ABSTRACT

The Thai government releaseed the national strategic plan in 2018, which grounds a 20-year roadmap for the country. However, this move did not overlook farmers in many aspects since the farmers have yet to perceive the usefulness of using technology in their lifestyle. The technologies i.e. smartphone, tablet, laptop or desktop computer were still perceived as learning technologies for their children. The farmers might perceive that the responsibility to adopt technology in their farms belongs to the next generation who are their children. Apart from digital literacy, Thai farmers also lack finiancial discipline since the majority of farmers perceive farming as an occupation rather than agribusiness. Thai farmers are able to change, adapt and learn when they see opportunities to survive in the world competitive market. However, government units still play an important role in the agro-industry since agribusiness requires support i.e. funding, technology, collaborations from the government. This emphasizes full collaborations among all stakeholders. This article discusses various perspectives to gain stakeholders’ understanding and enable to help farmers become ready for the digital age.

Keywords: Acceptance, Readiness, Digital Farming, Digital Techology

Introduction

According to the national 20-year strategy, there is an improvement plan for digital and technological infrastructure (NESDB, 2018). This plan aims to enhance farmers’ potential to be ready for market competition (InformationOperation, 2018). Moreover, it is promising to increase revenue and offer well-being for farmers. This also means getting rid of inequality in Thai society. To achive this goal, the farmers should significantly improve their productivity in both quantitative and value aspects. For instance, farming should consider promoting local identity and safety awareness and applying biotechnology, processing agriculture and smart IoT (Internet of Things) technology. To support farmers, the ministry of agriculture and cooperative recently released a 5-year digital agriculture plan (2017-2021), which includes a number of projects i.e. digital knowledge warehouse, one-stop-service information center, digital agriculture market system and backward tracable system for agricultural products.

From the national strategy, the policy for agriculture is to improve the quality of living for low-income farmers by increasing their revenue, creating sustainable farming and co-friendly, adopting and exploiting technologies and innovation to produce agricultural products and transforming farmers’ perspectives from simple individual occupation to agribusiness. To facilitate this transformation, it depends on adaptation of farmers in terms of knowledge and skills. Learning about tools, technology and innovation is an important step to make farmers ready for the new era of digital farming. This shows the need for strategies and tactics from the government to steer forward the development of agriculture and also the farmers, which will strengthen agribusiness and farmers to be able to survive in the rapidly dynamic market. The farmers in the Thai farming industry can be categorized into two groups. The former, majority of farmers, consider farming as an occupation. The latter consider themselves as businessmen. These two different mindsets result in a wide gap of potential in Thai agribusiness since they have different capabilities when responding to government’s strategies.

STAKEHOLDERS’ INVOLVEMENT AND COLLABORATioN

Recently, some farmers adopt the digital technology for transferring knowledge, concept and method of agriculture and farming via digital channels such as Facebook, Line App and YouTube. “Young Smart Farmers” is an example of a group, which applied digital technology in farming and also published their know-how via social media (Kehakaset, 2019). However, fake news is one of the problems in this digital era. When farmers receive wrong information from fake news, it can lead to the situation that is difficult to make or convince them to change their perception and behavior. For example, there is a belief that burning the harvested crops could help in improving nutrition in soils. This practice causes the mass pollution in Thailand. Fake news can cause widespread of misinformation and it is very difficult to make farmers to unlearn from what they have already believed.

The manager of the creative business centre of agricultural innovation also points out the relevance of adaptation of farmers. Also, technology adoption should consider area constraints, investments and eco-friendly atmosphere. There is a policy to promote smart farming by adopting technology, machine and innovation to improve accuracy in farm management, “precision farming” or “precision agriculture” concepts. At the beginning, precision farming was applied in small-area farming due to limitations of each individual plant’s requirements (BrandInside, 2016). It is mandatory to consider factors i.e. species, quality of soil, humidity, sunshine and weed, which are critical for farming. This policy brings about an awareness of small-area farmers. However, most famers fail to adapt themselves to become smart farmers as their technologies and behavior are quite far behind. For example, there is still a lack of access to the information for making decision and mitigating risks. To provide an integrated solution for farmers, there is a need for collaboration of stakeholders, especially among the government units.

However, there are a number of farmers who successfully adopt digital technology. For example, the “Young Smart Farmers” is a group of farmers who are willing to share their knowledge and experiences via internet channels i.e. Facebook, Line App and You Tube. This group as early adopters would possible help influencing and changing mindset of the majority of Thai farmers as slower adopters (Rogers, 2003). Other government units i.e. National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) and National Electronics and Computer Technology Centre (NECTEC) are the main government organizations, which are in charge of investing in research to support farming. Some of their projects release apps to provide relevant information such as weather forecast, farming in neighbor area etc., which helps farmers create a proper plan. NSTDA and NECTEC provide hardware technologies (equipment and machines) for collecting weather information and offer analysis service to farmers. This results in more accuracy of plant planning. The next step is to expand the applications of digital technology not just only for accuracy but also for serving area-based needs, fitting with business goal (profit and return on investments) and being eco-friendly. To achieve this, it needs huge investments from both government and farmers. This emphasizes that financial constraint is one of the major obstacles. Other problems are inequality of information access to government services. The policy should be amended to offer financial support, R&D to help farmers reduce the cost of farming.

Another example of collaboration between government units and private sector to support smart farming is the signing of a memo of understanding (MOU) between the ministry of digital for ecomomy and society (DE) and Total Access Communication PLC (DTAC – one of TelCo in Thailand). DE supports the establishment of digital infrastructure covering every district in the country, which aligns with the government policy to promote the use of digital technology. The aim is to strengthen the grass roots economy in Thailand and toprovide another opportunity and additional channel for farming community and consumer to meet each other. DTAC develops an application, Farmer Info app to provide up-to-date information on prices of agricultural products i.e. rice, vegetables, fruits, flowers, livestock, aquatic animals, economical plants and other agricultural products. The information consists of buying price for agricultural products at the relevant markets, retailed price at the fresh market in Bangkok (beneficial to consumer), costing information, basic farm production information, news in agri-industry, materials and equipment for agriculture, knowledgable video clips, and examples of role model farmers. Inevitably, Farmer Info app offers benefits to farmers and agribusiness entrepreneurs. Although Farmer Info app was downloaded over 50,000 times, usage is still considered low since it is restricted to be used within only DTAC network.

THE CHALLENGES IN CURRENT SITUATION

Government investment projects

The Thai government spends huge efforts to establish big data systems. The aim of these systems is to support forecasting, predicting and estimating market situations for farmers since the production of agricultural products mainly relies on natural conditions i.e. weather, soil condition, sunshine diseases and pests. Having this information in realtime will help farmers make decisions and respond to the market accurately on time (Wolfert et al, 2017). According to the benefits of applying information technology in farm production and marketing, many apps developed by government units are continuously released to the market with the purpose of helping farmers i.e. AgriMap Mobile, Protect Plants, Digital Farmer, OAE Ag-info, Rice Production Technology WMSC etc. Accordingly, there are also apps developed by universities and tech-startup companies. Sayruamyat and Nadee (2019) conducted a survey research with farmers and found that Thai farmers are less likely to be aware and to perceive the availability of mobile apps in the market. Despite this huge effort from many parties to help farmers gaining access to the information and increasing perception of the benefits when using information technology for decision making in farm management, the number of mobile apps in the market causes choice overload problem. This problem was raised by the study of Iyengar and Lepper (2000), which found that too many choices do not increase consumer’s motivation. Rather, it causes consumer frustration. The choice overload situation causes consumers to make decisions via satisfying heuristics in contrast to optimizing heuristic approaches, while limiting the number of choices. Choice overload is also time consuming. Although spending a long time in decision making does not matter in agricultural context as farmers do not rush to do things, it still causes negative perception to use and adopt mobile apps. According to Sayruamyat and Nadee (2019), it is found that most mobile apps released by many parties have yet to be in the attention of farmers. This study found that Thai farmers who are 50-year-old on average, are willing to accept the technology, which they are not familiar with. However, those farmers did not perceive the usefulness of the technology for their generation but are leaving the responsibility to their children. They end up using only social media app i.e. Line, Facebook and YouTube. Only the farmers who think forward, take the adoption of technology into their accounts.

Challenges in technology adoption

First, technologicial infrastructure is not ready or compatible with adopting digital technology. For example, there is a case at the learning centre of new farming theory at Thong Hatai, Cha-Am, Petchaburi. They tested an automatic watering system, controlled via mobile app and they found that the household electricity was not compatible with the requirement of the automatic watering system. The household electricity did not sufficiently supply power to the watering system (Techsauce, 2019). This indicates that technology or innovation adoption requires suitable infrastructures, which also needs subject matter experts to involve in the adoption process.

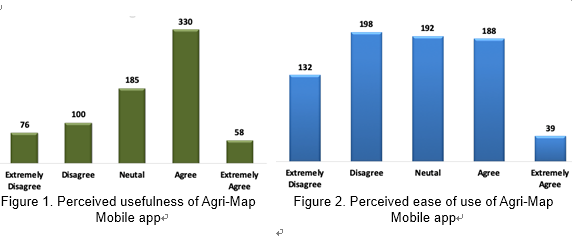

Second, the difficulty of using technology is one of the obstacles. In the agricultural society, there are mixed generations, who live different lifestyles and mindsets. This emphasizes the significant gap between the current state of farmers and the ideal farmer 4.0 (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). In the development of the apps for farmers, developers should consider user interface (UI) and user experiences (UX) to be friendly with mixed generations of farmers since most software developers these days are new generation who might not understand the perspective of the people from the old generation. Furthermore, most mobile apps have been developed for serving the aspects of large and medium scale of businesses. This possibly neglects the aspect of small communities. For example. Agri-Map Mobile app has been released to the targeted farmers who are in the old generation. They perceived the usefulness of the application but did not perceive the ease of use of the application as shown in figures 1 and 2.

Third, agricultural process requires end-to-end integration. The process starts from planting, nurturing, harvesting and transforming the products. However, the digital technology i.e. apps, machine or equipment available in the market is not developed with the consideration of integration with other technologies. This responsibility was left to the farmers. Some of them might obtain support from researchers or developers in the academia to customize technologies for integrating purposes. In contrast, large agricultural enterprises might have an advantage of research and development for integration of technology in terms of capital investments.

Fourth, there are additional costs for using and adopting digital technology i.e. internet charge, mobile network charge etc. These costs were automatically added to the farm management cost. As mentioned earlier, most Thai farmers are considered as family farming and not business farming entities. The perspective to cost management is different. For example, they do not separate household expenses from the expenses in farming. Farmers possibly refuse to use or adopt technologies since they realize the additional costs, which they need to pay.

Last, the majority of farmers do not posess smartphones or tablets. This situation is not because the farmers are unable to afford the technologies, but they do not see the necessity of occupying any smartphone or tablet according to their traditional lifestyles or their occupations as farmers. This is far beyond the problem of digital divide (Rogers, 2003) or inequality in the society. Rather, it is all about mindset of people generation.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Although the principle of the national 20-year strategic plan is designed to support all aspect (NESDB, 2018). However, the dynamic of digital technology is continuously and rapidly changing as we can say that there are disruptions occurring all the time in this industry. This shows the weak point of the national strategic plan, which aims at the long-term goal whlist, the disruptions might cause the plan invalid within a short-term period. Peter F. Drucker, the legend in management science, said that a good plan should be clear and logical but should not aim longer than 18 months (Drucker, 2008). Accordingly, Thai farmers gradually adapt themselves towards using technologies (Rambo, 2017). The government should amend the plan to be more specific with the expected outcomes, the approaches and the the clear purposes within 18 months.

The government units also need to create an additional policy to support building facilitating environments. These settings will drive behavioral change i.e. possessing a smartphone or a tablet to support the current attitude of farmers, who have already accepted digital technology. To eliminate the limitation and minimize costs, there is a need of support from the government. However, it should not be in a form of monetary subsidy as a country wide project. The support should be rolled out with pilot farmers who have the potential and are willing to participate and invest in their efforts. This will create a cycle of learning and knowledge transfer among farmers. In traditional Thai society, social norm has high impact in behavior change including the agricultural context. Recently, there is an increasing number of durian production areas according to the demand of consumption in China and the incoming flow of investments in durian farming from China and Vietnam. This reflects that Thai farmers are willing to adapt and change to take challenges if there is an opportunity. However, choosing potential pilot groups are significant to motivate other large groups of farmers to learn and adopt digital technology. Government policies should include supporting role models to become influencers (Hennessy, 2018) in agricultural industry, which will be another force to drive farmers towards digital technology adoption.

In addition, there are still inequality and creditability problems in accessing relevant information from data owned by government units. This causes farmers not to trust the use of data from government although the data might be useful in farm managment i.e. weather forecast, production, price. The main problems are that the data is not regularly updated, not integrated with other relevant government units and not consistent. These problems cause farmers to produce following their own heuristic decisions. Therefore, the farmers should not be the only party to be blamed for not using or adopting technology.

Lastly, there are huge numbers of unreliable information i.e. fake news, biased opnions distributed in social media. Even Facebook, which owns the biggest social media platform also accept that there are too many fake news posted on their site everyday. Facebook also spends a lot of resources and efforts to deal with these problems seriously. This also leaves social media readers to carefully consider the information themselves. If farmers receive misled information, it will be difficult for the responsible party to correct the damage. An example of actions from the government could be to establish a PR team to proactively deal with the issue of fake news or misleading information on social media via simple techniques such as using infographics to communicate with farmers.

REFERENCES

BrandInside. 2016. Smart Farming – Hope and opportunity of Thailand (https://brandinside.asia/smart-farming-thailand-opportunity/; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Drucker, P.F. 2008. Managing Oneself, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA.

Hennessy, B. 2018. Influencer: Building Your Personal Brand in the Age of Social Media, New York: Citadel Press.

InformationOperation. 2018. What is Thailand’s 20-Year National Strategy? (https://www.io-pr.org/051061-3/; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Iyengar, S. S. and Lepper, M. R. 2000. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of personality and social psychology, 79, p.995.

Kehakaset. 2019. How does Thai agriculture step in the digital age? (https://www.kehakaset.com/articles_details.php?view_item=776; Accessed 21 April 2019).

NESDB. 2018. National Strategy (https://www.nesdb.go.th/download/document/SAC/NS_SumPlanOct2018.pdf; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Rambo, A.T. 2017. From poor peasants to entrepreneurial farmers: the transformation of rural life in Northeast Thailand, Honolulu, HI: East-West Center, (https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/48535; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Rogers, E.M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations, New York: Free Press.

Sayruamyat, S. and Nadee, W. 2019. Acceptance and Readiness of Thai Farmers toward Digital Technology. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart Trends for Computing and Communications (SmartCom 2019), 24 - 25 January 2019, Bangkok, Thailand.

Techsauce. 2019. Unreal dream of smart farming, intelligent agriculture at the community level (https://techsauce.co/saucy-thoughts/the-challenge-of-smart-farming-in-thailand/; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F.D., 2000. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Management science, 46:2, p.186.

Wolfert, S., Ge, L., Verdouw, C. and Bogaardt, M.-J. 2017. Big data in smart farming–a review. Agricultural Systems, 153, pp.69-80.

|

Date submitted: May. 14, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: June. 13, 2019

|

Acceptance and Readiness of Thai Farmers toward Digital Technology

ABSTRACT

The Thai government releaseed the national strategic plan in 2018, which grounds a 20-year roadmap for the country. However, this move did not overlook farmers in many aspects since the farmers have yet to perceive the usefulness of using technology in their lifestyle. The technologies i.e. smartphone, tablet, laptop or desktop computer were still perceived as learning technologies for their children. The farmers might perceive that the responsibility to adopt technology in their farms belongs to the next generation who are their children. Apart from digital literacy, Thai farmers also lack finiancial discipline since the majority of farmers perceive farming as an occupation rather than agribusiness. Thai farmers are able to change, adapt and learn when they see opportunities to survive in the world competitive market. However, government units still play an important role in the agro-industry since agribusiness requires support i.e. funding, technology, collaborations from the government. This emphasizes full collaborations among all stakeholders. This article discusses various perspectives to gain stakeholders’ understanding and enable to help farmers become ready for the digital age.

Keywords: Acceptance, Readiness, Digital Farming, Digital Techology

Introduction

According to the national 20-year strategy, there is an improvement plan for digital and technological infrastructure (NESDB, 2018). This plan aims to enhance farmers’ potential to be ready for market competition (InformationOperation, 2018). Moreover, it is promising to increase revenue and offer well-being for farmers. This also means getting rid of inequality in Thai society. To achive this goal, the farmers should significantly improve their productivity in both quantitative and value aspects. For instance, farming should consider promoting local identity and safety awareness and applying biotechnology, processing agriculture and smart IoT (Internet of Things) technology. To support farmers, the ministry of agriculture and cooperative recently released a 5-year digital agriculture plan (2017-2021), which includes a number of projects i.e. digital knowledge warehouse, one-stop-service information center, digital agriculture market system and backward tracable system for agricultural products.

From the national strategy, the policy for agriculture is to improve the quality of living for low-income farmers by increasing their revenue, creating sustainable farming and co-friendly, adopting and exploiting technologies and innovation to produce agricultural products and transforming farmers’ perspectives from simple individual occupation to agribusiness. To facilitate this transformation, it depends on adaptation of farmers in terms of knowledge and skills. Learning about tools, technology and innovation is an important step to make farmers ready for the new era of digital farming. This shows the need for strategies and tactics from the government to steer forward the development of agriculture and also the farmers, which will strengthen agribusiness and farmers to be able to survive in the rapidly dynamic market. The farmers in the Thai farming industry can be categorized into two groups. The former, majority of farmers, consider farming as an occupation. The latter consider themselves as businessmen. These two different mindsets result in a wide gap of potential in Thai agribusiness since they have different capabilities when responding to government’s strategies.

STAKEHOLDERS’ INVOLVEMENT AND COLLABORATioN

Recently, some farmers adopt the digital technology for transferring knowledge, concept and method of agriculture and farming via digital channels such as Facebook, Line App and YouTube. “Young Smart Farmers” is an example of a group, which applied digital technology in farming and also published their know-how via social media (Kehakaset, 2019). However, fake news is one of the problems in this digital era. When farmers receive wrong information from fake news, it can lead to the situation that is difficult to make or convince them to change their perception and behavior. For example, there is a belief that burning the harvested crops could help in improving nutrition in soils. This practice causes the mass pollution in Thailand. Fake news can cause widespread of misinformation and it is very difficult to make farmers to unlearn from what they have already believed.

The manager of the creative business centre of agricultural innovation also points out the relevance of adaptation of farmers. Also, technology adoption should consider area constraints, investments and eco-friendly atmosphere. There is a policy to promote smart farming by adopting technology, machine and innovation to improve accuracy in farm management, “precision farming” or “precision agriculture” concepts. At the beginning, precision farming was applied in small-area farming due to limitations of each individual plant’s requirements (BrandInside, 2016). It is mandatory to consider factors i.e. species, quality of soil, humidity, sunshine and weed, which are critical for farming. This policy brings about an awareness of small-area farmers. However, most famers fail to adapt themselves to become smart farmers as their technologies and behavior are quite far behind. For example, there is still a lack of access to the information for making decision and mitigating risks. To provide an integrated solution for farmers, there is a need for collaboration of stakeholders, especially among the government units.

However, there are a number of farmers who successfully adopt digital technology. For example, the “Young Smart Farmers” is a group of farmers who are willing to share their knowledge and experiences via internet channels i.e. Facebook, Line App and You Tube. This group as early adopters would possible help influencing and changing mindset of the majority of Thai farmers as slower adopters (Rogers, 2003). Other government units i.e. National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) and National Electronics and Computer Technology Centre (NECTEC) are the main government organizations, which are in charge of investing in research to support farming. Some of their projects release apps to provide relevant information such as weather forecast, farming in neighbor area etc., which helps farmers create a proper plan. NSTDA and NECTEC provide hardware technologies (equipment and machines) for collecting weather information and offer analysis service to farmers. This results in more accuracy of plant planning. The next step is to expand the applications of digital technology not just only for accuracy but also for serving area-based needs, fitting with business goal (profit and return on investments) and being eco-friendly. To achieve this, it needs huge investments from both government and farmers. This emphasizes that financial constraint is one of the major obstacles. Other problems are inequality of information access to government services. The policy should be amended to offer financial support, R&D to help farmers reduce the cost of farming.

Another example of collaboration between government units and private sector to support smart farming is the signing of a memo of understanding (MOU) between the ministry of digital for ecomomy and society (DE) and Total Access Communication PLC (DTAC – one of TelCo in Thailand). DE supports the establishment of digital infrastructure covering every district in the country, which aligns with the government policy to promote the use of digital technology. The aim is to strengthen the grass roots economy in Thailand and toprovide another opportunity and additional channel for farming community and consumer to meet each other. DTAC develops an application, Farmer Info app to provide up-to-date information on prices of agricultural products i.e. rice, vegetables, fruits, flowers, livestock, aquatic animals, economical plants and other agricultural products. The information consists of buying price for agricultural products at the relevant markets, retailed price at the fresh market in Bangkok (beneficial to consumer), costing information, basic farm production information, news in agri-industry, materials and equipment for agriculture, knowledgable video clips, and examples of role model farmers. Inevitably, Farmer Info app offers benefits to farmers and agribusiness entrepreneurs. Although Farmer Info app was downloaded over 50,000 times, usage is still considered low since it is restricted to be used within only DTAC network.

THE CHALLENGES IN CURRENT SITUATION

Government investment projects

The Thai government spends huge efforts to establish big data systems. The aim of these systems is to support forecasting, predicting and estimating market situations for farmers since the production of agricultural products mainly relies on natural conditions i.e. weather, soil condition, sunshine diseases and pests. Having this information in realtime will help farmers make decisions and respond to the market accurately on time (Wolfert et al, 2017). According to the benefits of applying information technology in farm production and marketing, many apps developed by government units are continuously released to the market with the purpose of helping farmers i.e. AgriMap Mobile, Protect Plants, Digital Farmer, OAE Ag-info, Rice Production Technology WMSC etc. Accordingly, there are also apps developed by universities and tech-startup companies. Sayruamyat and Nadee (2019) conducted a survey research with farmers and found that Thai farmers are less likely to be aware and to perceive the availability of mobile apps in the market. Despite this huge effort from many parties to help farmers gaining access to the information and increasing perception of the benefits when using information technology for decision making in farm management, the number of mobile apps in the market causes choice overload problem. This problem was raised by the study of Iyengar and Lepper (2000), which found that too many choices do not increase consumer’s motivation. Rather, it causes consumer frustration. The choice overload situation causes consumers to make decisions via satisfying heuristics in contrast to optimizing heuristic approaches, while limiting the number of choices. Choice overload is also time consuming. Although spending a long time in decision making does not matter in agricultural context as farmers do not rush to do things, it still causes negative perception to use and adopt mobile apps. According to Sayruamyat and Nadee (2019), it is found that most mobile apps released by many parties have yet to be in the attention of farmers. This study found that Thai farmers who are 50-year-old on average, are willing to accept the technology, which they are not familiar with. However, those farmers did not perceive the usefulness of the technology for their generation but are leaving the responsibility to their children. They end up using only social media app i.e. Line, Facebook and YouTube. Only the farmers who think forward, take the adoption of technology into their accounts.

Challenges in technology adoption

First, technologicial infrastructure is not ready or compatible with adopting digital technology. For example, there is a case at the learning centre of new farming theory at Thong Hatai, Cha-Am, Petchaburi. They tested an automatic watering system, controlled via mobile app and they found that the household electricity was not compatible with the requirement of the automatic watering system. The household electricity did not sufficiently supply power to the watering system (Techsauce, 2019). This indicates that technology or innovation adoption requires suitable infrastructures, which also needs subject matter experts to involve in the adoption process.

Second, the difficulty of using technology is one of the obstacles. In the agricultural society, there are mixed generations, who live different lifestyles and mindsets. This emphasizes the significant gap between the current state of farmers and the ideal farmer 4.0 (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). In the development of the apps for farmers, developers should consider user interface (UI) and user experiences (UX) to be friendly with mixed generations of farmers since most software developers these days are new generation who might not understand the perspective of the people from the old generation. Furthermore, most mobile apps have been developed for serving the aspects of large and medium scale of businesses. This possibly neglects the aspect of small communities. For example. Agri-Map Mobile app has been released to the targeted farmers who are in the old generation. They perceived the usefulness of the application but did not perceive the ease of use of the application as shown in figures 1 and 2.

Third, agricultural process requires end-to-end integration. The process starts from planting, nurturing, harvesting and transforming the products. However, the digital technology i.e. apps, machine or equipment available in the market is not developed with the consideration of integration with other technologies. This responsibility was left to the farmers. Some of them might obtain support from researchers or developers in the academia to customize technologies for integrating purposes. In contrast, large agricultural enterprises might have an advantage of research and development for integration of technology in terms of capital investments.

Fourth, there are additional costs for using and adopting digital technology i.e. internet charge, mobile network charge etc. These costs were automatically added to the farm management cost. As mentioned earlier, most Thai farmers are considered as family farming and not business farming entities. The perspective to cost management is different. For example, they do not separate household expenses from the expenses in farming. Farmers possibly refuse to use or adopt technologies since they realize the additional costs, which they need to pay.

Last, the majority of farmers do not posess smartphones or tablets. This situation is not because the farmers are unable to afford the technologies, but they do not see the necessity of occupying any smartphone or tablet according to their traditional lifestyles or their occupations as farmers. This is far beyond the problem of digital divide (Rogers, 2003) or inequality in the society. Rather, it is all about mindset of people generation.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Although the principle of the national 20-year strategic plan is designed to support all aspect (NESDB, 2018). However, the dynamic of digital technology is continuously and rapidly changing as we can say that there are disruptions occurring all the time in this industry. This shows the weak point of the national strategic plan, which aims at the long-term goal whlist, the disruptions might cause the plan invalid within a short-term period. Peter F. Drucker, the legend in management science, said that a good plan should be clear and logical but should not aim longer than 18 months (Drucker, 2008). Accordingly, Thai farmers gradually adapt themselves towards using technologies (Rambo, 2017). The government should amend the plan to be more specific with the expected outcomes, the approaches and the the clear purposes within 18 months.

The government units also need to create an additional policy to support building facilitating environments. These settings will drive behavioral change i.e. possessing a smartphone or a tablet to support the current attitude of farmers, who have already accepted digital technology. To eliminate the limitation and minimize costs, there is a need of support from the government. However, it should not be in a form of monetary subsidy as a country wide project. The support should be rolled out with pilot farmers who have the potential and are willing to participate and invest in their efforts. This will create a cycle of learning and knowledge transfer among farmers. In traditional Thai society, social norm has high impact in behavior change including the agricultural context. Recently, there is an increasing number of durian production areas according to the demand of consumption in China and the incoming flow of investments in durian farming from China and Vietnam. This reflects that Thai farmers are willing to adapt and change to take challenges if there is an opportunity. However, choosing potential pilot groups are significant to motivate other large groups of farmers to learn and adopt digital technology. Government policies should include supporting role models to become influencers (Hennessy, 2018) in agricultural industry, which will be another force to drive farmers towards digital technology adoption.

In addition, there are still inequality and creditability problems in accessing relevant information from data owned by government units. This causes farmers not to trust the use of data from government although the data might be useful in farm managment i.e. weather forecast, production, price. The main problems are that the data is not regularly updated, not integrated with other relevant government units and not consistent. These problems cause farmers to produce following their own heuristic decisions. Therefore, the farmers should not be the only party to be blamed for not using or adopting technology.

Lastly, there are huge numbers of unreliable information i.e. fake news, biased opnions distributed in social media. Even Facebook, which owns the biggest social media platform also accept that there are too many fake news posted on their site everyday. Facebook also spends a lot of resources and efforts to deal with these problems seriously. This also leaves social media readers to carefully consider the information themselves. If farmers receive misled information, it will be difficult for the responsible party to correct the damage. An example of actions from the government could be to establish a PR team to proactively deal with the issue of fake news or misleading information on social media via simple techniques such as using infographics to communicate with farmers.

REFERENCES

BrandInside. 2016. Smart Farming – Hope and opportunity of Thailand (https://brandinside.asia/smart-farming-thailand-opportunity/; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Drucker, P.F. 2008. Managing Oneself, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA.

Hennessy, B. 2018. Influencer: Building Your Personal Brand in the Age of Social Media, New York: Citadel Press.

InformationOperation. 2018. What is Thailand’s 20-Year National Strategy? (https://www.io-pr.org/051061-3/; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Iyengar, S. S. and Lepper, M. R. 2000. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of personality and social psychology, 79, p.995.

Kehakaset. 2019. How does Thai agriculture step in the digital age? (https://www.kehakaset.com/articles_details.php?view_item=776; Accessed 21 April 2019).

NESDB. 2018. National Strategy (https://www.nesdb.go.th/download/document/SAC/NS_SumPlanOct2018.pdf; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Rambo, A.T. 2017. From poor peasants to entrepreneurial farmers: the transformation of rural life in Northeast Thailand, Honolulu, HI: East-West Center, (https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/48535; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Rogers, E.M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations, New York: Free Press.

Sayruamyat, S. and Nadee, W. 2019. Acceptance and Readiness of Thai Farmers toward Digital Technology. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart Trends for Computing and Communications (SmartCom 2019), 24 - 25 January 2019, Bangkok, Thailand.

Techsauce. 2019. Unreal dream of smart farming, intelligent agriculture at the community level (https://techsauce.co/saucy-thoughts/the-challenge-of-smart-farming-in-thailand/; Accessed 21 April 2019).

Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F.D., 2000. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Management science, 46:2, p.186.

Wolfert, S., Ge, L., Verdouw, C. and Bogaardt, M.-J. 2017. Big data in smart farming–a review. Agricultural Systems, 153, pp.69-80.

Date submitted: May. 14, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: June. 13, 2019