ABSTRACT

The impacts of climate change on cooperatives are a growing concern that needs to be urgently addressed for a cooperative to become competitive and sustainable in the long run. This paper presents the cooperative case for going green where opportunities and prospects for greening the practices and business activities of Philippine cooperatives are tackled in the context of enhancing their competitiveness, resilience, and sustainability. Issues and constraints to mainstream green practices in their operations and management are also discussed with corresponding recommendations to address them. In this study, two agri-based cooperatives namely, the Green Beans Multipurpose Cooperative and the Calamba Vegetable Growers Marketing Cooperative were featured to demonstrate how cooperatives can adopt green practices. Results showed that cooperatives are capable of integrating green practices in their operations and in doing so, can promote sustainable food marketing in terms of reducing their operating costs, recapturing value from their products and byproducts, enhancing their resiliency, and using natural resources efficiently. However, some of the identified issues and constraints to realizing these impacts were the lack of awareness or inadequacy of knowledge and understanding of the greening strategy, the failure to assess the greenness of their cooperative activities, the limited resources to support the adoption of more green practices, and the weak policy institution to support the greening of cooperatives. Among the recommendations of the study were to strengthen green education among cooperatives; develop more support mechanisms such as green financing; and review the existing cooperative policies to explore the possibility of institutionalizing the greening of cooperatives.

Key words: agricultural cooperatives, green practices, sustainability, Philippines

INTRODUCTION

Over the next few decades, the Philippines is expected to require greater food supplies due to burgeoning population and changes in consumer food preferences and expectations for food quality and standards. Meeting the expanding food demand is foreseen to be more challenging as food production and distribution are faced with environmental threats and increasing impacts of climate change. With the natural assets remaining scarce, productivity improvements will be needed in all phases of food commodity value chains in order to meet the changing consumer demands and market requirements amid the changing climate. In pursuit of improving productivity however, it is important to ensure the sustainability of the growth process through more efficient use of natural resources and improved resilience to climate impacts. The “business as usual” may not work anymore if one has to deal with the increasing risks and pressures brought about by climate change and environmental degradation while aiming for increased productivity and enhanced competitiveness.

It is in this context that a kind of productivity growth that does not compromise environmental and social responsibilities or promotes minimization of tradeoffs between economic and social and environmental sustainability is deemed more appropriate. This growth path, which encourages shifting from the “grow first, clean up later” to the “grow clean, grow more later” practice is what green growth strategy promotes. Technically, green growth can be defined as “a means to foster economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies” (OECD 2011). This strategy can be adopted at all levels of the economy, from global or national down to industry/market, business/organization, community, or household level. Yet, a joint greening effort that cuts across different market levels and deals with the vulnerable sectors can create more significant growth impact compared to individual greening actions.

Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which make up 99.6% of all enterprises in the country, play a significant role in food marketing and are a key contributor to the economic growth. MSMEs include the cooperatives whose majority (76%) fall under the micro category or have total assets of not more than US$60,000 (PhP3.0 million). Cooperatives in particular assume different roles in food value chains, where they can act as input suppliers, producers, consolidators, processors, wholesalers, retailers, and/or as final markets or end consumers. With their multiple market roles and people-centered nature of their businesses, cooperatives can be a strategic entry point for promoting green growth. However, maximizing cooperatives’ full potential as catalysts of green growth require adequate knowledge, capacity, and willingness to support the strategy. Their resilience to the impacts of climate change is also a factor that has to be developed, given that MSMEs are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to their limited resources and sensitivity to prices (Antonio, et al. 2015).

This study analyzed the opportunities and prospects of cooperatives for adopting and promoting green growth strategy in their business activities and operations. It attempted to answer the following research questions using evidences from the cases of Calamba Vegetable Growers Marketing Cooperative (CVGMC) and Green Beans Multipurpose Cooperative (GBMPC)[1] and other related survey information generated for the study:

- Are cooperatives capable of adopting and promoting green growth strategy?

- What benefits can cooperatives reap from doing green practices?

- What could be the issues and constraints that cooperatives face in going green and how can these be addressed?

- What are the implications of greening cooperatives to sustainability of food marketing?

The paper is organized into four sections. The first section explains the link between cooperatives and green growth. The second presents the opportunities for and benefits of doing green activities. The third discusses the issues and constraints in going green as supported by the results of the case study of CVGMC and GBMPC. The last section concludes the paper by stating the significance of green growth initiatives of cooperatives to sustainable food marketing and the way forward to promote greening among cooperatives.

COOPERATIVES AND GREEN GROWTH NEXUS

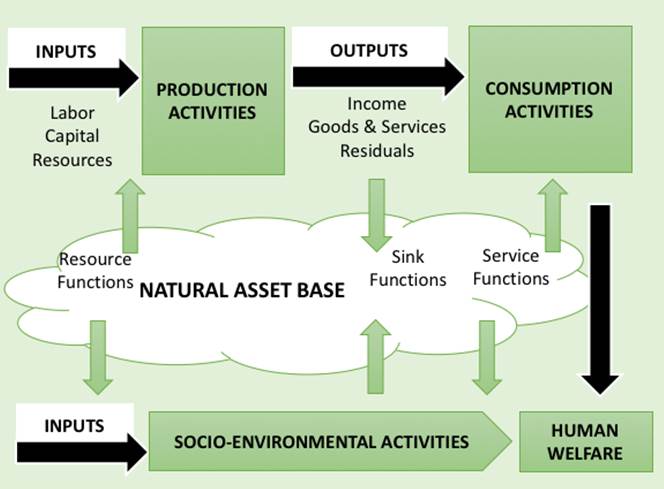

A cooperative enterprise grows by carrying out key economic activities which include production and consumption as well as socio-environmental activities as part of its concern for community (Figure 1). These activities require natural resources to make and deliver outputs that are aimed at improving welfare of the cooperative members. In production, natural asset base serves as the key source of inputs for producing outputs. These outputs then flow through the market to reach the consumers, which also involves the use of natural resources to do exchange, physical and facilitating marketing functions. The natural asset base also serves as the sink for production wastes, pollutants and residues. In consumption activities, natural assets provide the environmental services needed to ensure health and safety of consumers and again serve as the absorber of wastes from the goods and services consumed. Socio-environmental activities also require natural resources as inputs to deliver services to cooperative members and target communities. The socioeconomic activities of a cooperative are highly dependent on natural assets, thus in order to sustain its activities, the availability of natural assets must also be sustained.

Fig. 1. Natural asset functions in cooperative activities

Sustainability and cooperatives are directly linked with each other. Cooperatives are builders of sustainability, which is inherent in the nature of cooperatives. They can make positive contributions to sustainability, and therefore to green growth too. Anchored to the three pillars of sustainable development – economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection, cooperatives are described in the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA)’s Blueprint for a Co-operative Decade as “highly sustainable businesses, combining financial health, environmental concern and social purpose in a triple bottom line.” They are based on the values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity, and solidarity and on the principles of concern for community. The cooperative principle of “concern for community,” states that “cooperatives have a special responsibility to ensure that the development of communities – economically, socially and culturally, is sustained. They have a responsibility to work steadily for the environmental protection of their communities” (Republic Act 9520, Philippine Cooperative Code of 2008).

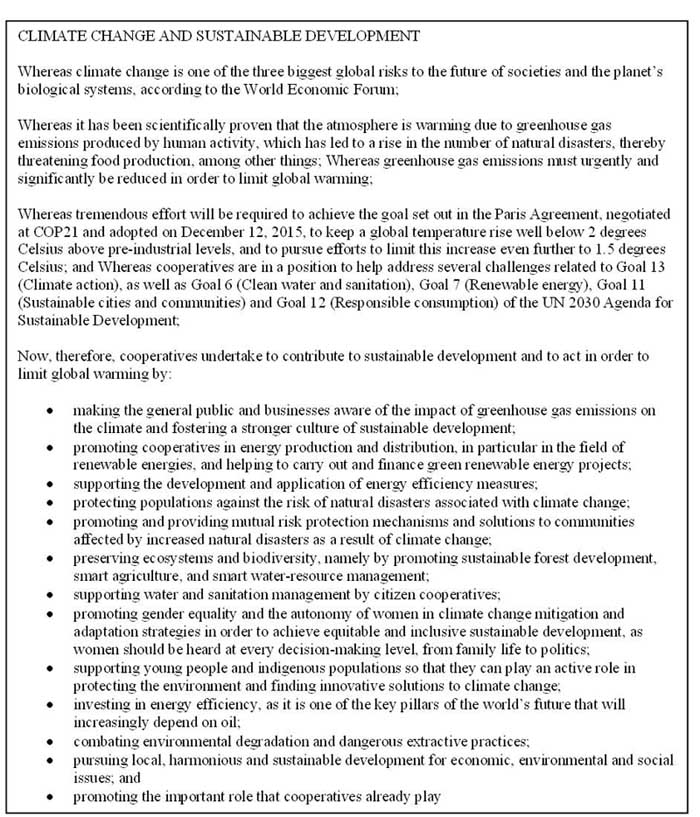

During the Third International Summit of Cooperatives in 2016, the cooperative movement set for itself the objective to act on social, environmental and economic issues and fulfill its role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The movement’s Power to Act Declaration emphasizes that cooperatives are in a position to introduce sustainable development strategies in different societies. It has a specific section tackling the actions that can be taken by cooperatives to support climate change- and green growth-related SDGs (Appendix 1).

Given the general characteristics and nature of cooperatives and their commitment to sustainable development, integrating greening in the management and operations of a cooperative can be a justifiable business strategy. For the purpose of this study, greening refers to the use of processes, business practices, technologies that reduce adverse impact on the environment; promote efficient use of power, water, resources and raw materials; improve solid and wastewater management; reduce air and water pollution and climate-related risks; and produce green products and services (ProGED 2016). It is a strategy that could complement the strategies for cooperative enterprise development by balancing the economic, social and environmental objectives of the cooperative; making the cooperative enterprises sustainable; promoting resource-efficient production; finding or creating clean sources of growth; and providing opportunity to enhance cooperative competitiveness.

WHY GREEN THE COOPERATIVES

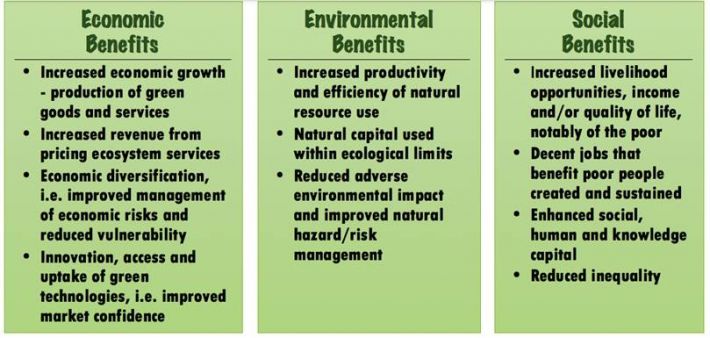

A critical question in the decision to engage in greening practices is what are the benefits of going green. Several literature have already articulated the advantages or benefits of pursuing green growth strategies. Generally, moving towards cleaner and greener sources of growth may deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits such as those listed below.

Fig. 2. General benefits of going green

Source: OECD (2012)

At enterprise level, integrating green practices in business strategies can address the negative impacts of climate change, enhance the enterprise competitiveness and ensure its sustainability and survival (ProGED 2014). Specifically, going green can help enhance competitiveness and long term sustainability by reducing operating costs, gaining access to markets and niche markets, and enhancing resiliency (Antonio, et al. 2015). Increased resource efficiency (e.g., reducing power and water consumption) for instance, will not only reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emission but will also reduce costs, thereby generating savings (Antonio and Finkel 2010). With consumers’ increasing awareness of their environmental responsibilities, an enterprise can create a unique selling point and stand out against its conventional competitors by building its identity as a green and sustainable business. It can create new income streams that can increase current sales through greening products and services. Developing own sources of resources such as power and water, for example by investing in solar power and/or rainwater harvesting facility can cushion the enterprise from the impacts of fluctuating prices and enhance business resiliency in times of shortage or lack of power and water resources for instance due to extreme weather events (ProGED 2015). Employees may also benefit in working in a green enterprise or having green jobs in terms of improving their morale, health, and productivity.

Fig. 3. Benefits of greening an enterprise

Sources: ProGED. (2014) and Carbon Trust (2012)

Greening a cooperative enterprise involve sustainable business practices that may require low, high or no investment. Some of the examples of green strategies that can be adopted are the following:

- Reducing energy consumption, for instance by shifting to energy efficient lighting fixtures (e.g., compact fluorescent (CFL) or light emitting diode (LED) bulbs) and appliances. The Promotion of Green Economic Development (ProGED) program of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and the Philippine Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) had a comparison of the cost savings that can be generated from using energy efficient light bulbs.

Table 1. Sample cost and savings computation from energy efficiency measures

|

Description

|

LED

|

CFL

|

Incandescent

|

|

Light bulb projected lifespan

|

50,000 hours

|

10,000 hours

|

1,200 hours

|

|

Watts per bulb (equivalent to 60 watts)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Cost per bulb

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Cost of electricity (@ 0.10 per kilowatt hour)

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Bulbs needed for 50,000 hours bulb

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Equivalent 50,000 hours bulb expense

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Total cost for 50,000 hours

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Sample savings computation: Energy savings over 50,000 hours, assuming 25 bulbs per household

|

|

Total cost for 25 bulbs

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

Savings to household by switching from incandescent bulb

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

Source: ProGED (2014)

- Reducing water consumption, examples of these are rainwater harvesting and use of low flow plumbing fixtures

- Wastewater management, for instance through installation of wastewater treatment facility

- Solid waste management by recycling and/or composting of of waste materials

- Material efficiency by using less or alternative material to produce a particular product thereby translating to less waste. This also involves shifting to greener production process and product design.

- Construction of green building design that allow for natural lighting and ventilation, which minimizes the use of electricity.

- Greening the supply chain, wherein suppliers are encouraged to green their operations and producers to source their inputs locally and do bulk purchasing to reduce carbon emissions, lower energy consumption, and minimize use of chemicals and more efficient use of raw materials. This also includes encouraging consumers to patronize goods and services manufactured or delivered using green processes (e.g., naturally grown agricultural commodities)

It is unfortunate that at present, there is a dearth in evidence-based literature that demonstrate the quantitative benefits of green practices among cooperatives. However, various studies were already done for enterprises in general, which can be applicable to cooperatives too. In one of the studies of the European Union under its SWITCH-Asia Program (as cited in Antonio, et al. 2015), entitled Green Philippine Islands of Sustainability (GPIoS), savings from resource efficiency measures of enterprises were estimated. Table 2 shows a sample computation of savings generated by select enterprises involved in manufacturing and food marketing services that participated in the project.

Other common green practices are listed in Table 4. The point of laying down the green practices here is to present the possible areas for greening the cooperative. These wide options indicate there is a range of opportunities for cooperatives to green their operations and business activities. Depending on its key goals and its desired benefits, the cooperative can identify the environmental hotspots where it has been contributing to or suffering from. It can then select and prioritize the green practices that could adopted, given their resources and capabilities, to move towards a low-carbon, climate-resilient, resource-efficient, clean and sustainable growth path.

Two general criteria are often considered in prioritizing green practice – synergy and urgency. Prioritizing based on synergy is considering the extent to which green practices provide immediate and local benefits to the cooperative and promote a faster and/or a more inclusive growth. Urgency, on the other hand, is basing the priority on the extent to which a green practice can be or cannot be postponed depending on the risk of irreversible damages or locking into unsustainable growth patterns that is associated with it.

Table 2. Sample savings computation from resource efficiency measures

|

Name of enterprise

|

Batis Asul Caterers

|

Calfurn Manufacturing Philippines Incorporated

|

Oasis Hotel

|

|

Nature of business

|

Catering services/ events venue

|

Export/manufacturing (rattan and wood furniture)

|

Services (Hotel, restaurant and bar)

|

|

Number of employees

|

58

|

508

|

151

|

|

Implemented measures

|

• Proper storage of soap and chemicals

• Established standards for proper food handling

• Bulk purchasing

• Use of vinegar instead of chlorinated cleaning agents

• Replacement of aerosol spray with isopropyl alcohol for pest control

• Repair of refrigerator magnets/

• Daily energy/ water consumption monitoring

• Replacement of plastic bags with reusable bags for transporting linens

• Repainting of the roof of the ballroom to a lighter color

• Installation of rainwater catchment facility

|

• Improved waste management by selling used cartons

• Installation of natural lighting system

• Implementing planned cluster trips of delivery trucks

|

• Energy conservation measures (i.e., turning off lights and aircon in vacant rooms)

• Regular maintenance of equipment (freezer, aircon)

• Establishment of waste segregation area

• Disposal of fully depreciated kitchen and other hotel equipment

• Replacement of window type aircons w/ split type

• Bulk purchasing of supplies

|

|

Savings

|

• Reduction of power consumption by 35%, annual savings of US$2,370 (PhP118,500)

• Reduction of water consumption by 40%, annual savings of US$2,206 (PhP110,300)

• Reduction in the use of hazardous chemicals, annual savings of US$322 (PhP16,100)

• Reduction of food and residual waste, annual savings of US$1,180 (PhP59,000)

|

• Reduction of mixed waste, annual savings of US$600 (PhP30,000)

• Reduction of power consumption by 1%, annual savings of US$800 (PhP40,000)

• Reduction of diesel consumption for transportation by 66%, annual savings of US$4,600 (PhP230,000)

|

• Reduction of paper consumption by 10%, annual savings of US$360 (PhP18,000)

• Reduction of mixed waste, annual savings through additional income of US$2,000 (PhP100,000)

|

|

Investment and payback period

|

Low Investment: US$396 (PhP19,800)

Payback: 0.8 months

|

Mid Investment: US$1,000 (PhP50,000)

Payback: 2 months

|

High Investment: US$20,000 (PhP1.0 million)

Payback: 8.4 months

|

Note: US$1.00 = PhP50.00

Source: Antonio et al. (2015)

ISSUES AND CONSTRAINTS IN GOING GREEN

Lack of Awareness/Inadequate Knowledge on Greening

In the previous section, the benefits of going green as well as the possible green practices that can be adopted in order to reap those benefits were presented. This information establishes the fact that cooperatives can indeed take a green growth path by shifting to more sustainable or greener practices. However, if such information is not known to the cooperatives, it is most likely that they may not be able to take the opportunities in greening their operations and benefit from a greener business strategy. In another research of ProGED (Hiemann 2013), it was particularly pointed out that information and awareness on greening is an important line of intervention for MSMEs to adopt climate-smart and environment-friendly strategies. Similarly, in the study of Pabuayon, et al. (2016) on greening of Philippine cooperatives, the lack of awareness and information on green practices also appeared as one of the issues that need to be addressed in pushing green cooperatives in the country.

The level of knowledge on greening has an implication on the belief in and support of cooperative stakeholders for promoting and adopting green practices. Using the case of CVGMC and GBMPC of which the profiles are described in Appendix 2, the knowledge, attitude and perception of cooperative members, which included officers, manager/management staff, and non-officer members, on greening cooperatives were examined through a simple quick survey before and after undergoing a one-day capacity building training on greening cooperatives. From a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest), 18 respondents were asked to rate themselves in terms of the following criteria:

- Knowledge on greening practices (knowledge);

- Support on the promotion and adoption of greening practices (attitude); and

- Belief in the benefits of going green (perception).

Table 3. Knowledge, attitude and perception of CVGMC and GBMPC members on greening cooperatives before and after training, Laguna, Philippines, 2017 (n=18 respondents)

|

Criteria

|

Score (Rating Scale)

|

No answer

|

|

1.00 to 4.00 (Low)

|

4.01 to 7.00 (Fair)

|

7.01 to 10.00 (High)

|

|

|

No.

|

%

|

No.

|

%

|

No.

|

%

|

|

Before training

|

|

Knowledge

|

4

|

22

|

5

|

28

|

5

|

44

|

4 (6%)

|

|

Attitude

|

1

|

6

|

4

|

22

|

11

|

61

|

2 (11%)

|

|

Perception

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

17

|

14

|

78

|

1 (6%)

|

|

After training

|

|

Knowledge

|

1

|

6

|

4

|

22

|

10

|

56

|

3 (16%)

|

|

Attitude

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

17

|

12

|

67

|

3 (16%)

|

|

Perception

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

16

|

89

|

2 (11%)

|

Source: Quilloy and Cruz (2017)

With an increase in the knowledge of cooperative members on green growth strategies and practices, more respondents rated their attitude and perception toward green practices with scores greater than 4. From 61% and 78% of respondents rating their attitude and perception with high scores, the percentage of respondents increased to 67% and 89% respectively. These results imply that raising awareness of cooperatives on green growth strategies and their applications to cooperatives can have positive effects on the promotion and adoption of green practices.

Failure to Assess the Greenness of Cooperative Activities

Another issue related to awareness and information is the failure of cooperatives to regularly assess whether or not its operations and business activities are environment-friendly, resource-efficient, and climate-smart and to determine the level of the “greenness” of their cooperatives based on the number of green practices that they adopt.

A short survey involving 26 members from 11 cooperatives was randomly conducted by the Institute of Cooperatives and Bio-Enterprise Development (ICOPED) during one of its cooperative seminars to have a general idea of cooperatives’ extent of adoption of green practices.[2] Survey results showed that while 80% of the participants indicated that they are doing green practices, a common observation is the limited number of activities that they adopt, ranging only from one (1) to three (3) practices. The most common green practices were tree planting activity, recycling, and waste management. The lack of awareness of other options for greening their activities constrains them from addressing environmental hotspots, thereby limiting them to contribute better to sustainable growth. If one is able to assess its current practices as to whether green or not and to identify the other opportunities for greening its activities, it can maximize its capability of going green and gain more benefits from it. Without green audit, cooperatives might continue to contribute to environmental degradation and climate change and miss the opportunities to take green practices that they do not know they are capable of doing.

The two case cooperatives, CVGMC and GBMPC, when asked if they have ever done a green audit of their businesses, both responded that they have not done it yet. As a result, they have not realized that with same amount of their resources, they can do more green practices, until they finally did a green audit. The green audit template serves both as a checklist of green practices that a cooperative can adopt and as an instrument for measuring the degree of the greenness of the cooperative. Being aware of the current green status of the cooperative and the areas where greening can still be adopted through green audit can guide the cooperatives on their greening process. This has been proven by the results of the green audit exercise done by CVGMC and GBMPC right after their capacity building training on greening cooperatives and three weeks after undergoing the training.

In the green audit exercise, the two cooperatives were asked to accomplish a green audit form, where they have to indicate the green practices that they are doing and give each practice a score of 3 if they fully adopt the practice, 1 if they are partially doing it, and 0 if they are currently not doing the green practice. They were also asked to denote whether they have plans of doing the green practice in the future. The comparative results of the exercise provided evidences of the positive outcome of doing green audit. Both cooperatives improved their green scores as they were able to engage in more green practices and willing to do more, given the same set of resources, compared to when they were not yet guided by green audit (Table 4).

Limited Resources to Invest in Green Practices

While there are green practices that only require behavioral change and do not require any financial investment, cooperatives should not be limited to adopting only these kinds of practices (e.g., checking lighting and controls, doing waste segregation, and saving office materials). More opportunities to create greater impact and gain more benefits are available if a cooperative can integrate more green practices in its operations. However, high-impact green practices such as the use of climate-smart and green technologies often require mid to high initial capital investments, which micro cooperatives usually do not have. In effect, they are constrained to just practicing low impact green practices.

Table 4. Green audit results of CVGMC and GBMPC, Laguna, Philippines, 2017

|

Green Practices

|

CVGMC

|

GBMPC

|

|

1st Green Audit (May 5)

|

2nd Green Audit (May 26)

|

1st Green Audit (May 5)

|

2nd Green Audit (May 26)

|

|

Improve Environmental and Climate Awareness and Knowledge

|

|

Incorporate green in the cooperatives Vision, Mission and Goals

|

|

|

|

|

|

Advertise “green credentials” in documents & communications

|

|

x

|

|

|

|

Communicate green in packaging, website, office signage

|

|

x

|

|

|

|

Publicize green accreditations and certifications

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conduct training to cooperative members on benefits of green and green practices

|

|

|

|

x

|

|

Give preference to suppliers that implement green practices

|

|

x

|

|

x

|

|

Reduce Energy and Emissions

|

|

Check lighting and controls

|

|

3

|

|

3

|

|

Install energy efficiency lighting (i.e. LED, solar-powered)

|

|

|

|

3

|

|

Collect and record energy consumption information

|

|

x

|

|

|

|

Set targets on energy consumption

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check water usage and controls

|

|

3

|

|

3

|

|

Capture and store water

|

|

x

|

|

3

|

|

Check faucets, pipes and toilets for leaks

|

3

|

3

|

|

3

|

|

Install water-saving devices in business or farm operations

|

|

3

|

|

x

|

|

Collect and record water consumption information

|

|

|

|

|

|

Set targets on water consumption

|

|

|

|

|

|

Manage Resources and Wastes

|

|

Send information electronically to save paper

|

|

|

|

3

|

|

Do waste segregation and recycling

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Implement efficient waste disposal systems

|

3

|

3

|

|

|

|

Collect and record waste information

|

3

|

3

|

|

|

|

Set targets on waste for reduction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reduce, reuse, recycle materials in business and farm operations

|

|

x

|

3

|

3

|

|

Check vehicle usage and reduce unnecessary trips/journeys

|

|

x

|

|

|

|

Check and maintain vehicles regularly

|

3

|

3

|

|

|

|

Invest in Green and Climate Smart Technology

|

|

Make and use compost

|

3

|

3

|

|

x

|

|

Repair and improve drainage

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Reduce cultivations

|

3

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

Target fertilizer applications to soil conditions, crop requirements and weather

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Explore opportunities to build organic materials and use legumes to fix Nitrogen

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Limit the use of chemical fertilizer

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Use improved (e.g. climate-resistant) crop varieties

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

TOTAL GREEN SCORE

|

36

|

45

|

21

|

40

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: The listed green practices were selected based on existing literature, best practices of farmer-members of some cooperatives, technical recommendations from government experts and academic consultants provided during a consultation workshop done by Quilloy and Cruz (2017).

“x” indicates that the green practice has been added to the plan of action of the cooperative.

Source: Quilloy and Cruz (2017)

This constraint has been recognized by various organizations and agencies promoting green growth in the Philippines like DTI, Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP), Department of Agriculture, National Economic and Development Authority, and international development organizations (e.g., GTZ and Global Green Growth Institute, ). Programs and projects to assist enterprises like cooperatives in pursuing green strategies have been implemented by these institutions to enable them to expand their green actions. With capital investment as a critical requirement in adopting high-impact green practices, LBP, a government bank in the country, has particularly established green financing programs for agri-based enterprises. These programs are intended to finance projects and activities that seek to address climate change and environmental threats.

An example of green financing program of LBP is its Climate Resilient Agriculture Financing Program. The program aims to provide credit assistance to promote climate change mitigation and adaptation initiatives towards climate resilient agriculture and to address climate change risks and helps nurture innovation development at community level. It can finance adaptation and mitigation projects such as climate-resilient technologies (e.g., controlled irrigation system) and infrastructure, adaptive planting calendar, use of improved crop varieties, terracing and system of rice intensification, establishment of windbreaks, rainwater harvesting, biogas digester, and facilities for hydroponics and aquaponics.

Another response to the limited financial resources constraining the cooperatives from adopting green practices is enabling the cooperatives to properly prioritize the green practices that they can implement based on a certain set of criteria that are deemed important to them. In a prioritizing exercise done by CVGMC and GBMPC, the cost and ease of implementation appeared to be one of the key criteria in identifying which among the green practices that they have chosen can be first implemented. The prioritization process involved giving weights to the set criteria and giving score to each green practice selected, wherein the top five practices with the highest scores will be prioritized for implementation. This exercise guides the appropriate allocation of available resources to green practices that the cooperative is willing and able to implement. Table 5 presents the results of prioritization done by the two case cooperatives.

Table 5. Prioritized green practices of CVGMC and GBMPC, Laguna, Philippines, 2017

|

CVGMC

|

GBMPC

|

|

Make & use compost

|

Waste segregation

|

|

Waste segregation

|

Waste reduction

|

|

Record and collect energy data

|

Incorporate greening in the cooperative vision and mission

|

|

Check lighting

|

Save paper by communicating electronically

|

|

Limit use of chemical fertilizer

|

Conduct training on greening

|

Note: Criteria set by cooperatives in the prioritization were the following: (1) low cost of implementation; (2) highest savings potential; (3) availability of required resources; (4) ease of implementation; and (5) speed of translation into benefits.

Support for Greening Not Institutionalized

It is clear that the global cooperative movement is committed to support the SDGs, including the climate change mitigation and adaptation and environmental conservation actions. At national level, the government is also in full support of achieving the SDGs, making them part of the strategies in the current Philippine Development Plan as well as in its MSME Development Plan. Policies, laws and regulations related to environmental protection and resource conservation (e.g., Renewable Energy Act, Biofuels Act, Clean Air Act, Mini-Hydroelectric Power Incentives Act, Clean Water Act, etc.) have been implemented to strengthen the country’s actions towards a greener growth. However, this is not the case in the cooperative sector. While there is the cooperative principle of “concern for community” that covers the environmental responsibility of a cooperative, such principle does not compel any cooperative to specifically integrate green practices in its operations nor legally apprehend it from not doing so.

This is one of the reasons for cooperatives’ poor adoption of green practices identified during the Consultation Workshop on Greening Cooperatives for Sustainable Growth conducted by Quilloy and Cruz last April 25, 2017. In the case of CVGMC and GBMPC, it was found out that both cooperatives do not have any statement in their bylaws and in their vision and mission that specifically mentions the need to promote and practice greening (Quilloy and Cruz 2017). The suggestion therefore during the consultation was to explore the possibility of institutionalizing the greening of cooperatives or the adoption and promotion of green practices in the Philippine Cooperative Code. This will emphasize the importance of going green and reinforce the cooperative movement’s initiatives to promote green growth as cooperatives will then be compelled to develop and implement green actions.

IMPLICATIONS TO SUSTAINABLE FOOD MARKETING

Agri-based cooperatives play multiple roles in the food value chains. As mentioned earlier, they can be present at all levels of the chain, doing various marketing functions to deliver the good or service to the end users. Hence, when a cooperative goes green, greater impact can be created in terms of greening the value chain thereby making food marketing sustainable, especially if it assumes more market roles.

What is interesting to note is the fact that most of the green strategies discussed in this paper are applicable at various level of a value chain and can be done by different market players. For instance, energy and water efficiency measures, waste management, and use of environment-friendly materials can be done by a cooperative involved in production, processing, wholesaling, or retailing stage. Improvement of environmental and climate awareness through conduct of trainings can also be carried out by cooperative at any stage of the chain, hence reaching more market players, including consumers.

The case of CVGMC and GBMPC, which are engaged in production and marketing of fresh vegetables and green coffee beans respectively, demonstrates how cooperatives can contribute to making agri-food marketing sustainable. Integrating green practices, which include resource and waste management practices and adoption of sustainable agricultural practices (i.e., limited use of chemical fertilizer, use of climate-resilient crop varieties, composting, and improved drainage), in the activities of CVGMC and GBMPC is a clear indication that cooperatives are capable of adopting green growth strategy in their businesses and making an impact on sustainable food marketing.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

A wide range of opportunities to go green can be explored by Philippine cooperatives. They can focus on several areas of greening, where they can apply green practices that they are capable of doing. To maximize their greening potentials, cooperatives must have the following enabling factors: (1) adequate knowledge on green growth strategy and practices; (2) awareness on the degree of greenness of own activities; (3) access to green financing and other resources; and (4) policy institution that support the greening of cooperatives.

Particularly, it is recommended that the cooperative sector together with other sectors supporting the cooperatives strengthen its green growth awareness campaigns and information drives through capacity building activities in order to develop a positive mindset towards greening and educate the cooperatives on various greening opportunities. It is suggested that these capacity building activities also include green audit and green practice prioritization exercises to better guide the cooperatives in their greening process. Development of more support mechanisms like green financing and incentives programs that are accessible to the cooperatives is also suggested to further encourage the adoption of green practices. Lastly, there might be a need to review the existing policies and laws concerning cooperatives (i.e., the Philippine Cooperative Code of 2008) to determine how greening can be institutionalized. Such action can streamline the individual green efforts of cooperatives and strengthen the implementation of more green practices, which can help increase the contributory impact of the whole cooperative sector to the environment.

With all these recommendations, cooperatives can foster enhanced competitiveness and sustainable food marketing in the advent of climate change and environmental degradation through a more resilient, resource efficient, and environment-friendly business strategies while at the same time contributing to achieving a greener growth for the economy and realizing the goals of sustainable development.

REFERENCES

Antonio, M.A., R. Capio, M. Bacalso, and N. Ritsma. 2015. Promotion of Green Economic Development (ProGED) Approach. Reference Document. Bonn, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Antonio, V. and T. Finkel. 2010. Integrating Green Growth Strategies into the 2011-2016 MSME Development Strategy. Strategy Brief No. 4. Makati City: Private Sector Promotion (SMEDSEP) Program Office

Carbon Trust. 2012. Green your Business for Growth. Management Guide. London: The Carbon Trust

Cooperatives: The Power to Act Declaration. International Summit of Cooperatives. October 11-13, 2016. Quebec, Canada. Available at https://www.sommetinter.coop/sites/default/files/library/declaration_finale_eng_2016.pdf

Hiemann. W. 2013. Green Finance for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in the Philippines. Makati: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

OECD. 2011. Towards Green Growth. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

_______. 2012. Green Growth and Developing Countries. Consultation Draft.

Pabuayon, I.M., B.R. Pantoja, A.B. Vista, and A.C. Manila. 2016. Greening of Philippine Cooperatives: Integrating Business and Environmental Objectives for Competitiveness. Project seminar paper presented on December 21, 2016 at ICOPED Auditorium.

ProGED. 2014. Greening Enterprises for Enhanced Competitiveness. ProGED Videos. Accessed August 10, 2017 at http://greeneconomy.ph/proged-videos/

______. 2016. Climate Change and MSMEs Competitiveness. ProGED Videos. Accessed August 10, 2016 at http://greeneconomy.ph/proged-videos/

Quilloy, K.P. and L.S. Cruz. 2017. Leveraging Philippine Agricultural Cooperatives for Green Growth: A Pilot Study. Final project report submitted to ASEAN CSR Network, Ltd., Singapore.

Appendix 1. Excerpts from Cooperatives: The Power to Act Declaration

Source: Cooperatives: The Power to Act Declaration. International Summit of Cooperatives. October 11-13, 2016. Quebec, Canada. Available at https://www.sommetinter.coop/sites/default/files/library/declaration_fin...

Appendix 2. Profile of CVGMC and GBMPC, Laguna Philippines, December 2016

|

Calamba Vegetable Growers Marketing Cooperative (CVGMC)

|

|

Address

|

Looc, Calamba City, Laguna, Philippines

|

|

Category of cooperative

|

Primary; micro cooperative

|

|

Type of cooperative

|

Multipurpose

|

|

Business activities

|

Production, marketing, agricultural equipment rental

|

|

Commodities handled

|

Vegetables (tomato, bottle gourd, squash, etc.)

|

|

Membership

|

52

|

|

Total assets

|

PhP824,647 (US$17,363.74)

|

|

Total net surplus

|

PhP10,906 (US$229.64)

|

|

Green Beans Multipurpose Cooperative (GBMPC)

|

|

Address

|

Banlic, Calamba City, Laguna, Philippines

|

|

Category of cooperative

|

Primary; micro cooperative

|

|

Type of cooperative

|

Multipurpose

|

|

Business activities

|

Production, marketing

|

|

Commodities handled

|

Coffee beans

|

|

Membership

|

43

|

|

Total assets

|

PhP1,754,473 (US$36,942.13)

|

|

Total net surplus

|

PhP5,854 (US$123.26)

|

Note: exchange rate: PHP1.00 = US$0.0211

Sources: 2016 Annual Reports of CVGMC and GBMPC

[1] CVGMC and GBMPC were the case cooperatives used in the action research entitled “Leveraging Philippine Agri-based Cooperatives for Green Growth: A Pilot Study,” which was implemented by Quilloy and Cruz (2017) under the funding of the ASEAN CSR Network, Ltd., Singapore.

[2] Survey was conducted among the cooperative participants who attended the Seminar on “Amendments on Cooperative Guidelines: Issuance of Certificate of Compliance, and Exemption from Payment of Local Taxes, Fees, and Charges” held last February 15, 2017 at ICOPED Auditorium, CEM, UPLB, College, Laguna.

| Submitted as a country paper for the FFTC-NTIFO International Seminar on Enhancing Agricultural Cooperatives’ Roles in Response to Changes in Food Consumption Trends, Sept. 18-22, Taipei, Taiwan |

Greening Opportunities and Prospects for Philippine Cooperatives toward a More sustainable Food Marketing

ABSTRACT

The impacts of climate change on cooperatives are a growing concern that needs to be urgently addressed for a cooperative to become competitive and sustainable in the long run. This paper presents the cooperative case for going green where opportunities and prospects for greening the practices and business activities of Philippine cooperatives are tackled in the context of enhancing their competitiveness, resilience, and sustainability. Issues and constraints to mainstream green practices in their operations and management are also discussed with corresponding recommendations to address them. In this study, two agri-based cooperatives namely, the Green Beans Multipurpose Cooperative and the Calamba Vegetable Growers Marketing Cooperative were featured to demonstrate how cooperatives can adopt green practices. Results showed that cooperatives are capable of integrating green practices in their operations and in doing so, can promote sustainable food marketing in terms of reducing their operating costs, recapturing value from their products and byproducts, enhancing their resiliency, and using natural resources efficiently. However, some of the identified issues and constraints to realizing these impacts were the lack of awareness or inadequacy of knowledge and understanding of the greening strategy, the failure to assess the greenness of their cooperative activities, the limited resources to support the adoption of more green practices, and the weak policy institution to support the greening of cooperatives. Among the recommendations of the study were to strengthen green education among cooperatives; develop more support mechanisms such as green financing; and review the existing cooperative policies to explore the possibility of institutionalizing the greening of cooperatives.

Key words: agricultural cooperatives, green practices, sustainability, Philippines

INTRODUCTION

Over the next few decades, the Philippines is expected to require greater food supplies due to burgeoning population and changes in consumer food preferences and expectations for food quality and standards. Meeting the expanding food demand is foreseen to be more challenging as food production and distribution are faced with environmental threats and increasing impacts of climate change. With the natural assets remaining scarce, productivity improvements will be needed in all phases of food commodity value chains in order to meet the changing consumer demands and market requirements amid the changing climate. In pursuit of improving productivity however, it is important to ensure the sustainability of the growth process through more efficient use of natural resources and improved resilience to climate impacts. The “business as usual” may not work anymore if one has to deal with the increasing risks and pressures brought about by climate change and environmental degradation while aiming for increased productivity and enhanced competitiveness.

It is in this context that a kind of productivity growth that does not compromise environmental and social responsibilities or promotes minimization of tradeoffs between economic and social and environmental sustainability is deemed more appropriate. This growth path, which encourages shifting from the “grow first, clean up later” to the “grow clean, grow more later” practice is what green growth strategy promotes. Technically, green growth can be defined as “a means to foster economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies” (OECD 2011). This strategy can be adopted at all levels of the economy, from global or national down to industry/market, business/organization, community, or household level. Yet, a joint greening effort that cuts across different market levels and deals with the vulnerable sectors can create more significant growth impact compared to individual greening actions.

Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which make up 99.6% of all enterprises in the country, play a significant role in food marketing and are a key contributor to the economic growth. MSMEs include the cooperatives whose majority (76%) fall under the micro category or have total assets of not more than US$60,000 (PhP3.0 million). Cooperatives in particular assume different roles in food value chains, where they can act as input suppliers, producers, consolidators, processors, wholesalers, retailers, and/or as final markets or end consumers. With their multiple market roles and people-centered nature of their businesses, cooperatives can be a strategic entry point for promoting green growth. However, maximizing cooperatives’ full potential as catalysts of green growth require adequate knowledge, capacity, and willingness to support the strategy. Their resilience to the impacts of climate change is also a factor that has to be developed, given that MSMEs are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to their limited resources and sensitivity to prices (Antonio, et al. 2015).

This study analyzed the opportunities and prospects of cooperatives for adopting and promoting green growth strategy in their business activities and operations. It attempted to answer the following research questions using evidences from the cases of Calamba Vegetable Growers Marketing Cooperative (CVGMC) and Green Beans Multipurpose Cooperative (GBMPC)[1] and other related survey information generated for the study:

The paper is organized into four sections. The first section explains the link between cooperatives and green growth. The second presents the opportunities for and benefits of doing green activities. The third discusses the issues and constraints in going green as supported by the results of the case study of CVGMC and GBMPC. The last section concludes the paper by stating the significance of green growth initiatives of cooperatives to sustainable food marketing and the way forward to promote greening among cooperatives.

COOPERATIVES AND GREEN GROWTH NEXUS

A cooperative enterprise grows by carrying out key economic activities which include production and consumption as well as socio-environmental activities as part of its concern for community (Figure 1). These activities require natural resources to make and deliver outputs that are aimed at improving welfare of the cooperative members. In production, natural asset base serves as the key source of inputs for producing outputs. These outputs then flow through the market to reach the consumers, which also involves the use of natural resources to do exchange, physical and facilitating marketing functions. The natural asset base also serves as the sink for production wastes, pollutants and residues. In consumption activities, natural assets provide the environmental services needed to ensure health and safety of consumers and again serve as the absorber of wastes from the goods and services consumed. Socio-environmental activities also require natural resources as inputs to deliver services to cooperative members and target communities. The socioeconomic activities of a cooperative are highly dependent on natural assets, thus in order to sustain its activities, the availability of natural assets must also be sustained.

Fig. 1. Natural asset functions in cooperative activities

Sustainability and cooperatives are directly linked with each other. Cooperatives are builders of sustainability, which is inherent in the nature of cooperatives. They can make positive contributions to sustainability, and therefore to green growth too. Anchored to the three pillars of sustainable development – economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection, cooperatives are described in the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA)’s Blueprint for a Co-operative Decade as “highly sustainable businesses, combining financial health, environmental concern and social purpose in a triple bottom line.” They are based on the values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity, and solidarity and on the principles of concern for community. The cooperative principle of “concern for community,” states that “cooperatives have a special responsibility to ensure that the development of communities – economically, socially and culturally, is sustained. They have a responsibility to work steadily for the environmental protection of their communities” (Republic Act 9520, Philippine Cooperative Code of 2008).

During the Third International Summit of Cooperatives in 2016, the cooperative movement set for itself the objective to act on social, environmental and economic issues and fulfill its role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The movement’s Power to Act Declaration emphasizes that cooperatives are in a position to introduce sustainable development strategies in different societies. It has a specific section tackling the actions that can be taken by cooperatives to support climate change- and green growth-related SDGs (Appendix 1).

Given the general characteristics and nature of cooperatives and their commitment to sustainable development, integrating greening in the management and operations of a cooperative can be a justifiable business strategy. For the purpose of this study, greening refers to the use of processes, business practices, technologies that reduce adverse impact on the environment; promote efficient use of power, water, resources and raw materials; improve solid and wastewater management; reduce air and water pollution and climate-related risks; and produce green products and services (ProGED 2016). It is a strategy that could complement the strategies for cooperative enterprise development by balancing the economic, social and environmental objectives of the cooperative; making the cooperative enterprises sustainable; promoting resource-efficient production; finding or creating clean sources of growth; and providing opportunity to enhance cooperative competitiveness.

WHY GREEN THE COOPERATIVES

A critical question in the decision to engage in greening practices is what are the benefits of going green. Several literature have already articulated the advantages or benefits of pursuing green growth strategies. Generally, moving towards cleaner and greener sources of growth may deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits such as those listed below.

Fig. 2. General benefits of going green

Source: OECD (2012)

At enterprise level, integrating green practices in business strategies can address the negative impacts of climate change, enhance the enterprise competitiveness and ensure its sustainability and survival (ProGED 2014). Specifically, going green can help enhance competitiveness and long term sustainability by reducing operating costs, gaining access to markets and niche markets, and enhancing resiliency (Antonio, et al. 2015). Increased resource efficiency (e.g., reducing power and water consumption) for instance, will not only reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emission but will also reduce costs, thereby generating savings (Antonio and Finkel 2010). With consumers’ increasing awareness of their environmental responsibilities, an enterprise can create a unique selling point and stand out against its conventional competitors by building its identity as a green and sustainable business. It can create new income streams that can increase current sales through greening products and services. Developing own sources of resources such as power and water, for example by investing in solar power and/or rainwater harvesting facility can cushion the enterprise from the impacts of fluctuating prices and enhance business resiliency in times of shortage or lack of power and water resources for instance due to extreme weather events (ProGED 2015). Employees may also benefit in working in a green enterprise or having green jobs in terms of improving their morale, health, and productivity.

Fig. 3. Benefits of greening an enterprise

Sources: ProGED. (2014) and Carbon Trust (2012)

Greening a cooperative enterprise involve sustainable business practices that may require low, high or no investment. Some of the examples of green strategies that can be adopted are the following:

Table 1. Sample cost and savings computation from energy efficiency measures

Description

LED

CFL

Incandescent

Light bulb projected lifespan

50,000 hours

10,000 hours

1,200 hours

Watts per bulb (equivalent to 60 watts)

Cost per bulb

Cost of electricity (@ 0.10 per kilowatt hour)

Bulbs needed for 50,000 hours bulb

Equivalent 50,000 hours bulb expense

Total cost for 50,000 hours

Sample savings computation: Energy savings over 50,000 hours, assuming 25 bulbs per household

Total cost for 25 bulbs

Savings to household by switching from incandescent bulb

Source: ProGED (2014)

It is unfortunate that at present, there is a dearth in evidence-based literature that demonstrate the quantitative benefits of green practices among cooperatives. However, various studies were already done for enterprises in general, which can be applicable to cooperatives too. In one of the studies of the European Union under its SWITCH-Asia Program (as cited in Antonio, et al. 2015), entitled Green Philippine Islands of Sustainability (GPIoS), savings from resource efficiency measures of enterprises were estimated. Table 2 shows a sample computation of savings generated by select enterprises involved in manufacturing and food marketing services that participated in the project.

Other common green practices are listed in Table 4. The point of laying down the green practices here is to present the possible areas for greening the cooperative. These wide options indicate there is a range of opportunities for cooperatives to green their operations and business activities. Depending on its key goals and its desired benefits, the cooperative can identify the environmental hotspots where it has been contributing to or suffering from. It can then select and prioritize the green practices that could adopted, given their resources and capabilities, to move towards a low-carbon, climate-resilient, resource-efficient, clean and sustainable growth path.

Two general criteria are often considered in prioritizing green practice – synergy and urgency. Prioritizing based on synergy is considering the extent to which green practices provide immediate and local benefits to the cooperative and promote a faster and/or a more inclusive growth. Urgency, on the other hand, is basing the priority on the extent to which a green practice can be or cannot be postponed depending on the risk of irreversible damages or locking into unsustainable growth patterns that is associated with it.

Table 2. Sample savings computation from resource efficiency measures

Name of enterprise

Batis Asul Caterers

Calfurn Manufacturing Philippines Incorporated

Oasis Hotel

Nature of business

Catering services/ events venue

Export/manufacturing (rattan and wood furniture)

Services (Hotel, restaurant and bar)

Number of employees

58

508

151

Implemented measures

• Proper storage of soap and chemicals

• Established standards for proper food handling

• Bulk purchasing

• Use of vinegar instead of chlorinated cleaning agents

• Replacement of aerosol spray with isopropyl alcohol for pest control

• Repair of refrigerator magnets/

• Daily energy/ water consumption monitoring

• Replacement of plastic bags with reusable bags for transporting linens

• Repainting of the roof of the ballroom to a lighter color

• Installation of rainwater catchment facility

• Improved waste management by selling used cartons

• Installation of natural lighting system

• Implementing planned cluster trips of delivery trucks

• Energy conservation measures (i.e., turning off lights and aircon in vacant rooms)

• Regular maintenance of equipment (freezer, aircon)

• Establishment of waste segregation area

• Disposal of fully depreciated kitchen and other hotel equipment

• Replacement of window type aircons w/ split type

• Bulk purchasing of supplies

Savings

• Reduction of power consumption by 35%, annual savings of US$2,370 (PhP118,500)

• Reduction of water consumption by 40%, annual savings of US$2,206 (PhP110,300)

• Reduction in the use of hazardous chemicals, annual savings of US$322 (PhP16,100)

• Reduction of food and residual waste, annual savings of US$1,180 (PhP59,000)

• Reduction of mixed waste, annual savings of US$600 (PhP30,000)

• Reduction of power consumption by 1%, annual savings of US$800 (PhP40,000)

• Reduction of diesel consumption for transportation by 66%, annual savings of US$4,600 (PhP230,000)

• Reduction of paper consumption by 10%, annual savings of US$360 (PhP18,000)

• Reduction of mixed waste, annual savings through additional income of US$2,000 (PhP100,000)

Investment and payback period

Low Investment: US$396 (PhP19,800)

Payback: 0.8 months

Mid Investment: US$1,000 (PhP50,000)

Payback: 2 months

High Investment: US$20,000 (PhP1.0 million)

Payback: 8.4 months

Note: US$1.00 = PhP50.00

Source: Antonio et al. (2015)

ISSUES AND CONSTRAINTS IN GOING GREEN

Lack of Awareness/Inadequate Knowledge on Greening

In the previous section, the benefits of going green as well as the possible green practices that can be adopted in order to reap those benefits were presented. This information establishes the fact that cooperatives can indeed take a green growth path by shifting to more sustainable or greener practices. However, if such information is not known to the cooperatives, it is most likely that they may not be able to take the opportunities in greening their operations and benefit from a greener business strategy. In another research of ProGED (Hiemann 2013), it was particularly pointed out that information and awareness on greening is an important line of intervention for MSMEs to adopt climate-smart and environment-friendly strategies. Similarly, in the study of Pabuayon, et al. (2016) on greening of Philippine cooperatives, the lack of awareness and information on green practices also appeared as one of the issues that need to be addressed in pushing green cooperatives in the country.

The level of knowledge on greening has an implication on the belief in and support of cooperative stakeholders for promoting and adopting green practices. Using the case of CVGMC and GBMPC of which the profiles are described in Appendix 2, the knowledge, attitude and perception of cooperative members, which included officers, manager/management staff, and non-officer members, on greening cooperatives were examined through a simple quick survey before and after undergoing a one-day capacity building training on greening cooperatives. From a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being the lowest and 10 being the highest), 18 respondents were asked to rate themselves in terms of the following criteria:

Table 3. Knowledge, attitude and perception of CVGMC and GBMPC members on greening cooperatives before and after training, Laguna, Philippines, 2017 (n=18 respondents)

Criteria

Score (Rating Scale)

No answer

1.00 to 4.00 (Low)

4.01 to 7.00 (Fair)

7.01 to 10.00 (High)

No.

%

No.

%

No.

%

Before training

Knowledge

4

22

5

28

5

44

4 (6%)

Attitude

1

6

4

22

11

61

2 (11%)

Perception

0

0

3

17

14

78

1 (6%)

After training

Knowledge

1

6

4

22

10

56

3 (16%)

Attitude

0

0

3

17

12

67

3 (16%)

Perception

0

0

0

0

16

89

2 (11%)

Source: Quilloy and Cruz (2017)

With an increase in the knowledge of cooperative members on green growth strategies and practices, more respondents rated their attitude and perception toward green practices with scores greater than 4. From 61% and 78% of respondents rating their attitude and perception with high scores, the percentage of respondents increased to 67% and 89% respectively. These results imply that raising awareness of cooperatives on green growth strategies and their applications to cooperatives can have positive effects on the promotion and adoption of green practices.

Failure to Assess the Greenness of Cooperative Activities

Another issue related to awareness and information is the failure of cooperatives to regularly assess whether or not its operations and business activities are environment-friendly, resource-efficient, and climate-smart and to determine the level of the “greenness” of their cooperatives based on the number of green practices that they adopt.

A short survey involving 26 members from 11 cooperatives was randomly conducted by the Institute of Cooperatives and Bio-Enterprise Development (ICOPED) during one of its cooperative seminars to have a general idea of cooperatives’ extent of adoption of green practices.[2] Survey results showed that while 80% of the participants indicated that they are doing green practices, a common observation is the limited number of activities that they adopt, ranging only from one (1) to three (3) practices. The most common green practices were tree planting activity, recycling, and waste management. The lack of awareness of other options for greening their activities constrains them from addressing environmental hotspots, thereby limiting them to contribute better to sustainable growth. If one is able to assess its current practices as to whether green or not and to identify the other opportunities for greening its activities, it can maximize its capability of going green and gain more benefits from it. Without green audit, cooperatives might continue to contribute to environmental degradation and climate change and miss the opportunities to take green practices that they do not know they are capable of doing.

The two case cooperatives, CVGMC and GBMPC, when asked if they have ever done a green audit of their businesses, both responded that they have not done it yet. As a result, they have not realized that with same amount of their resources, they can do more green practices, until they finally did a green audit. The green audit template serves both as a checklist of green practices that a cooperative can adopt and as an instrument for measuring the degree of the greenness of the cooperative. Being aware of the current green status of the cooperative and the areas where greening can still be adopted through green audit can guide the cooperatives on their greening process. This has been proven by the results of the green audit exercise done by CVGMC and GBMPC right after their capacity building training on greening cooperatives and three weeks after undergoing the training.

In the green audit exercise, the two cooperatives were asked to accomplish a green audit form, where they have to indicate the green practices that they are doing and give each practice a score of 3 if they fully adopt the practice, 1 if they are partially doing it, and 0 if they are currently not doing the green practice. They were also asked to denote whether they have plans of doing the green practice in the future. The comparative results of the exercise provided evidences of the positive outcome of doing green audit. Both cooperatives improved their green scores as they were able to engage in more green practices and willing to do more, given the same set of resources, compared to when they were not yet guided by green audit (Table 4).

Limited Resources to Invest in Green Practices

While there are green practices that only require behavioral change and do not require any financial investment, cooperatives should not be limited to adopting only these kinds of practices (e.g., checking lighting and controls, doing waste segregation, and saving office materials). More opportunities to create greater impact and gain more benefits are available if a cooperative can integrate more green practices in its operations. However, high-impact green practices such as the use of climate-smart and green technologies often require mid to high initial capital investments, which micro cooperatives usually do not have. In effect, they are constrained to just practicing low impact green practices.

Table 4. Green audit results of CVGMC and GBMPC, Laguna, Philippines, 2017

Green Practices

CVGMC

GBMPC

1st Green Audit (May 5)

2nd Green Audit (May 26)

1st Green Audit (May 5)

2nd Green Audit (May 26)

Improve Environmental and Climate Awareness and Knowledge

Incorporate green in the cooperatives Vision, Mission and Goals

Advertise “green credentials” in documents & communications

x

Communicate green in packaging, website, office signage

x

Publicize green accreditations and certifications

Conduct training to cooperative members on benefits of green and green practices

x

Give preference to suppliers that implement green practices

x

x

Reduce Energy and Emissions

Check lighting and controls

3

3

Install energy efficiency lighting (i.e. LED, solar-powered)

3

Collect and record energy consumption information

x

Set targets on energy consumption

Check water usage and controls

3

3

Capture and store water

x

3

Check faucets, pipes and toilets for leaks

3

3

3

Install water-saving devices in business or farm operations

3

x

Collect and record water consumption information

Set targets on water consumption

Manage Resources and Wastes

Send information electronically to save paper

3

Do waste segregation and recycling

3

3

3

3

Implement efficient waste disposal systems

3

3

Collect and record waste information

3

3

Set targets on waste for reduction

Reduce, reuse, recycle materials in business and farm operations

x

3

3

Check vehicle usage and reduce unnecessary trips/journeys

x

Check and maintain vehicles regularly

3

3

Invest in Green and Climate Smart Technology

Make and use compost

3

3

x

Repair and improve drainage

3

3

3

3

Reduce cultivations

3

3

1

Target fertilizer applications to soil conditions, crop requirements and weather

3

3

3

3

Explore opportunities to build organic materials and use legumes to fix Nitrogen

3

3

3

3

Limit the use of chemical fertilizer

3

3

3

3

Use improved (e.g. climate-resistant) crop varieties

3

3

3

3

TOTAL GREEN SCORE

36

45

21

40

Note: The listed green practices were selected based on existing literature, best practices of farmer-members of some cooperatives, technical recommendations from government experts and academic consultants provided during a consultation workshop done by Quilloy and Cruz (2017).

“x” indicates that the green practice has been added to the plan of action of the cooperative.

Source: Quilloy and Cruz (2017)

This constraint has been recognized by various organizations and agencies promoting green growth in the Philippines like DTI, Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP), Department of Agriculture, National Economic and Development Authority, and international development organizations (e.g., GTZ and Global Green Growth Institute, ). Programs and projects to assist enterprises like cooperatives in pursuing green strategies have been implemented by these institutions to enable them to expand their green actions. With capital investment as a critical requirement in adopting high-impact green practices, LBP, a government bank in the country, has particularly established green financing programs for agri-based enterprises. These programs are intended to finance projects and activities that seek to address climate change and environmental threats.

An example of green financing program of LBP is its Climate Resilient Agriculture Financing Program. The program aims to provide credit assistance to promote climate change mitigation and adaptation initiatives towards climate resilient agriculture and to address climate change risks and helps nurture innovation development at community level. It can finance adaptation and mitigation projects such as climate-resilient technologies (e.g., controlled irrigation system) and infrastructure, adaptive planting calendar, use of improved crop varieties, terracing and system of rice intensification, establishment of windbreaks, rainwater harvesting, biogas digester, and facilities for hydroponics and aquaponics.

Another response to the limited financial resources constraining the cooperatives from adopting green practices is enabling the cooperatives to properly prioritize the green practices that they can implement based on a certain set of criteria that are deemed important to them. In a prioritizing exercise done by CVGMC and GBMPC, the cost and ease of implementation appeared to be one of the key criteria in identifying which among the green practices that they have chosen can be first implemented. The prioritization process involved giving weights to the set criteria and giving score to each green practice selected, wherein the top five practices with the highest scores will be prioritized for implementation. This exercise guides the appropriate allocation of available resources to green practices that the cooperative is willing and able to implement. Table 5 presents the results of prioritization done by the two case cooperatives.

Table 5. Prioritized green practices of CVGMC and GBMPC, Laguna, Philippines, 2017

CVGMC

GBMPC

Make & use compost

Waste segregation

Waste segregation

Waste reduction

Record and collect energy data

Incorporate greening in the cooperative vision and mission

Check lighting

Save paper by communicating electronically

Limit use of chemical fertilizer

Conduct training on greening

Note: Criteria set by cooperatives in the prioritization were the following: (1) low cost of implementation; (2) highest savings potential; (3) availability of required resources; (4) ease of implementation; and (5) speed of translation into benefits.

Support for Greening Not Institutionalized

It is clear that the global cooperative movement is committed to support the SDGs, including the climate change mitigation and adaptation and environmental conservation actions. At national level, the government is also in full support of achieving the SDGs, making them part of the strategies in the current Philippine Development Plan as well as in its MSME Development Plan. Policies, laws and regulations related to environmental protection and resource conservation (e.g., Renewable Energy Act, Biofuels Act, Clean Air Act, Mini-Hydroelectric Power Incentives Act, Clean Water Act, etc.) have been implemented to strengthen the country’s actions towards a greener growth. However, this is not the case in the cooperative sector. While there is the cooperative principle of “concern for community” that covers the environmental responsibility of a cooperative, such principle does not compel any cooperative to specifically integrate green practices in its operations nor legally apprehend it from not doing so.