Shunsuke Yanagimura1

1Resaeach Faculty of Agriculture,

Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

e-mail: yngmr@agecon.agr.hokudai.ac.jp

ABSTRACT

One of the most serious problems Japanese agriculture have is the shortage of the number of farm business entities. The government has intended to secure farm business entities through some policies, which can be divided to the ‘farm’ related policy and the ‘farmer’ related policy. The first one called ‘farm business policy’ is promoting agricultural restructure through farm expansion and rise up of business performance. The government hopes to improve basic conditions of farm business organization and increase the number of young farmers as a result of agricultural restructure. The second one, the ‘farmer’ related policy, intends to increase the number of young farmers directly by financial support, targeting new entrants without the background of farm family. The government started the loan program in 1995 and reinforced the ‘farmer’ related policy by introducing income support in 2000s. Today the amount of financial support to a beginning farmer from the Japanese government is the highest in the world and such combination between the ‘farm’ related policy and the ‘farmer’ related policy seems effective from the point of view of the flow economy.

On the other hand, a new problem of how to transfer farm assets is rising to the surface as farm expansion is realized. This is recognized as the matter with the stock economy and how to establish farm ownership by the re-joint of ‘farm’ and ‘farmer’. In Hokkaido agriculture, well known for a large and business oriented farming, has faced such transfer issues since decades ago. Local organizations have tried to realize farm transfer to new entrants through various support programs.

Keywords: Farm business policy, Aging of farmers’ population, Farm expansion, Support for beginning farmers, Farm business transfer

INTRODUCTION

The most important issue the land-use type agriculture in Japan faces today is the retention of farm business entities. This issue has gained increasing attention from the Japanese government. Since the 1990s it has become particularly relevant to fundamental changes in agricultural conditions, such as the agricultural policy reform before and after the foundation of the World Trade Organization, and the increasing number of Japanese farmers reaching retirement as the following.

According to the Census of Agriculture, the population of farmers engaged mainly in farming decreased from 4,128 thousand in 1980 to 2,051 thousand in 2010, and the proportion of 65 years old and over to all of them rose from 27.8% up to 74.3% during the same period. The average age is 66.1 years old in 2010 and the decreasing and aging of farmers’ population has caused the decline of Japanese agriculture shown in table 1.

.jpg)

Within this paper I will examine policies aimed at maintaining farm business entities and related policies from the two sides of the farm business; ‘farm’ and ‘farmer’. The first side regards a farm as a business organization and involves maintaining the farm business entity through the solution of structural problems such as small farm size and low profitability. The second side is that regarding farmers engaged in the farm business, and the issues associated with how to increase the number of new entrants into agriculture.

It seems appropriate to connect the rejuvenation of farmers’ population with agricultural restructure, because the rejuvenation can be a good opportunity to change social structure and solve problems in general. I will consider the above by tracing the trend of agricultural policy and local activities for supporting beginning farmers in Hokkaido, and show some points we should think of.

TREND OF AGRICULTURAL POLICY FOR SECURING YOUNG FARMERS

Promotion of establishing farm business

In Japan, a new policy framework called ‘farm business policy’, as a part of agricultural policy reform characterized by market orientation, has been established to promote farm expansion by farmland accumulation and stabilize farm income since 1992. Although there have been some amendments to this policy such as the start of direct payment in the 2000s, it remains largely unchanged today. Priority has been given to the measures aimed at the establishment of ‘efficient and stable farm businesses’. Further, as large numbers of farmers began to retire, it has been recognized as an opportunity to accelerate structural change rather than a cause of an anxiety about the shortage of the population of farmers.

The government has also paid attention to the ‘farmer’ side issue. In 1995 a loan program targeting young people entering agriculture started. This program still plays an important part in the ‘farmer’ related policies. The beginning farmer centers were set up in all of prefectures to manage the loan program. This center works as a window office to accept and advise people wishing to enter the agricultural sector. The Basic Law on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas was enacted in 1999 and the article 25 titled “secure and foster talented farmers” amongst other things was placed in it, and the support policies for beginning farmers have been reinforced legally.

However, the government has had much concern about the ‘farm’ side issue and recognized that the establishment of farm business through structural change were required as a basic condition to increase the number of new entrants into farming.

The government’s 1992 policy, promoting farm land accumulation and stabilizing farm incomes, highlights the apparent trend. The goal of 1992 policy was to establish farm business operating a certain number of acreage of farmland in about ten years. In case of a family farm growing rice, the model was cultivating 10-20 hectares, which enabled a farmer to work 1,800-2,000 hours per year and earn $2.0 million -$2.5 million within a lifetime. The hours and income were equivalent to the conditions of workers engaged in other industries.

Moreover, the direct payment policy, started in 2007, requested community based farms organized by many small farmers to establish “efficient and stable farm business” to receive income support from the government, and stipulated setting the goal of income of an operator mainly in farming, in addition to other conditions such as acreage of farmland of 20 hectares and more, unified accounting as a sole business organization, and setting a plan to incorporate. Although the working hour condition has been eliminated, the government still intends to increase the number of young farmers through establishing ‘farms’ that can realize a target income. Further, this policy is widely accepted by the rural population.

Is farm business policy effective on securing farmers?

It is appropriate to assume that the establishment of farm business realizes a target income and enables to increase the number of new entrants into farming. However, the goal of the policy of securing ‘farmers’ can be accomplished only by such a farm business policy to establish farm business?

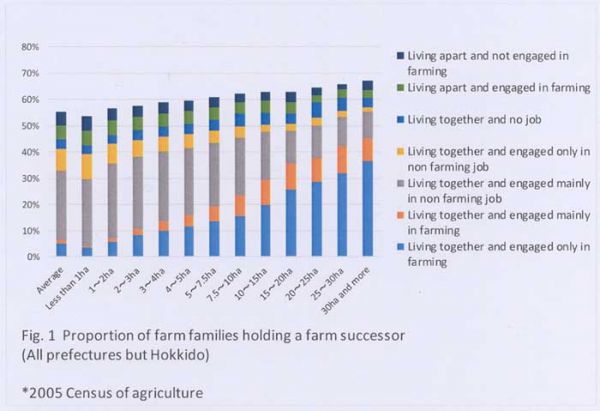

Fig. 1 shows the proportion of farm families holding a farm successor. This shows that, as farmland acreage increases so does the percentage of farm families holding a farm successor. However, the difference is not large. 67% of farm families of 30 hectares or more have successors while 54% of farm families of less than one hectare have successors. The difference increases if successors are regarded as all those living with the farm owners and those only engaged in farming or mainly engaged in farming. When this limited farm successor definition is applied, just 4% of farms of less than one hectare have successors and 45% of farms of 30 hectares or more. Yet the rate of farm families with successors still does not reach 50% even in case of those operating large farmland. Evidence suggests farm establishment influences new entrants’ behavior into farming, yet it does not secure enough entrants.

To fully understand this issue, we need to examine the followings:

-

Does farm business establishment realize income targets?

Despite the accumulation of farmland, incomes may not necessarily increase proportionally. This is because farm incomes are influenced by a variety of factors.

2. Do enough people want to enter farming?

Even if income targets are realized and not enough people want to become farmers, new entrants cannot be secured. This is supply side matter of new farmers.

Effect of income support for beginning farmers

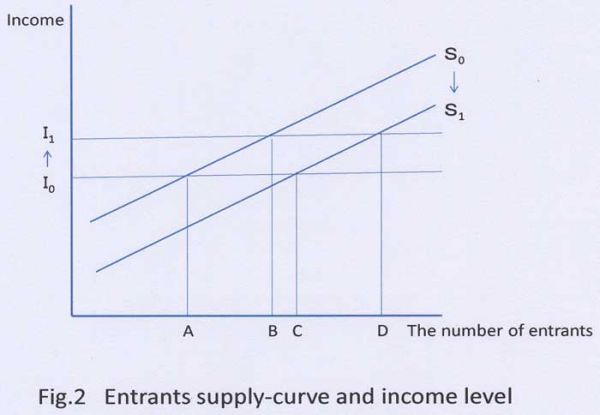

Agricultural policies to support beginning farmers started in 1995 with no interest loan program. More than a decade later, in 2008, agricultural employment promotion started. In 2012, a subsidy program was established to assist a new generation of farmers entering agriculture by the payment of $15,000 per year in 7 years at the longest to a beginning farmer. Polices for new entrants were systematically improved and the level of policy support has been upgraded. Although the policy initiatives may be a little late coming, the separation of ‘farmer’ focused policy from farm business policy seems to be a positive development. Fig. 2 examines the above by using the supply curve of new entrants. When the new entrants supply curve is S0 and income level is I0, and the number of new entrants is set at A. If farm business establishment is realized and income level goes up to I1, the number of new entrants increases from A to B. Moreover, if the supply curve shifts to S1 from S0 by income support while income level is the same, the number of new entrants will be set at C. Furthermore, the number of new entrants increases to D when there is a simultaneous improvement in income level and support.

DIFFICULTY TO RE-JOINT ‘FARM’ AND ‘FARMER’

The previously discussed issue reveals the flow economy of farm business and indicates that the number of new entrants into farming is influenced by income levels. Another issue involving farm stock and its economic impact exists. Transferring farms to new entrants isn’t easy, particularly as the size and associated assets of the farm increases. Farm assets can be divided into tangible and intangible assets. The following section discusses the difficulties associated with the transfer of each asset class.

Following the 1990s, policies to encourage young generation to enter agriculture has been developed. Recently measures to provide income support to beginning farmers were established. In the economic flow of farms, farm expansion leads to an increase in new agricultural entrants, while in the stock economy of farms, asset transfer is problematic, particularly with farm expansion. Farm asset transfer is a common problem in developed countries[1]. Issues around the intergenerational transfer of farm assets are beginning to surface in Japan. This issue focuses attention on the next generation of farm ownership and explores the issue regarding how to re-joint the ‘farm’ and the ‘farmer’.

Japanese farm families are facing difficulties in farm asset transfers by traditional farm succession practices and more suitable methods for intergenerational transfer are required even in case of a farm family with a successor. For example, some large farms have transferred assets by using the same measures as business succession planning for small companies in other industries. Further, some livestock farms use a venture capital funded by the government and the group of agricultural cooperatives to transfer farm assets.

Moreover, changing relationships and family dynamics are beginning to cause increasingly difficult farm transfers. Traditionally family farms are characterized by an extended family, where two or three generations live together on the farm and there is a sole inheritor. A sole inheritance custom used be connected with maintaining farming and farm family including care for old parents. Increasingly many issues are emerging around farm succession. Examples include:

-

A successor with no spouse

-

A successor living apart from their parents

-

A successor’s spouse working in a non-agricultural industry

-

A farmer’s wife who is engaged in farming following child rearing

-

Claims for divided succession.

In particular, claims for divided succession are gaining strength, challenging the traditional custom of sole inheritance. Improved family communications and methods for amicable and fair family agreements are required to ensure smooth farm business succession.

Farm asset transfer in the case of non-related parties is more difficult than in the case of the transfer from parents to children. However, as Fig. 1 shows, only small portion of farm families has secured successors devoted to farming. This trend also includes farm families of 30 hectares and more. The transfer of farm assets to new entrants, that do not have a background in farm family, is becoming a significant issue for Japanese land-use agriculture.

NEW ENTRANCE INTO HOKKAIDO AGRICULTURE

Farm transfer as a part of major issues Hokkaido agriculture faces

Hokkaido agriculture is well known for the history of the agricultural development since the late 19th century and its different characteristics such as large shares of products of dairy farming and crop farming growing potato, wheat, beans and sugar beet like western countries, and relatively large and business oriented farms devoted into farming without any other job and business. It’s quite different from other prefectures in Japan where many farmers are part-time ones or elder generation operating rice farming with small paddy field.

Hokkaido agriculture is the most productive part in Japanese agriculture but it has faced such problem of farm asset transfer from early time. In 2005, only 24.6% of farm families in Hokkaido, while 55.4% in other prefectures, had successors, although in Hokkaido the percentage of farm successors only or mainly engaged in farming is much higher than other prefectures. Because not all family farms can be transferred successfully, the Hokkaido prefectural government, local governments, JA (Japanese Agricultural Cooperative) and the Hokkaido Agricultural Development Corporation have begun to support new farm entrants. In the past 10 years between 2006 and 2013, 5,162 people have entered agriculture, with 609 (11.8%) not being the family farm successor. The beginning farmers without a farm family background are an indispensable part of new entrants in Hokkaido agriculture. And total number of new entrants without farm family background during the same period is 17,480, and the proportion of such entrants into Hokkaido agriculture is 3.5%.

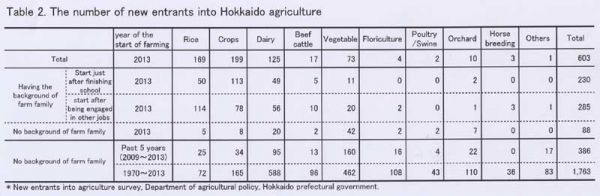

Table 2 shows the number of new entrants into Hokkaido agriculture and those without farm family background from the point of type of farming. According to this, new entrants without farm family background used to be the largest in dairy farming but the most popular type in past 5 years is vegetable.

As farm businesses in Hokkaido are comparatively large and many farmers wish to sell assets, such as farmland, when they quit or retire, new entrants are forced to find large sums of money to finance farm purchases. Moreover, the acquisition of intangible assets, including high level farm business management and production technology knowledge and skills, is necessary for beginning farmers. This reduces the risk of early financial failure and ensures the financial stability of the farm.

Various supports for beginning farmers

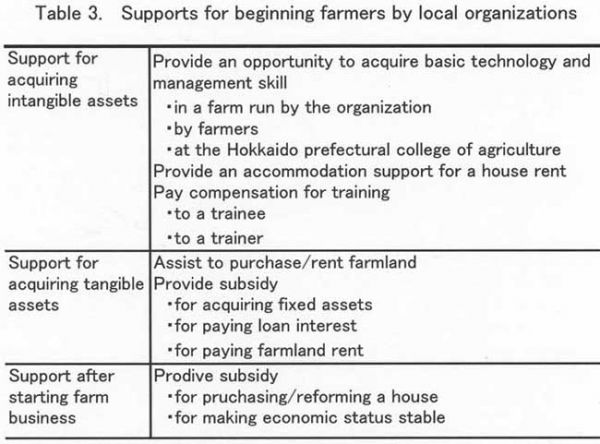

Table 3 shows the various measures taken to help solve the difficulties beginning farmers face, which include supports for acquiring tangible and intangible assets, and continue after the start of farming. They covers issues widely from farm business and tax to living conditions. Support program is arranged differently depending upon the type of farm business operation. This is influenced by which type of farm and a new entrant candidate a support organization chooses to accept and back[2].

A key difference amongst types of entry to agriculture is size of farm assets (Table 4). Greenhouse cultivation growing vegetables and flowers are examples of small farm assets. Fixed assets are comparatively small and the initial investment in this asset class can be low. Alternatively, land-use agriculture generally has large assets. This is particularly true for dairy farming, which typically includes a barn with a variety of facilities and vast forage fields.

However, asset costs can be reduced by contract farming and leasing farmland and machinery. Some new entrants to land-use agriculture have established small asset based farms by leasing land where farmland prices are high.

Another key difference to divide types of new entry is the standardization of farm businesses. Financial risks can be reduced by standardizing various aspects of farming. This includes providing production supplies, technology, sales of products, financing and business management. Further, risks to new entrants can be diminished by helping the beginning farmer reach and maintain these standard practices. The standardization of greenhouse cultivation is easier than other types of farming.

Some agricultural cooperatives in the dairy farming area have attempted to standardize dairy farm entry and thus hopefully reduce financial risks by establishing an educational farm for trainees to provide basic technology and skills to beginning farmers, and by setting up experiment farms for beginning farmers to manage actual dairy farming and spinning them out after making sure that their management become stable. The Hokkaido Agriculture Development Corporation (HADC) has offered a farm lease system to assist the transfer of farm assets. In many cases, local organizations have new entrants start farming by using HADC program after two to three years training on a farm or facility to them. Thus, the process from the acceptance of new entrants to the start of farming has been standardized.

On the other hand, many types of farming cannot be standardized. Diversified farms, growing several crops or livestock are difficult to be standardized. In diversified farming areas, it seems difficult to accept new entrants but recently some areas have started a support program in order to maintain the population of famers and agricultural resources.

As initial investment increases in size so does financial risk. Financial support for the acquisition of tangible assets is required to reduce such a risk. Due to the comparatively small initial investment required, and the accompanying smaller risks, greenhouse cultivation and lease type farming do not require large amounts of economic support.

Generally, a standardized farm with large assets, which is typically a dairy farm, requires local government or agricultural cooperative support. This type of farm is noted in Table 3, case B. Because of the large amount of support required for dairying, the number of new entrants who can receive support is necessarily small. In contrast, a farm that is not standardized and has small assets (case C in Table 4) requires little support. Therefore, it becomes possible to increase the number of new entrants. In such a case, there are many new entrants with various wishes for farming or living in country side, but their businesses are not always successful and the entrance and exit is repeated frequently as a result.

Moreover, the risk of failure can be reduced most effectively for standardized farms with small assets (case A). Greenhouse cultivation is a typical example of this type. On the other hand, farms that are not standardized and have large assets (Case D) face the largest risk of collapse. To reduce the financial risks associated with farm succession for non-related entrants, careful consideration of this transaction is needed. A strong and durable relationship over several years needs to be built between the farm owner and the successor so that both tangible and intangible assets are transferred. In the town of Bifuka, some dairy farm owners who did not have children who were able to be farm successors built an organization to promote farm succession to non-related entrants.[3]

A variety of schemes, in different areas of Hokkaido, attempt to solve the difficult problems faced in transferring farm assets to beginning farmers. Although the establishment of support mechanisms for beginning farmers requires time and effort, these initiatives help re-joint a ‘farm’ and a ‘farmer’ and establish farm ownership. This greatly not only assists new entrants to agriculture and but also benefits the revitalization of land use agriculture.

CONCLUSION

When the government started farm business policy in 1990s, how to restructure small farms was focused on in order to increase new entrants into agriculture. On the other hand, a new problem of farm transfer has been appeared and the nature of this problem is an excess of farm assets for new entrants.

It’s necessary to realize a certain level of farm size to get enough farm income, but it’s difficult to have farm assets, both tangible asset and intangible asset, in a short period for new entrants without farm family background.

To solve the problem of an excess of farm assets, farm assets should be divided into small pieces and transferred to several farmers or the process of farm transfer must be extended so that farm assets can be taken over gradually. We have to consider the system to realize such farm transfer and also how to get enough income from small piece of farm asset. Eventually, it’s important to establish a business model which is fit for new entrants and a method to reach it.

A dairy farming in Hokkaido is a typical farm business with large assets. Over $1 million is required as an initial investment for new entrance and a farm transfer has been becoming quite difficult.

Recently many new entrants are interested in intensive grazing with comparatively low investment and small number of cows, and they are thinking of the way of farm business to get income by raising up the income ratio to total sale. This is a good example of an action toward establishing a business model for new entrants.

REFERENCES

Hokkaido Agricultural Development Corporation (HADC) and Hokkaido Regional Agriculture Research Institute (HRARI). 2012. Securing farm business entities and the conditions of their settlement; cases of new entrants.

Sakai, J., S. Yanagimura, F. Ito and K. Saito. 1998. Succession and Entrance to Agriculture. Rural Culture Association, Tokyo, Japan.

Yanagimura, S., Y. Yamauchi and K. Higashiyama. 2012. Risk Reduction and Characteristics of Farm Transfer to Non-related Parties, Japanese Journal of Farm Management, 50(1): 16-26.

[1] Sakai et al. (1998) discussed the problem of intergenerational farm transfer in Japan compared with the USA and the European countries.

[2] HADC and HRARI (2012) shows many cases of new entrance into Hokkaido agriculture without farm family background.

[3] Yanagimura et al. (2012) analyzed the function of this organization.

|

Submitted as a country paper for the FFTC-RDA International Seminar on Enhanced Entry of Young Generation into Farming, Oct. 20-24, Jeonju, Korea |

Farm Expansion and Entry to Farm: Experiences in Hokkaido

Shunsuke Yanagimura1

1Resaeach Faculty of Agriculture,

Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

e-mail: yngmr@agecon.agr.hokudai.ac.jp

ABSTRACT

One of the most serious problems Japanese agriculture have is the shortage of the number of farm business entities. The government has intended to secure farm business entities through some policies, which can be divided to the ‘farm’ related policy and the ‘farmer’ related policy. The first one called ‘farm business policy’ is promoting agricultural restructure through farm expansion and rise up of business performance. The government hopes to improve basic conditions of farm business organization and increase the number of young farmers as a result of agricultural restructure. The second one, the ‘farmer’ related policy, intends to increase the number of young farmers directly by financial support, targeting new entrants without the background of farm family. The government started the loan program in 1995 and reinforced the ‘farmer’ related policy by introducing income support in 2000s. Today the amount of financial support to a beginning farmer from the Japanese government is the highest in the world and such combination between the ‘farm’ related policy and the ‘farmer’ related policy seems effective from the point of view of the flow economy.

On the other hand, a new problem of how to transfer farm assets is rising to the surface as farm expansion is realized. This is recognized as the matter with the stock economy and how to establish farm ownership by the re-joint of ‘farm’ and ‘farmer’. In Hokkaido agriculture, well known for a large and business oriented farming, has faced such transfer issues since decades ago. Local organizations have tried to realize farm transfer to new entrants through various support programs.

Keywords: Farm business policy, Aging of farmers’ population, Farm expansion, Support for beginning farmers, Farm business transfer

INTRODUCTION

The most important issue the land-use type agriculture in Japan faces today is the retention of farm business entities. This issue has gained increasing attention from the Japanese government. Since the 1990s it has become particularly relevant to fundamental changes in agricultural conditions, such as the agricultural policy reform before and after the foundation of the World Trade Organization, and the increasing number of Japanese farmers reaching retirement as the following.

According to the Census of Agriculture, the population of farmers engaged mainly in farming decreased from 4,128 thousand in 1980 to 2,051 thousand in 2010, and the proportion of 65 years old and over to all of them rose from 27.8% up to 74.3% during the same period. The average age is 66.1 years old in 2010 and the decreasing and aging of farmers’ population has caused the decline of Japanese agriculture shown in table 1.

Within this paper I will examine policies aimed at maintaining farm business entities and related policies from the two sides of the farm business; ‘farm’ and ‘farmer’. The first side regards a farm as a business organization and involves maintaining the farm business entity through the solution of structural problems such as small farm size and low profitability. The second side is that regarding farmers engaged in the farm business, and the issues associated with how to increase the number of new entrants into agriculture.

It seems appropriate to connect the rejuvenation of farmers’ population with agricultural restructure, because the rejuvenation can be a good opportunity to change social structure and solve problems in general. I will consider the above by tracing the trend of agricultural policy and local activities for supporting beginning farmers in Hokkaido, and show some points we should think of.

TREND OF AGRICULTURAL POLICY FOR SECURING YOUNG FARMERS

Promotion of establishing farm business

In Japan, a new policy framework called ‘farm business policy’, as a part of agricultural policy reform characterized by market orientation, has been established to promote farm expansion by farmland accumulation and stabilize farm income since 1992. Although there have been some amendments to this policy such as the start of direct payment in the 2000s, it remains largely unchanged today. Priority has been given to the measures aimed at the establishment of ‘efficient and stable farm businesses’. Further, as large numbers of farmers began to retire, it has been recognized as an opportunity to accelerate structural change rather than a cause of an anxiety about the shortage of the population of farmers.

The government has also paid attention to the ‘farmer’ side issue. In 1995 a loan program targeting young people entering agriculture started. This program still plays an important part in the ‘farmer’ related policies. The beginning farmer centers were set up in all of prefectures to manage the loan program. This center works as a window office to accept and advise people wishing to enter the agricultural sector. The Basic Law on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas was enacted in 1999 and the article 25 titled “secure and foster talented farmers” amongst other things was placed in it, and the support policies for beginning farmers have been reinforced legally.

However, the government has had much concern about the ‘farm’ side issue and recognized that the establishment of farm business through structural change were required as a basic condition to increase the number of new entrants into farming.

The government’s 1992 policy, promoting farm land accumulation and stabilizing farm incomes, highlights the apparent trend. The goal of 1992 policy was to establish farm business operating a certain number of acreage of farmland in about ten years. In case of a family farm growing rice, the model was cultivating 10-20 hectares, which enabled a farmer to work 1,800-2,000 hours per year and earn $2.0 million -$2.5 million within a lifetime. The hours and income were equivalent to the conditions of workers engaged in other industries.

Moreover, the direct payment policy, started in 2007, requested community based farms organized by many small farmers to establish “efficient and stable farm business” to receive income support from the government, and stipulated setting the goal of income of an operator mainly in farming, in addition to other conditions such as acreage of farmland of 20 hectares and more, unified accounting as a sole business organization, and setting a plan to incorporate. Although the working hour condition has been eliminated, the government still intends to increase the number of young farmers through establishing ‘farms’ that can realize a target income. Further, this policy is widely accepted by the rural population.

Is farm business policy effective on securing farmers?

It is appropriate to assume that the establishment of farm business realizes a target income and enables to increase the number of new entrants into farming. However, the goal of the policy of securing ‘farmers’ can be accomplished only by such a farm business policy to establish farm business?

Fig. 1 shows the proportion of farm families holding a farm successor. This shows that, as farmland acreage increases so does the percentage of farm families holding a farm successor. However, the difference is not large. 67% of farm families of 30 hectares or more have successors while 54% of farm families of less than one hectare have successors. The difference increases if successors are regarded as all those living with the farm owners and those only engaged in farming or mainly engaged in farming. When this limited farm successor definition is applied, just 4% of farms of less than one hectare have successors and 45% of farms of 30 hectares or more. Yet the rate of farm families with successors still does not reach 50% even in case of those operating large farmland. Evidence suggests farm establishment influences new entrants’ behavior into farming, yet it does not secure enough entrants.

To fully understand this issue, we need to examine the followings:

Despite the accumulation of farmland, incomes may not necessarily increase proportionally. This is because farm incomes are influenced by a variety of factors.

2. Do enough people want to enter farming?

Even if income targets are realized and not enough people want to become farmers, new entrants cannot be secured. This is supply side matter of new farmers.

Effect of income support for beginning farmers

Agricultural policies to support beginning farmers started in 1995 with no interest loan program. More than a decade later, in 2008, agricultural employment promotion started. In 2012, a subsidy program was established to assist a new generation of farmers entering agriculture by the payment of $15,000 per year in 7 years at the longest to a beginning farmer. Polices for new entrants were systematically improved and the level of policy support has been upgraded. Although the policy initiatives may be a little late coming, the separation of ‘farmer’ focused policy from farm business policy seems to be a positive development. Fig. 2 examines the above by using the supply curve of new entrants. When the new entrants supply curve is S0 and income level is I0, and the number of new entrants is set at A. If farm business establishment is realized and income level goes up to I1, the number of new entrants increases from A to B. Moreover, if the supply curve shifts to S1 from S0 by income support while income level is the same, the number of new entrants will be set at C. Furthermore, the number of new entrants increases to D when there is a simultaneous improvement in income level and support.

DIFFICULTY TO RE-JOINT ‘FARM’ AND ‘FARMER’

The previously discussed issue reveals the flow economy of farm business and indicates that the number of new entrants into farming is influenced by income levels. Another issue involving farm stock and its economic impact exists. Transferring farms to new entrants isn’t easy, particularly as the size and associated assets of the farm increases. Farm assets can be divided into tangible and intangible assets. The following section discusses the difficulties associated with the transfer of each asset class.

Following the 1990s, policies to encourage young generation to enter agriculture has been developed. Recently measures to provide income support to beginning farmers were established. In the economic flow of farms, farm expansion leads to an increase in new agricultural entrants, while in the stock economy of farms, asset transfer is problematic, particularly with farm expansion. Farm asset transfer is a common problem in developed countries[1]. Issues around the intergenerational transfer of farm assets are beginning to surface in Japan. This issue focuses attention on the next generation of farm ownership and explores the issue regarding how to re-joint the ‘farm’ and the ‘farmer’.

Japanese farm families are facing difficulties in farm asset transfers by traditional farm succession practices and more suitable methods for intergenerational transfer are required even in case of a farm family with a successor. For example, some large farms have transferred assets by using the same measures as business succession planning for small companies in other industries. Further, some livestock farms use a venture capital funded by the government and the group of agricultural cooperatives to transfer farm assets.

Moreover, changing relationships and family dynamics are beginning to cause increasingly difficult farm transfers. Traditionally family farms are characterized by an extended family, where two or three generations live together on the farm and there is a sole inheritor. A sole inheritance custom used be connected with maintaining farming and farm family including care for old parents. Increasingly many issues are emerging around farm succession. Examples include:

In particular, claims for divided succession are gaining strength, challenging the traditional custom of sole inheritance. Improved family communications and methods for amicable and fair family agreements are required to ensure smooth farm business succession.

Farm asset transfer in the case of non-related parties is more difficult than in the case of the transfer from parents to children. However, as Fig. 1 shows, only small portion of farm families has secured successors devoted to farming. This trend also includes farm families of 30 hectares and more. The transfer of farm assets to new entrants, that do not have a background in farm family, is becoming a significant issue for Japanese land-use agriculture.

NEW ENTRANCE INTO HOKKAIDO AGRICULTURE

Farm transfer as a part of major issues Hokkaido agriculture faces

Hokkaido agriculture is well known for the history of the agricultural development since the late 19th century and its different characteristics such as large shares of products of dairy farming and crop farming growing potato, wheat, beans and sugar beet like western countries, and relatively large and business oriented farms devoted into farming without any other job and business. It’s quite different from other prefectures in Japan where many farmers are part-time ones or elder generation operating rice farming with small paddy field.

Hokkaido agriculture is the most productive part in Japanese agriculture but it has faced such problem of farm asset transfer from early time. In 2005, only 24.6% of farm families in Hokkaido, while 55.4% in other prefectures, had successors, although in Hokkaido the percentage of farm successors only or mainly engaged in farming is much higher than other prefectures. Because not all family farms can be transferred successfully, the Hokkaido prefectural government, local governments, JA (Japanese Agricultural Cooperative) and the Hokkaido Agricultural Development Corporation have begun to support new farm entrants. In the past 10 years between 2006 and 2013, 5,162 people have entered agriculture, with 609 (11.8%) not being the family farm successor. The beginning farmers without a farm family background are an indispensable part of new entrants in Hokkaido agriculture. And total number of new entrants without farm family background during the same period is 17,480, and the proportion of such entrants into Hokkaido agriculture is 3.5%.

Table 2 shows the number of new entrants into Hokkaido agriculture and those without farm family background from the point of type of farming. According to this, new entrants without farm family background used to be the largest in dairy farming but the most popular type in past 5 years is vegetable.

As farm businesses in Hokkaido are comparatively large and many farmers wish to sell assets, such as farmland, when they quit or retire, new entrants are forced to find large sums of money to finance farm purchases. Moreover, the acquisition of intangible assets, including high level farm business management and production technology knowledge and skills, is necessary for beginning farmers. This reduces the risk of early financial failure and ensures the financial stability of the farm.

Various supports for beginning farmers

Table 3 shows the various measures taken to help solve the difficulties beginning farmers face, which include supports for acquiring tangible and intangible assets, and continue after the start of farming. They covers issues widely from farm business and tax to living conditions. Support program is arranged differently depending upon the type of farm business operation. This is influenced by which type of farm and a new entrant candidate a support organization chooses to accept and back[2].

A key difference amongst types of entry to agriculture is size of farm assets (Table 4). Greenhouse cultivation growing vegetables and flowers are examples of small farm assets. Fixed assets are comparatively small and the initial investment in this asset class can be low. Alternatively, land-use agriculture generally has large assets. This is particularly true for dairy farming, which typically includes a barn with a variety of facilities and vast forage fields.

However, asset costs can be reduced by contract farming and leasing farmland and machinery. Some new entrants to land-use agriculture have established small asset based farms by leasing land where farmland prices are high.

Another key difference to divide types of new entry is the standardization of farm businesses. Financial risks can be reduced by standardizing various aspects of farming. This includes providing production supplies, technology, sales of products, financing and business management. Further, risks to new entrants can be diminished by helping the beginning farmer reach and maintain these standard practices. The standardization of greenhouse cultivation is easier than other types of farming.

Some agricultural cooperatives in the dairy farming area have attempted to standardize dairy farm entry and thus hopefully reduce financial risks by establishing an educational farm for trainees to provide basic technology and skills to beginning farmers, and by setting up experiment farms for beginning farmers to manage actual dairy farming and spinning them out after making sure that their management become stable. The Hokkaido Agriculture Development Corporation (HADC) has offered a farm lease system to assist the transfer of farm assets. In many cases, local organizations have new entrants start farming by using HADC program after two to three years training on a farm or facility to them. Thus, the process from the acceptance of new entrants to the start of farming has been standardized.

On the other hand, many types of farming cannot be standardized. Diversified farms, growing several crops or livestock are difficult to be standardized. In diversified farming areas, it seems difficult to accept new entrants but recently some areas have started a support program in order to maintain the population of famers and agricultural resources.

As initial investment increases in size so does financial risk. Financial support for the acquisition of tangible assets is required to reduce such a risk. Due to the comparatively small initial investment required, and the accompanying smaller risks, greenhouse cultivation and lease type farming do not require large amounts of economic support.

Generally, a standardized farm with large assets, which is typically a dairy farm, requires local government or agricultural cooperative support. This type of farm is noted in Table 3, case B. Because of the large amount of support required for dairying, the number of new entrants who can receive support is necessarily small. In contrast, a farm that is not standardized and has small assets (case C in Table 4) requires little support. Therefore, it becomes possible to increase the number of new entrants. In such a case, there are many new entrants with various wishes for farming or living in country side, but their businesses are not always successful and the entrance and exit is repeated frequently as a result.

Moreover, the risk of failure can be reduced most effectively for standardized farms with small assets (case A). Greenhouse cultivation is a typical example of this type. On the other hand, farms that are not standardized and have large assets (Case D) face the largest risk of collapse. To reduce the financial risks associated with farm succession for non-related entrants, careful consideration of this transaction is needed. A strong and durable relationship over several years needs to be built between the farm owner and the successor so that both tangible and intangible assets are transferred. In the town of Bifuka, some dairy farm owners who did not have children who were able to be farm successors built an organization to promote farm succession to non-related entrants.[3]

A variety of schemes, in different areas of Hokkaido, attempt to solve the difficult problems faced in transferring farm assets to beginning farmers. Although the establishment of support mechanisms for beginning farmers requires time and effort, these initiatives help re-joint a ‘farm’ and a ‘farmer’ and establish farm ownership. This greatly not only assists new entrants to agriculture and but also benefits the revitalization of land use agriculture.

CONCLUSION

When the government started farm business policy in 1990s, how to restructure small farms was focused on in order to increase new entrants into agriculture. On the other hand, a new problem of farm transfer has been appeared and the nature of this problem is an excess of farm assets for new entrants.

It’s necessary to realize a certain level of farm size to get enough farm income, but it’s difficult to have farm assets, both tangible asset and intangible asset, in a short period for new entrants without farm family background.

To solve the problem of an excess of farm assets, farm assets should be divided into small pieces and transferred to several farmers or the process of farm transfer must be extended so that farm assets can be taken over gradually. We have to consider the system to realize such farm transfer and also how to get enough income from small piece of farm asset. Eventually, it’s important to establish a business model which is fit for new entrants and a method to reach it.

A dairy farming in Hokkaido is a typical farm business with large assets. Over $1 million is required as an initial investment for new entrance and a farm transfer has been becoming quite difficult.

Recently many new entrants are interested in intensive grazing with comparatively low investment and small number of cows, and they are thinking of the way of farm business to get income by raising up the income ratio to total sale. This is a good example of an action toward establishing a business model for new entrants.

REFERENCES

Hokkaido Agricultural Development Corporation (HADC) and Hokkaido Regional Agriculture Research Institute (HRARI). 2012. Securing farm business entities and the conditions of their settlement; cases of new entrants.

Sakai, J., S. Yanagimura, F. Ito and K. Saito. 1998. Succession and Entrance to Agriculture. Rural Culture Association, Tokyo, Japan.

Yanagimura, S., Y. Yamauchi and K. Higashiyama. 2012. Risk Reduction and Characteristics of Farm Transfer to Non-related Parties, Japanese Journal of Farm Management, 50(1): 16-26.

[1] Sakai et al. (1998) discussed the problem of intergenerational farm transfer in Japan compared with the USA and the European countries.

[2] HADC and HRARI (2012) shows many cases of new entrance into Hokkaido agriculture without farm family background.

[3] Yanagimura et al. (2012) analyzed the function of this organization.