Kampanat Pensupar1*, Itthipong Mahathanaseth2, Panan Nurancha 3

1 Center for Applied Economic Research, Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 10900; E-mail address:

fecoknp@ku.ac.th

2 Department of Agricultural Economics and Resources, Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 10900

3 Center for Applied Economic Research, Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 10900

ABTRACT

ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) was established under the crucial objective which encourages intra-trade between state members. A major evidence of this attempt is to formulate an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) by 2015. In principle, goods and services of its member countries need to be freely moved within the trade bloc. However, after tariff barriers were eliminated, several non-tariff measures are introduced and most of them are mainly applied to agricultural products. These practices are regarded as erroneous implementation of AEC state members. ASEAN countries should strengthen their cooperation through trade liberalization rather than blocking each other’s imports. This is an appropriate means to enhance their competitiveness in the world economy.

Keywords: ASEAN Free Trade, ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), Non tariff Barriers, Agricultural Trade

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural sector has historically played vital roles in the Thai economy. A large number of Thai populations still practice traditional agriculture, or live agrarian life. In 2011, it is approximated that 24.1 million Thais are farmers, accounting for 37.64% of its total population (Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2012a). Besides, agricultural sector is regarded as a major source of export earnings of Thailand. In 2011, Thailand obtained approximately US$48,233 million from agricultural exports, accounting 21.03% of her total export incomes (Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2012a). However, the prospect of Thailand’s agricultural exports is apparently being threatened by the world economic slowdown and international trade restrictions. Strategically, Thailand has participated in both intra- and inter-regional free trade agreements (FTAs) in order to create opportunities for trades and get rid of trade barriers. Up to this year, 12 free trade agreements signed by Thailand have been enforced, including mutual FTA among 6 ASEAN members and bilateral agreements with 6 countries outside ASEAN consisting of Australia, New Zealand, India (for only early harvested commodities), Japan, China and South Korea. Especially, ASEAN free trade agreement or AFTA, which has been implemented since 1992, is the first free trade agreement of Thailand.

Thailand is one of the 5 founding members of the ASEAN, which was established in 1967. Later, membership has expanded to include Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. It was not until 1992 when the ASEAN free trade area was formed. Since then, Thailand had to lift all quotas and impose zero-rate tariffs on agricultural imports from the members, except for some commodities categorized in the sensitive list (SL) of which the tariff rates were not necessarily equal to zero but no greater than 5%; for those commodities classified to be the highly sensitive list (SHL), their tariffs must have been reduced to the agreed rates.

Undoubtedly, the impacts of the ASEAN FTA on Thailand’s agricultural sector are both positive and negative. Among others, small farmers, agro-industries, exporters and importers are most likely to be affected. Therefore, a thorough analysis of current situation as well as an assessment of potential impacts is required, so that appropriate precautionary plans and measures will be acquired and implemented in order to help those who are most vulnerable to the harmful effects of free trade to adapt and survive in the long run.

ECONOMIC INTEGRATION FRAMEWORK

Free trade area

A free trade area is a kind of trade bloc based on the principle of comparative advantage. First formulated by David Ricardo, an influential neoclassical economist, in the early 19th century, the term “comparative advantage” refers to the ability of a country to produce a particular good or service at relatively lower costs than others. Natural resources, climate, geography, skill and size of labor forces, among others-all, these can contribute to make a country good at producing a certain thing (Krugman et al., 2010). The mutual benefits of international trade to countries or the so-called gains from trade occur, when each country decides to produce products in which it has a comparative advantage and then exchanges its products for its partners’ products in which it has comparative disadvantage. Hence, according to the theory of comparative advantage, tariffs, taxes, quotas, and other trade barriers are likely to twist comparative advantage among countries, impede efficient resource allocation, and therefore, deprive them of the gains from trade.

Motivated by the potential gains from trade, participating countries agree to establish a free trade area whose main objectives are to eliminate trade barriers and to promote free trade among each other. Within a bloc, all protections to domestic producers and preferential treatments with respect to specific members are unacceptable, except for safety controls over some commodities considered hazardous to population’s health and national securities. However, usually, members of a free trade area do not have common external tariffs meaning that they are allowed to have different quotas and customs as well as other trade regulations with non-member states.

ASEAN Free Trade AREA (AFTA)

ASEAN Free Trade Area or AFTA is a trade bloc agreement among the 10-member states of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) consisting of Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The primary goals of AFTA are to: 1) enhance ASEAN’s competitiveness as a production base in the world markets by eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers among the member states and promoting free trade; 2) attract more foreign direct investments to the region. In principle, the first goal - to get rid of tariffs imposed on products imported from the member states – is to be achieved by a consequence of bilateral agreements between a pair of countries to give preferential tariff rates to each other, that is, if two members decide to bestow preferential tariff rates on specific products to each other, they are automatically forced to reduce the tariff rates on these goods from other members as well.

The rule of origin also applied to qualify products for preferential tariff rates. The general rules are that local ASEAN content must be at least 40% of the FOB value of the goods and ASEAN raw materials must accumulatively account for at least 20% of total raw material costs.

In 1998, under the Hanoi Action plan, the states member declares the intention to step forward closely in the cooperation. Strengthening comparative advantage of this region through free movement of goods and services, investments, skilled labor and FDI was established. After that in 2003, under the Declaration of the ASEAN Concord II, an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was then established.

In principle, ASEAN members have agreed to enact zero tariff rates on almost all imports by 2010 and 2015 for the four CLVM countries consisting of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. Thus, in 2015, all tariffs barriers against the ASEAN members will be totally abolished.

INTERNATIONALT RADE MEASURES

International trade measures are generally categorized into two measures which are tariff and non-tariff measures. They can be further classified in details as follows.

Tariff measures

Tariffs are taxes commonly imposed on imported products. After being taxed, the prices of imported goods increase, so consumers are encouraged to purchase more domestic products. Strategically, not only are they regarded as reliable tools to protect domestic production from foreign competition, but they are also sources of government revenue.

Non-tariff measures

Non-tariff measures are direct governmental interventions on restricting consumers’ choices, oftentimes leading to inefficient resource allocation. Two or more non-tariff measures are usually coupled together or with tariff measures for more effectiveness. The non-tariff measures can be classified as follows:

Para-tariffs are extra taxes, imposed on imported goods in addition to the normal tariffs, usually based on volume or quantities; for example, customs surcharge, additional charges, internal taxes and charges levied on imports and decreed customs valuation. All of these measures are intended to increase costs of imported goods as the tariffs.

Price control measures are often exploited to restrict imports, stabilize domestic commodity prices, and especially prevent dumping of cheaper foreign goods.

Finance measures are financial legislations to impede imports of goods, for instance, collateral requirements and advance taxes and tariffs. These measures, similar with other non-tariff barriers, are ultimately done to increase costs of imported goods.

Automatic licensing measures are procedures and rules not relating with import prohibitions. But it can be applied together with anti-dumping together with the environmental measures.

Quantity control measures are to impose limit on quantities of imported goods either from all or some specific countries. Quotas and import licensing are the typical examples of quantity control measures.

Monopolistic measures allow only government or some specific importers to import goods from all or some countries.

Technical measures are to specify prohibited characteristics of imported goods such as size, quality, labels, and packaging. Some technical requirements such as sanitary conditions and testing procedures are also included.

In terms of overall trade in the ASEAN, Plummer et al. (2009) indicated that in 2006, intra-trade between member states increased approximately 26%. Small growth rate of intra-trade in the ASEAN is because these member states are SMEs. Therefore, most of their trade partners belong to the rest of ASEAN countries. While intra-trade in the ASEAN, non tariff measures are considered to be the most crucial barrier.

AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS AND THEIR EFFECTS UNDER AFTA

Thailand joined AFTA on January 1, 1992 and had to eliminate quotas and reduce tariffs to zero, except for those in the sensitive list (SL) such as coffee beans, potato flowers and dried coconut copra. These do not have to be reduced to 0% but must be brought down to the 0-5% tariff range.

Moreover, Thailand had to lift or remove its Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) including the following groups of products, which are largely Tariff Rate Quota (TRO)

First NTBs: From January 1, 2008, five products were covered: longan, pepper, tobacco, soybean oil and sugar.

Second NTBs: From January 1, 2009, three products were covered: ramie, jute plant and potato.

Third NTBs: The Ministry of Commerce announced that 10 products would be exempted from the list of TRQ which included: coconut oil, tea, coffee bean, instant coffee, fresh milk, flavored milk and skimmed Milk but rice was not yet included.

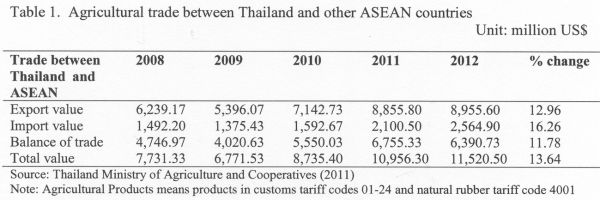

It has been found that the import export value of agricultural products between Thailand and the ASEAN after the instigation of AFTA since January 1, 2011 has tended to increase as shown in Table 1. The total trade value between Thailand and the other nine ASEAN countries was US$7,000 million but after the reduction of tariffs between ASEAN countries in 2011, the trade value increased to US$8,735 million and to US$11,520 million in 2012.

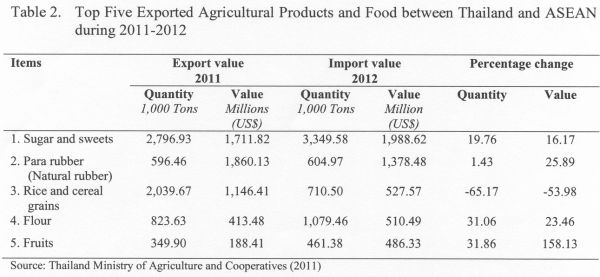

If all products are categorized, it can be found that among the important agricultural products and food for export in 2012, sugar and other sweets held the highest rank with the value of US$1,711.82 million in 2011 and increased to US$1,988.62 million in 2012 or a 16.17% increase. The second most exported group of products included natural rubber, rice and cereals, flour products and fruits as shown in Table 2.

Though the total value of agricultural products has increased, possibly resulting from free trade policy, it was found that other ASEAN countries still had other restrictions to protect their own agriculture, most of which are non-tariff barriers. Such restrictions might jeopardize genuine free trade between countries and limit the objectives of the AFTA.

Currently, ASEAN member countries have issued various import regulations including safeguard measures and other rules. For example, Indonesia launched at least 100 new safeguard measures to control the import of vegetables, fruits, and tuber crops including red onion. These vegetables and fruits have to be free of chemicals and other biological hazards, such as pests or other insects. The measures include the prohibition of chemically-tainted foods that could jeopardize consumers’ health. Furthermore, Indonesia has a specific restriction on Hom Mali rice. It has to be declared as a supplementary diet for good health. The importer has to be registered with and ask permission from the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture and each product delivery has to be authorized by the Indonesian Ministry of Commerce. Red onions also suffer from import restrictions. It has to be both root-cut and head-cut before they are imported. This costs extra money for Thai exporters and it significantly accelerates the product’s decay. Those restrictions aim to control and block the import of agricultural products, especially fruits and vegetables, leading to problems and obstacles related to the products exported from Thailand to Indonesia, which is a large, important market for Thai agricultural products.

Moreover, there have also been similar cases with Malaysia and the Philippines. The Philippines issued a regulation for the import of fresh and frozen chicken, fresh and frozen beef, and fresh and frozen pork. The factories have to be officially inspected and certified by the Philippine authorities. Even though Thailand was finally exempted from this restriction on 14 August 2012, the Philippine authority, however, has not issued permission letters for Thai exporters. Similarly, Malaysia has given full authorization to Padiberas Nasional Berhad (Bernas) as the sole importer of rice. Now and then there have been non-negotiable issues between countries, such as the agreed price of rice. The Thai fisheries industry has also suffered from the safeguard measures. The Fisheries Development Authority of Malaysia (LKIM) has strictly required that plastic fish storage containers must be products of Malaysia only. This means additional costs for Thai exporters. Moreover, the transportation restriction is another problem. Thai investors are prohibited to use their own delivery trucks to cross the border between Thailand and Malaysia. Delivery trucks must be from Malaysia. The products must be transferred at the border and the delay might cause severe damage to agricultural products. Furthermore, Malaysia strictly requires that all transportation moving in and out of Malaysia must be registered and insured in Malaysia. These safeguard measures have become major obstacles and problems for Thai business sector and investors who are forced to incur higher expenses.

TENDENCY FOR AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS IN THE FUTURE

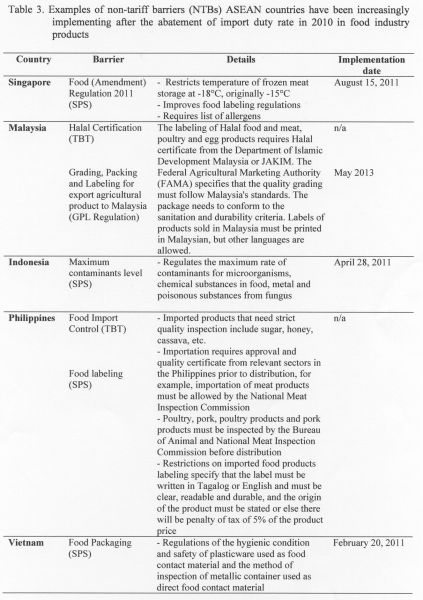

In the future, even though the export value of agricultural products is likely to increase, every ASEAN country trends to issue safeguard measures and restrictions that are not tariffs. The effects of FTAs leading to agreement on eliminating or reducing tariffs cause the widespread adoption of non-tariff Barrier policies instead of tariffs to protect domestic investors and the business sector. Moreover, the critical condition of the world economy forces every country to adopt safeguard measures. After joining AFTA, each country adds more non-tariff barriers which largely include Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures: (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT). They often use the safety of life and the health of the people in their country as reasons to implement NTBs. These policies do not violate the agreement of AEC. Some measures have direct effects on the manufacturing process and the manufacturers because they need to develop higher standards of manufacturing process in order to be able to match the advancement of technology in inspecting the products from other countries, especially in the food industry, which is one of the most important export business sectors. These export business sectors will suffer more from NTBs. Several NTBs have been effective after the reduction of tariff rate to 0% since 2010 (See Table 3). Instead of gaining benefit from AFTA, Thailand has suffered from the safeguard measures causing limitations to trade between ASEAN countries.

THE POTENTIAL OF, AND THE OPPORTUNITIES FOR, THAI AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS UNDER THE ASEAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT

Overall, Thai agricultural products are competitive in both the ASEAN and world markets. The study of competitiveness of Thai agricultural products in the ASEAN and the global market by the Center for Applied Economics Research (2011) shows that important types of competitive Thai agricultural products include rice, para rubber and Vannamei shrimp. Considering the proportion of rice production of countries in the ASEAN region from 2002-2009, the country that produced the largest amount of rice product in the ASEAN was Indonesia, with the proportion of approximately 32% of the entire ASEAN countries' rice production. The countries with the second highest rice production rate were Vietnam and Thailand. The Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) study in 2009 revealed that Vietnam was the most competitive country, with an RCA value of 54.23, while Thailand's RCA value was 5.37. In terms of quality, Thailand's rice product was considered high-quality and had high-standard production, which resulted in a higher export price than Vietnam, Thailand's important competitor, who has won a share of Thailand's important rice market in the Philippines and Singapore.

With regard to Thailand's shrimp production, the country had the highest production rate among the area of ASEAN as a result of Thailand's advanced shrimp farming technology, as well as the country's basic geographical structure that benefits shrimp farming. However, the calculation of Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index of shrimp production in the ASEAN countries discovered that in 2009, Vietnam was the most competitive country compared to other ASEAN countries, with an RCA rate of 7.03. The second most competitive was Thailand, with an RCA value of 3.15. Nevertheless, Thailand is starting to have problems with the increasing cost of shrimp food and the deterioration of natural resources.

However, the analysis of competitiveness using the Boston Consulting Group Matrix (BCG) model of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (2012b) specified groups of product with which Thailand was in "Trouble" condition in the ASEAN market. These products were coconut, coffee beans and palm oil. For rice, para rubber and shrimps, the analysis results showed that Thailand's rice and shrimp products in the ASEAN market fell into "Question Mark" status, while para rubber was in "Falling Star". In terms of all products, Thailand is more competitive than other ASEAN countries, but Thailand has a low growth rate of exports because it is a big exporter of such products. As a result, Thailand's export growth rate of such products is lower than other competitors. However, Thailand can benefit from the establishment of the ASEAN economic community by exporting important agricultural products as well as relocating the country's agricultural product manufacturing bases to other ASEAN countries.

CONCLUSION

The effects of establishing a free trade zone are evident. In Thailand, for example, the establishment of free fruits and vegetables importation with China under the arrangement of Chinese-ASEAN made it impossible for Thai garlic farmers to compete against garlic producers in China. Another example is when Indonesia imported onions from Thailand and Vietnam, which affected a large number of Indonesian farmers and laborers. Such situations make ASEAN members to seek paths to adapt and enhance the competitiveness of their own agricultural products, as well as to think of ways to prevent products from other ASEAN members to easily enter their countries. For example, Thailand has regulated the time duration for importing corn, the ingredient used in animal food production, which is allowed to be imported, according to the ASEAN free trade agreement, only from March 1 to August 31 (Announcement of the Ministry of Commerce, July 2013). Importation outside this time frame does not come under the rights of the ASEAN free trade arrangement. While other ASEAN countries have implemented non-tariff trade barriers, especially Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), which trend to be significantly more intense, what both entrepreneurs and the government should urgently focus on is the promotion of farmers to improve the agricultural practices and production in vegetation, livestock and fisheries. Meanwhile, the government should place importance on negotiations to establish common standards for agricultural products among ASEAN members, which will provide guidance for agriculturists in ASEAN countries to acknowledge and adapt agricultural product manufacturing. At the same time, ASEAN members should pay attention to the implementation of ASEAN manufacturing standards in order to prevent low quality agricultural goods, (which do not meet the standard and are cheaper), from competing against high quality agricultural products. Furthermore, agencies responsible for quality-checking should work together to propose a policy to implement equivalent monitoring technology and reduce the steps of the checking process to make it more convenient for tariffs in ASEAN countries and to set a single ASEAN window.

The Government should encourage agriculturalists to be omniscient and professional in production i.e. be able to analyze and make decisions during the manufacturing process consistent with management and marketing principles, to pay attention to green technology, the reduction of waste release, the proper use of water, the reduction of environmentally unfriendly agriculture (World Economic Forum, 2011; Zamroni, 2006), and to promote the agricultural industry as sources of demand for agricultural products within the country, leading to value-added creation of local agricultural products, as well as to develop the infrastructures that benefit agriculture such as irrigation and transportation systems. Thailand should focus on producing goods that are suitable for its geographical location. The Thai government is currently running the Smart Farmer project to comply with this idea. In addition, the government should eliminate some policies and measures that distort the market mechanism. The government can continue applying some policies that provide advantages to the agriculturalists to adapt and to be able to improve themselves when dealing with the ASEAN free trade in the future, and to help disadvantaged farmers to cope with their lives as agriculturalists. The method which the government should focus on is to conduct research and development for the agricultural sector to improve agricultural productivity.

However, such a process should be carried out simultaneously in all ASEAN countries to keep ASEAN's actions relevant to the main objective, that is, to enhance their competitiveness in the world economy and thereby obtain mutual benefits from trades, instead of building up themselves in order to compete against each other within the ASEAN countries.

REFFERENCES

Krugman, P., M. Obstfeld and M. Melitz. 2010. International Economics: Theory & Policy. 9th edition. Pearson, New York, USA.

Plummer, M., and C.S. Yue. 2009. Realizing the ASEAN Economic Community: Comprehensive Assessment. Utopia Press, Singapore.

Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. 2012a. Report on Current Situations of Thai Agricultural Products under AFTA and FTA (enacted only) in December 2011. Bangkok: Office of Agricultural Economics. (In Thai)

_____________. 2012b. An Analysis on Competitiveness of Thailand’s Important Agricultural Products: TCM Approach. Bangkok: Office of Agricultural Economics. (In Thai)

_____________. 2011. Thailand’s Agricultural Trade Statistics. Bangkok: Office of Agricultural Economics. (In Thai)

The Center for Applied Economic Research. 2011. The Study Project on R&D Mechanism in Agricultural and Food Industry of Thailand for ASEAN Economic Integration Preparation in 2015. Bangkok: the Thailand Research Fund. (In Thai)

The Center for International Trade Studies, University of Thai Chamber of Commerce. 2008. An Analysis on the Impacts of ASEAN Community (AEC) on the Thai Economy in the Next 6 years. Bangkok: University of Thai Chamber of Commerce. (In Thai)

World Economic Forum, 2011. Realizing a new vision for agriculture: A roadmap for stakeholders (online). www3.weforum.org/docs/wef_ip_nva_roadmap_report.pdf. August, 13 2012.

Zamroi, S. 2006. “Thailand’s Agricultural Sector and Free Trade Agreements.” Asia-Pacific Trade and Investment Review. 2, 2: 51-70.

|

Submitted as a resource paper for the FFTC.NACF International Seminar on Threats and Opportunities of the Free Trade Agreements in the Asian Region, Sept. 29-Oct. 3, 2013, Seoul, Korea |

The Current Status and Future Perspective sof Agricultural Trade in Thailand under ASEAN Free Trade

ABTRACT

ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) was established under the crucial objective which encourages intra-trade between state members. A major evidence of this attempt is to formulate an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) by 2015. In principle, goods and services of its member countries need to be freely moved within the trade bloc. However, after tariff barriers were eliminated, several non-tariff measures are introduced and most of them are mainly applied to agricultural products. These practices are regarded as erroneous implementation of AEC state members. ASEAN countries should strengthen their cooperation through trade liberalization rather than blocking each other’s imports. This is an appropriate means to enhance their competitiveness in the world economy.

Keywords: ASEAN Free Trade, ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), Non tariff Barriers, Agricultural Trade

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural sector has historically played vital roles in the Thai economy. A large number of Thai populations still practice traditional agriculture, or live agrarian life. In 2011, it is approximated that 24.1 million Thais are farmers, accounting for 37.64% of its total population (Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2012a). Besides, agricultural sector is regarded as a major source of export earnings of Thailand. In 2011, Thailand obtained approximately US$48,233 million from agricultural exports, accounting 21.03% of her total export incomes (Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2012a). However, the prospect of Thailand’s agricultural exports is apparently being threatened by the world economic slowdown and international trade restrictions. Strategically, Thailand has participated in both intra- and inter-regional free trade agreements (FTAs) in order to create opportunities for trades and get rid of trade barriers. Up to this year, 12 free trade agreements signed by Thailand have been enforced, including mutual FTA among 6 ASEAN members and bilateral agreements with 6 countries outside ASEAN consisting of Australia, New Zealand, India (for only early harvested commodities), Japan, China and South Korea. Especially, ASEAN free trade agreement or AFTA, which has been implemented since 1992, is the first free trade agreement of Thailand.

Thailand is one of the 5 founding members of the ASEAN, which was established in 1967. Later, membership has expanded to include Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. It was not until 1992 when the ASEAN free trade area was formed. Since then, Thailand had to lift all quotas and impose zero-rate tariffs on agricultural imports from the members, except for some commodities categorized in the sensitive list (SL) of which the tariff rates were not necessarily equal to zero but no greater than 5%; for those commodities classified to be the highly sensitive list (SHL), their tariffs must have been reduced to the agreed rates.

Undoubtedly, the impacts of the ASEAN FTA on Thailand’s agricultural sector are both positive and negative. Among others, small farmers, agro-industries, exporters and importers are most likely to be affected. Therefore, a thorough analysis of current situation as well as an assessment of potential impacts is required, so that appropriate precautionary plans and measures will be acquired and implemented in order to help those who are most vulnerable to the harmful effects of free trade to adapt and survive in the long run.

ECONOMIC INTEGRATION FRAMEWORK

Free trade area

A free trade area is a kind of trade bloc based on the principle of comparative advantage. First formulated by David Ricardo, an influential neoclassical economist, in the early 19th century, the term “comparative advantage” refers to the ability of a country to produce a particular good or service at relatively lower costs than others. Natural resources, climate, geography, skill and size of labor forces, among others-all, these can contribute to make a country good at producing a certain thing (Krugman et al., 2010). The mutual benefits of international trade to countries or the so-called gains from trade occur, when each country decides to produce products in which it has a comparative advantage and then exchanges its products for its partners’ products in which it has comparative disadvantage. Hence, according to the theory of comparative advantage, tariffs, taxes, quotas, and other trade barriers are likely to twist comparative advantage among countries, impede efficient resource allocation, and therefore, deprive them of the gains from trade.

Motivated by the potential gains from trade, participating countries agree to establish a free trade area whose main objectives are to eliminate trade barriers and to promote free trade among each other. Within a bloc, all protections to domestic producers and preferential treatments with respect to specific members are unacceptable, except for safety controls over some commodities considered hazardous to population’s health and national securities. However, usually, members of a free trade area do not have common external tariffs meaning that they are allowed to have different quotas and customs as well as other trade regulations with non-member states.

ASEAN Free Trade AREA (AFTA)

ASEAN Free Trade Area or AFTA is a trade bloc agreement among the 10-member states of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) consisting of Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The primary goals of AFTA are to: 1) enhance ASEAN’s competitiveness as a production base in the world markets by eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers among the member states and promoting free trade; 2) attract more foreign direct investments to the region. In principle, the first goal - to get rid of tariffs imposed on products imported from the member states – is to be achieved by a consequence of bilateral agreements between a pair of countries to give preferential tariff rates to each other, that is, if two members decide to bestow preferential tariff rates on specific products to each other, they are automatically forced to reduce the tariff rates on these goods from other members as well.

The rule of origin also applied to qualify products for preferential tariff rates. The general rules are that local ASEAN content must be at least 40% of the FOB value of the goods and ASEAN raw materials must accumulatively account for at least 20% of total raw material costs.

In 1998, under the Hanoi Action plan, the states member declares the intention to step forward closely in the cooperation. Strengthening comparative advantage of this region through free movement of goods and services, investments, skilled labor and FDI was established. After that in 2003, under the Declaration of the ASEAN Concord II, an ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was then established.

In principle, ASEAN members have agreed to enact zero tariff rates on almost all imports by 2010 and 2015 for the four CLVM countries consisting of Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. Thus, in 2015, all tariffs barriers against the ASEAN members will be totally abolished.

INTERNATIONALT RADE MEASURES

International trade measures are generally categorized into two measures which are tariff and non-tariff measures. They can be further classified in details as follows.

Tariff measures

Tariffs are taxes commonly imposed on imported products. After being taxed, the prices of imported goods increase, so consumers are encouraged to purchase more domestic products. Strategically, not only are they regarded as reliable tools to protect domestic production from foreign competition, but they are also sources of government revenue.

Non-tariff measures

Non-tariff measures are direct governmental interventions on restricting consumers’ choices, oftentimes leading to inefficient resource allocation. Two or more non-tariff measures are usually coupled together or with tariff measures for more effectiveness. The non-tariff measures can be classified as follows:

Para-tariffs are extra taxes, imposed on imported goods in addition to the normal tariffs, usually based on volume or quantities; for example, customs surcharge, additional charges, internal taxes and charges levied on imports and decreed customs valuation. All of these measures are intended to increase costs of imported goods as the tariffs.

Price control measures are often exploited to restrict imports, stabilize domestic commodity prices, and especially prevent dumping of cheaper foreign goods.

Finance measures are financial legislations to impede imports of goods, for instance, collateral requirements and advance taxes and tariffs. These measures, similar with other non-tariff barriers, are ultimately done to increase costs of imported goods.

Automatic licensing measures are procedures and rules not relating with import prohibitions. But it can be applied together with anti-dumping together with the environmental measures.

Quantity control measures are to impose limit on quantities of imported goods either from all or some specific countries. Quotas and import licensing are the typical examples of quantity control measures.

Monopolistic measures allow only government or some specific importers to import goods from all or some countries.

Technical measures are to specify prohibited characteristics of imported goods such as size, quality, labels, and packaging. Some technical requirements such as sanitary conditions and testing procedures are also included.

In terms of overall trade in the ASEAN, Plummer et al. (2009) indicated that in 2006, intra-trade between member states increased approximately 26%. Small growth rate of intra-trade in the ASEAN is because these member states are SMEs. Therefore, most of their trade partners belong to the rest of ASEAN countries. While intra-trade in the ASEAN, non tariff measures are considered to be the most crucial barrier.

AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS AND THEIR EFFECTS UNDER AFTA

Thailand joined AFTA on January 1, 1992 and had to eliminate quotas and reduce tariffs to zero, except for those in the sensitive list (SL) such as coffee beans, potato flowers and dried coconut copra. These do not have to be reduced to 0% but must be brought down to the 0-5% tariff range.

Moreover, Thailand had to lift or remove its Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) including the following groups of products, which are largely Tariff Rate Quota (TRO)

First NTBs: From January 1, 2008, five products were covered: longan, pepper, tobacco, soybean oil and sugar.

Second NTBs: From January 1, 2009, three products were covered: ramie, jute plant and potato.

Third NTBs: The Ministry of Commerce announced that 10 products would be exempted from the list of TRQ which included: coconut oil, tea, coffee bean, instant coffee, fresh milk, flavored milk and skimmed Milk but rice was not yet included.

It has been found that the import export value of agricultural products between Thailand and the ASEAN after the instigation of AFTA since January 1, 2011 has tended to increase as shown in Table 1. The total trade value between Thailand and the other nine ASEAN countries was US$7,000 million but after the reduction of tariffs between ASEAN countries in 2011, the trade value increased to US$8,735 million and to US$11,520 million in 2012.

If all products are categorized, it can be found that among the important agricultural products and food for export in 2012, sugar and other sweets held the highest rank with the value of US$1,711.82 million in 2011 and increased to US$1,988.62 million in 2012 or a 16.17% increase. The second most exported group of products included natural rubber, rice and cereals, flour products and fruits as shown in Table 2.

Though the total value of agricultural products has increased, possibly resulting from free trade policy, it was found that other ASEAN countries still had other restrictions to protect their own agriculture, most of which are non-tariff barriers. Such restrictions might jeopardize genuine free trade between countries and limit the objectives of the AFTA.

Currently, ASEAN member countries have issued various import regulations including safeguard measures and other rules. For example, Indonesia launched at least 100 new safeguard measures to control the import of vegetables, fruits, and tuber crops including red onion. These vegetables and fruits have to be free of chemicals and other biological hazards, such as pests or other insects. The measures include the prohibition of chemically-tainted foods that could jeopardize consumers’ health. Furthermore, Indonesia has a specific restriction on Hom Mali rice. It has to be declared as a supplementary diet for good health. The importer has to be registered with and ask permission from the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture and each product delivery has to be authorized by the Indonesian Ministry of Commerce. Red onions also suffer from import restrictions. It has to be both root-cut and head-cut before they are imported. This costs extra money for Thai exporters and it significantly accelerates the product’s decay. Those restrictions aim to control and block the import of agricultural products, especially fruits and vegetables, leading to problems and obstacles related to the products exported from Thailand to Indonesia, which is a large, important market for Thai agricultural products.

Moreover, there have also been similar cases with Malaysia and the Philippines. The Philippines issued a regulation for the import of fresh and frozen chicken, fresh and frozen beef, and fresh and frozen pork. The factories have to be officially inspected and certified by the Philippine authorities. Even though Thailand was finally exempted from this restriction on 14 August 2012, the Philippine authority, however, has not issued permission letters for Thai exporters. Similarly, Malaysia has given full authorization to Padiberas Nasional Berhad (Bernas) as the sole importer of rice. Now and then there have been non-negotiable issues between countries, such as the agreed price of rice. The Thai fisheries industry has also suffered from the safeguard measures. The Fisheries Development Authority of Malaysia (LKIM) has strictly required that plastic fish storage containers must be products of Malaysia only. This means additional costs for Thai exporters. Moreover, the transportation restriction is another problem. Thai investors are prohibited to use their own delivery trucks to cross the border between Thailand and Malaysia. Delivery trucks must be from Malaysia. The products must be transferred at the border and the delay might cause severe damage to agricultural products. Furthermore, Malaysia strictly requires that all transportation moving in and out of Malaysia must be registered and insured in Malaysia. These safeguard measures have become major obstacles and problems for Thai business sector and investors who are forced to incur higher expenses.

TENDENCY FOR AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS IN THE FUTURE

In the future, even though the export value of agricultural products is likely to increase, every ASEAN country trends to issue safeguard measures and restrictions that are not tariffs. The effects of FTAs leading to agreement on eliminating or reducing tariffs cause the widespread adoption of non-tariff Barrier policies instead of tariffs to protect domestic investors and the business sector. Moreover, the critical condition of the world economy forces every country to adopt safeguard measures. After joining AFTA, each country adds more non-tariff barriers which largely include Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures: (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT). They often use the safety of life and the health of the people in their country as reasons to implement NTBs. These policies do not violate the agreement of AEC. Some measures have direct effects on the manufacturing process and the manufacturers because they need to develop higher standards of manufacturing process in order to be able to match the advancement of technology in inspecting the products from other countries, especially in the food industry, which is one of the most important export business sectors. These export business sectors will suffer more from NTBs. Several NTBs have been effective after the reduction of tariff rate to 0% since 2010 (See Table 3). Instead of gaining benefit from AFTA, Thailand has suffered from the safeguard measures causing limitations to trade between ASEAN countries.

THE POTENTIAL OF, AND THE OPPORTUNITIES FOR, THAI AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS UNDER THE ASEAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT

Overall, Thai agricultural products are competitive in both the ASEAN and world markets. The study of competitiveness of Thai agricultural products in the ASEAN and the global market by the Center for Applied Economics Research (2011) shows that important types of competitive Thai agricultural products include rice, para rubber and Vannamei shrimp. Considering the proportion of rice production of countries in the ASEAN region from 2002-2009, the country that produced the largest amount of rice product in the ASEAN was Indonesia, with the proportion of approximately 32% of the entire ASEAN countries' rice production. The countries with the second highest rice production rate were Vietnam and Thailand. The Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) study in 2009 revealed that Vietnam was the most competitive country, with an RCA value of 54.23, while Thailand's RCA value was 5.37. In terms of quality, Thailand's rice product was considered high-quality and had high-standard production, which resulted in a higher export price than Vietnam, Thailand's important competitor, who has won a share of Thailand's important rice market in the Philippines and Singapore.

With regard to Thailand's shrimp production, the country had the highest production rate among the area of ASEAN as a result of Thailand's advanced shrimp farming technology, as well as the country's basic geographical structure that benefits shrimp farming. However, the calculation of Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index of shrimp production in the ASEAN countries discovered that in 2009, Vietnam was the most competitive country compared to other ASEAN countries, with an RCA rate of 7.03. The second most competitive was Thailand, with an RCA value of 3.15. Nevertheless, Thailand is starting to have problems with the increasing cost of shrimp food and the deterioration of natural resources.

However, the analysis of competitiveness using the Boston Consulting Group Matrix (BCG) model of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (2012b) specified groups of product with which Thailand was in "Trouble" condition in the ASEAN market. These products were coconut, coffee beans and palm oil. For rice, para rubber and shrimps, the analysis results showed that Thailand's rice and shrimp products in the ASEAN market fell into "Question Mark" status, while para rubber was in "Falling Star". In terms of all products, Thailand is more competitive than other ASEAN countries, but Thailand has a low growth rate of exports because it is a big exporter of such products. As a result, Thailand's export growth rate of such products is lower than other competitors. However, Thailand can benefit from the establishment of the ASEAN economic community by exporting important agricultural products as well as relocating the country's agricultural product manufacturing bases to other ASEAN countries.

CONCLUSION

The effects of establishing a free trade zone are evident. In Thailand, for example, the establishment of free fruits and vegetables importation with China under the arrangement of Chinese-ASEAN made it impossible for Thai garlic farmers to compete against garlic producers in China. Another example is when Indonesia imported onions from Thailand and Vietnam, which affected a large number of Indonesian farmers and laborers. Such situations make ASEAN members to seek paths to adapt and enhance the competitiveness of their own agricultural products, as well as to think of ways to prevent products from other ASEAN members to easily enter their countries. For example, Thailand has regulated the time duration for importing corn, the ingredient used in animal food production, which is allowed to be imported, according to the ASEAN free trade agreement, only from March 1 to August 31 (Announcement of the Ministry of Commerce, July 2013). Importation outside this time frame does not come under the rights of the ASEAN free trade arrangement. While other ASEAN countries have implemented non-tariff trade barriers, especially Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), which trend to be significantly more intense, what both entrepreneurs and the government should urgently focus on is the promotion of farmers to improve the agricultural practices and production in vegetation, livestock and fisheries. Meanwhile, the government should place importance on negotiations to establish common standards for agricultural products among ASEAN members, which will provide guidance for agriculturists in ASEAN countries to acknowledge and adapt agricultural product manufacturing. At the same time, ASEAN members should pay attention to the implementation of ASEAN manufacturing standards in order to prevent low quality agricultural goods, (which do not meet the standard and are cheaper), from competing against high quality agricultural products. Furthermore, agencies responsible for quality-checking should work together to propose a policy to implement equivalent monitoring technology and reduce the steps of the checking process to make it more convenient for tariffs in ASEAN countries and to set a single ASEAN window.

The Government should encourage agriculturalists to be omniscient and professional in production i.e. be able to analyze and make decisions during the manufacturing process consistent with management and marketing principles, to pay attention to green technology, the reduction of waste release, the proper use of water, the reduction of environmentally unfriendly agriculture (World Economic Forum, 2011; Zamroni, 2006), and to promote the agricultural industry as sources of demand for agricultural products within the country, leading to value-added creation of local agricultural products, as well as to develop the infrastructures that benefit agriculture such as irrigation and transportation systems. Thailand should focus on producing goods that are suitable for its geographical location. The Thai government is currently running the Smart Farmer project to comply with this idea. In addition, the government should eliminate some policies and measures that distort the market mechanism. The government can continue applying some policies that provide advantages to the agriculturalists to adapt and to be able to improve themselves when dealing with the ASEAN free trade in the future, and to help disadvantaged farmers to cope with their lives as agriculturalists. The method which the government should focus on is to conduct research and development for the agricultural sector to improve agricultural productivity.

However, such a process should be carried out simultaneously in all ASEAN countries to keep ASEAN's actions relevant to the main objective, that is, to enhance their competitiveness in the world economy and thereby obtain mutual benefits from trades, instead of building up themselves in order to compete against each other within the ASEAN countries.

REFFERENCES

Krugman, P., M. Obstfeld and M. Melitz. 2010. International Economics: Theory & Policy. 9th edition. Pearson, New York, USA.

Plummer, M., and C.S. Yue. 2009. Realizing the ASEAN Economic Community: Comprehensive Assessment. Utopia Press, Singapore.

Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. 2012a. Report on Current Situations of Thai Agricultural Products under AFTA and FTA (enacted only) in December 2011. Bangkok: Office of Agricultural Economics. (In Thai)

_____________. 2012b. An Analysis on Competitiveness of Thailand’s Important Agricultural Products: TCM Approach. Bangkok: Office of Agricultural Economics. (In Thai)

_____________. 2011. Thailand’s Agricultural Trade Statistics. Bangkok: Office of Agricultural Economics. (In Thai)

The Center for Applied Economic Research. 2011. The Study Project on R&D Mechanism in Agricultural and Food Industry of Thailand for ASEAN Economic Integration Preparation in 2015. Bangkok: the Thailand Research Fund. (In Thai)

The Center for International Trade Studies, University of Thai Chamber of Commerce. 2008. An Analysis on the Impacts of ASEAN Community (AEC) on the Thai Economy in the Next 6 years. Bangkok: University of Thai Chamber of Commerce. (In Thai)

World Economic Forum, 2011. Realizing a new vision for agriculture: A roadmap for stakeholders (online). www3.weforum.org/docs/wef_ip_nva_roadmap_report.pdf. August, 13 2012.

Zamroi, S. 2006. “Thailand’s Agricultural Sector and Free Trade Agreements.” Asia-Pacific Trade and Investment Review. 2, 2: 51-70.