Introduction

The National Target Program (NTP) on developing New Rural Areas (NRA) in Vietnam was implemented in accordance with Decision 800/QĐ-TTg issued on 4 June, 2010 by the Prime Minister (hereinafter referred to as Decision 800). This program has an overall objective of “developing NRA with modern socio-economic infrastructure, appropriate economic and production structure, linking agriculture with quick development of industry and services; linking rural and urban development as planned; developing democratic, stable and rich cultural identity in rural areas; preserving the ecosystem; maintaining social order and security; and improving the physical and mental life of people in accordance with socialism orientation”. The specific objective of this program is that by 2015 20% of communes would meet NRA targets; and 50% of communes will meet NRA targets by 2020.

The development of NRA has encountered a number of difficulties and obstacles over the past years. The government, ministries and related bodies have issued a variety of supporting policies, yet none of the research has fully evaluated the application and impact of these policies to the development of NRA. Thus, an impact assessment study on these policies is essential to enable the government to consider the impact of issued policies, and timely make further adjustment to the policies if needed.

This study was carried out on a nationwide scope, focusing on localities participating in NRA pilot program in the period of industrialization and modernization acceleration. These provinces are those with communes that have taken part in NRA policies development at early stage. As a result, they offer the basis for analysis and comparison of policy impacts. Seven provinces were selected to represent socio-economic regions of the entire country for the survey. Commune is the grassroots level for developing NRA. Commune level is where the majority of projects or programs on NRA was undertaken, and NRA targets also take commune as grassroots level. Therefore, the spatial scope for impact assessment study is also inclusive of communal level, specifically, the impact of rural development on local beneficiaries. Information and data for the study are collected from 2009 when the NRA pilot program commenced until the end of 2013.

Summary of some NRA policies in Vietnam

NRA development targets

- The contents and activities must aim at implementing the 19 targets specified in the National Targets for NRA;

- Promote the hosting role of local residents in the community;

- Inherit and integrate national target programs and targeted support programs with other programs and projects being undertaken in the locality.

- Develop NRA in compliance with local socio-economic development plan with plans and mechanism to ensure the implementation of NRA planning;

- Apply public and transparent management and utilization of resources; strengthen decentralization, empowering commune authority in terms of administration and operations of works and projects;

- Developing NRA is the common task of the entire political and social system.

The development of NRA program contains 11 main contents, including:

- NRA development planning;

- Socio-economic infrastructure development;

- Restructuring, economic growth, and income improvement;

- Poverty reduction, and social security improvement;

- Reforming and development efficient production forms in rural areas;

- Rural education and training development;

- Health care development for rural residents;

- Development of cultural lifestyle, and rural information and communication;

- Provision of clean water and environmental sanitation in rural areas;

- Quality improvement in party, government and socio-political affairs at local level;

- Maintenance of social order and security in rural areas.

Supporting policies on NRA development

There are four primary sources of funding for NRA development. These include (i) state budget (inclusive of central and provincial state budget, which becomes direct funding for the program) (accounting for 40% of the total funding); (ii) credit (representing 30%); (iii) corporate investments (constituting 20%); and community contribution (occupying 10%).

Decision 800 and Decision 491 are two legal instruments setting out the orientation for NRA development; there are also a number of guidance issued by ministries providing support for each contents of NRA development. It is possible to divide these policies into two main groups as written below:

Direct support policies: include direct support for communes to execute the 19 targets of NRA. Relevant ministries and bodies preside over the proposal to the government for issuing specific regulations on investments and support.

Indirect support policies: include policies supporting the development of NRA, indirectly impact on the achievement of NRA targets; for example, policies on vocational training for rural labor, policies on bringing young intellectuals to rural areas; credit policies, policies encouraging enterprises to invest in rural areas and agriculture in general.

In this paper, I will focus on evaluating two important NRA policies, namely the policy on socio-economic infrastructure development, and the policy on vocational training for rural areas.

Impact Assessment of two NRA policies on rural infrastructure and labor training

Policy on socio-economic infrastructure development

Overview of policies

Socio-economic infrastructure development is the second in the 11 contents of NRA development. This content includes seven activities: (1) complete road traffic to commune people’s committee’s office (PC office) and road traffic within the commune; (2) Complete the electricity system to supply daily life and production needs in the commune; (3) Complete works serving the cultural and sports demand of the commune; (4) Complete works serving the standardization of health care in the commune; (5) Complete works serving the standardization of education; (6) Complete commune PC office and other auxiliary works; and (7) Renovate and construct new irrigation system in the commune.

Joint circular No. 26 issued by MARD, MPI and MOF provides detailed guidance on socio-economic infrastructure development. Particularly, Decision 800 also specifies that the State budget shall provide full (100%) funding for five works mentioned above. However, as of 8 June 2012, the Prime Minister issued Decision 695/QD-TTg to adjust the funding, in which only commune PC’s office would receive full funding, four other works would only receive partial funding in compliance with the decision of provincial people’s council, and the funding source was generally stated as state budget (including both central and local state budget).

In the implementation of this policy, localities set priority to spend various resources on infrastructure development, which is the primary factor to reform rural areas, creating momentum for socio-economic development, and benefiting local residents. A number of localities have actively issued flexible mechanism that fits their own particular conditions to mobilize resources for infrastructure investments.

In accordance with the regulations, the commune’s New rural area (NRA) project is developed and approved by district People Comitee (PC). Thereafter, detailed plan will be made by NRA development management board (MB) when each construction item for NRA is deployed.

New rural area (NRA) communes of central government have been deployed since 2009. As the very first pilot communes, they received significant funding from the state budget as well as other programs and projects. On the other hand, pilot provincial communes, having commenced since 2011, received less funding. As a result, only several small-scale works, renovation and refurbishment were invested in these communes.

In accordance with Decision 800, infrastructure works specified within the scope of this paper (including PC’s office, roads, health station and commune cultural and sports centers) receive full (100%) funding from state budget. Therefore, communal authorities did not mobilize funding from community. In fact, according to our field-study, the community did not financially contribute to these works.

As stipulated by regulations, the development priority must have community counseling. In our field-study, NRA development management board only counseled and received consensus from the commune people’s council, which has representatives of villages and relevant bodies. This way of conduct does not violate the regulations on democracy at the grassroots level. Circular 26 requires community counseling yet does not specify how to conduct such counseling. As a result, the management board only counseled the commune people’s council for infrastructure works that did not mobilize community financial contribution.

The majority of communes focused their funding on developing infrastructure, as this played as the face of the rural areas. Also, this development received full funding from the state budget, and it was relatively easy to execute. Meanwhile, capital needed for production was relatively lower. Households wished to receive more investments in works at villages.

The NRA development pilot appointed to the party secretariat in 11 communes ended at the end of 2011. However, till the beginning of 2013, a number of socio-economic infrastructure items in pilot communes were not finalized or were finalized yet not put into use. The reason for this fact is the lack of funding. Some communes allowed private corporate to advance their fund for the construction of these items and hoped that the state budget would be received later, or the commune PC would sell land (permitted) to pay back the advancement. However, due to the lack of funding or difficulty in sale of land, some communes accumulated large amount of private debt. For example, Thuy Huong commune (Chuong My District, Hanoi) owed more than VND 60 billion, or Hai Duong commune (Hai Hau District, Nam Dinh Province) had to suspend the completion of its office due to insufficient funding.

Another point to consider is that some communes had to mobilize various sources of funding for infrastructure works by integrating different resources. That disbursement and settlement mechanism of different funding sources vary, together with different technical norms, causes much complexity in the construction process.

All communes participated in the survey undertook the role of investors in all infrastructure development projects. At the beginning of the project, the commune authorities encountered a number of challenges when they had to handle a large number of documents and processes for each project. Meanwhile, the capacity of commune staff was limited; support had to be given from district authorities. After a while, commune officials became more familiar with the new process. However, to implement an infrastructure item from surveying, the designing is too complicated comparing to the building capacity of farmers.

Besides NRA pilot communes of the Party secretariat, other communes commenced NRA development in 2011. Due to low state budget allocation, particularly that from the central state budget, the primary activities in the early phase of infrastructure development included (i) finalizing management structure, (ii) communication, (iii) training and capacity building, (iv) NRA planning, and (v) developing NRA project.

The state budget was mainly allocated to the abovementioned activities, infrastructure development activities were initially implemented in some small projects. Infrastructure items were primarily works that received full state funding or combined funding. Some communes also deployed works at village level with the focus on village roads and village cultural center.

The survey reveals that communal authorities were active in communication and mobilization of resources for investments, thereby learning from the experiences of previously implemented communes. However, commune authorities often mentioned the following obstacles regarding socio-economic infrastructure development:

- Debt is quite common is capital construction at local level. Communes that immediately started on investing in infrastructure works but didn’t receive sufficient funding often owed the corporate organization. Even, incomplete works accompanied with debt existed in a number of communes.

- Compared with the standards set in the national NRA targets, the investment rate of infrastructure development at commune was relatively high, especially, in mountainous areas where people live scatterly in large areas of complicated landscape. The rate of investments in traffic road in such areas was quite large.

- Communal staff capacity was still limited at the early phase when they mostly concentrated on developing plan and project. It was still challenging to master the role of infrastructure development investors. The coordination between local bodies was incomprehensive and loose.

- Communes met obstacles on combining funds from various aid programs due to the lack of guiding documents. Thus, when starting to develop infrastructure, they had to go through numerous procedures depending on the aid programs.

- Direct state budget for NRA program was quite small. In 2012-2013, the amount of support from the central government allocated to provinces fell in the range from VND 30 billion to VND 100 billion per province. If such fund had been presumably allocated to all communes registering for NRA, each commune would have received from about VND 600 million to VND 2 billion by 2015. Such insignificant amount of funding cannot help communes invest in all infrastructure projects as specified in their communes’ NRA plan, particularly with communes outside the target program which received limited amount of combined funds for investment.

- The selection of targeted communes to fulfill 19 NRA criteria by 2015 resulted in the unbalanced allocation of investment resources. Provinces mainly focused their resources on targeted communes, which triggered dissatisfaction among residents and officials of other communes.

- Targets were met but remained unsustainable: after two years of NRA development, pilot communes reached outcomes satisfying all the targets of socio-economic infrastructure development, yet not at satisfactory level. Works were basically invested in to complete the building framework; meanwhile facility and equipment were outdated or left uninvested. With respect to pilot commune of provinces, some communes also met the medical targets, yet their health station quality did not satisfy the grading scale specified in the medical norms issued by MOH.

Results of implementing policy on socio-economic infrastructure development

- Regarding rural transport development: over 5,000 roads with approximately 70,000 km of rural roads have been constructed within three years in the whole nation. Almost 12% of the communes have met transport targets.

- Schools at all levels: In terms of schools, 198 new schools have been built; additional classrooms have been constructed to include 25,794; 39,480; and 5,018 classrooms for kindergarten, primary schools and senior high schools respectively. Almost 22% of the communes have met the school targets with 289 kindergartens, 1,910 preschools, 5,254 primary schools, and 2,164 secondary schools satisfying national standard.

- Health station system: 99.51% of communes have health stations, 72% of health stations have doctors, and over 95% of health stations have maternity wards. 45.9% of communes have met national medical standards.

- Cultural facility: 44.8% of communes have commune-level cultural and sport center. Almost 8% communes met cultural facility standards.

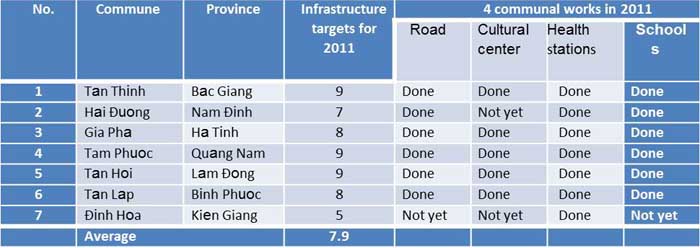

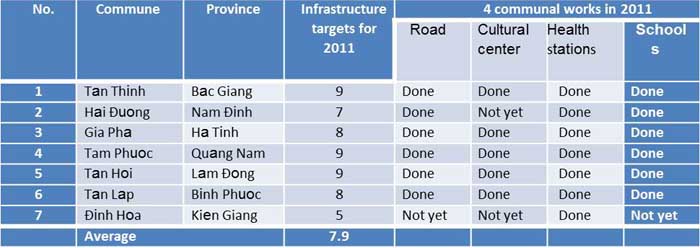

Table 1. Results achieved by 7 pilot communes

Source: IPSARD, 2015

Assessing the Impact of infrastructure development policy

The five commune socio-economic infrastructure items, including commune office, health stations, schools, roads and cultural centers, will have an impact on the entire commune community from individuals to organizations once they are constructed. In general, the residents view infrastructure works as beneficial to the production development and improving quality of life of the rural population. The survey results of 111 households in seven pilot communes show that most of the people evaluated the investments in infrastructure works created better conditions for life, production, medical examination at health stations, studying at commune schools, participation in cultural and sports activities, and environment protection.

Table 2. Residents’ assessment of 7 pilot communes in terms of infrastructure

Source: IPSARD, 2015

As of May 2014, 98.3% of communes had roads to commune centers, 87.4% of which were asphalt and concrete. Local authorities affirmed that better roads enabled better transport and trading. The construction of commune cultural and sports center in compliance with standards has facilitated the residents to enjoy cultural, sports and social events. 83.8% of interviewees agreed with this view. For example, in Tam Phuong commune (Phu Ninh district, Quang Nam province), the residents were particularly content with the center as they can hold weddings in this place where commune leadership would make announcement and present gifts in this event which makes them feel proud and lessens the concern of wedding organization.

According to the report of the Central Steering Committee (CSC) in 2014, about 78.8% of commune health stations experienced medical examination and treatment using health care insurance. The proportion of villages and hamlets having medical staff reached 86%. Health care at grassroots level saw much improvement by expanding medical services at the commune level, piloting the management of several chronic diseases, which lessens the pressure onto upper medical level. Seventy-three percent (73%) of residents claimed that medical examination and treatment in pilot communes had been improved.

Investments in improving educational infrastructure have created more favorable conditions for rural students, which was rated as ‘improved’ by 68.5% of local residents. According to the 2014 report of the CSC, the number of kindergarten-goers rose by 15.8% compared with the figure for 2008; children going to preschools also increased by 11.4% compared with the figure for 2008. The system of boarding schools for minority ethnic students has also been improved, receiving from 7-12% of ethnic students’ enrolment. The tuition fee support policy applicable to ethnic students as well as student loans are adjusted to facilitate rural students’ pursuing education.

Due to better transport, trading of goods is also improved. This, in turn, makes production better, contributing to income generation for rural residents. A three-year report of NRA development stated that the rural residents’ income in 2013 grew by 1.8% times compared with that of 2010. The proportion of poor rural households in 2013 stayed at 12.6%, representing an average drop of 2% pa. compared with that of 2008.

Some limitations and inadequacies of infrastructure development policies

- Funding for NRA infrastructure development often comes from various sources, each of which has different processing while there is no obvious guidance for the use of these sources; thus, local authorities encounters a number of difficulties in using these budgets.

- State budget allocated to infrastructure development in NRA is relatively low; therefore, local authorities only develop infrastructure in pilot communes, other communes receive very little investments in infrastructure.

- Budget is often poured in insufficiently and slowly, which delays the development for years.

Policy on vocational training for rural labor

Overview of policies

Contents relevant to policies vocational training for rural labor (hereinafter referred to as Project 1956) are specified in Decision 1956/QD-TTg issued on 27 November 2009, and Joint Circular 112/2010/TTLT-BTC-BLDTBXH issued on 30 July 2010. The objectives of these policies are set out as below:

- Provide annual vocational training for approximately one million rural labor (with 4,700,000 laborers and 5,500,000 laborers trained in the periods 2011-2015 and 2016-2020 respectively);

- Improve quality and efficiency of vocational training to create jobs and improve income for rural labor, contributing to shifting the labor structure and economic structure of rural areas serving modernization and industrialization of rural agriculture.

Beneficiaries of Project 1956 include 3 groups: (1) rural labor who are entitled to preferential policies (people with meritorious services to the revolution, poor households, minority ethnic people, people with disability, people subject to cultivation land recovery); (2) rural labor categorized under households with maximum income equal to 150% of poor households; (3) other rural laborers who have demand for vocational training.

Project 1956 proposes five groups of measures, comprising (1) Communication, (2) Support for training facility development, (3) Develop teams of trainers and administrative staff, (4) Develop curriculum, and teaching materials, (5) Support for rural labor participating in vocational training.

Funds for the Project come from the central and local state budget. In addition to state budget, local governments also allocate their budget to ensure the efficiency of the Project. Provincial PCs are responsible for balancing budget for the Project execution, which comes from regular training budget, other programs and projects on vocational training for rural labor within their localities. Joint Circular 112 also specifies the cost norms for facility investment, teaching material and teaching aid development, and fees for experts.

In the implementation process, all necessary steps including organization structure, vocational training need survey, project planning and communication were undertaken in accordance with regulations. However, according to our survey of 146 trainees in seven provinces, only 3.5% of who was aware of post-training support. The interviewees only knew that the training programs would provide subsidy for tuition fee, meals and travelling expenses if they are eligible. Besides, communal leadership in seven out of 21 surveyed communes neither mastered basic contents of Project 1956 nor was confused between the Project training programs and other training and agricultural extension activities.

The identification of vocational training needs at provincial level was not close to practical needs due to both subjective and objective reasons. Some provinces acted slowly and encountered difficulties in compiling training needs. For example, according to Quang Nam Province’s DOLISA, although Project 1956 was implemented for 2 years, 4 districts did not develop training plans, even some districts did not establish the district steering committee for project implementation. A number of communes under districts and cities did not have project implementation bodies. In Lam Dong and Binh Phuoc, the annual training program was based on the upper level plan, and the number of trained labor target was from the NRA targets. This fact reveals the inadequacy in identifying training needs.

Regarding the selection of trainees for vocational training: the survey conducted in seven provinces reveals that the selection process was assigned to local unions (mainly farmers union, and women union). 47.6% of interviewees claimed that they were informed by local authorities and thereby they registered for the training. This is the most commonly used method for trainee recruitment. However, appointment of trainees still happened (with a rate of 27.6%) although this measure does not fully satisfy the practical needs of the local residents. This way of conduct often happened in poor households and preferential households. Besides, a large number of labor have actively registered for what training program they wished to pursue (with 22.8%), this often happened with middle-income and rich households, and labor in Binh Phuoc where rubber tapping is quite popular and can generate jobs for the locality. These facts prove that those who directly registered for training programs often had better career orientation; thereby post-training often reached high level of efficiency. This is the issue that is worth considering in steering and organizing training program for rural labor. This outcome also points out weaknesses in the selection of trainee: 4.1% of interviewees revealed that they came to learn a job but not for the purpose of pursuing work in that field, 8.2% of trainees claimed that they registered for tuition fee and meals’ support.

Different localities impose different cost norms for training by categories. Many provinces mistook training expense alone with state budget support for categories of training, which led to low training cost, and training facilities’ loss of motivation to provide training. For example, total budget for agricultural training class was VND 10,773,700 (equivalent 490 US$) per class inclusive of all training cost, instructors’ wages, and other supporting fees. Training cost norms remain relatively small, particularly in jobs that require the purchase of breed and practising materials. According to some provinces, due to low cost norms, short-term training courses were often selected. Agricultural training courses were considered long-term ones, and handicraft training courses were no different from agricultural extension training courses.

The survey done in seven provinces also indicates that provinces did not spare a budget for job generation after training. Provinces like Ha Tinh, Binh Phuoc and Kien Giang have complied with the rules on beneficiaries and cost norms as stipulated by the guiding circulars. Tam Phuoc commune in Quang Nam province provided meal allowance for other trainees (type 2 and 3) who fell out of the beneficiary scope. Lam Dong Province provided support to those who enrolled in primary, secondary and tertiary training at other training institutions (not in accordance with the guidelines of Joint Circular 112). Basically, provinces prioritized the selection of trainees who are entitled to meal and travelling allowance.

In terms of training occupations, the survey shows that vocational training for rural labor mainly focused on courses of less than three months (representing 76.6%). Agricultural occupations account for a large proportion in the training structure (60%). Agricultural occupation training provided advanced training rather than new occupation introduction (87.5% of trainees had practiced the trained occupation prior to participating in the training). In surveyed localities, training focused on popular crops like growing and caring for coffee (Lam Dong), rice cultivation and breeding (Kien Giang). These were the jobs that trainers previously or currently participated in. In provinces with high proportion of elementary training (including Binh Phuoc and Nam Dinh), the training courses did not exceed three months; for example, rubber tapping training course lasted in 66 days in Binh Phuoc, and garment making training lasted in 60 days in Nam Dinh). With respect to non-agricultural occupations, the survey found that training courses were only introductory courses (for those who did not have previous knowledge of the occupation), and fundamental knowledge strengthening for those who knew about the occupation. Therefore, the applicability and job opportunities for trainees are not high, and most enterprises will have to retrain the trainees once they are recruited.

Results of policy on vocational training for rural labor

The total budget for vocational training sourced from central state budget for four years (2010-2013) was VND 4,806.663 billion (equivalent 218.49 million US$), accounting for 18.5% of total estimated budget for the Project by 2020.

Over four years from 2010 to 2013, more than 1.615 million rural labor received training, representing 22.9% of total rural labor entitled to training program of the Project 1956 over the course of 11 years (2010 - 2020). Approximately 1.2 million trainees found new jobs, were recruited by enterprises, or continued their previous occupation at higher productivity and with larger income (constituting 79%).

There were 62,073 people of poor households who found jobs and levitated themselves off the poor category, representing 35.2% of poor residents participating in training (the figure for poor residents participating in vocational training was 176 thousand people); 49,794 trainees found job and generated income higher than the local average income, and accounting for 4.2% of trainees who found job after training.

The total number of trainees in agricultural occupations was 231,119, of which female trainees occupied 39.6%. Of the 212,141 rural laborers completing agricultural occupation training courses, 79.5% of these trainees found jobs. There were also 761 people who participated in agricultural occupation training for rural labor; and 12,705 instructors participated in providing training. A number of MARD training facilities and institutions as well as provincial agricultural extension centers and training centers have been attracted to provide the training services. In some localities, local authorities, training facilities and enterprises cooperated in providing training and creating jobs for employees.

MARD has piloted the issuance of agricultural vocational training card for 10,299 laborers and trained 9,757 rural laborers under the card issuance format. The pilot results have been reported and are now waiting for Prime Minister’s feedback.

Assessing the impact of vocational training for rural labor

Job creation and new job creation

The survey results present that 85.6% of the trainees found job after finishing the vocational training course. However, the proportion of pursuing occupation trained in the service and commerce field made up a small number of 20%; while the figure for agriculture was much higher at 92.1%. The reason is agriculture and forestry trainees are those who have been working in the same field. Also, poor people are those who have the lowest percentage of pursuing the same occupation as trained (68.4%)

Fourteen percent of the trainees did not find jobs after completing the training course. The reasons for this fact include: trainees did not find relevant jobs; trainees did not want to pursue jobs in the trained occupation; trainees lacked skills to do the job, lacked investment to practice; no relevant jobs were available in the locality. The survey results also showed that only 30.8% of trainees learned new occupation, 21.9% of trainees practiced new job after completing the course; and 15.1% of trainees continued to pursue what they learned in new occupation. Those who did not find employment after vocational training claimed that the chance of finding the job was not high (accounting for 62.7%)

Primary and short-term vocational training offer a chance for trainees to work in enterprises. The statistics reveals that 6.2% trainees landed jobs in enterprises although they had not worked in enterprises before. Vocational training also increases employment opportunities for rural labor in local production facilities.

As a result, the impacts of vocational training on creating new jobs for rural labor are not really clear. The reasons include:

- For agricultural occupation: commune and district authorities did not have suitable production plans, and vocational training was not connected to production planning, specialized production planning, and production area planning. Thus, this activity did not attract large labor force to participate in agricultural production, nor created new jobs in agricultural sector.

- The policies attracting business to invest in agricultural and rural sector in accordance with Decree 61 were not effective and did not create any demand for labor in rural areas.

- Handicraft production largely depends on market. Handicraft product consumption linkages were weak and unsustainable. In Tam Phuoc commune of Quang Nam province, trainees after completing bamboo and rattan handicraft course only work in one year. Till now 95% of labor in bamboo and rattan handicraft has stopped working because the products are unsalable. The linkage with exporting corporate is suspended due to economic crisis. A similar situation is also seen in Tan Hoi commune (Lam Dong province).

- The trained occupations did not satisfy the market demand. Short-term courses in handicraft, industrial sewing, and woolen crotchet usually taught 1 type of product while the market demands are diverse and subject to change. Thus, rural labor found it too challenging to adapt, and often gave up. The professional awareness of farmers remained quite low, and easily changed. After finishing vocational training, they got quite low income, resulting in the lack of motivation to work for long term.

Impact on production

Close to 35% of trainees said that their production scale expanded after completing the training course, with an average increase of 150%.

Local experience shows that vocational training helps expanding production scale if the locality has good production plan (Tam An commune of Quang Nam province: the planning of specialized vegetable production area in combination with vocational training helped increase income and create jobs for rural labor); and links to supporting post-training policy (Tam Phuoc commune of Quang Nam province: repairing agricultural machines’ training combining with policies to provide 30% subsidy to procure agricultural machines resulted in an increase of 40% in application of mechanics in agricultural production); identifies right training need (traditional occupation training in noodle making by machine in Gia Pho – Ha Tinh helped increase production scale by 30%).

Impact on labor’s income

Around 58% of trainees supposed that their income has risen by 35.4% on average due to training.

Handicraft training courses have brought about positive effect in income generation to trainees, 65.8% of respondents claimed an increase of 43.8% in income as handicraft primarily uses labor after harvest time, and the materials are available in the locality. With respect to agricultural occupation training courses, 60.5% of respondents stated an increase of 34.5% in income. Occupations related to services and commerce did not show any impact on trainees’ income. As a result, vocational training for rural labor has started to positively affect the income of trainees.

Impact on rural labor structure

Regardless of several challenges, vocational training for rural labor has started to show positive impact on rural labor structure. Along with investment in infrastructure development, production, and technology transfer, vocational training at pilot communes has rapidly reduced the proportion of agricultural labor in 2011 compared to that of 2009.

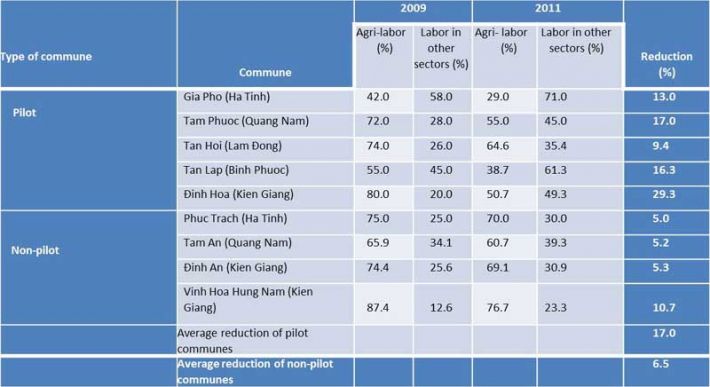

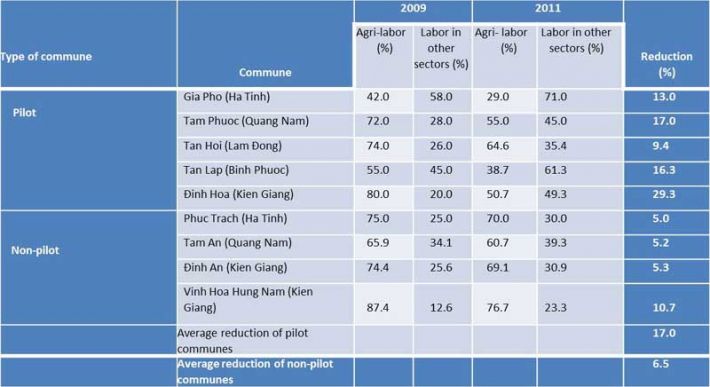

Table 3. Changes in labor structure in communes

Source: IPSARD, 2015

Impact on communal income per capita

The proportion of post-training employment and proportion of production scale expansion remained low; however, in general, vocational training for rural labor positively contributed to improving income per capita of communes. Pilot communes organized more training courses than non-pilot communes did. As a result, pilot communes enjoyed greater increase in income per capita (79.1%) with VND 21.1 million per capita per annum. Non-pilot communes saw a slower increase (59%) with VND 14.1 million per capita per annum.

Some limitations of policies on vocational training for rural labor

Although more than 1.6 million rural labor have received vocational training over the past four years, some limitations remain in this activity as follows:

- Vocational training for rural labor is lack of orientation, and not linked to the national target program on NRA development, and policy on agricultural sector restructuring.

- Vocational training currently focuses on traditional occupations, does not include new occupations. Agricultural occupation training has focused on providing training for rural labor to continue what they had previously done.

- Vocational training for rural labor does not closely link to employers like enterprises and cooperatives.

- Inspection and monitoring of vocational training for rural labor as well as communication and career counseling have not been well implemented.

The reasons for the above limitations:

- Low cost norms for training (particularly with occupations requiring the purchase of seedlings) affect training quality.

- Low wages for instructors make it exceptionally difficult to recruit good instructor; low allowance for trainees (inclusive meal and traveling expenses) does not appeal to labor to participate in training.

- In some localities, the training methodology lacks flexibility, which causes difficulties for trainees.

- Slow disbursement, which usually occurs at the end of the year, leads to trainings being organized at the end of the year, affecting the training quality.

- Currently, in addition to Project 1956, other programs and projects also offer vocational training for rural labor. As a result, the resources for rural vocational training are dispersed, duplicated, causing difficulties in monitoring, data synthesizing, and training efficiency.

CONCLUSION

Conclusions on the positive and negative impacts of NRA development policies

Infrastructure development policies

The infrastructure has significantly contributed to developing production and improving the lives of rural residents. The quality is satisfied. The general quality of production and living conditions has become better. Health care at communal health stations, education conditions, cultural activities and environmental quality have been improved. Infrastructure development also helps communes speed up the achievement of NRA targets (including both infrastructure targets and other targets).

Limitations in infrastructure development lie in the fact that local authorities focused significantly more on infrastructure development in pilot communes. This resulted in the uncontented feelings of non-pilot communes. However, the government has instructed local authorities to allocate equal budget for all communes. Besides, the delay in transferring some infrastructure works into use has also reduced the impact of NRA on production and living conditions.

Vocational training for rural labor policies

Localities have actively implemented the Project 1956. Provinces developed their own projects and issued guidelines for project implementation. Most districts appointed officials in charge of vocational training issues. However, some districts did not seriously conduct the training demand assessment, nor developed district training plan.

The assessment of vocational training demand for rural labor prior to project development was not conducted well. The human capacity for this task was weak; meanwhile, local labor did not accurately identify their own needs.

Local authorities often develop training plan on an annual basis (identifying training needs) through two main channels, i.e., training demand submitted by communes, and training proposals submitted by vocational training facilities. On the basis of central approval on the number of training classes and budget allocated, provincial authorities will allocate the equivalent number of classes and budget to districts and training facilities. This way of conduct reveals some limitations such as lack of connection with training demand and reducing implementation flexibility.

Preferential beneficiaries are entitled to higher tuition fee subsidy plus meal and traveling expense allowance, they are often those selected by local authorities to participate in training. Frauds were also detected, in which there were cases of trainees participating in preferential training groups 3 times.

Most training facilities and local authorities selected those who were doing the same occupation to participate in training.

Basically, elementary and short-term courses are introductory courses providing fundamental knowledge and skills, particularly in traditional occupations. For such occupations, more advanced skills and techniques are often mastered by several craftsmen; however, they are not willing to provide training on a large scale for fear of losing their secrets. Some localities proposed an initiative of combining craftsmen in training to educate trainees who then would work for the craftsmen. However, due to low wages, this proposal did not appeal to craftsmen.

Regarding financial mechanism: budget is allocated on the basis of classes/ courses approved by the central government. As a result, it lacks flexibility when being applied at local level, particularly under frequent changes in training demand.

The number of agricultural occupation training facilities, and the number of instructors has risen over the course of four years. Local authorities, training facilities and enterprises have connected in training implementation and job creation for workers.

The elementary and short-term vocational training as stipulated in Project 1956 has positively affected workers, farming households and new rural communes. The positive impact is shown in various aspects, such as enhancing the workers’ skills so that they can continue working in the same field or find new jobs, expanding the production scale and income, and changing the labor structure of the NRA.

Recommendations on finalizing 2 NRA policies

Recommendations on Infrastructure Development Policy

- Central state budget for NRA development has been relatively low over the past years. Infrastructure development at communal level requires relatively large investment. In the meantime, to maximize community participation, it is necessary to prioritize the completion of village infrastructure works. Hai Hau commune’s experience set an example for implementation. The launch of NRA development at village level attracted positive participation, resulting in more practical and suitable efficiency in accordance with local people’s aspiration.

- Due to shortage of budget for NRA development, it is suggested that a bank loan scheme can be piloted allowing village community to borrow money for investment in infrastructure for a certain period of time. State budget shall be used to back interest, and communal PCs shall act as the representative to make bank loan. There must be detailed investment plan submitted along with the commitment document of the Board for Rural development, in which signatures of the entire households within the village must be collected. The reason for this is that NRA development is a great target; however, the ending of phase 1 is 2015, which means there are only two years left. The mobilization of capital within the community is almost impossible within a relatively short time. Capital is needed to construct infrastructure works, local residents have to agree on the annual contribution to pay back the bank loan.

- Budget planning is necessary for communes; thus, it is crucial not to concentrate budget on pilot communes to avoid disputes among local residents and create a movement of NRA development.

- Currently applicable regulations on community participation in small scale infrastructure works (works that require less than VND 3 billion, equivalent 136.364 US$) and works that do not require high-tech must be amended. The amendments should specify which works shall be implemented by local community, for example, inter-village roads, inter-field irrigation, and inter-field roads.

Recommendations on vocational training for rural labor policy

- Policy on vocational training must become uniform to integrate all current policies on vocational training. Also, it is important to prioritize vocational training for preferential beneficiaries including people with meritorious services to the revolution, poor households, minority ethnic people, people with disability, people subject to cultivation land recovery, and fishermen.

- The selection of training occupations and trainees must be reformed. Specifically, short-term training will only be conducted with particular employers. Thereby, training must be conducted in line with employment order from enterprises, cooperatives and communal PCs. Training courses must be in compliance with business activities of enterprises and cooperatives as well as the communal production planning.

- Communal PCs must identify training demand and propose proper training courses in line with their communal production and business strategy. Communal PCs must be responsible for identification of training occupations and trainee groups.

- The list of occupations, particularly agricultural occupations, must be screened. Occupations applying high-tech, green-tech, pollution reducing tech, and new occupations in suburban areas must be prioritized for training. For mountainous areas with difficult accessibility, training must focus on improving rural labor skills in occupation they are doing. In mountainous areas, the majority of labor is working in agricultural sector with low productivity; hence, it is important to stay focused on agricultural training.

- District production planning development must be promoted to facilitate the selection of training demand in communes.

- Communication needs promoting. Communication has remained weak over the past years, which merely stops at introducing vocational training policies, providing knowledge for implementing officials. This task hasn’t paid attention to strengthening the knowledge for trainee groups. As a result, together with communication on NRA development, it is necessary to educate the local about their roles in training participation. Thereby, labor’s awareness is improved so that they can clearly identify their own training needs and the reasons for their participation in training programs. Once trainees have better understanding of the training necessity, training quality will be improved. In mountainous areas, word-of-mouth is the best communication method. As a result, using those who already experienced and succeeded in applying what they had been trained in communication is an effective method.

- Budget allocation mechanism must be reformed. The central government should allocate budget for local governments at the beginning of the year or announce the amount of budget at the beginning of the year so that local governments can actively implement proper budget disbursement to avoid much training crammed at the end of the year.

- Cost norms for trainees’ allowance and instructors’ wages must be amended in compliance with central government’s norms if central budget is used. In case local budget is used for training, these cost norms shall be regulated in accordance with the financial condition and capability of provinces.

- Meal and traveling allowance for preferential beneficiaries must be adjusted properly. This allowance must increase for those from particularly difficult and mountainous areas. There should be 2 types of allowance including allowance for training within commune, and allowance for training outside commune. Regarding the currently applicable regulations, training courses are often organized within the communes and usually lacks participants. As a result, households without training needs are also requested to participate in to meet the number of trainees required.

- Allowance for craftsmen must increase to become more appealing for their participation in training for rural labor.

- Information and forecast of labor market for rural labor must be strengthened.

- A provincial training monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system must be developed. Trainees’ evaluation feedback in terms of quality and appropriateness must be collected. Annual M&E activities must be conducted.

REFERENCE

Hoang Vu Quang (2016). Impact Assessment of New Rural Area Policy. MARD, 2015-2016. Non-published report in Vietnamese only.

IPSARD. 2015. Survey in New Rural Area Policy realization. Working report in Vietnamese.

Date submitted: July 27, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Oct. 15, 2018 |

Assessing some impacts of policies regarding New Rural Areas in Vietnam

Introduction

The National Target Program (NTP) on developing New Rural Areas (NRA) in Vietnam was implemented in accordance with Decision 800/QĐ-TTg issued on 4 June, 2010 by the Prime Minister (hereinafter referred to as Decision 800). This program has an overall objective of “developing NRA with modern socio-economic infrastructure, appropriate economic and production structure, linking agriculture with quick development of industry and services; linking rural and urban development as planned; developing democratic, stable and rich cultural identity in rural areas; preserving the ecosystem; maintaining social order and security; and improving the physical and mental life of people in accordance with socialism orientation”. The specific objective of this program is that by 2015 20% of communes would meet NRA targets; and 50% of communes will meet NRA targets by 2020.

The development of NRA has encountered a number of difficulties and obstacles over the past years. The government, ministries and related bodies have issued a variety of supporting policies, yet none of the research has fully evaluated the application and impact of these policies to the development of NRA. Thus, an impact assessment study on these policies is essential to enable the government to consider the impact of issued policies, and timely make further adjustment to the policies if needed.

This study was carried out on a nationwide scope, focusing on localities participating in NRA pilot program in the period of industrialization and modernization acceleration. These provinces are those with communes that have taken part in NRA policies development at early stage. As a result, they offer the basis for analysis and comparison of policy impacts. Seven provinces were selected to represent socio-economic regions of the entire country for the survey. Commune is the grassroots level for developing NRA. Commune level is where the majority of projects or programs on NRA was undertaken, and NRA targets also take commune as grassroots level. Therefore, the spatial scope for impact assessment study is also inclusive of communal level, specifically, the impact of rural development on local beneficiaries. Information and data for the study are collected from 2009 when the NRA pilot program commenced until the end of 2013.

Summary of some NRA policies in Vietnam

NRA development targets

The development of NRA program contains 11 main contents, including:

Supporting policies on NRA development

There are four primary sources of funding for NRA development. These include (i) state budget (inclusive of central and provincial state budget, which becomes direct funding for the program) (accounting for 40% of the total funding); (ii) credit (representing 30%); (iii) corporate investments (constituting 20%); and community contribution (occupying 10%).

Decision 800 and Decision 491 are two legal instruments setting out the orientation for NRA development; there are also a number of guidance issued by ministries providing support for each contents of NRA development. It is possible to divide these policies into two main groups as written below:

Direct support policies: include direct support for communes to execute the 19 targets of NRA. Relevant ministries and bodies preside over the proposal to the government for issuing specific regulations on investments and support.

Indirect support policies: include policies supporting the development of NRA, indirectly impact on the achievement of NRA targets; for example, policies on vocational training for rural labor, policies on bringing young intellectuals to rural areas; credit policies, policies encouraging enterprises to invest in rural areas and agriculture in general.

In this paper, I will focus on evaluating two important NRA policies, namely the policy on socio-economic infrastructure development, and the policy on vocational training for rural areas.

Impact Assessment of two NRA policies on rural infrastructure and labor training

Policy on socio-economic infrastructure development

Overview of policies

Socio-economic infrastructure development is the second in the 11 contents of NRA development. This content includes seven activities: (1) complete road traffic to commune people’s committee’s office (PC office) and road traffic within the commune; (2) Complete the electricity system to supply daily life and production needs in the commune; (3) Complete works serving the cultural and sports demand of the commune; (4) Complete works serving the standardization of health care in the commune; (5) Complete works serving the standardization of education; (6) Complete commune PC office and other auxiliary works; and (7) Renovate and construct new irrigation system in the commune.

Joint circular No. 26 issued by MARD, MPI and MOF provides detailed guidance on socio-economic infrastructure development. Particularly, Decision 800 also specifies that the State budget shall provide full (100%) funding for five works mentioned above. However, as of 8 June 2012, the Prime Minister issued Decision 695/QD-TTg to adjust the funding, in which only commune PC’s office would receive full funding, four other works would only receive partial funding in compliance with the decision of provincial people’s council, and the funding source was generally stated as state budget (including both central and local state budget).

In the implementation of this policy, localities set priority to spend various resources on infrastructure development, which is the primary factor to reform rural areas, creating momentum for socio-economic development, and benefiting local residents. A number of localities have actively issued flexible mechanism that fits their own particular conditions to mobilize resources for infrastructure investments.

In accordance with the regulations, the commune’s New rural area (NRA) project is developed and approved by district People Comitee (PC). Thereafter, detailed plan will be made by NRA development management board (MB) when each construction item for NRA is deployed.

New rural area (NRA) communes of central government have been deployed since 2009. As the very first pilot communes, they received significant funding from the state budget as well as other programs and projects. On the other hand, pilot provincial communes, having commenced since 2011, received less funding. As a result, only several small-scale works, renovation and refurbishment were invested in these communes.

In accordance with Decision 800, infrastructure works specified within the scope of this paper (including PC’s office, roads, health station and commune cultural and sports centers) receive full (100%) funding from state budget. Therefore, communal authorities did not mobilize funding from community. In fact, according to our field-study, the community did not financially contribute to these works.

As stipulated by regulations, the development priority must have community counseling. In our field-study, NRA development management board only counseled and received consensus from the commune people’s council, which has representatives of villages and relevant bodies. This way of conduct does not violate the regulations on democracy at the grassroots level. Circular 26 requires community counseling yet does not specify how to conduct such counseling. As a result, the management board only counseled the commune people’s council for infrastructure works that did not mobilize community financial contribution.

The majority of communes focused their funding on developing infrastructure, as this played as the face of the rural areas. Also, this development received full funding from the state budget, and it was relatively easy to execute. Meanwhile, capital needed for production was relatively lower. Households wished to receive more investments in works at villages.

The NRA development pilot appointed to the party secretariat in 11 communes ended at the end of 2011. However, till the beginning of 2013, a number of socio-economic infrastructure items in pilot communes were not finalized or were finalized yet not put into use. The reason for this fact is the lack of funding. Some communes allowed private corporate to advance their fund for the construction of these items and hoped that the state budget would be received later, or the commune PC would sell land (permitted) to pay back the advancement. However, due to the lack of funding or difficulty in sale of land, some communes accumulated large amount of private debt. For example, Thuy Huong commune (Chuong My District, Hanoi) owed more than VND 60 billion, or Hai Duong commune (Hai Hau District, Nam Dinh Province) had to suspend the completion of its office due to insufficient funding.

Another point to consider is that some communes had to mobilize various sources of funding for infrastructure works by integrating different resources. That disbursement and settlement mechanism of different funding sources vary, together with different technical norms, causes much complexity in the construction process.

All communes participated in the survey undertook the role of investors in all infrastructure development projects. At the beginning of the project, the commune authorities encountered a number of challenges when they had to handle a large number of documents and processes for each project. Meanwhile, the capacity of commune staff was limited; support had to be given from district authorities. After a while, commune officials became more familiar with the new process. However, to implement an infrastructure item from surveying, the designing is too complicated comparing to the building capacity of farmers.

Besides NRA pilot communes of the Party secretariat, other communes commenced NRA development in 2011. Due to low state budget allocation, particularly that from the central state budget, the primary activities in the early phase of infrastructure development included (i) finalizing management structure, (ii) communication, (iii) training and capacity building, (iv) NRA planning, and (v) developing NRA project.

The state budget was mainly allocated to the abovementioned activities, infrastructure development activities were initially implemented in some small projects. Infrastructure items were primarily works that received full state funding or combined funding. Some communes also deployed works at village level with the focus on village roads and village cultural center.

The survey reveals that communal authorities were active in communication and mobilization of resources for investments, thereby learning from the experiences of previously implemented communes. However, commune authorities often mentioned the following obstacles regarding socio-economic infrastructure development:

Results of implementing policy on socio-economic infrastructure development

Table 1. Results achieved by 7 pilot communes

Source: IPSARD, 2015

Assessing the Impact of infrastructure development policy

The five commune socio-economic infrastructure items, including commune office, health stations, schools, roads and cultural centers, will have an impact on the entire commune community from individuals to organizations once they are constructed. In general, the residents view infrastructure works as beneficial to the production development and improving quality of life of the rural population. The survey results of 111 households in seven pilot communes show that most of the people evaluated the investments in infrastructure works created better conditions for life, production, medical examination at health stations, studying at commune schools, participation in cultural and sports activities, and environment protection.

Table 2. Residents’ assessment of 7 pilot communes in terms of infrastructure

Source: IPSARD, 2015

As of May 2014, 98.3% of communes had roads to commune centers, 87.4% of which were asphalt and concrete. Local authorities affirmed that better roads enabled better transport and trading. The construction of commune cultural and sports center in compliance with standards has facilitated the residents to enjoy cultural, sports and social events. 83.8% of interviewees agreed with this view. For example, in Tam Phuong commune (Phu Ninh district, Quang Nam province), the residents were particularly content with the center as they can hold weddings in this place where commune leadership would make announcement and present gifts in this event which makes them feel proud and lessens the concern of wedding organization.

According to the report of the Central Steering Committee (CSC) in 2014, about 78.8% of commune health stations experienced medical examination and treatment using health care insurance. The proportion of villages and hamlets having medical staff reached 86%. Health care at grassroots level saw much improvement by expanding medical services at the commune level, piloting the management of several chronic diseases, which lessens the pressure onto upper medical level. Seventy-three percent (73%) of residents claimed that medical examination and treatment in pilot communes had been improved.

Investments in improving educational infrastructure have created more favorable conditions for rural students, which was rated as ‘improved’ by 68.5% of local residents. According to the 2014 report of the CSC, the number of kindergarten-goers rose by 15.8% compared with the figure for 2008; children going to preschools also increased by 11.4% compared with the figure for 2008. The system of boarding schools for minority ethnic students has also been improved, receiving from 7-12% of ethnic students’ enrolment. The tuition fee support policy applicable to ethnic students as well as student loans are adjusted to facilitate rural students’ pursuing education.

Due to better transport, trading of goods is also improved. This, in turn, makes production better, contributing to income generation for rural residents. A three-year report of NRA development stated that the rural residents’ income in 2013 grew by 1.8% times compared with that of 2010. The proportion of poor rural households in 2013 stayed at 12.6%, representing an average drop of 2% pa. compared with that of 2008.

Some limitations and inadequacies of infrastructure development policies

Policy on vocational training for rural labor

Overview of policies

Contents relevant to policies vocational training for rural labor (hereinafter referred to as Project 1956) are specified in Decision 1956/QD-TTg issued on 27 November 2009, and Joint Circular 112/2010/TTLT-BTC-BLDTBXH issued on 30 July 2010. The objectives of these policies are set out as below:

Beneficiaries of Project 1956 include 3 groups: (1) rural labor who are entitled to preferential policies (people with meritorious services to the revolution, poor households, minority ethnic people, people with disability, people subject to cultivation land recovery); (2) rural labor categorized under households with maximum income equal to 150% of poor households; (3) other rural laborers who have demand for vocational training.

Project 1956 proposes five groups of measures, comprising (1) Communication, (2) Support for training facility development, (3) Develop teams of trainers and administrative staff, (4) Develop curriculum, and teaching materials, (5) Support for rural labor participating in vocational training.

Funds for the Project come from the central and local state budget. In addition to state budget, local governments also allocate their budget to ensure the efficiency of the Project. Provincial PCs are responsible for balancing budget for the Project execution, which comes from regular training budget, other programs and projects on vocational training for rural labor within their localities. Joint Circular 112 also specifies the cost norms for facility investment, teaching material and teaching aid development, and fees for experts.

In the implementation process, all necessary steps including organization structure, vocational training need survey, project planning and communication were undertaken in accordance with regulations. However, according to our survey of 146 trainees in seven provinces, only 3.5% of who was aware of post-training support. The interviewees only knew that the training programs would provide subsidy for tuition fee, meals and travelling expenses if they are eligible. Besides, communal leadership in seven out of 21 surveyed communes neither mastered basic contents of Project 1956 nor was confused between the Project training programs and other training and agricultural extension activities.

The identification of vocational training needs at provincial level was not close to practical needs due to both subjective and objective reasons. Some provinces acted slowly and encountered difficulties in compiling training needs. For example, according to Quang Nam Province’s DOLISA, although Project 1956 was implemented for 2 years, 4 districts did not develop training plans, even some districts did not establish the district steering committee for project implementation. A number of communes under districts and cities did not have project implementation bodies. In Lam Dong and Binh Phuoc, the annual training program was based on the upper level plan, and the number of trained labor target was from the NRA targets. This fact reveals the inadequacy in identifying training needs.

Regarding the selection of trainees for vocational training: the survey conducted in seven provinces reveals that the selection process was assigned to local unions (mainly farmers union, and women union). 47.6% of interviewees claimed that they were informed by local authorities and thereby they registered for the training. This is the most commonly used method for trainee recruitment. However, appointment of trainees still happened (with a rate of 27.6%) although this measure does not fully satisfy the practical needs of the local residents. This way of conduct often happened in poor households and preferential households. Besides, a large number of labor have actively registered for what training program they wished to pursue (with 22.8%), this often happened with middle-income and rich households, and labor in Binh Phuoc where rubber tapping is quite popular and can generate jobs for the locality. These facts prove that those who directly registered for training programs often had better career orientation; thereby post-training often reached high level of efficiency. This is the issue that is worth considering in steering and organizing training program for rural labor. This outcome also points out weaknesses in the selection of trainee: 4.1% of interviewees revealed that they came to learn a job but not for the purpose of pursuing work in that field, 8.2% of trainees claimed that they registered for tuition fee and meals’ support.

Different localities impose different cost norms for training by categories. Many provinces mistook training expense alone with state budget support for categories of training, which led to low training cost, and training facilities’ loss of motivation to provide training. For example, total budget for agricultural training class was VND 10,773,700 (equivalent 490 US$) per class inclusive of all training cost, instructors’ wages, and other supporting fees. Training cost norms remain relatively small, particularly in jobs that require the purchase of breed and practising materials. According to some provinces, due to low cost norms, short-term training courses were often selected. Agricultural training courses were considered long-term ones, and handicraft training courses were no different from agricultural extension training courses.

The survey done in seven provinces also indicates that provinces did not spare a budget for job generation after training. Provinces like Ha Tinh, Binh Phuoc and Kien Giang have complied with the rules on beneficiaries and cost norms as stipulated by the guiding circulars. Tam Phuoc commune in Quang Nam province provided meal allowance for other trainees (type 2 and 3) who fell out of the beneficiary scope. Lam Dong Province provided support to those who enrolled in primary, secondary and tertiary training at other training institutions (not in accordance with the guidelines of Joint Circular 112). Basically, provinces prioritized the selection of trainees who are entitled to meal and travelling allowance.

In terms of training occupations, the survey shows that vocational training for rural labor mainly focused on courses of less than three months (representing 76.6%). Agricultural occupations account for a large proportion in the training structure (60%). Agricultural occupation training provided advanced training rather than new occupation introduction (87.5% of trainees had practiced the trained occupation prior to participating in the training). In surveyed localities, training focused on popular crops like growing and caring for coffee (Lam Dong), rice cultivation and breeding (Kien Giang). These were the jobs that trainers previously or currently participated in. In provinces with high proportion of elementary training (including Binh Phuoc and Nam Dinh), the training courses did not exceed three months; for example, rubber tapping training course lasted in 66 days in Binh Phuoc, and garment making training lasted in 60 days in Nam Dinh). With respect to non-agricultural occupations, the survey found that training courses were only introductory courses (for those who did not have previous knowledge of the occupation), and fundamental knowledge strengthening for those who knew about the occupation. Therefore, the applicability and job opportunities for trainees are not high, and most enterprises will have to retrain the trainees once they are recruited.

Results of policy on vocational training for rural labor

The total budget for vocational training sourced from central state budget for four years (2010-2013) was VND 4,806.663 billion (equivalent 218.49 million US$), accounting for 18.5% of total estimated budget for the Project by 2020.

Over four years from 2010 to 2013, more than 1.615 million rural labor received training, representing 22.9% of total rural labor entitled to training program of the Project 1956 over the course of 11 years (2010 - 2020). Approximately 1.2 million trainees found new jobs, were recruited by enterprises, or continued their previous occupation at higher productivity and with larger income (constituting 79%).

There were 62,073 people of poor households who found jobs and levitated themselves off the poor category, representing 35.2% of poor residents participating in training (the figure for poor residents participating in vocational training was 176 thousand people); 49,794 trainees found job and generated income higher than the local average income, and accounting for 4.2% of trainees who found job after training.

The total number of trainees in agricultural occupations was 231,119, of which female trainees occupied 39.6%. Of the 212,141 rural laborers completing agricultural occupation training courses, 79.5% of these trainees found jobs. There were also 761 people who participated in agricultural occupation training for rural labor; and 12,705 instructors participated in providing training. A number of MARD training facilities and institutions as well as provincial agricultural extension centers and training centers have been attracted to provide the training services. In some localities, local authorities, training facilities and enterprises cooperated in providing training and creating jobs for employees.

MARD has piloted the issuance of agricultural vocational training card for 10,299 laborers and trained 9,757 rural laborers under the card issuance format. The pilot results have been reported and are now waiting for Prime Minister’s feedback.

Assessing the impact of vocational training for rural labor

Job creation and new job creation

The survey results present that 85.6% of the trainees found job after finishing the vocational training course. However, the proportion of pursuing occupation trained in the service and commerce field made up a small number of 20%; while the figure for agriculture was much higher at 92.1%. The reason is agriculture and forestry trainees are those who have been working in the same field. Also, poor people are those who have the lowest percentage of pursuing the same occupation as trained (68.4%)

Fourteen percent of the trainees did not find jobs after completing the training course. The reasons for this fact include: trainees did not find relevant jobs; trainees did not want to pursue jobs in the trained occupation; trainees lacked skills to do the job, lacked investment to practice; no relevant jobs were available in the locality. The survey results also showed that only 30.8% of trainees learned new occupation, 21.9% of trainees practiced new job after completing the course; and 15.1% of trainees continued to pursue what they learned in new occupation. Those who did not find employment after vocational training claimed that the chance of finding the job was not high (accounting for 62.7%)

Primary and short-term vocational training offer a chance for trainees to work in enterprises. The statistics reveals that 6.2% trainees landed jobs in enterprises although they had not worked in enterprises before. Vocational training also increases employment opportunities for rural labor in local production facilities.

As a result, the impacts of vocational training on creating new jobs for rural labor are not really clear. The reasons include:

Impact on production

Close to 35% of trainees said that their production scale expanded after completing the training course, with an average increase of 150%.

Local experience shows that vocational training helps expanding production scale if the locality has good production plan (Tam An commune of Quang Nam province: the planning of specialized vegetable production area in combination with vocational training helped increase income and create jobs for rural labor); and links to supporting post-training policy (Tam Phuoc commune of Quang Nam province: repairing agricultural machines’ training combining with policies to provide 30% subsidy to procure agricultural machines resulted in an increase of 40% in application of mechanics in agricultural production); identifies right training need (traditional occupation training in noodle making by machine in Gia Pho – Ha Tinh helped increase production scale by 30%).

Impact on labor’s income

Around 58% of trainees supposed that their income has risen by 35.4% on average due to training.

Handicraft training courses have brought about positive effect in income generation to trainees, 65.8% of respondents claimed an increase of 43.8% in income as handicraft primarily uses labor after harvest time, and the materials are available in the locality. With respect to agricultural occupation training courses, 60.5% of respondents stated an increase of 34.5% in income. Occupations related to services and commerce did not show any impact on trainees’ income. As a result, vocational training for rural labor has started to positively affect the income of trainees.

Impact on rural labor structure

Regardless of several challenges, vocational training for rural labor has started to show positive impact on rural labor structure. Along with investment in infrastructure development, production, and technology transfer, vocational training at pilot communes has rapidly reduced the proportion of agricultural labor in 2011 compared to that of 2009.

Table 3. Changes in labor structure in communes

Source: IPSARD, 2015

Impact on communal income per capita

The proportion of post-training employment and proportion of production scale expansion remained low; however, in general, vocational training for rural labor positively contributed to improving income per capita of communes. Pilot communes organized more training courses than non-pilot communes did. As a result, pilot communes enjoyed greater increase in income per capita (79.1%) with VND 21.1 million per capita per annum. Non-pilot communes saw a slower increase (59%) with VND 14.1 million per capita per annum.

Some limitations of policies on vocational training for rural labor

Although more than 1.6 million rural labor have received vocational training over the past four years, some limitations remain in this activity as follows:

The reasons for the above limitations:

CONCLUSION

Conclusions on the positive and negative impacts of NRA development policies

Infrastructure development policies

The infrastructure has significantly contributed to developing production and improving the lives of rural residents. The quality is satisfied. The general quality of production and living conditions has become better. Health care at communal health stations, education conditions, cultural activities and environmental quality have been improved. Infrastructure development also helps communes speed up the achievement of NRA targets (including both infrastructure targets and other targets).

Limitations in infrastructure development lie in the fact that local authorities focused significantly more on infrastructure development in pilot communes. This resulted in the uncontented feelings of non-pilot communes. However, the government has instructed local authorities to allocate equal budget for all communes. Besides, the delay in transferring some infrastructure works into use has also reduced the impact of NRA on production and living conditions.

Vocational training for rural labor policies