Introduction

With the passage of time, Korean exports of agricultural products have undergone many changes. During the 1950s and 1960s, major agricultural exports included rice, cocoons, ginseng and tobacco. In the 1970s, canned mushrooms, chestnuts, mushrooms, arrowroot wallpaper, and oriental medicine herbs emerged as new export items while rice exports decreased sharply. Since the 1980s, the export of fruits, vegetables (kimchi, bell peppers, cherry tomatoes, eggplants, etc.), processed foods, pork and floricultural products, along with Korean traditional products such as ginseng, tobacco and chestnuts, increased significantly leading to diversification of Korea’s export products.

Trends in Korean agricultural export

Korea’s agricultural export increased from US$1.59 billion in 2000 to US$6.11 billion in 2015. Export to the largest market, Japan, increased from US$0.7 billion to US$1.17 billion during the same period. The largest increase in agricultural export was export to China, which has been the second largest export market for Korean agriculture since 2008, surging from US$118 million to US$1,048 million in the same period. Export to the United States has increased from US$145 million in 2000 to US$628 million in 2015, and agricultural exports to other major markets such as Hong Kong, Vietnam, Russia, the United Arab Emirates, and Taiwan have also increased significantly.

Traditionally, Korean agricultural export has been heavily dependent on the Japanese market. The dependency ratio for the Japanese market, however, has significantly lowered from 46.2 % in 2000 to 19.2 % in 2015. On the other hand, the ratio for the Chinese market has increased from 7.8 % to 17.1 % during the same period. The dependency ratio for the U.S. market has been slightly lowered from 9.7 %to 10.2 % during the same period. Korean agricultural exports to Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern countries including Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, Afghanistan, and Iraq have increased by more than five times during the same period. These countries have become emerging markets for Korean agriculture.

Table 1. Korean agricultural export by country

Unit: US$ Million

| |

2000

|

2005

|

2008

|

2010

|

2012

|

2015

|

|

World Total

|

1,509.1

|

2,221.5

|

3,048.2

|

4,114.6

|

5,341.1

|

6,107.3

|

|

Japan

|

697.1

|

713.3

|

752.5

|

1,184.1

|

1,591.4

|

1,168.1

|

|

China

|

117.6

|

231.2

|

349.1

|

523.3

|

785.3

|

1,048.1

|

|

United States

|

145.8

|

280.3

|

335.4

|

410.5

|

500.0

|

627.7

|

|

Hong Kong

|

134

|

123.7

|

162.7

|

220.2

|

258.3

|

347.7

|

|

Vietnam

|

8.8

|

17.3

|

55.7

|

125.5

|

256.8

|

293.6

|

|

Russia

|

74.2

|

203.8

|

286.3

|

214.5

|

234.3

|

129.8

|

|

United Arab Emirates

|

14.1

|

118

|

123

|

220.3

|

218.3

|

249.6

|

|

Taiwan

|

55.3

|

110.1

|

107

|

188.2

|

194.3

|

222.2

|

|

Indonesia

|

24.4

|

45.5

|

77

|

86.3

|

120.3

|

137.6

|

|

Philippines

|

29.7

|

27.8

|

48.7

|

89.8

|

101.2

|

115.7

|

|

Australia

|

15.9

|

40.1

|

72.1

|

79.0

|

96.8

|

110.7

|

|

Afghanistan

|

5.9

|

0.8

|

44.7

|

23.7

|

92.8

|

106.1

|

|

Singapore

|

18.2

|

21.8

|

33.3

|

81.8

|

87.6

|

100.2

|

|

Thailand

|

9.8

|

13.4

|

17.6

|

82.0

|

78.9

|

90.2

|

|

Malaysia

|

8.4

|

15.2

|

31.3

|

56.6

|

69.4

|

79.4

|

|

Canada

|

16.6

|

26.8

|

30.3

|

47.1

|

65.3

|

74.7

|

|

Mongolia

|

5.5

|

12.5

|

28

|

27.6

|

38.3

|

43.8

|

|

Iraq

|

-

|

1.2

|

106.5

|

114.9

|

73.7

|

34.5

|

|

Kazakhstan

|

4.3

|

8

|

27.4

|

25.5

|

34.6

|

32.5

|

|

Netherlands

|

7.6

|

6.6

|

62.5

|

16.1

|

23.7

|

25.7

|

Source: KITA

Until 2000, none of the exporting commodities exceeded US$100 million in Korea. The top export product was ramen (US$95 million), followed by soju (US$88 million) and chestnuts (US$ 84 million). The export value of bakery products and kimchi was US$78 million.

In 2015, the export value of filter cigarettes was US$887 million, followed by mixed prepared food (US$1,063 million). The export value of coffee products was US$272 million and that of processed sugar was US$151 million. The number of agricultural commodities exceeding the export value of US$100 million was 13 in total. The export value of ginseng in particular, which are representative fresh agricultural products in Korea, exceeded US$100 million, respectively

Table 2. Korean agricultural export by commodity

Unit: US$ Million

| |

2000

|

2005

|

2008

|

2010

|

2012

|

2015

|

|

Total

|

1,509.1

|

2,221.5

|

3,048.2

|

4,114.6

|

5,341.1

|

6,107.3

|

|

Processed food

|

Filter cigarettes

|

36.8

|

254.1

|

453.0

|

536.5

|

549.8

|

886.8

|

|

Mixed prepared food

|

1.4

|

1.2

|

152.4*

|

412.1

|

930.0

|

1,063.4

|

|

Coffee products

|

31.4

|

103.7

|

195.2

|

221.0

|

333.0

|

272.3

|

|

Processed sugar

|

71.6

|

94.0

|

127.7

|

242.1

|

291.2

|

151.4

|

|

Ramen

|

94.7

|

151.6

|

141.8

|

175.1

|

211.0

|

218.8

|

|

Beverages

|

11.6

|

36.5

|

64.4

|

102.6

|

184.1

|

293.6

|

|

Sauce

|

13.4

|

38.2

|

68.1

|

129.7

|

155.4

|

177.7

|

|

Bakery

|

79.0

|

110.8

|

142.4

|

110.3

|

131.5

|

149.9

|

|

Fermented beverages

prepared from cereals

|

18.0

|

9.1

|

33.4

|

97.1

|

137.9

|

12.9

|

|

Sugar, confectionery

|

76.6

|

82.1

|

94.6

|

100.2

|

134.2

|

153.5

|

|

Soju

|

87.9

|

116.2

|

124.1

|

123.1

|

114.3

|

87.8

|

|

Beer

|

19.0

|

38.1

|

43.3

|

46.8

|

65.4

|

84.5

|

|

Prepared, dry milk

|

3.5

|

9.3

|

24.0

|

24.4

|

36.2

|

41.4

|

|

Prepared grain food

|

14.0

|

31.7

|

25.0

|

45.3

|

58.6

|

67.0

|

|

Citrus (prepared or

preserved)

|

-

|

-

|

27.1

|

32.6

|

40.4

|

46.2

|

|

Feed

|

0.7

|

10.6

|

18.9

|

37.3

|

41.7

|

47.7

|

|

Pasta

|

11.5

|

21.0

|

28.4

|

29.0

|

13.8

|

15.8

|

|

Soybean meal

|

-

|

0.1

|

21.9

|

22.2

|

32.4

|

37.0

|

|

Gelatin

|

7.1

|

10.4

|

19.1

|

20.9

|

22.5

|

25.7

|

|

Noodles

|

9.7

|

13.5

|

24.4

|

27.6

|

34.1

|

39.0

|

|

Fresh agricultural products

|

Ginseng root

|

60.3

|

62.0

|

75.9

|

96.8

|

155.5

|

155.1

|

|

Kimchi

|

78.8

|

93.0

|

85.3

|

98.4

|

104.6

|

73.5

|

|

Paprika

|

-

|

53.1

|

54.2

|

58.3

|

65.9

|

85.2

|

|

Pear

|

17.1

|

56.1

|

47.3

|

54.1

|

47.3

|

58.4

|

|

Lily

|

4.3

|

10.5

|

19.1

|

27.8

|

33.1

|

9.3

|

|

Rose

|

10.3

|

10.4

|

11.8

|

34.2

|

25.7

|

3.3

|

|

Winter mushrooms

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

11.3

|

26.3

|

22.6

|

15.6

|

|

Apples

|

1.8

|

7.7

|

9.2

|

17.9

|

8.9

|

8.7

|

|

Chestnuts

|

84.1

|

35.0

|

23.6

|

12.6

|

10.2

|

11.7

|

Source: KITA

Korean agricultural export promotion policies

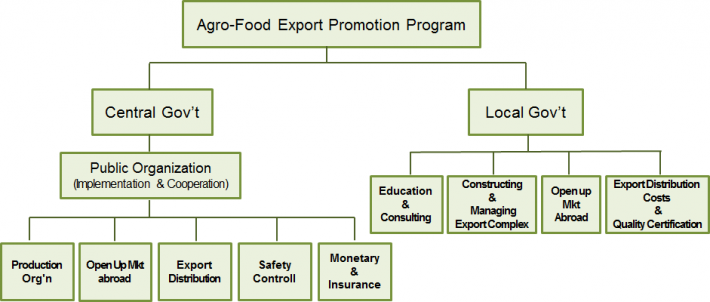

Korean agricultural export promotion policies (EPP) can be categorized according to the branch of government that dictates the subject of the program: central government and local government. The central government usually implements agricultural EPPs through public organizations, such as the Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corporation (aT). The types of agricultural EPPs executed by the central government have been changing over time, and can now be sorted into five supporting programs related to producers opening markets abroad, organization production, export distribution, safety control, and monetary and insurance (Figure 1). Local governments, however, directly implements some EPP projects of their own, with policies related to education and consulting exports business, construction and managing export complexes, supporting the opening of markets abroad, and payment for export distribution costs and quality certifications.

Agricultural EPP of the Central Government

Support for organizing production

Backed by the central government, the aT supports production organization projects to secure stable quantities of agricultural products for export. Most farmers cannot meet the orders from buyers abroad due to their small-scale operations, thus, they need to coordinate with their peers in the industry before they can supply agricultural products for export. Increasing the output of numerous small and micro-scale farms can be possible only through a coordinated effort, and the following organizations have taken on the task: the Horticultural Production Complex, the Fostering Potential Export Products, the Human Resource Development Specialized in Export, the Export Leading Organization, and the Export Council Meeting. The government budget to support these projects has increased from KRW 117 million in 2000 to KRW3.04 billion in 2015.

Table 3. Korean agricultural EPP

Unit: KRW Million

| |

2000

|

2005

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2012

|

2015

|

|

Support for organizing production

|

117

|

596

|

1,768

|

4,532

|

3,853

|

1,700

|

3,040

|

|

Project for supporting opening up overseas markets

|

8,075

|

11,467

|

15,106

|

18,681

|

22,737

|

29,490

|

32,100

|

|

Supporting export distribution projects

|

19,081

|

26,266

|

31,561

|

39,743

|

39,373

|

31,078

|

32,975

|

|

Safety Control

|

-

|

120

|

127

|

119

|

154

|

139

|

142

|

|

Monetary and insurance supporting policy

|

25,300

|

28,000

|

323,000

|

343,000

|

360,200

|

365,200

|

420,100

|

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (2015)

Figure 1. Korean agro-food export support System

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (2015)

Project to support opening of the overseas markets

An overview of projects and tasks aimed at supporting the opening of overseas markets includes sales promotion events with foreign distribution enterprises, participation in international food exhibitions, arranging buyer introductions, registering export brands in foreign countries, registering certification system abroad, and management for the government’s own agriculture brand "Whimori," among others.

Support for export distribution project

Export distribution support policies are designed to help logistics and sales promotions. Detailed sub-projects of the export distribution supporting policy contained in the Distribution Costs payment program, which the WTO’s agricultural agreements allow. In addition, Supporting Preservative Costs program and the Sharing Terminal Handling Charge program are also included in this area. The budget for supporting export distribution has increased from KRW 19.1 billion in 2000 to KRW 32.97 billion in 2015, which is the largest amount of subsidies in agricultural EPP projects. Their growth rate, however, is lower than that of any other project, which may imply that this kind of support is prohibited by the WTO and tends to be diminishing.

Support for safety control

The objective of the safety control support policy is to strengthen food safety. The Supporting Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) Certification Fee project and the Sharing Pesticide Test Fee project are included in this policy. The budget for safety control is almost stagnant, having been valued at KRW 142 million and KRW 139million in 2000 and 2015, respectively.

Monetary and insurance support policy

The purpose of the monetary and insurance support policy is to help farmers with poor access to finance and insurance participate in export insurance and operate capital loans. The Exchange Rate Insurance Fee and Export Insurance Premium projects are included in this area. Since this kind of support is a loan rather than a subsidy, the budget for this project is larger than that of other central government EPP projects in Korea, increasing from KRW 253 billion in 2000 to KRW 420.1 billion in 2015and accounting for 53.1 % of the total agricultural EPP budget.

Agricultural EPP of the local government

The purpose of agricultural EPPs initiated by local governments is to encourage the export of locally produced agricultural commodities and to increase the income of farmers. There are various kinds of EPPs at the local government level, such as education and consulting for export businesses, construction and management support for export complexes, support for the opening of overseas markets, support for the logistic costs for exporting, and support for quality certifications, etc. However, the budget is solely focused on supporting logistical costs for export distribution. The budget for this project increased from KRW 26.7 billion in 2007 to KRW 45.7 billion in 2013. Even though the share of the budget for this project was reduced from 76 % to 68 % during the same period, it still maintained over two-thirds of the budget for local government EPP.

Outcomes of the agricultural EPP and its limitations

One of the previous studies showed that 10 % increases in the government’s support for export logistic costs increased exports by 2.3 %. In addition, 10% increases in the government’s support infrastructure investments for export can raise export by 4.7 % in the long run. This result can be utilized as a guide to agricultural EPP in Korea: progressively expanding support for export infrastructure while gradually reducing support for export logistics in the medium- and long-term.

Agricultural EPP appeared to have effects on increasing production and expanding employment in the national economy. National expenditure for agricultural EPP which was KRW 2.5 trillion during 2008–2014, resulted in net increments of national production of KRW 4.5 trillion of national production and employment of 8,800 in three years. Meanwhile, there are some limitations to Korea’s agricultural EPP. First, even though the budget for supporting export logistical costs should be reduced due to the financial burdens of the government and negotiation trends concerning the WTO/DDA, there is no alternative measure. Since farmers and exporters want the government to continue to provide support in the future, it is inevitable that the disputes on this issue will persist.

Second, the performance of some projects, such as the Supporting Export Leading Organization, was negligible. This project aimed to support a farm from the production stage to the export stage, but the project was disorganized and other rival farms tended to be opposed to this project. Moreover, in some instances the farms supported by this project participated in dumping sales or low-cost export using subsidies.

Third, there is no alternative measure when a farm violates an export contract. Farmers often canceled contracts when domestic price of the commodity was higher than the contract-price, opting to sell the commodity in the domestic market. In these cases, however, there is no effective means to prevent farmers from violating their contracts.

Finally, as a part of the government’s agricultural EPP, the effects of the overseas marketing projects are unsatisfactory since the projects haven’t been implemented as accurately and elaborately as originally intended. Farms and exporters that participate in the overseas marketing program may have insufficient information such as that which regards to preferences and the income of local consumers as well, in addition to data on their own purchasing patterns.

Conclusion

Strategies for promoting export can be drawn as follows: First, with aggressive strategy, massive finances acquired from oil export are invested in constructing roads, railways, and distribution facilities for agricultural commodities to improve the export logistics. This measure can prevent decreasing foreign exchange rate caused by an accumulated amount of oil export and at the same time, suppress spreading inflation. Also, this measure can achieve the effect of improving the logistic infrastructure for export as well as domestic marketing. Meanwhile, in order to expand the export of high quality organic agricultural products to the markets with high income, airway transport should be utilized. Differences in transport costs with overland route can be partially supported by the central government, local government, or export promotion institutions. In the WTO, support for distribution expenses can be categorized as a permitted subsidy for developing countries.

Additionally, diversification strategy is to develop potential export prospective commodities with competitiveness by continuously expanding government expenditure in R&D for the agricultural sector. Especially, it is necessary to consider establishing an institution exclusively in charge of carrying out activities for promoting sales and collecting information on overseas agricultural markets, including trends of prices, supply and demand conditions, and consumer preferences. These activities are necessary to secure the existing major markets as well as to pioneer new emerging markets.

References

Kim, K. P. et al. A Study on the Agricultural Export Promotion Policy (in Korean), Korea Rural Economic Institute, 2015.

KITA, <www.kita.net>.

U.N. Comtrade, <www.uncomtrade.org>.

aT <www.kati.net>

Agricultural Export Promotion Policy in Korea

Introduction

With the passage of time, Korean exports of agricultural products have undergone many changes. During the 1950s and 1960s, major agricultural exports included rice, cocoons, ginseng and tobacco. In the 1970s, canned mushrooms, chestnuts, mushrooms, arrowroot wallpaper, and oriental medicine herbs emerged as new export items while rice exports decreased sharply. Since the 1980s, the export of fruits, vegetables (kimchi, bell peppers, cherry tomatoes, eggplants, etc.), processed foods, pork and floricultural products, along with Korean traditional products such as ginseng, tobacco and chestnuts, increased significantly leading to diversification of Korea’s export products.

Trends in Korean agricultural export

Korea’s agricultural export increased from US$1.59 billion in 2000 to US$6.11 billion in 2015. Export to the largest market, Japan, increased from US$0.7 billion to US$1.17 billion during the same period. The largest increase in agricultural export was export to China, which has been the second largest export market for Korean agriculture since 2008, surging from US$118 million to US$1,048 million in the same period. Export to the United States has increased from US$145 million in 2000 to US$628 million in 2015, and agricultural exports to other major markets such as Hong Kong, Vietnam, Russia, the United Arab Emirates, and Taiwan have also increased significantly.

Traditionally, Korean agricultural export has been heavily dependent on the Japanese market. The dependency ratio for the Japanese market, however, has significantly lowered from 46.2 % in 2000 to 19.2 % in 2015. On the other hand, the ratio for the Chinese market has increased from 7.8 % to 17.1 % during the same period. The dependency ratio for the U.S. market has been slightly lowered from 9.7 %to 10.2 % during the same period. Korean agricultural exports to Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern countries including Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, Afghanistan, and Iraq have increased by more than five times during the same period. These countries have become emerging markets for Korean agriculture.

Table 1. Korean agricultural export by country

Unit: US$ Million

2000

2005

2008

2010

2012

2015

World Total

1,509.1

2,221.5

3,048.2

4,114.6

5,341.1

6,107.3

Japan

697.1

713.3

752.5

1,184.1

1,591.4

1,168.1

China

117.6

231.2

349.1

523.3

785.3

1,048.1

United States

145.8

280.3

335.4

410.5

500.0

627.7

Hong Kong

134

123.7

162.7

220.2

258.3

347.7

Vietnam

8.8

17.3

55.7

125.5

256.8

293.6

Russia

74.2

203.8

286.3

214.5

234.3

129.8

United Arab Emirates

14.1

118

123

220.3

218.3

249.6

Taiwan

55.3

110.1

107

188.2

194.3

222.2

Indonesia

24.4

45.5

77

86.3

120.3

137.6

Philippines

29.7

27.8

48.7

89.8

101.2

115.7

Australia

15.9

40.1

72.1

79.0

96.8

110.7

Afghanistan

5.9

0.8

44.7

23.7

92.8

106.1

Singapore

18.2

21.8

33.3

81.8

87.6

100.2

Thailand

9.8

13.4

17.6

82.0

78.9

90.2

Malaysia

8.4

15.2

31.3

56.6

69.4

79.4

Canada

16.6

26.8

30.3

47.1

65.3

74.7

Mongolia

5.5

12.5

28

27.6

38.3

43.8

Iraq

-

1.2

106.5

114.9

73.7

34.5

Kazakhstan

4.3

8

27.4

25.5

34.6

32.5

Netherlands

7.6

6.6

62.5

16.1

23.7

25.7

Until 2000, none of the exporting commodities exceeded US$100 million in Korea. The top export product was ramen (US$95 million), followed by soju (US$88 million) and chestnuts (US$ 84 million). The export value of bakery products and kimchi was US$78 million.

In 2015, the export value of filter cigarettes was US$887 million, followed by mixed prepared food (US$1,063 million). The export value of coffee products was US$272 million and that of processed sugar was US$151 million. The number of agricultural commodities exceeding the export value of US$100 million was 13 in total. The export value of ginseng in particular, which are representative fresh agricultural products in Korea, exceeded US$100 million, respectively

Table 2. Korean agricultural export by commodity

Unit: US$ Million

2000

2005

2008

2010

2012

2015

Total

1,509.1

2,221.5

3,048.2

4,114.6

5,341.1

6,107.3

Processed food

Filter cigarettes

36.8

254.1

453.0

536.5

549.8

886.8

Mixed prepared food

1.4

1.2

152.4*

412.1

930.0

1,063.4

Coffee products

31.4

103.7

195.2

221.0

333.0

272.3

Processed sugar

71.6

94.0

127.7

242.1

291.2

151.4

Ramen

94.7

151.6

141.8

175.1

211.0

218.8

Beverages

11.6

36.5

64.4

102.6

184.1

293.6

Sauce

13.4

38.2

68.1

129.7

155.4

177.7

Bakery

79.0

110.8

142.4

110.3

131.5

149.9

Fermented beverages

prepared from cereals

18.0

9.1

33.4

97.1

137.9

12.9

Sugar, confectionery

76.6

82.1

94.6

100.2

134.2

153.5

Soju

87.9

116.2

124.1

123.1

114.3

87.8

Beer

19.0

38.1

43.3

46.8

65.4

84.5

Prepared, dry milk

3.5

9.3

24.0

24.4

36.2

41.4

Prepared grain food

14.0

31.7

25.0

45.3

58.6

67.0

Citrus (prepared or

preserved)

-

-

27.1

32.6

40.4

46.2

Feed

0.7

10.6

18.9

37.3

41.7

47.7

Pasta

11.5

21.0

28.4

29.0

13.8

15.8

Soybean meal

-

0.1

21.9

22.2

32.4

37.0

Gelatin

7.1

10.4

19.1

20.9

22.5

25.7

Noodles

9.7

13.5

24.4

27.6

34.1

39.0

Fresh agricultural products

Ginseng root

60.3

62.0

75.9

96.8

155.5

155.1

Kimchi

78.8

93.0

85.3

98.4

104.6

73.5

Paprika

-

53.1

54.2

58.3

65.9

85.2

Pear

17.1

56.1

47.3

54.1

47.3

58.4

Lily

4.3

10.5

19.1

27.8

33.1

9.3

Rose

10.3

10.4

11.8

34.2

25.7

3.3

Winter mushrooms

0.1

0.3

11.3

26.3

22.6

15.6

Apples

1.8

7.7

9.2

17.9

8.9

8.7

Chestnuts

84.1

35.0

23.6

12.6

10.2

11.7

Korean agricultural export promotion policies

Korean agricultural export promotion policies (EPP) can be categorized according to the branch of government that dictates the subject of the program: central government and local government. The central government usually implements agricultural EPPs through public organizations, such as the Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corporation (aT). The types of agricultural EPPs executed by the central government have been changing over time, and can now be sorted into five supporting programs related to producers opening markets abroad, organization production, export distribution, safety control, and monetary and insurance (Figure 1). Local governments, however, directly implements some EPP projects of their own, with policies related to education and consulting exports business, construction and managing export complexes, supporting the opening of markets abroad, and payment for export distribution costs and quality certifications.

Agricultural EPP of the Central Government

Support for organizing production

Backed by the central government, the aT supports production organization projects to secure stable quantities of agricultural products for export. Most farmers cannot meet the orders from buyers abroad due to their small-scale operations, thus, they need to coordinate with their peers in the industry before they can supply agricultural products for export. Increasing the output of numerous small and micro-scale farms can be possible only through a coordinated effort, and the following organizations have taken on the task: the Horticultural Production Complex, the Fostering Potential Export Products, the Human Resource Development Specialized in Export, the Export Leading Organization, and the Export Council Meeting. The government budget to support these projects has increased from KRW 117 million in 2000 to KRW3.04 billion in 2015.

Table 3. Korean agricultural EPP

Unit: KRW Million

2000

2005

2008

2009

2010

2012

2015

Support for organizing production

117

596

1,768

4,532

3,853

1,700

3,040

Project for supporting opening up overseas markets

8,075

11,467

15,106

18,681

22,737

29,490

32,100

Supporting export distribution projects

19,081

26,266

31,561

39,743

39,373

31,078

32,975

Safety Control

-

120

127

119

154

139

142

Monetary and insurance supporting policy

25,300

28,000

323,000

343,000

360,200

365,200

420,100

Figure 1. Korean agro-food export support System

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (2015)

Project to support opening of the overseas markets

An overview of projects and tasks aimed at supporting the opening of overseas markets includes sales promotion events with foreign distribution enterprises, participation in international food exhibitions, arranging buyer introductions, registering export brands in foreign countries, registering certification system abroad, and management for the government’s own agriculture brand "Whimori," among others.

Support for export distribution project

Export distribution support policies are designed to help logistics and sales promotions. Detailed sub-projects of the export distribution supporting policy contained in the Distribution Costs payment program, which the WTO’s agricultural agreements allow. In addition, Supporting Preservative Costs program and the Sharing Terminal Handling Charge program are also included in this area. The budget for supporting export distribution has increased from KRW 19.1 billion in 2000 to KRW 32.97 billion in 2015, which is the largest amount of subsidies in agricultural EPP projects. Their growth rate, however, is lower than that of any other project, which may imply that this kind of support is prohibited by the WTO and tends to be diminishing.

Support for safety control

The objective of the safety control support policy is to strengthen food safety. The Supporting Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) Certification Fee project and the Sharing Pesticide Test Fee project are included in this policy. The budget for safety control is almost stagnant, having been valued at KRW 142 million and KRW 139million in 2000 and 2015, respectively.

Monetary and insurance support policy

The purpose of the monetary and insurance support policy is to help farmers with poor access to finance and insurance participate in export insurance and operate capital loans. The Exchange Rate Insurance Fee and Export Insurance Premium projects are included in this area. Since this kind of support is a loan rather than a subsidy, the budget for this project is larger than that of other central government EPP projects in Korea, increasing from KRW 253 billion in 2000 to KRW 420.1 billion in 2015and accounting for 53.1 % of the total agricultural EPP budget.

Agricultural EPP of the local government

The purpose of agricultural EPPs initiated by local governments is to encourage the export of locally produced agricultural commodities and to increase the income of farmers. There are various kinds of EPPs at the local government level, such as education and consulting for export businesses, construction and management support for export complexes, support for the opening of overseas markets, support for the logistic costs for exporting, and support for quality certifications, etc. However, the budget is solely focused on supporting logistical costs for export distribution. The budget for this project increased from KRW 26.7 billion in 2007 to KRW 45.7 billion in 2013. Even though the share of the budget for this project was reduced from 76 % to 68 % during the same period, it still maintained over two-thirds of the budget for local government EPP.

Outcomes of the agricultural EPP and its limitations

One of the previous studies showed that 10 % increases in the government’s support for export logistic costs increased exports by 2.3 %. In addition, 10% increases in the government’s support infrastructure investments for export can raise export by 4.7 % in the long run. This result can be utilized as a guide to agricultural EPP in Korea: progressively expanding support for export infrastructure while gradually reducing support for export logistics in the medium- and long-term.

Agricultural EPP appeared to have effects on increasing production and expanding employment in the national economy. National expenditure for agricultural EPP which was KRW 2.5 trillion during 2008–2014, resulted in net increments of national production of KRW 4.5 trillion of national production and employment of 8,800 in three years. Meanwhile, there are some limitations to Korea’s agricultural EPP. First, even though the budget for supporting export logistical costs should be reduced due to the financial burdens of the government and negotiation trends concerning the WTO/DDA, there is no alternative measure. Since farmers and exporters want the government to continue to provide support in the future, it is inevitable that the disputes on this issue will persist.

Second, the performance of some projects, such as the Supporting Export Leading Organization, was negligible. This project aimed to support a farm from the production stage to the export stage, but the project was disorganized and other rival farms tended to be opposed to this project. Moreover, in some instances the farms supported by this project participated in dumping sales or low-cost export using subsidies.

Third, there is no alternative measure when a farm violates an export contract. Farmers often canceled contracts when domestic price of the commodity was higher than the contract-price, opting to sell the commodity in the domestic market. In these cases, however, there is no effective means to prevent farmers from violating their contracts.

Finally, as a part of the government’s agricultural EPP, the effects of the overseas marketing projects are unsatisfactory since the projects haven’t been implemented as accurately and elaborately as originally intended. Farms and exporters that participate in the overseas marketing program may have insufficient information such as that which regards to preferences and the income of local consumers as well, in addition to data on their own purchasing patterns.

Conclusion

Strategies for promoting export can be drawn as follows: First, with aggressive strategy, massive finances acquired from oil export are invested in constructing roads, railways, and distribution facilities for agricultural commodities to improve the export logistics. This measure can prevent decreasing foreign exchange rate caused by an accumulated amount of oil export and at the same time, suppress spreading inflation. Also, this measure can achieve the effect of improving the logistic infrastructure for export as well as domestic marketing. Meanwhile, in order to expand the export of high quality organic agricultural products to the markets with high income, airway transport should be utilized. Differences in transport costs with overland route can be partially supported by the central government, local government, or export promotion institutions. In the WTO, support for distribution expenses can be categorized as a permitted subsidy for developing countries.

Additionally, diversification strategy is to develop potential export prospective commodities with competitiveness by continuously expanding government expenditure in R&D for the agricultural sector. Especially, it is necessary to consider establishing an institution exclusively in charge of carrying out activities for promoting sales and collecting information on overseas agricultural markets, including trends of prices, supply and demand conditions, and consumer preferences. These activities are necessary to secure the existing major markets as well as to pioneer new emerging markets.

References

Kim, K. P. et al. A Study on the Agricultural Export Promotion Policy (in Korean), Korea Rural Economic Institute, 2015.

KITA, <www.kita.net>.

U.N. Comtrade, <www.uncomtrade.org>.

aT <www.kati.net>