1. Introduction

True to its title as the tree of life, coconut is considered as the lifeblood of Philippine agriculture. Next to rice, it is the country’s most important agricultural crop as evidenced by its significant contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) posted at 1.14%. It has played pertinent role in global competitiveness as the country’s primary agricultural export (Jadina, 2014). At 4% share to gross value added in agriculture (GVA), coconut ranked fourth next to major staple foods and banana. Despite its significant role in spurring growth in the economy, it is still regarded as an “orphan child” of Philippine agriculture (Quieta 2012) due to the dismal investment to the sector as compared to other crops.

Purportedly, the coconut industry should have been a well-funded sector, if not for the controversies and legal litigations surrounding the coconut levy fund[3] which was collected from the farmers through the enactment of various laws. The fund, estimated to be worth P74 billion (B) at the current market value (House Committee Meeting, 2015) was generated primarily to support the development of the coconut industry.

In the Supreme Court (SC)[4] ruling in January 24, 2012, the court upheld the decision of the Sandigangbayan[5] in 2004 to award 24% of the block shares of San Miguel Corporation (SMC), acquired through the coconut levy, in favor of the government for the benefit of the coconut farmers and the industry as a whole. While the said amount is only a portion of the contested total coconut levy funds, it served as the beginning to reap the benefits due to the coconut industry. It also brings to fore the importance of creating an enabling policy environment that would safeguard and establish a mechanism for the judicious utilization of the coconut levy funds.

This paper, divided into three parts, served as a review of the various policies enacted to establish the coconut levy funds administered from 1971-1982, a period under the Marcos regime. The first section provides a simple explanation of the economic implications of imposing levies or taxes in the coconut sector. The second part provides an overview of the status of the coconut industry in the country while the last section discusses the evolution of the coconut levy funds and the current plans and initiatives of the government to achieve the goals originally set in establishing the funds.

2. The Effects of Taxation or Levy Policies

This section provides a simple explanation of the implication of tax or levy policies in the coconut industry. The important role of the government in providing foundation for the environment where tax or levy policies operate is also highlighted. It serves as basis in the analysis of how the coconut levy in the Philippines was established.

Tax or levy system is primarily established to provide revenue for the government to finance essential expenditures on goods and services (Myles, 2009). For developing countries like the Philippines, tax provides the means to boost public expenditures on productivity-enhancing services such as infrastructure, research and development, public education and health care.

Levies, enacted through policies and regulations, are temporary taxes collected and state-enforced non-voluntary contributions which are purposively allocated to a sector. Unlike income taxes, levies are not reverted to the government to form part of the national funds for redistribution to the entire economy (Taylor, 2012 and Ramos, 2013). In this sense, levies are considered funds that is sectoral in nature.

However, while taxation and the related policies on it are viewed important in developing the coconut industry, a central concern on public finance is the inefficiency due to distortions created by taxation or levies imposed. Tax or levy imposed a two-pronged effect on coconut prices and quantity produced and demanded. Tax increases the price of commodity or good paid by the consumers while it reduces the amount received by the producers. At the same time because of taxes or levies, quantity produced and demanded is reduced.

Welfare loss is inevitable due to the innate inefficiencies caused by the imposition of the coconut levies. It has become disincentive to farmers since it adversely affected farm profitability (Aquino, 1993). As emphasized by Habito and Intal (1988), taxes on coconut products collected at any point along the marketing chain were borne by the farmers.

3. The Philippine Coconut Industry: Status, Issues and Challenges

Coconut is considered one of the Philippines’ most valuable agricultural commodity. In fact, it is regarded as the “tree of life” because of the numerous uses and services it can provide. It has significantly spurred the country’s economic growth with contribution of 4% to GVA in agriculture (BAS, 2013).

As an export winner, about 70% of the country’s coconut production is exported. The industry has been consistently in the top five major net foreign exchange earners which was estimated to have reached an annual average of PHP 32 B (PCA 2008 as cited by Quieta, 2012). In 2009-2011, the coconut industry contributed 30% (USD 1,290 million) of the total export earnings from agricultural products. Among the major coconut products exported include coconut oil (CNO), desiccated coconut (DCN), copra meal, and oleochemicals (Endaya and Noreno, 2006). The Philippines lead all other major CNO producing countries with an annual average production of 1.01 million mt in 2008-2010. During the same period, the country also dominated the export of DCN with an average annual export volume of 0.13 million mt (PCA, 2013).

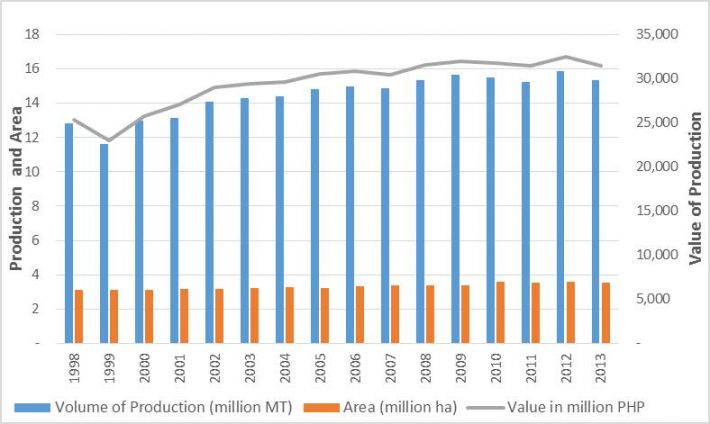

The coconut industry has long been one of the largest users of agricultural land and labor. It is planted in 3.55 million ha of land representing 26% of the total agricultural area in the country. The industry caters for about 2.60 million farms located in 68 provinces across the country (PCA, 2014). The vast area of coconut lands produces an annual average of 15 B nuts which places the country second in rank, next to Indonesia, among the top coconut producing countries in the world. However, in the last 15 years (1998-2013), growth in the sector was at dismal rate of 1.32% and 0.88% in terms of production and area, respectively (Fig. 1). This has resulted to poor annual average yield of only 46 nuts/tree.

Fig. 1. The Philippine coconut production, area and value of production, 1998-2013

While coconut provides endless possibilities, the 25 million farmers engaged in various coconut-based enterprises do not seem to fully realize its benefits and therefore remained poverty stricken. The latest NSCB (2014) survey on the average monthly poverty threshold indicated that a family of five requires a monthly income of PHP 8,778 to live above poverty. However, coconut farmers only earn PHP 50.00 a day or a dismal income of PHP 1,500.00 per month. It is no surprise that they are considered among the most impoverished. The Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES) in 2009 indicated that coconut farmers ranked second in terms of poverty incidence and ranked third in terms of subsistence poverty, a measure of extreme poverty or those who do not even have enough income to meet basic food needs. The food threshold indicated that an average monthly income of PHP 6,125.00 is needed for a family of five to eat and address basic nutritional requirements. Sadly, with the meager income, coconut farmers cannot even provide for basic food needs. Hence, hunger abounds among coconut families. In fact, the coconut regions are home to majority of the extremely poor Filipinos: Caraga (25.3%), Zamboanga Peninsula (23.5%), Eastern Visayas (19%) and Bicol (17.8%) (Reyes et al., 2012).

The dismal performance of the industry and the high poverty incidence among the coconut farmers is rooted in the myriad of issues. One of these is the low farm productivity (Aragon, 2000) of only 46 nuts/tree, a level way below the potential yield of more than 100 nuts/tree using science interventions and proper agricultural technologies (Industry Strategic S&T Plan (ISP) on Coconut of the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD), 2014).

Aragon (2000) further emphasized on the following productivity-related problems. About 25% of the coconut trees are senile having been planted for over 60 years, a level beyond the productive age of coconut. Farmers are still planting low-yielding coconut varieties and adopt poor agronomic management practices. The neglect of good agronomic practices is manifested by the poor soil nutrition and low fertility of coconut fields. In addition, occurrence of pests and diseases as well as natural calamities (e.g. typhoons, drought) have greatly affected the yield performance of coconut. Further, other pressing issues that threatens productivity are land conversion and unregulated and illegal cutting of coconut trees.

While various initiatives have developed high yielding coconut varieties, R&D has yet to establish technology for the fast and efficient mass propagation (e.g. coconut somatic embryogenesis technology) of these improved varieties (Interview PCAARRD-ISP Manager on Coconut, 2015). Quieta (2012) emphasized that aggressive R&D initiatives to diversify coconut products stayed at the backseat, hence a major challenge to the industry. Majority of the exported coconut products have remained in raw form such as crude coconut oil, copra meal, copra, DCN and young coconuts.

Inadequate infrastructure support, especially on postharvest facilities, is also considered a major issue. Another pertinent problem is the vulnerability of coconut to world price fluctuations. Most often, farmgate prices are very low due to low international market value. Supply chain related problems such as high transportation and handling cost as well as the presence of numerous middlemen along the chain are also notable in the coconut industry.

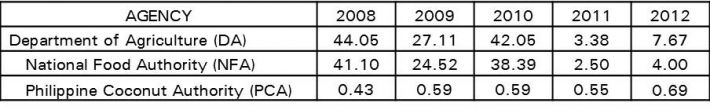

An important and an overarching cause of the coconut industry’s poor growth is the low allocation on research and development (R&D) which is an important source of technological innovation for the industry. Considering the sector’s contribution to the economy and its services to the majority of the poor Filipinos, it is ironic that it has been appropriated with limited funds from the government. In 2008-2012, the average yearly allocation for coconut, through the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) was PHP 0.58 B. This is an indication of the low priority given to the poor coconut farmers. In comparison, rice received an average budgetary support of PHP 22.10 B.

Table 1. National expenditure program of DA, NFA and PCA, in billion PHP, 2008-2012

4. The Evolution and Controversies of the Coconut Levy Policies in the Philippines

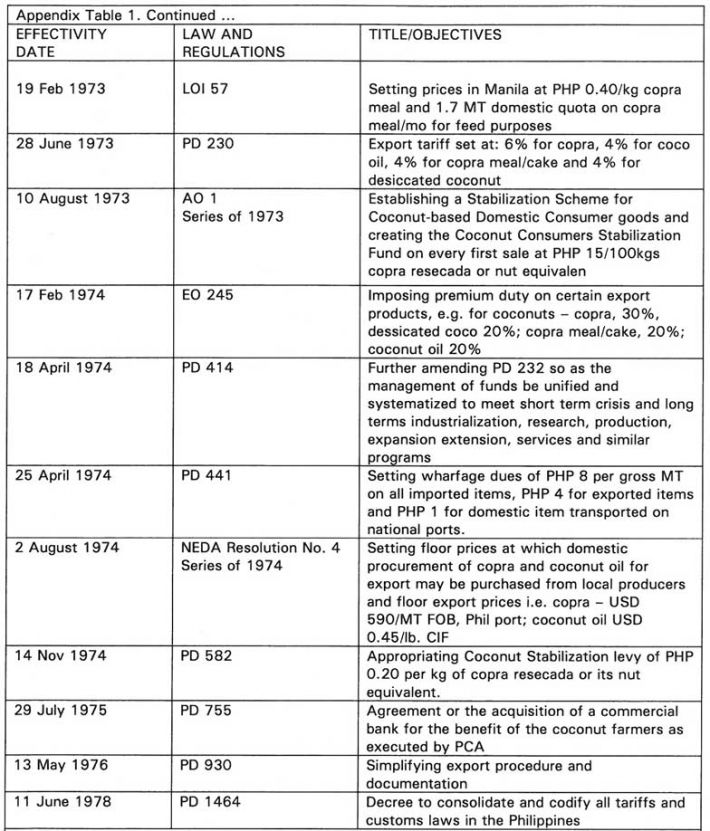

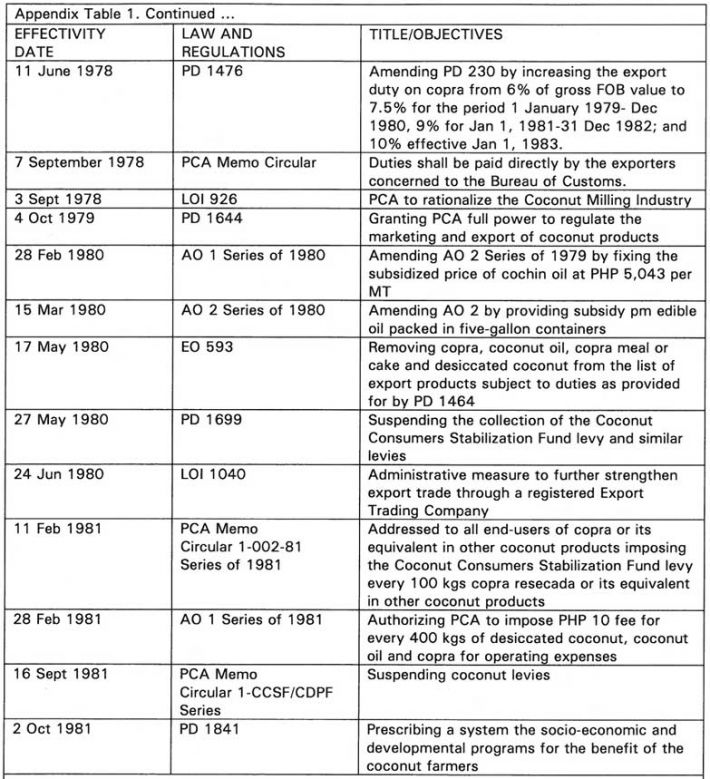

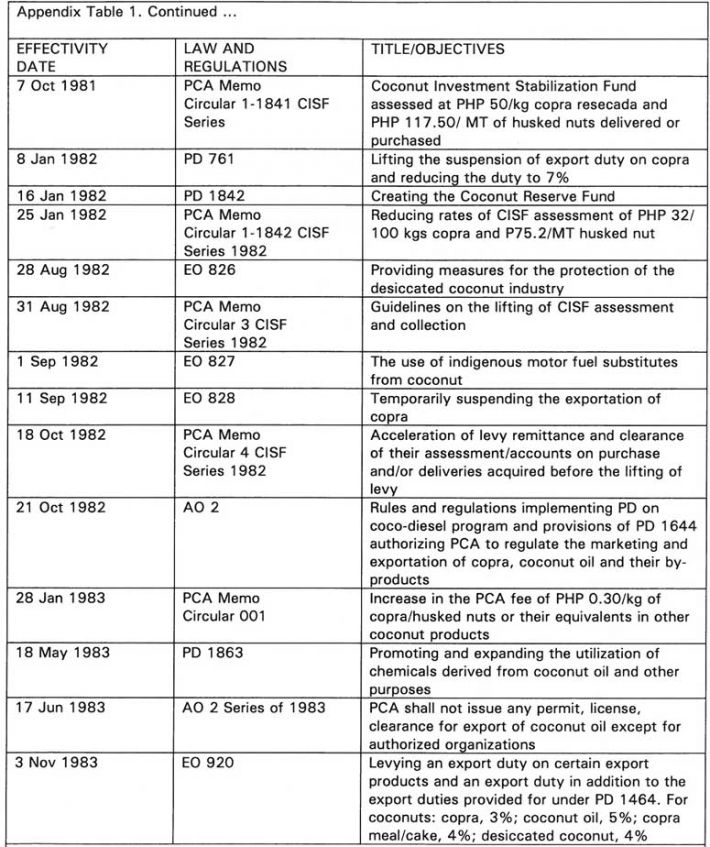

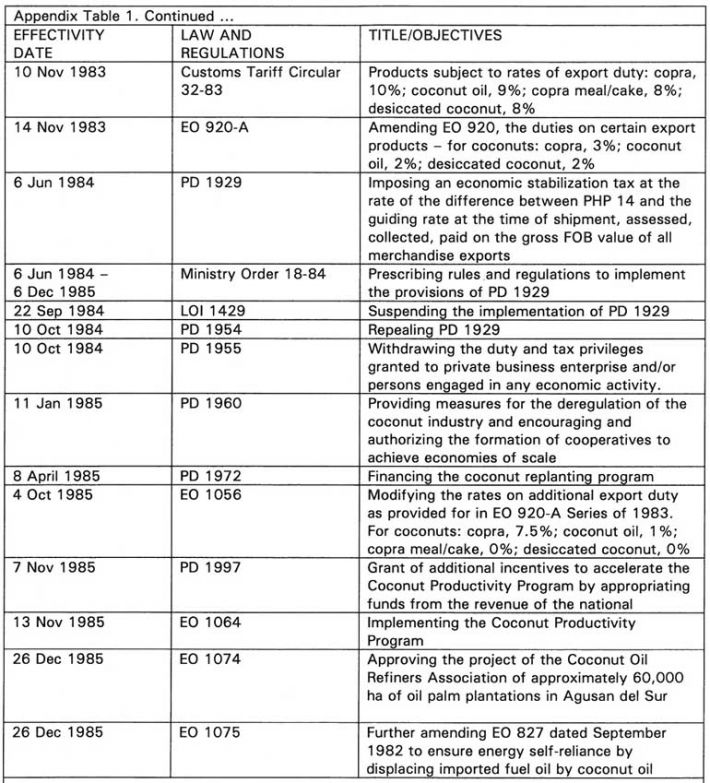

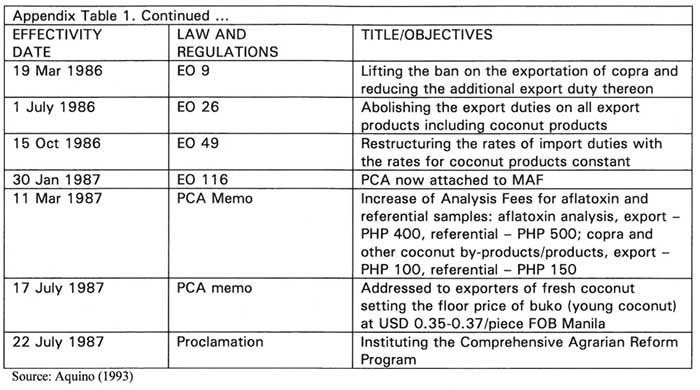

Since the early 1900, the government has created legal bases that provided an environment for the various policies affecting the coconut industry (Appendix Table 1). Among these policies, the major coconut levies enacted and implemented during the period 1970s up to early 1980s which was the period under the Marcos administration, were perhaps considered the most popular due to the controversies surrounding them.

The succeeding section provides discussion of the development and the evolution of the four major coconut levies in the Philippines: (1) Coconut Investment Fund (CIF); (2) Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF); (3) Coconut Industry Development Fund (CIDF); and (4) Coconut Industry Stabilization Fund (CISF) imposed during the Marcos regime and the policies that paved the way for their implementation.

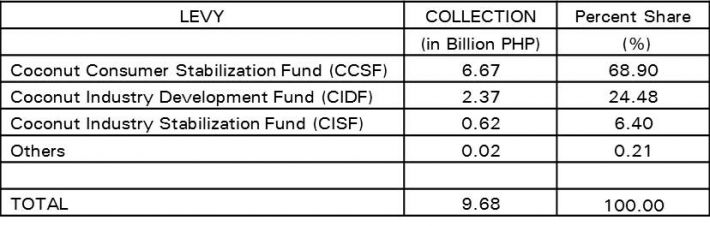

Table 2 shows the Commission on Audit’s (COA)[6] estimate of the total amount of levies collected during the Marcos administration. About PHP 9.68 B was generated from the coco levy funds, excluding those collection under CIF. Majority (69%) of the coco levies came from the imposition of the CCSF. Ramos (2013) reported that only about 33% of the P9.68 B was allocated to programs directly benefiting the farmers. The remaining 67% of the levies was used to invest in various enterprises, debt servicing, subsidies for coconut-based consumers and exporters, and as government donations.

Table 2. Coconut levies collected during the Marcos regime

Source: Commission on Audit (1997) as cited by Ramos (2013)

4.1 Coconut Investment Fund (CIF)

In pursuit of vertical integration[7] in the coconut industry, Republic Act (RA) 6260 otherwise known as “An Act Instituting a Coconut Investment Fund and Creating a Coconut Investment for the Administration Thereof” was enacted into law on June 19, 1971. RA 6260 that created the Coconut Investment Fund (CIF) is the only statute on coconut levy enacted by Congress.

Primarily, CIF was created to allow farmers to invest in the processing and trading of their products. It provided a medium- and long-term financing for capital investments in the coconut industry (Sadian, 2012). It instituted the collection of tax amounting to PHP 5.50 per mt of copra or any equivalent coconut products from coconut producers for a period of 10 years. CIF was used to underwrite the Coconut Investment Company (CIC) with capital requirement of PHP 100 million.

The levy under CIF was directly collected from copra users who, in turn, deducted this from the buying price of copra. This means that the prices received by farmers was the market price of copra at the farm less the levy. To establish ownership in the company, the farmers were issued COCOFUND receipts during the first sale of their products. The levy receipts served as proof for the shares of stock in the CIC (Clarete and Roumasset, 1983). As such, it should be pointed out that the government’s initial subscription to the CIC is “for and on behalf of the coconut farmers”.

4.2 Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF)

The most important production levy in the entire history of the coconut industry was the Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF), the first coconut-levy enacted during the Martial Law period. This fund turned out to be the source of the contested stream of rents acquired from the coconut levies. As indicated in the Commission on Audit (COA) report in 1997, CCSF comprised about 69% of the total coco levies accounted.

The legal background that supported the implementation of CCSF is presented in Appendix Table 2. Established on August 20, 1973 through the enactment of PD 276, CCSF was created to subsidize the sale of essential coconut-based products and promote for socialized prices of such products. CCSF was initiated to mitigate the effects of the dramatic increase of oil-based products due to the cooking oil crisis in 1973. A Stabilization Fund Levy of PHP 150 per mt of copra or its equivalent products was imposed but throughout its implementation, it peaked to PHP 1,000 per mt of copra or its equivalent products. For the period of CCSF implementation, levy rates varied with an annual average weighted rate between PHP 300-800 (Clarete and Roumasset, 1983 as cited by Ramos, 2013).

Originally proposed to be implemented for one year or after the cooking oil crisis is over, the collection of the CCSF levy was continued through the issuance of PD 414. Two additional uses of CCSF were included in the amendments: (1) to pay for about 90% of the premium duty collected from coconut exporters and (2) to provide funds for the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) to invest in processing plants, R&D and extension services.

CCSF was also crucial for the acquisition of the First Union Bank (FUB), now the United Coconut Planters Bank (UCPB). The possession of UCPB was legally based from the enactment of PD 755 in July 1975 which allowed for the approval of credit policy for the coconut industry. Under PD 755 a readily available credit facilities at preferential rates were granted to farmers through the implementation of the “Agreement for the Acquisition of a Commercial Bank for the benefits of the coconut farmers.” The UCPB was the principal instrument by which farmers could invest in processing and trading of their products. To emphasize, in view of achieving the objectives of vertical integration stipulated under RA 6260, PD 755 to acquire the UCPB, a commercial bank, was materialized.

4.3 Coconut Industry Development Fund (CIDF)

To achieve productivity in the sector, PD 582 creating the Coconut Industry Development Fund was passed into law in November 1974. CIDF was instrumental in launching the national coconut replanting program. The fund was created to establish, operate and maintain a hybrid coconut seednut farm to serve as the main source of planting materials for distribution, free of charge, to coconut farmers. It was through CIDF that the Agricultural Investors Incorporated (AII) became the sole supplier of seednuts to implement the national coconut replanting program.

Under CIDF, an initial capital requirement of PHP 100 million was generated from CCSF. A permanent levy of PHP 200 per mt of copra or its equivalent products was imposed.

4.4 Coconut Industry Stabilization Fund (CISF)

Upon resumption from suspension in May 27, 1980, the CCSF was renamed Coconut Development Project Fund (CDPF). CDPF provided for an export tax equivalent to PHP 1,000, a sum total of levy amounting to PHP 600 and additional PHP 400 for export clearance. In 1981, CCSF was again renamed to the Coconut Industry Stabilization Fund (CISF) through the enactment of PD 1841.

PD No. 1841 or the law “Prescribing a System of Financing the Socio-Economic and Developmental Program for the Benefit of the Coconut Farmers and Accordingly Amending the Laws Thereon” created the CISF. More than the technological intervention, CISF specifically addressed socio-economic and development programs that included scholarship programs, life and accident insurance and the coconut industry rationalization program for five years. CISF also supported the Coconut Reserve Fund (CRF) used to fund critical socio-economic and development programs.

5. Current Policy Initiatives Towards Achieving the Goals of the Coco Levy

Through the Presidential Commission on Good Governance (PCGG), created under former President Corazon C. Aquino, initiatives to recover the various assets and properties acquired using the coconut levies were conducted. A total of eight cases were filed in the Sandiganbayan which included among others the sequestration of the shares of stock in UCPB, in various Coconut Industry Investment Fund (CIIF) companies and in San Miguel Corporation.

To date, the coconut levy funds ballooned upto PHP 74 B, but various estimates on the total levy funds ranges from PHP 100 to PHP 150 B. While the initiatives have recovered significant amount of the coco levies, this remain unutilized by the sector it was created for. In view of this, the current government through the creation of a law aims to establish a mechanism for the expeditious release and judicious utilization of the coco levy funds.

Both the Senate and the House of Representatives crafted a number of bills to provide an enabling policy environment for the development of a mechanism to tap the huge resource pool offered by the coconut levy funds. The current Aquino Administration has also provided its pronouncement to support the just and prudent use of the funds through the approval of two Executive Orders (EO) on March 18, 2015. Committee meetings in the Congress as well as various consultation activities have been conducted to provide holistic view of all stakeholders’ concerns.

5.1 President Aquino’s Executive Orders

The current Aquino administration’s support to the judicious utilization of the coco levy fund is stipulated in the following pronouncements: (1) EO No. 179 or the EO “Providing the Administrative Guidelines for the Inventory and Privatization of Coco Levy Assets”; and (2) EO 180 or the EO “Providing the Administrative Guidelines for the Reconveyance and Utilization of Coco Levy Assets for the Benefit of the Coconut Farmers and the Development of the Coconut Industry, and for other Purposes.”

The orders indicate that the disposition and utilization of the recovered coconut levies shall be for the improvement of coconut farm productivity, developing coconut-based enterprises and increasing the income of coconut farmers. The funds shall also be used to strengthen farmers’ organizations and to achieve a balance, equitable, integrated and sustainable growth in the coconut sector. Specifically, EO 179 directs the PCGG to identify and account all known coconut levy assets within 60 days from the effectivity of the order. The inventory shall include specific assets sequestered by PCGG, ownership and share of stocks in all corporations or companies acquired through the coco levies, money, assets and investments of CIIF companies. Moreover, EO 179 allows for the privatization of the coco levy upon the recommendation of the PCGG after consultation and evaluation with the Department of Finance (DOF), the Office of the Presidential Assistant for Food Security and Agricultural Modernization (OPAFSAM) and the PCA.

The EO 180, on the other hand, provides for the preservation, protection and recovery of all coco levy assets to prevent dissipation or reduction in their value. The order recognizes the importance of establishing a roadmap that lay-out the plans to achieve development of the coconut industry.

5.2 Legislative Initiatives for the Utilization of the Coconut Levies

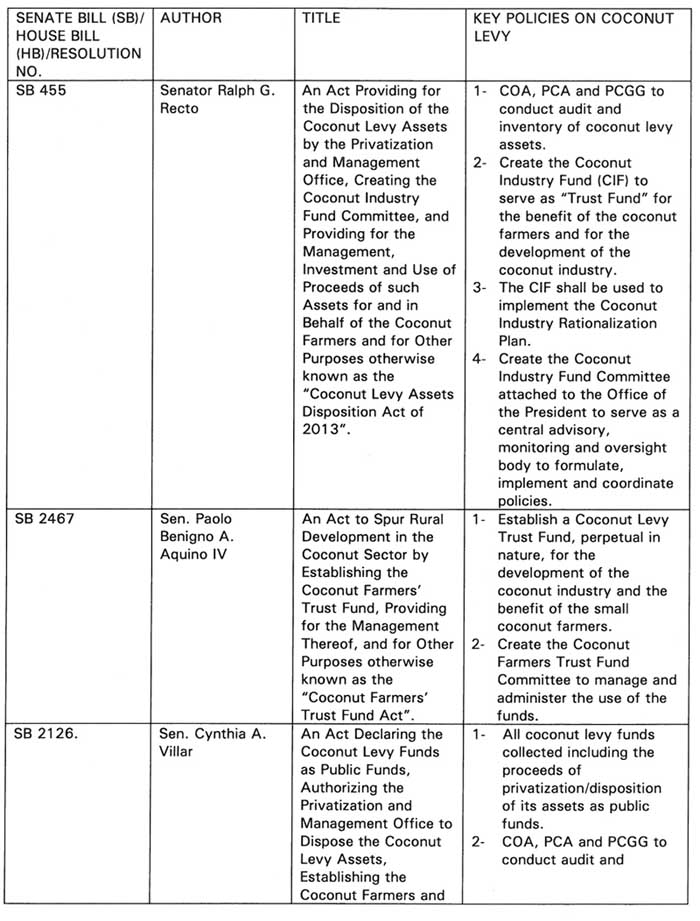

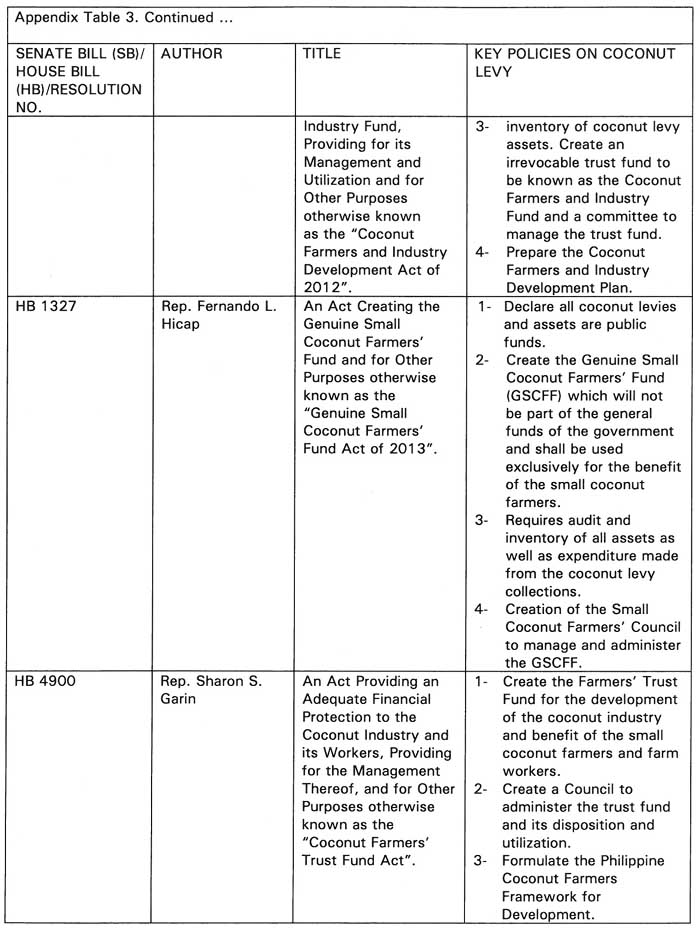

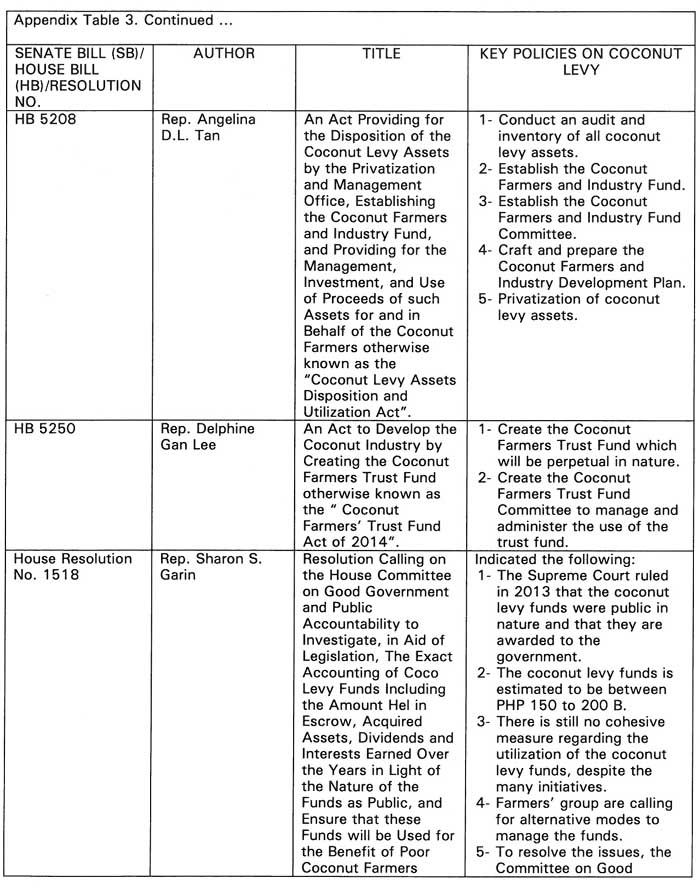

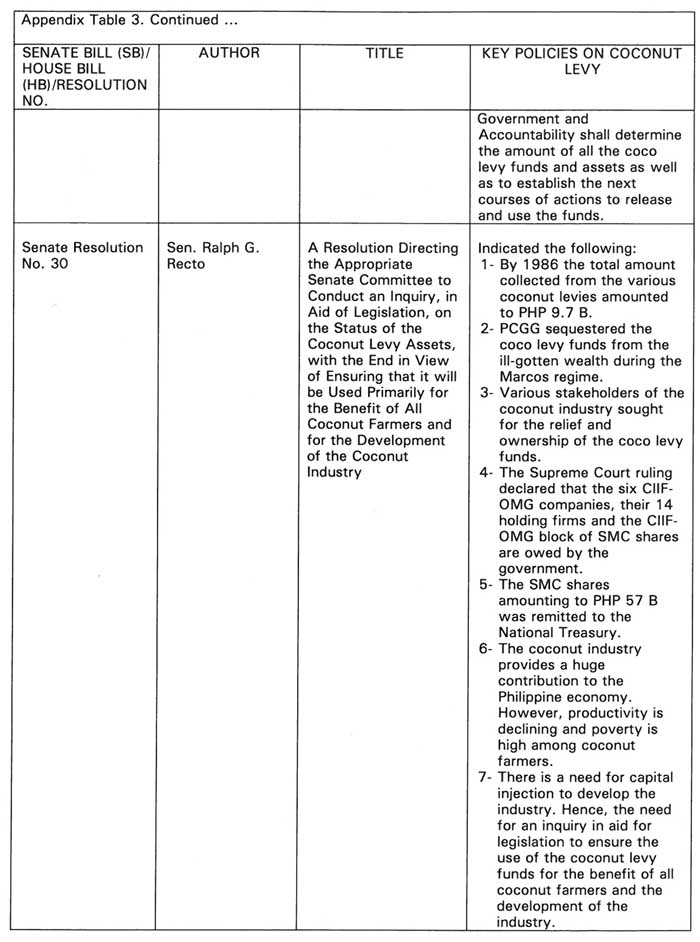

Support to the judicious and sustainable utilization of the collected coconut levy funds is manifested in the legislative policies proposed both in the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives. The bills aim to consolidate the benefits due to the coconut farmers, especially the poor and marginalized, and to expedite the delivery and attainment of a balanced, equitable, integrated and sustainable growth and development of the coconut industry. The salient provisions of the bills are presented in Appendix Table 3.

The coconut levy fund management mechanism provided under the various bills has four main features: (1) creation of a trust fund; (2) conduct of audit and inventory of all coconut levy funds and assets; (3) creation of the coconut farmers and industry fund committee or council; and (4) establishment of coconut industry plan or framework. The trust fund shall be established to help the coconut farmers and develop the coconut industry. Its initial capitalization shall be generated from all the current recovered coconut levy funds and shall thereafter be augmented with all the proceeds, income, interests, earnings and monetary benefits from the potential privatization or disposition of other coconut levy assets and investments. The trust fund shall be perpetual in character to ensure its sustainability.

The fund management mechanism also provides for the conduct of complete accounting and inventory of all the funds generated, assets and properties acquired, and all investments, disbursements and expenditures arising from the coconut levies. COA shall be the lead agency in the audit in coordination with the PCA and PCGG.

One of the important features of the policy initiatives is the recognition and inclusion of coconut farmers as one of the key decision-makers on the appropriate use and allocation of the coco levy funds. They will form part of the committee or council that will be established to manage and administer the coco levy funds including the disposition and utilization of its earnings. As the rightful owners of the coconut levy funds, farmers’ participation in the appropriation and utility of funds would ensure that they are part of and benefit from the growth in the sector.

Lastly, the bills provide for the crafting of the coconut industry plan or framework that will outline the national program to develop the industry. The development plan include among others program on enhancing productivity, rehabilitating and replanting activities since majority of the coconut trees are senile, R&D initiatives to develop science-based solutions to technological problems impeding the sector, improvement and integration of processing and marketing, and provision of infrastructures. The plan shall also include programs and activities that will directly benefit the coconut farmers such as but not limited to medical/health and life insurance services and educational plans or scholarships for students coming from families of coconut farmers.

6. Summary and Conclusion

The coconut industry is an important sector in the Philippine agriculture. It supports millions of Filipino farmers and workers and has been a significant contributor to the country’s economic growth. Efforts, through policies and laws, have been initiated to develop the coconut industry. These policies provided legal environment for the collection of tax or levies to serve as funds to be used for the growth of the sector. However, while the purpose of collecting the coconut levies is noble, issues on the utilization and management of the funds hindered the long-term objective of developing the coconut industry.

Currently, the coconut levy funds collected since the Marcos regime has been legally awarded to the government on behalf of the coconut farmers. Years of legal dispute to claim these funds have been settled.

With the resolution of some coconut levy fund cases, a mechanism of fund management and utilization that is viable, transparent and inclusive can effect sustainable development interventions for the sector. However, the decision on how the coconut levy funds will be used should be combined with a clear and implementable roadmap for the sector. This would ensure that investments on programs and projects will indeed achieve its goal of providing the necessary development of the coconut sector, thereby growth can be inclusive and felt by all stakeholders of the sector especially the farmers.

7. References

Abesamis, T. S. The coco levy injustice. Global Balita. Retrieved on March 16, 2015, from http://globalbalita.com/2011/05/01/the-coco-levy-injustice/

Aquino, A.P. 1993. The Effects of Tax Policy on the Level and Distribution of Benefits from Technological Change in the Philippine Coconut Industry. Master Thesis on Agricultural Economics, University of the Philippines Los Baños.

Aragon, C.T. 2000. Coconut Program Area Research Planning and Prioritization. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). Discussion Paper Series 2000-31. Retrieved January 21, 2015, from http://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/ris/dps/pidsdps0031.pdf

Auerbach, A.J. and Hines Jr. 2001.Taxation and Economic Efficiency. In: Handbook of Public Economics. Eds. Auerbach, A.J. and Feldstein. Retrieved June 15, 2015, from http://www.bus.umich.edu/otpr/Wp2001-7paper.pdf

Bakija, J. 2013. Social Welfare, Income Inequality, and Tax Progressivity: A Primer on Modern Economic Theory and Evidence. Williams College. Retrieved on January 21, 2015, from http://web.williams.edu/Economics/bakija/BakijaSocialWelfareIncomeInequalityAndTaxProgressivity.pdf

Clarete, R.L. and Roumasset, J.A. An Analysis of the Economic Policies Affecting the Philippine Coconut Industry. Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS). Discussion Paper 83-08. Retrieved February 11, 2015, from http://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/ris/wp/pidswp8308.pdf

Commission on Audit. Retrieved on June 15, 2015, from http://www.lawphil.net/administ/coa/coa.html

Endaya, S. & Noveno, M. 2006. Economic contributions of emerging coconut products. USAID. Retrieved from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADH618.pdf

Investopedia. Vertical Integration. Retrieved on June 15, 2015, from http://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/verticalintegration.asp

Leyte Samar Daily Express. Comments on the Coconut Industry Poverty Reduction Roadmap. Retrieved April 16, 2015, from http://www.nscb.gov.ph/ru8/NewsClip/2013/LSDE080713_Comments.pdf

Myles, G. D. (2009), “Economic Growth and the Role of Taxation-Theory”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 713, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/222800633678

Oniki, S. 1992. Philippine Coconut Industry and the International Trade. Master’s Research Paper. Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/10977/1/pb92on01.pdf

PinoyAko. People. Retrieved on June 15, 2015, from http://www.people.nfo.ph/business/businessman/eduardo-cojuangco-jr/

Philippine Statistics Authority-National Statistical Coordination Board. Poverty Statistics. Retrieved April 16, 2015, from http://www.nscb.gov.ph/poverty/

Quieta, J.P.S. Coco Levy Funds: A Fiscal Stimulus to the Coconut Industry? Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (CPBRD) Policy Brief. Retrieved February 11, 2015, from http://www.congress.gov.ph/cpbo/images/PDF%20Attachments/CPBRD%20Policy%20Brief/02-PB%20Coco%20Levy.pdf

Ramos, Charmaine G. 2013. The Power and the Peril: Producers Associations Seeking Rents in the Philippines and Colombia in the Twentieth Century. A Dissertation submitted to the Department of International Development of the London School of Economics, London, United Kingdom.

Reyes, C.M., Tabuga, A.D., Asis, R.D. and Datu, M.B.G. 2012. Poverty and Agriculture in the Philippines: Trends in Income Poverty and Distribution. PIDS Discussion Paper 2012-09.

Sadian, J.C.G.M. The Coco Levy Funds: Is the Shell Game Approaching Its End? The CenSei Report. Retrieved on February 11, 2015, from http://censeisolutions.com/uploaded/files/TCR%20Vol2%20No15.pdf

Sandiganbayan. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://sb.judiciary.gov.ph/about.html

Supreme Court of the Philippines. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/#

Taylor, Madeline. 2012. Is it a levy, or is it a tax, or both? Revenue Law Journal, 22 (1). Retrieved January 31, 2015, from http://epublications.bond.edu.au/rlj/vol22/iss1/7

The Supreme Court of the Philippines. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://www.chanrobles.com/supremecourtofthephilippines.htm

The Economist. Vertical Integration. Retrieved June 15, 2015, from http://www.economist.com/node/13396061

[1] Policy paper submitted to the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center (FFTC) for the project titled “Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy”. Policy papers, as corollary outputs of the project, describe pertinent Philippine laws and regulations on agriculture, aquatic and natural resources.

[2] Philippine Point Person to the FFTC Project on Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy and Senior Science Research Specialist and Chief Science Research Specialist, respectively, of the Socio-Economics Research Division-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (SERD-PCAARRD) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines.

[3] Coconut levy funds is also referred as coco levy in this paper.

[4] The Supreme Court of the Philippines (Filipino: Kataas-taasang Hukuman ng Pilipinas) is the highest court in the Philippines. The Philippine Constitution vests judicial power in one Supreme Court and such lower courts as may be established by law. (Section 1, Article VIII, 1987 Constitution). It is composed of one (1) Chief Justice and fourteen (14) Associate Justices.

[5] Sandiganbayan is a special court in the Philippines established through Presidential Decree No. 1606. It has jurisdiction over criminal and civil cases that involves graft and corrupt practices and such other offenses committed by public officers and employees, government-owned or controlled corporations (GOCCs), in relation to their office as may be determined by law. (Article XIII), 1973 Constitution.

[6] The Commission on Audit (COA) is the Philippines' Supreme State Audit Institution. It is a constitutional office tasks to audit all accounts pertaining to all government revenues and expenditures/uses of government resources and to prescribe accounting and auditing rules. It has exclusive authority to define the scope and techniques for its audits, and prohibits the legislation of any law which would limit its audit coverage (http://www.lawphil.net/administ/coa/coa.html, 2015).

[7] Vertical integration refers to the merging of businesses or enterprises that are engage at the different stages of production. Upstream producers usually integrate with the downstream distributers to secure market for their outputs or products (The Economist, 2015). It can reduce costs and improve efficiencies of companies/enterprises due to the associated decrease in transportation expenses and turnaround time (Investopedia, 2015). For the case of the coconut industry, the farmers who served as the primary suppliers of inputs (upstream) were involved in the processing, trading and distributing coconut products (downstream).

Appendix Table 1. Laws to develop the Philippine coconut industry, 1940-1987

Appendix Table 2. The legal background of the Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF), 1973-1982

.jpg)

.jpg)

Appendix Table 3. Legislative bills and resolutions establishing the mechanism for the utilization and disposition of the coconut levy funds

|

Date submitted: Jan. 25, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Jan. 28, 2016

|

The Long Climb towards Achieving the Promises Of the Tree OF Life: A Review of the Philippine Coconut Levy Fund Policies

1. Introduction

True to its title as the tree of life, coconut is considered as the lifeblood of Philippine agriculture. Next to rice, it is the country’s most important agricultural crop as evidenced by its significant contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) posted at 1.14%. It has played pertinent role in global competitiveness as the country’s primary agricultural export (Jadina, 2014). At 4% share to gross value added in agriculture (GVA), coconut ranked fourth next to major staple foods and banana. Despite its significant role in spurring growth in the economy, it is still regarded as an “orphan child” of Philippine agriculture (Quieta 2012) due to the dismal investment to the sector as compared to other crops.

Purportedly, the coconut industry should have been a well-funded sector, if not for the controversies and legal litigations surrounding the coconut levy fund[3] which was collected from the farmers through the enactment of various laws. The fund, estimated to be worth P74 billion (B) at the current market value (House Committee Meeting, 2015) was generated primarily to support the development of the coconut industry.

In the Supreme Court (SC)[4] ruling in January 24, 2012, the court upheld the decision of the Sandigangbayan[5] in 2004 to award 24% of the block shares of San Miguel Corporation (SMC), acquired through the coconut levy, in favor of the government for the benefit of the coconut farmers and the industry as a whole. While the said amount is only a portion of the contested total coconut levy funds, it served as the beginning to reap the benefits due to the coconut industry. It also brings to fore the importance of creating an enabling policy environment that would safeguard and establish a mechanism for the judicious utilization of the coconut levy funds.

This paper, divided into three parts, served as a review of the various policies enacted to establish the coconut levy funds administered from 1971-1982, a period under the Marcos regime. The first section provides a simple explanation of the economic implications of imposing levies or taxes in the coconut sector. The second part provides an overview of the status of the coconut industry in the country while the last section discusses the evolution of the coconut levy funds and the current plans and initiatives of the government to achieve the goals originally set in establishing the funds.

2. The Effects of Taxation or Levy Policies

This section provides a simple explanation of the implication of tax or levy policies in the coconut industry. The important role of the government in providing foundation for the environment where tax or levy policies operate is also highlighted. It serves as basis in the analysis of how the coconut levy in the Philippines was established.

Tax or levy system is primarily established to provide revenue for the government to finance essential expenditures on goods and services (Myles, 2009). For developing countries like the Philippines, tax provides the means to boost public expenditures on productivity-enhancing services such as infrastructure, research and development, public education and health care.

Levies, enacted through policies and regulations, are temporary taxes collected and state-enforced non-voluntary contributions which are purposively allocated to a sector. Unlike income taxes, levies are not reverted to the government to form part of the national funds for redistribution to the entire economy (Taylor, 2012 and Ramos, 2013). In this sense, levies are considered funds that is sectoral in nature.

However, while taxation and the related policies on it are viewed important in developing the coconut industry, a central concern on public finance is the inefficiency due to distortions created by taxation or levies imposed. Tax or levy imposed a two-pronged effect on coconut prices and quantity produced and demanded. Tax increases the price of commodity or good paid by the consumers while it reduces the amount received by the producers. At the same time because of taxes or levies, quantity produced and demanded is reduced.

Welfare loss is inevitable due to the innate inefficiencies caused by the imposition of the coconut levies. It has become disincentive to farmers since it adversely affected farm profitability (Aquino, 1993). As emphasized by Habito and Intal (1988), taxes on coconut products collected at any point along the marketing chain were borne by the farmers.

3. The Philippine Coconut Industry: Status, Issues and Challenges

Coconut is considered one of the Philippines’ most valuable agricultural commodity. In fact, it is regarded as the “tree of life” because of the numerous uses and services it can provide. It has significantly spurred the country’s economic growth with contribution of 4% to GVA in agriculture (BAS, 2013).

As an export winner, about 70% of the country’s coconut production is exported. The industry has been consistently in the top five major net foreign exchange earners which was estimated to have reached an annual average of PHP 32 B (PCA 2008 as cited by Quieta, 2012). In 2009-2011, the coconut industry contributed 30% (USD 1,290 million) of the total export earnings from agricultural products. Among the major coconut products exported include coconut oil (CNO), desiccated coconut (DCN), copra meal, and oleochemicals (Endaya and Noreno, 2006). The Philippines lead all other major CNO producing countries with an annual average production of 1.01 million mt in 2008-2010. During the same period, the country also dominated the export of DCN with an average annual export volume of 0.13 million mt (PCA, 2013).

The coconut industry has long been one of the largest users of agricultural land and labor. It is planted in 3.55 million ha of land representing 26% of the total agricultural area in the country. The industry caters for about 2.60 million farms located in 68 provinces across the country (PCA, 2014). The vast area of coconut lands produces an annual average of 15 B nuts which places the country second in rank, next to Indonesia, among the top coconut producing countries in the world. However, in the last 15 years (1998-2013), growth in the sector was at dismal rate of 1.32% and 0.88% in terms of production and area, respectively (Fig. 1). This has resulted to poor annual average yield of only 46 nuts/tree.

Fig. 1. The Philippine coconut production, area and value of production, 1998-2013

While coconut provides endless possibilities, the 25 million farmers engaged in various coconut-based enterprises do not seem to fully realize its benefits and therefore remained poverty stricken. The latest NSCB (2014) survey on the average monthly poverty threshold indicated that a family of five requires a monthly income of PHP 8,778 to live above poverty. However, coconut farmers only earn PHP 50.00 a day or a dismal income of PHP 1,500.00 per month. It is no surprise that they are considered among the most impoverished. The Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES) in 2009 indicated that coconut farmers ranked second in terms of poverty incidence and ranked third in terms of subsistence poverty, a measure of extreme poverty or those who do not even have enough income to meet basic food needs. The food threshold indicated that an average monthly income of PHP 6,125.00 is needed for a family of five to eat and address basic nutritional requirements. Sadly, with the meager income, coconut farmers cannot even provide for basic food needs. Hence, hunger abounds among coconut families. In fact, the coconut regions are home to majority of the extremely poor Filipinos: Caraga (25.3%), Zamboanga Peninsula (23.5%), Eastern Visayas (19%) and Bicol (17.8%) (Reyes et al., 2012).

The dismal performance of the industry and the high poverty incidence among the coconut farmers is rooted in the myriad of issues. One of these is the low farm productivity (Aragon, 2000) of only 46 nuts/tree, a level way below the potential yield of more than 100 nuts/tree using science interventions and proper agricultural technologies (Industry Strategic S&T Plan (ISP) on Coconut of the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD), 2014).

Aragon (2000) further emphasized on the following productivity-related problems. About 25% of the coconut trees are senile having been planted for over 60 years, a level beyond the productive age of coconut. Farmers are still planting low-yielding coconut varieties and adopt poor agronomic management practices. The neglect of good agronomic practices is manifested by the poor soil nutrition and low fertility of coconut fields. In addition, occurrence of pests and diseases as well as natural calamities (e.g. typhoons, drought) have greatly affected the yield performance of coconut. Further, other pressing issues that threatens productivity are land conversion and unregulated and illegal cutting of coconut trees.

While various initiatives have developed high yielding coconut varieties, R&D has yet to establish technology for the fast and efficient mass propagation (e.g. coconut somatic embryogenesis technology) of these improved varieties (Interview PCAARRD-ISP Manager on Coconut, 2015). Quieta (2012) emphasized that aggressive R&D initiatives to diversify coconut products stayed at the backseat, hence a major challenge to the industry. Majority of the exported coconut products have remained in raw form such as crude coconut oil, copra meal, copra, DCN and young coconuts.

Inadequate infrastructure support, especially on postharvest facilities, is also considered a major issue. Another pertinent problem is the vulnerability of coconut to world price fluctuations. Most often, farmgate prices are very low due to low international market value. Supply chain related problems such as high transportation and handling cost as well as the presence of numerous middlemen along the chain are also notable in the coconut industry.

An important and an overarching cause of the coconut industry’s poor growth is the low allocation on research and development (R&D) which is an important source of technological innovation for the industry. Considering the sector’s contribution to the economy and its services to the majority of the poor Filipinos, it is ironic that it has been appropriated with limited funds from the government. In 2008-2012, the average yearly allocation for coconut, through the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) was PHP 0.58 B. This is an indication of the low priority given to the poor coconut farmers. In comparison, rice received an average budgetary support of PHP 22.10 B.

Table 1. National expenditure program of DA, NFA and PCA, in billion PHP, 2008-2012

4. The Evolution and Controversies of the Coconut Levy Policies in the Philippines

Since the early 1900, the government has created legal bases that provided an environment for the various policies affecting the coconut industry (Appendix Table 1). Among these policies, the major coconut levies enacted and implemented during the period 1970s up to early 1980s which was the period under the Marcos administration, were perhaps considered the most popular due to the controversies surrounding them.

The succeeding section provides discussion of the development and the evolution of the four major coconut levies in the Philippines: (1) Coconut Investment Fund (CIF); (2) Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF); (3) Coconut Industry Development Fund (CIDF); and (4) Coconut Industry Stabilization Fund (CISF) imposed during the Marcos regime and the policies that paved the way for their implementation.

Table 2 shows the Commission on Audit’s (COA)[6] estimate of the total amount of levies collected during the Marcos administration. About PHP 9.68 B was generated from the coco levy funds, excluding those collection under CIF. Majority (69%) of the coco levies came from the imposition of the CCSF. Ramos (2013) reported that only about 33% of the P9.68 B was allocated to programs directly benefiting the farmers. The remaining 67% of the levies was used to invest in various enterprises, debt servicing, subsidies for coconut-based consumers and exporters, and as government donations.

Table 2. Coconut levies collected during the Marcos regime

Source: Commission on Audit (1997) as cited by Ramos (2013)

4.1 Coconut Investment Fund (CIF)

In pursuit of vertical integration[7] in the coconut industry, Republic Act (RA) 6260 otherwise known as “An Act Instituting a Coconut Investment Fund and Creating a Coconut Investment for the Administration Thereof” was enacted into law on June 19, 1971. RA 6260 that created the Coconut Investment Fund (CIF) is the only statute on coconut levy enacted by Congress.

Primarily, CIF was created to allow farmers to invest in the processing and trading of their products. It provided a medium- and long-term financing for capital investments in the coconut industry (Sadian, 2012). It instituted the collection of tax amounting to PHP 5.50 per mt of copra or any equivalent coconut products from coconut producers for a period of 10 years. CIF was used to underwrite the Coconut Investment Company (CIC) with capital requirement of PHP 100 million.

The levy under CIF was directly collected from copra users who, in turn, deducted this from the buying price of copra. This means that the prices received by farmers was the market price of copra at the farm less the levy. To establish ownership in the company, the farmers were issued COCOFUND receipts during the first sale of their products. The levy receipts served as proof for the shares of stock in the CIC (Clarete and Roumasset, 1983). As such, it should be pointed out that the government’s initial subscription to the CIC is “for and on behalf of the coconut farmers”.

4.2 Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF)

The most important production levy in the entire history of the coconut industry was the Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF), the first coconut-levy enacted during the Martial Law period. This fund turned out to be the source of the contested stream of rents acquired from the coconut levies. As indicated in the Commission on Audit (COA) report in 1997, CCSF comprised about 69% of the total coco levies accounted.

The legal background that supported the implementation of CCSF is presented in Appendix Table 2. Established on August 20, 1973 through the enactment of PD 276, CCSF was created to subsidize the sale of essential coconut-based products and promote for socialized prices of such products. CCSF was initiated to mitigate the effects of the dramatic increase of oil-based products due to the cooking oil crisis in 1973. A Stabilization Fund Levy of PHP 150 per mt of copra or its equivalent products was imposed but throughout its implementation, it peaked to PHP 1,000 per mt of copra or its equivalent products. For the period of CCSF implementation, levy rates varied with an annual average weighted rate between PHP 300-800 (Clarete and Roumasset, 1983 as cited by Ramos, 2013).

Originally proposed to be implemented for one year or after the cooking oil crisis is over, the collection of the CCSF levy was continued through the issuance of PD 414. Two additional uses of CCSF were included in the amendments: (1) to pay for about 90% of the premium duty collected from coconut exporters and (2) to provide funds for the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) to invest in processing plants, R&D and extension services.

CCSF was also crucial for the acquisition of the First Union Bank (FUB), now the United Coconut Planters Bank (UCPB). The possession of UCPB was legally based from the enactment of PD 755 in July 1975 which allowed for the approval of credit policy for the coconut industry. Under PD 755 a readily available credit facilities at preferential rates were granted to farmers through the implementation of the “Agreement for the Acquisition of a Commercial Bank for the benefits of the coconut farmers.” The UCPB was the principal instrument by which farmers could invest in processing and trading of their products. To emphasize, in view of achieving the objectives of vertical integration stipulated under RA 6260, PD 755 to acquire the UCPB, a commercial bank, was materialized.

4.3 Coconut Industry Development Fund (CIDF)

To achieve productivity in the sector, PD 582 creating the Coconut Industry Development Fund was passed into law in November 1974. CIDF was instrumental in launching the national coconut replanting program. The fund was created to establish, operate and maintain a hybrid coconut seednut farm to serve as the main source of planting materials for distribution, free of charge, to coconut farmers. It was through CIDF that the Agricultural Investors Incorporated (AII) became the sole supplier of seednuts to implement the national coconut replanting program.

Under CIDF, an initial capital requirement of PHP 100 million was generated from CCSF. A permanent levy of PHP 200 per mt of copra or its equivalent products was imposed.

4.4 Coconut Industry Stabilization Fund (CISF)

Upon resumption from suspension in May 27, 1980, the CCSF was renamed Coconut Development Project Fund (CDPF). CDPF provided for an export tax equivalent to PHP 1,000, a sum total of levy amounting to PHP 600 and additional PHP 400 for export clearance. In 1981, CCSF was again renamed to the Coconut Industry Stabilization Fund (CISF) through the enactment of PD 1841.

PD No. 1841 or the law “Prescribing a System of Financing the Socio-Economic and Developmental Program for the Benefit of the Coconut Farmers and Accordingly Amending the Laws Thereon” created the CISF. More than the technological intervention, CISF specifically addressed socio-economic and development programs that included scholarship programs, life and accident insurance and the coconut industry rationalization program for five years. CISF also supported the Coconut Reserve Fund (CRF) used to fund critical socio-economic and development programs.

5. Current Policy Initiatives Towards Achieving the Goals of the Coco Levy

Through the Presidential Commission on Good Governance (PCGG), created under former President Corazon C. Aquino, initiatives to recover the various assets and properties acquired using the coconut levies were conducted. A total of eight cases were filed in the Sandiganbayan which included among others the sequestration of the shares of stock in UCPB, in various Coconut Industry Investment Fund (CIIF) companies and in San Miguel Corporation.

To date, the coconut levy funds ballooned upto PHP 74 B, but various estimates on the total levy funds ranges from PHP 100 to PHP 150 B. While the initiatives have recovered significant amount of the coco levies, this remain unutilized by the sector it was created for. In view of this, the current government through the creation of a law aims to establish a mechanism for the expeditious release and judicious utilization of the coco levy funds.

Both the Senate and the House of Representatives crafted a number of bills to provide an enabling policy environment for the development of a mechanism to tap the huge resource pool offered by the coconut levy funds. The current Aquino Administration has also provided its pronouncement to support the just and prudent use of the funds through the approval of two Executive Orders (EO) on March 18, 2015. Committee meetings in the Congress as well as various consultation activities have been conducted to provide holistic view of all stakeholders’ concerns.

5.1 President Aquino’s Executive Orders

The current Aquino administration’s support to the judicious utilization of the coco levy fund is stipulated in the following pronouncements: (1) EO No. 179 or the EO “Providing the Administrative Guidelines for the Inventory and Privatization of Coco Levy Assets”; and (2) EO 180 or the EO “Providing the Administrative Guidelines for the Reconveyance and Utilization of Coco Levy Assets for the Benefit of the Coconut Farmers and the Development of the Coconut Industry, and for other Purposes.”

The orders indicate that the disposition and utilization of the recovered coconut levies shall be for the improvement of coconut farm productivity, developing coconut-based enterprises and increasing the income of coconut farmers. The funds shall also be used to strengthen farmers’ organizations and to achieve a balance, equitable, integrated and sustainable growth in the coconut sector. Specifically, EO 179 directs the PCGG to identify and account all known coconut levy assets within 60 days from the effectivity of the order. The inventory shall include specific assets sequestered by PCGG, ownership and share of stocks in all corporations or companies acquired through the coco levies, money, assets and investments of CIIF companies. Moreover, EO 179 allows for the privatization of the coco levy upon the recommendation of the PCGG after consultation and evaluation with the Department of Finance (DOF), the Office of the Presidential Assistant for Food Security and Agricultural Modernization (OPAFSAM) and the PCA.

The EO 180, on the other hand, provides for the preservation, protection and recovery of all coco levy assets to prevent dissipation or reduction in their value. The order recognizes the importance of establishing a roadmap that lay-out the plans to achieve development of the coconut industry.

5.2 Legislative Initiatives for the Utilization of the Coconut Levies

Support to the judicious and sustainable utilization of the collected coconut levy funds is manifested in the legislative policies proposed both in the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives. The bills aim to consolidate the benefits due to the coconut farmers, especially the poor and marginalized, and to expedite the delivery and attainment of a balanced, equitable, integrated and sustainable growth and development of the coconut industry. The salient provisions of the bills are presented in Appendix Table 3.

The coconut levy fund management mechanism provided under the various bills has four main features: (1) creation of a trust fund; (2) conduct of audit and inventory of all coconut levy funds and assets; (3) creation of the coconut farmers and industry fund committee or council; and (4) establishment of coconut industry plan or framework. The trust fund shall be established to help the coconut farmers and develop the coconut industry. Its initial capitalization shall be generated from all the current recovered coconut levy funds and shall thereafter be augmented with all the proceeds, income, interests, earnings and monetary benefits from the potential privatization or disposition of other coconut levy assets and investments. The trust fund shall be perpetual in character to ensure its sustainability.

The fund management mechanism also provides for the conduct of complete accounting and inventory of all the funds generated, assets and properties acquired, and all investments, disbursements and expenditures arising from the coconut levies. COA shall be the lead agency in the audit in coordination with the PCA and PCGG.

One of the important features of the policy initiatives is the recognition and inclusion of coconut farmers as one of the key decision-makers on the appropriate use and allocation of the coco levy funds. They will form part of the committee or council that will be established to manage and administer the coco levy funds including the disposition and utilization of its earnings. As the rightful owners of the coconut levy funds, farmers’ participation in the appropriation and utility of funds would ensure that they are part of and benefit from the growth in the sector.

Lastly, the bills provide for the crafting of the coconut industry plan or framework that will outline the national program to develop the industry. The development plan include among others program on enhancing productivity, rehabilitating and replanting activities since majority of the coconut trees are senile, R&D initiatives to develop science-based solutions to technological problems impeding the sector, improvement and integration of processing and marketing, and provision of infrastructures. The plan shall also include programs and activities that will directly benefit the coconut farmers such as but not limited to medical/health and life insurance services and educational plans or scholarships for students coming from families of coconut farmers.

6. Summary and Conclusion

The coconut industry is an important sector in the Philippine agriculture. It supports millions of Filipino farmers and workers and has been a significant contributor to the country’s economic growth. Efforts, through policies and laws, have been initiated to develop the coconut industry. These policies provided legal environment for the collection of tax or levies to serve as funds to be used for the growth of the sector. However, while the purpose of collecting the coconut levies is noble, issues on the utilization and management of the funds hindered the long-term objective of developing the coconut industry.

Currently, the coconut levy funds collected since the Marcos regime has been legally awarded to the government on behalf of the coconut farmers. Years of legal dispute to claim these funds have been settled.

With the resolution of some coconut levy fund cases, a mechanism of fund management and utilization that is viable, transparent and inclusive can effect sustainable development interventions for the sector. However, the decision on how the coconut levy funds will be used should be combined with a clear and implementable roadmap for the sector. This would ensure that investments on programs and projects will indeed achieve its goal of providing the necessary development of the coconut sector, thereby growth can be inclusive and felt by all stakeholders of the sector especially the farmers.

7. References

Abesamis, T. S. The coco levy injustice. Global Balita. Retrieved on March 16, 2015, from http://globalbalita.com/2011/05/01/the-coco-levy-injustice/

Aquino, A.P. 1993. The Effects of Tax Policy on the Level and Distribution of Benefits from Technological Change in the Philippine Coconut Industry. Master Thesis on Agricultural Economics, University of the Philippines Los Baños.

Aragon, C.T. 2000. Coconut Program Area Research Planning and Prioritization. Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). Discussion Paper Series 2000-31. Retrieved January 21, 2015, from http://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/ris/dps/pidsdps0031.pdf

Auerbach, A.J. and Hines Jr. 2001.Taxation and Economic Efficiency. In: Handbook of Public Economics. Eds. Auerbach, A.J. and Feldstein. Retrieved June 15, 2015, from http://www.bus.umich.edu/otpr/Wp2001-7paper.pdf

Bakija, J. 2013. Social Welfare, Income Inequality, and Tax Progressivity: A Primer on Modern Economic Theory and Evidence. Williams College. Retrieved on January 21, 2015, from http://web.williams.edu/Economics/bakija/BakijaSocialWelfareIncomeInequalityAndTaxProgressivity.pdf

Clarete, R.L. and Roumasset, J.A. An Analysis of the Economic Policies Affecting the Philippine Coconut Industry. Philippine Institute of Development Studies (PIDS). Discussion Paper 83-08. Retrieved February 11, 2015, from http://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/ris/wp/pidswp8308.pdf

Commission on Audit. Retrieved on June 15, 2015, from http://www.lawphil.net/administ/coa/coa.html

Endaya, S. & Noveno, M. 2006. Economic contributions of emerging coconut products. USAID. Retrieved from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADH618.pdf

Investopedia. Vertical Integration. Retrieved on June 15, 2015, from http://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/verticalintegration.asp

Leyte Samar Daily Express. Comments on the Coconut Industry Poverty Reduction Roadmap. Retrieved April 16, 2015, from http://www.nscb.gov.ph/ru8/NewsClip/2013/LSDE080713_Comments.pdf

Myles, G. D. (2009), “Economic Growth and the Role of Taxation-Theory”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 713, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/222800633678

Oniki, S. 1992. Philippine Coconut Industry and the International Trade. Master’s Research Paper. Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/10977/1/pb92on01.pdf

PinoyAko. People. Retrieved on June 15, 2015, from http://www.people.nfo.ph/business/businessman/eduardo-cojuangco-jr/

Philippine Statistics Authority-National Statistical Coordination Board. Poverty Statistics. Retrieved April 16, 2015, from http://www.nscb.gov.ph/poverty/

Quieta, J.P.S. Coco Levy Funds: A Fiscal Stimulus to the Coconut Industry? Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (CPBRD) Policy Brief. Retrieved February 11, 2015, from http://www.congress.gov.ph/cpbo/images/PDF%20Attachments/CPBRD%20Policy%20Brief/02-PB%20Coco%20Levy.pdf

Ramos, Charmaine G. 2013. The Power and the Peril: Producers Associations Seeking Rents in the Philippines and Colombia in the Twentieth Century. A Dissertation submitted to the Department of International Development of the London School of Economics, London, United Kingdom.

Reyes, C.M., Tabuga, A.D., Asis, R.D. and Datu, M.B.G. 2012. Poverty and Agriculture in the Philippines: Trends in Income Poverty and Distribution. PIDS Discussion Paper 2012-09.

Sadian, J.C.G.M. The Coco Levy Funds: Is the Shell Game Approaching Its End? The CenSei Report. Retrieved on February 11, 2015, from http://censeisolutions.com/uploaded/files/TCR%20Vol2%20No15.pdf

Sandiganbayan. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://sb.judiciary.gov.ph/about.html

Supreme Court of the Philippines. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/#

Taylor, Madeline. 2012. Is it a levy, or is it a tax, or both? Revenue Law Journal, 22 (1). Retrieved January 31, 2015, from http://epublications.bond.edu.au/rlj/vol22/iss1/7

The Supreme Court of the Philippines. Retrieved April 1, 2015, from http://www.chanrobles.com/supremecourtofthephilippines.htm

The Economist. Vertical Integration. Retrieved June 15, 2015, from http://www.economist.com/node/13396061

[1] Policy paper submitted to the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center (FFTC) for the project titled “Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy”. Policy papers, as corollary outputs of the project, describe pertinent Philippine laws and regulations on agriculture, aquatic and natural resources.

[2] Philippine Point Person to the FFTC Project on Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy and Senior Science Research Specialist and Chief Science Research Specialist, respectively, of the Socio-Economics Research Division-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (SERD-PCAARRD) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines.

[3] Coconut levy funds is also referred as coco levy in this paper.

[4] The Supreme Court of the Philippines (Filipino: Kataas-taasang Hukuman ng Pilipinas) is the highest court in the Philippines. The Philippine Constitution vests judicial power in one Supreme Court and such lower courts as may be established by law. (Section 1, Article VIII, 1987 Constitution). It is composed of one (1) Chief Justice and fourteen (14) Associate Justices.

[5] Sandiganbayan is a special court in the Philippines established through Presidential Decree No. 1606. It has jurisdiction over criminal and civil cases that involves graft and corrupt practices and such other offenses committed by public officers and employees, government-owned or controlled corporations (GOCCs), in relation to their office as may be determined by law. (Article XIII), 1973 Constitution.

[6] The Commission on Audit (COA) is the Philippines' Supreme State Audit Institution. It is a constitutional office tasks to audit all accounts pertaining to all government revenues and expenditures/uses of government resources and to prescribe accounting and auditing rules. It has exclusive authority to define the scope and techniques for its audits, and prohibits the legislation of any law which would limit its audit coverage (http://www.lawphil.net/administ/coa/coa.html, 2015).

[7] Vertical integration refers to the merging of businesses or enterprises that are engage at the different stages of production. Upstream producers usually integrate with the downstream distributers to secure market for their outputs or products (The Economist, 2015). It can reduce costs and improve efficiencies of companies/enterprises due to the associated decrease in transportation expenses and turnaround time (Investopedia, 2015). For the case of the coconut industry, the farmers who served as the primary suppliers of inputs (upstream) were involved in the processing, trading and distributing coconut products (downstream).

Appendix Table 1. Laws to develop the Philippine coconut industry, 1940-1987

Appendix Table 2. The legal background of the Coconut Consumer Stabilization Fund (CCSF), 1973-1982

Appendix Table 3. Legislative bills and resolutions establishing the mechanism for the utilization and disposition of the coconut levy funds

Date submitted: Jan. 25, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Jan. 28, 2016