ABSTRACT

The northeastern part of Thailand is a significant area for quality rice cultivation, but it is constrained in topography, labor, and climate variability, resulting in low yield, high production costs, and unstable income. The proper policy option to settle such problems is the development of farmer knowledge in terms of production, marketing plans, and technology utilization by focusing on reducing the costs of production. In a change from past policy, the development of small-scale farmers should be emphasized, as this group currently obtains fewer benefits than large-scale farmers; this emphasis, for example, should include the promotion of quality rice, organic rice, or healthy rice by adding value to rice production in limited areas and reducing the effect from price fluctuation. In addition, the government should emphasize value-added processes by developing a variety of local rice types and Hom Mali (Jasmine) rice, to suit each local area, and using rice genetic diversity together with farmer strength as an advantage.

Keywords: Rice policy, rice yield, irrigation, cropping system, small-scale farmer

INTRODUCTION

Northeastern Thailand, also called “Isan” (Somnasang and Moreno-Black, 2000), is a region covering 160,000 square km. Except for a few hills in the northeastern corner, the region is primarily gently undulating land, most of it varying in elevation from 90–180 m, (Keyes, 1967). There are three seasons each year. The average temperature range is from 30.2 °C to 19.6 °C; the highest temperature recorded was 43.8 °C, and the lowest was 1 °C (TMD, 2010). Thus, while contributing to the biodiversity of the region, these hills also make the area more susceptible to droughts. Today, the low and erratic rainfall, nutrient-poor soils with poor moisture-retention capability, and sparse surface water combine to make the region difficult for wet-rice farming (Somnasang and Moreno-Black, 2000). Agriculture is the largest sector in the economy of the region. Rice is the main crop (accounting for about 60% of the cultivated land), but farmers are increasingly diversifying into cassava, sugarcane, and other crops (Chinese Consulate, 2019). Despite its dominance in the economy, agriculture in the region is extremely problematic. The climate is prone to drought, while the flat terrain of the plateau is often flooded in the rainy season. The tendency to flood renders a large proportion of the land unsuitable for cultivation. In addition, the soil is highly acidic, saline, and infertile from overuse. Since the 1970s, agriculture has been declining in importance at the expense of the trade and service sectors. Agriculture is the main economic activity, but due to the socioeconomic conditions and the hot, dry climate, output lags behind that of other parts of the country. The proportion of irrigated area is around 11% compared with 29% and 41% in the North and Central region, respectively (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018a). Most cultivated areas in the Northeastern region are located outside of irrigation zones and mainly depend on rainfall. This is Thailand’s poorest region; average wages are the lowest of the country. The region’s poverty is also shown in its infrastructure: eight of the ten provinces in Thailand with the fewest physicians per capita are in this region (Fund-Isaan, 2019; Gecko Villa Thailand, 2019). GDP per capita was 2,588 US dollar/year in the northeastern, while 8,605 US dollar/year and 16,126 dollar/year in the Eastern and Central region, respectively (NESDC, 2019)

Rice production is not only the main source for enhancing farm household income, but also important for food security of farm household in the northeastern part of Thailand. This region is a significant area for rice cultivation, encompassing more than 60% of the cultivated area of the country, and most farmers live in this region. Furthermore, the region is also the major area for cultivated Hom Mali[1] rice and glutinous rice; 85% of total Hom Mali rice and 90% of glutinous rice in Thailand are cultivated in this (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018a). However, with arid weather and a basin-like landscape, this region always suffers from natural disasters. Most of the cultivated area is a wet-season rice area, with no irrigation, having sandy soil and sandy loam with low fertility, which results in lowered rice yield when compared to other regions. In addition, price fluctuations and small cultivated areas lead to poverty and unstable income, which are the main issues for farmers in this region. In recent decades, policy instruments have been implemented to solve the problems of farmers, but such policies have been applied nationally, disregarding the problems of farmers in specific areas. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the problems in terms of production and marketing for farmers in the northeastern region, and to connect such problems to the implementation of proposed government policies for the development of the rice economy in this region.

RICE PRODUCTIVITY, VARIETIES, AND THE FARMING SYSTEM

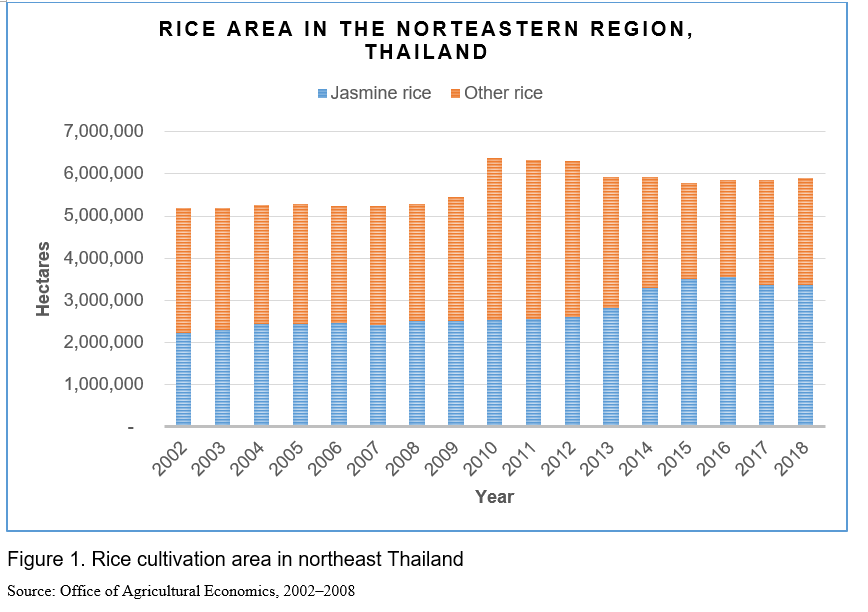

The northeastern Thailand rice cultivation region has a cultivated area of approximately 6.32 million ha, or 61.48% of the cultivated area in the country. There are two types of rice in this region: sticky rice for household consumption and Hom Mali ricefor sale. In 2002–2012, cultivated area in the region increased constantly, along with an increase in cultivated area in the country. It increased from 5.19 million ha in 2002 to 6.32 million ha in 2012, or an increase of approximately 22% over the decade. In particular, the area of Hom Mali rice has tended to increase constantly over more than two decades, showing an increase from 2.23 million ha in 2002 to 3.37 million ha in 2018 (Figure 1). Because of the quality of Hom Mali rice, it commands a dominant position in price and marketing demand. In addition, the rice pledging scheme for cultivating Hom Mali rice is more advantageous than for other rice, which incentivizes farmers to cultivate more.

There are two varieties of Hom Mali rice cultivated in Thailand especially in the northeastern region: KDML105 and RD15. Both cultivars are photosensitive, and the paddy has a straw color; the long-grain, clear brown rice has a tip seed that is slightly curved, glossy, and containing a small germ of good quality. It has a low level of amylose at 12–16%. After cooking the rice will be sticky, soft, and will have a good aroma. This region has proper soil series for Hom Mali rice, which are the Roi-et series, Roi-et loam series, Kula Ronghai series, Tha Tum series, and Nakhon Phanom series. Soil series and climate in this region produce quality Hom Mali rice. Additionally, there is rock salt underground because this area used to be a sea in a primitive era; thus, soil salinity and drought give Hom Mali rice a better smell and cooking quality than Hom Mali rice from the other regions (Srisompun et al., 2014). Most farmers in the northeast mainly cultivate for their household consumption, resulting in the selection of varieties based on long grain, good cooking quality, and fragrance. The RD6 cultivar is popular for sticky rice because it has a good aroma, long grain, and high yield, as well as resistance to diseases and insects. The government also encourages farmers to cultivate wet-season rice on account of high yield and marketing demand, so the cultivated area for RD6 rice is constantly expanding. The currently cultivated area for RD6 is 79.72% of the total sticky rice area in all regions; the RD10 and other RD cultivars make up approximately 2%; and other cultivarss such as Niaw Ubon, Hom Sakon, San-pah-tawng, Gam Pai15, and Hahng Yi 71 total approximately 18% (Srisompun, 2012).

More than 90% of rice cultivation in the northeast is categorized as wet-season rice. Every year, farmers will start preparing soil in April, and cultivation in May–June depends on the duration and amount of rainfall in that year. Dry-season rice is limited because of the lack of water and irrigation. Aging farmers and a labor shortage in the agricultural sector have led to a greater use of broadcast rice fields rather than transplanted rice fields. Soil preparation is commonly done with small four-wheeled tractors rather than by hand, as it saves time. Wet-season rice cultivation does not use chemical sprays, as these may leave residues in products and they are harmful to farmers’ health. Farmers use machine harvesting (combines) rather than harvesting by hand. Most Hom Mali rice is sold for household income, but sticky rice is stored until farmers can ensure that they have enough rice for cultivation next year as well as for household consumption through the year; the remainder is then sold.

KEY PROBLEMS AND CONCERNS

Low productivity and small farm size

Because most of the cultivated areas in the northeast belong to the wet-season rice region, there is no irrigation, and many areas suffer from frequent drought, and the fields are sandy and sandy loam. Thus, farmers will select photosensitive rice varieties that are well resistant to agricultural pests and drought. Therefore, the average yield is lower than in the north and central regions; for example, in the northeast the Hom Mali rice yield is 2,225 kg/ha on average, while the central and southern regions have average Hom Mali rice yields of 3,113 and 2,300 kg/ha, respectively (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2016). Because low rice yield has a direct impact on farmers’ income, and Hom Mali rice is the main cash crop for household income, low margins of production together with small cultivated areas then cause poverty and unstable income. These are the main issues that require policy solutions.

The northeastern region has a rice cultivation area of approximately 6.32 million ha and approximately 2,773,651farming households (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018a). Most of these are small-scale farmers, having a cultivated area of approximately 2.28 ha per household. In principle, large-scale farms will have low unit cost; benefiting from the economy of scale, the average cost per unit of production decreases as the size of the farm increases. These economies can occur because the farmer is able to spread more production over the same level of fixed expenses. Economies of size can also occur when a farm is able to obtain volume discounts for inputs such as seed or fertilizer (Duffy, 2009). However, an analysis of profit over cash costs for rice cultivation in the northeast shows that the small-scale farmer (rice cultivated area < 1.60 ha) has an average production cost that is lower than for the large-scale farmer, even though large production should receive benefits from the economy of scale in production. Another reason is that wet-season rice in the northeast uses less fertilizers and chemical products than in the other regions, as these farmers focus more on household consumption. On the other hand, large-scale farmers need to hire labor for almost all activities, but as a result of labor shortages and aging farmers, this produces high costs (Srisompun et al., 2019a). Hence, technology and small machinery development can reduce the increase of production costs in the large-scale farming model. This should be a proper option for farmers in this region and will be discussed further.

Irrigation system

A shortage of water supply for agricultural activities has been a major problem facing northeastern farmers. This region has a total cultivated area of approximately 10.22 million ha and irrigation systems for 1.14 million ha, or 11% of the region’s cultivated area (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018).Cultivated area for dry-season rice is an indicator for sufficient irrigation. The northeast has an area for dry-season rice of 226,220 ha, or 3.86% of total cultivated area, which is quite low when compared with the north (33.94%) and central (44.99%) regions. Most cultivated areas are located outside of irrigation zones and mainly depend on rainfall; this factor is responsible for lower yield than in other regions, and the government is also concerned about this problem. For the last half century, much attention and funds have been channeled into the development of water resources in northeast Thailand. This drive to develop irrigation infrastructure has been spread across technical scales (large, medium, and small), types of techniques (storage/gravity, run-of-river diversions, pump-irrigation, small-scale tanks), and bureaucratic institutions (Floch and Molle, 2013). The Royal Irrigation Department attempts to increase irrigation zones in the region and has implemented a development project over the 2007–2022 period for a potential irrigation zone. This zone, located in the northeast, covers more than 50% of the irrigation development project zone in Thailand or approximately 3.44 million ha. Project descriptions indicate the construction of large and small reservoirs, a check dam, a floodgate for water retention during cultivation, and construction of an electric pumping station (Knoema, 2017). Prior to 2006, the irrigation zone in the northeast was 521,513 ha; in 2006 this zone increased to 976,389 ha (Lam nam oon Irrigation project, 2006), and in 2017 it increased to 1,139,049 ha (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018). Even though the irrigation zone has been increased more than twice from the past, it still has a low proportion when compared with the other regions. A significant constraint for developing irrigation systems in the northeast is that internal water resources are ill suited for the development scenarios envisioned by planners and decision makers. There is a low runoff-to-rainfall ratio and a mostly flat and undulating topography, which puts considerable limits on surface water storage and gravity diversions (Molle et al., 2009).

Climate change: drought and flooding

As mentioned, most rice cultivation in the northeastern region is done outside irrigation zones and mainly depends on rainfall and climate. Rainfall in each year will affect both quantity and quality of rice in this region. Currently climate variability causes unstable seasons and rain scattered during the year; temperature and rainfall fluctuate as well, and extreme events often occur and are more severe. This region always suffers from drought, which is an important constraint to crop production in northeast Thailand. This region has been frequently subjected to drought as a result of the erratic distribution of rainfall, dry spells in the rainy season, and low water-holding capacity of soils. Thirteen out of 34 years during the period 1970–2004, namely 1972, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1987, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998, and 2004, were drought years in northeastern Thailand (Prapertchop et al., 2007). The mean annual rainfall over the 2001 – 2011 period was 1,462 mm while the mean annual rainfall over the 2011 – 2019 period was 1,348 mm. Furthermore, in the drought year 2012, mean annual rainfall declined 239 to 375 mm, in comparison with mean annual rainfall over the 2001–2011 time periods in the selected site study. Rice is the main crop affected by drought. The yield loss due to drought was about 55–68% of rice cultivated in the study site (Polthanee et al., 2014). According to Gypmantasiri et al. (2003), 19% of northeast Thai farmers experienced drought while growing rice at the planting stage, and 40% of them at the tilling stage, although another 23% reported that drought could affect rice growth at any growing stage. The rice yield reduction caused by drought will become more serious in the future (Prabnakorn et al., 2018).

Other than drought, flooding is another important problem, where farmers in the lowland northeast have suffered in the past decade, as the topography is a basin. The area for growing lowland rice is approximately 528,000ha (Rice Department, 2016). In the past decade, northeastern farmers, especially in low land areas, experienced flooding and damaged rice production five times in a decade: 2010, 2011, 2013, 2017, and 2019. The severity of the damage to rice fields and the effect on farmers depend on flood duration and the size of the affected area. For example, the latest flood in 2019 caused damage to 363,200 ha of rice fields in the northeast, and rice production was lower than estimated by1–1.1 million tons (Prachachat, 2019). Climate variability that damages agricultural products has a direct impact on farmers’ lifestyle, who are sensitive because they have less income and high debt.

Labor shortage and aging farmers

The expansion of industrial and service segments has increased the labor demand for non-agricultural segments, and wages in these segments are higher than agricultural wages. There is therefore a move of labor from agricultural to other segments (OAE, 2016). Moreover, the average age of northeastern farmers increased continuously from 51.3 years old in 1987 to 54.70 years old in 2019 (Butso, 2010; Srisompun et al., 2019a). An increase in the average age of farmers confirms a worry that new generations do not want to be farmers (Patmasiriwat, 2010). Most young people who have grown up in farmer families in Thailand do not want to be farmers. In their perspective, rice farming is a career that involves working hard in the field all day and earning little money. Consequently, farming is not considered as a worthy profession. Furthermore, most farmers believe that being a rice farmer indicates a lower social status. As a result, they attempt to encourage their offsprings away from the farm. Therefore, when their children face career choices, non-agricultural options are highly encouraged by the parents (Tapanapunnitikul and Prasunpangsri, 2014).

Currently, the result is a labor shortage arising from the absorption of labor into the industrial and service segments and the aging farmer issue; these factors push the adoption of agricultural machinery to replace human beings in the entire rice production process (Soni, 2016). Most farmers use small four-wheeled tractors for plowing, instead of the labor of draft animals and hand tractors of the past, robotic chemical spraying machines instead of hand sprayers, and combine harvesters instead of the labor of human beings and draft animals to carry out threshing(Poapongsakorn, 2011; Napasintuwong, 2017). According to Srisompun et al. (2019a), the rice yield, labor usage, labor productivity, and farm revenue of farmers in the northeastern region vary by mechanization level. The high use of rice production machinery has caused a decrease in farmers’ net profit because of the effect of the decreased average yield.

Increase of production costs

Labor shortages in the agricultural sector and the aging of farmers generate high labor wages in this sector. Farmers have to use agricultural machineries instead of human labor in almost all activities of production such as tillage, cultivation, and harvest. And production cost needs to include the increase of fertilizer cost as well. Regarding the seed source, Napasintuwong (2018) indicated that farmers in the region had more than one source of seeds, most of them kept their own seeds for following crops, farmers' groups, cooperatives and Community Rice Center (CRC) were the key sources of seeds in the regions, and public institutes played an important role in providing seeds to farmers. Most of them replaced their seeds within two to three crop years, , and they have to buy new seeds; only a few of them select seeds from their field for further use. These factors lead to high production costs for farmers in this region. Production costs increased from 6.06 Baht/kg in 1987 to 10.49 Baht/kg in 2013(Butso, 2010; Srisompun et al., 2014), or increased more than 73.10% in 28 years, while the average rice yield for this region has changed only slightly. Thus, the average income per household from rice cultivation has decreased.

Price fluctuation

In the past, prices have lightly increased, and farmers have always suffered from price fluctuations, especially northeastern farmers, who grow Hom Mali rice and RD6, which are photosensitive. So this is a key limitation; because of the photosensitivity, rice grows only once a year (in the wet season) and should be harvested during the same year (November–December). Because large amounts of harvested Hom Mali rice enter the market at the same time, the farmers are forced to sell their rice at a low price during the harvest period (Thongngam, 1999). However, because the demand for rice persists throughout the year in Thailand, the price of rice increases after the harvest season and peaks between April and July (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018). Accordingly, if the farmers store their rice and sell it between April and July, they can earn higher incomes than those earned from selling their rice during the harvest season; consequently, they can achieve maximum profits (Thongnit, 2008). However, most farmers in the northeast choose to sell their rice immediately after harvest, preferring to sell freshly harvested rice instead of storing the rice for later sale (Srisompun et al., 2019a), due to household expenditures and the shortage of agricultural labor (Srisompun et al., 2014).

KEY POLICY IMPLEMENTATIONS

Large-scale farming model

In 2015, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives of Thailand launched the first phase of a newly initiated program called the “large-scale farming model.” This aimed to improve production efficiency and competitiveness by reducing production costs, increasing yields, and aligning production with market demand. The program, however, has experienced several problems that may severely undermine its future prospects, including a lack of well-rounded managers, land fragmentation, poor water management, weak governance, farm debts, enticing benefits in the short run, and equity issues (Duangbootsri, 2018). Large-scale farming has more than 6,000 groups with 405,205 households, and the northeast has 3,016 groups with 233,155 households or more than 50% of large-scale farming in the country (Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2019). However, the number of household farming in the northeast has around 3.42 million households, the share of participated farmer is around 6.83% of total farmers in the region. Thirapong (2019) mentioned that significant problems of farming are that farmers in this area are aging and operate at small scale, which encouragement and management for cultivation are difficult. This is an important issue that has a direct impact for large-scale farming. The appropriate option should be improving skills and competences of the leader farmers in the region by introducing a training programme, and enhance the dissemination and transfer of knowledge and innovation is necessary for the project to be successful. Further, relevant officers still misunderstand in terms of promotion of large-scale farming and lack of marketing promotion and information access; in addition, there is redundancy between related government agencies. Besides, rice farming does not have the production structure that allows a scale advantage to take place. As a result, it is unlikely that the program can be sustained in the long run after the government’s subsidy is withdrawn. Policymakers should also be cautious about the impact that the program could have on rural inequality. Specifically, the program may widen the inequality gap in rural areas because it tends to favor large farms while discriminating against small farms (Duangbootsri, 2018).

Flooding and drought support program

In the past decade, northeastern farmers have suffered from natural disasters every year, whether flooding or drought. Government policy has provided continuous support, with an increase in the budget especially during the year that problems spread to many provinces. But government subsidies may not solve this problem in the long run. Other than efforts from governmental agencies or other institutions to solve this long-run problem, other means such as research and development of short-growth rice (RD51) have been implemented. This type of rice has to be harvested prior to flood season. RD51 developed from KDML105; it is resistant to sudden flood, as it can straighten the internode up above water, and it is resistant to floods during the tillering stage (from sowing until 60 days past planting). The cooking quality is similar to KDML105 (BIOTEC, 2013), but its weaknesses are susceptibility to rice blast disease, bacteria leaf blight disease, gall midges, and plant hoppers, and therefore it is not popular. In addition, an integrated assistance project has been implemented for farmers who suffer from drought by encouraging them to grow plants that use less water or to raise animals instead of cultivating dry-season rice where northeastern farmers in an irrigation zone are likely to adapt better than in other regions. Evaluation of this project has found that it is quite delayed, and farmers are not supported for seeds or animals; this does not meet their requirements, as it is a national large project and implemented at the department level. Such projects should be implemented at the provincial level rather than the central level in order to avoid the delay, and farmers may then adapt as appropriate by choosing to cultivate a rotation crop or raise animals (Chaowagul et al., 2016).

Crop rotation

More than 80% of the northeastern area depends on rainfall. There the crop product has low efficiency because the area is improperly used and is constrained by resources and the environment. Farmers have few production options and a lack of diversity, which leads to low income, lack of stability in an agricultural career, lack of strength in the community, and poor quality of life. In addition, the production structure depends on a few main crops; these are mostly rice, cassava, and maize. If any year has a low yield, this will have a great impact on farmers’ income. Growing post-harvest crops such as through a rotation of rice–peanut, rice–cassava, or rice–corn will provide higher yield than growing rice in a mono crop system (Boonpradub et al., 2016). The objective is not only to raise income for farmers and reduce the dependence on rice cultivation, but also to reduce plant disease and improve soil quality in rice fields by growing crops in rotation. The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives always encourages farmers in this region to grow crops in rotation post-harvest, for example by encouraging farmers to grow forage plants, plants that use less water, or to adopt integrated farming by arranging crops to suit each local area, which can increase production efficiency. The significant issue for this policy is that farmers are unable to select crops or animals, as it has been specified from the central sector regardless of farmers’ actual desires. Further, their products have few buyers and there is no local market support. Therefore, farmers must sell their products at a lower price than actual production cost (Chaowakul et al., 2016). Greater marketing familiarity for farmers is important, and this should be a part of the project to promote crop rotation. Events for farmers to meet agricultural product representatives or buyers should be set up prior to planting season in order to exchange information between farmers and prospective buyers; this will provide farmers with more knowledge on agricultural marketing.

Community Rice Center (CRC)

The Community Rice Center is a farmer organization by which the Rice Department and the Department of Agriculture Extension cooperate to enhance the development of rice production. The major aim is the production and distribution of quality rice seed in the community; the quality seed should be met with the minimum standards of Plant Varieties Act or seed law. In addition, it is a center to transfer rice production technology by focusing on farmers’ knowledge and the ability to improve themselves to be self-reliant. This center has operated since 2000 under the Department of Agriculture Extension, and since 2006 it has been operated by the Rice Department. In 2019 there were 1,786 Community Rice Centers registered with the Rice Department. These centers are located in many major production areas in the country, and they provide farmers with good quality rice seeds in the amount of approximately 100,000 tons per year (Rice Department, 2019). Promotion policies of Community Rice Centers in the northeastern region not only increase the quality of rice seeds but also increase farmer income from rice seed production.

Rice pledging scheme

The rice barn pledging scheme aims to prevent the release of quantities to the market that are in excess of demand, thereby maintaining stability and raising prices. This scheme gives farmers the choice to store their rice and improve their paddy quality, to yield a higher price. The barn-pledging scheme began with the 2014/15 crop year. The farmer could bring Hom Mali and sticky paddy to apply for a loan from the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC) for 90% of the market price. The credit limit could not exceed 300,000 baht without interest, and there was an additional 1,000 baht per ton for farmers who stored rice in their barn more than 30 days as a motivation to delay disposing of rice on the market during the harvest season. Farmers had to repay their loans within 4 months of receipt. The scheme has operated continuously until the present. To increase the motivation to participate in the scheme, the paddy storage fee was raised to 1,500 baht per ton for participating farmers in production year 2017/18, but participation is still lower than targeted (target production is 2 million tons), results in a high proportion of the total rice product being released to the market (Srisompun et al., 2020). Most of the northeastern farmers who participate in this project are large-scale farmers with cultivated area of more than 4.8 ha. The small-scale farmers have to kept their rice product for home consumption, so they have not enough paddy for participating in the rice-pledging scheme . This scheme is of benefit mostly for large-scale farmers, but small-scale farmers should have other options.

FUTURE OUTLOOK

There are several problems with policy implementation to assist northeastern farmers. This study has produced some recommendations for policy improvement:

- Large-scale farming is constrained especially in the northeastern region as farmers will not benefit from economies of scale. Larger farms will have higher cash costs because they have to hire more labor. Support by means of labor-saving machinery to small-scale farmers may be the appropriate policy choice to relieve the regional constraints.

- Subsidies provided for drought or flooding do not solve the problem in the long run, as they do not encourage farmers to adapt. Educating farmers on rainfall variability, number of rainy days, using short-growth rice, development of rice seed that is resistant to drought or flood, and growing plants that use less water or raising animals will assist farmers in adapting and reducing the effects of such problems in the long run.

- Encouragement of crop rotation needs to be accompanied by the development of a crop rotation market along with promotion and proper production knowledge for farmers. As in the past, there have been major implementation problems in alternative crop markets. This issue will be solved effectively if the government plans for marketing connections before determining the alternative crop for each area.

- The development of Community Rice Centers is helpful for farmers in this region, and if the rice seed in the market is insufficient for demand, it should be expanded. However, rice seed represents another cost that is subject to increase. Thus, transferring production technology of quality rice seed to non-members of the center will be another way to reduce production costs.

- Development of small agricultural machinery is important for solving the labor shortage in the agricultural sector and reducing the high production cost of rice cultivation in the northeastern region. This could reduce the production cost especially in preparing soil and harvesting.

- A few farmers have participated in the barn pledging program, but most of the participating farmers have been large-scale farmers. Small-scale farmers should have other options, for example production promotion for quality rice or organic rice, healthy rice, and local rice in order to add value to rice production in limited areas.

CONCLUSIONS

The northeastern region of Thailand is a significant area for quality rice cultivation. Rice is not only the main household income for small-scale farmers, but it also is important as the staple food for this region’s population. Yet constraints in the form of irrigation, topography, climate variability, and labor present continuous and long-term problems. These include low yield and productivity, high production costs, price fluctuation, and poverty. While the government has policy measures to assist farmers, many policies do not provide benefit for farmers in this region who are poor and have limited access to utilities. The growth of urban population centers has left farmers in this region operating at small scale and with limited cultivated area. Therefore, policy options should include support for labor-saving machinery to small-scale farmers and the development of knowledge both in production and marketing. Such knowledge should include the benefit of technology for farmers, by focusing on production that reduces cost such as through small agricultural machinery and production of quality rice seed. Development for small-scale farmers is necessary, as this group receives fewer benefits than large-scale farmers. If production promotion is offered for quality rice or organic rice, healthy rice, and local rice, this could add value to production in limited areas. Further, the government should focus on value-added rice in the northeastern region by developing varieties of local rice and Hom Mali rice to suit each local area, as well as colored rice and healthy rice. The genetic diversity of rice in the region could be of great advantage to local farmers.

REFERENCES

BIOTEC. 2013. New Variety of Rice Resistant to Sudden Flood “RD51” Certified Variety from Rice Department. (http://www.biotec.or.th/th/index.php.; Accessed 15 February 2020). (In Thai)

Boonpradub, S., C. Cheangauksorn, P. Muangphet, P. Phangchun, B. Phanpeng, S. Jaichit, P. Peabying, and S. Chuthammathat. 2016. Research and Development on Sustainable Cropping Systems in Rainfed Area http://www.doa.go.th/research/attachment.php?aid=2270. (In Thai)

Butso, O. 2010. Efficiency change and resource use in Thailand Rice Production: Evidence form Panel Data Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Kasetsart University, Thailand.

Chaowagul, M., S. Rungsipathra, O. Sirisomphan, and C. Choesawan. 2016. Final report “The Adaptation to drought of rice farmers in irrigated areas with evaluation on integrated mitigation project to farmers affected by drought project”. Thailand Research Fund. (In Thai)

Chinese Consulate. 2019. Northeastern Thailand: Brief introduction. (http://khonkaen.china-consulate.org/eng/lqgk/.; Accessed 15 February 2020).

Duangbootsri, U. 2018. Thailand’s Large-Scale Farming Model: Problems and Concerns. Agricultural Policy Platform. (http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=932: Accessed 15 February 2020).

Duffy, M. 2009. Economies of Size in Production Agriculture. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 4(3-4): 375–392. doi: 10.1080/19320240903321292.

Floch, P. and F. Molle. 2013. Irrigated Agriculture and Rural Change in Northeast Thailand Irrigated Agriculture and Rural Change in Northeast Thailand: Reflections on Present Developments. In book: Governing the Mekong: Engaging in the politics of knowledge (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283720675_Irrigated_Agriculture_and_Rural_Change_in_Northeast_Thailand_Irrigated_Agriculture_and_Rural_Change_in_Northeast_Thailand_Reflections_on_Present_Developments; Accessed 25 February 2020).

Fund-Isaan. 2019. Why Isaan. (https://fund-isaan.org/content/why-isaan; Accessed 15 February 2020).

Gecko Villa Thailand. 2019. General Background Information and Specific Details on Northeast Thailand. (https://www.geckovilla.com/thailandfacts.html.; Accessed 12 February 2020).

Gypmantasiri, P., B. Limirankul, and C. Muangsuk. 2003. Bio-physical and Socio-economic Characterization of Rainfed Lowland Rice Production Systems of the North and Northeast of Thailand.(http://www/mecweb.agri.cmu.ac.th/agsnst/publication;Accessed 28 February 2020).

Keyes, C. F. 1967. Isan: Regionalism in Northeastern Thailand. Cornell Thailand Project; Interim Reports Series, No. 10 (PDF). Ithaca: Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University.(https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/57533/065.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.; Accessed 12 February 2020).

Knoema. 2017. Thailand - Total area equipped for irrigation. (https://knoema.com/atlas/Thailand/topics/Land-Use/Area/Total-area-equipped-for-irrigation; Accessed 2 March 2020).

Lam nam oon Irrigation project. Royal Irrigation Department. 2006. Summary of Irrigation Zone and Former Intercepted Storage and Newly Collected for Each Region and Irrigation Office (http://www.namoon.go.th/water_resources4.htm; Accessed 10 March 2020). (In Thai)

Napasintuwong, O. 2018. Rice seed system in Thailand. (http://agri.eco.ku.ac.th/RePEc/kau/wpaper/are201804.pdf, Accessed 13 April 2020).

NESDC. 2019. Gross Reginal and Provincial Product. (https://www.nesdc.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=5628&filename=gross_regional ; Accessed 10 March 2020). (In Thai)

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2019. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives Encourages Large-scale Farming. (https://www.moac.go.th/news-preview-412891791039; Accessed 10 March 2020). (In Thai)

Molle F., P. Floch, B. Promphaking, and D.J.H. Blake. 2009. “‘Greening Isaan’: Politics, Ideology, and Irrigation Development in Northeast Thailand.” In Contested Waterscapes in the Mekong Region, ed. Molle et al. (https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers16-05/010050257.pdf; Accessed 10 March 2020).

Office of Agricultural Economics. 2016. Elderly Agricultural Labor Trends, Skilled Labor Suggested, Welfare Providing and Applying Technologies. (http://www3.oae.go.th/zone2/index.php/news/16-oae-news/68-2016-02-15-01-...., Accessed 14 March 2020). (In Thai)

Office of Agricultural Economics. 2018a. Agricultural Statistic of Thailand 2018. (http://www.oae.go.th/view/1/Publications/EN-US; Accessed 18 February 2020). (In Thai)

Office of Agricultural Economics. 2018b. Plantation Area, Crops, Crops per Rai, and Farm Price of Thai Hom MaliRice in 2008-17.(In Thai)

Paopongsakorn, N. 2011. The political economy of Thai rice price and export policies in 2007–2008. in D. Dawe (ed.), Rice Crisis: Marker, Policy and Food Security, FAO and Earthscan, Washington, D.C.

Patmasiriwat, D. 2010. Book review: Readings in Thailand Rice Economy: A Collection Book in Honor of Associate Professor Somporn Isvilanond, ed. by Ruangrai Tokrisana et al. Department of Agricultural Economics and Resource Economics, Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University, 2009, 150pp. Journal of Economic and Public Policy, 1(1), 183–187. ( file:///C:/Users/CCS_LP/Downloads/74916-Article%20Text-178482-1-10-20170116.pdf., Accessed 14 March 2020). (In Thai)

Polthanee, A., Promkumbut, A., and Bamrungrai, J. 2014. Drought Impact on Rice Production and Farmers’ Adaptation Strategies in Northeast Thailand. International Journal of Environmental and Rural Development 5-1: 45-52.

Prabnakorn, S., M. Shreedhar, F.X. Suryadi, and C.D. Fraiture. 2018. Rice Yield in Response to Climate Trends and Drought Index in the Mun River 2 Basin, Thailand. Science of the Total Environment 621: 108-119. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.136.

Prachachat. 2019. Flooding Crisis in Isan Damaged 8 Billion Affect Economic Area-Agriculture 2 Million Rai-4 Provinces Still in Crisis (https://www.prachachat.net/local-economy/news-371872, Accessed 14 March 2020). (In Thai)

Prapertchop, P., Bhandari, H., and Pandey, S. 2007. Economic Cost of Drought and Rice Farmers’ Coping Mechanism in Northeast Thailand. In: Economic Cost of Drought and Rice Farmers’ Coping Mechanisms: A Cross Country Comparative Analysis. Pandey, S., Bhandari, H., Hardy, B. (eds). International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines, 116-148.

Rice Department. 2016. Report on Rice Cultivation in 2016/17 Round 1 (http://www.ricethailand.go.th/web/home/images/brps/text2559/15092559/15092559.pdf, Accessed 14 March 2020) (In Thai)

Rice Department. 2019. Rice Department Seminar “Community Rice Center” Large-scale Farming in 2019 Driven by Thousands of People. (http://www.ricethailand.go.th/web/index.php/mactivities/3988-2018-08-15-03-50-12, Accessed 14 March 2020). (In Thai)

Somnasang and Moreno-Black. 2000. Knowing, Gathering and Eating: Knowledge and Attitude about Wild Food in Isan Village in the Northeastern Thailand. Journal of Ethnobiology 20(2): 197-216.

Soni, P.2016. Agricultural Mechanization in Thailand: Current Status and Future Outlook. Agricultural Mechanization in Asia, Africa, and Latin America 47(2): 58-66.

Srisompun, O. 2012. Final Report on the Project of Thai Glutinous Rice under AEC. Thailand Research Fund, Rama copy one, Inc., Khon Kaen, Thailand. (In Thai)

Srisompun, O., Charoenrat, T., and Thipayanet, N. 2014. Final Report on the Project of Production and Marketing Structures of Thai Jasmine Rice. Thailand Research Fund, Ramacopyone, Inc., Khonkaen, Thailand. (In Thai)

Srisompun, O., A. Thanaporn, and S. Isvilanonda. 2019. The Adoption of Mechanization, Labour Productivity and Household Income: Evidence from Rice Production in Thailand. TVSEP Working Papers wp-016, Leibniz Universitaet Hannover, Institute of Development and Agricultural Economics, Project TVSEP.

Srisompun O., S. Simla, and S. Boontang. 2019a. Storage Decision of Jasmine Rice Storage of Jasmine Rice Farmer in Thailand. Journal of the International Society for Southeast Asian Agricultural Sciences 25 (1): 80-91.

Srisompun O., S. Simla, and S. Boontang. 2019b. Production Efficiency and Household Income of Conventional and Organic Jasmine Rice Farmers with Differential Farm Size. Khon Kaen Aricultural Journal 47 supplementary (1): 857-862. (In Thai)

Srisompun, O., Simla, S. and S. Boontang. 2020. Influential Factors for the Decision to Participate in a Rice-pledging Scheme: Evidence from Jasmine Rice Farmers in Northeast Thailand. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, (in press).

Tapanapunnitikul, O., and Prasunpangsri, S.2014. Entry of Young Generation into Farming in Thailand. FFTC Agricultural Policy Articles. (http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=330., Accessed 14 March 2020).

Thirapong, K. 2019. The Large Agricultural Land Plot Program and The Context of Thailand’s Agriculture. (http://www.ecojournal.ru.ac.th/journals/23_1516971978.pdf, Accessed 14 March 2020). (In Thai)

Thongnit, N. 2008. An Analysis of Farmer’s Return under Paddy Pledging Scheme Crop Year 2005/06. M.S. Thesis, Kasetsart Univ. Bangkok, Thailand. (In Thai)

Thongngam, K. 1999. Analysis on Jasmine Rice Distribution in Chaing Mai Province. CMJE. 13: 55-73.

TMD. (2010). The Climate of Thailand. (https://www.tmd.go.th/en/archive/thailand_climate.pdf., Accessed 14 March 2020). (In Thai)

[1] Hom Mali rice or Jasmine rice is the rice variety that native to Thailand, this is a long-grain variety of fragrant or aromatic rice. It is fragrance and reminiscent of pandan when cooking. There are two cultivars of Hom Ma Li rice in Thailand, KDML105 and RD15, both are photosensitive cultivars which grown one crop per year only in the wet season.

Rice Economy in Northeast Thailand: Current Status and Challenges

ABSTRACT

The northeastern part of Thailand is a significant area for quality rice cultivation, but it is constrained in topography, labor, and climate variability, resulting in low yield, high production costs, and unstable income. The proper policy option to settle such problems is the development of farmer knowledge in terms of production, marketing plans, and technology utilization by focusing on reducing the costs of production. In a change from past policy, the development of small-scale farmers should be emphasized, as this group currently obtains fewer benefits than large-scale farmers; this emphasis, for example, should include the promotion of quality rice, organic rice, or healthy rice by adding value to rice production in limited areas and reducing the effect from price fluctuation. In addition, the government should emphasize value-added processes by developing a variety of local rice types and Hom Mali (Jasmine) rice, to suit each local area, and using rice genetic diversity together with farmer strength as an advantage.

Keywords: Rice policy, rice yield, irrigation, cropping system, small-scale farmer

INTRODUCTION

Northeastern Thailand, also called “Isan” (Somnasang and Moreno-Black, 2000), is a region covering 160,000 square km. Except for a few hills in the northeastern corner, the region is primarily gently undulating land, most of it varying in elevation from 90–180 m, (Keyes, 1967). There are three seasons each year. The average temperature range is from 30.2 °C to 19.6 °C; the highest temperature recorded was 43.8 °C, and the lowest was 1 °C (TMD, 2010). Thus, while contributing to the biodiversity of the region, these hills also make the area more susceptible to droughts. Today, the low and erratic rainfall, nutrient-poor soils with poor moisture-retention capability, and sparse surface water combine to make the region difficult for wet-rice farming (Somnasang and Moreno-Black, 2000). Agriculture is the largest sector in the economy of the region. Rice is the main crop (accounting for about 60% of the cultivated land), but farmers are increasingly diversifying into cassava, sugarcane, and other crops (Chinese Consulate, 2019). Despite its dominance in the economy, agriculture in the region is extremely problematic. The climate is prone to drought, while the flat terrain of the plateau is often flooded in the rainy season. The tendency to flood renders a large proportion of the land unsuitable for cultivation. In addition, the soil is highly acidic, saline, and infertile from overuse. Since the 1970s, agriculture has been declining in importance at the expense of the trade and service sectors. Agriculture is the main economic activity, but due to the socioeconomic conditions and the hot, dry climate, output lags behind that of other parts of the country. The proportion of irrigated area is around 11% compared with 29% and 41% in the North and Central region, respectively (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018a). Most cultivated areas in the Northeastern region are located outside of irrigation zones and mainly depend on rainfall. This is Thailand’s poorest region; average wages are the lowest of the country. The region’s poverty is also shown in its infrastructure: eight of the ten provinces in Thailand with the fewest physicians per capita are in this region (Fund-Isaan, 2019; Gecko Villa Thailand, 2019). GDP per capita was 2,588 US dollar/year in the northeastern, while 8,605 US dollar/year and 16,126 dollar/year in the Eastern and Central region, respectively (NESDC, 2019)

Rice production is not only the main source for enhancing farm household income, but also important for food security of farm household in the northeastern part of Thailand. This region is a significant area for rice cultivation, encompassing more than 60% of the cultivated area of the country, and most farmers live in this region. Furthermore, the region is also the major area for cultivated Hom Mali[1] rice and glutinous rice; 85% of total Hom Mali rice and 90% of glutinous rice in Thailand are cultivated in this (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018a). However, with arid weather and a basin-like landscape, this region always suffers from natural disasters. Most of the cultivated area is a wet-season rice area, with no irrigation, having sandy soil and sandy loam with low fertility, which results in lowered rice yield when compared to other regions. In addition, price fluctuations and small cultivated areas lead to poverty and unstable income, which are the main issues for farmers in this region. In recent decades, policy instruments have been implemented to solve the problems of farmers, but such policies have been applied nationally, disregarding the problems of farmers in specific areas. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the problems in terms of production and marketing for farmers in the northeastern region, and to connect such problems to the implementation of proposed government policies for the development of the rice economy in this region.

RICE PRODUCTIVITY, VARIETIES, AND THE FARMING SYSTEM

The northeastern Thailand rice cultivation region has a cultivated area of approximately 6.32 million ha, or 61.48% of the cultivated area in the country. There are two types of rice in this region: sticky rice for household consumption and Hom Mali ricefor sale. In 2002–2012, cultivated area in the region increased constantly, along with an increase in cultivated area in the country. It increased from 5.19 million ha in 2002 to 6.32 million ha in 2012, or an increase of approximately 22% over the decade. In particular, the area of Hom Mali rice has tended to increase constantly over more than two decades, showing an increase from 2.23 million ha in 2002 to 3.37 million ha in 2018 (Figure 1). Because of the quality of Hom Mali rice, it commands a dominant position in price and marketing demand. In addition, the rice pledging scheme for cultivating Hom Mali rice is more advantageous than for other rice, which incentivizes farmers to cultivate more.

There are two varieties of Hom Mali rice cultivated in Thailand especially in the northeastern region: KDML105 and RD15. Both cultivars are photosensitive, and the paddy has a straw color; the long-grain, clear brown rice has a tip seed that is slightly curved, glossy, and containing a small germ of good quality. It has a low level of amylose at 12–16%. After cooking the rice will be sticky, soft, and will have a good aroma. This region has proper soil series for Hom Mali rice, which are the Roi-et series, Roi-et loam series, Kula Ronghai series, Tha Tum series, and Nakhon Phanom series. Soil series and climate in this region produce quality Hom Mali rice. Additionally, there is rock salt underground because this area used to be a sea in a primitive era; thus, soil salinity and drought give Hom Mali rice a better smell and cooking quality than Hom Mali rice from the other regions (Srisompun et al., 2014). Most farmers in the northeast mainly cultivate for their household consumption, resulting in the selection of varieties based on long grain, good cooking quality, and fragrance. The RD6 cultivar is popular for sticky rice because it has a good aroma, long grain, and high yield, as well as resistance to diseases and insects. The government also encourages farmers to cultivate wet-season rice on account of high yield and marketing demand, so the cultivated area for RD6 rice is constantly expanding. The currently cultivated area for RD6 is 79.72% of the total sticky rice area in all regions; the RD10 and other RD cultivars make up approximately 2%; and other cultivarss such as Niaw Ubon, Hom Sakon, San-pah-tawng, Gam Pai15, and Hahng Yi 71 total approximately 18% (Srisompun, 2012).

More than 90% of rice cultivation in the northeast is categorized as wet-season rice. Every year, farmers will start preparing soil in April, and cultivation in May–June depends on the duration and amount of rainfall in that year. Dry-season rice is limited because of the lack of water and irrigation. Aging farmers and a labor shortage in the agricultural sector have led to a greater use of broadcast rice fields rather than transplanted rice fields. Soil preparation is commonly done with small four-wheeled tractors rather than by hand, as it saves time. Wet-season rice cultivation does not use chemical sprays, as these may leave residues in products and they are harmful to farmers’ health. Farmers use machine harvesting (combines) rather than harvesting by hand. Most Hom Mali rice is sold for household income, but sticky rice is stored until farmers can ensure that they have enough rice for cultivation next year as well as for household consumption through the year; the remainder is then sold.

KEY PROBLEMS AND CONCERNS

Low productivity and small farm size

Because most of the cultivated areas in the northeast belong to the wet-season rice region, there is no irrigation, and many areas suffer from frequent drought, and the fields are sandy and sandy loam. Thus, farmers will select photosensitive rice varieties that are well resistant to agricultural pests and drought. Therefore, the average yield is lower than in the north and central regions; for example, in the northeast the Hom Mali rice yield is 2,225 kg/ha on average, while the central and southern regions have average Hom Mali rice yields of 3,113 and 2,300 kg/ha, respectively (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2016). Because low rice yield has a direct impact on farmers’ income, and Hom Mali rice is the main cash crop for household income, low margins of production together with small cultivated areas then cause poverty and unstable income. These are the main issues that require policy solutions.

The northeastern region has a rice cultivation area of approximately 6.32 million ha and approximately 2,773,651farming households (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018a). Most of these are small-scale farmers, having a cultivated area of approximately 2.28 ha per household. In principle, large-scale farms will have low unit cost; benefiting from the economy of scale, the average cost per unit of production decreases as the size of the farm increases. These economies can occur because the farmer is able to spread more production over the same level of fixed expenses. Economies of size can also occur when a farm is able to obtain volume discounts for inputs such as seed or fertilizer (Duffy, 2009). However, an analysis of profit over cash costs for rice cultivation in the northeast shows that the small-scale farmer (rice cultivated area < 1.60 ha) has an average production cost that is lower than for the large-scale farmer, even though large production should receive benefits from the economy of scale in production. Another reason is that wet-season rice in the northeast uses less fertilizers and chemical products than in the other regions, as these farmers focus more on household consumption. On the other hand, large-scale farmers need to hire labor for almost all activities, but as a result of labor shortages and aging farmers, this produces high costs (Srisompun et al., 2019a). Hence, technology and small machinery development can reduce the increase of production costs in the large-scale farming model. This should be a proper option for farmers in this region and will be discussed further.

Irrigation system

A shortage of water supply for agricultural activities has been a major problem facing northeastern farmers. This region has a total cultivated area of approximately 10.22 million ha and irrigation systems for 1.14 million ha, or 11% of the region’s cultivated area (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018).Cultivated area for dry-season rice is an indicator for sufficient irrigation. The northeast has an area for dry-season rice of 226,220 ha, or 3.86% of total cultivated area, which is quite low when compared with the north (33.94%) and central (44.99%) regions. Most cultivated areas are located outside of irrigation zones and mainly depend on rainfall; this factor is responsible for lower yield than in other regions, and the government is also concerned about this problem. For the last half century, much attention and funds have been channeled into the development of water resources in northeast Thailand. This drive to develop irrigation infrastructure has been spread across technical scales (large, medium, and small), types of techniques (storage/gravity, run-of-river diversions, pump-irrigation, small-scale tanks), and bureaucratic institutions (Floch and Molle, 2013). The Royal Irrigation Department attempts to increase irrigation zones in the region and has implemented a development project over the 2007–2022 period for a potential irrigation zone. This zone, located in the northeast, covers more than 50% of the irrigation development project zone in Thailand or approximately 3.44 million ha. Project descriptions indicate the construction of large and small reservoirs, a check dam, a floodgate for water retention during cultivation, and construction of an electric pumping station (Knoema, 2017). Prior to 2006, the irrigation zone in the northeast was 521,513 ha; in 2006 this zone increased to 976,389 ha (Lam nam oon Irrigation project, 2006), and in 2017 it increased to 1,139,049 ha (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018). Even though the irrigation zone has been increased more than twice from the past, it still has a low proportion when compared with the other regions. A significant constraint for developing irrigation systems in the northeast is that internal water resources are ill suited for the development scenarios envisioned by planners and decision makers. There is a low runoff-to-rainfall ratio and a mostly flat and undulating topography, which puts considerable limits on surface water storage and gravity diversions (Molle et al., 2009).

Climate change: drought and flooding

As mentioned, most rice cultivation in the northeastern region is done outside irrigation zones and mainly depends on rainfall and climate. Rainfall in each year will affect both quantity and quality of rice in this region. Currently climate variability causes unstable seasons and rain scattered during the year; temperature and rainfall fluctuate as well, and extreme events often occur and are more severe. This region always suffers from drought, which is an important constraint to crop production in northeast Thailand. This region has been frequently subjected to drought as a result of the erratic distribution of rainfall, dry spells in the rainy season, and low water-holding capacity of soils. Thirteen out of 34 years during the period 1970–2004, namely 1972, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1987, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998, and 2004, were drought years in northeastern Thailand (Prapertchop et al., 2007). The mean annual rainfall over the 2001 – 2011 period was 1,462 mm while the mean annual rainfall over the 2011 – 2019 period was 1,348 mm. Furthermore, in the drought year 2012, mean annual rainfall declined 239 to 375 mm, in comparison with mean annual rainfall over the 2001–2011 time periods in the selected site study. Rice is the main crop affected by drought. The yield loss due to drought was about 55–68% of rice cultivated in the study site (Polthanee et al., 2014). According to Gypmantasiri et al. (2003), 19% of northeast Thai farmers experienced drought while growing rice at the planting stage, and 40% of them at the tilling stage, although another 23% reported that drought could affect rice growth at any growing stage. The rice yield reduction caused by drought will become more serious in the future (Prabnakorn et al., 2018).

Other than drought, flooding is another important problem, where farmers in the lowland northeast have suffered in the past decade, as the topography is a basin. The area for growing lowland rice is approximately 528,000ha (Rice Department, 2016). In the past decade, northeastern farmers, especially in low land areas, experienced flooding and damaged rice production five times in a decade: 2010, 2011, 2013, 2017, and 2019. The severity of the damage to rice fields and the effect on farmers depend on flood duration and the size of the affected area. For example, the latest flood in 2019 caused damage to 363,200 ha of rice fields in the northeast, and rice production was lower than estimated by1–1.1 million tons (Prachachat, 2019). Climate variability that damages agricultural products has a direct impact on farmers’ lifestyle, who are sensitive because they have less income and high debt.

Labor shortage and aging farmers

The expansion of industrial and service segments has increased the labor demand for non-agricultural segments, and wages in these segments are higher than agricultural wages. There is therefore a move of labor from agricultural to other segments (OAE, 2016). Moreover, the average age of northeastern farmers increased continuously from 51.3 years old in 1987 to 54.70 years old in 2019 (Butso, 2010; Srisompun et al., 2019a). An increase in the average age of farmers confirms a worry that new generations do not want to be farmers (Patmasiriwat, 2010). Most young people who have grown up in farmer families in Thailand do not want to be farmers. In their perspective, rice farming is a career that involves working hard in the field all day and earning little money. Consequently, farming is not considered as a worthy profession. Furthermore, most farmers believe that being a rice farmer indicates a lower social status. As a result, they attempt to encourage their offsprings away from the farm. Therefore, when their children face career choices, non-agricultural options are highly encouraged by the parents (Tapanapunnitikul and Prasunpangsri, 2014).

Currently, the result is a labor shortage arising from the absorption of labor into the industrial and service segments and the aging farmer issue; these factors push the adoption of agricultural machinery to replace human beings in the entire rice production process (Soni, 2016). Most farmers use small four-wheeled tractors for plowing, instead of the labor of draft animals and hand tractors of the past, robotic chemical spraying machines instead of hand sprayers, and combine harvesters instead of the labor of human beings and draft animals to carry out threshing(Poapongsakorn, 2011; Napasintuwong, 2017). According to Srisompun et al. (2019a), the rice yield, labor usage, labor productivity, and farm revenue of farmers in the northeastern region vary by mechanization level. The high use of rice production machinery has caused a decrease in farmers’ net profit because of the effect of the decreased average yield.

Increase of production costs

Labor shortages in the agricultural sector and the aging of farmers generate high labor wages in this sector. Farmers have to use agricultural machineries instead of human labor in almost all activities of production such as tillage, cultivation, and harvest. And production cost needs to include the increase of fertilizer cost as well. Regarding the seed source, Napasintuwong (2018) indicated that farmers in the region had more than one source of seeds, most of them kept their own seeds for following crops, farmers' groups, cooperatives and Community Rice Center (CRC) were the key sources of seeds in the regions, and public institutes played an important role in providing seeds to farmers. Most of them replaced their seeds within two to three crop years, , and they have to buy new seeds; only a few of them select seeds from their field for further use. These factors lead to high production costs for farmers in this region. Production costs increased from 6.06 Baht/kg in 1987 to 10.49 Baht/kg in 2013(Butso, 2010; Srisompun et al., 2014), or increased more than 73.10% in 28 years, while the average rice yield for this region has changed only slightly. Thus, the average income per household from rice cultivation has decreased.

Price fluctuation

In the past, prices have lightly increased, and farmers have always suffered from price fluctuations, especially northeastern farmers, who grow Hom Mali rice and RD6, which are photosensitive. So this is a key limitation; because of the photosensitivity, rice grows only once a year (in the wet season) and should be harvested during the same year (November–December). Because large amounts of harvested Hom Mali rice enter the market at the same time, the farmers are forced to sell their rice at a low price during the harvest period (Thongngam, 1999). However, because the demand for rice persists throughout the year in Thailand, the price of rice increases after the harvest season and peaks between April and July (Office of Agricultural Economics, 2018). Accordingly, if the farmers store their rice and sell it between April and July, they can earn higher incomes than those earned from selling their rice during the harvest season; consequently, they can achieve maximum profits (Thongnit, 2008). However, most farmers in the northeast choose to sell their rice immediately after harvest, preferring to sell freshly harvested rice instead of storing the rice for later sale (Srisompun et al., 2019a), due to household expenditures and the shortage of agricultural labor (Srisompun et al., 2014).

KEY POLICY IMPLEMENTATIONS

Large-scale farming model

In 2015, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives of Thailand launched the first phase of a newly initiated program called the “large-scale farming model.” This aimed to improve production efficiency and competitiveness by reducing production costs, increasing yields, and aligning production with market demand. The program, however, has experienced several problems that may severely undermine its future prospects, including a lack of well-rounded managers, land fragmentation, poor water management, weak governance, farm debts, enticing benefits in the short run, and equity issues (Duangbootsri, 2018). Large-scale farming has more than 6,000 groups with 405,205 households, and the northeast has 3,016 groups with 233,155 households or more than 50% of large-scale farming in the country (Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, 2019). However, the number of household farming in the northeast has around 3.42 million households, the share of participated farmer is around 6.83% of total farmers in the region. Thirapong (2019) mentioned that significant problems of farming are that farmers in this area are aging and operate at small scale, which encouragement and management for cultivation are difficult. This is an important issue that has a direct impact for large-scale farming. The appropriate option should be improving skills and competences of the leader farmers in the region by introducing a training programme, and enhance the dissemination and transfer of knowledge and innovation is necessary for the project to be successful. Further, relevant officers still misunderstand in terms of promotion of large-scale farming and lack of marketing promotion and information access; in addition, there is redundancy between related government agencies. Besides, rice farming does not have the production structure that allows a scale advantage to take place. As a result, it is unlikely that the program can be sustained in the long run after the government’s subsidy is withdrawn. Policymakers should also be cautious about the impact that the program could have on rural inequality. Specifically, the program may widen the inequality gap in rural areas because it tends to favor large farms while discriminating against small farms (Duangbootsri, 2018).

Flooding and drought support program

In the past decade, northeastern farmers have suffered from natural disasters every year, whether flooding or drought. Government policy has provided continuous support, with an increase in the budget especially during the year that problems spread to many provinces. But government subsidies may not solve this problem in the long run. Other than efforts from governmental agencies or other institutions to solve this long-run problem, other means such as research and development of short-growth rice (RD51) have been implemented. This type of rice has to be harvested prior to flood season. RD51 developed from KDML105; it is resistant to sudden flood, as it can straighten the internode up above water, and it is resistant to floods during the tillering stage (from sowing until 60 days past planting). The cooking quality is similar to KDML105 (BIOTEC, 2013), but its weaknesses are susceptibility to rice blast disease, bacteria leaf blight disease, gall midges, and plant hoppers, and therefore it is not popular. In addition, an integrated assistance project has been implemented for farmers who suffer from drought by encouraging them to grow plants that use less water or to raise animals instead of cultivating dry-season rice where northeastern farmers in an irrigation zone are likely to adapt better than in other regions. Evaluation of this project has found that it is quite delayed, and farmers are not supported for seeds or animals; this does not meet their requirements, as it is a national large project and implemented at the department level. Such projects should be implemented at the provincial level rather than the central level in order to avoid the delay, and farmers may then adapt as appropriate by choosing to cultivate a rotation crop or raise animals (Chaowagul et al., 2016).

Crop rotation

More than 80% of the northeastern area depends on rainfall. There the crop product has low efficiency because the area is improperly used and is constrained by resources and the environment. Farmers have few production options and a lack of diversity, which leads to low income, lack of stability in an agricultural career, lack of strength in the community, and poor quality of life. In addition, the production structure depends on a few main crops; these are mostly rice, cassava, and maize. If any year has a low yield, this will have a great impact on farmers’ income. Growing post-harvest crops such as through a rotation of rice–peanut, rice–cassava, or rice–corn will provide higher yield than growing rice in a mono crop system (Boonpradub et al., 2016). The objective is not only to raise income for farmers and reduce the dependence on rice cultivation, but also to reduce plant disease and improve soil quality in rice fields by growing crops in rotation. The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives always encourages farmers in this region to grow crops in rotation post-harvest, for example by encouraging farmers to grow forage plants, plants that use less water, or to adopt integrated farming by arranging crops to suit each local area, which can increase production efficiency. The significant issue for this policy is that farmers are unable to select crops or animals, as it has been specified from the central sector regardless of farmers’ actual desires. Further, their products have few buyers and there is no local market support. Therefore, farmers must sell their products at a lower price than actual production cost (Chaowakul et al., 2016). Greater marketing familiarity for farmers is important, and this should be a part of the project to promote crop rotation. Events for farmers to meet agricultural product representatives or buyers should be set up prior to planting season in order to exchange information between farmers and prospective buyers; this will provide farmers with more knowledge on agricultural marketing.

Community Rice Center (CRC)

The Community Rice Center is a farmer organization by which the Rice Department and the Department of Agriculture Extension cooperate to enhance the development of rice production. The major aim is the production and distribution of quality rice seed in the community; the quality seed should be met with the minimum standards of Plant Varieties Act or seed law. In addition, it is a center to transfer rice production technology by focusing on farmers’ knowledge and the ability to improve themselves to be self-reliant. This center has operated since 2000 under the Department of Agriculture Extension, and since 2006 it has been operated by the Rice Department. In 2019 there were 1,786 Community Rice Centers registered with the Rice Department. These centers are located in many major production areas in the country, and they provide farmers with good quality rice seeds in the amount of approximately 100,000 tons per year (Rice Department, 2019). Promotion policies of Community Rice Centers in the northeastern region not only increase the quality of rice seeds but also increase farmer income from rice seed production.

Rice pledging scheme

The rice barn pledging scheme aims to prevent the release of quantities to the market that are in excess of demand, thereby maintaining stability and raising prices. This scheme gives farmers the choice to store their rice and improve their paddy quality, to yield a higher price. The barn-pledging scheme began with the 2014/15 crop year. The farmer could bring Hom Mali and sticky paddy to apply for a loan from the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC) for 90% of the market price. The credit limit could not exceed 300,000 baht without interest, and there was an additional 1,000 baht per ton for farmers who stored rice in their barn more than 30 days as a motivation to delay disposing of rice on the market during the harvest season. Farmers had to repay their loans within 4 months of receipt. The scheme has operated continuously until the present. To increase the motivation to participate in the scheme, the paddy storage fee was raised to 1,500 baht per ton for participating farmers in production year 2017/18, but participation is still lower than targeted (target production is 2 million tons), results in a high proportion of the total rice product being released to the market (Srisompun et al., 2020). Most of the northeastern farmers who participate in this project are large-scale farmers with cultivated area of more than 4.8 ha. The small-scale farmers have to kept their rice product for home consumption, so they have not enough paddy for participating in the rice-pledging scheme . This scheme is of benefit mostly for large-scale farmers, but small-scale farmers should have other options.

FUTURE OUTLOOK

There are several problems with policy implementation to assist northeastern farmers. This study has produced some recommendations for policy improvement:

CONCLUSIONS

The northeastern region of Thailand is a significant area for quality rice cultivation. Rice is not only the main household income for small-scale farmers, but it also is important as the staple food for this region’s population. Yet constraints in the form of irrigation, topography, climate variability, and labor present continuous and long-term problems. These include low yield and productivity, high production costs, price fluctuation, and poverty. While the government has policy measures to assist farmers, many policies do not provide benefit for farmers in this region who are poor and have limited access to utilities. The growth of urban population centers has left farmers in this region operating at small scale and with limited cultivated area. Therefore, policy options should include support for labor-saving machinery to small-scale farmers and the development of knowledge both in production and marketing. Such knowledge should include the benefit of technology for farmers, by focusing on production that reduces cost such as through small agricultural machinery and production of quality rice seed. Development for small-scale farmers is necessary, as this group receives fewer benefits than large-scale farmers. If production promotion is offered for quality rice or organic rice, healthy rice, and local rice, this could add value to production in limited areas. Further, the government should focus on value-added rice in the northeastern region by developing varieties of local rice and Hom Mali rice to suit each local area, as well as colored rice and healthy rice. The genetic diversity of rice in the region could be of great advantage to local farmers.

REFERENCES

BIOTEC. 2013. New Variety of Rice Resistant to Sudden Flood “RD51” Certified Variety from Rice Department. (http://www.biotec.or.th/th/index.php.; Accessed 15 February 2020). (In Thai)

Boonpradub, S., C. Cheangauksorn, P. Muangphet, P. Phangchun, B. Phanpeng, S. Jaichit, P. Peabying, and S. Chuthammathat. 2016. Research and Development on Sustainable Cropping Systems in Rainfed Area http://www.doa.go.th/research/attachment.php?aid=2270. (In Thai)

Butso, O. 2010. Efficiency change and resource use in Thailand Rice Production: Evidence form Panel Data Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Kasetsart University, Thailand.

Chaowagul, M., S. Rungsipathra, O. Sirisomphan, and C. Choesawan. 2016. Final report “The Adaptation to drought of rice farmers in irrigated areas with evaluation on integrated mitigation project to farmers affected by drought project”. Thailand Research Fund. (In Thai)

Chinese Consulate. 2019. Northeastern Thailand: Brief introduction. (http://khonkaen.china-consulate.org/eng/lqgk/.; Accessed 15 February 2020).

Duangbootsri, U. 2018. Thailand’s Large-Scale Farming Model: Problems and Concerns. Agricultural Policy Platform. (http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=932: Accessed 15 February 2020).

Duffy, M. 2009. Economies of Size in Production Agriculture. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 4(3-4): 375–392. doi: 10.1080/19320240903321292.

Floch, P. and F. Molle. 2013. Irrigated Agriculture and Rural Change in Northeast Thailand Irrigated Agriculture and Rural Change in Northeast Thailand: Reflections on Present Developments. In book: Governing the Mekong: Engaging in the politics of knowledge (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283720675_Irrigated_Agriculture_and_Rural_Change_in_Northeast_Thailand_Irrigated_Agriculture_and_Rural_Change_in_Northeast_Thailand_Reflections_on_Present_Developments; Accessed 25 February 2020).

Fund-Isaan. 2019. Why Isaan. (https://fund-isaan.org/content/why-isaan; Accessed 15 February 2020).

Gecko Villa Thailand. 2019. General Background Information and Specific Details on Northeast Thailand. (https://www.geckovilla.com/thailandfacts.html.; Accessed 12 February 2020).

Gypmantasiri, P., B. Limirankul, and C. Muangsuk. 2003. Bio-physical and Socio-economic Characterization of Rainfed Lowland Rice Production Systems of the North and Northeast of Thailand.(http://www/mecweb.agri.cmu.ac.th/agsnst/publication;Accessed 28 February 2020).

Keyes, C. F. 1967. Isan: Regionalism in Northeastern Thailand. Cornell Thailand Project; Interim Reports Series, No. 10 (PDF). Ithaca: Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University.(https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/57533/065.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.; Accessed 12 February 2020).