ABSTRACT

Non-farm households with regular membership in agricultural cooperatives continue to increase in Japan. This helps agricultural cooperatives earn profits by selling financial instruments to non-farm households, without which agricultural cooperatives cannot sustain themselves. However, a persisting problem is cases in which non-farm households illegally hold regular membership in agricultural cooperatives, making it difficult for agricultural cooperatives to maintain their identity as an agricultural group.

Keywords: agricultural association, associate membership, banking and insurance businesses, non-farm household, regular membership

INTRODUCTION

Japan’s agricultural cooperatives have adopted a nationwide system. Their offices, which are in direct contact with farm households, are called unit cooperatives. Unit cooperatives form a national federation called the National Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives (NFAC). Almost all Japan’s farm households join agricultural cooperatives as regular members of unit cooperatives.

While the total number of farm households has been decreasing for over 50 years, the number of non-farm households that hold regular membership in unit cooperatives has been increasing[1]. Consequently, nearly half of the regular members of unit cooperatives are non-farm households.

Why are non-farm households becoming the majority in unit cooperatives? What is the role of non-farm households in unit cooperatives’ activities? By answering these questions, this paper describes the changing status of Japan’s agricultural cooperatives.

THE HISTORY OF JAPAN’S AGRICULTURAL COOPERATIVES

The predecessor of agricultural cooperatives was the Agricultural Association (AA), which was established as part of Japan’s general mobilization during the Pacific War. The AA formed a two-layered structure: a local office at each municipality and a federation called the National Economic Federation of Agricultural Association (NEFAA) at the national level. Each farm household was obliged to belong to a local office in its residency.

AA oversaw controlling markets for agricultural inputs and products on a war footing. Each local AA office collected agricultural products from farm households and supplied them to the government through the NEFAA. In addition, the NEFAA procured agricultural inputs from factories and distributed them to farm households through local AA offices.

In 1945, the principal victorious nations of the Pacific War established the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ) in Tokyo as the absolute ruler of Japan. The GHQ was in power until the San Francisco Peace Treaty became effective in April 1952. The GHQ was aware that the AA’s control of markets of agricultural inputs and products should continue because Japan was seriously suffering from food shortages. Simultaneously, the GHQ was responsible for civilizing Japanese society. This created a dilemma for the GHQ. On the one hand, the GHQ wanted to dissolve the AA because it was established under military administration. On the other hand, the GHQ needed some organization to control the markets for agricultural inputs and products. As a solution to this dilemma, the GHQ reformed the AA into agricultural cooperatives. In 1947, under the supervision of the GHQ, the Agricultural Cooperative Act (ACA) was established and the AA was dissolved[2]. Municipalities’ local AA offices were reformed into unit cooperatives. Unit cooperatives succeeded local AA offices’ role of distributing agricultural inputs to and collecting agricultural products from farm households. Each unit cooperative had its own memorandum. Jurisdictions did not overlap among unit cooperatives. The NEFAA was reformed and separated into two bodies: the National Federation for Joint Purchase of Agricultural Cooperatives (NFJPAC), which succeeded the NEFAA’s task of distributing agricultural inputs, and the National Federation for Joint Shipment of Agricultural Cooperatives (NFJSAC), which succeeded the NEFAA’s task of collecting agricultural products.

As the shortage of agricultural inputs and products was mitigated by the recovery of Japan’s economy from war damage, Japan’s government liberalized the trade of agricultural inputs and products in 1951. Since then, competing with agribusiness companies and collaborating with the NFJSAC and NFJPAS, unit cooperatives have been engaged in the joint purchase of agricultural inputs and the joint shipment of agricultural products. The NFJPAC and NFJSAC merged into the NFAC in 1972. The remainder of Japan’s agricultural cooperative system remains unchanged.

Although the ACA does not impose any legal obligations on farm households to join unit cooperatives, almost all farm households do so. This is because, as discussed in details below, unit cooperatives’ activities cover a broad range of fields in local life.

BUSINESSES OF UNIT COOPERATIVES

The ACA allows unit cooperatives to perform various types of businesses such as agricultural businesses (e.g., joint shipment of agricultural products, joint purchase of farm inputs, joint use of agricultural warehouses, and agricultural development and extension) and non-agricultural businesses (e.g., supermarkets, banking, life insurance, and travel agencies). Unit cooperatives provide so many types of businesses that they are often nicknamed “local-specific general trading companies.”

Notably, Japan’s government prohibits non-financial bodies from banking and insurance services. However, as an exception, agricultural cooperatives have the privilege to conduct banking and insurance services.

Another privilege given to agricultural cooperatives is exemption from the Antimonopoly Act[3]. This means that, even if all farm households in the jurisdiction of a unit cooperative do not ship any agricultural products other than the unit cooperative, it is not recognized as unfair if the unit cooperative does not disturb other agribusiness companies in the jurisdiction.

TYPES OF UNIT COOPERATIVE MEMBERSHIPS

There are two types of membership in unit cooperatives: regular and associate membership. Both types of members have equal rights to use the services provided by unit cooperatives. However, only regular members have the right to vote at general meetings, wherein unit cooperatives make the most important decisions about their activities. In principle, only those who are engaged in farming are qualified to be regular members (however, as will be discussed in detail later, there are many loopholes in this qualification principle). Those who show sympathy for the cooperative movement (regardless of whether they are engaged in farming) are allowed to join the unit cooperatives as associates.

Each unit cooperative can set further requirements for regular or associate membership by stipulating these in its memorandum. For example, many unit cooperatives do not assign associate memberships to those who do not live in their jurisdictions.

The ACA allows not only farm households, but also legal persons engaged in farming (e.g., corporations, cooperatives, and incorporated foundations) to be regular members of unit cooperatives. Theoretically, cooperatives (not only agricultural cooperatives but also fishermen’s, small and medium-sized enterprises, and consumer cooperatives) exist to protect small producers’ or consumers’ benefits by promoting mutual assistance among themselves. Thus, the ACA prohibits large legal persons—those who employ over 300 permanent workers and are capitalized at over JPY300 million (nearly US$2 milliom)—from being regular members of unit cooperatives. However, the ACA does not have such a prohibition for associate membership. In addition, the ACA allows legal persons who are not engaged in farming to be associate members of unit cooperatives. Unless unit cooperatives impose additional regulations on associate membership in their memorandums, large legal persons (regardless of whether they are engaged in farming) can also obtain associate memberships of unit cooperatives. As agricultural cooperatives are outside the scope of the Antimonopoly Act, as mentioned above, it is technically possible for large companies to escape the Act by obtaining associate membership of unit cooperatives.

PROFITABILITY OF UNIT COOPERATIVES’ BUSINESSES

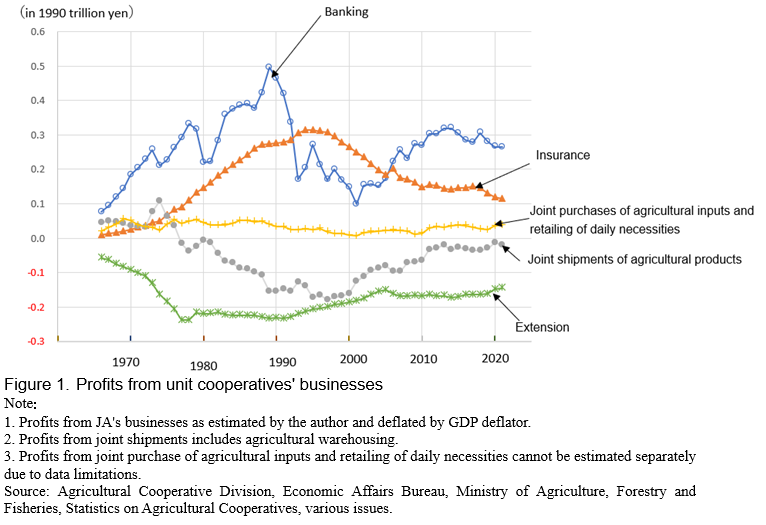

Japan’s government provides detailed information on unit cooperatives’ business performance on the website under the title “Statistics on Agricultural Cooperatives (SAC)”[4]. Thus, the profitability of unit cooperatives’ businesses can be estimated. As shown in Figure 1, while unit cooperatives lose money in agriculture-related businesses such as extension and joint shipment, they earn money in financial businesses such as banking and insurance.

Notably, unit cooperatives’ banking and insurance services are primarily for non-agricultural purposes. According to the SAC, unit cooperatives hold JPY109.3 trillion (nearly US$730 million) in deposits from farmers and non-farmers (average month-end balance for the 2021 business year). Approximately JPY80.5 trillion (nearly US$540 million) is redeposited to other financial institutions. While unit cooperatives loan JPY19.6 trillion (nearly US$130 million) to regular and associate members, most of these loans are for non-agricultural purposes such as constructing buildings and houses (farmland is often converted to buildings and houses). Unit cooperatives’ insurance is also for non-agricultural purposes, such as fire insurance for residences.

NON-FARM HOUSEHOLDS WITH REGULAR MEMBERSHIP IN UNIT COOPERATIVES

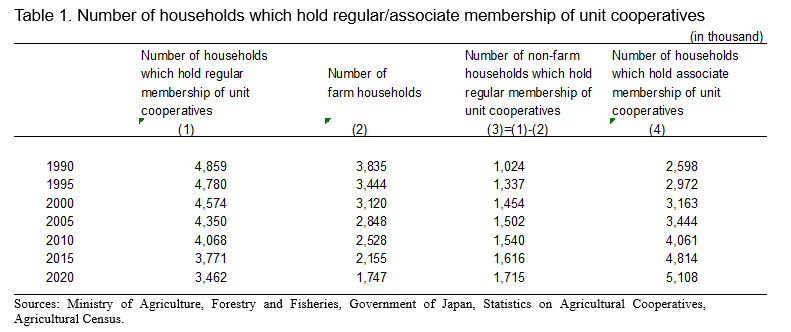

The SAC provides the total number of households that hold regular memberships in unit cooperatives. Simultaneously, based on the agricultural census, which is conducted every five years, Japan’s government publishes estimates of the total number of farm households. As mentioned above, only those engaged in farming are qualified to hold regular membership in unit cooperatives. This implies that the total number of households with regular membership should not exceed the total number of farm households. However, Table 1 shows that households that hold regular memberships in unit cooperatives outnumber farm households. This means at least 1.7 million households joined unit cooperatives as regular members, despite not being engaged in farming[5].

There are three ways for non-farm households to obtain regular membership in unit cooperatives:

- Differences in the definition of farm households

In the agricultural census, Japan’s government defines a farm household as a household that has cultivated land of 0.1 ha or more or that has sold over JPY150 thousand (nearly US$1,000) of agricultural products in a year. However, unit cooperatives are not required to follow Japan’s government’s definition in this matter. Typically, even 0.1 ha is too small to be regarded as a farm household. Thus, it is questionable whether unit cooperatives should provide regular memberships to those who do not satisfy Japan’s government’s definition of farm households.

- Special program allowing regular membership for non-farmers

The ACA stipulates that, if a regular member quits farming by selling or renting out all their farmland, based on the Act on Promotion of Improvement of Agricultural Management Foundation (APIAMF), regular membership can be maintained even if the member is no longer engaged in farming. However, whether this stipulation is reasonable remains debatable. When quitting farming, farmland is usually sold or rented out on the legal basis of the Agricultural Land Act (rather than the APIAMF).

- Illegal treatment of those who leave farming

The ACA stipulates that, if a regular member quits farming based on the Agricultural Land Act, their regular membership ceases to be valid. However, it is unclear whether this stipulation is strictly observed. Unit cooperatives do not usually inspect whether members satisfy the requirements for regular membership.

There is no official survey of non-farm households that hold regular memberships in unit cooperatives. The author estimates that (iii) accounts for most of the gap between the total number of farm households and that of total households that hold regular membership in unit cooperatives[6]. As the total number of farm households in Japan continues to decline, the significance of non-farm households in unit cooperatives is expected to continue to increase.

UNIT COOPERATIVES’ PROBLEMS IN EARNING PROFITS

As mentioned previously, banking and insurance services, which are not directly related to agriculture, account for most of the unit cooperatives’ profits. Unit cooperatives sell financial instruments to local households regardless of whether they are engaged in farming. This makes unit cooperatives reluctant to deprive those who quit farming of their regular membership.

Unit cooperatives also actively invite non-farm households to join as associate members and attempt to sell them financial instruments. The presidents of unit cooperatives, elected by regular members, are usually better politicians than businesspeople. Thus, they tend to adopt a simple, old-fashioned way of earning profits: they set a target amounts of deposits and insurance policies for each employee[7].

Access to financial institutions in rural areas was limited when the ACA was established. Therefore, only agricultural cooperatives were allowed to provide banking and insurance services. However, at present, financial institutions compete with each other, even in rural areas. Occasionally, employees in unit cooperatives are pressured to spend their own money to reach their quotas (otherwise, they are forced to resign). In the first half of 2023, regarding this pressure as psychological abuse at work, major weekly journals and newspapers, such as Weekly Shincho and Chunichi Shimbun, launched a series of case-study based articles against unit cooperatives. In August 2023, the government issued a new guideline whereby the executives (including presidents) of unit cooperatives are discouraged from allocating tough quotas to their employees. However, it is uncertain whether this new guideline is effective in improving unit cooperatives’ business style, because it is difficult for the government to maintain surveillance over unit cooperatives.

CONCLUSION

Japan’s agricultural cooperatives are privileged to be an exception to Japan’s government’s principle that non-financial economic bodies should not engage in banking and insurance businesses. Unit cooperatives can sustain themselves owing to this privilege. As most unit cooperatives’ financial instruments are not related to agriculture, they want to keep non-farm households as regular or associate members. However, this contradicts the identity of agricultural cooperatives as an agricultural group.

REFERENCES

Godo, Y. “The Treatment of Agricultural Cooperatives in the Antimonopoly Act in Japan.” FFTC Agricultural Policy Database (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region). November 30, 2015.

Godo, Y. “Case Study of Unfair Practices by a Japanese Agricultural Cooperative,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Database (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region). January 1, 2016.

Mulgan, A. G., The Politics of Agriculture in Japan. Routledge, 2000.

[1] According to the Agricultural Census, which is conducted every five years, the total number of farm households peaked at 6.1 million in 1960. This number decreased to 1.7 million by 2020.

[2] An “agricultural cooperative” refers to a voluntary organization among farmers for mutual support. The ACA allows any farmer group to voluntarily establish its own agricultural cooperative. However, in reality, Japan’s agricultural cooperatives were established under the strong guidance of the government.

[3] Godo (2015, 2016) discuss the relationship between the ACA and the Antimonopoly Act in detail.

[5] Some farm households do not belong to any unit cooperative (while most farm households belong to unit cooperatives). Thus, Table 1 has a lower bias in estimating the total number of non-farm households with regular membership in unit cooperatives.

[6] This estimate bases on the author’s informal interview with top officials of unit cooperatives.

[7] Mulgan (2000) discusses details of unit cooperatives’ strategy.

Japanese Agricultural Cooperatives’ Weakening Identity as an Agricultural Group

ABSTRACT

Non-farm households with regular membership in agricultural cooperatives continue to increase in Japan. This helps agricultural cooperatives earn profits by selling financial instruments to non-farm households, without which agricultural cooperatives cannot sustain themselves. However, a persisting problem is cases in which non-farm households illegally hold regular membership in agricultural cooperatives, making it difficult for agricultural cooperatives to maintain their identity as an agricultural group.

Keywords: agricultural association, associate membership, banking and insurance businesses, non-farm household, regular membership

INTRODUCTION

Japan’s agricultural cooperatives have adopted a nationwide system. Their offices, which are in direct contact with farm households, are called unit cooperatives. Unit cooperatives form a national federation called the National Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives (NFAC). Almost all Japan’s farm households join agricultural cooperatives as regular members of unit cooperatives.

While the total number of farm households has been decreasing for over 50 years, the number of non-farm households that hold regular membership in unit cooperatives has been increasing[1]. Consequently, nearly half of the regular members of unit cooperatives are non-farm households.

Why are non-farm households becoming the majority in unit cooperatives? What is the role of non-farm households in unit cooperatives’ activities? By answering these questions, this paper describes the changing status of Japan’s agricultural cooperatives.

THE HISTORY OF JAPAN’S AGRICULTURAL COOPERATIVES

The predecessor of agricultural cooperatives was the Agricultural Association (AA), which was established as part of Japan’s general mobilization during the Pacific War. The AA formed a two-layered structure: a local office at each municipality and a federation called the National Economic Federation of Agricultural Association (NEFAA) at the national level. Each farm household was obliged to belong to a local office in its residency.

AA oversaw controlling markets for agricultural inputs and products on a war footing. Each local AA office collected agricultural products from farm households and supplied them to the government through the NEFAA. In addition, the NEFAA procured agricultural inputs from factories and distributed them to farm households through local AA offices.

In 1945, the principal victorious nations of the Pacific War established the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ) in Tokyo as the absolute ruler of Japan. The GHQ was in power until the San Francisco Peace Treaty became effective in April 1952. The GHQ was aware that the AA’s control of markets of agricultural inputs and products should continue because Japan was seriously suffering from food shortages. Simultaneously, the GHQ was responsible for civilizing Japanese society. This created a dilemma for the GHQ. On the one hand, the GHQ wanted to dissolve the AA because it was established under military administration. On the other hand, the GHQ needed some organization to control the markets for agricultural inputs and products. As a solution to this dilemma, the GHQ reformed the AA into agricultural cooperatives. In 1947, under the supervision of the GHQ, the Agricultural Cooperative Act (ACA) was established and the AA was dissolved[2]. Municipalities’ local AA offices were reformed into unit cooperatives. Unit cooperatives succeeded local AA offices’ role of distributing agricultural inputs to and collecting agricultural products from farm households. Each unit cooperative had its own memorandum. Jurisdictions did not overlap among unit cooperatives. The NEFAA was reformed and separated into two bodies: the National Federation for Joint Purchase of Agricultural Cooperatives (NFJPAC), which succeeded the NEFAA’s task of distributing agricultural inputs, and the National Federation for Joint Shipment of Agricultural Cooperatives (NFJSAC), which succeeded the NEFAA’s task of collecting agricultural products.

As the shortage of agricultural inputs and products was mitigated by the recovery of Japan’s economy from war damage, Japan’s government liberalized the trade of agricultural inputs and products in 1951. Since then, competing with agribusiness companies and collaborating with the NFJSAC and NFJPAS, unit cooperatives have been engaged in the joint purchase of agricultural inputs and the joint shipment of agricultural products. The NFJPAC and NFJSAC merged into the NFAC in 1972. The remainder of Japan’s agricultural cooperative system remains unchanged.

Although the ACA does not impose any legal obligations on farm households to join unit cooperatives, almost all farm households do so. This is because, as discussed in details below, unit cooperatives’ activities cover a broad range of fields in local life.

BUSINESSES OF UNIT COOPERATIVES

The ACA allows unit cooperatives to perform various types of businesses such as agricultural businesses (e.g., joint shipment of agricultural products, joint purchase of farm inputs, joint use of agricultural warehouses, and agricultural development and extension) and non-agricultural businesses (e.g., supermarkets, banking, life insurance, and travel agencies). Unit cooperatives provide so many types of businesses that they are often nicknamed “local-specific general trading companies.”

Notably, Japan’s government prohibits non-financial bodies from banking and insurance services. However, as an exception, agricultural cooperatives have the privilege to conduct banking and insurance services.

Another privilege given to agricultural cooperatives is exemption from the Antimonopoly Act[3]. This means that, even if all farm households in the jurisdiction of a unit cooperative do not ship any agricultural products other than the unit cooperative, it is not recognized as unfair if the unit cooperative does not disturb other agribusiness companies in the jurisdiction.

TYPES OF UNIT COOPERATIVE MEMBERSHIPS

There are two types of membership in unit cooperatives: regular and associate membership. Both types of members have equal rights to use the services provided by unit cooperatives. However, only regular members have the right to vote at general meetings, wherein unit cooperatives make the most important decisions about their activities. In principle, only those who are engaged in farming are qualified to be regular members (however, as will be discussed in detail later, there are many loopholes in this qualification principle). Those who show sympathy for the cooperative movement (regardless of whether they are engaged in farming) are allowed to join the unit cooperatives as associates.

Each unit cooperative can set further requirements for regular or associate membership by stipulating these in its memorandum. For example, many unit cooperatives do not assign associate memberships to those who do not live in their jurisdictions.

The ACA allows not only farm households, but also legal persons engaged in farming (e.g., corporations, cooperatives, and incorporated foundations) to be regular members of unit cooperatives. Theoretically, cooperatives (not only agricultural cooperatives but also fishermen’s, small and medium-sized enterprises, and consumer cooperatives) exist to protect small producers’ or consumers’ benefits by promoting mutual assistance among themselves. Thus, the ACA prohibits large legal persons—those who employ over 300 permanent workers and are capitalized at over JPY300 million (nearly US$2 milliom)—from being regular members of unit cooperatives. However, the ACA does not have such a prohibition for associate membership. In addition, the ACA allows legal persons who are not engaged in farming to be associate members of unit cooperatives. Unless unit cooperatives impose additional regulations on associate membership in their memorandums, large legal persons (regardless of whether they are engaged in farming) can also obtain associate memberships of unit cooperatives. As agricultural cooperatives are outside the scope of the Antimonopoly Act, as mentioned above, it is technically possible for large companies to escape the Act by obtaining associate membership of unit cooperatives.

PROFITABILITY OF UNIT COOPERATIVES’ BUSINESSES

Japan’s government provides detailed information on unit cooperatives’ business performance on the website under the title “Statistics on Agricultural Cooperatives (SAC)”[4]. Thus, the profitability of unit cooperatives’ businesses can be estimated. As shown in Figure 1, while unit cooperatives lose money in agriculture-related businesses such as extension and joint shipment, they earn money in financial businesses such as banking and insurance.

Notably, unit cooperatives’ banking and insurance services are primarily for non-agricultural purposes. According to the SAC, unit cooperatives hold JPY109.3 trillion (nearly US$730 million) in deposits from farmers and non-farmers (average month-end balance for the 2021 business year). Approximately JPY80.5 trillion (nearly US$540 million) is redeposited to other financial institutions. While unit cooperatives loan JPY19.6 trillion (nearly US$130 million) to regular and associate members, most of these loans are for non-agricultural purposes such as constructing buildings and houses (farmland is often converted to buildings and houses). Unit cooperatives’ insurance is also for non-agricultural purposes, such as fire insurance for residences.

NON-FARM HOUSEHOLDS WITH REGULAR MEMBERSHIP IN UNIT COOPERATIVES

The SAC provides the total number of households that hold regular memberships in unit cooperatives. Simultaneously, based on the agricultural census, which is conducted every five years, Japan’s government publishes estimates of the total number of farm households. As mentioned above, only those engaged in farming are qualified to hold regular membership in unit cooperatives. This implies that the total number of households with regular membership should not exceed the total number of farm households. However, Table 1 shows that households that hold regular memberships in unit cooperatives outnumber farm households. This means at least 1.7 million households joined unit cooperatives as regular members, despite not being engaged in farming[5].

There are three ways for non-farm households to obtain regular membership in unit cooperatives:

In the agricultural census, Japan’s government defines a farm household as a household that has cultivated land of 0.1 ha or more or that has sold over JPY150 thousand (nearly US$1,000) of agricultural products in a year. However, unit cooperatives are not required to follow Japan’s government’s definition in this matter. Typically, even 0.1 ha is too small to be regarded as a farm household. Thus, it is questionable whether unit cooperatives should provide regular memberships to those who do not satisfy Japan’s government’s definition of farm households.

The ACA stipulates that, if a regular member quits farming by selling or renting out all their farmland, based on the Act on Promotion of Improvement of Agricultural Management Foundation (APIAMF), regular membership can be maintained even if the member is no longer engaged in farming. However, whether this stipulation is reasonable remains debatable. When quitting farming, farmland is usually sold or rented out on the legal basis of the Agricultural Land Act (rather than the APIAMF).

The ACA stipulates that, if a regular member quits farming based on the Agricultural Land Act, their regular membership ceases to be valid. However, it is unclear whether this stipulation is strictly observed. Unit cooperatives do not usually inspect whether members satisfy the requirements for regular membership.

There is no official survey of non-farm households that hold regular memberships in unit cooperatives. The author estimates that (iii) accounts for most of the gap between the total number of farm households and that of total households that hold regular membership in unit cooperatives[6]. As the total number of farm households in Japan continues to decline, the significance of non-farm households in unit cooperatives is expected to continue to increase.

UNIT COOPERATIVES’ PROBLEMS IN EARNING PROFITS

As mentioned previously, banking and insurance services, which are not directly related to agriculture, account for most of the unit cooperatives’ profits. Unit cooperatives sell financial instruments to local households regardless of whether they are engaged in farming. This makes unit cooperatives reluctant to deprive those who quit farming of their regular membership.

Unit cooperatives also actively invite non-farm households to join as associate members and attempt to sell them financial instruments. The presidents of unit cooperatives, elected by regular members, are usually better politicians than businesspeople. Thus, they tend to adopt a simple, old-fashioned way of earning profits: they set a target amounts of deposits and insurance policies for each employee[7].

Access to financial institutions in rural areas was limited when the ACA was established. Therefore, only agricultural cooperatives were allowed to provide banking and insurance services. However, at present, financial institutions compete with each other, even in rural areas. Occasionally, employees in unit cooperatives are pressured to spend their own money to reach their quotas (otherwise, they are forced to resign). In the first half of 2023, regarding this pressure as psychological abuse at work, major weekly journals and newspapers, such as Weekly Shincho and Chunichi Shimbun, launched a series of case-study based articles against unit cooperatives. In August 2023, the government issued a new guideline whereby the executives (including presidents) of unit cooperatives are discouraged from allocating tough quotas to their employees. However, it is uncertain whether this new guideline is effective in improving unit cooperatives’ business style, because it is difficult for the government to maintain surveillance over unit cooperatives.

CONCLUSION

Japan’s agricultural cooperatives are privileged to be an exception to Japan’s government’s principle that non-financial economic bodies should not engage in banking and insurance businesses. Unit cooperatives can sustain themselves owing to this privilege. As most unit cooperatives’ financial instruments are not related to agriculture, they want to keep non-farm households as regular or associate members. However, this contradicts the identity of agricultural cooperatives as an agricultural group.

REFERENCES

Godo, Y. “The Treatment of Agricultural Cooperatives in the Antimonopoly Act in Japan.” FFTC Agricultural Policy Database (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region). November 30, 2015.

Godo, Y. “Case Study of Unfair Practices by a Japanese Agricultural Cooperative,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Database (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region). January 1, 2016.

Mulgan, A. G., The Politics of Agriculture in Japan. Routledge, 2000.

[1] According to the Agricultural Census, which is conducted every five years, the total number of farm households peaked at 6.1 million in 1960. This number decreased to 1.7 million by 2020.

[2] An “agricultural cooperative” refers to a voluntary organization among farmers for mutual support. The ACA allows any farmer group to voluntarily establish its own agricultural cooperative. However, in reality, Japan’s agricultural cooperatives were established under the strong guidance of the government.

[3] Godo (2015, 2016) discuss the relationship between the ACA and the Antimonopoly Act in detail.

[4] https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/noukyo_rengokai/index.html.

[5] Some farm households do not belong to any unit cooperative (while most farm households belong to unit cooperatives). Thus, Table 1 has a lower bias in estimating the total number of non-farm households with regular membership in unit cooperatives.

[6] This estimate bases on the author’s informal interview with top officials of unit cooperatives.

[7] Mulgan (2000) discusses details of unit cooperatives’ strategy.