ABSTRACT

The demographic changes in Thai agricultural sector have raised concerns over the lower participation of young agri-entrepreneurs and the sustainability of the sector. Oppositely, the digital economy has, however, widened the opportunities for younger generations in various ways. This leads to the emerging and developing of seven models of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs, from farm improvement, farm services, farm diversification, processing-driven, market-driven, service-driven, and co-operative models. The differences in these successful models show the diversity in conditions and strategies of younger generations’ entrepreneurship. Among these seven models, five main comparative advantages of Thai young agr-entrepreneurs have been identified; namely access to information and technologies, design thinking process and creativity, communication skills, agribusiness management skills, and networking skills. However, if Thailand would like to promote young entrepreneurship on a wider scale, there are certain limitations that need to be addressed. This includes access to land, technology advancement, market channels and places, and the financial support mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

The demographic structural change in Thailand towards an aging society is now obvious. This trend is more serious for the Thai agricultural sector with less participation of younger generations in farming and other related activities. This concern has been raised by several public and private organizations followed by their initiatives and supportive projects/programs in enhancing more active participation of young agri-entrepreneurship in Thai the farming sector. At the same time, upcoming trend in digital economy, both e-commerce and social media, allows young entrepreneurs to present their creativities and passions in their own ways, leading to inspiration for other young generation.

This paper aims to present and analyze the experiences of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs. First, it will start by providing background information of Thai agricultural sector, especially the demographic changes in this sector. Then, the promotion of young agri-entrepreneurs by several organizations will be reviewed. Third, seven models of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs will be analyzed, in order to understand the conditions and strategies of each model. This will, later, lead to understand the comparative advantage of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs. On the opposite, the main limitations of young agri-entrepreneurs will also be analyzed in order to suggest for policy recommendation in the final sections.

Thai agricultural sectors and young agri-entrepreneurs

In the 2013 agricultural census, the Thai agricultural sector has 5.9 million households, with 19.68 million members and 10.69 land plots. On average, each farm household has 2.7 members, of which 75% of members have participated in farming activities (Attavanich et al, 2018).

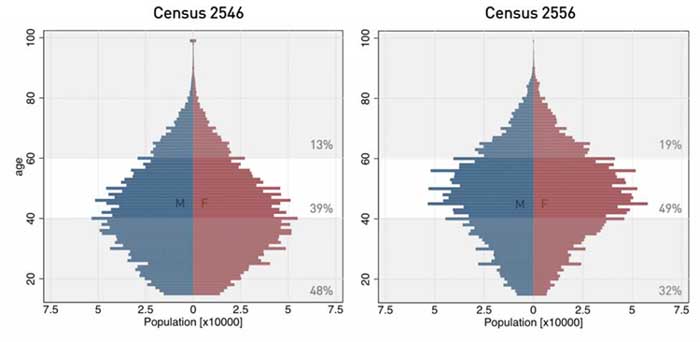

In terms of age structure, Fig. 1 shows the change of Pyramid Population structure between 2003 and 2013, with higher proportion of aging farm members. In general, Thai agricultural sector has moved to aging society, even faster than the national population structure. While the proportion of population with 15-40 years old at the national level is 51%, the same proportion for agricultural sector is only 32%. On the opposite, while the proportion of aging members at the national level is 14%, for the agricultural sector is 19% (PUIER, 2018).

Fig. 1. The Population Structure of Thai Farm Households’ members in 2003 and 2013

Source PUIER, 2018.

In terms of land holding, the average number of land holding in Thailand in 2017 is 14.3 rais (or 2.89 hectares). More than 50% of Thai farmers have the land holding of less than 10 rais (or 1.6 rais) and 80% of Thai farmers have land holding less than 20 rais (or 3.2 hectares). Comparison between 2007 and 2017 clearly shows the reduction of farm size in all groups. The large farm, with more than 40 rais (or 6.4 hectares), which are normally found in the central plain and the lower northern region for rice, sugarcane, maize, and cassava production, and some provinces in the south for rubber. Only 59.8% of Thai farmer households have legally land entitlement, and only 42% can access to water resources all year round (Attavanich et al, 2018).

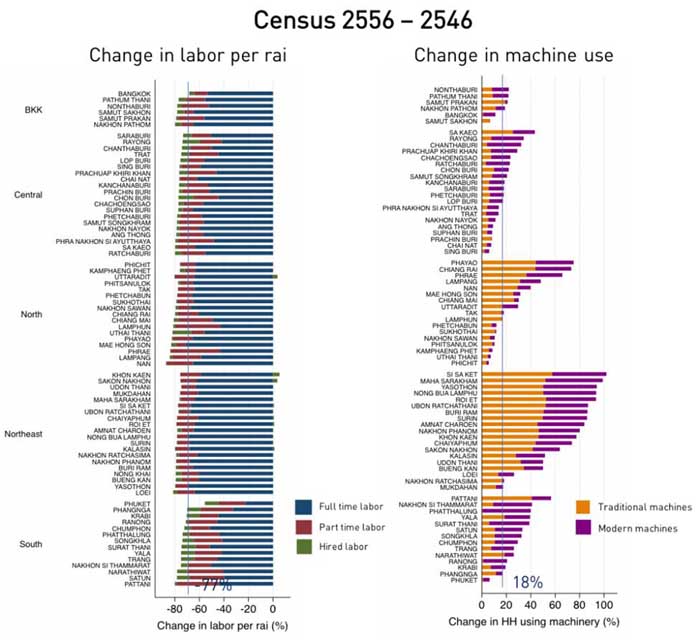

In terms of labor, Thai farm households use on average of 0.51 person/rai of farm production. This average farm labor used has been dropped in all regions, between 2003 and 2013. On the opposite, the uses of farm machinery have been increased in all regions, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Changes in Farm Labors and Machinery Used in Thailand between 2003 and 2013.

Source: PUIER, 2018.

In terms of educational background, members of Thai agricultural sector have improved in all age groups. The proportion of members who are high school graduates has been increased from 12.1% in 2003 to 21.5% in 2013. This will lead to better opportunities for young agri-entrepreneurs, which will be discussed later.

In terms of income, average income per capita of Thai farm households is 57,032 THB in 2017, which around two-third (66%) of this income comes from agricultural sector. However, in 2017, 40% of farm households in Thailand has income lower than national poverty line, with 32,000 THB/person/year. Moreover, 30% of Thai farmers have debt higher than annual income. On average, the debt to annual income ratio is 1.3 times, which 69% of debts come from agricultural purposes (Attavanich et al, 2018).

The promotion of young agri-entrepreneurs in the Thai farming sector

To counter the trend of lower participation of young members in the Thai farming sectors, several public and private organizations in Thailand have the promotion policy, programs, and projects for supporting new young farmers. For example, the New Farmer Development Project, run by Agricultural Land Reform started in 2009, has provided short courses training for more than 30,000 new farmers each year. Smart farmer Smart Officer by the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives provide the deliberative consultancies for young farmers. The large agribusiness organizations, like CP and Kubota, also introduce the projects to boarder farming perspective university students and children, namely Kubota Smart Farmer Project and CP’s Rice Farm Learning for children. University, like Kasetsart University, also run the course on My Little Farm Project to inspire and support young farmers as well (Tapanapunnititkul, 2014).

One of the large nationwide programs is the young smart farmers projects, operated by the Department of Agricultural Extension, with 7,958 young smart farmers from around one million smart farmers all over the country in 2013-2017, and the target of additional 6,450 young smart farmers in 2018. DOAE has also set up the further target of reaching 24,000 young farmers in the new four years period during 2018-2021. From this 24,000 young smart farmers, 1,800 of them will be aimed to develop to be young smart enterprises, with the whole value chain management from farming up to processing and marketing. Moreover, DOAE aims to establish 258 networks of young smart farmers to be an innovation and incubation hub for young smart farmers in each provincial and local area (DOAE, 2018).

In terms of effectiveness, Cochetel and Pibul (2018) found that for young farmers joining the young farmers supporting projects (or programs), they have gained the support for technical farm practices most, followed by network building, and, then, access to finance, to market, and to land accordingly. Cochetel and Pibul (2018) also asserted that the support for young generation of farmers required understanding in diversity of different farm activities and business models.

To compare between ordinary farmers and smart farmers, the Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart Univeristy, showed that 29% of smart farmers used computer and internet, while only 17.7% of ordinary farmers use computer and internet. In searching for relating farm information, 18.4% of smart farmers used smart phones, compared to 8.9% of ordinary farmers. Net farm income for smart farmers is on average of 257,213 THB/year, compared to 136,874 THB/year for ordinary farmers. Smart farmers also had higher net household income (146,307 THB/year) than ordinary farmers (59,626 THB/year) as well. In short, the promotion of smart farmers, including young smart farmers, can promote the better income for Thai farmers (Matichon, 2016).

THE MODELS OF YOUNG AGRI-ENTREPRENEURS IN THAI FARMING SECTON

In running their farm businesses, there are several business models as shown in Cochetel and Pibul (2018). Based on value chain’s activities from several sources, we can identify 7 business models commonly found in Thai farming sector now.

- Farm improvement model; In this model, young farmers play key roles in providing and developing farming techniques, such as single rice intensification, smart farming applications, farm machinery etc., for their farms. In this model, the succession of farm business does not necessary required. In many cases, their parents keep running their farms, with deliberatively technical supports from young farmers. One of the most well-known networks in this model is “Holiday Farmers Network”, which support hundreds of young farmers to work in their other business during the week days and run their farm together with their parent during the weekend. The success of this network comes from the impressive improvement in rice yield, lower average cost (per ton), and also more convenient practices for elderly farmers, in other words, their parents.

- Farm services model; In this model, young agri-entrepreneurs use their own specialization in some certain crops and/or activities in establishing and running their farm service businesses. During the high rice price period in 2011-2013, these farm services businesses had been developed in various forms, especially in land preparation and rice harvesting phase. Fruit and vegetable productions also require these special farm service teams (or enterprises). With on-going labor shortage in Thailand and rapid technological advancement, this farm service model will find more opportunity to grow. However, with high investment costs for farm machinery, the access to capital can be one of main barriers for the new comers in this model.

- Farm diversification model; In this model, some forms of succession (or acquisition) of farm businesses are required, because young farmers decide to change farming system and production structures. In Thailand, young farmers would like to shift from traditional cash crops, like rice, cassava, rubbers, into higher values crops, especially vegetables and fruits. Due to the limitation of investment capital and farming experiences, the succession (or acquisition) of farm businesses normally occurs step-by-step, depending on the success of their new farm investments. The development of this model normally also goes hand in hand with other models, for example market-driven and service driven models.

- Processing model; In this model, young entrepreneurs focus mainly, or solely, in processing business, while their parents keep running their farming businesses. There are hundreds of successful cases, from dried banana to fried fish, from rice snacks to herbal cosmetics. The economic opportunities of this model are based on (a) the higher growth in processed food consumption, (b) the rapid advancement in smaller-scale food processing machinery (therefore require much lower initial investment and also break-even points) and (c) the expansion of online marketing and social media. Moreover, the Thai government also support this model development by (a) providing soft loans for young entrepreneurs (b) organizing marketing events in several cities and towns and (c) technical recommendations for export.

- Market-driven model; In this model, young entrepreneurs take responsibility mainly or solely in the marketing aspect. By applying more online marketing and social media, this model fits well with their internet skills and life-styles. In this model, they do not require farm succession, and in some cases, not even require to quit their permanent jobs (at least at the beginning period). However, involvement in marketing activities requires young entrepreneurs to understand, take care, and, in some cases, improve their parents’ farming (and/or processing) practices as well. Some obvious successful cases are the “Hundred Million Blue Crab” and “Folk rice”, which both cases base their business mainly on-line.

- Service-driven model; Thank to the fast growing of Thailand’s tourist and hospitality industries, there are huge opportunities for young farmers (or entrepreneurs) to start or expand their business (or their parents’ businesses) into service sectors, including agro-tourism and farm stay, café and restaurants, co-working space, and learning activities. Apart from high value business, the service sector also allows them to present their passions, use their skills, and experiment their creativity. Therefore, service-driven model is also quite feasible for young generation to step in running farming businesses in Thailand. There are several successful cases in terms of agro-tourism, farm stay, and café and restaurants.

- Co-operative model; Unlike other previous models, young agri-entrepreneurs in this model do not only run their own farm businesses, but also take care of co-operatives and/or community-based enterprises. In several cases, co-operative and community-based enterprises are necessary in order to reach their economies of scale and, in some cases, economy of scope as well. The Folk Fisherman Shop is one of the example of this model, running by younger generation entrepreneurs. In this model, the collective management skills, such as trust building, transparency process, negotiation skills are highly essentials. In general, due to its complication, this model is not quite popular, though, it may be necessary for some certain cases.

These seven models of young agri-entrepreneurs are quite different in terms of management skills and farm connection as summarized in the following Table.

Table Main characteristics of seven young agri-entrepreneurs models.

Source: Own observation

THE COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE OF YOUNG ENTREPRENEURS

Comparatively, young entrepreneurs in farming and related sectors show their advantages in various ways, which can also contribute to the improvement of Thai farming and agribusiness sectors as a whole. At least, there are five main advantages needed to be discussed here.

- Access to information and technologies; Due to information technology and better education background, young agri-entrepreneurs are keen in searching, testing, and applying new technologies. This advantage is quite essential in the period of higher competition and rapid technological advancements. The application of smart farming techniques, i.e. precise agricultural tools, by Thai young entrepreneurs is one of the most obvious examples of this advantage.

- Design thinking process and creativity; Running agri-businesses today requires more impressive customers’ experiences both in terms of products and services. Therefore, creative designing their products and services become more crucial. Fortunately, Thai young agri-entrepreneurs have better skill and experiences in design thinking process, which allow them to improve their product characteristics and service qualities. Moreover, this successful design cases also provide good inspiration for other young entrepreneurs, especially newer generation.

- Communication skills; Since new generation entrepreneurs have grown in borderless and worldwide-web environments, therefore, they are growing with wider communication practices, both in terms of languages, styles, and channels. These communication skills are very helpful in expanding their markets, domestically and internationally. They can certainly also help other farmers in promoting farm products as well. Especially, during the period of low rice price in 2016, the communication skills of young agri-entrepreneurs played key roles in finding alternative marketing channels for Thai rice farmers in boarder scale.

- Agribusiness management skills; With better education background and available information and applications, new agri-entrepreneurs are generally better in several essential agribusiness management skills; for example, accounting, logistic management, planning. These better skills do not only benefit their farm or agribusiness performances but also facilitate them in searching for new opportunities including their investment mobilization. Moreover, these skills are also hopefully help them in risk management in higher uncertain business conditions.

- Networking skill; Young agri-entrepreneurs have more interesting and better skills in networking. Thanks to the digital era and social media, they can run their networks across the local areas, searching for several important signals, from farm surveillances to marketing opportunities, and at the same time, building stronger relationship. Unsurpsingly, PUIER (2018) found that, with 35% of farmers who are participating in the network, the Network of New Generation Farmers becomes the most active network in Thai farming sector now. Certainly, this advantage can further apply for developing Thai farming sector more in the longer term.

THE LIMITATION OF YOUNG AGRI-ENTREPRENEURS

On the opposite, Thai young agri-entrepreneurs also face several serious limitations, which can block or turn down their business opportunities and performances. There are four main limitations needed to be addressed here, if we would like to continually promote young agri-entrepreneurship in Thai agricultural sectors.

- Access to land; Access to land is the most important barrier for Thai young agri-entrepreneurs, due to high land price and concentrate land holding structure. Without access to adequate land holding, their agribusiness plan can be blocked or delayed. Unfortunately, there are no specific government policy in solving this problem (Faysse and Pibil, 2018). Therefore, most of young agri-entrepreneurs in Thailand, especially in farming sector, are the successors of their parents’ farms.

- Labor shortage; Although young agri-entrepreneurs may be keen in management skills, many of them are not familiar with several labor intensive farming practices. Moreover, the labor shortage in farming sector becomes more usual in Thailand right now. This limitation can prevent young agri-entrepreneurs in investing in some labor intensive crops and/or activities. There are three key points to counteract this limitation; namely (a) farm machineries and smart farm applications development, (b) developing new business model in order to have more secure co-operation with other farmers and/or farm service businesses, and (c) adjust their farm patterns and structures to fit with available farm labors.

- Access to market channels and places; Although online market is expanding, in practice the traditional market channels are still much more important channels in Thailand, especially for the provincial markets. Thus, access to market channels and places is still important for the growth of young agri-entrepreneurs. Unfortunately, in general, the marketing channels in Thai agribusiness have been concentrated into the control of few large modern trade and agribusiness firms. At the same time, access to good market places are quite expensive, leading to higher costs and higher risks for new comers in agribusiness. Apart from fast growing online market and government public events, there are no obvious policy solutions to this limitation.

- Financial support mechanisms; As shown above, young agri-entrepreneurs’ models in Thailand are highly diversified. Although Thai governmental financial institutions try to provide several financial supports for new enterprises, their financial supports still mainly based on traditional farming, processing, and trading sectors. Thus, for young agri-entrepreneurs running business models on farm services, online marketing, service-driven business may find some difficulties in accessing to finance, especially in the beginning when their chances of success are still unclear. Hopefully, with experience sharing, the development of new financial mechanisms and products will be sooner developed to support young agri-entrepreneurs in all models.

Policy Recommendations for Young Agri-entrepreneurship Promotion

In general, the future of Thai young agri-entrepreneurship is quite positive. Thank to large and diverse farming sectors, online marketing expansion, fast growing tourist sector, and strong food culture, the opportunities for young agri-entrepreneurs are certainly open. Above all, within these preferable business environments mentioned earlier, the inspiration and passions in running their agri-enterprises are perhaps the most important factors.

However, although Thailand has been well recognized as top farms and food products in the world market, the perceptions towards farmers are normally opposite. Thai farmers, and also the whole farming sector, are perceived as poorer and lower status in the society, which, then affects the perceptions of young generation, including farmers’ kids. Thus, this perception can be one of the most important barriers for new-coming young agri-entrepreneurs.

Therefore, public perception to farmers and farming is quite crucial for the promotion of young agri-entrepreneurs in the future. In fact, this public perception can also be changed through the on-going introduction of successful experiences and impressive innovations of these agri-entrepreneurs.

Apart from public perception, these four main limitations must be addressed appropriately at policy levels. These policy proposals should be analyzed and discussed soon in order to promote more young agri-entrepreneurship in this country;

- Land redistribution policy; As mentioned earlier, access to land is the most important barrier for young agri-entrepreneurs. Therefore, series of land redistribution policies, including progressive land tax, the establishment of land bank, deliberative spatial planning, may be required.

- Technology advancement; Although the technological advancement will certainly be continued, the crucial point is the progress rate of this advancement in countering other limitations, especially the labor shortage. Instead of mainly searching for new emerging technologies, the incubation for new advancement has been highly suggested.

- Attractive market channels and spaces; Apart from online marketing, other marketing channels and spaces is still concentrated and, therefore, difficult to access. Thus, it is essential to develop and provide market channels and spaces for young generations in various ways. The design of public and private spaces can be useful for new comers. At the same time, developing alternative business models in both existing and new marketing channels, including social enterprises, is highly recommended.

- Financial mechanism development; the development of various well-design financial mechanisms and/or supports will certainly unlock the financial limitations for young agri-entrepreneurs. However, this development requires deep understanding of diversity of young agri-entrepreneurs’ models and, consequently, the customization in financial mechanism design. The stronger policy signals from Thai government may stimulate this process.

REFERENCES

Attavanich, W., S. Chantarat and B. Sa-ngimnet, 2018. Microscopic view of Thailand’s Cochetel and Pibul (2018)agriculture through the lens of farmer registration and census data. Forthcoming PIER Discussion Paper.

Cochetel, C. and Pibul, K, 2018. Diversity of Young Generation Farmers in Chiang Mai and Prachin Buri; Characteristics, Challenges, and Participation in Farmer Supporting Project.

Department of Agricultural Extension, 2018. The Policy of Smart Farmers Development. DOAE, Bangkok, Thailand. (in Thai).

Faysse,e N. and Pibul, K., 2018. The Policy Supports for Young Generation Farmers: The Review for International Studies and Thailand.

Matichon, 2016. Shock!! Thai Farmers are still in 2.14: OAE allow Kasetsart University to Analyze Deep Information for Agricultural Plan Restructuring. https://www.matichon.co.th/economy/news_291897 (in Thai)

National Economic and Social Development Board Office, 2017. New Generation Farmers for the Future of Thailand. The Public Seminar on Mobilizing the 12th National 5-years Plan for Future of Thailand. NESDB, Thailand (in Thai).

Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research (PUIER), 2018. Microscopic view of Thailand’s agriculture through the lens of farmer registration and census data, PUIER, Bangkok Thailand, (in Thai).

Tapanapunnititkul, Onanong, 2014. Entry of Young Generation into Farming in Thailand. FFTC-RDA International Seminar on Enhancing Entry of Young Generation into Farming in Thailand, October 20-24, Jeonju, Korea.. http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=330.

|

Date submitted: Oct. 1, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Oct. 24, 2018

|

Youth and Agri-Entrepreneurship in Thailand

ABSTRACT

The demographic changes in Thai agricultural sector have raised concerns over the lower participation of young agri-entrepreneurs and the sustainability of the sector. Oppositely, the digital economy has, however, widened the opportunities for younger generations in various ways. This leads to the emerging and developing of seven models of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs, from farm improvement, farm services, farm diversification, processing-driven, market-driven, service-driven, and co-operative models. The differences in these successful models show the diversity in conditions and strategies of younger generations’ entrepreneurship. Among these seven models, five main comparative advantages of Thai young agr-entrepreneurs have been identified; namely access to information and technologies, design thinking process and creativity, communication skills, agribusiness management skills, and networking skills. However, if Thailand would like to promote young entrepreneurship on a wider scale, there are certain limitations that need to be addressed. This includes access to land, technology advancement, market channels and places, and the financial support mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

The demographic structural change in Thailand towards an aging society is now obvious. This trend is more serious for the Thai agricultural sector with less participation of younger generations in farming and other related activities. This concern has been raised by several public and private organizations followed by their initiatives and supportive projects/programs in enhancing more active participation of young agri-entrepreneurship in Thai the farming sector. At the same time, upcoming trend in digital economy, both e-commerce and social media, allows young entrepreneurs to present their creativities and passions in their own ways, leading to inspiration for other young generation.

This paper aims to present and analyze the experiences of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs. First, it will start by providing background information of Thai agricultural sector, especially the demographic changes in this sector. Then, the promotion of young agri-entrepreneurs by several organizations will be reviewed. Third, seven models of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs will be analyzed, in order to understand the conditions and strategies of each model. This will, later, lead to understand the comparative advantage of Thai young agri-entrepreneurs. On the opposite, the main limitations of young agri-entrepreneurs will also be analyzed in order to suggest for policy recommendation in the final sections.

Thai agricultural sectors and young agri-entrepreneurs

In the 2013 agricultural census, the Thai agricultural sector has 5.9 million households, with 19.68 million members and 10.69 land plots. On average, each farm household has 2.7 members, of which 75% of members have participated in farming activities (Attavanich et al, 2018).

In terms of age structure, Fig. 1 shows the change of Pyramid Population structure between 2003 and 2013, with higher proportion of aging farm members. In general, Thai agricultural sector has moved to aging society, even faster than the national population structure. While the proportion of population with 15-40 years old at the national level is 51%, the same proportion for agricultural sector is only 32%. On the opposite, while the proportion of aging members at the national level is 14%, for the agricultural sector is 19% (PUIER, 2018).

Fig. 1. The Population Structure of Thai Farm Households’ members in 2003 and 2013

Source PUIER, 2018.

In terms of land holding, the average number of land holding in Thailand in 2017 is 14.3 rais (or 2.89 hectares). More than 50% of Thai farmers have the land holding of less than 10 rais (or 1.6 rais) and 80% of Thai farmers have land holding less than 20 rais (or 3.2 hectares). Comparison between 2007 and 2017 clearly shows the reduction of farm size in all groups. The large farm, with more than 40 rais (or 6.4 hectares), which are normally found in the central plain and the lower northern region for rice, sugarcane, maize, and cassava production, and some provinces in the south for rubber. Only 59.8% of Thai farmer households have legally land entitlement, and only 42% can access to water resources all year round (Attavanich et al, 2018).

In terms of labor, Thai farm households use on average of 0.51 person/rai of farm production. This average farm labor used has been dropped in all regions, between 2003 and 2013. On the opposite, the uses of farm machinery have been increased in all regions, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The Changes in Farm Labors and Machinery Used in Thailand between 2003 and 2013.

Source: PUIER, 2018.

In terms of educational background, members of Thai agricultural sector have improved in all age groups. The proportion of members who are high school graduates has been increased from 12.1% in 2003 to 21.5% in 2013. This will lead to better opportunities for young agri-entrepreneurs, which will be discussed later.

In terms of income, average income per capita of Thai farm households is 57,032 THB in 2017, which around two-third (66%) of this income comes from agricultural sector. However, in 2017, 40% of farm households in Thailand has income lower than national poverty line, with 32,000 THB/person/year. Moreover, 30% of Thai farmers have debt higher than annual income. On average, the debt to annual income ratio is 1.3 times, which 69% of debts come from agricultural purposes (Attavanich et al, 2018).

The promotion of young agri-entrepreneurs in the Thai farming sector

To counter the trend of lower participation of young members in the Thai farming sectors, several public and private organizations in Thailand have the promotion policy, programs, and projects for supporting new young farmers. For example, the New Farmer Development Project, run by Agricultural Land Reform started in 2009, has provided short courses training for more than 30,000 new farmers each year. Smart farmer Smart Officer by the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives provide the deliberative consultancies for young farmers. The large agribusiness organizations, like CP and Kubota, also introduce the projects to boarder farming perspective university students and children, namely Kubota Smart Farmer Project and CP’s Rice Farm Learning for children. University, like Kasetsart University, also run the course on My Little Farm Project to inspire and support young farmers as well (Tapanapunnititkul, 2014).

One of the large nationwide programs is the young smart farmers projects, operated by the Department of Agricultural Extension, with 7,958 young smart farmers from around one million smart farmers all over the country in 2013-2017, and the target of additional 6,450 young smart farmers in 2018. DOAE has also set up the further target of reaching 24,000 young farmers in the new four years period during 2018-2021. From this 24,000 young smart farmers, 1,800 of them will be aimed to develop to be young smart enterprises, with the whole value chain management from farming up to processing and marketing. Moreover, DOAE aims to establish 258 networks of young smart farmers to be an innovation and incubation hub for young smart farmers in each provincial and local area (DOAE, 2018).

In terms of effectiveness, Cochetel and Pibul (2018) found that for young farmers joining the young farmers supporting projects (or programs), they have gained the support for technical farm practices most, followed by network building, and, then, access to finance, to market, and to land accordingly. Cochetel and Pibul (2018) also asserted that the support for young generation of farmers required understanding in diversity of different farm activities and business models.

To compare between ordinary farmers and smart farmers, the Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart Univeristy, showed that 29% of smart farmers used computer and internet, while only 17.7% of ordinary farmers use computer and internet. In searching for relating farm information, 18.4% of smart farmers used smart phones, compared to 8.9% of ordinary farmers. Net farm income for smart farmers is on average of 257,213 THB/year, compared to 136,874 THB/year for ordinary farmers. Smart farmers also had higher net household income (146,307 THB/year) than ordinary farmers (59,626 THB/year) as well. In short, the promotion of smart farmers, including young smart farmers, can promote the better income for Thai farmers (Matichon, 2016).

THE MODELS OF YOUNG AGRI-ENTREPRENEURS IN THAI FARMING SECTON

In running their farm businesses, there are several business models as shown in Cochetel and Pibul (2018). Based on value chain’s activities from several sources, we can identify 7 business models commonly found in Thai farming sector now.

These seven models of young agri-entrepreneurs are quite different in terms of management skills and farm connection as summarized in the following Table.

Table Main characteristics of seven young agri-entrepreneurs models.

Source: Own observation

THE COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE OF YOUNG ENTREPRENEURS

Comparatively, young entrepreneurs in farming and related sectors show their advantages in various ways, which can also contribute to the improvement of Thai farming and agribusiness sectors as a whole. At least, there are five main advantages needed to be discussed here.

THE LIMITATION OF YOUNG AGRI-ENTREPRENEURS

On the opposite, Thai young agri-entrepreneurs also face several serious limitations, which can block or turn down their business opportunities and performances. There are four main limitations needed to be addressed here, if we would like to continually promote young agri-entrepreneurship in Thai agricultural sectors.

Policy Recommendations for Young Agri-entrepreneurship Promotion

In general, the future of Thai young agri-entrepreneurship is quite positive. Thank to large and diverse farming sectors, online marketing expansion, fast growing tourist sector, and strong food culture, the opportunities for young agri-entrepreneurs are certainly open. Above all, within these preferable business environments mentioned earlier, the inspiration and passions in running their agri-enterprises are perhaps the most important factors.

However, although Thailand has been well recognized as top farms and food products in the world market, the perceptions towards farmers are normally opposite. Thai farmers, and also the whole farming sector, are perceived as poorer and lower status in the society, which, then affects the perceptions of young generation, including farmers’ kids. Thus, this perception can be one of the most important barriers for new-coming young agri-entrepreneurs.

Therefore, public perception to farmers and farming is quite crucial for the promotion of young agri-entrepreneurs in the future. In fact, this public perception can also be changed through the on-going introduction of successful experiences and impressive innovations of these agri-entrepreneurs.

Apart from public perception, these four main limitations must be addressed appropriately at policy levels. These policy proposals should be analyzed and discussed soon in order to promote more young agri-entrepreneurship in this country;

REFERENCES

Attavanich, W., S. Chantarat and B. Sa-ngimnet, 2018. Microscopic view of Thailand’s Cochetel and Pibul (2018)agriculture through the lens of farmer registration and census data. Forthcoming PIER Discussion Paper.

Cochetel, C. and Pibul, K, 2018. Diversity of Young Generation Farmers in Chiang Mai and Prachin Buri; Characteristics, Challenges, and Participation in Farmer Supporting Project.

Department of Agricultural Extension, 2018. The Policy of Smart Farmers Development. DOAE, Bangkok, Thailand. (in Thai).

Faysse,e N. and Pibul, K., 2018. The Policy Supports for Young Generation Farmers: The Review for International Studies and Thailand.

Matichon, 2016. Shock!! Thai Farmers are still in 2.14: OAE allow Kasetsart University to Analyze Deep Information for Agricultural Plan Restructuring. https://www.matichon.co.th/economy/news_291897 (in Thai)

National Economic and Social Development Board Office, 2017. New Generation Farmers for the Future of Thailand. The Public Seminar on Mobilizing the 12th National 5-years Plan for Future of Thailand. NESDB, Thailand (in Thai).

Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research (PUIER), 2018. Microscopic view of Thailand’s agriculture through the lens of farmer registration and census data, PUIER, Bangkok Thailand, (in Thai).

Tapanapunnititkul, Onanong, 2014. Entry of Young Generation into Farming in Thailand. FFTC-RDA International Seminar on Enhancing Entry of Young Generation into Farming in Thailand, October 20-24, Jeonju, Korea.. http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=330.

Date submitted: Oct. 1, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Oct. 24, 2018