ABSTRACT

Several reforms were brought in through several amendments in the Tea Marketing Control 2003 to safeguard the Small Tea Growers (STGs) from the prolonged price crisis. The green leaf tea prices for the last decade hovering around US$ 0.10 to 0.18/ kg (INR 82/US$), which is far below the cost of production. Price Sharing Formula (PSF) and formation of Primary Producer Societies (PPSs) were major reforms acclaimed to be efficient. This paper focuses on to what extent these two major reforms benefitted the STGs by insulating them from price shock and suggesting policy and strategic directions. Time series data, obtained from various published sources and primary data, collected from performing and non-performing Primary Producer Societies (PPSs) were used to analyze the impact of the two major reforms. There were both temporal and spatial variations in prices paid to STGs as per the PSF by the Bought Leaf Factories (BLFs). Members of the performing PPSs could be able to insulate them from price shock by adopting various coping mechanisms, while the members in case of non-performing PPSs were affected by the price shocks. Strict enforcement of the PSF formula by monitoring those BLFs, which have continuously been paying the prices less than PSF to the farmers and upgrading those BLFs are critically important. Since the role of PPSs is critical in executing the quality in tea leaf plucking and enforcing strictly the various pricing structure for various grades of green leaves, creating, and intensifying the awareness campaigns and membership drives in the rural areas are vital. Monitoring of the PPSs to strictly follow the bye-laws of society act, extension of subsidies like transport, collection sheds and pruning machines to weaker PPSs by the Tea Board of India (TBI) are very crucial. Strict regulation and inspection of the tea factories by Tea Board of India (TBI) are obligatory to ensure minimum monthly guaranteed prices to be paid to the growers every month. Providing trainings to STGs to handcraft the tea plucked from their own tea garden which makes this a cottage industry and thereby making them small entrepreneurs.

Key word: Tea Marketing Control Order (TMCO), Small Tea Growers (STGs), Price Sharing Formula (PSF), Primary Producer Societies (PPSs)

INTRODUCTION

The small tea farming sector at present contributes around 65% to the total global tea production and Indian Small Tea Growers (STGs) contribute to 36% of national production during 2014 (www.cec-india.org) and the share of small growers in India’s tea total production has now touched 52% during 2022. (www.bizzbuzz.news). Even though the emergence of small tea growers in the country has changed the tea industry considerably, small tea growers are facing several challenges related to profitability, availability of finance, sustaining production, processing, and marketing of tea leaves. The price formation for tea is now a sensitive issue in India. Growers complain that the tea manufacturing factories systematically beat down prices. A question that is being asked, how is it that the price paid to growers has been sliding incessantly, while the price that consumers pay for tea has not declined at all? Increasing cost of production of tea in small tea growing sector coupled with fall in productivity putting downward pressure on profitability and income as the market prices for tea have been falling continuously.

After the enactment of the Tea Act of 1953, several amendments were done within the Act to regulate the tea industry and benefit the Small Tea Growers (STGs) since the tea industry and STGs have been affected by the prolonged crisis of price shock. Among the major reforms brought out through several amendments in the Tea Marketing Control (TMCO) 2003, providing a guaranteed price to STGs by adopting the Price Sharing Formula (PSF), which was introduced by the Tea Board of India during 2004 based on the Sri Lankan model was critically acclaimed. Further, necessary amendments were also made in the TMCO 2003 that the farmers are encouraged to conglomerate to form groups with at least 30 members in each to avail various assistance/subsidies from the Tea Board of India and become competitive both in the domestic and international markets by producing quality leaves through adoption of various coping strategies. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India (GoI), by a notification has allowed the associations of small tea growers or a producer company which sources all the required tea leaf from its own plantation for manufacture of tea and having capacity to produce not more than 500 kilograms (kg) of tea per day. More than 130 groups have been formed in the last one-and-a-half years and many of them were registered as Primary Producer’s Societies (PPSs) under Indian Society Act.

THE FOCUS

This paper focuses on the above said two major reforms of tea marketing and their impact on STGs in terms of insulating them from price shock. More specifically to review the various reforms brought out over the period; assess the price shock; and to what extent these two major reforms helped STGs to insulate them from price shock. Based on the outcome we have suggested necessary policies and strategies required to make these reforms become much more effective in bringing out the desired results. Time series data on prices, area, production and consumption were sourced from Tea Board of India (TBI) and other published sources. Due to predominance of STGs in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, South India, price as per the PSF to be paid and price paid to the growers were used specific to Nilgiris district (Selvaraj, 2018) including the monthly minimum guaranteed prices. Primary data, collected from 20 effectively performing and 20 non-performing PPSs specific Nilgiris (Selvaraj, et.al; 2022) were used to assess the reform on formation of PPSs.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE MARKETING REFORMS IN INDIA: THE GIST

The Government of India enacted the Tea Waste (control) Order 1959 and Tea Warehouse (Licensing) Order 1989 followed by Tea Marketing Control Order 2003 and amendments were made in Delegation of power under TMCO, 2003. Tea (Distribution & Export) Control Order 2005, Tea (Marketing) Control (Amendment) Order, 2015, Amendment Order, 2016, Tea (Marketing) Control (Amendment) Order, 2018,Waste (Control) Amendment Order, 2018, Tea Warehouses (Licensing) Amendment Order, 2018, Tea Warehouses (Licensing) Amendment Order, 2019, Tea Waste (Control) Amendment Order, 2019, Tea Marketing Control Order (TMCO) (2nd Amendment) 2021 were implemented by notifying various amendments.

Tea (Marketing) Control Order 2003: Every registered manufacturer, sell such percentage as may be specified from time to time by the Registering Authority, of tea manufactured by him in a calendar year or such period as may be specified in the direction, through public tea auctions in India. Every registered manufacturer who sells tea outside the public tea auction shall do so only to registered buyers or through his own retail outlets or branches directly to consumers or by way of direct exports. Adherence to the Standard of Tea by manufacturers/buyers. No manufacturer shall manufacture tea which does not conform to the specification as laid down under the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act 1954 as amended from time to time or any other rules for the time being in force. Every registered manufacturer engages in purchase of green tea leaves shall pay to the supplier of green leaves a reasonable price according to the price sharing. For the said purpose, the reasonable price for tea leaves that is payable to the supplier of green leaf according to the price sharing formula shall be determined considering the sale proceeds received by the registered manufacturer.

Tea (Marketing) Control (Second Amendment) Order, 2015: “Bought leaf tea factory” means a tea factory which sources not less than 51% of its tea leaf requirement from other tea growers during any calendar year for the purpose of manufacture of tea. Every registered tea manufacturer shall, on and from the date of commencement of this notification, sell not less than 50% of the total tea manufactured in a calendar year through public tea auctions in India.

Tea (Marketing) Control (Amendment) Order, 2017: “Mini tea factory” means a tea factory owned by a small tea grower, an association of small tea growers or a Producer Company and which sources all the required tea leaves from its own plantation for the purpose of manufacture of tea and having the capacity to produce not more than 500 kg of processed tea per day.

Tea Marketing Control Order (TMCO) (2nd Amendment) 2021: To monitor the average green leaf price payable to the small tea growers for each month based on the average auction price of tea manufactured by the Bought leaf factories of such district for the same month by applying the price sharing formula.

SMALL TEA GROWERS: THE INDIAN PERSPECTIVES

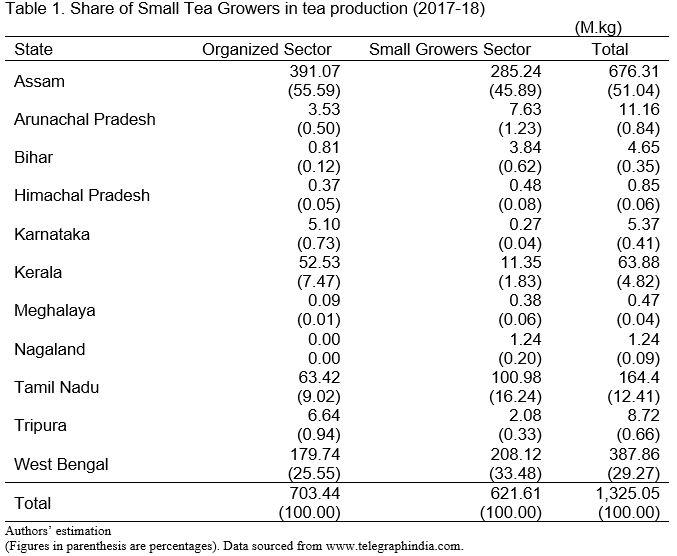

If a person cultivates tea in an area of up to 25 acres (10.12 ha) is considered as an STG by TBI to extend various services to STGs. However, most of the STGs own less than 2 acres (0.81 ha) of land, which are highly scattered. The remoteness and scattered holdings force them to market their green leaves through various exploitative trade channels. Even though the emergence of small tea growers in the country has changed the tea industry considerably, small tea growers are facing several challenges related to profitability, availability of finance, sustaining production, processing, and marketing of tea leaves. India has altogether around 0.25 million small tea growers and according to tea board data, 1,278.07 million kg tea was produced in India from January to November 2022, to which the small tea sector contributed 660.73 million kg, around 52% of the total (www.telegraphindia.com; Elosie et,al, 2018). The share of STGs in South India comprising Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka together accounts for 18.11% of the total tea produced from the STGs in India. Among the South Indian States, STGs are predominant in Tamil Nadu State contributing more than 16% of Indian tea production (Table 1). The STGs in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu state contribute to 14% of the total South Indian tea production while their percentage of contribution to all India tea production is around 3%. Nilgiris tea which constitutes about 23% of India's total tea production is characterized by small holdings (www.teaboard.org).

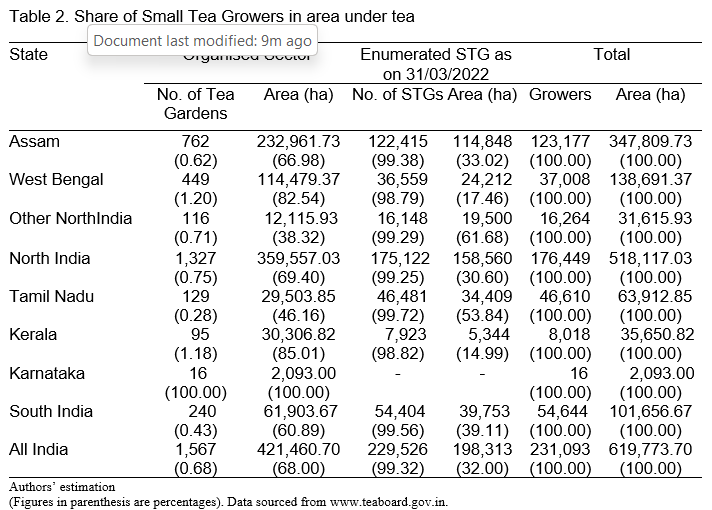

As per the 1980 techno economic survey of Nilgiris Tea Industry of Tea Board (https://teaboard.gov.in), a little over 6,000 small tea gardens in the Nilgiris were registered with the Tea Board covering an area of over 7,000 ha against an all-India figure of 12,000 with an area of nearly 13,000 ha. The area from the small tea sector constitutes 70.48% in 2004 and that of production is 66.02%. Tea is grown in nearly 70% of cultivated area covering an area of 55,420 ha during 2013-14, while it was 55,504 ha during 2012-13. Number of STG estates has increased from 6,375 during 1971 to 55,601 during 1999 and presently the figures say it is close to 50,000. Consequently, area under STGs has increased from 7,237 ha during 1971 to 36,774 ha during 1999 and presently it is close to 40,000 ha (www.teaboard.org). According to Tea World -an initiative of KKHSOU, in Tamil Nadu almost 62% production comes from the small grower’s sector. Presently the share of area under STGs is 32% at all India level and in Tamil Nadu it is 54%. There are 46,481 STGs in Tamil Nadu as per the enumeration dated 31/03/2022 (Table 2). At present there are about 61,980 number of small tea growers and more than 98 % of the plantations are in Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu State (www.teaboard.org) emphasizing the need for empowering the STGs in Tamil Nadu particularly in the Nilgiris district, where the whole economy is depending on tea cultivation.

GLOBAL COMPETITIVENESS AND PRICE SHOCK

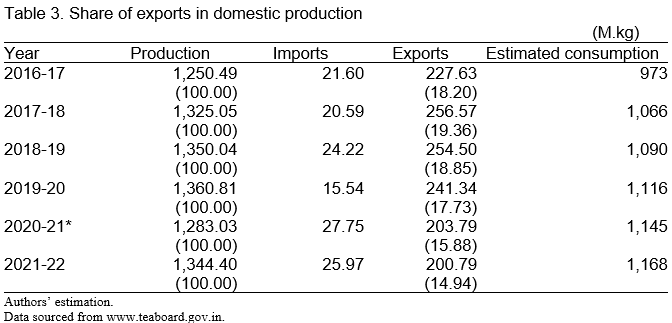

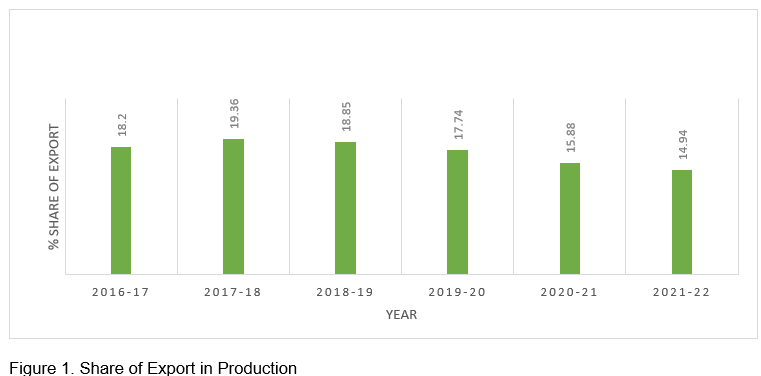

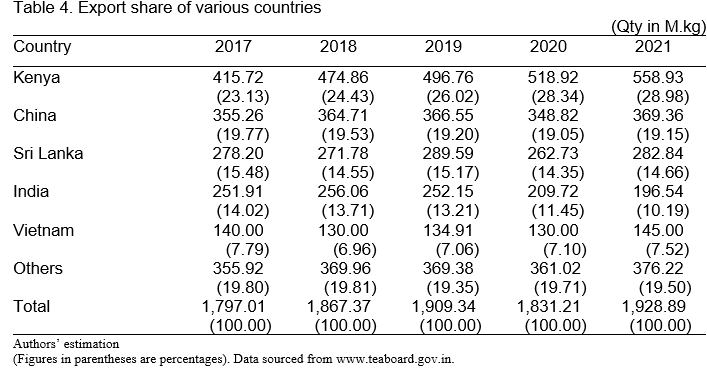

India is globally the second largest producer of tea, after China and the major consumer of tea. Domestic consumption has increased consistently throughout the years and during the fiscal 2020-21, India consumed 89.24% of its tea production (1,145 million kg) showing an increase of 2.60% over the previous period (Table 3 and Figure 1). The Indian tea market is expected to grow annually at the rate of 4.2% between 2021 and 2026. Of the total tea production in India, about 15 to 20% is exported to various countries. With the rise in the economic growth of the country, along with the growing middle-class population, the tea market in India is growing, owing to the increasing preference for premium brands. According to the United Planters Association of Southern India (www.upasi.org) report, 56% of the tea produced in Nigiris is consumed domestically and the surplus is exported to over 100 countries. Cutting, Turning and Crushing (CTC) method of tea manufacturing is popular and about 88% of the tea is produced using CTC method and 10% is produced using orthodox method while the rest is green tea production. The traditional markets of Indian tea like USSR and UK have drastically reduced their tea imports of tea from India, and the competition between producing countries, presently 36 countries of the world produce tea and many of them are big producers, are the major causes of the falling price of Indian tea (Table 4).

India was earlier exporting about 50 million kg of tea to Russia and 60% of it was from the south. In the last few years, India’s exports have declined to 40 million kg. There is scope to bring it back to 50 million kg. Russia imports almost 160 million kg of tea annually, with Sri Lanka, India and Kenya being the three major exporters to that country and Kenya’s exports increasing (The Hindu, 23/1/16). Literatures claim that the defects in auction system, poor price realization, defective market structure and increase in cost of production also attributed factors for the crisis (John, 2020). A paradoxical situation is that large tea companies are benefiting from fall in auction prices and rise in retail prices for tea. This widening gap between consumers and auction prices is cutting into the margins realized by the tea producers but is not being passed on to the consumers in the form of lowered tea prices. Average price for medium quality tea sold in Indian market increased from US$ 1.04 – 1.10 per kg in 1999 to US$ 1.46 – 1.71 per kg in 2005 and it continues to rise (The New Indian Express, 2/15/2016).

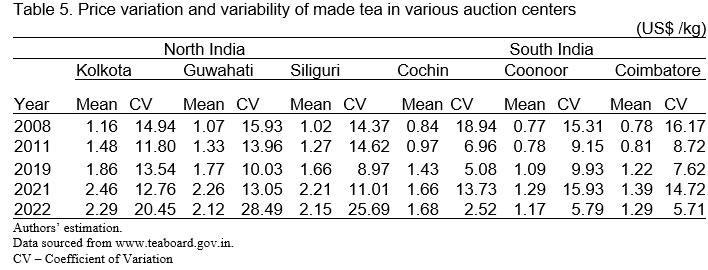

Dramatic fall in prices of green leaf tea with high variability is one of the most significant causes of the crisis in the tea industry due to a decline in demand for Indian tea in the global market, which was estimated at 1.5-2.0% per annum (Tea Board Annual Reports, 2014-15). The figures set out in the Table 5 prove that price realized by the south India tea continue to be steadily low compared to North India Tea. The price realized was US$ 1.16/kg of processed tea during 2008 that increased progressively to US$ 2.29/kg during 2022 witnessing almost 7% growth annually in the case of North India processed tea. However, the price of south Indian processed tea was US$ 0.77/ kg in the year 2008 and it increased to US$ 1.17/kg in the year 2022 witnessing an annual growth of 3.5% in nominal terms. Further, the estimated variability coefficients also indicate that south Indian made tea prices show higher volatility (both intra and inter years) with nominal increase in prices compared to North Indian tea. Many studies have proven the fact that the decline in the export demand for south India tea and quality are the major factors that are severely affecting south India’s tea industry.

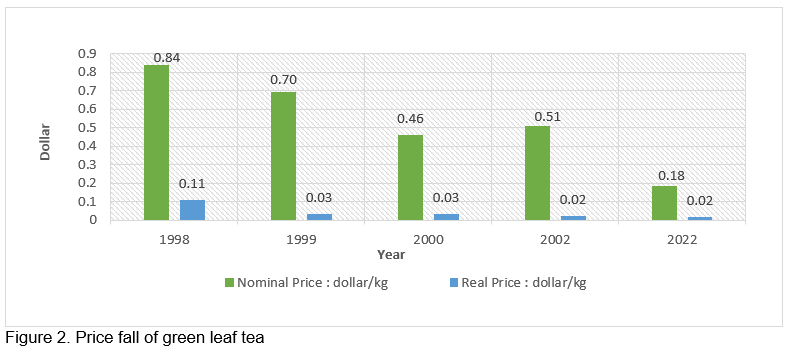

The price received by Nilgiris tea growers per kg of tea in the year 1998 was US$ 0.84 which drastically reduced to US$ 0.70 and US$ 0.46/kg in the year 1999 and 2000 respectively. In the year 2002, the price received by the Nilgiris tea growers was US$ 0.51. The green leaf tea prices for the last decade hovering around US$ 0.10 to 0.18/ kg, which is less than the cost of production (The New Indian Express, 2/15/16; DT NEXT dated 10/26/22; the Hindu Business Line, 2016). Price fall was drastic in real terms as evident from Figure 2 (Selvaraj, 2022). The small tea cultivators have been asking for ‘minimum support price’ for green leaf tea for more than a decade. According to a survey done by Indian Institute of Plantation Management (IIPM) Bangalore, the minimum cost of production of green leaf tea would be around US$ 0.21 and 50% of that would be added as social cost for the farmer, which means the minimum support price should be between US$ 0.30 and US$ 0.33 (www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/10/9/15). Many are of the opinion that unbridled growth of small tea growers has resulted in oversupply of teas which at times are not of good quality, thereby impacting the overall market (Vijayabaskar and Viswanathan, 2019).

Fall in prices both domestically and internationally and increase in cost of production are the most significant causes for poor maintenance of tea gardens; literature says more than 30% of the tea grown areas being above the economic threshold age limit (Pallavi and Liby, 2012, Ted Board, 1980) leading to the decline in productivity affecting the farmers’ livelihood in the district which contributes to more than 30% of total area and production in South India. Since small tea sector constitutes more than 50% with production share of more than 60%, the price shock has long term impact on their livelihood system including migration and the economy as well. However, estimated technical efficiencies of the studies found that STGs are technically efficient and further scope exits improve the productivity (Karabi and Dbarshi, 2020).

MAJOR TEA MARKETING REFORMS AND THEIR IMPACT

Price sharing formula

One such measure to provide a guaranteed price to STG is the Price Sharing Formula (PSF), which was introduced by the Tea Board of India during 2004 based on the Sri Lankan model. The price-sharing formula envisaged that the sale proceeds were to be shared between the smallholder and the manufacturer-processor in the ratio of 60:40. It was argued that the present formula, modeled after the one at Sri Lanka, incorporated in Tea Market Control Order (TMCO), has not yielded the desired results due the lack of transparency. One reason why the Sri Lankan model did not succeed here is that unlike India, in Sri Lanka more than 95% of the tea produced is sold through auction. Hence, Tea Board has decided to take a fresh look at the prevailing price sharing formula which is supposed to ensure a remunerative price to small tea growers as well as a fair return to bought leaf factories. Initially, the price sharing formula under TMCO was 60:40 but later the Tea Board had unilaterally changed it to 65:35.

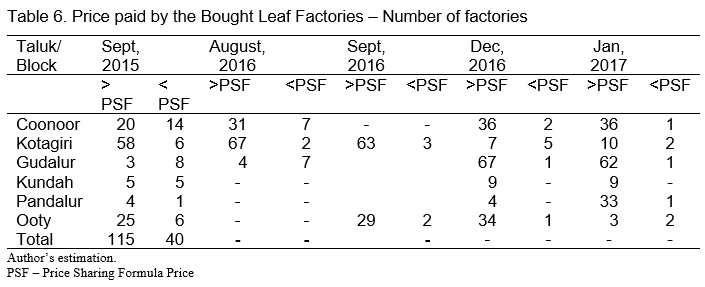

It was found that during the month of September 2015, out of 155 Bought Leaf Factories (BLF), 115 BLFs paid the price to the growers more than the Price Sharing Formula Price (PSF) and 40 BLFs paid less than the PSF price, consequently it had impacted the small tea grower’s income. Among the blocks in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, number of BLFs paid less than PSF was higher in Coonoor and Gudalur. In Coonoor block, out of 34 BLFs, 20 paid more than PSF and 14 less than PSF. In Gudalur, out of 11, 3 BLFs paid more than PSF and 8 BLFs paid less than PSF. Out of 64 BLF in Kotagiri block, 58 BLF paid more than PSF, while in Ooty block out of 31 BLFs, 25 paid more than PSF (Table 6). Since, PSF formula has not yielded the desired results due the lack of transparency, PSF Tea Board has constituted a committee to fix monthly minimum average price for green leaves based on the scientific formula since last five years. According to Section 30 of Tea Marketing Control Order 2003, the district average price for green leaf for every month is being fixed based on the consolidated auction sale average of CTC teas from BLFs during the previous month and all BLFs in the district are instructed to adhere to this average green leaf price while buying green leaf from the farmers. All field officials of Tea Board shall ensure that no bought leaf factory in their jurisdiction pays lower than this price. However, the minimum monthly average prices are hovering around US$0.15 -0.22/kg of green leaves, while the STGs seek US$ 0.37 /kg as minimum price of green leaves due to increase in cost of production which was estimated around US$0.27 to 0.30/ kg. The BLFs are requesting TBI that fixation of district average green leaf price should be at the end of each month due to sale postponing and sale cancellation by TBI.

Primary producer societies

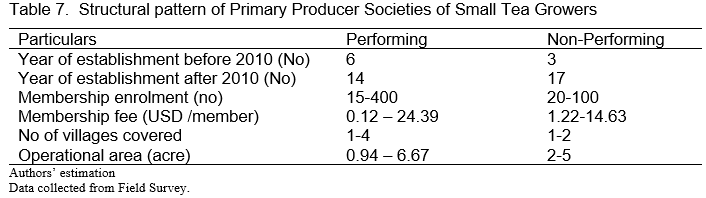

Field survey and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) were conducted using structured questionnaire. The criteria for selection of PPSs as performing and non-performing are based on their current functioning. The PPSs which were functioning regularly were taken as performing PPSs and the PPSs which had stopped their operations and are not functioning were taken as non-performing PPSs. A total of 40 PPSs (20 each i.e., functioning and non-functioning presently regardless of date of formation) were surveyed personally and data were elicited. About 52% of the PPSs were formed before 10 years, while 48% of the PPSs were established within 10 years. Subsequently every year two or three societies were established till current year. We observed that some non-performing societies became defunct within a short spell of time (after two years of establishment) and few of them became defunct after six years of establishment. We found that the period of establishment has no significant effect on functioning and there is no strong correlation between the period of establishment and performance of the societies. The observation is that more than 30% of the performance societies were formed prior to 2010 and remaining 70% of the societies were formed after 2010. On the contrary we found that there were 17 non-performing societies which were established after 2010 and they became defunction within a short period of time due to various reasons (Table 7).

All the non- performing societies were of the opinion that lack of cooperation among the members of the society is one of the major reasons for the failure. Mahindapala (2020) found that individual factors and group dynamics have a bearing on the performance of the Tea Smallholding Development Societies (TSDS). Since most of the unsuccessful societies are dependent on exploitative trade channels to sell their produce, unfair price of green leaves adds to their vulnerability and affects their success and access to other services. Many of the non-performing societies reported that improper payment by the bought leaf factories is one of the causes for dysfunction (90%) and such improper payment led to disinterest among the members to continue as member of the society. Consequently, many members supplied green leaves either directly to the factories of their choice or to the tea agents depending upon the quantity and location of the farm. Other reasons cited by most of the members of societies for the organizational failures are improper maintenance of accounts, not conducting meetings regularly and lack of funds and not availing the subsidies from TBI. Since the meetings were not conducted on a regular basis, members have low levels of technical knowledge and business skills and they lack awareness about government support and face shortage of funds.

The prolonged crisis in the tea sector led to disinterest among the members. Even though in some societies the member numbers swell, due to remoteness and scattered nature of existence, they lack organization and bargaining capacity. Similar in the case of the Panbari Small Tea Growers Society at West Bengal, in which members enrollment decreased by 12% after a year of establishment and production declined at the rate of 6% every year. However, production of orthodox tea with own brand for export helped to succeed (Saha, 2020; Abdul Hannan, 2019). Studies by Katuwal (2020) and Karki., et.al. (2011) also demonstrated that membership enrollment, credit and targeting specialty tea markets are vital for success of the societies.

We found that the cost of production is increasing consistently both in the nominal and real terms widening the gap between the product price and the cost since the product price is declining as a result the parity is lost. At the prevailing green leaf prices, famers are incurring loss and they are not able to meet even the variable cost. Among various costs, labor cost accounts for around 85% of the unit cost of production and of the total labor cost, cost of plucking accounts for 55 to 75%, which is the major factor bringing down the profit margin. Further hikes in every other essential input including fertilizers, herbicides and pest control chemicals are reducing earnings and holding back investments in quality at a time when only good quality teas are competitive. The hike in cost of labor in tea manufacturing industries has also had a negative impact on STGs as it was estimated that an additional US$ 0.05/ kg for manufactured tea in NE Region of India and US$ 0.40/kg in South India had to be met in the last two decades resulting in downward impact on prices of green tea leaves (Pallavi and Liby, 2012).

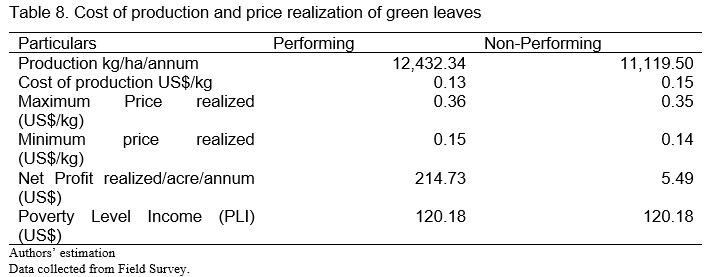

The estimated green leaves production per year was 12,432 kg/ha in the case of performing societies, while it was 11,120 kg/ha in the case of non-performing societies (Table 8). Members of performing societies obtained 12% higher yield when compared to their counterparts mainly due to strict quality enforcement particularly the number of plucking per month and method of plucking. For example, the Eswarar Society is one of the prominent and awarded societies in the Nilgiris district, which is enforcing various quality parameters among the farmers for quality tea production. The members are supplied with soil health card to assess the status of the soil for optimum allocation of fertilizer inputs.

Since tea cultivation is one of the most labor-intensive activities, particularly plucking, cost-cutting measures would significantly reduce the cost of production and mechanization is one of the effective alternatives that can reduce costs. Functioning of Backward Bending Supply Curve (as real wages increase beyond a certain level, people will substitute leisure for paid worktime and so higher wages lead to a decrease in the labor supply) is compelling the STGs to resort to mechanization of their small tea gardens. Several initiatives on mechanization by Tea Board have been undertaken to reduce the cost of labor. Field survey estimates based on the Front-Line Demonstration by KVK- UPSAI (Ramamoorthy and Shanmugam, 2013) show that average harvesting cost by mechanical harvester was lower and two workers operating a mechanical harvester for a day can bring in the equivalent of leaf of 15 workers hand-plucking tea. Mechanically harvested tea bested hand plucked tea and tea obtained by shear-harvesting from a continuously sheared field over a prolonged period was found to be superior (www.worldteanews.com). On an average, members of performing society incurred US$ 0.13/ kg of green leave production, while it was US$ 0.15/kg in the case non-performing societies. The difference in cost of production between the two categories of societies is due to mechanization of harvesting in the case of performing societies. One of the reasons for better performance of the PPSs is sharing of harvesting machines among the members on custom hiring basis with nominal cost as a result the members of the performing societies realized higher productivity with lesser cost. Members of the performing societies realized a maximum price US$ 0.36/ kg of green leaves and minimum price of US$ 0.15/kg. On the other hand, the members of the non- performing societies received a maximum price US$ 0.35/kg and minimum price US$ 0.13/kg.

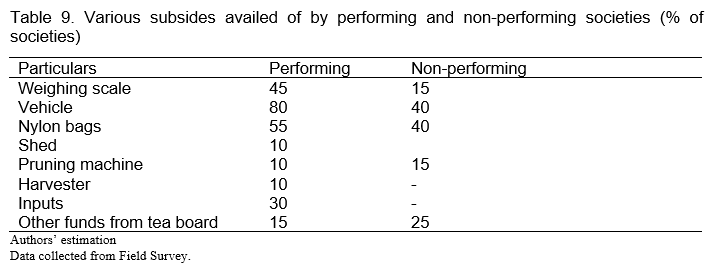

Collection of green leaves from each farm adds to cost of production and cutting down the margins for the members due to high transportation cost as STGs are scattered. Availing subsidy from tea board for purchase of vehicle is critical for their success as cost of transportation of green leaves from the collection center to factories sharply reduces marketing cost thereby the society can provide a better price for the members. Through our survey we found that 80% of the performing societies have their own vehicle for transportation of green leaves by availing 50% subsidy from tea board. On the contrary only 40% of the non-performing societies availed subsidy for purchase of own vehicle (Table 9). Similarly, performing societies benefitted more from various subsidies provided by tea board compared to non-performing societies.

The demand for the packaged varieties of the beverage in urban as well as rural areas is rising owing to the lesser chances of adulteration, superior quality, and convenient storage. People are willing to experiment with more tea blends, further providing an impetus for the growth of segments such as herbal, fruit, and other specialty varieties. The green tea segment is predicted to have a robust growth due to its vast consumption among health-conscious people and the urban population. Tea Board of India is giving a big push to organic tea production by providing 25% more subsidy than the normal subsidy of 30% and also 50% of the cost of certification will be paid as subsidy. Further, the Government of India under Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) implemented the organic tea cultivation program in 100 acres of tea gardens comprising of 100 Small Tea Growers (STG) through Department of Horticulture. Most of the times the price of tea leaves paid to the small tea growers is not sustainable for their livelihood, hence the concept of hand-crafted tea by the small producers need to be promoted and TBI have already been taken initiatives. Providing trainings to members of both the categories of societies so that the members are trained to handcraft the tea plucked from their own tea garden which makes this a cottage industry and thereby making them small entrepreneurs. These initiatives are helping the member-farmers of the societies to practice organic tea cultivation in order to improve income by realizing premium price. Improvement in the maintenance of quality standard in tea plucking, production of specialized tea by the small tea growers etc. would lead to a better price fetching mechanism and also better product demand. Thus, strategic approaches such as value addition, product diversification, integration of services through cohesiveness and collective practices through member’s cooperation are vital for effective functioning of the societies to insulate from price risks.

FUTURE POLICY/ STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS

The green leaf prices for the last one-decade hovering around US$ 0.10 to 0.18/kg, which is less than the cost of production. Even the district average price, fixed to ensure remunerative prices for the famers are always lower the cost of production. The prices realized for South and North Indian tea show that aberration in price of South India tea was higher compared to North Indian tea due to various factors particularly due to quality. Increasing cost of production of tea in STG tea sector coupled with fall in productivity putting downward pressure on profitability and income as the market prices for tea have been falling. Among the various reforms, prices paid to STGs as per the PSF show wider variations among the BLFs in various time periods. Strict enforcement of the policy and identification of those BLFs, which has been continuously paying the prices less than PSF and upgrading/modernization of those factories is critically important in order to improve their production capacity and efficiency in made tea production for better price realization so that the higher price realized is transmitted to the STGs. Monitoring of the societies to strictly to follow the bye-laws of society act, extension of subsidies like transport, collection sheds, pruning machines and others under various categories to weaker societies are very critical. There is a need for regulation and inspection of the tea factories by Tea Board to ensure better price realization and successful/effective functioning of the societies. The role of Primary Producers Societies (PPS) is critical in executing the quality in tea plucking and enforcing strictly the various pricing structure for various grades of green leaves in order to encourage the members to adopt the recommended packages of practices for production of quality green leaves.

To overcome the crisis since 1999, various measures have been implemented to mitigate the crisis to sustain tea production and bring in the decent livelihood to small holders. Among the several measures, production of organic tea is practiced for better price realization. These initiatives are helping the farmers to practice organic tea cultivation in order to improve income by realizing premium price. Though organic tea production is gaining momentum among the small tea growers, yield reduction after conversion is a major threat. Despite the fact that there is a yield reduction, our sample of organic tea growers were benefitted from higher remunerative price for their green tea leaves due to adoption of quality tea plucking practices with opinion that certification would help them to realize better prices due to market acceptance. As long as Small Tea Growers (STGs) could be able to realize premium market prices they are ready for conversion. It is also found that there is a long-term beneficial impact both in-terms of soil and crop productivity as evident from the soil sample analysis we did. Export price for organic tea is twice than that of normal tea but export share was minimal emphasizing the need for higher level of export for which formal certification is crucial since the organic tea exporters cannot source tea from uncertified STG organic farms. The awareness for certification is lacking though trainings and demonstration are being carried out by the various agencies. In this context of crisis of continuous price fall and losing the export markets due to competitiveness, organic production is one of the alternatives among the STGs to have decent livelihood. The role of Primary Producers Societies (PPS) is critical in enforcing the quality for organic tea production and marketing. Production of specialty tea like white tea and direct market linkages with export market for packed tea with a trademark were the key strategies adopted to insulate the price shock and that we observed only among few performing societies. The successful societies with higher coverage can resort to their own value addition by establishing micro and mini tea factories and creating their own trademark and marketing. The concept of hand-crafted tea by the small producers have already been promoted by TBI. Providing trainings to members of both the categories of societies so that the members are trained to handcraft the tea plucked from their own tea garden which makes this a cottage industry and thereby making them small entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Abdul Hannan (2019. Farm Size and Trade Relations of Small Tea Growers (STGs) in Assam and North Bengal. Social Change and Development. Vol. XVI No.2. pp 78 -99. Small Tea Growers in other states of India. teaworld.kkhsou.in/page-details.php

Annual Reports, 2014-15. www.teaboard.org

Eloise M. Biggs, Niladri Gupta, Sukanya D. Saikia, John M.A. Duncan (2018). Tea production characteristics of tea growers (plantations and smallholdings) and livelihood dimensions of tea workers in Assam, India. Data in Brief 17. 1379–1387 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dib

John Mano Raj, S (2020). Role of Market Intermediaries and Marketing Practices of Small Tea Growers in Assam. Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology. Volume XII, Issue III. Pp 209 to 217.

Karabi Das and Debarshi Das (2020). Technical Efficiency in Small Tea Gardens of Assam Review of Development and Change. 25(1). Pp: 112–130.DOI: 10.1177/0972266120916318 journals.sagepub.com/home/rdc

Karki A, L., Schleenbecker B, R., Hamm, U. (2011). Factors influencing a conversion to organic farming in Nepalese tea farms. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 112(2), 113–123.

Katuwal Narendra l (2020). Factors influencing small farmers’ participation in the extension of tea farming: a case of ilam, Nepal. EPRA International Journal of Agriculture and Rural Economic Research (ARER) - Peer-Reviewed Journal. Volume: 8 Issue: DOI: 10.36713/epra0813

Mahindapala, K.G.J.P (2020), Are Tea Smallholders’ Farmer Organisations in Sri Lanka Focused Towards Sectoral Issues? A Review on Present Status and Way Forward. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Review (JSSHR). Vol. 5, No. 3 (129-145) DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/jsshr.v5i3.66

Modalities and Scheme Guidelines of Tea Development and Promotion Scheme, 2021-2026, www.teaboard.gov.in

Pallavi, M., Liby, J. T. (2012). Comparative Analysis of Existing Models of Small Tea Growers in Tea Value Chain in the Nilgiris. NRPPD Discussion Paper. http://www.cds.edu/wp- content/uploads/2012/11/NRPPD20.pdf

Ramamoorthy, G., Shanmugam, R. 2013. Intervention and Impact of Machine Harvesting in tea among small farmers of Nilgiris District. www.upasikvk.org/download/intervention/harvesting.pdf

Saha Debdulal (2020). Producer collectives through self-help: sustainability of small tea growers in India International Review of Applied Economics. https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cira2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2020.1773646.

Selvaraj, K. N. and R. Ganesh (2017). Transformation to Organic Production among the Small Tea Holders for Sustainability – Myth or Reality? The 9th ASAE International Conference: Transformation in agricultural and food economy in Asia.11-13 January 2017 Bangkok, Thailand. Pp: 106 to 129.

Selvaraj, K.N. (2018). Price Sharing Formula and Price Realization by the Small Tea Growers in the Nilgiris District. Research Report (CARDS/OTY/AEC/2016/001). Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore

Selvaraj, K.N., K.R. Karunakaran, R. Parimalarangan and K.Divya (2022). Performance Evaluation of Primary Producer Societies of Small Tea Growers in the Nilgiris District. Research Report (STGS/ CARDS/ CBE /AEC/2012/RO26). Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore

Selvaraj K.N (2022). Invited Speaker Speech on Conglomeration of Farmers - A Development Initiatives for Securing Livelihood in the Case of Small Tea Growers in India Abstracts of International Conference “Innovation for Resilience Agriculture” October 19-21, 2022, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. PP. 28-30 www: https://agri.cmu.ac.th

Tea growers anguished at plummeting prices 10/26/22, DT NEXT

The Hindu – Business Line. (2016) Indian tea price has not increased in real terms. Retrieved from http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/indian-tea-pri... terms/article9115697.ece

The Hindu (2015) Scope to raise tea exports to Russia. Retrieved from http://www.thehindu.com/business/Industry/scope-to-raise-tea-exports-to Russia/article7671145.ece

The New Indian Express, 2/15/2016/Falling Green Leaves Prices

Vijayabaskar, M and P.K. Viswanathan (2019). Emerging Vulnerabilities in India’s Tea Plantation Economy: A Critical Engagement with Policy Response MIDS Working Paper No. 233.

The telegraph. (2023) e-paper news. Retrieved from the telegraph online e-paper news website: https://www.telegraphindia.com/content/India’s border lands/vibrant village programme/border village of kibithoo in Arunachal Pradesh/Valour of Army & ITBP ensures no/one can encroach even inch of India’s land.

The center for education and communication. (2023). 2016 Sustainable livelihoods for small tea growers report. Retrieved from the center for education and communication website: www. cec-india.org/small-tea-growers.php-2016-sustainability-report-the center for education and communication website page.

The Hindu. (2021) article 37022667 welfare responsibilities making organized sector’s output costlier page news. Retrieved from the Hindu online article news website page:www.thehindu.com/news/national/small-growers-edging-out-big-players-tea- body/article37022667.ece.

The teaworld.kkhsou.in. (2017-18) growth of small-scale tea cultivation content page. Retrieved from tea world website: the www. teaworld.kkhsou.in/Small Tea Growers in other states of India.

Tea Marketing Reforms in India – Challenges and Opportunities for Small Tea Growers (STGs) to Insulate from Price Shock

ABSTRACT

Several reforms were brought in through several amendments in the Tea Marketing Control 2003 to safeguard the Small Tea Growers (STGs) from the prolonged price crisis. The green leaf tea prices for the last decade hovering around US$ 0.10 to 0.18/ kg (INR 82/US$), which is far below the cost of production. Price Sharing Formula (PSF) and formation of Primary Producer Societies (PPSs) were major reforms acclaimed to be efficient. This paper focuses on to what extent these two major reforms benefitted the STGs by insulating them from price shock and suggesting policy and strategic directions. Time series data, obtained from various published sources and primary data, collected from performing and non-performing Primary Producer Societies (PPSs) were used to analyze the impact of the two major reforms. There were both temporal and spatial variations in prices paid to STGs as per the PSF by the Bought Leaf Factories (BLFs). Members of the performing PPSs could be able to insulate them from price shock by adopting various coping mechanisms, while the members in case of non-performing PPSs were affected by the price shocks. Strict enforcement of the PSF formula by monitoring those BLFs, which have continuously been paying the prices less than PSF to the farmers and upgrading those BLFs are critically important. Since the role of PPSs is critical in executing the quality in tea leaf plucking and enforcing strictly the various pricing structure for various grades of green leaves, creating, and intensifying the awareness campaigns and membership drives in the rural areas are vital. Monitoring of the PPSs to strictly follow the bye-laws of society act, extension of subsidies like transport, collection sheds and pruning machines to weaker PPSs by the Tea Board of India (TBI) are very crucial. Strict regulation and inspection of the tea factories by Tea Board of India (TBI) are obligatory to ensure minimum monthly guaranteed prices to be paid to the growers every month. Providing trainings to STGs to handcraft the tea plucked from their own tea garden which makes this a cottage industry and thereby making them small entrepreneurs.

Key word: Tea Marketing Control Order (TMCO), Small Tea Growers (STGs), Price Sharing Formula (PSF), Primary Producer Societies (PPSs)

INTRODUCTION

The small tea farming sector at present contributes around 65% to the total global tea production and Indian Small Tea Growers (STGs) contribute to 36% of national production during 2014 (www.cec-india.org) and the share of small growers in India’s tea total production has now touched 52% during 2022. (www.bizzbuzz.news). Even though the emergence of small tea growers in the country has changed the tea industry considerably, small tea growers are facing several challenges related to profitability, availability of finance, sustaining production, processing, and marketing of tea leaves. The price formation for tea is now a sensitive issue in India. Growers complain that the tea manufacturing factories systematically beat down prices. A question that is being asked, how is it that the price paid to growers has been sliding incessantly, while the price that consumers pay for tea has not declined at all? Increasing cost of production of tea in small tea growing sector coupled with fall in productivity putting downward pressure on profitability and income as the market prices for tea have been falling continuously.

After the enactment of the Tea Act of 1953, several amendments were done within the Act to regulate the tea industry and benefit the Small Tea Growers (STGs) since the tea industry and STGs have been affected by the prolonged crisis of price shock. Among the major reforms brought out through several amendments in the Tea Marketing Control (TMCO) 2003, providing a guaranteed price to STGs by adopting the Price Sharing Formula (PSF), which was introduced by the Tea Board of India during 2004 based on the Sri Lankan model was critically acclaimed. Further, necessary amendments were also made in the TMCO 2003 that the farmers are encouraged to conglomerate to form groups with at least 30 members in each to avail various assistance/subsidies from the Tea Board of India and become competitive both in the domestic and international markets by producing quality leaves through adoption of various coping strategies. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India (GoI), by a notification has allowed the associations of small tea growers or a producer company which sources all the required tea leaf from its own plantation for manufacture of tea and having capacity to produce not more than 500 kilograms (kg) of tea per day. More than 130 groups have been formed in the last one-and-a-half years and many of them were registered as Primary Producer’s Societies (PPSs) under Indian Society Act.

THE FOCUS

This paper focuses on the above said two major reforms of tea marketing and their impact on STGs in terms of insulating them from price shock. More specifically to review the various reforms brought out over the period; assess the price shock; and to what extent these two major reforms helped STGs to insulate them from price shock. Based on the outcome we have suggested necessary policies and strategies required to make these reforms become much more effective in bringing out the desired results. Time series data on prices, area, production and consumption were sourced from Tea Board of India (TBI) and other published sources. Due to predominance of STGs in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, South India, price as per the PSF to be paid and price paid to the growers were used specific to Nilgiris district (Selvaraj, 2018) including the monthly minimum guaranteed prices. Primary data, collected from 20 effectively performing and 20 non-performing PPSs specific Nilgiris (Selvaraj, et.al; 2022) were used to assess the reform on formation of PPSs.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE MARKETING REFORMS IN INDIA: THE GIST

The Government of India enacted the Tea Waste (control) Order 1959 and Tea Warehouse (Licensing) Order 1989 followed by Tea Marketing Control Order 2003 and amendments were made in Delegation of power under TMCO, 2003. Tea (Distribution & Export) Control Order 2005, Tea (Marketing) Control (Amendment) Order, 2015, Amendment Order, 2016, Tea (Marketing) Control (Amendment) Order, 2018,Waste (Control) Amendment Order, 2018, Tea Warehouses (Licensing) Amendment Order, 2018, Tea Warehouses (Licensing) Amendment Order, 2019, Tea Waste (Control) Amendment Order, 2019, Tea Marketing Control Order (TMCO) (2nd Amendment) 2021 were implemented by notifying various amendments.

Tea (Marketing) Control Order 2003: Every registered manufacturer, sell such percentage as may be specified from time to time by the Registering Authority, of tea manufactured by him in a calendar year or such period as may be specified in the direction, through public tea auctions in India. Every registered manufacturer who sells tea outside the public tea auction shall do so only to registered buyers or through his own retail outlets or branches directly to consumers or by way of direct exports. Adherence to the Standard of Tea by manufacturers/buyers. No manufacturer shall manufacture tea which does not conform to the specification as laid down under the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act 1954 as amended from time to time or any other rules for the time being in force. Every registered manufacturer engages in purchase of green tea leaves shall pay to the supplier of green leaves a reasonable price according to the price sharing. For the said purpose, the reasonable price for tea leaves that is payable to the supplier of green leaf according to the price sharing formula shall be determined considering the sale proceeds received by the registered manufacturer.

Tea (Marketing) Control (Second Amendment) Order, 2015: “Bought leaf tea factory” means a tea factory which sources not less than 51% of its tea leaf requirement from other tea growers during any calendar year for the purpose of manufacture of tea. Every registered tea manufacturer shall, on and from the date of commencement of this notification, sell not less than 50% of the total tea manufactured in a calendar year through public tea auctions in India.

Tea (Marketing) Control (Amendment) Order, 2017: “Mini tea factory” means a tea factory owned by a small tea grower, an association of small tea growers or a Producer Company and which sources all the required tea leaves from its own plantation for the purpose of manufacture of tea and having the capacity to produce not more than 500 kg of processed tea per day.

Tea Marketing Control Order (TMCO) (2nd Amendment) 2021: To monitor the average green leaf price payable to the small tea growers for each month based on the average auction price of tea manufactured by the Bought leaf factories of such district for the same month by applying the price sharing formula.

SMALL TEA GROWERS: THE INDIAN PERSPECTIVES

If a person cultivates tea in an area of up to 25 acres (10.12 ha) is considered as an STG by TBI to extend various services to STGs. However, most of the STGs own less than 2 acres (0.81 ha) of land, which are highly scattered. The remoteness and scattered holdings force them to market their green leaves through various exploitative trade channels. Even though the emergence of small tea growers in the country has changed the tea industry considerably, small tea growers are facing several challenges related to profitability, availability of finance, sustaining production, processing, and marketing of tea leaves. India has altogether around 0.25 million small tea growers and according to tea board data, 1,278.07 million kg tea was produced in India from January to November 2022, to which the small tea sector contributed 660.73 million kg, around 52% of the total (www.telegraphindia.com; Elosie et,al, 2018). The share of STGs in South India comprising Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka together accounts for 18.11% of the total tea produced from the STGs in India. Among the South Indian States, STGs are predominant in Tamil Nadu State contributing more than 16% of Indian tea production (Table 1). The STGs in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu state contribute to 14% of the total South Indian tea production while their percentage of contribution to all India tea production is around 3%. Nilgiris tea which constitutes about 23% of India's total tea production is characterized by small holdings (www.teaboard.org).

As per the 1980 techno economic survey of Nilgiris Tea Industry of Tea Board (https://teaboard.gov.in), a little over 6,000 small tea gardens in the Nilgiris were registered with the Tea Board covering an area of over 7,000 ha against an all-India figure of 12,000 with an area of nearly 13,000 ha. The area from the small tea sector constitutes 70.48% in 2004 and that of production is 66.02%. Tea is grown in nearly 70% of cultivated area covering an area of 55,420 ha during 2013-14, while it was 55,504 ha during 2012-13. Number of STG estates has increased from 6,375 during 1971 to 55,601 during 1999 and presently the figures say it is close to 50,000. Consequently, area under STGs has increased from 7,237 ha during 1971 to 36,774 ha during 1999 and presently it is close to 40,000 ha (www.teaboard.org). According to Tea World -an initiative of KKHSOU, in Tamil Nadu almost 62% production comes from the small grower’s sector. Presently the share of area under STGs is 32% at all India level and in Tamil Nadu it is 54%. There are 46,481 STGs in Tamil Nadu as per the enumeration dated 31/03/2022 (Table 2). At present there are about 61,980 number of small tea growers and more than 98 % of the plantations are in Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu State (www.teaboard.org) emphasizing the need for empowering the STGs in Tamil Nadu particularly in the Nilgiris district, where the whole economy is depending on tea cultivation.

GLOBAL COMPETITIVENESS AND PRICE SHOCK

India is globally the second largest producer of tea, after China and the major consumer of tea. Domestic consumption has increased consistently throughout the years and during the fiscal 2020-21, India consumed 89.24% of its tea production (1,145 million kg) showing an increase of 2.60% over the previous period (Table 3 and Figure 1). The Indian tea market is expected to grow annually at the rate of 4.2% between 2021 and 2026. Of the total tea production in India, about 15 to 20% is exported to various countries. With the rise in the economic growth of the country, along with the growing middle-class population, the tea market in India is growing, owing to the increasing preference for premium brands. According to the United Planters Association of Southern India (www.upasi.org) report, 56% of the tea produced in Nigiris is consumed domestically and the surplus is exported to over 100 countries. Cutting, Turning and Crushing (CTC) method of tea manufacturing is popular and about 88% of the tea is produced using CTC method and 10% is produced using orthodox method while the rest is green tea production. The traditional markets of Indian tea like USSR and UK have drastically reduced their tea imports of tea from India, and the competition between producing countries, presently 36 countries of the world produce tea and many of them are big producers, are the major causes of the falling price of Indian tea (Table 4).

India was earlier exporting about 50 million kg of tea to Russia and 60% of it was from the south. In the last few years, India’s exports have declined to 40 million kg. There is scope to bring it back to 50 million kg. Russia imports almost 160 million kg of tea annually, with Sri Lanka, India and Kenya being the three major exporters to that country and Kenya’s exports increasing (The Hindu, 23/1/16). Literatures claim that the defects in auction system, poor price realization, defective market structure and increase in cost of production also attributed factors for the crisis (John, 2020). A paradoxical situation is that large tea companies are benefiting from fall in auction prices and rise in retail prices for tea. This widening gap between consumers and auction prices is cutting into the margins realized by the tea producers but is not being passed on to the consumers in the form of lowered tea prices. Average price for medium quality tea sold in Indian market increased from US$ 1.04 – 1.10 per kg in 1999 to US$ 1.46 – 1.71 per kg in 2005 and it continues to rise (The New Indian Express, 2/15/2016).

Dramatic fall in prices of green leaf tea with high variability is one of the most significant causes of the crisis in the tea industry due to a decline in demand for Indian tea in the global market, which was estimated at 1.5-2.0% per annum (Tea Board Annual Reports, 2014-15). The figures set out in the Table 5 prove that price realized by the south India tea continue to be steadily low compared to North India Tea. The price realized was US$ 1.16/kg of processed tea during 2008 that increased progressively to US$ 2.29/kg during 2022 witnessing almost 7% growth annually in the case of North India processed tea. However, the price of south Indian processed tea was US$ 0.77/ kg in the year 2008 and it increased to US$ 1.17/kg in the year 2022 witnessing an annual growth of 3.5% in nominal terms. Further, the estimated variability coefficients also indicate that south Indian made tea prices show higher volatility (both intra and inter years) with nominal increase in prices compared to North Indian tea. Many studies have proven the fact that the decline in the export demand for south India tea and quality are the major factors that are severely affecting south India’s tea industry.

The price received by Nilgiris tea growers per kg of tea in the year 1998 was US$ 0.84 which drastically reduced to US$ 0.70 and US$ 0.46/kg in the year 1999 and 2000 respectively. In the year 2002, the price received by the Nilgiris tea growers was US$ 0.51. The green leaf tea prices for the last decade hovering around US$ 0.10 to 0.18/ kg, which is less than the cost of production (The New Indian Express, 2/15/16; DT NEXT dated 10/26/22; the Hindu Business Line, 2016). Price fall was drastic in real terms as evident from Figure 2 (Selvaraj, 2022). The small tea cultivators have been asking for ‘minimum support price’ for green leaf tea for more than a decade. According to a survey done by Indian Institute of Plantation Management (IIPM) Bangalore, the minimum cost of production of green leaf tea would be around US$ 0.21 and 50% of that would be added as social cost for the farmer, which means the minimum support price should be between US$ 0.30 and US$ 0.33 (www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/10/9/15). Many are of the opinion that unbridled growth of small tea growers has resulted in oversupply of teas which at times are not of good quality, thereby impacting the overall market (Vijayabaskar and Viswanathan, 2019).

Fall in prices both domestically and internationally and increase in cost of production are the most significant causes for poor maintenance of tea gardens; literature says more than 30% of the tea grown areas being above the economic threshold age limit (Pallavi and Liby, 2012, Ted Board, 1980) leading to the decline in productivity affecting the farmers’ livelihood in the district which contributes to more than 30% of total area and production in South India. Since small tea sector constitutes more than 50% with production share of more than 60%, the price shock has long term impact on their livelihood system including migration and the economy as well. However, estimated technical efficiencies of the studies found that STGs are technically efficient and further scope exits improve the productivity (Karabi and Dbarshi, 2020).

MAJOR TEA MARKETING REFORMS AND THEIR IMPACT

Price sharing formula

One such measure to provide a guaranteed price to STG is the Price Sharing Formula (PSF), which was introduced by the Tea Board of India during 2004 based on the Sri Lankan model. The price-sharing formula envisaged that the sale proceeds were to be shared between the smallholder and the manufacturer-processor in the ratio of 60:40. It was argued that the present formula, modeled after the one at Sri Lanka, incorporated in Tea Market Control Order (TMCO), has not yielded the desired results due the lack of transparency. One reason why the Sri Lankan model did not succeed here is that unlike India, in Sri Lanka more than 95% of the tea produced is sold through auction. Hence, Tea Board has decided to take a fresh look at the prevailing price sharing formula which is supposed to ensure a remunerative price to small tea growers as well as a fair return to bought leaf factories. Initially, the price sharing formula under TMCO was 60:40 but later the Tea Board had unilaterally changed it to 65:35.

It was found that during the month of September 2015, out of 155 Bought Leaf Factories (BLF), 115 BLFs paid the price to the growers more than the Price Sharing Formula Price (PSF) and 40 BLFs paid less than the PSF price, consequently it had impacted the small tea grower’s income. Among the blocks in the Nilgiris district of Tamil Nadu, number of BLFs paid less than PSF was higher in Coonoor and Gudalur. In Coonoor block, out of 34 BLFs, 20 paid more than PSF and 14 less than PSF. In Gudalur, out of 11, 3 BLFs paid more than PSF and 8 BLFs paid less than PSF. Out of 64 BLF in Kotagiri block, 58 BLF paid more than PSF, while in Ooty block out of 31 BLFs, 25 paid more than PSF (Table 6). Since, PSF formula has not yielded the desired results due the lack of transparency, PSF Tea Board has constituted a committee to fix monthly minimum average price for green leaves based on the scientific formula since last five years. According to Section 30 of Tea Marketing Control Order 2003, the district average price for green leaf for every month is being fixed based on the consolidated auction sale average of CTC teas from BLFs during the previous month and all BLFs in the district are instructed to adhere to this average green leaf price while buying green leaf from the farmers. All field officials of Tea Board shall ensure that no bought leaf factory in their jurisdiction pays lower than this price. However, the minimum monthly average prices are hovering around US$0.15 -0.22/kg of green leaves, while the STGs seek US$ 0.37 /kg as minimum price of green leaves due to increase in cost of production which was estimated around US$0.27 to 0.30/ kg. The BLFs are requesting TBI that fixation of district average green leaf price should be at the end of each month due to sale postponing and sale cancellation by TBI.

Primary producer societies

Field survey and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) were conducted using structured questionnaire. The criteria for selection of PPSs as performing and non-performing are based on their current functioning. The PPSs which were functioning regularly were taken as performing PPSs and the PPSs which had stopped their operations and are not functioning were taken as non-performing PPSs. A total of 40 PPSs (20 each i.e., functioning and non-functioning presently regardless of date of formation) were surveyed personally and data were elicited. About 52% of the PPSs were formed before 10 years, while 48% of the PPSs were established within 10 years. Subsequently every year two or three societies were established till current year. We observed that some non-performing societies became defunct within a short spell of time (after two years of establishment) and few of them became defunct after six years of establishment. We found that the period of establishment has no significant effect on functioning and there is no strong correlation between the period of establishment and performance of the societies. The observation is that more than 30% of the performance societies were formed prior to 2010 and remaining 70% of the societies were formed after 2010. On the contrary we found that there were 17 non-performing societies which were established after 2010 and they became defunction within a short period of time due to various reasons (Table 7).

All the non- performing societies were of the opinion that lack of cooperation among the members of the society is one of the major reasons for the failure. Mahindapala (2020) found that individual factors and group dynamics have a bearing on the performance of the Tea Smallholding Development Societies (TSDS). Since most of the unsuccessful societies are dependent on exploitative trade channels to sell their produce, unfair price of green leaves adds to their vulnerability and affects their success and access to other services. Many of the non-performing societies reported that improper payment by the bought leaf factories is one of the causes for dysfunction (90%) and such improper payment led to disinterest among the members to continue as member of the society. Consequently, many members supplied green leaves either directly to the factories of their choice or to the tea agents depending upon the quantity and location of the farm. Other reasons cited by most of the members of societies for the organizational failures are improper maintenance of accounts, not conducting meetings regularly and lack of funds and not availing the subsidies from TBI. Since the meetings were not conducted on a regular basis, members have low levels of technical knowledge and business skills and they lack awareness about government support and face shortage of funds.

The prolonged crisis in the tea sector led to disinterest among the members. Even though in some societies the member numbers swell, due to remoteness and scattered nature of existence, they lack organization and bargaining capacity. Similar in the case of the Panbari Small Tea Growers Society at West Bengal, in which members enrollment decreased by 12% after a year of establishment and production declined at the rate of 6% every year. However, production of orthodox tea with own brand for export helped to succeed (Saha, 2020; Abdul Hannan, 2019). Studies by Katuwal (2020) and Karki., et.al. (2011) also demonstrated that membership enrollment, credit and targeting specialty tea markets are vital for success of the societies.

We found that the cost of production is increasing consistently both in the nominal and real terms widening the gap between the product price and the cost since the product price is declining as a result the parity is lost. At the prevailing green leaf prices, famers are incurring loss and they are not able to meet even the variable cost. Among various costs, labor cost accounts for around 85% of the unit cost of production and of the total labor cost, cost of plucking accounts for 55 to 75%, which is the major factor bringing down the profit margin. Further hikes in every other essential input including fertilizers, herbicides and pest control chemicals are reducing earnings and holding back investments in quality at a time when only good quality teas are competitive. The hike in cost of labor in tea manufacturing industries has also had a negative impact on STGs as it was estimated that an additional US$ 0.05/ kg for manufactured tea in NE Region of India and US$ 0.40/kg in South India had to be met in the last two decades resulting in downward impact on prices of green tea leaves (Pallavi and Liby, 2012).

The estimated green leaves production per year was 12,432 kg/ha in the case of performing societies, while it was 11,120 kg/ha in the case of non-performing societies (Table 8). Members of performing societies obtained 12% higher yield when compared to their counterparts mainly due to strict quality enforcement particularly the number of plucking per month and method of plucking. For example, the Eswarar Society is one of the prominent and awarded societies in the Nilgiris district, which is enforcing various quality parameters among the farmers for quality tea production. The members are supplied with soil health card to assess the status of the soil for optimum allocation of fertilizer inputs.

Since tea cultivation is one of the most labor-intensive activities, particularly plucking, cost-cutting measures would significantly reduce the cost of production and mechanization is one of the effective alternatives that can reduce costs. Functioning of Backward Bending Supply Curve (as real wages increase beyond a certain level, people will substitute leisure for paid worktime and so higher wages lead to a decrease in the labor supply) is compelling the STGs to resort to mechanization of their small tea gardens. Several initiatives on mechanization by Tea Board have been undertaken to reduce the cost of labor. Field survey estimates based on the Front-Line Demonstration by KVK- UPSAI (Ramamoorthy and Shanmugam, 2013) show that average harvesting cost by mechanical harvester was lower and two workers operating a mechanical harvester for a day can bring in the equivalent of leaf of 15 workers hand-plucking tea. Mechanically harvested tea bested hand plucked tea and tea obtained by shear-harvesting from a continuously sheared field over a prolonged period was found to be superior (www.worldteanews.com). On an average, members of performing society incurred US$ 0.13/ kg of green leave production, while it was US$ 0.15/kg in the case non-performing societies. The difference in cost of production between the two categories of societies is due to mechanization of harvesting in the case of performing societies. One of the reasons for better performance of the PPSs is sharing of harvesting machines among the members on custom hiring basis with nominal cost as a result the members of the performing societies realized higher productivity with lesser cost. Members of the performing societies realized a maximum price US$ 0.36/ kg of green leaves and minimum price of US$ 0.15/kg. On the other hand, the members of the non- performing societies received a maximum price US$ 0.35/kg and minimum price US$ 0.13/kg.

Collection of green leaves from each farm adds to cost of production and cutting down the margins for the members due to high transportation cost as STGs are scattered. Availing subsidy from tea board for purchase of vehicle is critical for their success as cost of transportation of green leaves from the collection center to factories sharply reduces marketing cost thereby the society can provide a better price for the members. Through our survey we found that 80% of the performing societies have their own vehicle for transportation of green leaves by availing 50% subsidy from tea board. On the contrary only 40% of the non-performing societies availed subsidy for purchase of own vehicle (Table 9). Similarly, performing societies benefitted more from various subsidies provided by tea board compared to non-performing societies.

The demand for the packaged varieties of the beverage in urban as well as rural areas is rising owing to the lesser chances of adulteration, superior quality, and convenient storage. People are willing to experiment with more tea blends, further providing an impetus for the growth of segments such as herbal, fruit, and other specialty varieties. The green tea segment is predicted to have a robust growth due to its vast consumption among health-conscious people and the urban population. Tea Board of India is giving a big push to organic tea production by providing 25% more subsidy than the normal subsidy of 30% and also 50% of the cost of certification will be paid as subsidy. Further, the Government of India under Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) implemented the organic tea cultivation program in 100 acres of tea gardens comprising of 100 Small Tea Growers (STG) through Department of Horticulture. Most of the times the price of tea leaves paid to the small tea growers is not sustainable for their livelihood, hence the concept of hand-crafted tea by the small producers need to be promoted and TBI have already been taken initiatives. Providing trainings to members of both the categories of societies so that the members are trained to handcraft the tea plucked from their own tea garden which makes this a cottage industry and thereby making them small entrepreneurs. These initiatives are helping the member-farmers of the societies to practice organic tea cultivation in order to improve income by realizing premium price. Improvement in the maintenance of quality standard in tea plucking, production of specialized tea by the small tea growers etc. would lead to a better price fetching mechanism and also better product demand. Thus, strategic approaches such as value addition, product diversification, integration of services through cohesiveness and collective practices through member’s cooperation are vital for effective functioning of the societies to insulate from price risks.

FUTURE POLICY/ STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS

The green leaf prices for the last one-decade hovering around US$ 0.10 to 0.18/kg, which is less than the cost of production. Even the district average price, fixed to ensure remunerative prices for the famers are always lower the cost of production. The prices realized for South and North Indian tea show that aberration in price of South India tea was higher compared to North Indian tea due to various factors particularly due to quality. Increasing cost of production of tea in STG tea sector coupled with fall in productivity putting downward pressure on profitability and income as the market prices for tea have been falling. Among the various reforms, prices paid to STGs as per the PSF show wider variations among the BLFs in various time periods. Strict enforcement of the policy and identification of those BLFs, which has been continuously paying the prices less than PSF and upgrading/modernization of those factories is critically important in order to improve their production capacity and efficiency in made tea production for better price realization so that the higher price realized is transmitted to the STGs. Monitoring of the societies to strictly to follow the bye-laws of society act, extension of subsidies like transport, collection sheds, pruning machines and others under various categories to weaker societies are very critical. There is a need for regulation and inspection of the tea factories by Tea Board to ensure better price realization and successful/effective functioning of the societies. The role of Primary Producers Societies (PPS) is critical in executing the quality in tea plucking and enforcing strictly the various pricing structure for various grades of green leaves in order to encourage the members to adopt the recommended packages of practices for production of quality green leaves.

To overcome the crisis since 1999, various measures have been implemented to mitigate the crisis to sustain tea production and bring in the decent livelihood to small holders. Among the several measures, production of organic tea is practiced for better price realization. These initiatives are helping the farmers to practice organic tea cultivation in order to improve income by realizing premium price. Though organic tea production is gaining momentum among the small tea growers, yield reduction after conversion is a major threat. Despite the fact that there is a yield reduction, our sample of organic tea growers were benefitted from higher remunerative price for their green tea leaves due to adoption of quality tea plucking practices with opinion that certification would help them to realize better prices due to market acceptance. As long as Small Tea Growers (STGs) could be able to realize premium market prices they are ready for conversion. It is also found that there is a long-term beneficial impact both in-terms of soil and crop productivity as evident from the soil sample analysis we did. Export price for organic tea is twice than that of normal tea but export share was minimal emphasizing the need for higher level of export for which formal certification is crucial since the organic tea exporters cannot source tea from uncertified STG organic farms. The awareness for certification is lacking though trainings and demonstration are being carried out by the various agencies. In this context of crisis of continuous price fall and losing the export markets due to competitiveness, organic production is one of the alternatives among the STGs to have decent livelihood. The role of Primary Producers Societies (PPS) is critical in enforcing the quality for organic tea production and marketing. Production of specialty tea like white tea and direct market linkages with export market for packed tea with a trademark were the key strategies adopted to insulate the price shock and that we observed only among few performing societies. The successful societies with higher coverage can resort to their own value addition by establishing micro and mini tea factories and creating their own trademark and marketing. The concept of hand-crafted tea by the small producers have already been promoted by TBI. Providing trainings to members of both the categories of societies so that the members are trained to handcraft the tea plucked from their own tea garden which makes this a cottage industry and thereby making them small entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Abdul Hannan (2019. Farm Size and Trade Relations of Small Tea Growers (STGs) in Assam and North Bengal. Social Change and Development. Vol. XVI No.2. pp 78 -99. Small Tea Growers in other states of India. teaworld.kkhsou.in/page-details.php

Annual Reports, 2014-15. www.teaboard.org

Eloise M. Biggs, Niladri Gupta, Sukanya D. Saikia, John M.A. Duncan (2018). Tea production characteristics of tea growers (plantations and smallholdings) and livelihood dimensions of tea workers in Assam, India. Data in Brief 17. 1379–1387 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dib

John Mano Raj, S (2020). Role of Market Intermediaries and Marketing Practices of Small Tea Growers in Assam. Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology. Volume XII, Issue III. Pp 209 to 217.

Karabi Das and Debarshi Das (2020). Technical Efficiency in Small Tea Gardens of Assam Review of Development and Change. 25(1). Pp: 112–130.DOI: 10.1177/0972266120916318 journals.sagepub.com/home/rdc

Karki A, L., Schleenbecker B, R., Hamm, U. (2011). Factors influencing a conversion to organic farming in Nepalese tea farms. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 112(2), 113–123.

Katuwal Narendra l (2020). Factors influencing small farmers’ participation in the extension of tea farming: a case of ilam, Nepal. EPRA International Journal of Agriculture and Rural Economic Research (ARER) - Peer-Reviewed Journal. Volume: 8 Issue: DOI: 10.36713/epra0813

Mahindapala, K.G.J.P (2020), Are Tea Smallholders’ Farmer Organisations in Sri Lanka Focused Towards Sectoral Issues? A Review on Present Status and Way Forward. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Review (JSSHR). Vol. 5, No. 3 (129-145) DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/jsshr.v5i3.66

Modalities and Scheme Guidelines of Tea Development and Promotion Scheme, 2021-2026, www.teaboard.gov.in

Pallavi, M., Liby, J. T. (2012). Comparative Analysis of Existing Models of Small Tea Growers in Tea Value Chain in the Nilgiris. NRPPD Discussion Paper. http://www.cds.edu/wp- content/uploads/2012/11/NRPPD20.pdf

Ramamoorthy, G., Shanmugam, R. 2013. Intervention and Impact of Machine Harvesting in tea among small farmers of Nilgiris District. www.upasikvk.org/download/intervention/harvesting.pdf

Saha Debdulal (2020). Producer collectives through self-help: sustainability of small tea growers in India International Review of Applied Economics. https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cira2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2020.1773646.

Selvaraj, K. N. and R. Ganesh (2017). Transformation to Organic Production among the Small Tea Holders for Sustainability – Myth or Reality? The 9th ASAE International Conference: Transformation in agricultural and food economy in Asia.11-13 January 2017 Bangkok, Thailand. Pp: 106 to 129.

Selvaraj, K.N. (2018). Price Sharing Formula and Price Realization by the Small Tea Growers in the Nilgiris District. Research Report (CARDS/OTY/AEC/2016/001). Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore