, 2011; Ekasingh et al., 2012 and Kitchaicharoen et al., 2014).

However, the purpose of this article is not to replicate past socio-economic studies on the subject of contract farming. Rather, the aim is to provide information on the contarct farming situation in Thailand and highlight the regulation related to contarct farming. This article reviews literature related to contarct farming in Thailand and adds updated information on Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act and its implementation.

SITUATION IN THAILAND: PAST TO PRESENT

Contract farming in Thailand has a long history. In the past, contract farming has been practiced in some form. For example, in 1967 the contract farming in form of agreement was initiated in the tobacco business in Thailand. According to the Tobacco Act of 1966, Thai farmers growing tobacco must sign contracts with the tobacco dryer, and the dryer must sign contracts with the company. This system was practiced in many provinces of the Northern Region. Later, it was used in field crop enterprises, for instance, pineapple plantations in Prachuap Khiri Khan, and poultry farms in Chon Buri Provinces (Makarabhirom and Mochida, 1999). In the mid-1970s the contract farming was first introduced to produce chicken and tomato. Charoen Pokphand (now knowing as Charoen Pokphand Foods Public Company Limited) was the first company that introduced the new biotechnology to grow high-yield broiler and recruited smallholders to grow the new variety of chicken through contract farming in that time. The contract was the effective extension means to recruit small growers to grow a modern variety of chicken, which required new farming knowhow and new arrangements of risk sharing between the growers and the agribusiness company. The contract guaranteed the price and quantity that the company promised to buy, thus providing strong incentive for the growers to join the scheme. As a result, the company has successfully used the non-market vertical coordination to expand its production to satisfy the planned export especially Japan market. The average farm size was 3,000–5,000 birds in the 1980s; it then increased rapidly to 20,000 – 30,000 birds in the early 2000s (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). The scale of operations of companies such as Charoen Pokphand Foods Public Company Limited have enormous significance for what occurs at the scale of rural households involved in contract farming production, and the refashioning of ecological landscapes where such production occurs (Friend et al., 2019).

At the same time in the mid-1970s, Thai government, with assistance from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), encouraged poor rice farmers in the northeast to grow contract tomato for the American company Adam (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). The objective is poverty reduction and to prevent the spread of communism. Contract farming was part of the irrigation development project aimed at generating rural employment and boosting the income of poor rice farmers who could grow only one crop of wet season rice. With irrigation, farmers can grow more than one crop per year. Since then, contract farming has been adopted to produce several products, i.e. vegetables (such as asparagus, baby corn, morning glory, etc.); chili; Japonica rice; corn seed; and others. Perhaps the 1990s and 2000s were the golden era of contract farming. The agricultural census showed that the number of contract farms increased from 0.16 million farms in 1993 to 0.26 million farms in 2003 (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019).

In the 1980s, the government tended to favor the use of contract farming as a means to reduce rural poverty because contract farming allowed farmers to switch from low-value crops such as rice to higher-value products, such as Japonica rice, Basmati rice, exportable vegetables, chicken, etc (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). However, the term ‘contract farming’ only appeared in formal state policy for the first time in the 6th National Economic and Social Development Plan (1987–1991). Under this Plan, the government augmented the so-called Four Sector Cooperation Plan, which includes agrobusinesses, farmers, financial institutions (the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperative – BAAC) and the state agencies. This policy framework provided the platform for early contract farming under the arrangement of the state. Although the Office of Agriculture noted some problems at the end of the 6th National Development Plan, it was recommended that contract farming be further promoted (Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse, 2008). There was no explicit mentioning of contract farming after the 8th National Development Plan (1997-2001), but the government agencies continue to implement this mechanism (Friend et al., 2019).

Contract farming is also widespread in the production of nonfood crops. The longest existing contract farming arrangements is in sugarcane and sugar production (Friend et al., 2019). Sugar factory contracts with farmers directly in form of contract farming and will provide farmers with the necessary inputs and credits to cover their expenses that occur during cultivation and harvesting to promote and support farmers to sell sugarcane to the factory. This contract farming can help reduce market risk for farmers in selling their sugarcane. At the same time, it reduces the risk of raw material procurement of sugar factories (Bank of Thailand, 2021).

Contract farming is also an essential part in securing a stable supply for modern suppliers, while providing reliable income for the farmers’ group. Often the production management plan and good practices are transferred from agribusinesses to farmers under contracts. Contracting community enterprises are allowed to sell vegetables to other wholesalers or suppliers as long as they supply the required order to the contractor first. This extra production volume provides stable sourcing capacity for the contractors and additional income for contracted farmers. Therefore, contract farming provides a formal flow of information and risk sharing between value chain actors (Poapongsakorn et al., 2019). Now there are contract farming for other food crops and non-food crops that not mention above such as organic fruit and vegetable, soybean, rambutan, mangosteen, duriun, pineapple, cocoa, herbal, swine, fish, shrimp and energy crop (Depatment of Internal Trade, 2020, Kwankhao et al., 2020; GCF International Co., Ltd, 2021; Cocothai 2017 CO., LTD, 2021 and Bangkok Insight, 2021)

Contract farming can be constructed in a number of ways depending on the crops, the objectives and resources of the contractor and the experience of the farmers. The types of contract farming arrangements could fall into one of 5 models: the centralized model; the nucleus estate model; the multipartite model; the informal model; and the intermediary model. The centralized model is a vertically coordinated model where the sponsor purchases the crop from farmers and processes or packages and markets the product. The nucleus estates are a variation of the centralized model. In this case the sponsor of the project also owns and manages an estate plantation, which is usually close to the processing plant. The multipartite model usually involves statutory bodies and private companies jointly participating with farmers. Multipartite contract farming may have separate organizations responsible for credit provision, production, management, processing and marketing. The infomal model applies to individual entrepreneurs or small companies who normally make simple, informal production contracts with farmers on a seasonal basis, particularly for crops such as fresh vegetables, watermelons and tropical fruits. In intermediary model, sponsor control of material and technical inputs varies widely. The entrepreneurs purchase crops from individual “collectors” or from farmer committees, who have their own informal arrangements with farmers (FAO. 2001). Sriboonchitta and Wiboonpoongse (2005) gave example of the cases of each model in Thailand by using FAO definitions as follows: the centralized model (Thai sugar industry), the nucleus estate model (rice, shrimp, hog and broiler business), the intermediary and multipartite model (the large food processing companies, frozen-vegetable industry and fresh vegetable (soybean, green beans, sweet corn, carrot, spinach, etc.)) and the informal model (vegetable, soybean, tomato, fresh vegetables, cabbage in the remote areas in the north, cut flowers including chemical-free vegetables and chrysanthemum for feeds are contracted for Chiang Mai and Bangkok markets).

CONTRACT FARMING REGULATION IN THAILAND

Before the "Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017)" was enacted, the structure of contract farming system lacked mechanism to involve government organization and suitable legal regulations into the contract farming system. It caused exploitative behavior and making unfair contracts. This greatly affected the economic status of smallholder farmers. At the same time, farmers who entered the system but lacked some capacity and did not comply with the terms of the contract also caused the problems to the business operator in the system. The main problems in contract farming were: 1) information inequality between farmers and companies; 2) inequality in taking risks; 3) inequality in benefit sharing; 4) inequality in law enforcement; and 5) farmers lack potential both in terms of understanding the contract, production capability management, risk management, and farmer group integration. As a result, some farmers did not comply with the terms specified in the contract caused the problems to the business operator in the contract farming system (National Reform Council, 2015).

Contract farming depends on either legal or informal agreements between the contracting parties. These, in turn, has to be backed up by appropriate laws and an efficient legal system. A relevant legal framework and an efficient legal system are preconditions (FAO, 2001). Before the Government of Thailand released Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act to support contract farming in the country in 2017, only Civil and Commercial Code were applicable for contract farming since contract farming could be considered as a contract in which the main focus in hiring is to produce certain product(s). However, the enforcement has limition because contracts in the contract farming system are characterized by a combination of contracts made of hiring, employing and selling agricultural products or providing service, which are complex and difficult to analyze the cost-effectiveness and cost of agricultural produce or services (Ngammuangsakul, 2018). Moreover, production risk and marketing risk of complying with the conditions stipulated in the contract could occur especially in the case where the parties to the contract are smallholders who may be inexperienced, unsophisticated in negotiating contracts, not have easy access to the relevant information surrounding the contract and have less bargaining power in contracts than agricultural business operators. For these reasons, it is necessary to have a specific regulation in order to prescribe rules for contracting in the covenant agricultural system to ensure fairness to all parties, including establishing mechanisms to enhance and develop the contract farming system. This Act can be seen as a tool to convert all the simple registeration and verbal agreement forms of contract farming to be formal agreement. It will also help build trust, cooperation to promote and develop the capacity to produce sustainable agricultural products or services.

Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act

The "Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017)" has come into force since September 2017. If the contract farming is established before the date, this law comes into force, then this law cannot be applied to the contract. In the case where any law specifically provides rules for making contracts and mediation or resolution of disputes with regard to contract farming, the provisions of law on such particular matter shall apply (Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017); Secion 3). In this Act the contract farming means: “the system for the production of agricultural produce or services arising from an agreement for producing the same kind of agricultural produce or services between, on one part, an agricultural business operator and, on the other part, at least ten natural persons who engage in an agricultural occupation or an agricultural co-operative or a group of farmers under the law on co-operatives or a community enterprise or a network of community enterprises under the law on community enterprise promotion, which engages in an agricultural occupation, whereby conditions are fixed as regards the production, distribution or employment for the purpose of producing any agricultural produce or services in a manner that farmers agree to produce, distribute or be employed to produce agricultural produce in accordance with the fixed quantity, quality, price or period of time and the agricultural business operator agrees to purchase such produce or pay remuneration fixed under the agreement, with the agricultural business operator having such involvement in the process of production as fixing methods of production or procuring varieties, seeds, agricultural products or production factors for farmers”

The act provides specific rules on the formulation of contracts as well as dispute resolution and mediation mechanisms in line with guiding principles for responsible contract farming operations of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO). This act is also following the UNIDROIT/FAO/IFAD Legal Guide on Contract that requires the establishment of legislative clarity, determination of remedial measures of the damage to the contract farming system, determination of dispute resolution measures between the parties, determining the powers and duties of government officials and defining important guidelines for the preparation of standard contracts that must be easily understood, be transparent and be able to verify (Ngammuangsakul, 2018). It is divided into several parts, such as Contract Farming Promotion and Development Commission, agricultural business operators, conclusion of contract farming agreements, dispute mediation, penalties and transitory provisions.

For an agricultural business operator who intends to operate the contract farming business shall notify the operation of business to the Office of the Permanent Secretary for Agriculture and Co-operatives prior to the commencement thereof (Section 16). This office shall prepare a register of agricultural business operators and disclose the same for public inspection, provided that the preparation and disclosure thereof must be made on information systems as well as other media feasibly accessible by the public and the register system must be consistently updated (Section 17). As of June 2021, there are 372 businesses registered under this Act (Table 1).

This Act also establishes a regulatory mechanism to achieve fairness between the parties by forcing the agricultural business operator to prepare a prospectus and a draft agreement in order to enable farmers who will enter into a contract farming agreement to have knowledge thereof in advance and must also certify accuracy of information presented in the prospectus and furnish one copy of such prospectus to the Office of the Permanent Secretary for Agriculture and Co-operatives for retention and reference in the interest of examination. This prospectus shall be deemed to be an integral part of the contract farming agreement. If any statement of an agreement which an agricultural business operator has made with a farmer is contrary to or inconsistent with statements in the prospectus, it shall be construed in favour of the farmer. A contract farming agreement must contain details such as exceptions to contractual performance in the event of force majeure or an unexpected or unavoidable situation beyond control of contractual parties; persons bearing risks in agricultural produce and trade risks in the case where agricultural produce is incapable of distribution at the prices fixed; and contractual parties’ rights to terminate the agreement.

When a dispute arises from the performance of a contract farming agreement, if any party intends to resort to dispute mediation proceedings, both contractual parties shall first embark upon dispute mediation proceedings as provided in this Act before referring the dispute to arbitration or bringing an action before the Court (Section 29).

According to the information on website of the Office of the Secretariat of the Contract Farming System Promotion and Development Committee there have been the cases under dispute mediation process. This shows that this Act establishes the determination of dispute resolution measures between the parties. Eventhough there is some case that the parties do not agree, and the parties could bring their case to the court.

Even though the "Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017)" has come into force for 4 years, there are still challenges for implementation, promotion and development of this Act. For example, the definition of the Contract Farming System in this Act which specially defines that the making contracts are between agricultural business entrepreneurs and at least 10 natural persons who do agricultural occupations is narrower than the total goal of policy to control. This may be the channel for some agricultural business entrepreneurs allotting the contracts or finding other approaches to avoid the access to practice according to this Act (Weeraphan, 2019 and Banmueang, 2016). The legals drafting of Common Law issued according to this Act are also important and must be completed within the time frame determined by the legislation. To manage big data of contract farming including all related document under this Act and to promote the understaning of this Act to relevant agencies, farmers and agriculture entrepreneurs are also challenges (Banmueang, 2016).

CONCLUSION

Contract farming in Thailand has a long history. In the early stage, the government was heavily involved in monitoring, facilitating and encouraging stakeholders in contractual arrangements. Over time, farmers gained skills, the market evolved, and a more flexible form of contract farming emerged. Today the Contract Farming Promotion and Development Act B.E. 2560 (2017) provides specific rules on the formulation of contracts as well dispute resolution and mediation mechanisms for contract farming systems in Thailand. Understanding how a particular agricultural production contract is regulated under this Act will help parties consider potentially applicable mandatory provisions and default rules, and thus draft better terms for their contract.

REFERENCES

Bangkok Insight. 2021. Contract farming for the sustainable of power plants and communities. https://www.thebangkokinsight.com/news/environmental-sustainability/535808/. [Accessed March 19, 2021]

Bank of Thailand. 2021. Step into a new context of the Thai cane and sugar industry. Bank of Thailand. Northeast branch. Retrieved from https://www.bot.or.th/Thai/MonetaryPolicy/NorthEastern/DocLib_Research/0... 1 June 2021(in Thai). [Accessed April 19, 2021]

Banmueang, A. 2016. The Challenges of Implementing the Promotion and Development of Contract Farming System ACT B.E. 2560. An Independent Study submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Political Science, Faculty of Political Science, Thammasat University

CocoaThai 2017 Co., Ltd. 2021. Project to promote cocoa cultivation for sustainable occupation and income of Thai farmers. CocoaThai 2017 Co., Ltd. Thailand. Retrieved from https://www.cocoathai2017.co.th/about-us/. (in Thai). [Accessed March 19, 2021]

Ekasingh, B., Kitchaicharoen, J. and Suebpongsang, P. 2012. Risk in contract farming in Chiangmai and Lumpoon. Thai University for Healthy Public Policy and Thai Health Promotion Foundation.

Department of Internal Trade. 2020. Mangosteen under contract farming. Department of Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand.Department of Internal Trade’s new No.85 8 August 2020.

FAO. 2001. Contract farming Partnerships for growth. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 145. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Room.

FAO. 2020. The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2020. Agricultural markets and sustainable development: Global value chains, smallholder farmers and digital innovations. Rome, FAO. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4060/cb0665en. [Accessed May 19, 2021]

Friend, R.M., Thankappan, S., Doherty, B. et al. 2019. Agricultural and food systems in the Mekong region: Drivers of transformation and pathways of change [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Emerald Open Research 2019, 1:12 Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.12688/emeraldopenres.13104.1 [Accessed March 19, 2021]

GCF International Company Limited. 2021. Pineapple situation in Thailand: 2021 Outlook. GCF International Company Limited, Thailand. Retrieved from https://www.gcfood.com/news/0-13-Pineapple-situation-in-Thailand:-2021-O... 9 February 2021. [Accessed January 23, 2021]

Glover, D. 1992. Introduction. In Contract Farming in Southeast Asia: Three Country Studies, edited by D. Glover and L.T. Ghee. Kuala Lumpur: Institute Pengajian Tinggi/Institute for Advanced Studieshttps://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/10972/91544... [Accessed March 19, 2021]

Kitchaicharoen, J., Suebpongsang, P. and Jittham, V. 2014. Risks, Returns and Adaptation of Farmers in Swine Contract Farming in Northern Thailand presented at The International Conference on the 8th Thailand-Taiwan Bilateral conference and the 2nd UNTA Meeting on Science Technology and Innovation for Sustainable Tropical Agriculture and Food on June 26, 2014 at Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand

Kwankhao, P., Indaratna, K., Anuratpanich, L. and Riewpaiboon, A. 2020. Assessing the outcomes of farmers on promoting herbal medicine use. Pharmaceutical Sciences Asia 2020; 47 (1), 43-50 Retrieved from https://pharmacy.mahidol.ac.th/journal/_files/2020-47-1_043-050.pdf. [Accessed February 1, 2021]

Makarabhirom, P. and Mochida, H. 1999. A study on Contract Tree Farming inThailand. Bull. Tsukuba University No. 15’99. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56641831.pdf. [Accessed March 19, 2021]

National Reform Council. 2015. Special Reform Agenda 9: Reforming the Contract farming System to be Fair. The Secretarial of The Housse of Representatives. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.go.th/ewtadmin/ewt/parliament_parcy/download/parcy/011.pdf [Accessed July 16, 2021]

Ngammuangsakul, U. 2018. Legal Measures for the Protection, Promotion and Development for Contract Farming. Law Journal, Naresuan University. Retrieved from https://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/lawnujournal/article/view/140912/11.... [Accessed June 19, 2021]

Panchamlong, S. 2006. Informal Workers Network, Agricultural contracts and contracts fight against unfair contracts and welfare that have never been received from the state and the capitalists. Project to improve the quality of life of agricultural workers, Contract farming in 4 areas in the northeastern region.Retrieved from http://sathai.org/index.php?option=com_flexicontent&view=items&id=107:co... [Accessed March 1, 2021]

Poapongsakorn, N., Chokesomritpol, P. and Pantakua, K. 2019. Development of Food Value Chains in Thailand. ERIA Research Project Report2018, No. 5. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), Indonesia.

Rakchat, J. 2011. Rural Transformation and Public Policy: Middle-class farmers and landless workers under the Small production: “From farm agriculture to laying hens, commitment: the growth of the agri-food industry”. Chiang Mai : Chiang Mai University

Ruangsap, R. 1997. Potential of contractual agricultural expansion in Chiang Mai Province. Master of Economics. Economics graduate school, Chiang Mai University.

Siamwalla, A. 1996.“Thai Agriculture: From Engine of Growth to Sunset Status”. TDRI Quarterly Review 11, no. 4 (December 1996): 3–10.

Sriboonchitta, S. and Wiboonpoongse, A. 2005. Analysis of Contract Farming in Thailand. Chiang Mai University Journal (2005) Vol.4(3) page 361-382

Sriboonchitta, S. and Wiboonpoongse, A. 2008. Overview of Contract Farming in

Thailand: Lessons learned. ADBI Discussion Paper 112. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank

Institute. Retrieved from http://www.adbi.org/discussion-paper/

2008/07/16/2660.contract.farming.thailand/ [Accessed May 3, 2021]

Sriboonchitta, S., Wiboonpongse, A., Gypmantasiri, P. and Tongngam, K. 1996. Potentials of Contract Farming and Farmer Development Strategies. Bangkok: Institute of Human Resource Development, Thammasat University.

Tasanakulphan, T. 2011. Contract farming and the release of poverty. [Matichon online].

Retrieved from http://www.matichon.co.th/news_ detail.php? newsid=1307455177&grpid&catid=02&subcatid=0207 [Accessed June 7, 2021]

Ubonchit, P. 2004. Economic and Social Changes of Farmers Participating in the Promised Japanese Eggplant Planting Project of Leo Foods Co., Ltd., Chiang Mai Province. Independent research. Master of Science (Agriculture), Department of Agricultural Extension. Chiang Mai University.

UNIDROIT, FAO and IFAD. 2015. Legal Guide on Contract Farming. UNIDROIT/FAO/ IFAD, Rome

Weeraphan, P. 2019. Rights Protection of The Farmer on Contract Farming. Rajapark Journal vol. 13 No.31 October-December 2019 Retrieved from https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/RJPJ/article/view/215044/155182 [Accessed March 20, 2021]