ABSTRACT

The future challenges facing agriculture will require a paradigm shift from a production orientation to a market-centric orientation. There should be a mindset shifts from a traditional perspective of agriculture of production to a market-centric agribusiness model. Philippine agribusiness and food marketing systems are changing steadily in a positive way. Agriculture as a whole is a dynamic sector, offering many opportunities for entrepreneurship along the entire agribusiness value chain. But young people shun away from agriculture because they have a misconception about what is agriculture or agribusiness. In the Philippines, agriculture is often associated with poverty, risks, and hard work. Recent studies proved otherwise. The 15% drop in poverty are due to the entrepreneurial activities ranging from agriculture-related trades among poor households in rural areas to lower-end services among urban poor, along with businesses pursued by the non-poor. Furthermore, innovation in technological applications, agri-products, and business models have been attracting the Filipino youth to agriculture. Harnessing and enabling the entrepreneurial spirit and skills of young people to become successful agri-entrepreneurs will require a mindset shift, tailored support, access to adequate and affordable financing, and the appropriate enabling environment. This can only be achieved through the development of localized, innovative models and initiatives in engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship. In the end, The transformation of the Philippine Agriculture and the development of an inclusive agribusiness value chain can only be realized by catalyzing an entrepreneurial and innovation environment that starts on the farm.

Keywords: Agri-entrepreneurship, , Agribusiness, Agriculture, Youth

INTRODUCTION

From agricultural production to agribusiness models

Agriculture today is more than just a farmer simply planting a crop, growing livestock, or catching fish. It takes an ecosystem and several actors to work together to produce and to deliver the food we need. It is this dynamic and complex ecosystem that will equip agriculture to cope with the competing challenges of addressing food safety and food security, creating inclusive livelihoods, mitigating climate change and sustainably managing natural resources. Advances in agri-biotechnology and farming practices and methods have enabled farmers to become more productive, growing crops efficiently in areas most suitable for agriculture.

The future challenges facing agriculture will require a paradigm shift from a production orientation to a market-centric orientation. Sustainability of agriculture cannot be treated separately and independently. Agricultural sustainability involves the integration of the whole agri-value chain from the acquisition of inputs to farming to marketing and up recycling of agricultural wastes. It requires the integration of the whole value chain system from value creation, delivery, and capture. Thus, there should be a mindset shifts from a traditional perspective of agriculture of production to a market-centric agribusiness model.

Agribusiness integrates all the components of the agri-value chain system from inputs to end products. Agribusiness as an economic sector, has the greatest impact on the national income of the Philippines serving as an economic backbone of the country. Philippine statistics shows that focusing on agri-production alone will only yield to 9 to 11% GDP. But if we integrate agri-production with agri-manufacturing or agro-processing and agri-services, its impact on the Philippine GDP increases to 38 to 40%.

Agribusiness can generates hundreds of jobs, produces major commodities for domestic and international consumptions. It brings rural progress by promoting economic activities on the countryside. And Agribusiness has the potential to serve as a catalyst to sustain agricultural production and ultimately, reduce rural poverty significantly. (insert here case in Africa)

But promoting the mindset shift from agriculture production to agribusiness means that the different actors - government, academe, and the industry should work together and to innovate continuously. Promoting innovation in agribusiness must start from the education of the youth towards agribusiness management employment and the promotion of inclusive agri-entrepreneurship. Such broadened collaboration will result in the creation of a fully integrated and innovative agri-value chain system that will not only assure the supply of inputs and goods but as well as human capital with relevant industry competencies.

Agri-entrepreneurship in the agribusiness value chain

Philippine agribusiness and food marketing systems are changing steadily in a positive way. As always perceived in the past decades, the Philippines with each rich natural resource has the agricultural potential not only to feed itself but also to produce a surplus that can contribute to global food security. However, fulfilling this potential requires looking at the needs of the Filipino farmers as part of food systems and supply chains and considering agricultural productivity, food security, food safety, and nutrition towards a balanced investment on the different sectors of the economy to achieve social stability and alleviates poverty.

Even with rural to urban migration occurring in the Philippines brought about by the surge of business process outsourcing companies (BPOs) and call centers, there are still many young people living in the countryside. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) report1 in 2013, youth are two times more likely than adults to be unemployed. This is brought about by the mismatch between the labor supply and demand for skills. A 2017 study by India-based employment solutions firm Aspiring Minds showed that only one out of three Filipino college graduates is “employable,” which means about 65 percent of graduates in the country do not have the right skills and training to qualify for the jobs they are applying for2.

The high unemployment rate for the youth in rural areas presents both an immense challenge and great opportunity. Generally, young people shun away from agriculture because they have a misconception about what is agriculture or agribusiness. In the Philippines, agriculture is often associated with poverty, risks, and hard work. The condition of farmers in rural areas also discourages the youth from pursuing a college education in agricultural courses. What is more alarming is that even Filipino farmers would dissuades their children to get into agriculture as a career.

But in reality, agriculture as a whole is a dynamic sector, offering many opportunities for entrepreneurship along the entire agribusiness value chain. The growing population in urban centers and the rise of the middle classes with a projected growth of 72%, are demanding more nutritious, varied and processed food. This trend in shifting consumer preference results to new jobs creation and opening various entrepreneurial opportunities in agricultural communities and for the enterprising youth. Not only population in metro-cities are growing but also populations in many municipalities and towns around the country are also increasing. These new market growths provides opportunities closer to farming communities which can generate new local jobs along the agribusiness value chain.

Given the growing markets in the country and the shifting costumer preferences, there is a need to renew a generational interest on agri-entrepreneurship and to developed young innovation-driven farmers to replace the current farmers expected to retire in a decade or so. This can be done by stimulating entrepreneurial activities in agriculture, through targeted agricultural entrepreneurship education Entrepreneurship shifts attention from producing more of the same things to producing value-added goods and services through managed agricultural risks. To encourage opportunity seeking and value creation in this sector, there is need to train current farmers to become more entrepreneurial and to educate future generations to become agricultural entrepreneurs (Santiago and Roxas, 2015)3.

The 2018 Philippine Economic Update (PEU), "Investing in the Future," by the World Bank stated that the steady economic growth for more than three decades have reduced poverty in the Philippines. But because it still is among the highest in Asia, poverty continues to be a major challenge. But the 2018 PEU report also found a positive news regarding the reduction in poverty4.

The 2018 PEU report further stated that the 15 percent drop in poverty are due to the entrepreneurial activities ranging from agriculture-related trades among poor households in rural areas to lower-end services among urban poor, along with businesses pursued by the non-poor. Entrepreneurial income from agriculture-related activities offers an opportunity to reduce rural poverty if efforts are make to address productivity constraints, access to finance, extension services, and climate change.

These agri-entrepreneurs may not have been trained formally, but they all have an instinct for innovation and business opportunity – that unique mindset that can spot and explore opportunities for socio-economic benefits. Turning entrepreneurial spirit into a business primarily requires access to financing, the provision of relevant education or vocational training together with business management training, and better links to markets for individuals and groups.

Awakening the ENTREPRENEURIAL SPIRIT of the Filipino Youth

Yet, there are many roadblocks to entrepreneurial success. Young entrepreneurs are always challenged by the limited access to finance, low levels or mismatch competencies. This is further complicated by the limited access to markets and inapplicable institutional policy and support.

Innovation, often regarded as a pre-condition for successful entrepreneurship, is usually positively related to an entrepreneur’s level of education in most developed and emerging countries6. As Phil Hogan, the European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development said, “Innovation is not only driven by technological advances. It is also through novel ways of organizing farmers and connecting them to the information they need. Many smallholder farmers around the world still farm the same way their ancestors did thousands of years ago. Traditional farming approaches may continue to work for some, but new practices can help many to substantially improve yields, soil quality and natural capital as well as food and nutrition security. The farming community needs improved access to new technologies, new business models and new forms of cooperation.”

The introduction and application of new emerging technologies and information and communication technologies in agriculture open new doors for the youth to explore agri-entrepreneurship along the agribusiness value chain. There is a re-surging interest in modern and sustainable agricultural and a renewed support for agri-entrepreneurship brought about by the partnership among the academe-government-industry on building a working innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem. This has slowly enticed many young people to try agri-entrepreneurship as a career. Thus, innovation in technological applications, agri-products, and business models have been attracting the Filipino youth to agriculture.

Engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship

Although the Filipino youth literacy rate has been increasing since 2003 to 98.11% up from 95%, youths in the rural areas who are engaged in agricultural production are generally poor mainly due to limited access to quality secondary and college education which then places them at a severe disadvantage when choosing a career. Therefore, targeted support (such as tailored trainings, access to technology, and mentoring) and an enabling environment that allows young people in the rural areas to develop professionally could help them to reach their full potential. Adapting education curricula and skills training in rural areas to particular needs would be an important step in supporting the rural youth in becoming agri-entrepreneurs along the agribusiness value chain.

Below are some innovative models and initiatives in the Philippines in engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship:

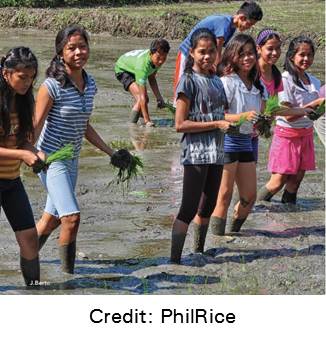

PhilRice Infomediary Campaign: Youth engagement initiative7

The campaign uses the school as the nucleus of agricultural extension. Students serve as “infomediaries” who facilitate access to information on cost-reducing and yield-enhancing technologies on rice. The idea is to reach out to the individual households of rice farmers through their children who go to school. These young people must be mobilized to serve as information providers in their rice-farming communities. As infomediaries, they can either read publications, send queries, or search information on rice and share what they found to their farmer-parents or any farmer in their community.

The Campaign aims to achieve the following: 1. To create alternative communication pathways in agricultural extension; 2. To bring back the love for rice farming and its science among young people; and 3. To promote agriculture as a viable career option for college.

Since 2012, the Campaign has been a collaboration between the Technical-Vocational Unit of the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Department of Agriculture-Philippine Rice Research Institute. In the last quarter of 2013, a partnership agreement between PhilRice and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CGIAR-CCAFS) was signed. Hence, since last quarter of 2013, the DepEd and CGIAR-CCAFS have been the two major partners of the Campaign. The Campaign has 108 sites nationwide as of 2015. From this number, 81 are TecVoc high schools. Most of these schools have already been integrating lessons on cost-reducing and yield-enhancing rice production technologies. More recently, focus has been given to climate smart rice agriculture in their school curriculum.

In 2015, the Campaign was among the featured youth engagement in agriculture projects worldwide in the 42nd session of the United Nations Committee on World Food Security in the Food and Agriculture Organization Headquarters in Rome, Italy (UN CFS, 2015).

Approach

The Campaign heavily uses action research to its advantage. There are plenty of reasons for doing this. First, the campaign is initiated by PhilRice, an organization that is at the forefront of generating knowledge on rice farming. Crucial to its function is conducting aggressive research. Second, the implementers are also keen on influencing policies, not just implementing a one-shot campaign. To make effective recommendations, a strong research component is a must. Third, while knowledge generation and policy recommendations are important, there are issues and problems that need prompt actions from the government and private sector. Hence, the Campaign is also bent on implementing solutions.

MFI Foundation, Inc.: Farm Business Schools (FBS) Model8

Mr. Jose Rene C. Gayo hatched the farm business school concept back in the 1990s. Mr. Gayo is an agribusiness graduate of Siliman University and the founding dean of the UA&P School of Management.

MFI-FBI was formed to address the need for a post-secondary family farm school program. The family farm school, on which the new institute builds, offers a high school curriculum on the basics of agriculture, adapted by the Philippines from France and Spain in 1988. MFI has partnered with the Management Association of the Philippines (MAP) and the University of Rizal System to offer the ladderized BS Entrepreneurial Management major in Farm Business. Its first batch of students was accepted into the program in 2009 at the MFI Farm Business Institute, a 60-hectare farm in Jala-jala, Rizal, Philippines. At the MFI FBI, students live on-campus and are given intensive on-farm training along with management-related courses. The students are encouraged to start profit-making projects during the course of their study.

Approach

Aspiring agri-entrepreneurs will live in the 60-hectare MFI Farm Business Institute (MFI-FBI) in Jala-Jala, Rizal and for 24 hours a day in some weeks of the year, they will be tasked to manage their farm businesses, whether these involve livestock, poultry, aquaculture, crops or agroforestry.

In the farm campus, students will dedicate 30% of their hours to classroom instruction, leaving 70% for hands-on application of agri-entrepreneurship practices. A first in the Philippines, the spacious MFI-FBI is situated in the town of Jala-Jala, a lakeshore town along Laguna de Bay in the province of Rizal.

MFI-FBI offers Technical Education and Skills Development Authority-accredited program which will lead to a Bachelor of Science in Entrepreneurship degree under the ladderized program. It incorporates a three-year diploma course in Entrepreneurship, major in Farm Business.

The Gawad Kalinga Foundation (GK): The Social Enterprise Model9

GK is a non-government organization that sprang from a desire to help build community. It began with volunteers building houses for the poor and eventually evolved to include education, health, environment, and livelihood (Habaradas & Aquino, 2010)10. In 2011, GK officially launched the GK Center for Social Innovation (CSI). Its target is to generate 500,000 social entrepreneurs who will create five million jobs in agriculture, technology, and tourism⎯ending poverty for five million⎯by 2024 (Meloto, 2011)11. GK launched the program in the GK Enchanted Farm, which serves as a business incubator for enterprises in agriculture. The 34-hectare farm in Angat, Bulacan, is the first of 24 such sites that the CSI hopes to establish in major provinces.

Approach

The GK Enchanted Farm are made up of three components: 1. “University Village” for sustainable community development; 2. “Silicon Valley” for social entrepreneurship; and 3. “Disneyland” for social tourism (GK, 2014)12. For its first site, GK invited families to relocate to an unproductive farmland, where volunteers built their homes in an adjacent area. Then, GK invited young college graduates to start enterprise using the farmland produce as the main ingredients of their products or to employ the community members. In exchange, the entrepreneurs could sell their farm-processed goods in the village farm, which attracts thousands of local and foreign tourists weekly through various activities organized by GK. From the social innovation concept arose Bayani Brew, a brand of healthy drinks; Golden Duck, producer of turmeric soaked salted duck eggs; Gourmet Keso, producer of artisan cheeses; Theo&Philo Artisan Chocolates, producer of artisan chocolates; and Human Nature, producer of personal care products. The CEO of GK, Antonio Meloto, claims that the GK Enchanted Farm is the first farm village university in the world. The GK model uses its village farms as a live business incubator for budding entrepreneurs from middle-class families in urban areas.

The young entrepreneurs are required to follow fair-trade policies, and by doing so are able to market their produce as GK brands. As their businesses prosper, the communities they work with prosper as well. Meloto envisions that the community workers will develop entrepreneurial skills due to their exposure to the young entrepreneurs. Once they have saved enough, the community workers can start their own enterprises (Meloto, personal communication, August 20, 2012). Already, community workers have begun to venture into small home-based businesses (Dehesa, 2013)13.

Kapatid Agri Mentor ME Program (KAMMP). Collaboration Model of Agri-entrepreneurship

KAMMP is program developed through the collaboration of Go Negosyo, the Department of Agriculture through Agriculture Training Institute (ATI) and leading agri-entrepreneurs in the country to equip agri-entrepreneurs with the proper production technique and to align the agri-entrepreneurs’ mindset and values to successfully run an agri enterprise.

KAMMP also teaches agri-entrepreneurs with practical knowledge and strategies to expand their business. Agri-entrepreneurs will also be given the chance to consult mentors about their current business status. And lastly, KAMMP aims to nurture a community of dynamic, competitive, and sustainable agri-preneurs14.

Approach

KAMMP is using an eight-module program on different functional areas of entrepreneurship. KAMMP program is a three-day session covering the eight modules namely: Entrepreneurial mind setting, marketing, basic accounting, farm operation management, agri supply and value chain, finance, obligations and contracts, and business plan development. The modules are designed to strengthen our farmers’ business acumen.

KAMMP is targeting the younger generation to see that there is money and success in agriculture. Its mission is to empower the youth to pursue agriculture in order to secure the country’s future. It envisions to develop the next generation of agri-entrepreneurs and farmers who will feed the whole nation.

CONCLUSION

Markets are the basis of rapidly developing agribusiness value chains that provide opportunities for entrepreneurship and employment for the Filipino youth and the growing unemployed populations. Although young people often see agriculture as associated with poverty and risk, the sector is full of opportunities waiting to be harnessed. Harnessing and enabling the entrepreneurial spirit and skills of young people to become successful agri-entrepreneurs will require a mindset shift, tailored support, access to adequate and affordable financing, and the appropriate enabling environment. This can only be achieved through the development of localized, innovative models and initiatives in engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship. In the end, the transformation of the Philippine Agriculture and the development of an inclusive agribusiness value chain can only be realized by catalyzing an entrepreneurial and innovation environment that starts on the farm.

#Agripreneurshipisagamechanger

1. International Labour Organisation, Global employment trends for youth: A generation at risk. (2013)

2. https://www.philstar.com/business/2017/10/05/1745836/only-1-out-3-graduates-employable-study shows#x2IAFkjlxQe79263.99

3. Santiago, A., & Roxas, F. (2015). Reviving farming interest in the Philippines through agricultural entrepreneurship education. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, (4), 15–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.016

4. Author. Philippine Economic Update: Investing in the Future, World Bank Manila Office. (2018).

5. Glatzel, K., et’al. Small and Growing: Entrepreneurship in African Agriculture, Montpellier Panel Report, Agriculture for Impact. (June 2014)

6. Herrington, M. and Kelley, D. African Entrepreneurship: Sub-Saharan Regional Report, (2012)

˙7. http//:www.infomediary4d.com

8. https://www.mfi.org.ph/news/mfi-jalajala-expands-agribusiness-educ-progr...

9. Santiago, A., & Roxas, F. (2015). Reviving farming interest in the Philippines through agricultural entrepreneurship education. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, (4), 15–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.016

10. Habaradas, R. & Aquino, M. (2010). Gawad Kalinga: Innovation in the city (and beyond) (Working Paper Series 2010-01C). Manila: De La Salle University-Angelo King Institute. Retrieved from http://gk1world.com/innovation-in-the-city-%28and-beyond%29

11. Meloto, T. (2011). P-Noy at the GK Enchanted Farm. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Gawad Kalinga Community Development Foundation. Retrieved from http://gk1world.com/p-noy-at-the-gk-enchanted-farm

12. Gawad Kalinga. (2014). About the Gawad Kalinga Enchanted Forest. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Author. Retrieved from http://www.gk1world.com/gk-enchanted-farm

13. Dehesa, T. (2013). The journey out of poverty. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Gawad Kalinga Community Development Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.gk1world.com/journey-out-of-poverty

14. https://www.philstar.com/business/2017/07/12/1718944/equipping-agri-entrepreneurs#mht3VPKrOSIR8uf5.99

|

Date submitted: Oct. 1, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Oct. 23, 2018

|

Best Practices of Agri-entrepreneurs in the Philippines

ABSTRACT

The future challenges facing agriculture will require a paradigm shift from a production orientation to a market-centric orientation. There should be a mindset shifts from a traditional perspective of agriculture of production to a market-centric agribusiness model. Philippine agribusiness and food marketing systems are changing steadily in a positive way. Agriculture as a whole is a dynamic sector, offering many opportunities for entrepreneurship along the entire agribusiness value chain. But young people shun away from agriculture because they have a misconception about what is agriculture or agribusiness. In the Philippines, agriculture is often associated with poverty, risks, and hard work. Recent studies proved otherwise. The 15% drop in poverty are due to the entrepreneurial activities ranging from agriculture-related trades among poor households in rural areas to lower-end services among urban poor, along with businesses pursued by the non-poor. Furthermore, innovation in technological applications, agri-products, and business models have been attracting the Filipino youth to agriculture. Harnessing and enabling the entrepreneurial spirit and skills of young people to become successful agri-entrepreneurs will require a mindset shift, tailored support, access to adequate and affordable financing, and the appropriate enabling environment. This can only be achieved through the development of localized, innovative models and initiatives in engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship. In the end, The transformation of the Philippine Agriculture and the development of an inclusive agribusiness value chain can only be realized by catalyzing an entrepreneurial and innovation environment that starts on the farm.

Keywords: Agri-entrepreneurship, , Agribusiness, Agriculture, Youth

INTRODUCTION

From agricultural production to agribusiness models

Agriculture today is more than just a farmer simply planting a crop, growing livestock, or catching fish. It takes an ecosystem and several actors to work together to produce and to deliver the food we need. It is this dynamic and complex ecosystem that will equip agriculture to cope with the competing challenges of addressing food safety and food security, creating inclusive livelihoods, mitigating climate change and sustainably managing natural resources. Advances in agri-biotechnology and farming practices and methods have enabled farmers to become more productive, growing crops efficiently in areas most suitable for agriculture.

The future challenges facing agriculture will require a paradigm shift from a production orientation to a market-centric orientation. Sustainability of agriculture cannot be treated separately and independently. Agricultural sustainability involves the integration of the whole agri-value chain from the acquisition of inputs to farming to marketing and up recycling of agricultural wastes. It requires the integration of the whole value chain system from value creation, delivery, and capture. Thus, there should be a mindset shifts from a traditional perspective of agriculture of production to a market-centric agribusiness model.

Agribusiness integrates all the components of the agri-value chain system from inputs to end products. Agribusiness as an economic sector, has the greatest impact on the national income of the Philippines serving as an economic backbone of the country. Philippine statistics shows that focusing on agri-production alone will only yield to 9 to 11% GDP. But if we integrate agri-production with agri-manufacturing or agro-processing and agri-services, its impact on the Philippine GDP increases to 38 to 40%.

Agribusiness can generates hundreds of jobs, produces major commodities for domestic and international consumptions. It brings rural progress by promoting economic activities on the countryside. And Agribusiness has the potential to serve as a catalyst to sustain agricultural production and ultimately, reduce rural poverty significantly. (insert here case in Africa)

But promoting the mindset shift from agriculture production to agribusiness means that the different actors - government, academe, and the industry should work together and to innovate continuously. Promoting innovation in agribusiness must start from the education of the youth towards agribusiness management employment and the promotion of inclusive agri-entrepreneurship. Such broadened collaboration will result in the creation of a fully integrated and innovative agri-value chain system that will not only assure the supply of inputs and goods but as well as human capital with relevant industry competencies.

Agri-entrepreneurship in the agribusiness value chain

Philippine agribusiness and food marketing systems are changing steadily in a positive way. As always perceived in the past decades, the Philippines with each rich natural resource has the agricultural potential not only to feed itself but also to produce a surplus that can contribute to global food security. However, fulfilling this potential requires looking at the needs of the Filipino farmers as part of food systems and supply chains and considering agricultural productivity, food security, food safety, and nutrition towards a balanced investment on the different sectors of the economy to achieve social stability and alleviates poverty.

Even with rural to urban migration occurring in the Philippines brought about by the surge of business process outsourcing companies (BPOs) and call centers, there are still many young people living in the countryside. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) report1 in 2013, youth are two times more likely than adults to be unemployed. This is brought about by the mismatch between the labor supply and demand for skills. A 2017 study by India-based employment solutions firm Aspiring Minds showed that only one out of three Filipino college graduates is “employable,” which means about 65 percent of graduates in the country do not have the right skills and training to qualify for the jobs they are applying for2.

The high unemployment rate for the youth in rural areas presents both an immense challenge and great opportunity. Generally, young people shun away from agriculture because they have a misconception about what is agriculture or agribusiness. In the Philippines, agriculture is often associated with poverty, risks, and hard work. The condition of farmers in rural areas also discourages the youth from pursuing a college education in agricultural courses. What is more alarming is that even Filipino farmers would dissuades their children to get into agriculture as a career.

But in reality, agriculture as a whole is a dynamic sector, offering many opportunities for entrepreneurship along the entire agribusiness value chain. The growing population in urban centers and the rise of the middle classes with a projected growth of 72%, are demanding more nutritious, varied and processed food. This trend in shifting consumer preference results to new jobs creation and opening various entrepreneurial opportunities in agricultural communities and for the enterprising youth. Not only population in metro-cities are growing but also populations in many municipalities and towns around the country are also increasing. These new market growths provides opportunities closer to farming communities which can generate new local jobs along the agribusiness value chain.

Given the growing markets in the country and the shifting costumer preferences, there is a need to renew a generational interest on agri-entrepreneurship and to developed young innovation-driven farmers to replace the current farmers expected to retire in a decade or so. This can be done by stimulating entrepreneurial activities in agriculture, through targeted agricultural entrepreneurship education Entrepreneurship shifts attention from producing more of the same things to producing value-added goods and services through managed agricultural risks. To encourage opportunity seeking and value creation in this sector, there is need to train current farmers to become more entrepreneurial and to educate future generations to become agricultural entrepreneurs (Santiago and Roxas, 2015)3.

The 2018 Philippine Economic Update (PEU), "Investing in the Future," by the World Bank stated that the steady economic growth for more than three decades have reduced poverty in the Philippines. But because it still is among the highest in Asia, poverty continues to be a major challenge. But the 2018 PEU report also found a positive news regarding the reduction in poverty4.

The 2018 PEU report further stated that the 15 percent drop in poverty are due to the entrepreneurial activities ranging from agriculture-related trades among poor households in rural areas to lower-end services among urban poor, along with businesses pursued by the non-poor. Entrepreneurial income from agriculture-related activities offers an opportunity to reduce rural poverty if efforts are make to address productivity constraints, access to finance, extension services, and climate change.

These agri-entrepreneurs may not have been trained formally, but they all have an instinct for innovation and business opportunity – that unique mindset that can spot and explore opportunities for socio-economic benefits. Turning entrepreneurial spirit into a business primarily requires access to financing, the provision of relevant education or vocational training together with business management training, and better links to markets for individuals and groups.

Awakening the ENTREPRENEURIAL SPIRIT of the Filipino Youth

The Filipino youth is 19.4 million strong with a growth rate of 2.11% annually. Comparing to the rest of the world, Filipinos are younger with a median age of 23 years old. This median age of 23 years old is equivalent to the age of a recently graduated from college and generally considered as the most productive stage in a person’s life.

The Montpellier Panel Report (2014) described young people as, “dynamic, inquisitive and challenging. Everywhere in the world they create a distinctive culture, are innovative and often invent new forms of independent work.” The report stated also that young entrepreneurs are also more likely to hire fellow youths and pull even more young people out of unemployment and poverty. They are particularly responsive to new economic opportunities and trends and are active in high growth sectors. Further, entrepreneurship offers unemployed or discouraged youth an opportunity to build sustainable livelihoods and a chance to integrate into society5.

Yet, there are many roadblocks to entrepreneurial success. Young entrepreneurs are always challenged by the limited access to finance, low levels or mismatch competencies. This is further complicated by the limited access to markets and inapplicable institutional policy and support.

Innovation, often regarded as a pre-condition for successful entrepreneurship, is usually positively related to an entrepreneur’s level of education in most developed and emerging countries6. As Phil Hogan, the European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development said, “Innovation is not only driven by technological advances. It is also through novel ways of organizing farmers and connecting them to the information they need. Many smallholder farmers around the world still farm the same way their ancestors did thousands of years ago. Traditional farming approaches may continue to work for some, but new practices can help many to substantially improve yields, soil quality and natural capital as well as food and nutrition security. The farming community needs improved access to new technologies, new business models and new forms of cooperation.”

The introduction and application of new emerging technologies and information and communication technologies in agriculture open new doors for the youth to explore agri-entrepreneurship along the agribusiness value chain. There is a re-surging interest in modern and sustainable agricultural and a renewed support for agri-entrepreneurship brought about by the partnership among the academe-government-industry on building a working innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem. This has slowly enticed many young people to try agri-entrepreneurship as a career. Thus, innovation in technological applications, agri-products, and business models have been attracting the Filipino youth to agriculture.

Engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship

Although the Filipino youth literacy rate has been increasing since 2003 to 98.11% up from 95%, youths in the rural areas who are engaged in agricultural production are generally poor mainly due to limited access to quality secondary and college education which then places them at a severe disadvantage when choosing a career. Therefore, targeted support (such as tailored trainings, access to technology, and mentoring) and an enabling environment that allows young people in the rural areas to develop professionally could help them to reach their full potential. Adapting education curricula and skills training in rural areas to particular needs would be an important step in supporting the rural youth in becoming agri-entrepreneurs along the agribusiness value chain.

Below are some innovative models and initiatives in the Philippines in engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship:

PhilRice Infomediary Campaign: Youth engagement initiative7

The campaign uses the school as the nucleus of agricultural extension. Students serve as “infomediaries” who facilitate access to information on cost-reducing and yield-enhancing technologies on rice. The idea is to reach out to the individual households of rice farmers through their children who go to school. These young people must be mobilized to serve as information providers in their rice-farming communities. As infomediaries, they can either read publications, send queries, or search information on rice and share what they found to their farmer-parents or any farmer in their community.

The Campaign aims to achieve the following: 1. To create alternative communication pathways in agricultural extension; 2. To bring back the love for rice farming and its science among young people; and 3. To promote agriculture as a viable career option for college.

Since 2012, the Campaign has been a collaboration between the Technical-Vocational Unit of the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Department of Agriculture-Philippine Rice Research Institute. In the last quarter of 2013, a partnership agreement between PhilRice and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CGIAR-CCAFS) was signed. Hence, since last quarter of 2013, the DepEd and CGIAR-CCAFS have been the two major partners of the Campaign. The Campaign has 108 sites nationwide as of 2015. From this number, 81 are TecVoc high schools. Most of these schools have already been integrating lessons on cost-reducing and yield-enhancing rice production technologies. More recently, focus has been given to climate smart rice agriculture in their school curriculum.

In 2015, the Campaign was among the featured youth engagement in agriculture projects worldwide in the 42nd session of the United Nations Committee on World Food Security in the Food and Agriculture Organization Headquarters in Rome, Italy (UN CFS, 2015).

Approach

The Campaign heavily uses action research to its advantage. There are plenty of reasons for doing this. First, the campaign is initiated by PhilRice, an organization that is at the forefront of generating knowledge on rice farming. Crucial to its function is conducting aggressive research. Second, the implementers are also keen on influencing policies, not just implementing a one-shot campaign. To make effective recommendations, a strong research component is a must. Third, while knowledge generation and policy recommendations are important, there are issues and problems that need prompt actions from the government and private sector. Hence, the Campaign is also bent on implementing solutions.

MFI Foundation, Inc.: Farm Business Schools (FBS) Model8

Mr. Jose Rene C. Gayo hatched the farm business school concept back in the 1990s. Mr. Gayo is an agribusiness graduate of Siliman University and the founding dean of the UA&P School of Management.

MFI-FBI was formed to address the need for a post-secondary family farm school program. The family farm school, on which the new institute builds, offers a high school curriculum on the basics of agriculture, adapted by the Philippines from France and Spain in 1988. MFI has partnered with the Management Association of the Philippines (MAP) and the University of Rizal System to offer the ladderized BS Entrepreneurial Management major in Farm Business. Its first batch of students was accepted into the program in 2009 at the MFI Farm Business Institute, a 60-hectare farm in Jala-jala, Rizal, Philippines. At the MFI FBI, students live on-campus and are given intensive on-farm training along with management-related courses. The students are encouraged to start profit-making projects during the course of their study.

Approach

Aspiring agri-entrepreneurs will live in the 60-hectare MFI Farm Business Institute (MFI-FBI) in Jala-Jala, Rizal and for 24 hours a day in some weeks of the year, they will be tasked to manage their farm businesses, whether these involve livestock, poultry, aquaculture, crops or agroforestry.

In the farm campus, students will dedicate 30% of their hours to classroom instruction, leaving 70% for hands-on application of agri-entrepreneurship practices. A first in the Philippines, the spacious MFI-FBI is situated in the town of Jala-Jala, a lakeshore town along Laguna de Bay in the province of Rizal.

MFI-FBI offers Technical Education and Skills Development Authority-accredited program which will lead to a Bachelor of Science in Entrepreneurship degree under the ladderized program. It incorporates a three-year diploma course in Entrepreneurship, major in Farm Business.

The Gawad Kalinga Foundation (GK): The Social Enterprise Model9

GK is a non-government organization that sprang from a desire to help build community. It began with volunteers building houses for the poor and eventually evolved to include education, health, environment, and livelihood (Habaradas & Aquino, 2010)10. In 2011, GK officially launched the GK Center for Social Innovation (CSI). Its target is to generate 500,000 social entrepreneurs who will create five million jobs in agriculture, technology, and tourism⎯ending poverty for five million⎯by 2024 (Meloto, 2011)11. GK launched the program in the GK Enchanted Farm, which serves as a business incubator for enterprises in agriculture. The 34-hectare farm in Angat, Bulacan, is the first of 24 such sites that the CSI hopes to establish in major provinces.

Approach

The GK Enchanted Farm are made up of three components: 1. “University Village” for sustainable community development; 2. “Silicon Valley” for social entrepreneurship; and 3. “Disneyland” for social tourism (GK, 2014)12. For its first site, GK invited families to relocate to an unproductive farmland, where volunteers built their homes in an adjacent area. Then, GK invited young college graduates to start enterprise using the farmland produce as the main ingredients of their products or to employ the community members. In exchange, the entrepreneurs could sell their farm-processed goods in the village farm, which attracts thousands of local and foreign tourists weekly through various activities organized by GK. From the social innovation concept arose Bayani Brew, a brand of healthy drinks; Golden Duck, producer of turmeric soaked salted duck eggs; Gourmet Keso, producer of artisan cheeses; Theo&Philo Artisan Chocolates, producer of artisan chocolates; and Human Nature, producer of personal care products. The CEO of GK, Antonio Meloto, claims that the GK Enchanted Farm is the first farm village university in the world. The GK model uses its village farms as a live business incubator for budding entrepreneurs from middle-class families in urban areas.

The young entrepreneurs are required to follow fair-trade policies, and by doing so are able to market their produce as GK brands. As their businesses prosper, the communities they work with prosper as well. Meloto envisions that the community workers will develop entrepreneurial skills due to their exposure to the young entrepreneurs. Once they have saved enough, the community workers can start their own enterprises (Meloto, personal communication, August 20, 2012). Already, community workers have begun to venture into small home-based businesses (Dehesa, 2013)13.

Kapatid Agri Mentor ME Program (KAMMP). Collaboration Model of Agri-entrepreneurship

KAMMP is program developed through the collaboration of Go Negosyo, the Department of Agriculture through Agriculture Training Institute (ATI) and leading agri-entrepreneurs in the country to equip agri-entrepreneurs with the proper production technique and to align the agri-entrepreneurs’ mindset and values to successfully run an agri enterprise.

KAMMP also teaches agri-entrepreneurs with practical knowledge and strategies to expand their business. Agri-entrepreneurs will also be given the chance to consult mentors about their current business status. And lastly, KAMMP aims to nurture a community of dynamic, competitive, and sustainable agri-preneurs14.

Approach

KAMMP is using an eight-module program on different functional areas of entrepreneurship. KAMMP program is a three-day session covering the eight modules namely: Entrepreneurial mind setting, marketing, basic accounting, farm operation management, agri supply and value chain, finance, obligations and contracts, and business plan development. The modules are designed to strengthen our farmers’ business acumen.

KAMMP is targeting the younger generation to see that there is money and success in agriculture. Its mission is to empower the youth to pursue agriculture in order to secure the country’s future. It envisions to develop the next generation of agri-entrepreneurs and farmers who will feed the whole nation.

CONCLUSION

Markets are the basis of rapidly developing agribusiness value chains that provide opportunities for entrepreneurship and employment for the Filipino youth and the growing unemployed populations. Although young people often see agriculture as associated with poverty and risk, the sector is full of opportunities waiting to be harnessed. Harnessing and enabling the entrepreneurial spirit and skills of young people to become successful agri-entrepreneurs will require a mindset shift, tailored support, access to adequate and affordable financing, and the appropriate enabling environment. This can only be achieved through the development of localized, innovative models and initiatives in engaging and capacitating the youth on agri-entrepreneurship. In the end, the transformation of the Philippine Agriculture and the development of an inclusive agribusiness value chain can only be realized by catalyzing an entrepreneurial and innovation environment that starts on the farm.

#Agripreneurshipisagamechanger

1. International Labour Organisation, Global employment trends for youth: A generation at risk. (2013)

2. https://www.philstar.com/business/2017/10/05/1745836/only-1-out-3-graduates-employable-study shows#x2IAFkjlxQe79263.99

3. Santiago, A., & Roxas, F. (2015). Reviving farming interest in the Philippines through agricultural entrepreneurship education. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, (4), 15–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.016

4. Author. Philippine Economic Update: Investing in the Future, World Bank Manila Office. (2018).

5. Glatzel, K., et’al. Small and Growing: Entrepreneurship in African Agriculture, Montpellier Panel Report, Agriculture for Impact. (June 2014)

6. Herrington, M. and Kelley, D. African Entrepreneurship: Sub-Saharan Regional Report, (2012)

˙7. http//:www.infomediary4d.com

8. https://www.mfi.org.ph/news/mfi-jalajala-expands-agribusiness-educ-progr...

9. Santiago, A., & Roxas, F. (2015). Reviving farming interest in the Philippines through agricultural entrepreneurship education. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, (4), 15–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.016

10. Habaradas, R. & Aquino, M. (2010). Gawad Kalinga: Innovation in the city (and beyond) (Working Paper Series 2010-01C). Manila: De La Salle University-Angelo King Institute. Retrieved from http://gk1world.com/innovation-in-the-city-%28and-beyond%29

11. Meloto, T. (2011). P-Noy at the GK Enchanted Farm. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Gawad Kalinga Community Development Foundation. Retrieved from http://gk1world.com/p-noy-at-the-gk-enchanted-farm

12. Gawad Kalinga. (2014). About the Gawad Kalinga Enchanted Forest. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Author. Retrieved from http://www.gk1world.com/gk-enchanted-farm

13. Dehesa, T. (2013). The journey out of poverty. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Gawad Kalinga Community Development Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.gk1world.com/journey-out-of-poverty

14. https://www.philstar.com/business/2017/07/12/1718944/equipping-agri-entrepreneurs#mht3VPKrOSIR8uf5.99

Date submitted: Oct. 1, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Oct. 23, 2018