Akihiko Hirasawa

Norinchukin Research Institute co., ltd

1-1-12, Uchikanda, Chiyoda-ku

Tokyo 101-0047 Japan

e-mail: akihiko@nochuri.co.jp

ABSTRACT

Land resource endowment, which is similar among monsoon Asian countries, and income levels are the main causes of uncompetitiveness in the agriculture of Japan. Uncompetitiveness, changes in diet, and trade liberalization were the main drivers of agricultural imports. The agricultural sector of Japan has specialized in land saving sectors such as livestock production that depended on imported feeds and horticulture, with the important exception of rice. Most sectors have lost the domestic market share significantly since trade liberalization.

Ongoing TPP negotiations can lead to further trade liberalization of sensitive agricultural products, unlike existing FTAs. Considering the previous experiences of liberalization and subsidy systems, it seems far from easy to maintain the level of domestic production with a compensation payment scheme.

Keywords: Direct Payment, Competitiveness, FTA, TPP, Compensation, Resource Endowment

INTRODUCTION

This article intends to offer an overview of agricultural import and domestic agricultural support in Japan in the context of trade liberalization. Such explanation requires some historical perspective as agricultural imports to Japan increased with economic development and gradual trade liberalization. In order to generalize and make it easier to share the experiences of Japan, the first part offers a general international perspective regarding competitiveness of agriculture and agricultural trade.

1. General Background for Monsoon Asian Countries

Principal determinants of competitiveness in agriculture

In general, resource endowment and technology are sources of international competitiveness (or comparative advantage). In the case of agriculture, the principal determinant is agricultural land resources (Deardroff 1984). Additionally, economic development affects agriculture in various ways including technology and consumption.

Effects of economic development

Through economic development, agriculture in land-scarce countries become even more uncompetitive due to the fact that other sectors grow more rapidly and the cost of labor and land increase. In such situations, countries tend to increase protection and subsidies to the agricultural sector.

At the same time, economic development leads to changes in diet. In particular, increased consumption of animal products and oil means that there is a need for additional land resources. In the case of land-scarce countries, this leads to a lack of enough agricultural land and expansion of import.

On top of these facts, trade liberalization further promotes dependence on imports. In actuality, uncompetitiveness, lack of enough land for agriculture, and trade liberalization were the main drivers of agricultural imports to Japan.

Arable land per capita in monsoon Asia

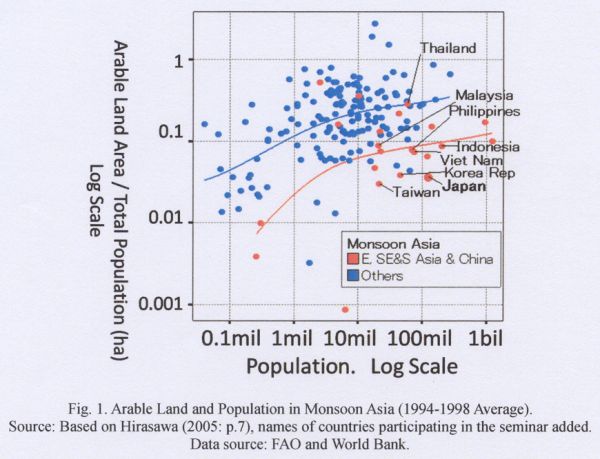

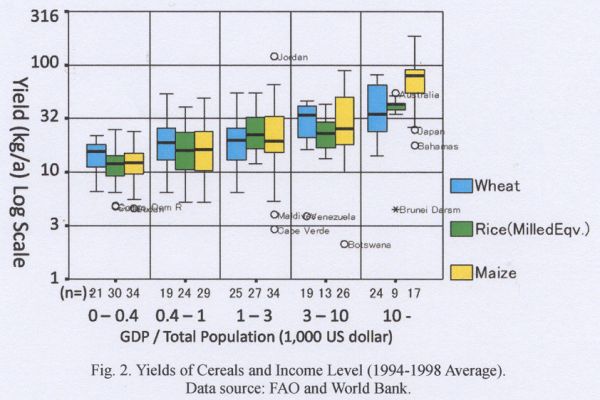

Countries in monsoon Asia tend to be land-scarce and heavily populated (Fig. 1). One of the common reasons for this is that rice production per unit area can feed more of the population than other cereals prior to the modernization of agriculture, which led to high population densities (Kyuma 1997). During the 20th century, modern agricultural technology enabled continuous cropping (on the same parcel every year) and high yields for cereals other than rice. International comparison of yields per unit area in the late 1990s among the three major cereals of the world (rice, wheat and maize) shows that economic development (GDP per capita), rather than species, explains the variance of the yield (Fig. 2). As a result, agriculture in monsoon Asian countries tends to be relatively less competitive because of the scarcity of agricultural land.

Cereals self sufficiency ratio (SSR)

The self-sufficiency ratio (SSR) is defined as the ratio of domestic production divided by domestic supply. SSR is a useful indicator of trade, as well as a summary of supply-demand balance. Because it is free from the effect of the scale of the country, it is suitable for international comparison. For the purpose of analysis from the point of view of calorie supply for countries, the SSR of cereals calculated based on weight is favorable because of its direct connection to land resources, importance as a staple food and feeds, and the availability and reliability of data.

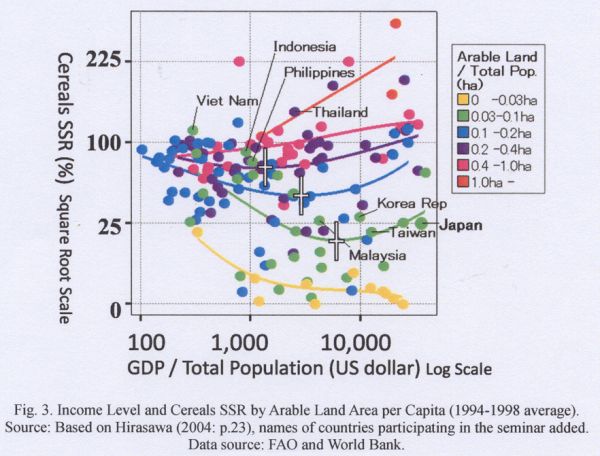

Fig. 3. shows the correlation between cereals SSR, arable land area per capita, and GDP per capita. The cereals SSR depends on arable land area per capita, while the variance of cereals SSR depends on GDP per capita. Countries with a lower GDP per capita tend to be more self-sufficient. Export is rather rare among the countries. The cereals SSR of countries with a higher GDP per capita tend to vary more, corresponding to arable land area per capita. That is to say, the specialization following comparative advantage from land resources tends to evolve with economic development.

This pattern is quite consistent although there seems to be some bias associated with rice production. Because paddy fields are relatively limited, rice producing countries can be competitive with less agricultural land per capita compared with upland cereal producing countries.

Agricultural support

The level of domestic agricultural support is higher in countries like Japan with higher income per capita and less competitive agriculture.

Empirically, the percentage PSE (the standard index of agricultural support including the gap between domestic and international prices) is mainly explained by GDP per capita and proxies of the competitiveness of agriculture - such as arable land per capita and agricultural trade indicators. The percentage PSE of Japan for cereals is in line with the international pattern described above (Hirasawa 2006).

2. Agricultural Trade Liberalization in Japan

Chronology of liberalization

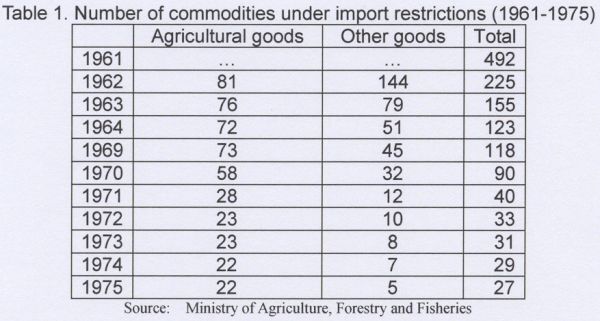

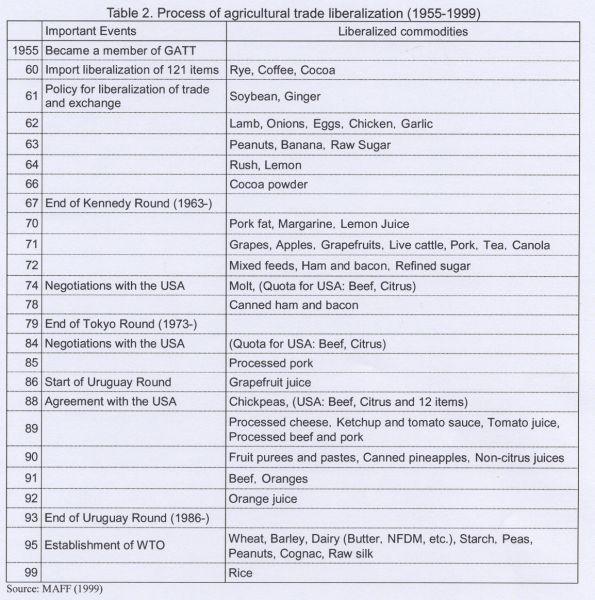

Since the 1960s, Japan has gradually liberalized imports of agricultural products through negotiations at the GATT rounds (Kennedy, Tokyo, and Uruguay) and negotiations with the USA (Tables 1 and 2). In 1962, there were 81 commodities under import restrictions. The number declined to 22 by 1974.

Soybeans and chickens were among the liberalized commodities in the early 1960s, pork in 1971 and, as a result of GATT dispute negotiations with the USA, beef and fruit juices (citrus and non-citrus) in the early 1990s.

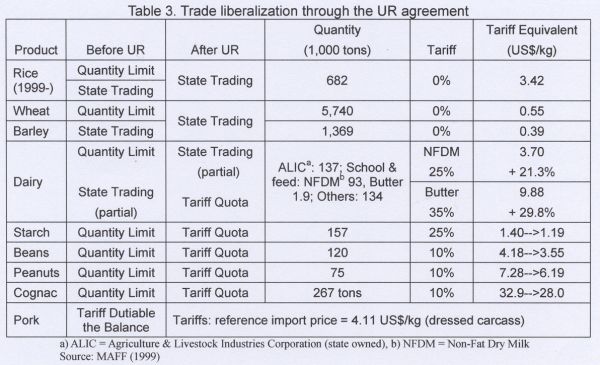

Remaining import restrictions were abolished through the implementation of the GATT UR agreement (Table 3). Imports of rice, wheat, dairy products such as butter and non-fat dry milk, were liberalized in the latter half of the 1990s. There were also tariff reductions for various items such as beef, oranges, orange juice, natural cheese, ice cream, candy, pasta, biscotti, soy and rapeseed oil.

Growth of imports

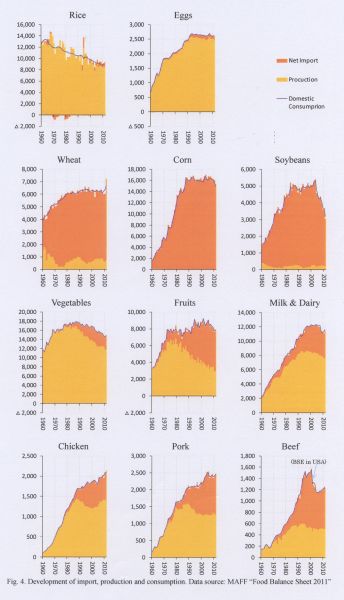

Following trade liberalization, in parallel with economic growth, agricultural imports increased significantly in various sectors (Fig. 4). The total self sufficiency ratio of food based on calories declined from 79% in 1960 to 39% in 2011. Among agricultural sectors, the following four patterns can be distinguished in development of supply and demand between the period of 1960 and 2011.

First, in the case of cereals (excluding rice) and oilseeds, domestic production is negligible to miniscule, and imports meet almost all of demand. As a result, imports increased in accordance with increase of demand. These imports filled the shortage of land resources in Japan to a substantial extent. There had been a tariff-free import scheme regarding corn as an animal feed ingredient.

Second, in the case of fruits, domestic production decreased significantly, and this decrease was substituted by imports. Vegetables show a similar trend, but the magnitude of substitution is smaller and consumption decreased. In both sectors, growth in domestic demand was limited or negative and subsidies were rather modest.

Third, in the case of animal meats (beef, pork and chicken) and dairy products, domestic production did not decrease much, while import increased to a large extent. In other words, import accounted for almost all of the growth in demand after a certain period of time, despite the capacity to increase domestic production by employing imported feeds.

Fourth, in the case of rice and eggs, imports have been quite limited. Rice, the only cereal with serious protection, faced a long continuing decline in demand. By contrast, the egg sector enjoyed an increase in demand until the early 1990s.

With respect to the evolution of imports quantity, the first pattern, as explained above, developed from the 1960s to the 1980s, as did the second and third patterns from the 1970s up until the present day.

Reliance on imports and specialization in production

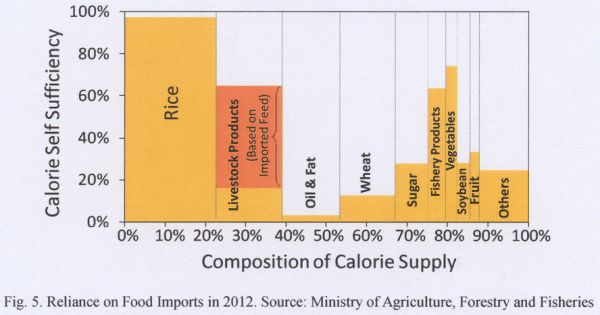

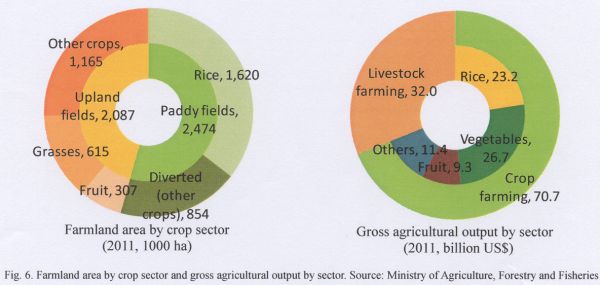

Faced with uncompetitiveness and lack of enough land resources, agriculture in Japan adapted the following ways (Fig. 5 and 6).

First, almost all land-intensive arable crops, such as cereals and oilseeds, were imported with the important exception of rice. Meanwhile, it also enabled the livestock and dairy sectors to grow rapidly, relying on imported feedstuffs.

Second, self-sufficiency in rice was maintained through high levels of border protection and subsidies. The justification for this is that rice is a staple food in the Japanese diet, well suited to the climate of Japan, and relatively not faced with severe competition from large agricultural exporting countries like the USA and Australia. Paddy fields constitute more than half of the farmland area (2011), although 34 % of the fields have been diverted to the other products due to a surplus.

Third, sectors such as dairy milk, eggs and vegetables mostly maintained their production levels. These sectors are less land intensive (given the imported feedstuffs) and more capital intensive. At the same time, transportation is relatively difficult or costly in these sectors.

As a result, the main components of agricultural gross output (2011) are livestock farming (30.9%), vegetables (25.9%), rice (22.4%) and fruits (9.0%). These sectors constitute 88.9% of agriculture as a whole. The trends described above can be considered as being reflective of the comparative disadvantages of Japan.

FTAs and RTAs

Until the 1990s, the foreign trade policy of Japan was quite GATT/WTO oriented. However, Japan changed its stance towards FTAs in the early 2000s (Table 4). In 2001, Japan started FTA negotiations with Singapore and signed an agreement in January 2002. Since then, Japan has adopted the FTA strategy (October 2002), the basic policy for the promotion of economic partnership agreement (December 2004), and the basic policy for comprehensive economic partnership (November 2011). There are currently 13 FTAs in effect. Eight are under negotiation, while another two are suspended or postponed, and one is being prepared for negotiation. In principle, sensitive agricultural products are excluded from further trade liberalization in existing FTAs.

Japan recently took another step towards regional trade agreements (RTAs), stimulated partly by the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement. Since the autumn of 2010, Japan has accelerated the consideration of participating in the TPP negotiations. Japan has existing FTAs with most of the countries participating in the TPP negotiations excluding Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the USA. All of these four countries are large exporters of agricultural products, while Japan had already started bilateral FTA negotiations with Australia and Canada by 2012. So from the perspective of the Japanese agricultural sector, it is not easy to have FTAs between Japan and the four countries. In fact, the negotiations with Australia remain unconcluded for more than six years. In 2013, negotiations for four significant FTAs started with the Republic of Korea and China (in March), the European Union (in April), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) (in May), and the TPP (in July), respectively.

3. Commodity Subsidies and the Case of Rice

Basic elements of commodity subsidies

Subsidy systems vary among different commodity sectors. However, essentially, many of them have some common functional features. The big picture of the subsidies system can be easier to understand from this perspective rather than describing the details of each subsidy.

First, there is a combined system composed of fixed rate payments and a “smoother,” which is usually compensation for decline in prices or revenue from the preceding periods. Arable crops and the dairy sector employ this type of subsidy. Vegetables (limited to 14 items grown in a designated region) sector have only a scheme similar to smoother.

Second, there is also a type of deficit payment, which is triggered when prices fall below a certain fixed level in order to fill the significant part of the gap. Beef calf, cattle, pork and egg sectors employ this type of subsidy.

Third, most of the subsidies listed above have a scheme where they are co-funded by farmers, making the subsidies similar to an insurance policy to some degree. In some cases, local governments (calf) or related industries (feed) also contribute to a portion of the fund. This scheme is typically applied to deficit payments and smoothers.

However, even with these measures, major agricultural sectors, with the exception of eggs, lost considerable share in the domestic market and could not expand domestic production following the trade liberalizations explained above.

Fixed rate payments and “smoothers”

A fixed rate payment is sometimes called “geta,” which means booster[1]. It usually intends to cover the average short fall of farm gate prices against production cost. The payment rates are based on a fixed rate per historical hectare (for most crops) or per unit weight (milk, sugar crops, starch crops). For some upland arable crops, there is an additional fixed rate payment per unit weight to encourage more production and quality improvement.

The smoother is sometimes called “narashi,” which means smoothing. It is compensation for a cyclical decline in prices or, in some cases, revenue. When the current price (or revenue) dips below the average of specific preceding periods (or period), most of the difference is compensated. The compound feed price stabilization system is similar to a smoother, though it is not compensation for a decline in prices but a mitigation of the increase in feed price for livestock farmers. For comparison, the Average Crop Revenue Election program in the USA is also a type of revenue smoother.

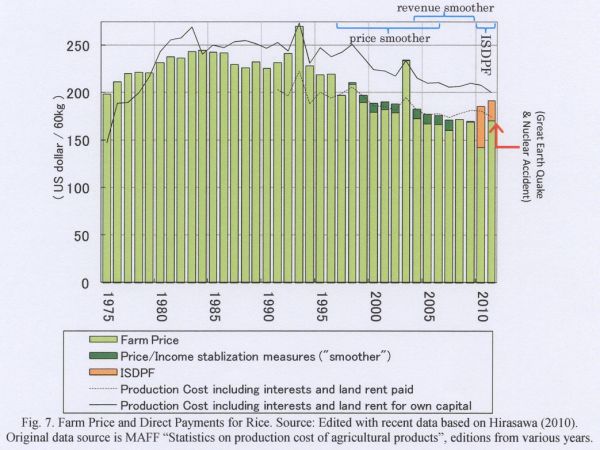

Smoothers for rice 1998-2009

Until 2009, there were only smoothers for rice and no fixed rate payments. In 1995, the price of rice was completely deregulated and administrative prices were abolished. This move enabled a reduction in AMS (Aggregate Measure of Support) to meet GATT UR commitments. Meanwhile, the downward trend in prices has accelerated since 1997 and a smoother scheme for rice was introduced in 1998. During the period between 1998 and 2006, there were price smoothers for all eligible farms. Between 2004 and 2006, there was an add-on revenue smoother only for large farms. These were later replaced by a “cross-commodity” revenue smoother in 2007, which offered compensation for declines in total revenue from major arable crops instead of individual revenues from each crop.

The main shortfall of the smoother is that it compensates decline in prices or revenue only over a rather short period (one to a few years). Because the payment is based on the difference between the current year price and the moving average price of the past few to several years, declines in prices (or revenue) over a long-term period are not compensated.

Since the mid-1980s, the downward trend of the price of rice continued for more than 20 years without significant compensation (Fig. 7). Throughout this period, the Japanese rice market was basically weak, given the large surplus of production capacity, shrinking domestic demand, and inability to export substantial amounts due to high prices.

The situation in Japan was quite different from that in the USA and EU, where the administrative support price for cereals remained. In the case of the USA and EU, cutting of support prices were compensated by direct payments in a broad sense, and such price cuts boosted export and/or domestic demand with the world price working as a price floor. The USA and EU are competitive and exporting countries of cereals. With reasonable subsidy outlays, they could narrow the gap between world prices and domestic production cost to an extent where it became suitable for export. This was not the case for Japan.

ISDPF: The newest scheme

The Income Support Direct Payment for Farmers (ISDPF) was introduced for rice in 2010. The ISDPF consists of a fixed portion and a variable portion, each of which is essentially a fixed rate payment and a price smoother, respectively. The fixed portion compensates permanent cost overruns and is based on the difference between standard production cost and past standard farm gate prices. The variable portion compensates residual cost overruns, if any, and is based on the excess of past standard production costs over current farm gate prices plus the fixed portion. The payment rates are uniform for all farmers nationwide.

In the first year of the ISDPF in 2010, rice prices fell by more than the payment rate of the fixed portion of the ISDPF. As a result, the drop triggered a payment of the variable portion with the same amount as the fixed portion. This meant the price drop canceled out most ISDPF payments. Without administrative prices and an adequate intervention purchasing system, it was difficult to stop the drop in prices. It was quite costly for the agricultural sector because the government provided the funds for the ISDPF through the reallocation of money from the other agricultural programs. The problem was that the price drop itself was caused by the very introduction of ISDPF.

In the USA and EU, there are debates over the capitalization of subsidies. Subsidies to farmers tend to trickle down to landowners through increases in land rents, leading to higher land prices. However, it seems rather difficult for this to happen in Japan as in many cases, landowners face a buyers market for agricultural land. Instead, a new subsidy can trickle down to downstream sectors in the form of discounts in farm gate prices, given the buyers market for rice and the strong bargaining strength of downstream sectors. In fact, according to Fujino (2011), the business margin of distributors had increased in the 2010 crop year, when imports of rice for food dipped by 86% because of drop in domestic price (Fujino 2013: p.39).

Since 2011, the long-term trend of falling prices had been interrupted. The supply-demand situation and prices changed in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake (March 11) and the subsequent severe accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Since this time, the price of rice grown in the northeast region has decreased due to the fear of radioactive contamination, while the price of old rice grown in the previous year as well as rice grown in western regions, to which consumer demand shifted in the retail market, increased.

Because the price of rice rebounded, the variable portion of the ISDPF was not triggered for the 2011 and 2012 crop years. Farmers in advantaged regions enjoyed high prices with fixed portion payments.

The ISDPF was extended to other major arable crops in 2011, but the structure of the ISDPF for these crops was different from rice and not changed radically from the previous ones. Besides, “cross-commodity” smoothers remained outside of the ISDPF. The future of the ISDPF is quite uncertain because the current administration (Liberal Democratic Party) wants to re-examine it, due to the fact that it was established by the previous administration (Democratic Party).

IMPLICATIONS AND DISCUSSION

FTAs, such as the TPP, with strong agricultural exporters have the potential to substantially reduce border protections in sensitive Japanese agricultural sectors. Given that domestic demand is saturated (expected to shrink because of demographic change) and export is negligible, further trade liberalizations logically mean an increase in imports and cutbacks in domestic production. In such case, some sort of compensation scheme will be needed. Unlike the WTO, FTAs usually do not restrict such domestic agricultural support measures.

However, the effectiveness of compensation measures is questionable. Even if a compensation payment that is consistent with production cost is introduced, the market share of domestic production is likely to drop as with previous cases in which competition with imports intensified and exports remained minimal.

Not to mention that the availability and sustainability of the budget funds for the compensation are uncertain. These compensation measures need additional funds, even though the government budget for the agricultural sector has basically shrunk for the past two decades. If some part of the fund is reallocated from other agricultural programs as in the case of the ISDPF for rice, it will be harmful for the agriculture sector. The measures have to comply with WTO concessions, which also restrict the amount of money to be employed.

On the other hand, the USA and EU successfully introduced direct payments for cereals to compensate for price reductions. This means payments with a justifiable budget largely narrowed the price gap between domestic and international markets, as well as reducing production surplus by stimulating export and/or domestic demand. They even abolished set-aside (supply control) during periods when the worldwide market was strong. In contrast, Japanese domestic farm gate prices of major crops are so high and isolated that they have not reacted to worldwide price hikes since 2007.

In the case of Japan, it is not realistic to expect a compensation that is enough to make Japanese agricultural products competitive in the international market. As a result, except in rare situations such as an extreme depreciation of the Japanese yen, it seems difficult to expand exports to a meaningful extent where it will have a significant impact on supply and demand.

In recent years some in the Japanese corporate community have advocated the export of agricultural products as a way to revitalize domestic agriculture. However, these arguments usually overlook fundamental factors such as land resource endowment and the size of country. As described above, most domestic products have been losing market share since trade liberalization. They are not very competitive even in the domestic market and too expensive to export in significant amounts.

Therefore, further trade liberalization should be minimized in order to maintain the scale of domestic agricultural production for the purpose of national food security, social safety net in rural regions, management of land resource, and other factors. In the case of liberalization, compensation payments should be financed by additional and sustainable funds for agriculture, even if they are not effective enough to avoid shrinkage of domestic production.

REFERENCES

Deardroff, Alan V. 1984. Testing Trade Theories and Predicting Trade Flows. Handbook of International Economics, vol. I, pp.467-517, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam.

Fujino, Nobuyuki. 2011. ISDPF Pilot Program for Rice and Change in Price Structure of Rice Among Trade Players. NRI Research Information, (24), May, Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Fujino, Nobuyuki. 2013. International Supply-Demand Situation of Rice and Self Sufficiency in Japan: Relating to Impact of TPP. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 66(1), pp.34-50, January, Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2004. Principal Determinants of Cereals Self-Sufficiency Ratio and Positioning of Japan: Cross-Country Analysis of Arable Land, Income, and Population Among 157 Countries. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 57(11), pp.14-33, Nov., Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2005. Disaggregation and Principal Determinants of Cereals Self-Sufficiency Ratio Among Countries in the World: A Comparison Based on Arable Land, Income, and Population of 157 Countries Including Japan. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 58(2), pp.70-97, Feb., Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2006. Relation Between Cereals Self-Sufficiency Ratio and Agricultural Support: Principal Factors Among 27 Countries Including Japan. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 59(1), pp.30-44, Jan., Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2010. Characteristics of, and Challenges for the ISDPF Program Compared with Western Countries: The Direct Payment System, Competitiveness, and Land Resources. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 63(12), pp.2-22, December, Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Kyuma, Kazutake. 1997. Food Production and Environment: Considering Sustainable Agriculture. (In Japanese)

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). 1999. Report on Trade of Agricultural Products. (In Japanese)

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). 2011. Food Balance Sheet 2011. (In Japanese)

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). Statistics on the Production Cost of Agricultural Products, Editions from Various Years. (In Japanese)

|

Submitted as a country paper for the FFTC-NACF International Seminar on Threats and Opportunities of the Free Trade Agreements in the Asian Region, Sept. 29 - Oct. 3, 2013. Seoul, Korea.

|

[1] "Geta" originally means a kind of wooden sandal in Japanese, with one or two protruding "teeth" on the underside. Because it "boosts" the height of the wearer, this is used as an analogy of boosting something up beyond itself.

Agricultural Imports, Trade Liberalization and Farm Income Supports in Japan

Akihiko Hirasawa

Norinchukin Research Institute co., ltd

1-1-12, Uchikanda, Chiyoda-ku

Tokyo 101-0047 Japan

e-mail: akihiko@nochuri.co.jp

ABSTRACT

Land resource endowment, which is similar among monsoon Asian countries, and income levels are the main causes of uncompetitiveness in the agriculture of Japan. Uncompetitiveness, changes in diet, and trade liberalization were the main drivers of agricultural imports. The agricultural sector of Japan has specialized in land saving sectors such as livestock production that depended on imported feeds and horticulture, with the important exception of rice. Most sectors have lost the domestic market share significantly since trade liberalization.

Ongoing TPP negotiations can lead to further trade liberalization of sensitive agricultural products, unlike existing FTAs. Considering the previous experiences of liberalization and subsidy systems, it seems far from easy to maintain the level of domestic production with a compensation payment scheme.

Keywords: Direct Payment, Competitiveness, FTA, TPP, Compensation, Resource Endowment

INTRODUCTION

This article intends to offer an overview of agricultural import and domestic agricultural support in Japan in the context of trade liberalization. Such explanation requires some historical perspective as agricultural imports to Japan increased with economic development and gradual trade liberalization. In order to generalize and make it easier to share the experiences of Japan, the first part offers a general international perspective regarding competitiveness of agriculture and agricultural trade.

1. General Background for Monsoon Asian Countries

Principal determinants of competitiveness in agriculture

In general, resource endowment and technology are sources of international competitiveness (or comparative advantage). In the case of agriculture, the principal determinant is agricultural land resources (Deardroff 1984). Additionally, economic development affects agriculture in various ways including technology and consumption.

Effects of economic development

Through economic development, agriculture in land-scarce countries become even more uncompetitive due to the fact that other sectors grow more rapidly and the cost of labor and land increase. In such situations, countries tend to increase protection and subsidies to the agricultural sector.

At the same time, economic development leads to changes in diet. In particular, increased consumption of animal products and oil means that there is a need for additional land resources. In the case of land-scarce countries, this leads to a lack of enough agricultural land and expansion of import.

On top of these facts, trade liberalization further promotes dependence on imports. In actuality, uncompetitiveness, lack of enough land for agriculture, and trade liberalization were the main drivers of agricultural imports to Japan.

Arable land per capita in monsoon Asia

Countries in monsoon Asia tend to be land-scarce and heavily populated (Fig. 1). One of the common reasons for this is that rice production per unit area can feed more of the population than other cereals prior to the modernization of agriculture, which led to high population densities (Kyuma 1997). During the 20th century, modern agricultural technology enabled continuous cropping (on the same parcel every year) and high yields for cereals other than rice. International comparison of yields per unit area in the late 1990s among the three major cereals of the world (rice, wheat and maize) shows that economic development (GDP per capita), rather than species, explains the variance of the yield (Fig. 2). As a result, agriculture in monsoon Asian countries tends to be relatively less competitive because of the scarcity of agricultural land.

Cereals self sufficiency ratio (SSR)

The self-sufficiency ratio (SSR) is defined as the ratio of domestic production divided by domestic supply. SSR is a useful indicator of trade, as well as a summary of supply-demand balance. Because it is free from the effect of the scale of the country, it is suitable for international comparison. For the purpose of analysis from the point of view of calorie supply for countries, the SSR of cereals calculated based on weight is favorable because of its direct connection to land resources, importance as a staple food and feeds, and the availability and reliability of data.

Fig. 3. shows the correlation between cereals SSR, arable land area per capita, and GDP per capita. The cereals SSR depends on arable land area per capita, while the variance of cereals SSR depends on GDP per capita. Countries with a lower GDP per capita tend to be more self-sufficient. Export is rather rare among the countries. The cereals SSR of countries with a higher GDP per capita tend to vary more, corresponding to arable land area per capita. That is to say, the specialization following comparative advantage from land resources tends to evolve with economic development.

This pattern is quite consistent although there seems to be some bias associated with rice production. Because paddy fields are relatively limited, rice producing countries can be competitive with less agricultural land per capita compared with upland cereal producing countries.

Agricultural support

The level of domestic agricultural support is higher in countries like Japan with higher income per capita and less competitive agriculture.

Empirically, the percentage PSE (the standard index of agricultural support including the gap between domestic and international prices) is mainly explained by GDP per capita and proxies of the competitiveness of agriculture - such as arable land per capita and agricultural trade indicators. The percentage PSE of Japan for cereals is in line with the international pattern described above (Hirasawa 2006).

2. Agricultural Trade Liberalization in Japan

Chronology of liberalization

Since the 1960s, Japan has gradually liberalized imports of agricultural products through negotiations at the GATT rounds (Kennedy, Tokyo, and Uruguay) and negotiations with the USA (Tables 1 and 2). In 1962, there were 81 commodities under import restrictions. The number declined to 22 by 1974.

Soybeans and chickens were among the liberalized commodities in the early 1960s, pork in 1971 and, as a result of GATT dispute negotiations with the USA, beef and fruit juices (citrus and non-citrus) in the early 1990s.

Remaining import restrictions were abolished through the implementation of the GATT UR agreement (Table 3). Imports of rice, wheat, dairy products such as butter and non-fat dry milk, were liberalized in the latter half of the 1990s. There were also tariff reductions for various items such as beef, oranges, orange juice, natural cheese, ice cream, candy, pasta, biscotti, soy and rapeseed oil.

Growth of imports

Following trade liberalization, in parallel with economic growth, agricultural imports increased significantly in various sectors (Fig. 4). The total self sufficiency ratio of food based on calories declined from 79% in 1960 to 39% in 2011. Among agricultural sectors, the following four patterns can be distinguished in development of supply and demand between the period of 1960 and 2011.

First, in the case of cereals (excluding rice) and oilseeds, domestic production is negligible to miniscule, and imports meet almost all of demand. As a result, imports increased in accordance with increase of demand. These imports filled the shortage of land resources in Japan to a substantial extent. There had been a tariff-free import scheme regarding corn as an animal feed ingredient.

Second, in the case of fruits, domestic production decreased significantly, and this decrease was substituted by imports. Vegetables show a similar trend, but the magnitude of substitution is smaller and consumption decreased. In both sectors, growth in domestic demand was limited or negative and subsidies were rather modest.

Third, in the case of animal meats (beef, pork and chicken) and dairy products, domestic production did not decrease much, while import increased to a large extent. In other words, import accounted for almost all of the growth in demand after a certain period of time, despite the capacity to increase domestic production by employing imported feeds.

Fourth, in the case of rice and eggs, imports have been quite limited. Rice, the only cereal with serious protection, faced a long continuing decline in demand. By contrast, the egg sector enjoyed an increase in demand until the early 1990s.

With respect to the evolution of imports quantity, the first pattern, as explained above, developed from the 1960s to the 1980s, as did the second and third patterns from the 1970s up until the present day.

Reliance on imports and specialization in production

Faced with uncompetitiveness and lack of enough land resources, agriculture in Japan adapted the following ways (Fig. 5 and 6).

First, almost all land-intensive arable crops, such as cereals and oilseeds, were imported with the important exception of rice. Meanwhile, it also enabled the livestock and dairy sectors to grow rapidly, relying on imported feedstuffs.

Second, self-sufficiency in rice was maintained through high levels of border protection and subsidies. The justification for this is that rice is a staple food in the Japanese diet, well suited to the climate of Japan, and relatively not faced with severe competition from large agricultural exporting countries like the USA and Australia. Paddy fields constitute more than half of the farmland area (2011), although 34 % of the fields have been diverted to the other products due to a surplus.

Third, sectors such as dairy milk, eggs and vegetables mostly maintained their production levels. These sectors are less land intensive (given the imported feedstuffs) and more capital intensive. At the same time, transportation is relatively difficult or costly in these sectors.

As a result, the main components of agricultural gross output (2011) are livestock farming (30.9%), vegetables (25.9%), rice (22.4%) and fruits (9.0%). These sectors constitute 88.9% of agriculture as a whole. The trends described above can be considered as being reflective of the comparative disadvantages of Japan.

FTAs and RTAs

Until the 1990s, the foreign trade policy of Japan was quite GATT/WTO oriented. However, Japan changed its stance towards FTAs in the early 2000s (Table 4). In 2001, Japan started FTA negotiations with Singapore and signed an agreement in January 2002. Since then, Japan has adopted the FTA strategy (October 2002), the basic policy for the promotion of economic partnership agreement (December 2004), and the basic policy for comprehensive economic partnership (November 2011). There are currently 13 FTAs in effect. Eight are under negotiation, while another two are suspended or postponed, and one is being prepared for negotiation. In principle, sensitive agricultural products are excluded from further trade liberalization in existing FTAs.

Japan recently took another step towards regional trade agreements (RTAs), stimulated partly by the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement. Since the autumn of 2010, Japan has accelerated the consideration of participating in the TPP negotiations. Japan has existing FTAs with most of the countries participating in the TPP negotiations excluding Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the USA. All of these four countries are large exporters of agricultural products, while Japan had already started bilateral FTA negotiations with Australia and Canada by 2012. So from the perspective of the Japanese agricultural sector, it is not easy to have FTAs between Japan and the four countries. In fact, the negotiations with Australia remain unconcluded for more than six years. In 2013, negotiations for four significant FTAs started with the Republic of Korea and China (in March), the European Union (in April), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) (in May), and the TPP (in July), respectively.

3. Commodity Subsidies and the Case of Rice

Basic elements of commodity subsidies

Subsidy systems vary among different commodity sectors. However, essentially, many of them have some common functional features. The big picture of the subsidies system can be easier to understand from this perspective rather than describing the details of each subsidy.

First, there is a combined system composed of fixed rate payments and a “smoother,” which is usually compensation for decline in prices or revenue from the preceding periods. Arable crops and the dairy sector employ this type of subsidy. Vegetables (limited to 14 items grown in a designated region) sector have only a scheme similar to smoother.

Second, there is also a type of deficit payment, which is triggered when prices fall below a certain fixed level in order to fill the significant part of the gap. Beef calf, cattle, pork and egg sectors employ this type of subsidy.

Third, most of the subsidies listed above have a scheme where they are co-funded by farmers, making the subsidies similar to an insurance policy to some degree. In some cases, local governments (calf) or related industries (feed) also contribute to a portion of the fund. This scheme is typically applied to deficit payments and smoothers.

However, even with these measures, major agricultural sectors, with the exception of eggs, lost considerable share in the domestic market and could not expand domestic production following the trade liberalizations explained above.

Fixed rate payments and “smoothers”

A fixed rate payment is sometimes called “geta,” which means booster[1]. It usually intends to cover the average short fall of farm gate prices against production cost. The payment rates are based on a fixed rate per historical hectare (for most crops) or per unit weight (milk, sugar crops, starch crops). For some upland arable crops, there is an additional fixed rate payment per unit weight to encourage more production and quality improvement.

The smoother is sometimes called “narashi,” which means smoothing. It is compensation for a cyclical decline in prices or, in some cases, revenue. When the current price (or revenue) dips below the average of specific preceding periods (or period), most of the difference is compensated. The compound feed price stabilization system is similar to a smoother, though it is not compensation for a decline in prices but a mitigation of the increase in feed price for livestock farmers. For comparison, the Average Crop Revenue Election program in the USA is also a type of revenue smoother.

Smoothers for rice 1998-2009

Until 2009, there were only smoothers for rice and no fixed rate payments. In 1995, the price of rice was completely deregulated and administrative prices were abolished. This move enabled a reduction in AMS (Aggregate Measure of Support) to meet GATT UR commitments. Meanwhile, the downward trend in prices has accelerated since 1997 and a smoother scheme for rice was introduced in 1998. During the period between 1998 and 2006, there were price smoothers for all eligible farms. Between 2004 and 2006, there was an add-on revenue smoother only for large farms. These were later replaced by a “cross-commodity” revenue smoother in 2007, which offered compensation for declines in total revenue from major arable crops instead of individual revenues from each crop.

The main shortfall of the smoother is that it compensates decline in prices or revenue only over a rather short period (one to a few years). Because the payment is based on the difference between the current year price and the moving average price of the past few to several years, declines in prices (or revenue) over a long-term period are not compensated.

Since the mid-1980s, the downward trend of the price of rice continued for more than 20 years without significant compensation (Fig. 7). Throughout this period, the Japanese rice market was basically weak, given the large surplus of production capacity, shrinking domestic demand, and inability to export substantial amounts due to high prices.

The situation in Japan was quite different from that in the USA and EU, where the administrative support price for cereals remained. In the case of the USA and EU, cutting of support prices were compensated by direct payments in a broad sense, and such price cuts boosted export and/or domestic demand with the world price working as a price floor. The USA and EU are competitive and exporting countries of cereals. With reasonable subsidy outlays, they could narrow the gap between world prices and domestic production cost to an extent where it became suitable for export. This was not the case for Japan.

ISDPF: The newest scheme

The Income Support Direct Payment for Farmers (ISDPF) was introduced for rice in 2010. The ISDPF consists of a fixed portion and a variable portion, each of which is essentially a fixed rate payment and a price smoother, respectively. The fixed portion compensates permanent cost overruns and is based on the difference between standard production cost and past standard farm gate prices. The variable portion compensates residual cost overruns, if any, and is based on the excess of past standard production costs over current farm gate prices plus the fixed portion. The payment rates are uniform for all farmers nationwide.

In the first year of the ISDPF in 2010, rice prices fell by more than the payment rate of the fixed portion of the ISDPF. As a result, the drop triggered a payment of the variable portion with the same amount as the fixed portion. This meant the price drop canceled out most ISDPF payments. Without administrative prices and an adequate intervention purchasing system, it was difficult to stop the drop in prices. It was quite costly for the agricultural sector because the government provided the funds for the ISDPF through the reallocation of money from the other agricultural programs. The problem was that the price drop itself was caused by the very introduction of ISDPF.

In the USA and EU, there are debates over the capitalization of subsidies. Subsidies to farmers tend to trickle down to landowners through increases in land rents, leading to higher land prices. However, it seems rather difficult for this to happen in Japan as in many cases, landowners face a buyers market for agricultural land. Instead, a new subsidy can trickle down to downstream sectors in the form of discounts in farm gate prices, given the buyers market for rice and the strong bargaining strength of downstream sectors. In fact, according to Fujino (2011), the business margin of distributors had increased in the 2010 crop year, when imports of rice for food dipped by 86% because of drop in domestic price (Fujino 2013: p.39).

Since 2011, the long-term trend of falling prices had been interrupted. The supply-demand situation and prices changed in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake (March 11) and the subsequent severe accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Since this time, the price of rice grown in the northeast region has decreased due to the fear of radioactive contamination, while the price of old rice grown in the previous year as well as rice grown in western regions, to which consumer demand shifted in the retail market, increased.

Because the price of rice rebounded, the variable portion of the ISDPF was not triggered for the 2011 and 2012 crop years. Farmers in advantaged regions enjoyed high prices with fixed portion payments.

The ISDPF was extended to other major arable crops in 2011, but the structure of the ISDPF for these crops was different from rice and not changed radically from the previous ones. Besides, “cross-commodity” smoothers remained outside of the ISDPF. The future of the ISDPF is quite uncertain because the current administration (Liberal Democratic Party) wants to re-examine it, due to the fact that it was established by the previous administration (Democratic Party).

IMPLICATIONS AND DISCUSSION

FTAs, such as the TPP, with strong agricultural exporters have the potential to substantially reduce border protections in sensitive Japanese agricultural sectors. Given that domestic demand is saturated (expected to shrink because of demographic change) and export is negligible, further trade liberalizations logically mean an increase in imports and cutbacks in domestic production. In such case, some sort of compensation scheme will be needed. Unlike the WTO, FTAs usually do not restrict such domestic agricultural support measures.

However, the effectiveness of compensation measures is questionable. Even if a compensation payment that is consistent with production cost is introduced, the market share of domestic production is likely to drop as with previous cases in which competition with imports intensified and exports remained minimal.

Not to mention that the availability and sustainability of the budget funds for the compensation are uncertain. These compensation measures need additional funds, even though the government budget for the agricultural sector has basically shrunk for the past two decades. If some part of the fund is reallocated from other agricultural programs as in the case of the ISDPF for rice, it will be harmful for the agriculture sector. The measures have to comply with WTO concessions, which also restrict the amount of money to be employed.

On the other hand, the USA and EU successfully introduced direct payments for cereals to compensate for price reductions. This means payments with a justifiable budget largely narrowed the price gap between domestic and international markets, as well as reducing production surplus by stimulating export and/or domestic demand. They even abolished set-aside (supply control) during periods when the worldwide market was strong. In contrast, Japanese domestic farm gate prices of major crops are so high and isolated that they have not reacted to worldwide price hikes since 2007.

In the case of Japan, it is not realistic to expect a compensation that is enough to make Japanese agricultural products competitive in the international market. As a result, except in rare situations such as an extreme depreciation of the Japanese yen, it seems difficult to expand exports to a meaningful extent where it will have a significant impact on supply and demand.

In recent years some in the Japanese corporate community have advocated the export of agricultural products as a way to revitalize domestic agriculture. However, these arguments usually overlook fundamental factors such as land resource endowment and the size of country. As described above, most domestic products have been losing market share since trade liberalization. They are not very competitive even in the domestic market and too expensive to export in significant amounts.

Therefore, further trade liberalization should be minimized in order to maintain the scale of domestic agricultural production for the purpose of national food security, social safety net in rural regions, management of land resource, and other factors. In the case of liberalization, compensation payments should be financed by additional and sustainable funds for agriculture, even if they are not effective enough to avoid shrinkage of domestic production.

REFERENCES

Deardroff, Alan V. 1984. Testing Trade Theories and Predicting Trade Flows. Handbook of International Economics, vol. I, pp.467-517, Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam.

Fujino, Nobuyuki. 2011. ISDPF Pilot Program for Rice and Change in Price Structure of Rice Among Trade Players. NRI Research Information, (24), May, Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Fujino, Nobuyuki. 2013. International Supply-Demand Situation of Rice and Self Sufficiency in Japan: Relating to Impact of TPP. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 66(1), pp.34-50, January, Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2004. Principal Determinants of Cereals Self-Sufficiency Ratio and Positioning of Japan: Cross-Country Analysis of Arable Land, Income, and Population Among 157 Countries. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 57(11), pp.14-33, Nov., Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2005. Disaggregation and Principal Determinants of Cereals Self-Sufficiency Ratio Among Countries in the World: A Comparison Based on Arable Land, Income, and Population of 157 Countries Including Japan. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 58(2), pp.70-97, Feb., Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2006. Relation Between Cereals Self-Sufficiency Ratio and Agricultural Support: Principal Factors Among 27 Countries Including Japan. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 59(1), pp.30-44, Jan., Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Hirasawa, Akihiko. 2010. Characteristics of, and Challenges for the ISDPF Program Compared with Western Countries: The Direct Payment System, Competitiveness, and Land Resources. Monthly Review of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Finance, 63(12), pp.2-22, December, Norinchukin Research Institute. (In Japanese)

Kyuma, Kazutake. 1997. Food Production and Environment: Considering Sustainable Agriculture. (In Japanese)

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). 1999. Report on Trade of Agricultural Products. (In Japanese)

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). 2011. Food Balance Sheet 2011. (In Japanese)

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). Statistics on the Production Cost of Agricultural Products, Editions from Various Years. (In Japanese)

Submitted as a country paper for the FFTC-NACF International Seminar on Threats and Opportunities of the Free Trade Agreements in the Asian Region, Sept. 29 - Oct. 3, 2013. Seoul, Korea.

[1] "Geta" originally means a kind of wooden sandal in Japanese, with one or two protruding "teeth" on the underside. Because it "boosts" the height of the wearer, this is used as an analogy of boosting something up beyond itself.