ABSTRACT

Black gram is an economically important pulse in Myanmar and mainly exported to India. In August 2017, India announced a 200,000 tons import quota on pigeon peas and 150,000 tons quota each for black gram and green gram. This study aimed to analyze the determinants on profitability of black gram production before and after India’s import suspension. Total 120 sample farm households were chosen by using a simple random sampling method from six villages in Kyauktaga Township. Descriptive, cost and return, and regression analyses were employed. The findings indicated that after import suspension, the effective price of black gram was significantly decreased and benefit-cost ratio before import suspension was about double than after import suspension. Effective price of black gram, sown area, age of household heads, hired labor cost and numbers of credit sources were significantly influenced on profit of black gram production before import suspension. The same factors, except age of household heads, significantly determined the profit of black gram production after import suspension. In addition, access to extension service was positively and significantly influenced on profit after import suspension. Thus, research and extension services should pay attention to improve knowledge and information of alternative crops substitution. Because credit sources are important for profitability of black gram farmers, access to more credits from different sources should be facilitated.

Key words: black gram, before and after India’s import suspension, Bago Region, Myanmar.

INTRODUCTION

Pulses are attractive to farmers because they have lower production costs and better returns in comparison with other crops in Myanmar. Pulses contribute the major export portion among Myanmar’s agricultural export products. Major exportable pulses are black gram, green gram, pigeon pea, chickpea, soybean, butter bean, cowpea and kidney bean (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation [MOALI], 2018). Black gram, green gram and pigeon pea accounted for 70% of total pulses production. About 91% of total pigeon pea production and 77% of total black gram are exported to India and the domestic wholesale prices depend almost entirely on India’s demand (Department of Agriculture [DOA], 2017). Another exported pulse, green gram is exported to many countries including India, China, Indonesia, Malaysia and UAE.

Black gram (Vigna mungo) is the second largest cultivated pulse crop in Myanmar. It is cultivated in both monsoon and winter seasons and mainly planted after monsoon paddy on residual moisture. Bago Region is the largest cultivated area and production, followed by Ayeyawady and Sagaing Regions in 2017-2018 (DOA, 2018). In August 2017, India announced a 200,000 tons import quota on pigeon peas and 150,000 tons quota each for black gram and green gram. That time was two months before harvesting of the pigeon peas, and before planting time of black gram and green gram in Myanmar. India’s import restrictions which limited the amount of pea products from Myanmar have quickly and adversely affected the local pulses market in Myanmar (Thit, 2017). Therefore, this study was conducted to know how much the profit has been changed and the determining factors on the profitability of black gram production before and after India’s pulse import suspension.

Research methodology

Kyauktaga Township was chosen as the study area because of the largest cultivated area of black gram in Bago Region during 2016-2017 (DOA, 2017). Both primary and secondary data were used in this study. The primary information was collected from 120 sample farmers of six villages by personal interview with a structured questionnaire using simple random sampling method. The survey was conducted in January, 2019 after India’s import suspension in August, 2017. Descriptive statistics, cost and return analysis, and regression analysis were used with Microsoft excel and STATA 12 statistical software to fulfill the research objectives.

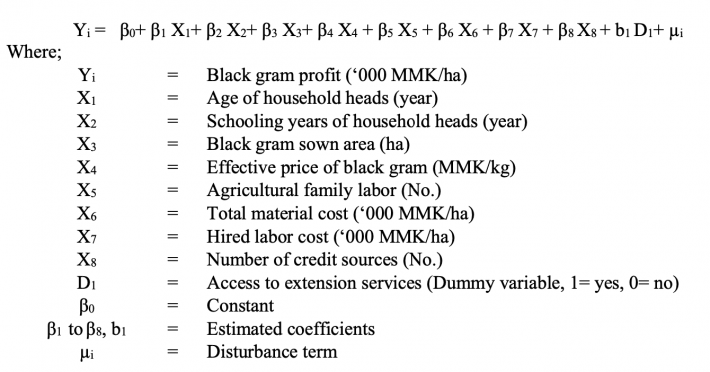

To determine the factors affecting profit of black gram production before and after import suspension in the study area, linear regression function was used. The regression function was as follows;

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic characteristics of sample farm households

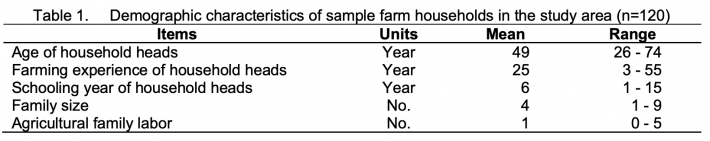

Demographic characteristics of sample farm households were described in Table 1. The average age of household heads was 49 years within a range of 26 to 74 years. Farmers had 25 years of farming experience on average ranging from a minimum of 3 years to a maximum of 55 years. As the educational status, the average schooling years of farmers was middle school level (6 years). The maximum schooling years were 15 and the minimum was 1. The average family size of the sample farm households was 4. The maximum number of family members was 9 and minimum was one person. The average agricultural family labor of sample households was 1 within the range of no agricultural family labor to maximum 5 agricultural family labors.

Access to agricultural extension services before and after import suspension

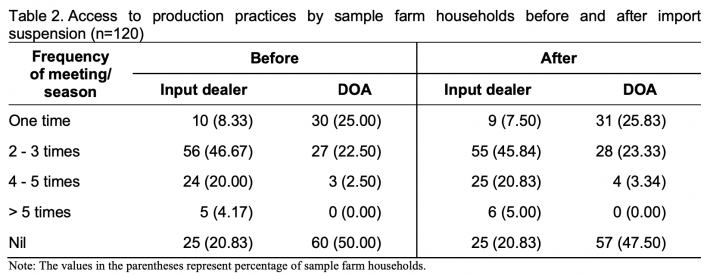

Sample farmers received information related to black gram production practices from different sources such as private agro-input company and DOA. Table 2 presented that the sample households’ meeting attendance offered by private agro-input company and DOA. Before the restriction, about 20.83% and 50.00% of farmers had no contact with private and government extension agents. The attendance of extension training or meeting of farm households offered by private company and DOA was 8.33% and 25.00% for one time, 46.67% and 22.50% for two to three times and 20.00% and 2.50% for four to five times respectively. About 4.17% of farmers attended the meeting above five times by private company per season.

After the restriction, about 20.83% and 47.50 % of farm households had no contact with private and DOA extension agents. About 7.50% and 25.83% of farmers participated only one time in the agricultural extension meeting by private and government organizations. The attendance of extension meeting accessible by private company and DOA was 45.84% and 23.33% for two to three times and 20.83% and 3.34% for four to five times respectively. The contact time to extension agents above five times had 5.00% by private company.

Sources of credit taken by sample farm households before and after import suspension

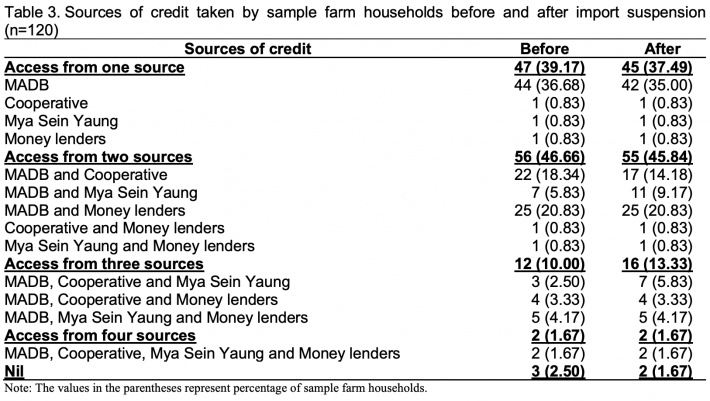

According to survey data, MADB was the main credit source and about 36.68% of sample farm households received credit only from MADB as well as about 2.49% of sample farm households received from cooperative, Mya Sein Yaung (Evergreen project) and money lenders before the restriction (Table 3). About 20.83% of sample farm households received credit from two sources (MADB and money lenders), followed by MADB and cooperative, and MADB and Mya Sein Yaung before the restriction. About 10.00% of farmers received credit from three sources and about 1.67% of farmers received from four sources while about 2.50% of sample farm households did not take the credit before the restriction.

After the restriction, about 35.00% of sample farm households received credit from MADB and about 2.49% of sample farm households received credit from cooperative, Mya Sein Yaung and money lenders. About 20.83% of sample farm households received from MADB and money lenders, followed by MADB and cooperative, and MADB and Mya Sein Yaung. The percentage of sample farm households received credit from cooperative and money lenders, and Mya Sein Yaung and money lenders were not different after the restriction. About 13.33% of farmers received credit from three sources and the percentage of farmers received from four sources was not changed while only 1.67% of sample farm households did not take the credit after the restriction.

Changes in cultivated area and gross annual crop incomes by sample farm households before and after import suspension

Changes in cultivated areas by sample farm households before and after import suspension were shown in Table 4. According to results, all sample farmers cultivated monsoon rice and their cultivated areas were not significantly different before and after suspension. The number of black gram farmers decreased from 120 to 111 farmers and cultivated areas of black gram were significantly decreased from 3.17 ha to 2.66 ha at 10% level before and after suspension. The number of farmers cultivated green gram, cowpea and sesame crops increased but the number of farmers grown groundnut and other pulses (pae ni lay) were the same. The cultivated areas of green gram were significantly increased from 0.59 ha to 1.12 ha at 1% level after import suspension and that of groundnut, cowpeas, sesame and other pulses were not significantly different as compared to before and after import suspension. Thus, green gram was cultivated increasingly instead of black gram after import restriction.

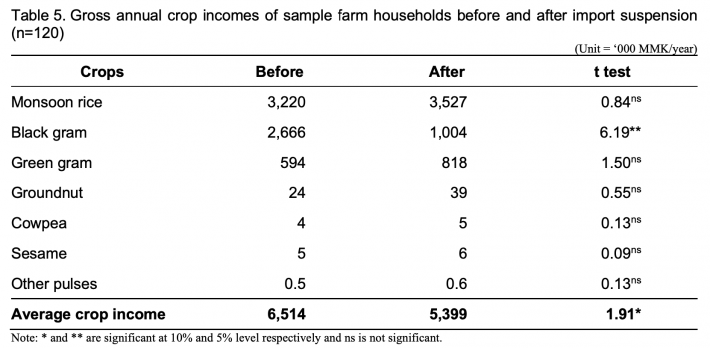

Gross annual incomes of cultivated crops by sample farm households before and after import suspension were presented in Table 5. Monsoon rice was the main income source and the average amount of monsoon rice income increased from 3.22 to 3.52 million MMK per year before and after import suspension. Average black gram income was significantly decreased from 2.66 to 1.00 million MMK per year at 5% level before and after import suspension. Other crop incomes received from green gram, groundnut, cowpea, sesame and other pulses were increased but not significantly different before and after import suspension.

Black gram production of sample farm households before and after import suspension

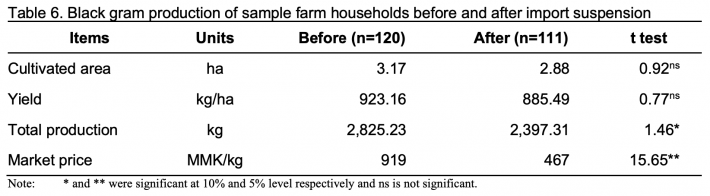

According to survey results, sample farm households cultivated about an average of 3.17 ha of black gram before import suspension and decreased to 2.88 ha after import suspension (Table 6). Mean yield was decreased from 923.16 kg/ha to 885.49 kg/ha after import suspension. There were no significant differences in cultivated areas and yield between two years. Average total production of black gram was significantly decreased from 2,825.23 kg to 2,397.31 kg at 10% level after import suspension. Market price of black gram was decreased from 919 MMK/kg to 467 MMK/kg and it was significantly different at 5% level before and after import suspension.

Cost and return analysis of black gram production before and after import suspension

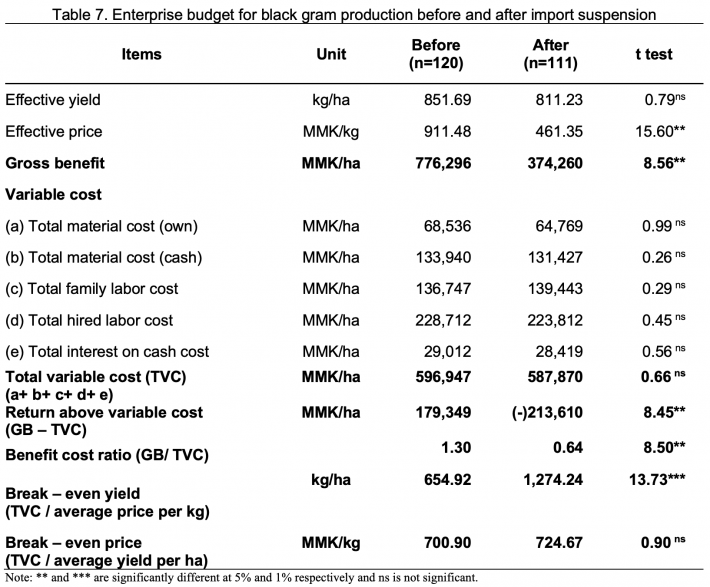

The enterprise budget was used to compare cost and return of black gram production before and after import suspension. Various measures of costs and returns were reported in Table 7. Effective black gram yield of sample farmers (851.69 kg/ha) before the restriction was slightly higher than that of sample farmers (811.23 kg/ha) after the restriction. Effective price of black gram (911.48 MMK/kg) before the restriction was also significantly higher than (461.35 MMK/kg) after the restriction. Therefore, average gross benefit before the restriction (776,296 MMK/ha) was significantly greater than after the restriction (374,260 MMK/ha). There were significantly different in price and gross benefit of black gram at 5% level before and after import suspension.

Total material cost included farmers’ owned materials such as seed and FYM, and bought materials such as seed, urea, compound, foliar fertilizer, herbicide, fungicide and insecticide. Costs for farmers’ owned materials were 68,536 MMK/ha and 64,769 MMK/ha respectively before and after import suspension. Material costs expended by farmers were 133,940 MMK/ha before import suspension and 131,427 MMK/ha after import suspension. Average total family labor cost were 136,747 MMK/ha and 139,443 MMK/ha before and after import suspension. It was expensed for hired labor cost of 228,712 MMK/ha and 223,812 MMK/ha respectively before and after the restriction. In the total interest cost on cash cost, farm households expended 29,012 MMK/ha and 28,419 MMK/ha respectively before and after import suspension. The total variable costs were 596,947 MMK/ha and 587,870 MMK/ha respectively before and after import suspension. There were not significantly different in all variable costs while comparing before and after import suspension.

Return above variable cost (RAVC) before the restriction was 179,349 MMK/ha and (-) 213,610 MMK/ha after the restriction. Hence, the benefit-cost ratios (BCRs) were 1.30 and 0.64 respectively before and after import suspension. They were significantly different in benefit-cost ratios at 5% level before and after import suspension. Therefore, it can be concluded that sample farm households received more profit before import restriction. The important reason for farmers receiving a larger profit before the restriction was that they got higher prices though total variable costs before the restriction was slightly higher than that of after restriction period.

Break-even yield for black gram production were 654.92 kg/ha and 1,274.24 kg/ha whereas break-even price were 700.90 MMK/kg and 724.67 MMK/kg respectively before and after import suspension. It was significantly different in break-even yield for black gram production at 1% level before and after import suspension.

Factors affecting the profitability of black gram production before and after import suspension

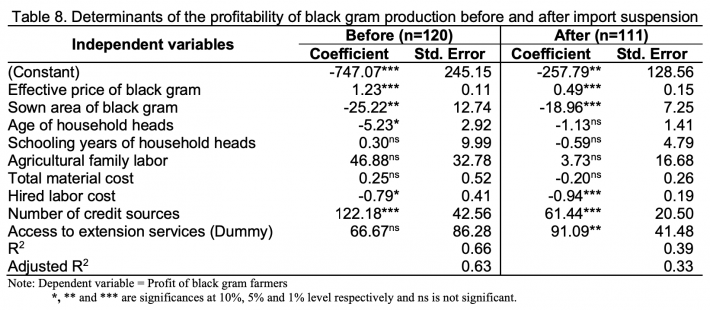

Black gram profit regression estimates before and after import suspension was described in Table 8. According to results before import suspension, the significant influencing factors of black gram profit were effective price of black gram, sown area of black gram, age of household heads, hired labor cost and number of credit sources. Black gram profit was positively correlated with effective price of black gram and number of credit sources at 1% level. It means that if price of black gram 1 MMK increased, black gram profit would be increased by 1,230 MMK per hectare and if the credit received by sample farmers in black gram production one source increased, black gram profit would be increased by 122,180 MMK per hectare. The result showed that if farmers received higher price, they would pay more attention in black gram production to get high income so price directly effects on profit and the government would be provided credit program to the farmers in black gram production. Black gram profit was negatively correlated with sown area of black gram at 5% level, age of household heads at 10% level and hired labor cost at 10% level respectively. If farmers cultivated black gram one hectare increased, the profit would be decreased by 25,220 MMK per hectare. The result showed that if cultivated area of black gram was increased, farmers would pay a lesser attention on management of black gram production. If farmers’ age one year older, they did not follow the technology in black gram production and therefore, profit will be decreased by 5,230 MMK per hectare. If hired labor cost of 1,000 MMK increased in black gram production in the study area, black gram profit would be decreased by 790 MMK per hectare. The result showed that the farmers who had suffered high cost of hired labor on the farm in black gram production could receive low profit. The adjusted R squared points out that the model is significant and it can explain the variation in black gram profit by 63 percent.

After import suspension, the same factors and the same trend except age of household heads were significantly determined the profit of black gram production at 1% level. In addition, access to extension service was also positively influenced on profit of black gram production at 5% level. If price of black gram 1 MMK increased, black gram profit would be increased by 490 MMK per hectare and if the credit received by sample farmers in black gram production one source increased, black gram profit would be increased by 61,440 MMK per hectare. If farmers cultivated black gram one hectare increased, the profit would be decreased by 18,960 MMK per hectare. If hired labor cost of 1,000 MMK increased in black gram production in the study area, black gram profit would be decreased by 940 MMK per hectare. This dummy variable, access to extension services (yes=1, no=0) specified that profit of black gram production by sample farmers who had received extension services was 91,090 MMK more than that farmers who did not receive extension services. Therefore, extension service is becoming much important for farmers after risk due to import suspension. The adjusted R squared points out that the model is significant and it can explain the variation in black gram profit by 33%.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

According to result findings, farmers had productive experiences and better potential for decision making in black gram production because they spent half of their lives in farming. Although they had many experiences in farming, India’s import suspension had negative effects on black gram farmers. Low demand from India by import suspension was a pulled factor for lower price in black gram domestic market. The cultivated areas decreased in black gram and increased in green gram significantly in the study area. Some farmers tried to solve by substituting green gram instead of black gram because green gram was exported to many other countries. Although MOALI recommended sunflower cultivation to sufficient domestic oil consumption, sample farmers have not yet cultivated sunflower in the study area. In the study area, there were very few economically alternative substitute crops and therefore, research and development are required for alternative crop substitution.

According to BCRs result, sample farmers received more profit before import restriction than after the restriction and they could not be able to cover their cost of black gram production after the restriction. The important reason for farmers receiving a larger profit before the restriction was that they got higher prices though total variable costs before the restriction was slightly higher than that of after restriction period. Thus, price is the significant factor for black gram production.

In profit regression estimates, effective price of black gram, sown area, age of household heads, hired labor cost and number of credit sources significantly influenced on profit of black gram production before import suspension. The same factors, except age of household heads, were significantly determined in concerning with the profit of black gram production after import suspension. In addition, access to extension service positively and significantly influenced on profit after import suspension. Thus, extension service is becoming an important factor because it can improve knowledge and information of other economically crops substitution among farmers. Moreover, credit sources are important for profitability of black gram farmers, access to more credit from different sources should be facilitated.

India is the large country importer of black gram and has more bargaining power to control the black gram market. Therefore, government and related institutions need to find out alternative international markets. To penetrate other international markets, quality and standard of black gram are becoming critical factors for farmers. Thus, farmers should be encouraged to produce quality product and extension services are required to provide improved agricultural practices. Moreover, trade agreement would be needed to compensate the risk of domestic farmers and traders.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture. (2017). Annual Pulses Production Report. Nay Pyi Taw. Myanmar.

Department of Agriculture. (2018). Annual Pulses Production Report. Nay Pyi Taw. Myanmar.

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. (2018). Myanmar Agriculture in Brief, Department of Planning. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

Thit, M. (2017, August 24). India’s policy change on pea imports impacts Myanmar. Retrieved from https://www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com/indias-policy-change-on-pea-impo...

|

Date submitted: November 15, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: December 9, 2019

|

Factors Influencing Profitability of Black Gram Production before and after India’s Import Suspension in Kyauktaga Township, Bago Region

ABSTRACT

Black gram is an economically important pulse in Myanmar and mainly exported to India. In August 2017, India announced a 200,000 tons import quota on pigeon peas and 150,000 tons quota each for black gram and green gram. This study aimed to analyze the determinants on profitability of black gram production before and after India’s import suspension. Total 120 sample farm households were chosen by using a simple random sampling method from six villages in Kyauktaga Township. Descriptive, cost and return, and regression analyses were employed. The findings indicated that after import suspension, the effective price of black gram was significantly decreased and benefit-cost ratio before import suspension was about double than after import suspension. Effective price of black gram, sown area, age of household heads, hired labor cost and numbers of credit sources were significantly influenced on profit of black gram production before import suspension. The same factors, except age of household heads, significantly determined the profit of black gram production after import suspension. In addition, access to extension service was positively and significantly influenced on profit after import suspension. Thus, research and extension services should pay attention to improve knowledge and information of alternative crops substitution. Because credit sources are important for profitability of black gram farmers, access to more credits from different sources should be facilitated.

Key words: black gram, before and after India’s import suspension, Bago Region, Myanmar.

INTRODUCTION

Pulses are attractive to farmers because they have lower production costs and better returns in comparison with other crops in Myanmar. Pulses contribute the major export portion among Myanmar’s agricultural export products. Major exportable pulses are black gram, green gram, pigeon pea, chickpea, soybean, butter bean, cowpea and kidney bean (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation [MOALI], 2018). Black gram, green gram and pigeon pea accounted for 70% of total pulses production. About 91% of total pigeon pea production and 77% of total black gram are exported to India and the domestic wholesale prices depend almost entirely on India’s demand (Department of Agriculture [DOA], 2017). Another exported pulse, green gram is exported to many countries including India, China, Indonesia, Malaysia and UAE.

Black gram (Vigna mungo) is the second largest cultivated pulse crop in Myanmar. It is cultivated in both monsoon and winter seasons and mainly planted after monsoon paddy on residual moisture. Bago Region is the largest cultivated area and production, followed by Ayeyawady and Sagaing Regions in 2017-2018 (DOA, 2018). In August 2017, India announced a 200,000 tons import quota on pigeon peas and 150,000 tons quota each for black gram and green gram. That time was two months before harvesting of the pigeon peas, and before planting time of black gram and green gram in Myanmar. India’s import restrictions which limited the amount of pea products from Myanmar have quickly and adversely affected the local pulses market in Myanmar (Thit, 2017). Therefore, this study was conducted to know how much the profit has been changed and the determining factors on the profitability of black gram production before and after India’s pulse import suspension.

Research methodology

Kyauktaga Township was chosen as the study area because of the largest cultivated area of black gram in Bago Region during 2016-2017 (DOA, 2017). Both primary and secondary data were used in this study. The primary information was collected from 120 sample farmers of six villages by personal interview with a structured questionnaire using simple random sampling method. The survey was conducted in January, 2019 after India’s import suspension in August, 2017. Descriptive statistics, cost and return analysis, and regression analysis were used with Microsoft excel and STATA 12 statistical software to fulfill the research objectives.

To determine the factors affecting profit of black gram production before and after import suspension in the study area, linear regression function was used. The regression function was as follows;

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic characteristics of sample farm households

Demographic characteristics of sample farm households were described in Table 1. The average age of household heads was 49 years within a range of 26 to 74 years. Farmers had 25 years of farming experience on average ranging from a minimum of 3 years to a maximum of 55 years. As the educational status, the average schooling years of farmers was middle school level (6 years). The maximum schooling years were 15 and the minimum was 1. The average family size of the sample farm households was 4. The maximum number of family members was 9 and minimum was one person. The average agricultural family labor of sample households was 1 within the range of no agricultural family labor to maximum 5 agricultural family labors.

Access to agricultural extension services before and after import suspension

Sample farmers received information related to black gram production practices from different sources such as private agro-input company and DOA. Table 2 presented that the sample households’ meeting attendance offered by private agro-input company and DOA. Before the restriction, about 20.83% and 50.00% of farmers had no contact with private and government extension agents. The attendance of extension training or meeting of farm households offered by private company and DOA was 8.33% and 25.00% for one time, 46.67% and 22.50% for two to three times and 20.00% and 2.50% for four to five times respectively. About 4.17% of farmers attended the meeting above five times by private company per season.

After the restriction, about 20.83% and 47.50 % of farm households had no contact with private and DOA extension agents. About 7.50% and 25.83% of farmers participated only one time in the agricultural extension meeting by private and government organizations. The attendance of extension meeting accessible by private company and DOA was 45.84% and 23.33% for two to three times and 20.83% and 3.34% for four to five times respectively. The contact time to extension agents above five times had 5.00% by private company.

Sources of credit taken by sample farm households before and after import suspension

According to survey data, MADB was the main credit source and about 36.68% of sample farm households received credit only from MADB as well as about 2.49% of sample farm households received from cooperative, Mya Sein Yaung (Evergreen project) and money lenders before the restriction (Table 3). About 20.83% of sample farm households received credit from two sources (MADB and money lenders), followed by MADB and cooperative, and MADB and Mya Sein Yaung before the restriction. About 10.00% of farmers received credit from three sources and about 1.67% of farmers received from four sources while about 2.50% of sample farm households did not take the credit before the restriction.

After the restriction, about 35.00% of sample farm households received credit from MADB and about 2.49% of sample farm households received credit from cooperative, Mya Sein Yaung and money lenders. About 20.83% of sample farm households received from MADB and money lenders, followed by MADB and cooperative, and MADB and Mya Sein Yaung. The percentage of sample farm households received credit from cooperative and money lenders, and Mya Sein Yaung and money lenders were not different after the restriction. About 13.33% of farmers received credit from three sources and the percentage of farmers received from four sources was not changed while only 1.67% of sample farm households did not take the credit after the restriction.

Changes in cultivated area and gross annual crop incomes by sample farm households before and after import suspension

Changes in cultivated areas by sample farm households before and after import suspension were shown in Table 4. According to results, all sample farmers cultivated monsoon rice and their cultivated areas were not significantly different before and after suspension. The number of black gram farmers decreased from 120 to 111 farmers and cultivated areas of black gram were significantly decreased from 3.17 ha to 2.66 ha at 10% level before and after suspension. The number of farmers cultivated green gram, cowpea and sesame crops increased but the number of farmers grown groundnut and other pulses (pae ni lay) were the same. The cultivated areas of green gram were significantly increased from 0.59 ha to 1.12 ha at 1% level after import suspension and that of groundnut, cowpeas, sesame and other pulses were not significantly different as compared to before and after import suspension. Thus, green gram was cultivated increasingly instead of black gram after import restriction.

Gross annual incomes of cultivated crops by sample farm households before and after import suspension were presented in Table 5. Monsoon rice was the main income source and the average amount of monsoon rice income increased from 3.22 to 3.52 million MMK per year before and after import suspension. Average black gram income was significantly decreased from 2.66 to 1.00 million MMK per year at 5% level before and after import suspension. Other crop incomes received from green gram, groundnut, cowpea, sesame and other pulses were increased but not significantly different before and after import suspension.

Black gram production of sample farm households before and after import suspension

According to survey results, sample farm households cultivated about an average of 3.17 ha of black gram before import suspension and decreased to 2.88 ha after import suspension (Table 6). Mean yield was decreased from 923.16 kg/ha to 885.49 kg/ha after import suspension. There were no significant differences in cultivated areas and yield between two years. Average total production of black gram was significantly decreased from 2,825.23 kg to 2,397.31 kg at 10% level after import suspension. Market price of black gram was decreased from 919 MMK/kg to 467 MMK/kg and it was significantly different at 5% level before and after import suspension.

Cost and return analysis of black gram production before and after import suspension

The enterprise budget was used to compare cost and return of black gram production before and after import suspension. Various measures of costs and returns were reported in Table 7. Effective black gram yield of sample farmers (851.69 kg/ha) before the restriction was slightly higher than that of sample farmers (811.23 kg/ha) after the restriction. Effective price of black gram (911.48 MMK/kg) before the restriction was also significantly higher than (461.35 MMK/kg) after the restriction. Therefore, average gross benefit before the restriction (776,296 MMK/ha) was significantly greater than after the restriction (374,260 MMK/ha). There were significantly different in price and gross benefit of black gram at 5% level before and after import suspension.

Total material cost included farmers’ owned materials such as seed and FYM, and bought materials such as seed, urea, compound, foliar fertilizer, herbicide, fungicide and insecticide. Costs for farmers’ owned materials were 68,536 MMK/ha and 64,769 MMK/ha respectively before and after import suspension. Material costs expended by farmers were 133,940 MMK/ha before import suspension and 131,427 MMK/ha after import suspension. Average total family labor cost were 136,747 MMK/ha and 139,443 MMK/ha before and after import suspension. It was expensed for hired labor cost of 228,712 MMK/ha and 223,812 MMK/ha respectively before and after the restriction. In the total interest cost on cash cost, farm households expended 29,012 MMK/ha and 28,419 MMK/ha respectively before and after import suspension. The total variable costs were 596,947 MMK/ha and 587,870 MMK/ha respectively before and after import suspension. There were not significantly different in all variable costs while comparing before and after import suspension.

Return above variable cost (RAVC) before the restriction was 179,349 MMK/ha and (-) 213,610 MMK/ha after the restriction. Hence, the benefit-cost ratios (BCRs) were 1.30 and 0.64 respectively before and after import suspension. They were significantly different in benefit-cost ratios at 5% level before and after import suspension. Therefore, it can be concluded that sample farm households received more profit before import restriction. The important reason for farmers receiving a larger profit before the restriction was that they got higher prices though total variable costs before the restriction was slightly higher than that of after restriction period.

Break-even yield for black gram production were 654.92 kg/ha and 1,274.24 kg/ha whereas break-even price were 700.90 MMK/kg and 724.67 MMK/kg respectively before and after import suspension. It was significantly different in break-even yield for black gram production at 1% level before and after import suspension.

Factors affecting the profitability of black gram production before and after import suspension

Black gram profit regression estimates before and after import suspension was described in Table 8. According to results before import suspension, the significant influencing factors of black gram profit were effective price of black gram, sown area of black gram, age of household heads, hired labor cost and number of credit sources. Black gram profit was positively correlated with effective price of black gram and number of credit sources at 1% level. It means that if price of black gram 1 MMK increased, black gram profit would be increased by 1,230 MMK per hectare and if the credit received by sample farmers in black gram production one source increased, black gram profit would be increased by 122,180 MMK per hectare. The result showed that if farmers received higher price, they would pay more attention in black gram production to get high income so price directly effects on profit and the government would be provided credit program to the farmers in black gram production. Black gram profit was negatively correlated with sown area of black gram at 5% level, age of household heads at 10% level and hired labor cost at 10% level respectively. If farmers cultivated black gram one hectare increased, the profit would be decreased by 25,220 MMK per hectare. The result showed that if cultivated area of black gram was increased, farmers would pay a lesser attention on management of black gram production. If farmers’ age one year older, they did not follow the technology in black gram production and therefore, profit will be decreased by 5,230 MMK per hectare. If hired labor cost of 1,000 MMK increased in black gram production in the study area, black gram profit would be decreased by 790 MMK per hectare. The result showed that the farmers who had suffered high cost of hired labor on the farm in black gram production could receive low profit. The adjusted R squared points out that the model is significant and it can explain the variation in black gram profit by 63 percent.

After import suspension, the same factors and the same trend except age of household heads were significantly determined the profit of black gram production at 1% level. In addition, access to extension service was also positively influenced on profit of black gram production at 5% level. If price of black gram 1 MMK increased, black gram profit would be increased by 490 MMK per hectare and if the credit received by sample farmers in black gram production one source increased, black gram profit would be increased by 61,440 MMK per hectare. If farmers cultivated black gram one hectare increased, the profit would be decreased by 18,960 MMK per hectare. If hired labor cost of 1,000 MMK increased in black gram production in the study area, black gram profit would be decreased by 940 MMK per hectare. This dummy variable, access to extension services (yes=1, no=0) specified that profit of black gram production by sample farmers who had received extension services was 91,090 MMK more than that farmers who did not receive extension services. Therefore, extension service is becoming much important for farmers after risk due to import suspension. The adjusted R squared points out that the model is significant and it can explain the variation in black gram profit by 33%.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

According to result findings, farmers had productive experiences and better potential for decision making in black gram production because they spent half of their lives in farming. Although they had many experiences in farming, India’s import suspension had negative effects on black gram farmers. Low demand from India by import suspension was a pulled factor for lower price in black gram domestic market. The cultivated areas decreased in black gram and increased in green gram significantly in the study area. Some farmers tried to solve by substituting green gram instead of black gram because green gram was exported to many other countries. Although MOALI recommended sunflower cultivation to sufficient domestic oil consumption, sample farmers have not yet cultivated sunflower in the study area. In the study area, there were very few economically alternative substitute crops and therefore, research and development are required for alternative crop substitution.

According to BCRs result, sample farmers received more profit before import restriction than after the restriction and they could not be able to cover their cost of black gram production after the restriction. The important reason for farmers receiving a larger profit before the restriction was that they got higher prices though total variable costs before the restriction was slightly higher than that of after restriction period. Thus, price is the significant factor for black gram production.

In profit regression estimates, effective price of black gram, sown area, age of household heads, hired labor cost and number of credit sources significantly influenced on profit of black gram production before import suspension. The same factors, except age of household heads, were significantly determined in concerning with the profit of black gram production after import suspension. In addition, access to extension service positively and significantly influenced on profit after import suspension. Thus, extension service is becoming an important factor because it can improve knowledge and information of other economically crops substitution among farmers. Moreover, credit sources are important for profitability of black gram farmers, access to more credit from different sources should be facilitated.

India is the large country importer of black gram and has more bargaining power to control the black gram market. Therefore, government and related institutions need to find out alternative international markets. To penetrate other international markets, quality and standard of black gram are becoming critical factors for farmers. Thus, farmers should be encouraged to produce quality product and extension services are required to provide improved agricultural practices. Moreover, trade agreement would be needed to compensate the risk of domestic farmers and traders.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture. (2017). Annual Pulses Production Report. Nay Pyi Taw. Myanmar.

Department of Agriculture. (2018). Annual Pulses Production Report. Nay Pyi Taw. Myanmar.

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. (2018). Myanmar Agriculture in Brief, Department of Planning. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

Thit, M. (2017, August 24). India’s policy change on pea imports impacts Myanmar. Retrieved from https://www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com/indias-policy-change-on-pea-impo...

Date submitted: November 15, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: December 9, 2019