The local people in Yanbye Township, Rakhine State have been practicing the conversion of mangroves for rice production since primordial times. World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Japanese Government supported funding for the conversion of mangrove areas for rice production in 1979 and 1985 (Stanley et al., 2011). Farm plots which are converted from mangrove forest to grow rice or for fishery are locally called ‘Kari.’ The Kari is a type of collective farm where two or many households work together for construction of farm plots, farming and sharing of the products fairly among member households.

FARMING PROCEDURE AND FARMING CALENDAR OF RICE-KARI

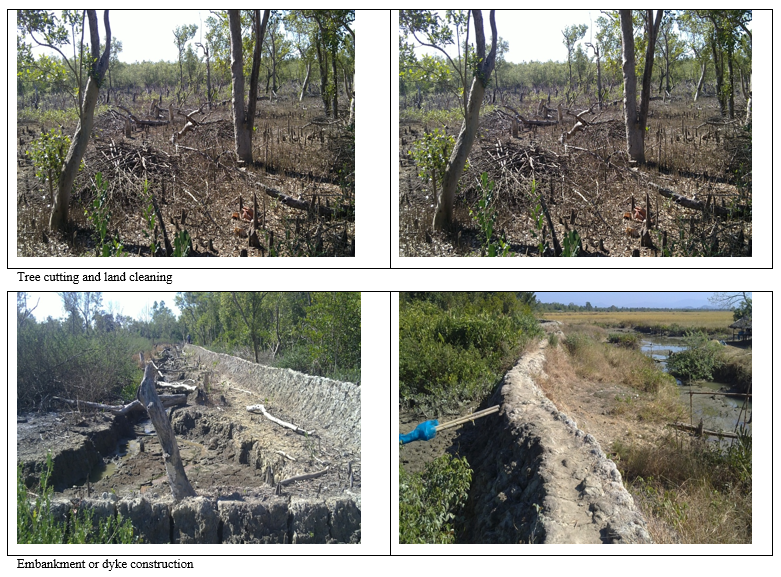

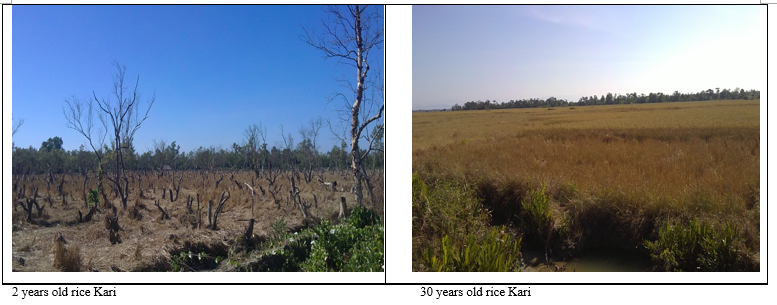

Farm plots are established by cutting down mangrove trees and constructing embankments around the plot to stop the tide water to flow inside. The embankments are made from 1-2 m high and 0.5-1 m thick. Rain water is collected in the first year to reduce the salinity of soil. Without tide, water mangrove trees cannot grow well and will soon die off in the later year.

Except for the first two years of farm establishment, farmers work in Kari for about six months in a production year. The peak season of farm work lasts usually for three months at the time of rice sowing and harvesting: June to August as sowing time and the other three months (December to February) as the season of harvesting. According to the tidal conditions, there are 15 working days per month. Farmers are able to work in the farms during the time of spring tide (high tide), which occurs during the time of the full moon and new moon days. The time for rising and falling of tides lasts 6 hours alternately. Normally, working hours for a farmer in their farms is 8 hours a day.

Farming activities and production practices are different in the first six years from the following years of production. Construction of dikes, clearing trees and vegetation are the major activities in the first two years and rice is grown by seed broadcasting during first five years. Ploughing, harrowing, and transplanting of rice seedlings are practiced in the sixth and the following years. Mostly farmer households work in Karis collectively and share the product evenly among them.

State Kari

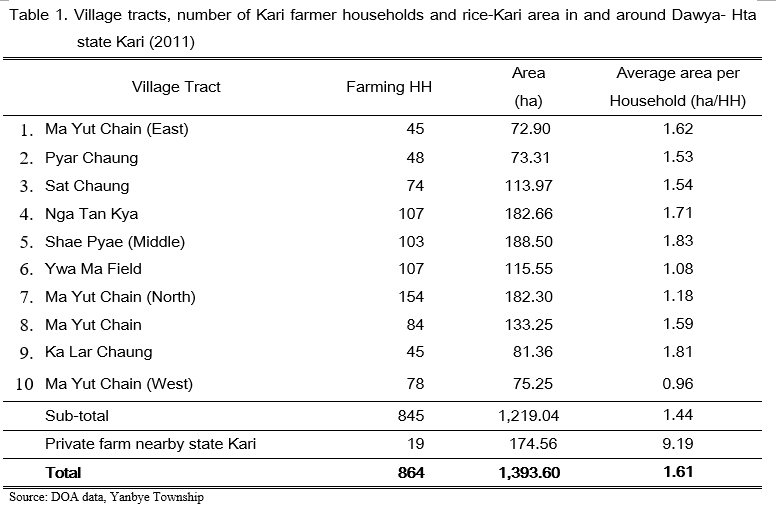

In 1966, the government established Dawya- Hta Kari in Ma-Yut- Chain Village Tract, on the left-side bench of Yambye Creek along the middle coast of the Ka Lain Taung River, for the purpose of increased rice production in the region to fulfill the demand of local rice consumption. The Department of Irrigation mechanically constructed the dike with four main sluice gates to prevent tidewater entering into the field, and the irrigation and drainage channels for rice growing. The construction was finished in 1972-73 with the 22.45 km length covering 1,699.38 ha of arable land, and 80.60 ha of rice production which were started in the same year. The rice-growing area increased every year to 1,445.85 ha in 1987-88 (Tin Shwe, 1990) and 1,393.61 ha in 2011-12 (DOA, 2012). In state Kari, each household has an average 1.44 ha of farmlands and they cannot expand the area of the land nor can they change land use for shrimp farming. Following Dawya- Hta Kari, however, local people constructed 174.56 ha of small private Kari around for rice farming. In 2011, 864 households conducted rice farming in and around the state Kari sharing of 1.61 ha of farmland per household (Table 1).

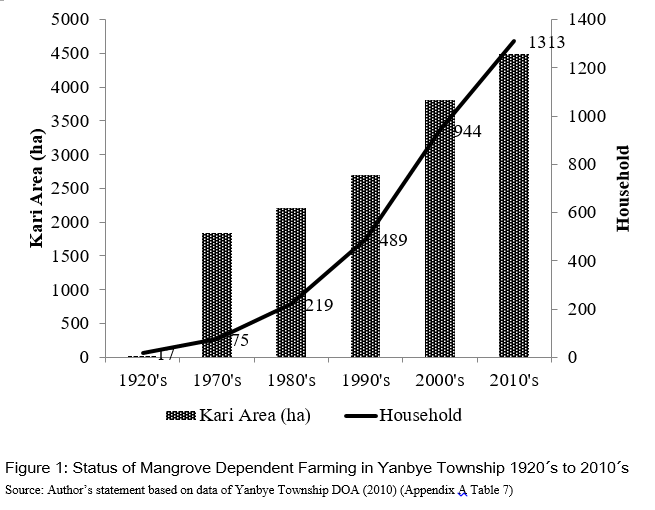

Figure 1 presents the area of mangrove dependent farming in Yanbye Township from the 1920s to 2010s. The increasing trend of Kari area and the number of households working in the Kari can be seen every 10 years after 1970s. The encroachment of farming into the mangroves has been increasing over time. The most rapid increase was found from 1990 to 2000. Between 2000 and 2010, the rate of increase was 67 ha per year. The household population that practiced rice-Kari also increased five times within a 40 year period.

Private Rice Kari

Private Kari can be found mostly in Alae Chaung, Kyauk Saut, Kala Bone village tracts near the riverbank of Thanzit river; Yan Thit Kyi, Yan Thit Chae, Latt Pan, Ma Yut Chain, Thinbaw Sait, Wat Keit Chaung, Pyin Chaung Kyi, Maybone, Lamu Chae, Hone Wa village tracts near the Ka Lain Taung River Bank.

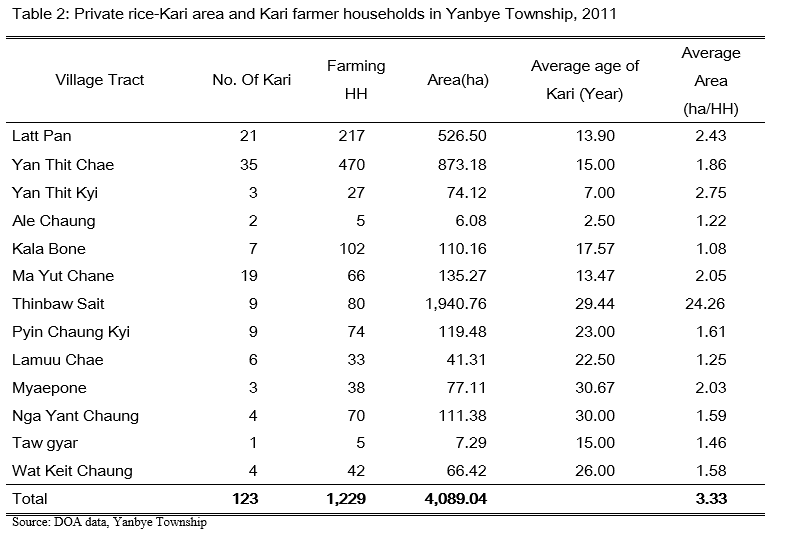

In 1987-88, there were 62 private Kari that covered 1,473.39 ha of rice farms (Tin Shwe, 1999). According to data of the DOA Yanbye office (shown in Table 2) the establishment of private Kari began 90 years ago and continued to expand every year until 2011.

In private Kari, local people worked together in groups of two to 40 households in a specific Kari and both rice farming and shrimp farming were labor intensive. There were 123 private rice-Kari plots where 1,229 households from 13 village tracts were working in 2011. On average, each household in the private rice-Kari had 3.33 ha of Kari farm. There was no restriction of area expansion and crop production and, therefore some farmers cultivated rice continuously while some practiced rotation of rice and shrimp farming.

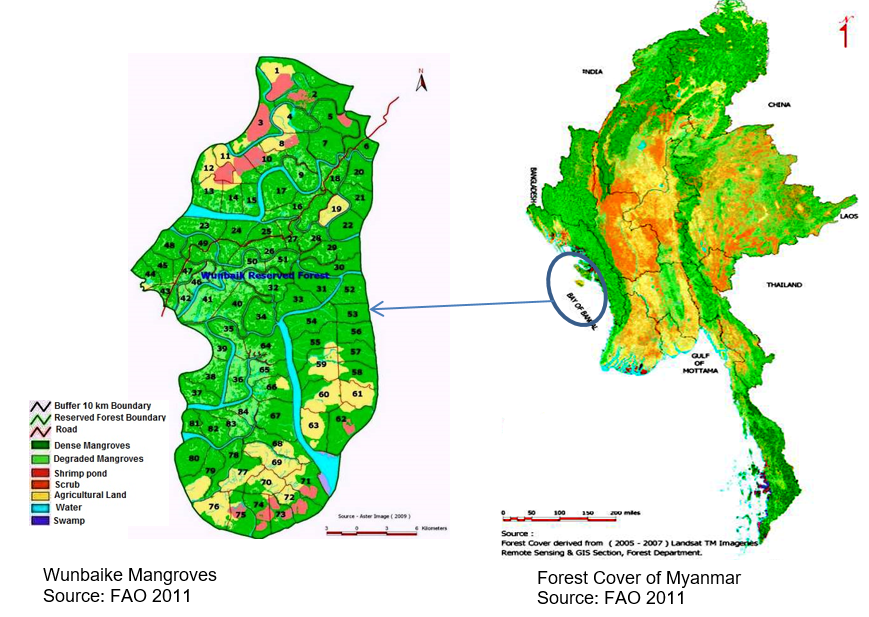

RICE KARI IN WUNBAIKE MANGROVE FOREST

Like nearby mangroves, Wunbaike mangrove forest is attractive for Kari construction despite the fact that it is a reserved forest. There are no clear official or ground data to present when the agriculture or aquaculture encroachment in Wunbaike reserved forest began. During the FAO project (2010-2011), land use change of Wunbaike mangrove forest for 1990 to 2011 was observed by the application of Remote Sensing and GIS techniques. The analysis of satellite imagery showed there were 611 ha of encroachment area for agriculture and aquaculture in 1990. Further encroachments took place in the following decades and reached 4,639 ha in 2011, and represented 22.21% of total rice growing area in Yanbye Township.

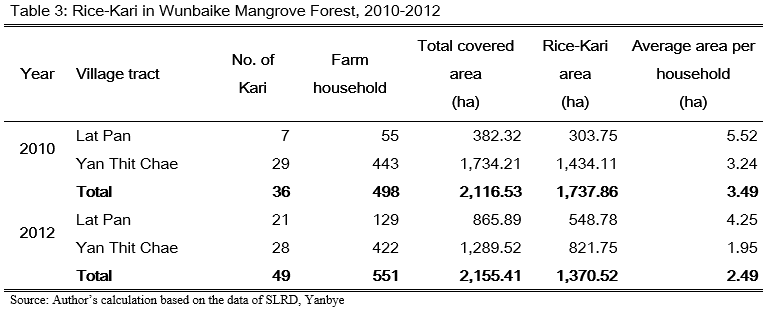

The ‘total covered area’ means the area of the mangrove forest cleaned for rice farming including land area for paths among the plots, drainage channels, and temporary huts. ‘Rice-Kari’ is the actual rice growing area and it occupied 80% of protected area. Farming in WMF occupied two village tracts. In 2010, 498 farmer households grew 1,737.86 ha that occupied 8.56% of total rice growing area of the whole township. The average rice-Kari area holding per household was 3.49 ha.

The number of rice-Kari increased by 13 plots and farming households increased by 53 in 2012 compared to 2010, although the farming area decreased to 1,370.52 ha (8.32% of total township rice growing area) and average land holding was also reduced to 2.49 ha. Due to the nature of the open access of the land, and where land ownership is not clear and systematic, it is difficult to estimate the number of farm households and actual farming area every year. In fact, Kari is a kind of convenient collective farming by a group of a number of households. Although farming is usually conducted in a plot by a fixed group of farmer households, in some years some households could have left the group or some other households could have joined the group.

CONTRIBUTION OF RICE-KARI TO RICE PRODUCTION

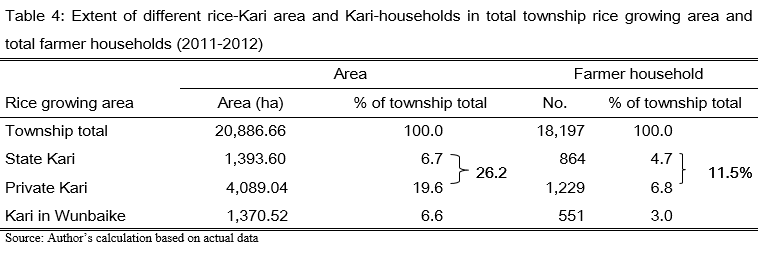

Table 4 presents the distribution of rice-Kari area and number of Kari-farmer households in total township rice production area and total rice farmers. From the official reported data, the mangrove dependent rice growing area occupied 26.2% of township rice areas in total while 19.6% of it is private Kari. The rice area in Wunbaike mangroves occupied 6.6 % of township total rice production area. In terms of number of households dependent on rice area, 11.5 % of the township’s total rice farmers were from private Kari sector while 3% of them worked in the Wunbaike mangrove forest.

The mangrove area in Wunbaike mangroves in Table 4 may be a minimum estimate because, official data for encroached rice-Kari area is usually underestimated due to non-compliance in reporting actual data and because there was no actual measurement of rice-Kari in reserved mangroves. For example, if the data of rice-Kari which is 173,786 ha in 2010 was used, the area of rice-Kari in Wunbaike Mangrove becomes 8.3% of township total rice growing area.

Mangrove dependent rice production supplied occupied 29% of township total rice production. The rice- in Wunbaike Mangrove Forest alone supplied 7% of the whole township production.

AGRICULTURAL AND FOREST POLICY CONCERN

With its contribution of about 28% to country’s GDP, Myanmar’s agricultural sector adopted the strategy of expansion of new agricultural land for its enhancement. Rice production and fishery sectors classify mangroves as cultivable wastelands. Mangrove forests were converted to agricultural land including shrimp farming for domestic consumption and exports. These development projects have led to severe destruction of mangroves around the country. The total area of mangroves, estimated at 531,000 ha in 1980, fell to 312,443 ha in 2010 (FD statistics, 2010). Annual loss of mangrove area over the period 1975 to 2005 was estimated at 1% (Giri et al., 2011). Ayeyearwaddy mangroves was one the biggest mangroves area of the country,

In terms of forest management policies, the Forest Law 1992 and the Forest Act 1995 were promulgated for management and conservation purposes for all kinds of forests in the country. These forest laws establish protected forests, including the conservation of mangrove forests, and biodiversity. Under the forest laws, mangroves are protected forests and sometimes declared as forests to supply the fuel requirement, and for sustainable extraction of non-timber forest products. The forest department of Yanbye takes responsibility for establishment of forest plantations, establishment of forest nurseries, distribution of forest plant seedlings to local peoples, reforestation in mangroves, conservation of forests, restrictions and taking actions on illegal forest product extraction (FD report, 2011). In 2010 to 2011, the department was also collaborating with FAO for the project ‘Sustainable Community Based Mangrove Management in Wunbaike Forest Reserve’. During the FAO project in 2010-11, several options for alternative income generation were introduced to the region. Training on teak nursery operation, gardening and propagation of fruit trees, intensive backyard vegetable growing were demonstrated during the project period. However, these activities were conducted only in representative members from three selected model villages Latpan Awa, Yanthitshae, Hlaing Khaung. Fuel-efficient stove production was introduced in those villages to reduce dependency on mangroves for fuel wood production.

The enforcement of rules and regulations for mangroves conservation is laidback, while the application of agricultural policies is inconsistent with the forest laws. As a result, mangrove areas continue to be exploited and destroyed at unsustainable rates. This phenomenon obviously indicates that mangroves are undervalued in decision-making and policy formulation in Myanmar.

CONCLUSION

Farming in Wunbaike Mangroves plays an apparent role in regional food production. However, Ecosystem value of mangroves vanish with this system. Promoting agriculture may be the solution to reduce the extent of mangrove product extraction. Agricultural development policies, however, should be implemented together with the legislative appraisal in order to prevent the further conversion of mangroves to other development activities. Conservation of Wunbaike Mangrove Forest with local community development should be initiated before the mangrove area is totally exploited and the region becomes vulnerable. The Forest Department and policy makers should consider exerting more effort on reforestation and rehabilitation of mangroves in the region.

REFERENCES

Aye, H.K. (2007). Sustainable Mangrove Forest management, Wunbaike Mangrove area, Yanbyae Towhship. Rakhine State, Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Department of Geology, Yangon University.

Stanley, D., Broadhead, J. and Myint, A. (2011). The Atlas and Guidelines for Mangrove Management in Wunbaik Reserved Forest, UNFAO, Myanmar Publication 2011/04

Giri, C., Ochieng, E., Tieszen, L. L., Zhu, Z., Singh, A., Loveland, T., and Duke, N. (2011). Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 20(1), 154-159.San, Cho Cho (2018), Economic Assessment of Mangorve Forest Uses: The Case of Wunbaike Mangrove Forest in Rakhine State, Myanmar, kassel university press, ISBN: 978-3-7376-0108-5, 2017, URN: urn:nbn:de:0002-401099 DOI: 10.19211/kup9783737601092

Soe, K. M.and Stanley, D. (2011). Fishery Resources of The Wunbaik, Reserved Mangrove Forest, UN, Myanmar Publication 2011/04.

Oo, N. W. (2002). Present state and problems of mangrove management in Myanmar. Trees 16, 218-223.

Forest Sector Annual Report, Yambye Township Forest Department (FD) (2011), Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation.

Forest Department statistics ( 2010), Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation.

Mangroves-dependent Traditional Farming System in Yambye Township, Rakhine State

The local people in Yanbye Township, Rakhine State have been practicing the conversion of mangroves for rice production since primordial times. World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Japanese Government supported funding for the conversion of mangrove areas for rice production in 1979 and 1985 (Stanley et al., 2011). Farm plots which are converted from mangrove forest to grow rice or for fishery are locally called ‘Kari.’ The Kari is a type of collective farm where two or many households work together for construction of farm plots, farming and sharing of the products fairly among member households.

FARMING PROCEDURE AND FARMING CALENDAR OF RICE-KARI

Farm plots are established by cutting down mangrove trees and constructing embankments around the plot to stop the tide water to flow inside. The embankments are made from 1-2 m high and 0.5-1 m thick. Rain water is collected in the first year to reduce the salinity of soil. Without tide, water mangrove trees cannot grow well and will soon die off in the later year.

Except for the first two years of farm establishment, farmers work in Kari for about six months in a production year. The peak season of farm work lasts usually for three months at the time of rice sowing and harvesting: June to August as sowing time and the other three months (December to February) as the season of harvesting. According to the tidal conditions, there are 15 working days per month. Farmers are able to work in the farms during the time of spring tide (high tide), which occurs during the time of the full moon and new moon days. The time for rising and falling of tides lasts 6 hours alternately. Normally, working hours for a farmer in their farms is 8 hours a day.

Farming activities and production practices are different in the first six years from the following years of production. Construction of dikes, clearing trees and vegetation are the major activities in the first two years and rice is grown by seed broadcasting during first five years. Ploughing, harrowing, and transplanting of rice seedlings are practiced in the sixth and the following years. Mostly farmer households work in Karis collectively and share the product evenly among them.

State Kari

In 1966, the government established Dawya- Hta Kari in Ma-Yut- Chain Village Tract, on the left-side bench of Yambye Creek along the middle coast of the Ka Lain Taung River, for the purpose of increased rice production in the region to fulfill the demand of local rice consumption. The Department of Irrigation mechanically constructed the dike with four main sluice gates to prevent tidewater entering into the field, and the irrigation and drainage channels for rice growing. The construction was finished in 1972-73 with the 22.45 km length covering 1,699.38 ha of arable land, and 80.60 ha of rice production which were started in the same year. The rice-growing area increased every year to 1,445.85 ha in 1987-88 (Tin Shwe, 1990) and 1,393.61 ha in 2011-12 (DOA, 2012). In state Kari, each household has an average 1.44 ha of farmlands and they cannot expand the area of the land nor can they change land use for shrimp farming. Following Dawya- Hta Kari, however, local people constructed 174.56 ha of small private Kari around for rice farming. In 2011, 864 households conducted rice farming in and around the state Kari sharing of 1.61 ha of farmland per household (Table 1).

Figure 1 presents the area of mangrove dependent farming in Yanbye Township from the 1920s to 2010s. The increasing trend of Kari area and the number of households working in the Kari can be seen every 10 years after 1970s. The encroachment of farming into the mangroves has been increasing over time. The most rapid increase was found from 1990 to 2000. Between 2000 and 2010, the rate of increase was 67 ha per year. The household population that practiced rice-Kari also increased five times within a 40 year period.

Private Rice Kari

Private Kari can be found mostly in Alae Chaung, Kyauk Saut, Kala Bone village tracts near the riverbank of Thanzit river; Yan Thit Kyi, Yan Thit Chae, Latt Pan, Ma Yut Chain, Thinbaw Sait, Wat Keit Chaung, Pyin Chaung Kyi, Maybone, Lamu Chae, Hone Wa village tracts near the Ka Lain Taung River Bank.

In 1987-88, there were 62 private Kari that covered 1,473.39 ha of rice farms (Tin Shwe, 1999). According to data of the DOA Yanbye office (shown in Table 2) the establishment of private Kari began 90 years ago and continued to expand every year until 2011.

In private Kari, local people worked together in groups of two to 40 households in a specific Kari and both rice farming and shrimp farming were labor intensive. There were 123 private rice-Kari plots where 1,229 households from 13 village tracts were working in 2011. On average, each household in the private rice-Kari had 3.33 ha of Kari farm. There was no restriction of area expansion and crop production and, therefore some farmers cultivated rice continuously while some practiced rotation of rice and shrimp farming.

RICE KARI IN WUNBAIKE MANGROVE FOREST

Like nearby mangroves, Wunbaike mangrove forest is attractive for Kari construction despite the fact that it is a reserved forest. There are no clear official or ground data to present when the agriculture or aquaculture encroachment in Wunbaike reserved forest began. During the FAO project (2010-2011), land use change of Wunbaike mangrove forest for 1990 to 2011 was observed by the application of Remote Sensing and GIS techniques. The analysis of satellite imagery showed there were 611 ha of encroachment area for agriculture and aquaculture in 1990. Further encroachments took place in the following decades and reached 4,639 ha in 2011, and represented 22.21% of total rice growing area in Yanbye Township.

The ‘total covered area’ means the area of the mangrove forest cleaned for rice farming including land area for paths among the plots, drainage channels, and temporary huts. ‘Rice-Kari’ is the actual rice growing area and it occupied 80% of protected area. Farming in WMF occupied two village tracts. In 2010, 498 farmer households grew 1,737.86 ha that occupied 8.56% of total rice growing area of the whole township. The average rice-Kari area holding per household was 3.49 ha.

The number of rice-Kari increased by 13 plots and farming households increased by 53 in 2012 compared to 2010, although the farming area decreased to 1,370.52 ha (8.32% of total township rice growing area) and average land holding was also reduced to 2.49 ha. Due to the nature of the open access of the land, and where land ownership is not clear and systematic, it is difficult to estimate the number of farm households and actual farming area every year. In fact, Kari is a kind of convenient collective farming by a group of a number of households. Although farming is usually conducted in a plot by a fixed group of farmer households, in some years some households could have left the group or some other households could have joined the group.

CONTRIBUTION OF RICE-KARI TO RICE PRODUCTION

Table 4 presents the distribution of rice-Kari area and number of Kari-farmer households in total township rice production area and total rice farmers. From the official reported data, the mangrove dependent rice growing area occupied 26.2% of township rice areas in total while 19.6% of it is private Kari. The rice area in Wunbaike mangroves occupied 6.6 % of township total rice production area. In terms of number of households dependent on rice area, 11.5 % of the township’s total rice farmers were from private Kari sector while 3% of them worked in the Wunbaike mangrove forest.

The mangrove area in Wunbaike mangroves in Table 4 may be a minimum estimate because, official data for encroached rice-Kari area is usually underestimated due to non-compliance in reporting actual data and because there was no actual measurement of rice-Kari in reserved mangroves. For example, if the data of rice-Kari which is 173,786 ha in 2010 was used, the area of rice-Kari in Wunbaike Mangrove becomes 8.3% of township total rice growing area.

Mangrove dependent rice production supplied occupied 29% of township total rice production. The rice- in Wunbaike Mangrove Forest alone supplied 7% of the whole township production.

AGRICULTURAL AND FOREST POLICY CONCERN

With its contribution of about 28% to country’s GDP, Myanmar’s agricultural sector adopted the strategy of expansion of new agricultural land for its enhancement. Rice production and fishery sectors classify mangroves as cultivable wastelands. Mangrove forests were converted to agricultural land including shrimp farming for domestic consumption and exports. These development projects have led to severe destruction of mangroves around the country. The total area of mangroves, estimated at 531,000 ha in 1980, fell to 312,443 ha in 2010 (FD statistics, 2010). Annual loss of mangrove area over the period 1975 to 2005 was estimated at 1% (Giri et al., 2011). Ayeyearwaddy mangroves was one the biggest mangroves area of the country,

In terms of forest management policies, the Forest Law 1992 and the Forest Act 1995 were promulgated for management and conservation purposes for all kinds of forests in the country. These forest laws establish protected forests, including the conservation of mangrove forests, and biodiversity. Under the forest laws, mangroves are protected forests and sometimes declared as forests to supply the fuel requirement, and for sustainable extraction of non-timber forest products. The forest department of Yanbye takes responsibility for establishment of forest plantations, establishment of forest nurseries, distribution of forest plant seedlings to local peoples, reforestation in mangroves, conservation of forests, restrictions and taking actions on illegal forest product extraction (FD report, 2011). In 2010 to 2011, the department was also collaborating with FAO for the project ‘Sustainable Community Based Mangrove Management in Wunbaike Forest Reserve’. During the FAO project in 2010-11, several options for alternative income generation were introduced to the region. Training on teak nursery operation, gardening and propagation of fruit trees, intensive backyard vegetable growing were demonstrated during the project period. However, these activities were conducted only in representative members from three selected model villages Latpan Awa, Yanthitshae, Hlaing Khaung. Fuel-efficient stove production was introduced in those villages to reduce dependency on mangroves for fuel wood production.

The enforcement of rules and regulations for mangroves conservation is laidback, while the application of agricultural policies is inconsistent with the forest laws. As a result, mangrove areas continue to be exploited and destroyed at unsustainable rates. This phenomenon obviously indicates that mangroves are undervalued in decision-making and policy formulation in Myanmar.

CONCLUSION

Farming in Wunbaike Mangroves plays an apparent role in regional food production. However, Ecosystem value of mangroves vanish with this system. Promoting agriculture may be the solution to reduce the extent of mangrove product extraction. Agricultural development policies, however, should be implemented together with the legislative appraisal in order to prevent the further conversion of mangroves to other development activities. Conservation of Wunbaike Mangrove Forest with local community development should be initiated before the mangrove area is totally exploited and the region becomes vulnerable. The Forest Department and policy makers should consider exerting more effort on reforestation and rehabilitation of mangroves in the region.

REFERENCES

Aye, H.K. (2007). Sustainable Mangrove Forest management, Wunbaike Mangrove area, Yanbyae Towhship. Rakhine State, Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Department of Geology, Yangon University.

Stanley, D., Broadhead, J. and Myint, A. (2011). The Atlas and Guidelines for Mangrove Management in Wunbaik Reserved Forest, UNFAO, Myanmar Publication 2011/04

Giri, C., Ochieng, E., Tieszen, L. L., Zhu, Z., Singh, A., Loveland, T., and Duke, N. (2011). Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 20(1), 154-159.San, Cho Cho (2018), Economic Assessment of Mangorve Forest Uses: The Case of Wunbaike Mangrove Forest in Rakhine State, Myanmar, kassel university press, ISBN: 978-3-7376-0108-5, 2017, URN: urn:nbn:de:0002-401099 DOI: 10.19211/kup9783737601092

Soe, K. M.and Stanley, D. (2011). Fishery Resources of The Wunbaik, Reserved Mangrove Forest, UN, Myanmar Publication 2011/04.

Oo, N. W. (2002). Present state and problems of mangrove management in Myanmar. Trees 16, 218-223.

Forest Sector Annual Report, Yambye Township Forest Department (FD) (2011), Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation.

Forest Department statistics ( 2010), Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation.