Onanong Tapanapunnitikull and Siriluk Prasunpangsri2

lFaculty of Natural Resources and Agro Industry, Kasetsart University,

Chalermphrakiat Sakon Nakhon Province Campus, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand

2Faculty of Liberal Arts and Management Science, Kasetsart University,

Chalermphrakiat Sakon Nakhon Province Campus, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand

e-mail: csnslp@ku.ac.th

ABSTARCT

In the face of population growth, world’s per capita food consumption is also growing, requiring 60 per cent more food must be produced by 2050. Thailand could be referred as the Kitchen of the world, since Thailand is one of the world leaders in food exporter; the major commodities are cassava, sugar, fishery and rice. However, the labor force in agriculture sector has decreased gradually. In addition to unveil the reason for this decline, this paper examines the development of young farmers by institutional agents in Thailand the study illustrates the current situation and challenges of agriculture sector in Thailand. The empirical evidence suggests two attempts made by the different levels of collaboration. Firstly, efforts were taken amongst the public, private sectors and universities to encourage the young people reentry or reengage in agriculture sector. Secondly, national plan has put forward a strategy to stimulate/foster a new intake in agriculture sector. In addition, the study suggests ways to transform the national plan both at local and national level by considering short and long term tactics. Further suggestion is made to foster institutional level’s collaboration in enabling the implementation of the national strategy. Thus, this paper argues the condition for a paradigm shift in agriculture growth lies in cooperation strategically among all parties to achieve at local, national and regional level in the context of Thailand

Keywords: young farmers, agricultural development, cooperation, strategic management, agricultural entrepreneur

INTRODUCTION

Agriculture has long been important to Thailand development and has been viewed as “backbone” of Thailand. Over the past five decades, agricultural sector used to be the key engine of economic growth in Thailand. In 1960, the agricultural share in GDP was higher than industrial sector 32.1 per cent and 22.1 per cent respectively (Suwannarat, 2014). In 1961, the value of agriculture sector was about USD 781 million while the national GDP was USD 2,562 million (Ministry of Agriculture, 2011a). Nevertheless, the agricultural share in GDP has decreased dramatically to 8.3 percent in 2013 whereas Thailand’s labor force working in this sector is relatively high with 39.1 per cent. Until now, Thailand has encountered difficulties that the number of labor force in agriculture sector has declined gradually. There are several reasons why farmers leave their lands. Beyond the realization of the agricultural importance towards the country economy, few joint initiatives were developed by joining forces in tackling such a thorny issue by supporting young people return to the farm land. Hence, this paper critically reviews the current joint-up development in changing agriculture situation in Thailand. In addition, it presents empirical evidence in sharing the developmental lessons learnt from collaborative forces from the public, private and the universities in re-shaping and training new style of professional young farmer.

1. Background:

1.1 Agriculture overview

Agriculture sector in the 21st century has been facing inevitable challenges, the climate change, the extension of bioenergy market, and the growing of world’s population. According to the United Nations (2013), the world population has projected an increase by almost one billion people within the next twelve years, from 7.2 billion in mid-2013 to 8.1 billion in 2025 and further increase to 10.9 billion by 2100 (see figure 1). These results are based on the medium-variant projection, which assumes a medium fertility.

.jpg)

Fig. 1. Population of the world, 1950-2100, according to different projections and variants

Source: United Nations (2013)

At the same time as population growth, world’s per capita food consumption is also growing, requiring 60 per cent more food must be produced by 2050 (Alexandratos and Bruinsma, 2012). Thailand could be referred as the Kitchen of the world. Table 1 illustrates Thailand is the world ranking agricultural products exporter. The commodities are cassava, sugar, fishery and rice (The Board of Investment of Thailand, 2013).

Table 1. The world ranking agricultural products exporter

.jpg)

Source: The Board of Investment of Thailand (2013).

1.2 Thailand Focus

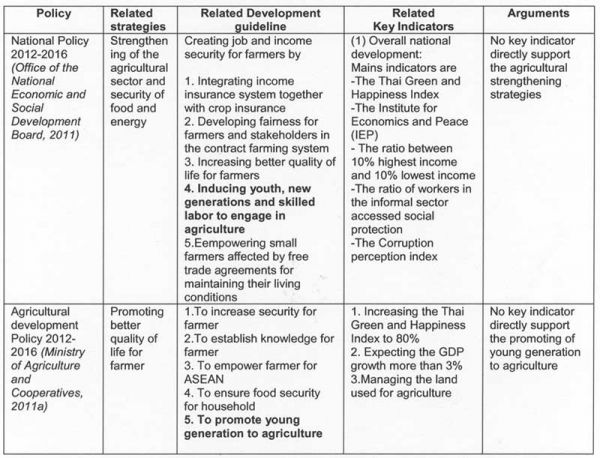

According to Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (2011), at national level, there are some strategies in relation to increase youth, new generations and skilled labor to engage in agriculture in Thailand. However, when the national plan was transformed into implementation, there are a few Key Indicators (KIs) especially no KPIs directly support the agricultural strengthening strategies (see Table 2).

Table 2. projects that the policy related to fostering the young into farming in Thailand

Over the past five decades, agricultural sector was the primary mechanism of economic growth in Thailand. In 1960, the agricultural value-share to GDP was higher than industrial sector, 32.1 per cent and 22.1 per cent respectively. The agricultural share in GDP has declined from 32.19 per cent in 1960 to 10.33 per cent in 2009. In contrast with the industrial value-share in GDP it has increased dramatically from 22.15 per cent in 1960 to 43.40 per cent in 2009. Therefore the agricultural share in GDP was smaller than industrial sector, 10.33 per cent and 43.40 per cent respectively (see Fig. 2).

.jpg)

Fig. 2. Sectorial Value-share (% of GDP)

Source: Suwannarat (2014)

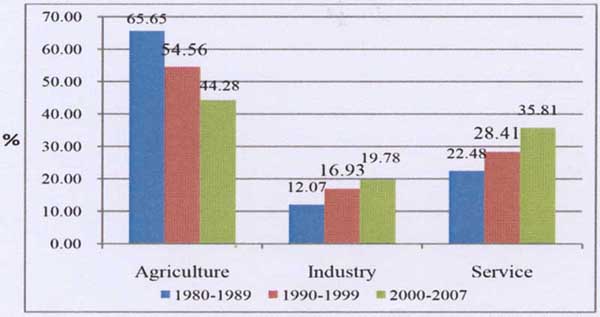

According to the National Statistical Office (2014), the amount of Thai farmer has deceased gradually since last 3 decades; decreasing from 65.65 per cent in 1980s to 44.28 per cent in 2000s (see Fig.3). Most of people leaving farm move to the service sector and some move to the industrial sector. Consequently, increasing the labor force in industrial sector from 12.07 per cent while increasing the labor force in service sector from 22.48 to 35.81 per cent. (see Fig.3).

Fig. 3. Sectorial Labor force

Source: Suwannarat, 2014

The table 3 illustrates that at present in 2013, agriculture values only about 8.3 per cent of GDP. Contrary to the macroeconomics, income from agriculture sector distribute to most of Thai population, since 39.1 per cent of Thailand’s labor force are engaged in agriculture sector (Bank of Thailand, 2014).

Table 3. Structure of the economy in 2013

.jpg)

*Financial, Education, Hotels and Restaurants, etc.

Source: Bank of Thailand, 2014.

According to the National Statistical Office (2014), the amount of Thai farmer has deceased gradually since last 2 decades (see Fig.3). In 1990s, 19 million peoples (63.4 per cent of total labor) work in agricultural sector; but in 2011s only 16.1 million peoples still working in farm (41.1 per cent). About 3 million peoples leave the farm, most of them go to service sector and some go to production sector (see Fig.4).

Significantly the Figure 4 shows that almost 3 million people have left farm within last 20 years. Unfortunately, young farmer and adulthood people flee the farm, left the old farmer behind. Specifically, the number of 15-24 years old farmer has decreased dramatically from 35.3 per cent to 12.1 per cent since 1987s to 2011s. In addition, the number of the adult hood has decreased from 34.7 per cent to 28.7 per cent. Contrasting with the proportion of old farmer, the number has increased gradually from 4.4 per cent to 12.4 per cent. At present, the average age of Thai farmer has been steadily on the rise is 51 years old (Thailand research fund, 2010).

.jpg)

Fig. 4. Labor force structure of agricultural sector

Source: Thailand Research Fund, 2010

2. Why did farmers leave their land?

The number of farmers leaving their farms increasing gradually due to reasons such as attitude (bad attitude), poverty (debt, have no land of their own) economics (low income, unreliable agricultural product price) and hardworking, the transition of agriculture to industrialize.

Attitude

Fundamentally, the study indicates that most of young people who grown up in farmer family do not want to be a farmer. In their perspective, a rice farmer, is a career that working hard in the field all day long but earn little money. It means farmer never can become rich. Their life value is driven by getting rich in a way. Consequently, they farming is not considered as a worthy-doing professions.

Furthermore, the second level of majority farmer thought that being a rice farmer indicates a lower social status in society. As a result, they attempted to retain their offspring away from the farm. Therefore, when their children face career choices, non-agricultural options are highly encouraged by the parents.

According to the Knowledge Network Institute of Thailand (2014), only 8.8 per cent students are shown in the university registrar majored in the agriculture program. In addition, farm work is perceived as hard labor work with unequal payment in Thailand.

Poverty

According to the Office of Agricultural Economics reported (2011), 29 per cent of farmer household gained the average income below the poverty line (592 USD per year). In 2011, the national Bureau of Statistics announced that about two out of three households of farmer had debt about 4,388 USD (Nuansoi and Penkleng, 2012). The low income and the debt caused the farmer and their descendant loss their interest in working on their farmland and move to another labor sector. 19.6 per cent of Thai farmer loss their farmland.

Production costs and Product prices

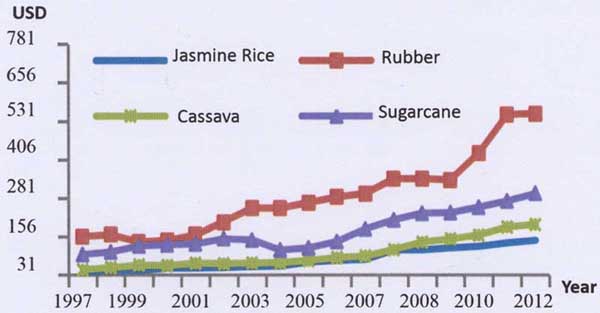

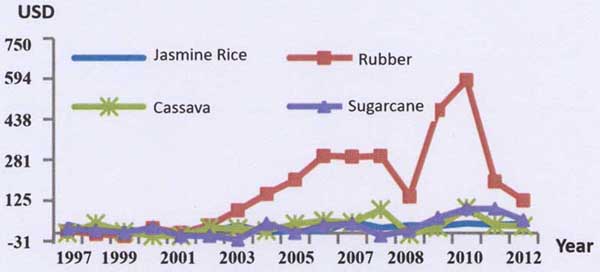

Another indication comes from uncertainty of revenue due to crop insurance system. No real intention to real support was discovered to support farmers. In addition, cost of operation is high, in contrast with the uncertain price of produces. Consequently, caused by seasonality issues and bad weather, the loss was tremendous and unpredictable (see Fig. 5a and 5b)

Fig. 5a. Total production cost of industrial crop

Source: Tunsri, 2011

Fig. 5b. Net income of industrial crop

Source: Tunsri, 2011

2.3 Roles of the public and the private sectors and universities in fostering the young into farming

Arguably, there are several sources of evidence that show the public sectors, the private sector and universities in fostering a joint force to encourage the young people back to farming sector in Thailand. Public and private sectors diagnosed the shortage of farmers which would cause problems of food safety, energy and export situation. Thus, public and private sector especially financial institutes have established several projects to encourage the society to be aware of and to cooperate for creating urgently the new generation of farmers. The new generation of farmers should have these characteristics as follows:

-

Mastery on learning on both new advanced technology from academic and local knowledge and integrate local knowledge and modern knowledge

-

Know how to manage to increase revenue and how to manage the cost and quality management. In addition they should know how to access their target group who demand their products and services

There are several sectors that drive the development of new generation of farmers. These sectors were classified into four groups (see fig.6) as follows:

I. Government agency

1. Ministry of Agriculture

1.1) Fishery Department

1.2) Department of Livestock Development

1.3) Agricultural Support Department

2. Ministry of Education

II. Private sector

1. Research Funding Institute

2. Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives

3. Private sector such as Kubota

4. Non-Profit Organizations

III. Academic Institute

1. University

2. Vocational College

IV. Research Unit

.jpg)

Fig. 6. Model of Integrated entities

Source: Agricultural Land Reform Office, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

There are several projects that these entities established such as New Farmer Development Project 2008-2012, School of Rice and Farmer, Volunteer Spirit Network, Smart farmer Smart officer and Rice camp.

Table 4a. Projects that the public and the private sectors and universities in fostering the young into farming in Thailand

.jpg)

MOAC = Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

ALRO = Agricultural Land Reform Office, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

BAAC = Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives

DOAE = Department of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

OHEC = Office of the Higher Education Commission

OHM = Office of His Majesty the King Principal Private Secretary

QLF = Quality Learning Founding

TRF = Thailand Research Fund

VEC = Office of Vocational Education Commission

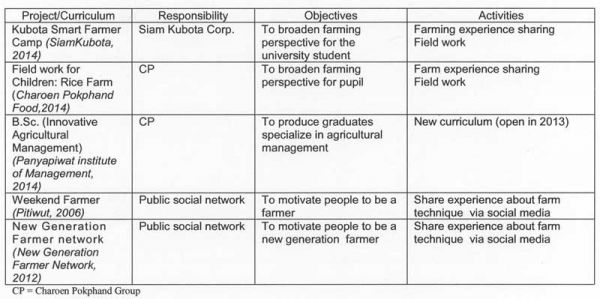

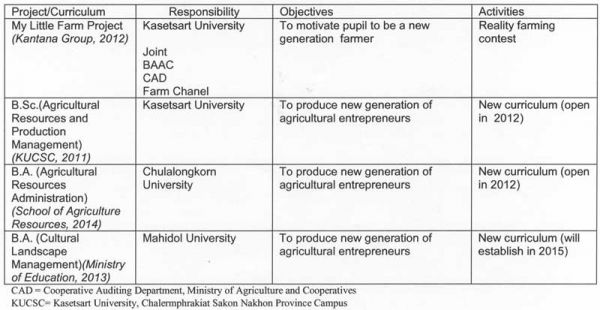

Table 4b. Projects that the private sectors in fostering the young into farming in Thailand

Table 4c. projects that the universities in fostering the young into farming in Thailand

It can be seen from the table 4a-c that there are several projects that the public, the private sectors and universities established such as New Farmer Development Project, School of Rice, Farmer Smart farmer Smart officer and Rice Camp. The authors present only a few significant projects. For instance, in terms of public sector, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives established “Smart Farmer Smart Officer Project”. The purposes are to initiate new generation by using data for making decision and to create smart officer to be consultancies for smart farmer. In addition, the Rice Department established “School of Rice and Farmer”. Its mission and function are prepare and develop training courses and rice, knowledge in all aspects of rice grain production chain, channels of learning and prepare the rice field demonstration, training system of rice in accordance with the development plan, Department rice effectiveness and network learning in rice through private sector education both formal and non-formal. There are several courses such as Intensive Professional Farmers, Course, the health drink made from rice, Initial course of farming, Intensive skin care from rice bran oil, Rice production course souvenirs and Course cooking and baking with rice. In terms of private sector, Charoen Pokphand Group founded its own university and has provided Bachelor of Science in Innovative Agricultural Management. In terms of university, there is the joint project called “My Little Farm Project”. It is the collaboration among Kasetsart University, Cooperative Auditing Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives and Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives. Objective is to inspire pupils to be a new generation farmer by using a reality farming contest.

Challenges for successful projects in a sustainable way

Agriculture sector has long served as the critical instrument of culture and economy in Thailand. As traditional agriculture has suffered from declining labor force, declining agriculture sector in GDP the country face challenges to revitalize renewed young professional farmers.

Regarding strategy, there are a few strategies in relation to promote youth, new generations and skilled labor to engage in agriculture. However, there is no key indicator directly supports the agricultural strengthening strategies in Thailand.

Realization the importance of the agriculture sector affecting their organizations by the public, private sectors and universities, several projects were established to promote youth into farming. In order to solve declining labor force in agriculture, these projects were created to inspire youth engaging agriculture sector.

In terms of the public sector, it can be seen obvious that the government has an intention to develop projects in the long term. For example, the project called “New Farmer Development Project” established by the Agricultural Land Reform Office (ALRO) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. ALRO give opportunity to new farmers to access the land and financial resources.

In terms of the private sector, as mentioned earlier, Charoen Pokphand (CP) Group opened courses such as Bachelor of Science in Innovative Agricultural Management. The students will complete their studies in 2016. Consequently, the number of agricultural entrepreneurs will increase.

In terms of universities, several universities in Thailand such as Kasetsart University, Chulalongkorn University and Mahidol University have opened new courses for producing agricultural entrepreneurs which will graduate in 2015 onward. For example, Kasetsart University opened new curriculum in Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Resources and Production Management. This course aims to produce agricultural entrepreneurs.

However, their goals have not been reached yet due to several difficulties such as unclear key indicators and loose integration among entities. Nevertheless we see a light at the end of the tunnel. Even most of these projects are at the preliminary stage but these can be counted as a good sign for agriculture sector. For example, the New Farmer Development Project was the joint project among the public, private and universities. All these entities have cooperated and carried out short and long term development planning to match the needs of industry. Hence, all entities should work closely together and recognize the potential of each other and make a commitment and take actions seriously to reach their goals. Therefore, it is the challenge for these entities to select the crucial mechanism and to cope with dynamic and limited resources.

CONCLUSION

Globalization has brought both opportunities and threats to the agriculture sector in Thailand; increasing population dramatically has pushed Thai Government to take intervention to change the condition and social structure of the farming industry. Radically, joint-up forces are encouraged by the Thai government in making a change environment to develop more young farmers for the next generation. The study demonstrated the important role being played by the joint institutional agents in the change process. Understanding the reasons why farmers have abandoned their farmer land is vital, however, study suggests a national level of collaborative strategic is needed to push this agenda further, not only stimulate the collaboration at national, regional, and local level but equally important to engage international players.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Associate Prof. Dr. Siree Chaiseri, Kasetsart University, Thailand and Dr. Chan-Ik Chun, Food and Fertilizer Technology Center. This paper was fund by the Rural Development Administration and the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center.

REFERENCES

Agricultural Land Reform Office. 2012. Special Project: Establishment and New Farmer Development Project. (http://eoffice.alro.go.th/agriculture/index.php?file=page&op= Newfarmers_bu; Accessed 20 July 2014).

Alexandratos, N. and J. Bruinsma. 2012. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050. Food and Agriculture Organization. Rome, Italy.

Bank of Thailand. 2014. Thailand at a glance. ( Http://www.bot.or.th/English/Economic

Conditions/Thai/genecon/Pages/Thailand_Glance.aspx; Accessed 30 August 2014).

Bureau of Cooperation and Promotion. 2013. (http://www.mua.go.th/users/bphe/bs/money. html, 20 August, 2014).

Committee of Smart Farmer and Smart Officer. 2013. Smart Farmer and Smart Officer. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation, Bangkok, Thailand.

Charoen Pokphand Food. 2014. News. (Http://www.cpfworldwide.com/th/media- center/news/view/69; Accessed 11 September, 2014).

Kantana Group. 2012. My Little Farm. (http://www.kantana.com/entertainment/index. php?option=com_ content&view category&id=14 &layout=blog&Itemid =27&limitstart=100;

Accessed September.2014)

Kasetsart University, Chalermphrakiat Sakon Nakhon Province Campus. 2011. Curriculum of Agricultural Resources and Production Management. Kasetsart University, Sakon

Nakhon, Thaiand.

Knowledge Network Institute of Thailand. 2014. Vision of Higher Education of Agriculture in Thailand. Bangkok, Thailand.

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. 2011a. Agricultural development Policy (2012-2016). Bangkok, Thailand.

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation. 2011b. Farmers Welfare Act. (Http://www.moac.go.th/ewt_news.php?nid=6136&filename=index; Accessed 10

September, 2014).

Ministry of Education. 2013. Mahidol University will open an agricultural entrepreneur course. (Http://www.en.moe.go.th/; Accessed 1 September, 2014).

National Economic and Social Development Board. 2011. The Eleventh National Economic and Social Development (2012-2016). Office of the Prime Minister, Bangkok, Thailand.

New Generation Farmer Network. 2012. New Generation Farmer Network. (Https://www.facebook.com/SinkhaKestr/info?ref=page_internal; Accessed 5 September, 2014).

Nuansoi, W. and S. Penkleng. 2012. A study of the socio-economics status of the farmer’s debt: case study of Ban Nong Mai Gan, Tha Chamuang, Rattaphum, Songkhla Province.

1st Mae Fah Luang University International Conference. Chiangrai, Thailand.

Panyapiwat institute of Management. 2014. Curriculum. (Http://www.pim.ac.th/#; Accessed 3 August, 2014).

Pitiwut, S. 2006. Weekend Farmer. (Https://www.facebook.com/WeekendFarmerNetworks/ inforef=page_interna l; Accessed 10 September.2014).

Rice department. 2013. School of Rice and Farmer. (Http://riceschool.ricethailand.go.th/; Accessed 20 August, 2014).

Rice Foundation. 2014. Rice camp. (Http://www.thairice.org/img/anu- 2557-poster.jpg; Accessed 10 September, 2014).

School of Agriculture Resources. 2010. Curriculum of School of Agriculture Resources. (Http://www.cusar.chula.ac.th/index.php/instructional; Accessed 20 September,

2014).

Siamkubota. 2014. Kubota smart farmer camp 2014. (Http://www.siamkubota.co.th/ kubotasmartfarmercamp2014/index.php; Accessed 2 September 201).

Suwannarat, P. 2014. Bank of Thailand: Agricultural Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Thailand. Ungraduated student, B. E. International Program, Faculty of Economics,

Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Thailand Research Fund. 2010. Special report: The Situation of Thai Farmers: The average of Thai famers is 45-51 years old and it was found out that 80% of Thai farmers is in

debt. (Http://www.trf.or.th/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id= 2772: 2010-08-21-11-32-59&catid=33&Itemid=357; Accessed 20 August 2014).

Thai Rice Organization. 2014. Rice Camp. (Http://www.thairice.org/imh/anu-2557- poster.jpg; Accessed 10 August, 2014).

The Board of Investment of Thailand. 2013. Industry Focus: Thailand, Food Exports Soaring. (Http://www.boi.go.th/tir/issue/201310_23_10/42.htm; Accessed, 10 September 2014).

Tunsri, K. 2011. Labor force and Agricultural sector changes. Bank of Thailand, North Eastern Branch, Khonkaen, Thailand.

United Nations. 2013. World Population Prospects The 2012 Revision: Key Finding and Advance Tables. New York.

Volunteer Spirit Network. 2013. Youth Volunteer Project for Learning Royal. (Http://www.volunteerspirit.org/event/6610; Accessed 9 September, 2014).

Young farmer development department. 2012. (Http://www.farmdev.doae.go.th/4-h.html; Accessed 21 August, 2014).

|

Submitted as a country paper for the FFTC-RDA International Seminar on Enhanced Entry of Young Generation into Farming, Oct. 20-24, Jeonju, Korea |

Entry of Young Generation into Farming in Thailand

Onanong Tapanapunnitikull and Siriluk Prasunpangsri2

lFaculty of Natural Resources and Agro Industry, Kasetsart University,

Chalermphrakiat Sakon Nakhon Province Campus, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand

2Faculty of Liberal Arts and Management Science, Kasetsart University,

Chalermphrakiat Sakon Nakhon Province Campus, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand

e-mail: csnslp@ku.ac.th

ABSTARCT

In the face of population growth, world’s per capita food consumption is also growing, requiring 60 per cent more food must be produced by 2050. Thailand could be referred as the Kitchen of the world, since Thailand is one of the world leaders in food exporter; the major commodities are cassava, sugar, fishery and rice. However, the labor force in agriculture sector has decreased gradually. In addition to unveil the reason for this decline, this paper examines the development of young farmers by institutional agents in Thailand the study illustrates the current situation and challenges of agriculture sector in Thailand. The empirical evidence suggests two attempts made by the different levels of collaboration. Firstly, efforts were taken amongst the public, private sectors and universities to encourage the young people reentry or reengage in agriculture sector. Secondly, national plan has put forward a strategy to stimulate/foster a new intake in agriculture sector. In addition, the study suggests ways to transform the national plan both at local and national level by considering short and long term tactics. Further suggestion is made to foster institutional level’s collaboration in enabling the implementation of the national strategy. Thus, this paper argues the condition for a paradigm shift in agriculture growth lies in cooperation strategically among all parties to achieve at local, national and regional level in the context of Thailand

Keywords: young farmers, agricultural development, cooperation, strategic management, agricultural entrepreneur

INTRODUCTION

Agriculture has long been important to Thailand development and has been viewed as “backbone” of Thailand. Over the past five decades, agricultural sector used to be the key engine of economic growth in Thailand. In 1960, the agricultural share in GDP was higher than industrial sector 32.1 per cent and 22.1 per cent respectively (Suwannarat, 2014). In 1961, the value of agriculture sector was about USD 781 million while the national GDP was USD 2,562 million (Ministry of Agriculture, 2011a). Nevertheless, the agricultural share in GDP has decreased dramatically to 8.3 percent in 2013 whereas Thailand’s labor force working in this sector is relatively high with 39.1 per cent. Until now, Thailand has encountered difficulties that the number of labor force in agriculture sector has declined gradually. There are several reasons why farmers leave their lands. Beyond the realization of the agricultural importance towards the country economy, few joint initiatives were developed by joining forces in tackling such a thorny issue by supporting young people return to the farm land. Hence, this paper critically reviews the current joint-up development in changing agriculture situation in Thailand. In addition, it presents empirical evidence in sharing the developmental lessons learnt from collaborative forces from the public, private and the universities in re-shaping and training new style of professional young farmer.

1. Background:

1.1 Agriculture overview

Agriculture sector in the 21st century has been facing inevitable challenges, the climate change, the extension of bioenergy market, and the growing of world’s population. According to the United Nations (2013), the world population has projected an increase by almost one billion people within the next twelve years, from 7.2 billion in mid-2013 to 8.1 billion in 2025 and further increase to 10.9 billion by 2100 (see figure 1). These results are based on the medium-variant projection, which assumes a medium fertility.

Fig. 1. Population of the world, 1950-2100, according to different projections and variants

Source: United Nations (2013)

At the same time as population growth, world’s per capita food consumption is also growing, requiring 60 per cent more food must be produced by 2050 (Alexandratos and Bruinsma, 2012). Thailand could be referred as the Kitchen of the world. Table 1 illustrates Thailand is the world ranking agricultural products exporter. The commodities are cassava, sugar, fishery and rice (The Board of Investment of Thailand, 2013).

Table 1. The world ranking agricultural products exporter

Source: The Board of Investment of Thailand (2013).

1.2 Thailand Focus

According to Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (2011), at national level, there are some strategies in relation to increase youth, new generations and skilled labor to engage in agriculture in Thailand. However, when the national plan was transformed into implementation, there are a few Key Indicators (KIs) especially no KPIs directly support the agricultural strengthening strategies (see Table 2).

Table 2. projects that the policy related to fostering the young into farming in Thailand

Over the past five decades, agricultural sector was the primary mechanism of economic growth in Thailand. In 1960, the agricultural value-share to GDP was higher than industrial sector, 32.1 per cent and 22.1 per cent respectively. The agricultural share in GDP has declined from 32.19 per cent in 1960 to 10.33 per cent in 2009. In contrast with the industrial value-share in GDP it has increased dramatically from 22.15 per cent in 1960 to 43.40 per cent in 2009. Therefore the agricultural share in GDP was smaller than industrial sector, 10.33 per cent and 43.40 per cent respectively (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Sectorial Value-share (% of GDP)

Source: Suwannarat (2014)

According to the National Statistical Office (2014), the amount of Thai farmer has deceased gradually since last 3 decades; decreasing from 65.65 per cent in 1980s to 44.28 per cent in 2000s (see Fig.3). Most of people leaving farm move to the service sector and some move to the industrial sector. Consequently, increasing the labor force in industrial sector from 12.07 per cent while increasing the labor force in service sector from 22.48 to 35.81 per cent. (see Fig.3).

Fig. 3. Sectorial Labor force

Source: Suwannarat, 2014

The table 3 illustrates that at present in 2013, agriculture values only about 8.3 per cent of GDP. Contrary to the macroeconomics, income from agriculture sector distribute to most of Thai population, since 39.1 per cent of Thailand’s labor force are engaged in agriculture sector (Bank of Thailand, 2014).

Table 3. Structure of the economy in 2013

*Financial, Education, Hotels and Restaurants, etc.

Source: Bank of Thailand, 2014.

According to the National Statistical Office (2014), the amount of Thai farmer has deceased gradually since last 2 decades (see Fig.3). In 1990s, 19 million peoples (63.4 per cent of total labor) work in agricultural sector; but in 2011s only 16.1 million peoples still working in farm (41.1 per cent). About 3 million peoples leave the farm, most of them go to service sector and some go to production sector (see Fig.4).

Significantly the Figure 4 shows that almost 3 million people have left farm within last 20 years. Unfortunately, young farmer and adulthood people flee the farm, left the old farmer behind. Specifically, the number of 15-24 years old farmer has decreased dramatically from 35.3 per cent to 12.1 per cent since 1987s to 2011s. In addition, the number of the adult hood has decreased from 34.7 per cent to 28.7 per cent. Contrasting with the proportion of old farmer, the number has increased gradually from 4.4 per cent to 12.4 per cent. At present, the average age of Thai farmer has been steadily on the rise is 51 years old (Thailand research fund, 2010).

Fig. 4. Labor force structure of agricultural sector

Source: Thailand Research Fund, 2010

2. Why did farmers leave their land?

The number of farmers leaving their farms increasing gradually due to reasons such as attitude (bad attitude), poverty (debt, have no land of their own) economics (low income, unreliable agricultural product price) and hardworking, the transition of agriculture to industrialize.

Attitude

Fundamentally, the study indicates that most of young people who grown up in farmer family do not want to be a farmer. In their perspective, a rice farmer, is a career that working hard in the field all day long but earn little money. It means farmer never can become rich. Their life value is driven by getting rich in a way. Consequently, they farming is not considered as a worthy-doing professions.

Furthermore, the second level of majority farmer thought that being a rice farmer indicates a lower social status in society. As a result, they attempted to retain their offspring away from the farm. Therefore, when their children face career choices, non-agricultural options are highly encouraged by the parents.

According to the Knowledge Network Institute of Thailand (2014), only 8.8 per cent students are shown in the university registrar majored in the agriculture program. In addition, farm work is perceived as hard labor work with unequal payment in Thailand.

Poverty

According to the Office of Agricultural Economics reported (2011), 29 per cent of farmer household gained the average income below the poverty line (592 USD per year). In 2011, the national Bureau of Statistics announced that about two out of three households of farmer had debt about 4,388 USD (Nuansoi and Penkleng, 2012). The low income and the debt caused the farmer and their descendant loss their interest in working on their farmland and move to another labor sector. 19.6 per cent of Thai farmer loss their farmland.

Production costs and Product prices

Another indication comes from uncertainty of revenue due to crop insurance system. No real intention to real support was discovered to support farmers. In addition, cost of operation is high, in contrast with the uncertain price of produces. Consequently, caused by seasonality issues and bad weather, the loss was tremendous and unpredictable (see Fig. 5a and 5b)

Fig. 5a. Total production cost of industrial crop

Source: Tunsri, 2011

Fig. 5b. Net income of industrial crop

Source: Tunsri, 2011

2.3 Roles of the public and the private sectors and universities in fostering the young into farming

Arguably, there are several sources of evidence that show the public sectors, the private sector and universities in fostering a joint force to encourage the young people back to farming sector in Thailand. Public and private sectors diagnosed the shortage of farmers which would cause problems of food safety, energy and export situation. Thus, public and private sector especially financial institutes have established several projects to encourage the society to be aware of and to cooperate for creating urgently the new generation of farmers. The new generation of farmers should have these characteristics as follows:

There are several sectors that drive the development of new generation of farmers. These sectors were classified into four groups (see fig.6) as follows:

I. Government agency

1. Ministry of Agriculture

1.1) Fishery Department

1.2) Department of Livestock Development

1.3) Agricultural Support Department

2. Ministry of Education

II. Private sector

1. Research Funding Institute

2. Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives

3. Private sector such as Kubota

4. Non-Profit Organizations

III. Academic Institute

1. University

2. Vocational College

IV. Research Unit

Fig. 6. Model of Integrated entities

Source: Agricultural Land Reform Office, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

There are several projects that these entities established such as New Farmer Development Project 2008-2012, School of Rice and Farmer, Volunteer Spirit Network, Smart farmer Smart officer and Rice camp.

Table 4a. Projects that the public and the private sectors and universities in fostering the young into farming in Thailand

MOAC = Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

ALRO = Agricultural Land Reform Office, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

BAAC = Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives

DOAE = Department of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives

OHEC = Office of the Higher Education Commission

OHM = Office of His Majesty the King Principal Private Secretary

QLF = Quality Learning Founding

TRF = Thailand Research Fund

VEC = Office of Vocational Education Commission

Table 4b. Projects that the private sectors in fostering the young into farming in Thailand

Table 4c. projects that the universities in fostering the young into farming in Thailand

It can be seen from the table 4a-c that there are several projects that the public, the private sectors and universities established such as New Farmer Development Project, School of Rice, Farmer Smart farmer Smart officer and Rice Camp. The authors present only a few significant projects. For instance, in terms of public sector, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives established “Smart Farmer Smart Officer Project”. The purposes are to initiate new generation by using data for making decision and to create smart officer to be consultancies for smart farmer. In addition, the Rice Department established “School of Rice and Farmer”. Its mission and function are prepare and develop training courses and rice, knowledge in all aspects of rice grain production chain, channels of learning and prepare the rice field demonstration, training system of rice in accordance with the development plan, Department rice effectiveness and network learning in rice through private sector education both formal and non-formal. There are several courses such as Intensive Professional Farmers, Course, the health drink made from rice, Initial course of farming, Intensive skin care from rice bran oil, Rice production course souvenirs and Course cooking and baking with rice. In terms of private sector, Charoen Pokphand Group founded its own university and has provided Bachelor of Science in Innovative Agricultural Management. In terms of university, there is the joint project called “My Little Farm Project”. It is the collaboration among Kasetsart University, Cooperative Auditing Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives and Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives. Objective is to inspire pupils to be a new generation farmer by using a reality farming contest.

Challenges for successful projects in a sustainable way

Agriculture sector has long served as the critical instrument of culture and economy in Thailand. As traditional agriculture has suffered from declining labor force, declining agriculture sector in GDP the country face challenges to revitalize renewed young professional farmers.

Regarding strategy, there are a few strategies in relation to promote youth, new generations and skilled labor to engage in agriculture. However, there is no key indicator directly supports the agricultural strengthening strategies in Thailand.

Realization the importance of the agriculture sector affecting their organizations by the public, private sectors and universities, several projects were established to promote youth into farming. In order to solve declining labor force in agriculture, these projects were created to inspire youth engaging agriculture sector.

In terms of the public sector, it can be seen obvious that the government has an intention to develop projects in the long term. For example, the project called “New Farmer Development Project” established by the Agricultural Land Reform Office (ALRO) under the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. ALRO give opportunity to new farmers to access the land and financial resources.

In terms of the private sector, as mentioned earlier, Charoen Pokphand (CP) Group opened courses such as Bachelor of Science in Innovative Agricultural Management. The students will complete their studies in 2016. Consequently, the number of agricultural entrepreneurs will increase.

In terms of universities, several universities in Thailand such as Kasetsart University, Chulalongkorn University and Mahidol University have opened new courses for producing agricultural entrepreneurs which will graduate in 2015 onward. For example, Kasetsart University opened new curriculum in Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Resources and Production Management. This course aims to produce agricultural entrepreneurs.

However, their goals have not been reached yet due to several difficulties such as unclear key indicators and loose integration among entities. Nevertheless we see a light at the end of the tunnel. Even most of these projects are at the preliminary stage but these can be counted as a good sign for agriculture sector. For example, the New Farmer Development Project was the joint project among the public, private and universities. All these entities have cooperated and carried out short and long term development planning to match the needs of industry. Hence, all entities should work closely together and recognize the potential of each other and make a commitment and take actions seriously to reach their goals. Therefore, it is the challenge for these entities to select the crucial mechanism and to cope with dynamic and limited resources.

CONCLUSION

Globalization has brought both opportunities and threats to the agriculture sector in Thailand; increasing population dramatically has pushed Thai Government to take intervention to change the condition and social structure of the farming industry. Radically, joint-up forces are encouraged by the Thai government in making a change environment to develop more young farmers for the next generation. The study demonstrated the important role being played by the joint institutional agents in the change process. Understanding the reasons why farmers have abandoned their farmer land is vital, however, study suggests a national level of collaborative strategic is needed to push this agenda further, not only stimulate the collaboration at national, regional, and local level but equally important to engage international players.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Associate Prof. Dr. Siree Chaiseri, Kasetsart University, Thailand and Dr. Chan-Ik Chun, Food and Fertilizer Technology Center. This paper was fund by the Rural Development Administration and the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center.

REFERENCES

Agricultural Land Reform Office. 2012. Special Project: Establishment and New Farmer Development Project. (http://eoffice.alro.go.th/agriculture/index.php?file=page&op= Newfarmers_bu; Accessed 20 July 2014).

Alexandratos, N. and J. Bruinsma. 2012. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050. Food and Agriculture Organization. Rome, Italy.

Bank of Thailand. 2014. Thailand at a glance. ( Http://www.bot.or.th/English/Economic

Conditions/Thai/genecon/Pages/Thailand_Glance.aspx; Accessed 30 August 2014).

Bureau of Cooperation and Promotion. 2013. (http://www.mua.go.th/users/bphe/bs/money. html, 20 August, 2014).

Committee of Smart Farmer and Smart Officer. 2013. Smart Farmer and Smart Officer. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation, Bangkok, Thailand.

Charoen Pokphand Food. 2014. News. (Http://www.cpfworldwide.com/th/media- center/news/view/69; Accessed 11 September, 2014).

Kantana Group. 2012. My Little Farm. (http://www.kantana.com/entertainment/index. php?option=com_ content&view category&id=14 &layout=blog&Itemid =27&limitstart=100;

Accessed September.2014)

Kasetsart University, Chalermphrakiat Sakon Nakhon Province Campus. 2011. Curriculum of Agricultural Resources and Production Management. Kasetsart University, Sakon

Nakhon, Thaiand.

Knowledge Network Institute of Thailand. 2014. Vision of Higher Education of Agriculture in Thailand. Bangkok, Thailand.

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. 2011a. Agricultural development Policy (2012-2016). Bangkok, Thailand.

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation. 2011b. Farmers Welfare Act. (Http://www.moac.go.th/ewt_news.php?nid=6136&filename=index; Accessed 10

September, 2014).

Ministry of Education. 2013. Mahidol University will open an agricultural entrepreneur course. (Http://www.en.moe.go.th/; Accessed 1 September, 2014).

National Economic and Social Development Board. 2011. The Eleventh National Economic and Social Development (2012-2016). Office of the Prime Minister, Bangkok, Thailand.

New Generation Farmer Network. 2012. New Generation Farmer Network. (Https://www.facebook.com/SinkhaKestr/info?ref=page_internal; Accessed 5 September, 2014).

Nuansoi, W. and S. Penkleng. 2012. A study of the socio-economics status of the farmer’s debt: case study of Ban Nong Mai Gan, Tha Chamuang, Rattaphum, Songkhla Province.

1st Mae Fah Luang University International Conference. Chiangrai, Thailand.

Panyapiwat institute of Management. 2014. Curriculum. (Http://www.pim.ac.th/#; Accessed 3 August, 2014).

Pitiwut, S. 2006. Weekend Farmer. (Https://www.facebook.com/WeekendFarmerNetworks/ inforef=page_interna l; Accessed 10 September.2014).

Rice department. 2013. School of Rice and Farmer. (Http://riceschool.ricethailand.go.th/; Accessed 20 August, 2014).

Rice Foundation. 2014. Rice camp. (Http://www.thairice.org/img/anu- 2557-poster.jpg; Accessed 10 September, 2014).

School of Agriculture Resources. 2010. Curriculum of School of Agriculture Resources. (Http://www.cusar.chula.ac.th/index.php/instructional; Accessed 20 September,

2014).

Siamkubota. 2014. Kubota smart farmer camp 2014. (Http://www.siamkubota.co.th/ kubotasmartfarmercamp2014/index.php; Accessed 2 September 201).

Suwannarat, P. 2014. Bank of Thailand: Agricultural Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Thailand. Ungraduated student, B. E. International Program, Faculty of Economics,

Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Thailand Research Fund. 2010. Special report: The Situation of Thai Farmers: The average of Thai famers is 45-51 years old and it was found out that 80% of Thai farmers is in

debt. (Http://www.trf.or.th/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id= 2772: 2010-08-21-11-32-59&catid=33&Itemid=357; Accessed 20 August 2014).

Thai Rice Organization. 2014. Rice Camp. (Http://www.thairice.org/imh/anu-2557- poster.jpg; Accessed 10 August, 2014).

The Board of Investment of Thailand. 2013. Industry Focus: Thailand, Food Exports Soaring. (Http://www.boi.go.th/tir/issue/201310_23_10/42.htm; Accessed, 10 September 2014).

Tunsri, K. 2011. Labor force and Agricultural sector changes. Bank of Thailand, North Eastern Branch, Khonkaen, Thailand.

United Nations. 2013. World Population Prospects The 2012 Revision: Key Finding and Advance Tables. New York.

Volunteer Spirit Network. 2013. Youth Volunteer Project for Learning Royal. (Http://www.volunteerspirit.org/event/6610; Accessed 9 September, 2014).

Young farmer development department. 2012. (Http://www.farmdev.doae.go.th/4-h.html; Accessed 21 August, 2014).