Jiun-Hao Wang

Associate Professor

Department of Bio-industry Communication and Development,

National Taiwan University

No 1, Roosevelt Rd, Sec 4, Taipei 10617, Taiwan

E-mail: wangjh@ntu.edu.tw

ABSTRACT

The small-scale agricultural countries encounter severe structural problems, particularly the rapid ageing of the farmer population and the scarcity of young farmers entering the profession. Determining how to support young farmers is a political priority for the future agricultural policy regarding the small-holding farming world. Given that setting up young farmers has been at the centre of the common agricultural policy in the EU since the 1980s. This article takes the European experience as an example to systematically review current young farmers schemes (YFS). The main objective of this article is to propose a policy framework for recruiting young farmers by systematically reviewing the current supporting measures for young farmers. Result shows that the inheritance from an older family member is the most favorable and most feasible way to recruit young farmers among other entry channels set up farm business. Moreover, the installation aid for young farmers and the early retirement scheme are regarded as coupled instruments on promoting intergenerational farm transfer. However, successfully recruiting young farmers to join small-scale farming is necessary to further employ other supplementary measures, including farm improvement scheme, agricultural extension service, farm succession advice, tax reduction within installation period. Consequently, considering the limitation of farming returns in small holdings, diversifying rural economic activity in the form of supporting non-agricultural new businesses might be an alternative approach for setting up next generational entrepreneurs in the countryside.

Key words: Agricultural structure, Family farm, Generational renewal, Young farmers scheme, Early retirement scheme

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural restructuring is regarded as an important policy issue in the smallholder agriculture countries. The small-scale farming system encounters severe structural problems, particularly the rapid ageing of the farmer population and the scarcity of young farmers entering the profession. The consequences of unsolved structural problems will hamper sustainable agricultural development (Ilbery, Chiotti and Rickard, 1997). For example, the number of young farmers involved in European agriculture is falling fast. With continuously decreasing numbers of European farmers less than 35 years of age, while one-quarter are over 65, effective measures are needed to encourage new entrants into the agricultural sector (European Communities, 2012). The demographic aging problem is more severe in Asian countries than in the EU (Oizumi, Kajiwara and Aratame, 2006).

The age-related structural crisis will lead to an array of agricultural development problems; in particular, farm productivity, market competitiveness, rural economic viability and food security will be under threat. These challenges related to the lack of generational renewal in the farming system should be overcome to secure agricultural sustainability. Therefore, determining how to support young farmers is a political priority for the future agricultural policy regarding the small-holding farming world (Hazell, Poulton, Wiggins and Dorward, 2007).

Unlike market management tools, structural measures have the potential to directly affect farmland consolidation, farm holdings improvement, enlargement of farm size, generational renewal of family farms, young farmer training, early retirement and the adjustment of less developed, less densely populated rural areas, (Gibbard, 1997). However, the policy objectives of maintaining an efficient and prosperous small-scale farm sector are still facing several problems; for example, over-priced farmland results in high entry costs for entering into farming.

Previous studies indicate that, compared to their older counterparts, young farmers have more potential to improve farm competitiveness and achieve better social viability for rural communities. Moreover, young farmers can also promote a wider range of rural socio-economic activities, such as food safety, rural tourism, conservation of traditions and cultural heritage, awareness of the negative effects of farmland abandonment, and participation in local associations (Bryant and Gray, 2005; European Communities, 2012). Therefore, the renewal of farming generations has become an urgent need for the adjustment of the agricultural sector.

Although a growing body of literature has discussed the policy tools required to recruit young farmers into small-scale farming (Quendler, 2012; FAO, 2014), relatively little attention has been paid to the generational renewal of family farming.To fill this knowledge gap, this article takes the European Union (EU) experience as an example to systematically review current young farmers schemes (YFS). The objective of this article is threefold: exploring the structural changes and challenges of small-scale agriculture, discussing the entry obstacles and possible channels for new farmers, and finally proposing a policy framework for recruiting young farmers by systematically reviewing the current supporting measures for young farmers.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The next section briefly introduces the structural changes and challenges of small-scale agriculture. Section 3 discusses the entry obstacles and possible channels for new farmers. This is followed in Section 4 by a systematic review of the existing policy instruments to support young farmers. This article then proposes a conceptual framework for recruiting young farmers under the structural perspective in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes this article with a brief summary and a discussion on policy implications.

CHANGES AND CHALLENGES OF SMALL-SCALE AGRICULTURAL STRUCTURE

The structural changes in land ownership, farm size and age composition of farmers have been understood to have a significant impact on the efficient use of agricultural resources (de Janvry et al., 2001). The agricultural structural policy aims to reallocate resources to those producers with better capability of maximizing farm productivity and profitability. A particular structural challenge concerns the future development of family farms (Davidova et al. 2013; Tropea, 2014). According to the Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) definition, “family farm is an agricultural holding which is managed and operated by a household and where farm labor is largely supplied by that household” (FAO, 2013).

Davidova and Thomson (2013) indicate that family farming is synonymous with small, semi-subsistence farms. Indeed, family farming is the most common business model in small-scale agriculture. On the contrary, large incorporated farms account for only a small proportion of the global farm system. Given that the unique and substantial contribution of family farms to the production of food and public goods, as well as ensuring balanced rural development, the FAO has designated 2014 as the “International Year of the Family Farm” (Tropea, 2014).

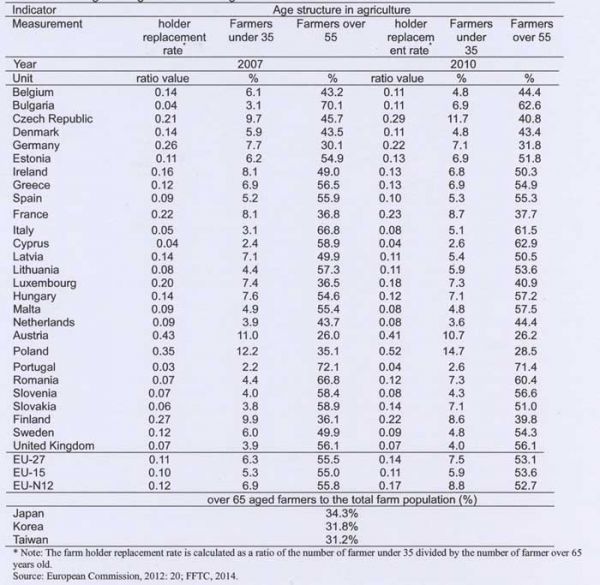

The main challenges faced by family farms are illustrated by two features. First, the changing demographic structure of family farm is facing a serious aging challenge. Take the European agricultural sector for example; over 97 percent of Europe’s farms are family-based business. However, only 7 percent of the farmers in the EU-27 are under the age of 35, and nearly 24.5% of farmers are aged 65 or more, see Table 1 (European Communities, 2012). The aging problem of small-scale agriculture is more serious in Asian countries: the percentage of the aged over 65 farmers to the total farm population are 34.3%, 31.8% and 31.2% for Japan, Korea, Taiwan in Taiwan, respectively (FFTC, 2014).

Given that the generational renewal is essential to the sustainability of family farming, the structural policy should put more efforts into “getting old farmers out” in a suitable manner, as well as “recruiting young people into farming” in a way that is competitive and productive in the long-term (Tropea, 2014). Despite its predominance in the agricultural structure, family farming encounters several difficulties in remaining economically viable, such as expensive land cost, low farm efficiency and productivity, high input prices, lacking accessibility of credit or other financial resources, weak bargaining power within the supply chain, fluctuating market prices and being particularly vulnerable to climate change (European Commission, 2012).

The above mentioned challenges can also be identified as the barriers for young people to enter into farming, especially the relatively scarce, as well as expensive land, and the limited access to credit. Therefore, entry to farming through means other than inheritance is difficult in family farming system. It is acknowledged that generational renewal is a major element in the replication of family farming. However, intergenerational transfer is not only about “getting old farmers out” and “establishing new farmers”, but also concerns the transfer of farm proprietary rights and household livelihood security between generations (Tropea, 2014).

Table 1. Changes of age structure in agriculture in the EU

ENTRY OBSTACLES AND POSSIBLE CHANNELS FOR YOUNG FARMERS

The steady decline in the number of family farms has led to a significant shortage of new farmers. Most small-scale agriculture countries are consequently faced with a dual problem: the scarcity of young farmers and the rapid ageing of the farmer population. The severity of the structural situation can be grasped by using the farm holder replacement rate, i.e. the number of holders under 35 divided by the number of holders over 55 (Regidor, 2012; (European Communities, 2012). Therefore, the answer to achieving structural improvement lies in the support offered young people to become more willing to choose the career of farming.

Essentially, agricultural work is regarded as a 3D job (namely dirty, dangerous and difficult) which is in contrast to white-collar work with higher income (Osawa, 2014). Thus it is difficult to recruiting young people to enter into farming. Moreover, three main causes for new entrants to farming decision should be taken into consideration: farm productivity and profitability, volume of employment generated and the ability to earn a satisfactory livelihood (Regidor, 2012); these three factors may become major obstacles to running a small-scale holding.

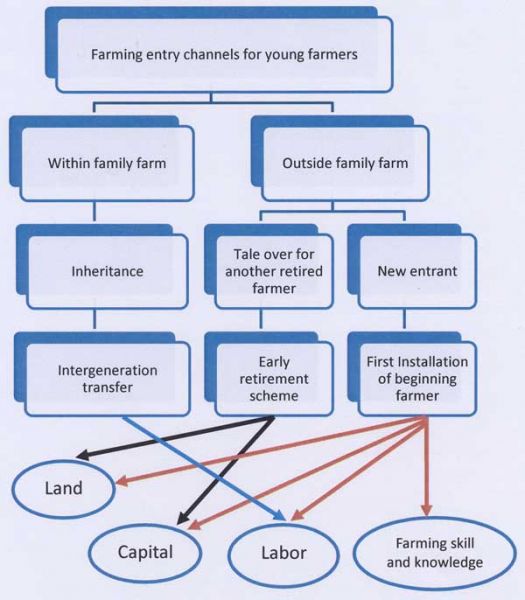

There are three possible entry channels for young farmers to set up business: (a) family inheritance; (2) taking over from other retiring farmers (related to early retirement scheme); and (3) first installation of farming (for the beginning farmer or new entrant). With the predominance of family farming in small-scale agriculture, the inheritance from an older family member is the most favorable and most feasible way to recruit young farmers among these channels (Sotte, 2003; Quendler, 2012; Regidor, 2012).

Moreover, the early retirement scheme uses a subsidy measure designed to encourage older farmers to retire early, and is awarded when agricultural holdings are transferred to young entrants. Hence, the early retirement scheme is also a useful instrument to accelerate generational renewal outside the family farm. The last channel, from the beginning to entry farming, is particularly difficult for young people to engage in farming career. Accessing affordable land and capital plays a critical role for beginners to establish their farm. Furthermore, the high price and limited land market poses a significant barrier to new entrants and to expanding young farms.

A large body of literature has shown that many young farmers are credit constrained; this demonstrates negative consequences for farm development (Swinnen and Gow, 1999; Davidova et al. 2013). Gaining accessibility to credit is widely acknowledged as a major challenge facing young farmers attempting to establish, enlarge, invest in, or modernize their businesses. Most current schemes targeting young farmers aim to encourage those who are under 40 years of age to choose a farming career, by providing financial support measures. However, different entry channels require specific support mechanisms and requirements; the eligibility for the various YFS measures is conditioned by the entry channel voluntarily or obligatorily adopted by young farmers.

From the agricultural structural perspective, farm inheritance is the optimal channel for the family farming structure. The measures needed to constitute an incentive package for the family successors include young farmer start-up aid and farm holding improvement. In addition, the government should provide succession planning advice to facilitate the successful transfer from one generation to another. In contrast, another entry channel is via older farmer's retirement; the supporting measures should take the transfer process into account, namely the early retirement payment. Lastly, in addition to young farmer start-up aid, for the entry channel for new beginning farmers, the supporting measures should pay more attention to land acquisition and provision of training programs on vocational skills and farming knowledge (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Entry channels for young farmers to set up farm holding.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF SUPPORT MEASURES FOR YOUNG FARMERS: A STRUCTURAL PERSPECTIVE

According to the entry channels to set up farm business, different types of young farmers can be divided into three categories: farm succession within the family through inheritance, farm succession outside the family by taking over from other retiring farmers and new entrants to farming (i.e. the beginning farmer). In general, the land, labor, capital, and farming skills and ability are important input factors for the young farmers to start-up a holding. However, the needs and challenges facing young farmers are diverse, differing by entry channel, farm size and available resources. Hence designing comprehensive and effective policies to support young farmers is problematic.

Support for young people entering into farming has been at the centre of the common agricultural policy (CAP) in the EU since the 1980s. This article will take the CAP experience as an example to illustrate the possible policy instrument for setting up young farmers, and will lead to further discussion. For setting up a new farm holding, the major challenges lie in high costs for farm investments in the initial establishment stage; accessing affordable land and credit is critical to the start-up process (Gibbard, 1997). Therefore, the CAP provides different financial measures for setting up young farmer; they aim at enhancing farm management by renewing the manager generation, encouraging young farmers to invest in farm modernization, and improving the management practices and performances relate to the agricultural holding.

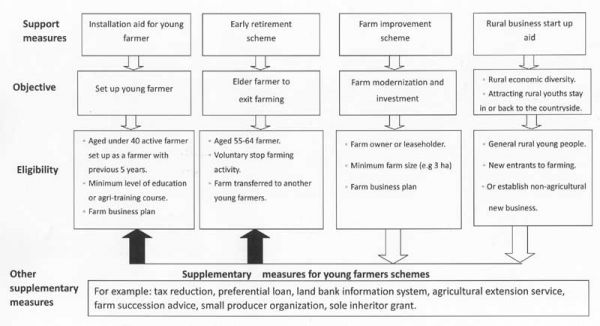

Reviewing the young farmers schemes, which has been implemented in the EU, the existing YFS measures can be classified into three categories, as follows (see Figure 2) (Regidor, 2012; Tropea, 2014):

-

Installation aid for young farmers: measures providing access to maximum setting up subsidies for young farmers (set up as a farmer within the previous five years) to establish their own holdings, such as an up-limited single payment of total investment, preferential loans and/or plus interest subsidy. Such subsidies have been available to young farmers in the form of special aid payments for their first installation of farming. In addition to age requirement (under 40 years), the eligibility for payment entitlements is usually subject to attaining a minimum level of education or participating in certain agricultural training courses, as well as offering a business plan. The requirement to submit and implement a business plan is likely to contribute to improving the competitiveness of farm holdings (Tropea, 2014).

-

Early retirement scheme: measures that encourage elderly farmers (aged between 55 and 64) to transfer their holdings to qualified young farmers by providing them with an annual fixed pension payment; for instance, be eligible for a pension of up to €15,000 a year for up to 10 years in Ireland (Caskie et al., 2002; Regidor, 2012). It is evident that such early retirement schemes have been successful in encouraging retirement and replacing older farmers with younger or more productive farmers, and in increasing the average size of farm holding at the same time (Scanlan, 2002; Matthews, 2013).

-

Farm improvement scheme: subsidy measures that provide special support for farmers to invest in farm modernization, particularly in regard to obtaining access to land. This measure will complement the installation aid for young farmers by subjecting eligibility to compliance with the business plan requirement.

Figure 2. Policy framework for young farmers scheme and supplementary measures.

In addition to financial subsidy measures, offering tax incentives, creating a convenient and affordable land tenure system, providing farm advice services and training programs, as well as promoting cooperatives and producer organizations are also relevant accompanying policy tools to assist smaller-scale young farmers to start up and promote their farming career (Hill and Blanford, 2007; Tropea, 2014). For example, agricultural training and education courses are important for young farmers to develop their farm businesses. Similarly, the farm advisory services offering business operation and investment appraisal advice would help to ensure progressive productivity through the efforts of young farmers. Both of these agricultural extension programs place considerable emphasis on knowledge transfer and innovation, which allow them to adopt new technologies on their farms and hence remain economically viable (Evenson, 2001; Warren, 2007).

Serving the structural adjustment purpose, the structural policies should particularly aim to encourage generational renewal in family farming. Two typical measures are often undertaken simultaneously: using early retirement to encourage elderly farmers to exit farming, and offering installation aid for young farmers. It is notable that farmland is considered an essential production tool for farming. However, accessing farmland in the initial stage is the most difficult part of the general new entrants. Several studies have revealed that intergenerational transfer within family succession is more likely to foster generational renewal than farm transfers through early retirement scheme in small-scale agriculture (Gibbard, 1997; Kimihi and Nachieli, 2001).

Moreover, a successful intergenerational farm transfer is highly dependent on planning, timing, mutual trust and a shared understanding of the transfer process by the two generations. The other social factors likely associated with retirement and succession decisions of family farmers include the personal preferences for the retiring age of elderly farmers, and the availability of a suitable and willing young successor (Kimhi, 1997). If the elderly farmer decides to retire too early, the farm may be left to an unprepared successor who is not qualified to take over the farm business. Conversely, the retirement decision may come too late to find a successor, since all the young family members may have already engaged in non-agricultural employment or moved to urban areas. National legislation over inheritance also matters. For example, the general inheritance system requires farmland and family assets to be equally passed to all family members. Hence such an equal sharing inheritance has led to a prevalence of small farms and fragmented holdings. Therefore, several countries have introduced financial incentives and reduced taxation to encourage sole inheritor in the family farms, such as Germany and Austria (Gibbard, 1997).

Consequently, the use and provision of specialist advisory and consultancy services for succession planning could be useful to support the process of intergenerational farm transfer because farm succession advisers can help to interpret the related legislation regarding taxation, drafting succession agreements and offering guidance on restructuring of a family-run farm business. In addition to setting up young farmers, another indirect approach for attracting general young people to start up business in the rural areas might be taken into consideration. The causes underlying the scarcity of young farmers would be viewed from the wider perspective of the overall rural economic viability, rather than only focusing on the agricultural sector (Murphy, 2012). It recognizes that the ‘new entry into farming’ problem is likely resulting from the out-migration of rural youth in the countryside. The alternative solution may lie in improving the quality of life in rural areas by enhancing their potential for socio-economic development, and reducing imbalances between rural and urban areas.

Although supporting young people to enter into farming has merited much more importance than assisting rural youth to establish business, due to the scarcity of new farmers, farming-related measures alone will not suffice to deal with the low farmer replacement rate. Therefore, several studies suggest that the possible solution lies in the support that rural youths can obtain regarding opportunities to set up businesses in the rural areas (Irshad, 2013; Osawa, 2014). Greater attention also needs to be paid to the importance of rural economic diversity and the employment status of rural youths. In addition to measures designed to assist new young entrants to become professional farmers, other complementary measures should be created or reinforced in rural areas to encourage general young people to set up businesses in the countryside which provides a more suitable response to emerging needs for rural lifestyle and rural tourism. Under the rural development perspective, however, recent studies indicate that rural economic diversification into non–agricultural activities can also contribute to farming businesses. For example, the DEFRA (2012) proposed a diversifying farming businesses guideline which suggests that farmers can add non-agricultural activities to traditional farming to develop new sources of income by reinforcing the use of the rural resources advantage.

The rural business start-up aids for generating rural livelihoods can therefore be provided as a supplementary measure to support existing schemes for young farmers. The young farmers can use a combination of different measures if they can be qualified by the regulation requirements, such as a business plan and correctly implementing the business plan (Davis et al., 2013). The creation of new economic activity in the form of new businesses or new investments in non-agricultural activities is essential for the development and competitiveness of rural areas. This alternative subsidy would be open to all rural young people and contribute to setting up next generational entrepreneurs in the countryside. Considering the limitation of farming returns in small holdings, diversifying farm business can make better use of agricultural resources and the rural physical environment, by finding new uses for traditional skills and agri-food production, thereby integrating farms into the entire rural economy. The emerging rural tourism industry which is welcomed by rural youths includes tourist accommodation, farm shop, farm café and tea rooms, rural arts and crafts workshops, are good examples for demonstrating the benefits of diversified rural business (DEFRA, 2012). Small-scale farms can also benefit from the development of non-agricultural new economic activities.

CONCLUSIONS

Small-scale agriculture around the world is facing a massive structural crisis, especially the demographic aging problem. Special attention is being paid to family farming agriculture; to become more competitive and sustainable, agricultural structural policy needs to support generational renewal by recruiting professionally trained, progressive and adaptable young farmers. Without generational renewal measures, future farming activities will be at risk, along with negative effects on rural socio-economic development.

Despite the importance of recruiting young farmers, a number of factors threaten the planning and implementation of these schemes. Issues relating to farming economic viability, retirement succession planning, access to markets, land and credit all influence young people's decision on whether or not to enter farming (Tropea, 2014). Given that farm installation requires a considerable financial investment, those young farmers who do not have available access to land, capital, credit and farming skills and knowledge will not be able to establish sustainable farm business. The high costs of farm start-up investment and farm ownership takeover are major barriers for young people to enter into farming (Kazakopoulos and Gidarakou, 2003; Davidova and Thomson, 2014). Therefore, the government needs to organize and provide a more comprehensive policy framework for supporting young farmers, corresponding to different modes of entry into farming channels, and related problems.

Learning from the policy experience of different schemes for young farmers implemented in the EU, several policy implications of setting up young farmers can be inferred from these findings. The main result suggests that inheritance is the most favorable and most feasible way to recruit and set up young farmers, since the majority of small-scale agriculture is operated by family farms. Focusing on the characteristics of family farming structure, the schemes for young farmers should put more effort into the generational renewal mechanism within families. Integrating the public pension payment, early retirement subsidy and young farmer installation aid should exercise effective in promoting intergenerational farm transfer.

Although, providing financial incentives is the common policy instrument to support the installation of young farmers and to encourage elderly farmers to exit their farms. In addition to financial tools (namely grants, preferential loan, interest subsidy, tax reduction, etc.), generational renewal schemes need to be strengthened by introducing other accompanying measures, such as agricultural extension and training programs, and a convenient and affordable land marketing system. More important is that the farm advisory services can play an important role in farm establishment and modernization by offering farm business planning, as well as operation and investment appraisal advice. Furthermore, the succession planning advice can also contribute to smooth the process of intergenerational farm transfer.

Although setting up young farmers is most likely to contribute to improving farming competitiveness, it is acknowledged that the small holdings with limitations of available land, capital and labor are difficult to earn a sufficient livelihood. An alternative policy of the present young farmer-oriented model can be expanded by applying supplementary measures for general rural youths to start up non-agricultural business. From a broader structural perspective, enhancing the rural economic variability can not only lessen the gap between urban and rural economic development, but also indirectly support the livelihood of farm families in rural areas.

Considering that rural youth can hardly find appropriate jobs in the countryside, or make a livelihood in small-scale farming, introducing the rural business start-up aids can stimulate economic activity and employment opportunities in rural areas. Moreover, new entrants to farming also need other rural policy measures to expand their career possibilities in the countryside. Consequently, rural business start-up aids can be regarded as a supplementary measure to support the existing schemes of young farmers. The rural young people will have more options to diversify their rural careers, either to continue with family farming or to establish non-agricultural new business in the countryside.

REFERENCES

Bryant, J. and G. Rossarin. 2005. Rural population ageing and farm structure in Thailand. Rome: FAO.

Caskie, P., J. Davis, D. Campbell and M. Wallace. 2002. An Economic Study of Farmer Early Retirement and New Entrant Schemes for Northern Ireland, Northern Ireland: Queen’s University Belfast.

Davidova, S. and K. Thomson. 2013. Family farming: A Europe and Central Asia perspective. Available from: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Europe/documents/Events_

2013/FF_EUCAP_en.pdf.

Davidova, S., A. Bailey, J. Dwyer, E. Erjavec, M. Gorton, K. Thomson. 2013. Semi-subsistence farming: Value and directions of development. Study prepared for the European Parliament Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/AGRI/studiesdownload.html?la...

Davidova, S., T. Kenneth. 2014. Family farming in Europe: Challenges and prospects, Brussel: European Parliament's Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development.

Davis, J., P. Caskie and M. Wallace. 2013. Promoting structural adjustment in agriculture: The economics of new entrant schemes for farmers. Food Policy 40: 90–96.

De Janvry, A., J. P. Platteau, G. Cordillo and E. Sadoulet. 2001. Access to Land and Land Policy Reforms. In: de Janvry, A., G. Gordillo, J. P. Platteau, E. Sadoulet (eds.), Access to Land, Rural Poverty and Public Action, pp. 1–27. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). 2012. Diversifying farming businesses, UK: DEFRA. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/diversifying-farming-

businesses#further-information.

European Commission. 2012. Rural development in the European union statistical and economic information. Brussels: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, European Commission.

European Communities. 2012. Generational renewal in EU agriculture: Statistical background, Brussels: European Commission, Directorates-General Agriculture and Rural Development.

Evenson, R. E. 2001. Economic impacts of agricultural research and extension. in: Gardner, B. and G. Rausser (eds.). Handbook of Agricultural Economics, pp. 574-616. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Food and Fertilizer Technology Center (FFTC). 2014. Enhanced Entry of Young Generation into Farming Seminars and Workshops, Korea. Available at: http://www.agnet.org/

activities.php?func=view&id=20140314103700.

Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). 2013. Available at: http://www.fao.org/family-

farming-2014/en.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2014. Youth and agriculture: Key challenges and concrete solutions. Rome: FAO.

Gibbard, Roger. 1997. The relationship between European Community agricultural structural policies and their implementation and agricultural succession and inheritance within Member States, Working Papers in Land Management and Development, Berkshire: University of Reading. 06/97. Working Paper. Reading: University of Reading,.

Hazell, P., C. Poulton, S. Wiggins and A. Dorward. 2007. The future of small farms for poverty reduction and growth, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hill, B. and D. Blanford. 2007. Taxation concessions as instruments of agricultural policy. Paper presented at the annual Agricultural Economics Society Conference. England: University of Reading.

Ilbery, B. W., C. Quentin and, T. J. Rickard (eds.). 1997. Agricultural restructuring and sustainability: A geographical perspective. Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CAB International.

Irshad, H. 2013. Attracting and retaining people to rural Alberta: A list of resources and literature review. Canada: Government of Alberta, Rural Development Division.

Kazakopoulos, L. and I. Gidarakou. 2003. Young women farm heads in Greek agriculture: entering farming through policy incentives, Journal of Rural Studies 19:397–410.

Kimhi, A. 1997. Intergenerational Succession in Small Family Businesses: Borrowing Constraints and Optimal Timing of Succession. Small Business Economics 9(4): 309–318.

Kimhi, A. and N. Nachlieli. 2001. Intergenerational Succession on Israeli family farms. Journal of Agricultural Economics 52(2): 42-58.

Matthews, A. 2013. Family Farming and the Role of Policy in the EU. Available at: http://capreform.eu/family-farming-and-the-role-of-policy-in-the-eu/

Murphy, S. 2012. Changing Perspectives: Small-scale farmers, markets and globalisation. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Oizumi, K., H. Kajiwara and N. Aratame. 2006. Facing up to the problem of population aging in developing countries: New perspectives for assistance and cooperation. Tokyo: Institute for International Cooperation Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Osawa, M. 2014. Contemporary discourses on agriculture in Japan: From futureless 3K to sophisticated future lifestyle in LOHAS, living in rural areas, and Hannō Han-x. Bulletin of the Graduate Division of Literature of Waseda University 4: 111–121, Japan: Waseda University.

Quendler, E. 2012. Young farmers with future, Vienna: Bundesanstalt für Agrarwirtschaft.

Regidor, J. G. 2012. EU measures to encourage and support new entrants. Brussels: European Parliament.

Scanlan, H. 2002. Retirement scheme needs fine tuning, Irish Farmers’ Journal 54 (5): 10–18.

Sotte, F. 2003. Young people, agriculture, and entrepreneurship: Key-points for a long-term strategy, The future of young farmers Preparatory meeting for the European Conference, Roma.

Swinnen J. and H. Gow. 1999. Agricultural credit problems and policies during the transition to a market economy in Central and Eastern Europe. Food Policy, 21(1): 21–47.

Tropea, M. F. 2014. CAP 2014-2020 tools to enhance family farming: opportunities and limits. Brussels: European Parliament.

Warren, M. 2007. The digital vicious cycle: Links between social disadvantage and digital exclusion in rural areas. Telecommunications Policy 31(6): 374–388.

|

Submitted as a resource paper for the FFTC-RDA International Seminar on Enhanced Entry of Young Generation into Farming, Oct. 20-24, Jeonju, Korea |

Recruiting Young Farmers to Join Small-Scale Farming: A Structural Policy Perspective

Jiun-Hao Wang

Associate Professor

Department of Bio-industry Communication and Development,

National Taiwan University

No 1, Roosevelt Rd, Sec 4, Taipei 10617, Taiwan

E-mail: wangjh@ntu.edu.tw

ABSTRACT

The small-scale agricultural countries encounter severe structural problems, particularly the rapid ageing of the farmer population and the scarcity of young farmers entering the profession. Determining how to support young farmers is a political priority for the future agricultural policy regarding the small-holding farming world. Given that setting up young farmers has been at the centre of the common agricultural policy in the EU since the 1980s. This article takes the European experience as an example to systematically review current young farmers schemes (YFS). The main objective of this article is to propose a policy framework for recruiting young farmers by systematically reviewing the current supporting measures for young farmers. Result shows that the inheritance from an older family member is the most favorable and most feasible way to recruit young farmers among other entry channels set up farm business. Moreover, the installation aid for young farmers and the early retirement scheme are regarded as coupled instruments on promoting intergenerational farm transfer. However, successfully recruiting young farmers to join small-scale farming is necessary to further employ other supplementary measures, including farm improvement scheme, agricultural extension service, farm succession advice, tax reduction within installation period. Consequently, considering the limitation of farming returns in small holdings, diversifying rural economic activity in the form of supporting non-agricultural new businesses might be an alternative approach for setting up next generational entrepreneurs in the countryside.

Key words: Agricultural structure, Family farm, Generational renewal, Young farmers scheme, Early retirement scheme

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural restructuring is regarded as an important policy issue in the smallholder agriculture countries. The small-scale farming system encounters severe structural problems, particularly the rapid ageing of the farmer population and the scarcity of young farmers entering the profession. The consequences of unsolved structural problems will hamper sustainable agricultural development (Ilbery, Chiotti and Rickard, 1997). For example, the number of young farmers involved in European agriculture is falling fast. With continuously decreasing numbers of European farmers less than 35 years of age, while one-quarter are over 65, effective measures are needed to encourage new entrants into the agricultural sector (European Communities, 2012). The demographic aging problem is more severe in Asian countries than in the EU (Oizumi, Kajiwara and Aratame, 2006).

The age-related structural crisis will lead to an array of agricultural development problems; in particular, farm productivity, market competitiveness, rural economic viability and food security will be under threat. These challenges related to the lack of generational renewal in the farming system should be overcome to secure agricultural sustainability. Therefore, determining how to support young farmers is a political priority for the future agricultural policy regarding the small-holding farming world (Hazell, Poulton, Wiggins and Dorward, 2007).

Unlike market management tools, structural measures have the potential to directly affect farmland consolidation, farm holdings improvement, enlargement of farm size, generational renewal of family farms, young farmer training, early retirement and the adjustment of less developed, less densely populated rural areas, (Gibbard, 1997). However, the policy objectives of maintaining an efficient and prosperous small-scale farm sector are still facing several problems; for example, over-priced farmland results in high entry costs for entering into farming.

Previous studies indicate that, compared to their older counterparts, young farmers have more potential to improve farm competitiveness and achieve better social viability for rural communities. Moreover, young farmers can also promote a wider range of rural socio-economic activities, such as food safety, rural tourism, conservation of traditions and cultural heritage, awareness of the negative effects of farmland abandonment, and participation in local associations (Bryant and Gray, 2005; European Communities, 2012). Therefore, the renewal of farming generations has become an urgent need for the adjustment of the agricultural sector.

Although a growing body of literature has discussed the policy tools required to recruit young farmers into small-scale farming (Quendler, 2012; FAO, 2014), relatively little attention has been paid to the generational renewal of family farming.To fill this knowledge gap, this article takes the European Union (EU) experience as an example to systematically review current young farmers schemes (YFS). The objective of this article is threefold: exploring the structural changes and challenges of small-scale agriculture, discussing the entry obstacles and possible channels for new farmers, and finally proposing a policy framework for recruiting young farmers by systematically reviewing the current supporting measures for young farmers.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The next section briefly introduces the structural changes and challenges of small-scale agriculture. Section 3 discusses the entry obstacles and possible channels for new farmers. This is followed in Section 4 by a systematic review of the existing policy instruments to support young farmers. This article then proposes a conceptual framework for recruiting young farmers under the structural perspective in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes this article with a brief summary and a discussion on policy implications.

CHANGES AND CHALLENGES OF SMALL-SCALE AGRICULTURAL STRUCTURE

The structural changes in land ownership, farm size and age composition of farmers have been understood to have a significant impact on the efficient use of agricultural resources (de Janvry et al., 2001). The agricultural structural policy aims to reallocate resources to those producers with better capability of maximizing farm productivity and profitability. A particular structural challenge concerns the future development of family farms (Davidova et al. 2013; Tropea, 2014). According to the Food and Agricultural Organization’s (FAO) definition, “family farm is an agricultural holding which is managed and operated by a household and where farm labor is largely supplied by that household” (FAO, 2013).

Davidova and Thomson (2013) indicate that family farming is synonymous with small, semi-subsistence farms. Indeed, family farming is the most common business model in small-scale agriculture. On the contrary, large incorporated farms account for only a small proportion of the global farm system. Given that the unique and substantial contribution of family farms to the production of food and public goods, as well as ensuring balanced rural development, the FAO has designated 2014 as the “International Year of the Family Farm” (Tropea, 2014).

The main challenges faced by family farms are illustrated by two features. First, the changing demographic structure of family farm is facing a serious aging challenge. Take the European agricultural sector for example; over 97 percent of Europe’s farms are family-based business. However, only 7 percent of the farmers in the EU-27 are under the age of 35, and nearly 24.5% of farmers are aged 65 or more, see Table 1 (European Communities, 2012). The aging problem of small-scale agriculture is more serious in Asian countries: the percentage of the aged over 65 farmers to the total farm population are 34.3%, 31.8% and 31.2% for Japan, Korea, Taiwan in Taiwan, respectively (FFTC, 2014).

Given that the generational renewal is essential to the sustainability of family farming, the structural policy should put more efforts into “getting old farmers out” in a suitable manner, as well as “recruiting young people into farming” in a way that is competitive and productive in the long-term (Tropea, 2014). Despite its predominance in the agricultural structure, family farming encounters several difficulties in remaining economically viable, such as expensive land cost, low farm efficiency and productivity, high input prices, lacking accessibility of credit or other financial resources, weak bargaining power within the supply chain, fluctuating market prices and being particularly vulnerable to climate change (European Commission, 2012).

The above mentioned challenges can also be identified as the barriers for young people to enter into farming, especially the relatively scarce, as well as expensive land, and the limited access to credit. Therefore, entry to farming through means other than inheritance is difficult in family farming system. It is acknowledged that generational renewal is a major element in the replication of family farming. However, intergenerational transfer is not only about “getting old farmers out” and “establishing new farmers”, but also concerns the transfer of farm proprietary rights and household livelihood security between generations (Tropea, 2014).

Table 1. Changes of age structure in agriculture in the EU

ENTRY OBSTACLES AND POSSIBLE CHANNELS FOR YOUNG FARMERS

The steady decline in the number of family farms has led to a significant shortage of new farmers. Most small-scale agriculture countries are consequently faced with a dual problem: the scarcity of young farmers and the rapid ageing of the farmer population. The severity of the structural situation can be grasped by using the farm holder replacement rate, i.e. the number of holders under 35 divided by the number of holders over 55 (Regidor, 2012; (European Communities, 2012). Therefore, the answer to achieving structural improvement lies in the support offered young people to become more willing to choose the career of farming.

Essentially, agricultural work is regarded as a 3D job (namely dirty, dangerous and difficult) which is in contrast to white-collar work with higher income (Osawa, 2014). Thus it is difficult to recruiting young people to enter into farming. Moreover, three main causes for new entrants to farming decision should be taken into consideration: farm productivity and profitability, volume of employment generated and the ability to earn a satisfactory livelihood (Regidor, 2012); these three factors may become major obstacles to running a small-scale holding.

There are three possible entry channels for young farmers to set up business: (a) family inheritance; (2) taking over from other retiring farmers (related to early retirement scheme); and (3) first installation of farming (for the beginning farmer or new entrant). With the predominance of family farming in small-scale agriculture, the inheritance from an older family member is the most favorable and most feasible way to recruit young farmers among these channels (Sotte, 2003; Quendler, 2012; Regidor, 2012).

Moreover, the early retirement scheme uses a subsidy measure designed to encourage older farmers to retire early, and is awarded when agricultural holdings are transferred to young entrants. Hence, the early retirement scheme is also a useful instrument to accelerate generational renewal outside the family farm. The last channel, from the beginning to entry farming, is particularly difficult for young people to engage in farming career. Accessing affordable land and capital plays a critical role for beginners to establish their farm. Furthermore, the high price and limited land market poses a significant barrier to new entrants and to expanding young farms.

A large body of literature has shown that many young farmers are credit constrained; this demonstrates negative consequences for farm development (Swinnen and Gow, 1999; Davidova et al. 2013). Gaining accessibility to credit is widely acknowledged as a major challenge facing young farmers attempting to establish, enlarge, invest in, or modernize their businesses. Most current schemes targeting young farmers aim to encourage those who are under 40 years of age to choose a farming career, by providing financial support measures. However, different entry channels require specific support mechanisms and requirements; the eligibility for the various YFS measures is conditioned by the entry channel voluntarily or obligatorily adopted by young farmers.

From the agricultural structural perspective, farm inheritance is the optimal channel for the family farming structure. The measures needed to constitute an incentive package for the family successors include young farmer start-up aid and farm holding improvement. In addition, the government should provide succession planning advice to facilitate the successful transfer from one generation to another. In contrast, another entry channel is via older farmer's retirement; the supporting measures should take the transfer process into account, namely the early retirement payment. Lastly, in addition to young farmer start-up aid, for the entry channel for new beginning farmers, the supporting measures should pay more attention to land acquisition and provision of training programs on vocational skills and farming knowledge (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Entry channels for young farmers to set up farm holding.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF SUPPORT MEASURES FOR YOUNG FARMERS: A STRUCTURAL PERSPECTIVE

According to the entry channels to set up farm business, different types of young farmers can be divided into three categories: farm succession within the family through inheritance, farm succession outside the family by taking over from other retiring farmers and new entrants to farming (i.e. the beginning farmer). In general, the land, labor, capital, and farming skills and ability are important input factors for the young farmers to start-up a holding. However, the needs and challenges facing young farmers are diverse, differing by entry channel, farm size and available resources. Hence designing comprehensive and effective policies to support young farmers is problematic.

Support for young people entering into farming has been at the centre of the common agricultural policy (CAP) in the EU since the 1980s. This article will take the CAP experience as an example to illustrate the possible policy instrument for setting up young farmers, and will lead to further discussion. For setting up a new farm holding, the major challenges lie in high costs for farm investments in the initial establishment stage; accessing affordable land and credit is critical to the start-up process (Gibbard, 1997). Therefore, the CAP provides different financial measures for setting up young farmer; they aim at enhancing farm management by renewing the manager generation, encouraging young farmers to invest in farm modernization, and improving the management practices and performances relate to the agricultural holding.

Reviewing the young farmers schemes, which has been implemented in the EU, the existing YFS measures can be classified into three categories, as follows (see Figure 2) (Regidor, 2012; Tropea, 2014):

Figure 2. Policy framework for young farmers scheme and supplementary measures.

In addition to financial subsidy measures, offering tax incentives, creating a convenient and affordable land tenure system, providing farm advice services and training programs, as well as promoting cooperatives and producer organizations are also relevant accompanying policy tools to assist smaller-scale young farmers to start up and promote their farming career (Hill and Blanford, 2007; Tropea, 2014). For example, agricultural training and education courses are important for young farmers to develop their farm businesses. Similarly, the farm advisory services offering business operation and investment appraisal advice would help to ensure progressive productivity through the efforts of young farmers. Both of these agricultural extension programs place considerable emphasis on knowledge transfer and innovation, which allow them to adopt new technologies on their farms and hence remain economically viable (Evenson, 2001; Warren, 2007).

Serving the structural adjustment purpose, the structural policies should particularly aim to encourage generational renewal in family farming. Two typical measures are often undertaken simultaneously: using early retirement to encourage elderly farmers to exit farming, and offering installation aid for young farmers. It is notable that farmland is considered an essential production tool for farming. However, accessing farmland in the initial stage is the most difficult part of the general new entrants. Several studies have revealed that intergenerational transfer within family succession is more likely to foster generational renewal than farm transfers through early retirement scheme in small-scale agriculture (Gibbard, 1997; Kimihi and Nachieli, 2001).

Moreover, a successful intergenerational farm transfer is highly dependent on planning, timing, mutual trust and a shared understanding of the transfer process by the two generations. The other social factors likely associated with retirement and succession decisions of family farmers include the personal preferences for the retiring age of elderly farmers, and the availability of a suitable and willing young successor (Kimhi, 1997). If the elderly farmer decides to retire too early, the farm may be left to an unprepared successor who is not qualified to take over the farm business. Conversely, the retirement decision may come too late to find a successor, since all the young family members may have already engaged in non-agricultural employment or moved to urban areas. National legislation over inheritance also matters. For example, the general inheritance system requires farmland and family assets to be equally passed to all family members. Hence such an equal sharing inheritance has led to a prevalence of small farms and fragmented holdings. Therefore, several countries have introduced financial incentives and reduced taxation to encourage sole inheritor in the family farms, such as Germany and Austria (Gibbard, 1997).

Consequently, the use and provision of specialist advisory and consultancy services for succession planning could be useful to support the process of intergenerational farm transfer because farm succession advisers can help to interpret the related legislation regarding taxation, drafting succession agreements and offering guidance on restructuring of a family-run farm business. In addition to setting up young farmers, another indirect approach for attracting general young people to start up business in the rural areas might be taken into consideration. The causes underlying the scarcity of young farmers would be viewed from the wider perspective of the overall rural economic viability, rather than only focusing on the agricultural sector (Murphy, 2012). It recognizes that the ‘new entry into farming’ problem is likely resulting from the out-migration of rural youth in the countryside. The alternative solution may lie in improving the quality of life in rural areas by enhancing their potential for socio-economic development, and reducing imbalances between rural and urban areas.

Although supporting young people to enter into farming has merited much more importance than assisting rural youth to establish business, due to the scarcity of new farmers, farming-related measures alone will not suffice to deal with the low farmer replacement rate. Therefore, several studies suggest that the possible solution lies in the support that rural youths can obtain regarding opportunities to set up businesses in the rural areas (Irshad, 2013; Osawa, 2014). Greater attention also needs to be paid to the importance of rural economic diversity and the employment status of rural youths. In addition to measures designed to assist new young entrants to become professional farmers, other complementary measures should be created or reinforced in rural areas to encourage general young people to set up businesses in the countryside which provides a more suitable response to emerging needs for rural lifestyle and rural tourism. Under the rural development perspective, however, recent studies indicate that rural economic diversification into non–agricultural activities can also contribute to farming businesses. For example, the DEFRA (2012) proposed a diversifying farming businesses guideline which suggests that farmers can add non-agricultural activities to traditional farming to develop new sources of income by reinforcing the use of the rural resources advantage.

The rural business start-up aids for generating rural livelihoods can therefore be provided as a supplementary measure to support existing schemes for young farmers. The young farmers can use a combination of different measures if they can be qualified by the regulation requirements, such as a business plan and correctly implementing the business plan (Davis et al., 2013). The creation of new economic activity in the form of new businesses or new investments in non-agricultural activities is essential for the development and competitiveness of rural areas. This alternative subsidy would be open to all rural young people and contribute to setting up next generational entrepreneurs in the countryside. Considering the limitation of farming returns in small holdings, diversifying farm business can make better use of agricultural resources and the rural physical environment, by finding new uses for traditional skills and agri-food production, thereby integrating farms into the entire rural economy. The emerging rural tourism industry which is welcomed by rural youths includes tourist accommodation, farm shop, farm café and tea rooms, rural arts and crafts workshops, are good examples for demonstrating the benefits of diversified rural business (DEFRA, 2012). Small-scale farms can also benefit from the development of non-agricultural new economic activities.

CONCLUSIONS

Small-scale agriculture around the world is facing a massive structural crisis, especially the demographic aging problem. Special attention is being paid to family farming agriculture; to become more competitive and sustainable, agricultural structural policy needs to support generational renewal by recruiting professionally trained, progressive and adaptable young farmers. Without generational renewal measures, future farming activities will be at risk, along with negative effects on rural socio-economic development.

Despite the importance of recruiting young farmers, a number of factors threaten the planning and implementation of these schemes. Issues relating to farming economic viability, retirement succession planning, access to markets, land and credit all influence young people's decision on whether or not to enter farming (Tropea, 2014). Given that farm installation requires a considerable financial investment, those young farmers who do not have available access to land, capital, credit and farming skills and knowledge will not be able to establish sustainable farm business. The high costs of farm start-up investment and farm ownership takeover are major barriers for young people to enter into farming (Kazakopoulos and Gidarakou, 2003; Davidova and Thomson, 2014). Therefore, the government needs to organize and provide a more comprehensive policy framework for supporting young farmers, corresponding to different modes of entry into farming channels, and related problems.

Learning from the policy experience of different schemes for young farmers implemented in the EU, several policy implications of setting up young farmers can be inferred from these findings. The main result suggests that inheritance is the most favorable and most feasible way to recruit and set up young farmers, since the majority of small-scale agriculture is operated by family farms. Focusing on the characteristics of family farming structure, the schemes for young farmers should put more effort into the generational renewal mechanism within families. Integrating the public pension payment, early retirement subsidy and young farmer installation aid should exercise effective in promoting intergenerational farm transfer.

Although, providing financial incentives is the common policy instrument to support the installation of young farmers and to encourage elderly farmers to exit their farms. In addition to financial tools (namely grants, preferential loan, interest subsidy, tax reduction, etc.), generational renewal schemes need to be strengthened by introducing other accompanying measures, such as agricultural extension and training programs, and a convenient and affordable land marketing system. More important is that the farm advisory services can play an important role in farm establishment and modernization by offering farm business planning, as well as operation and investment appraisal advice. Furthermore, the succession planning advice can also contribute to smooth the process of intergenerational farm transfer.

Although setting up young farmers is most likely to contribute to improving farming competitiveness, it is acknowledged that the small holdings with limitations of available land, capital and labor are difficult to earn a sufficient livelihood. An alternative policy of the present young farmer-oriented model can be expanded by applying supplementary measures for general rural youths to start up non-agricultural business. From a broader structural perspective, enhancing the rural economic variability can not only lessen the gap between urban and rural economic development, but also indirectly support the livelihood of farm families in rural areas.

Considering that rural youth can hardly find appropriate jobs in the countryside, or make a livelihood in small-scale farming, introducing the rural business start-up aids can stimulate economic activity and employment opportunities in rural areas. Moreover, new entrants to farming also need other rural policy measures to expand their career possibilities in the countryside. Consequently, rural business start-up aids can be regarded as a supplementary measure to support the existing schemes of young farmers. The rural young people will have more options to diversify their rural careers, either to continue with family farming or to establish non-agricultural new business in the countryside.

REFERENCES

Bryant, J. and G. Rossarin. 2005. Rural population ageing and farm structure in Thailand. Rome: FAO.

Caskie, P., J. Davis, D. Campbell and M. Wallace. 2002. An Economic Study of Farmer Early Retirement and New Entrant Schemes for Northern Ireland, Northern Ireland: Queen’s University Belfast.

Davidova, S. and K. Thomson. 2013. Family farming: A Europe and Central Asia perspective. Available from: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Europe/documents/Events_

2013/FF_EUCAP_en.pdf.

Davidova, S., A. Bailey, J. Dwyer, E. Erjavec, M. Gorton, K. Thomson. 2013. Semi-subsistence farming: Value and directions of development. Study prepared for the European Parliament Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/AGRI/studiesdownload.html?la...

Davidova, S., T. Kenneth. 2014. Family farming in Europe: Challenges and prospects, Brussel: European Parliament's Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development.

Davis, J., P. Caskie and M. Wallace. 2013. Promoting structural adjustment in agriculture: The economics of new entrant schemes for farmers. Food Policy 40: 90–96.

De Janvry, A., J. P. Platteau, G. Cordillo and E. Sadoulet. 2001. Access to Land and Land Policy Reforms. In: de Janvry, A., G. Gordillo, J. P. Platteau, E. Sadoulet (eds.), Access to Land, Rural Poverty and Public Action, pp. 1–27. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). 2012. Diversifying farming businesses, UK: DEFRA. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/diversifying-farming-

businesses#further-information.

European Commission. 2012. Rural development in the European union statistical and economic information. Brussels: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, European Commission.

European Communities. 2012. Generational renewal in EU agriculture: Statistical background, Brussels: European Commission, Directorates-General Agriculture and Rural Development.

Evenson, R. E. 2001. Economic impacts of agricultural research and extension. in: Gardner, B. and G. Rausser (eds.). Handbook of Agricultural Economics, pp. 574-616. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Food and Fertilizer Technology Center (FFTC). 2014. Enhanced Entry of Young Generation into Farming Seminars and Workshops, Korea. Available at: http://www.agnet.org/

activities.php?func=view&id=20140314103700.

Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). 2013. Available at: http://www.fao.org/family-

farming-2014/en.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2014. Youth and agriculture: Key challenges and concrete solutions. Rome: FAO.

Gibbard, Roger. 1997. The relationship between European Community agricultural structural policies and their implementation and agricultural succession and inheritance within Member States, Working Papers in Land Management and Development, Berkshire: University of Reading. 06/97. Working Paper. Reading: University of Reading,.

Hazell, P., C. Poulton, S. Wiggins and A. Dorward. 2007. The future of small farms for poverty reduction and growth, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hill, B. and D. Blanford. 2007. Taxation concessions as instruments of agricultural policy. Paper presented at the annual Agricultural Economics Society Conference. England: University of Reading.

Ilbery, B. W., C. Quentin and, T. J. Rickard (eds.). 1997. Agricultural restructuring and sustainability: A geographical perspective. Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CAB International.

Irshad, H. 2013. Attracting and retaining people to rural Alberta: A list of resources and literature review. Canada: Government of Alberta, Rural Development Division.

Kazakopoulos, L. and I. Gidarakou. 2003. Young women farm heads in Greek agriculture: entering farming through policy incentives, Journal of Rural Studies 19:397–410.

Kimhi, A. 1997. Intergenerational Succession in Small Family Businesses: Borrowing Constraints and Optimal Timing of Succession. Small Business Economics 9(4): 309–318.

Kimhi, A. and N. Nachlieli. 2001. Intergenerational Succession on Israeli family farms. Journal of Agricultural Economics 52(2): 42-58.

Matthews, A. 2013. Family Farming and the Role of Policy in the EU. Available at: http://capreform.eu/family-farming-and-the-role-of-policy-in-the-eu/

Murphy, S. 2012. Changing Perspectives: Small-scale farmers, markets and globalisation. London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Oizumi, K., H. Kajiwara and N. Aratame. 2006. Facing up to the problem of population aging in developing countries: New perspectives for assistance and cooperation. Tokyo: Institute for International Cooperation Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Osawa, M. 2014. Contemporary discourses on agriculture in Japan: From futureless 3K to sophisticated future lifestyle in LOHAS, living in rural areas, and Hannō Han-x. Bulletin of the Graduate Division of Literature of Waseda University 4: 111–121, Japan: Waseda University.

Quendler, E. 2012. Young farmers with future, Vienna: Bundesanstalt für Agrarwirtschaft.

Regidor, J. G. 2012. EU measures to encourage and support new entrants. Brussels: European Parliament.

Scanlan, H. 2002. Retirement scheme needs fine tuning, Irish Farmers’ Journal 54 (5): 10–18.

Sotte, F. 2003. Young people, agriculture, and entrepreneurship: Key-points for a long-term strategy, The future of young farmers Preparatory meeting for the European Conference, Roma.

Swinnen J. and H. Gow. 1999. Agricultural credit problems and policies during the transition to a market economy in Central and Eastern Europe. Food Policy, 21(1): 21–47.

Tropea, M. F. 2014. CAP 2014-2020 tools to enhance family farming: opportunities and limits. Brussels: European Parliament.

Warren, M. 2007. The digital vicious cycle: Links between social disadvantage and digital exclusion in rural areas. Telecommunications Policy 31(6): 374–388.